By Joshua Shepherd

Early on the morning of October 3, 1781, a detachment of French hussars trotted down a sandy road in Gloucester County, Virginia. The Frenchmen, newly arrived from Connecticut, were acclimating to the weather. The nights had been cold but daytime temperatures could soar into the 80s. The sun was quickly climbing, and for the cavalrymen, it was sure to be a warm day’s work.

As the hussars rode out into an open field, they spotted a small group of British horsemen. Both groups hastily raised and fired pistols and carbines, shattering the morning stillness. That frantic moment of chance would begin one of the largest cavalry battles of the Revolutionary War.

The swirling cavalry fight that would break out north of Gloucester Point was considered a modest scrape at the time, but would play a crucial role in the most crushing British defeat of America’s War for Independence.

The fateful contest for Virginia in the autumn of 1781 came about as the direct result of increasing strategic incoherence in the British high command. Subsequent to their capture of Charleston, South Carolina, in May of 1780, Crown forces drove deep inland, sweeping aside the remnants of the Southern Continental Army and establishing a strong line of outposts across the Carolina upcountry.

In spite of such early success in the south, the Crown’s effort to subdue the southern countryside had quickly faltered. Over the summer of 1780, Patriot militias struck back with ferocity, annihilating isolated Loyalist units, threatening British supply lines, and ushering in a civil war characterized by old grudges, mutual brutality, and outright revenge.

Lord Charles Cornwallis, the overall British commander in the south, nonetheless enjoyed stunning success against the Southern Continental Army. On August 16, Cornwallis smashed General Horatio Gates’ field army at Camden, South Carolina. The remains of the Patriot army fled beyond British reach, and Cornwallis sought to strengthen his hold on the Carolinas. With no effective Continental army remaining in the field, British victory in the south seemed within reach.

But over the succeeding months, Cornwallis’ plans began to unravel. On January 17, 1781, British arms suffered outright calamity. American General Daniel Morgan, at the head of a flying column of 1,000 men, had been dispatched to western South Carolina to threaten Cornwallis’ left. Keen to neutralize the threat, Cornwallis turned to 27-year-old Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, one of his most trusted officers.

Considered one of the best cavalry commanders in the British Army, Tarleton seemed ideally suited to the task of destroying the Morgan’s small Patriot army. Driving men and mounts mercilessly, Tarleton caught up with Morgan at open meadows known as the Cowpens.

Morgan opted to stand and fight. On the morning of the 17th, Tarleton lashed the American lines, which bent, but did not break. An American counterattack crashed into Tarleton’s battered troops, who fled in confusion. The battle resulted in a near-rout, and Tarleton himself narrowly escaped capture.

Subsequent events during the year would prove pivotal for the British war effort, as well as for Cornwallis. On March 16, Cornwallis caught up with the reorganized southern Continental Army at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina. Both sides were badly mauled in the battle, and Cornwallis, who faced superior numbers, drove the Americans from the field. But it was a ghastly pyrrhic victory that cost him a quarter of his men in the bloody fight.

Exasperated by the stalemated war in the Carolinas and increasingly convinced that occupying the state of Virginia was the key to winning the war in the south, Cornwallis made a decision that would have epic consequences. Rather than remain mired in the strategic morass of the Carolinas, the Earl decided to lead a portion of his men into Virginia—the primary source of men and material for the Patriot war effort in the south. He hoped that a firm subjugation of America’s most populous colony would once and for all break the back of the rebellion.

In fact, the British were already plaguing the Old Dominion. Operating from Hampton Roads, a raiding party commanded by the traitorous Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold had swept up the James River in January of 1781. Largely unopposed, Arnold burned much of Richmond and fell back to Portsmouth.

In the spring, more British troops were funneled into the state. In April, Major General William Phillips led 2,500 Redcoats in another raid up the James River. Phillips brushed aside hastily-raised militia, raided Petersburg, and then pressed on for the state capital. By the time he reached Richmond, however, the strategic landscape had changed.

Overlooking the city were fresh American troops—seasoned Continentals—that constituted a much tougher foe than local militia. A small army of crack troops had arrived in the state under the command of Major General the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette’s small army had been ordered to the state by General George Washington, who was determined to contest the mounting British threat to his home state.

On May 20, Cornwallis’ exhausted troops trudged into Petersburg. After assuming command of British troops already in Virginia and receiving a fresh batch of reinforcements from New York, Cornwallis commanded a respectable army of 7,000 men. With that force, the Earl intended to crush Lafayette and assume firm control of the Old Dominion.

Lafayette, however, had no intention of risking an all-out fight with Cornwallis’ superior forces. He would harry Cornwallis’ army while staying just out of reach. As the British nipped at his heels north of Richmond, Lafayette retreated far to the north, seeking safety in the forested Wilderness south of the Rapidan River. Cornwallis, frustrated that he couldn’t bring the French nobleman to bay, ordered Tarleton to lead his Legion on a lightning raid toward Charlottesville.

Cornwallis was further hamstrung by an unwelcome directive from General Henry Clinton—dispatch 3,000 of his men north to reinforce the garrison of New York City. He was also ordered to occupy a deep water port that could facilitate Royal Navy vessels. His army now weakened, and facing increased opposition from a reinforced Lafayette, Cornwallis opted to occupy the seemingly insignificant port city of Yorktown, Virginia. In ways almost imperceptible at the time, the Royal cause in America had taken a catastrophic turn.

Watching from a distance and closely studying his maps, General Washington saw an opportunity to pounce on Cornwallis’ weakened army. Though he longed to seize New York from the British, the strategic opportunities unfolding in Virginia proved irresistible. “It has been judged expedient to turn our attention towards the South,” Washington wrote.

He combined forces with Comte Jean-Baptiste Rochambeau’s French army and pleaded for assistance from Admiral Francois de Grasse’s French fleet, then operating in the West Indies. Hoping that De Grasse could block any reinforcement of Cornwallis by sea, Washington made plans to trap the Earl by land. Leaving a token force opposing New York, Washington and Rochambeau turned south on August 19 for the 400-mile march to Virginia.

Oblivious to the mounting threats to his army, Cornwallis set about securing his position at Yorktown, situated on the York River, a wide estuary that fed Chesapeake Bay. There the river was only a half mile wide. To control the York, Cornwallis made plans to fortify the opposite bank—a narrow spit of land known as Gloucester Point, or more colloquially as “the Hook.”

As Cornwallis built redoubts and dug earthworks, the combined armies of Washington and Rochambeau arrived at Yorktown on September 28. With the grand Allied army surrounding the town, Cornwallis was completely cut off on the south bank of the river. North of the river, Washington assigned the task of containing British troops on the Hook to Virginia militia under the command of Brigadier General George Weedon.

Weedon had served in the Continental Army’s Third Virginia Regiment, later rising to the rank of Brigadier General. After fighting in most of the battles in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, he resigned and returned home, where he secured command of a brigade of state militia.

Accompanying Weedon was 22-year-old John Mercer, who had also served in the Third Virginia before becoming aide-de-camp to Continental Army General Charles Lee. When Lee ran afoul of General Washington at the Battle of Monmouth and was court-martialed, both he and Mercer resigned in July 1779.

Weedon allowed Mercer to create an additional battalion of militia by picking men who had previously served in the Continental Army, and who’s enlistments there had run out. Mercer then added “the most likely young men who volunteered… and young gentlemen as officers.” After enlisting 200 men, the unit was referred to as the “Grenadier Regiment,” and would be attached to Lauzun’s Legion.

At Gloucester Point, Weedon’s instructions were to contest British foraging parties, but not risk a major action with his militia. Weedon was delighted with his task, as well as American prospects in the coming campaign. By his estimation, Cornwallis had been trapped “handsomely in a pudding bag.”

This wasn’t quite true, as north of the Point, the prosperous farms of Gloucester County offered rich pickings for British foraging parties, who regularly raided for food and fodder.

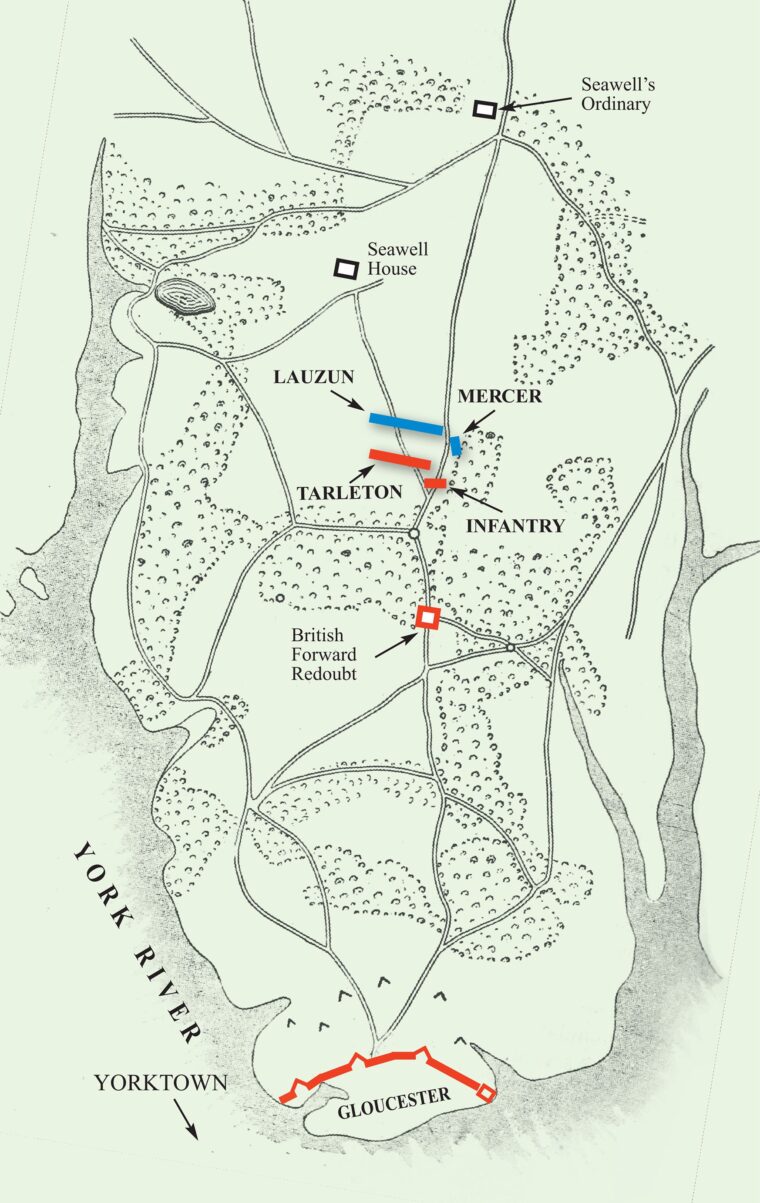

Two small roads led north from the British encampment, affording Crown forces quick access to the interior for foraging operations. To the west, a well-used wagon road flanked the York River and passed by the largest farm in the area, Seawell’s Plantation. Leading directly north from the encampment, the main road out of the Point led directly to Botetourt Town (present day Gloucester Courthouse), about a dozen miles to the north.

Command of the point was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dundas, who ordered a line of works constructed across the narrow confines of Gloucester Point. The four redoubts and intervening artillery batteries were manned by crack outfits, including Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers, elements of the 80th Regiment of Foot, and the riflemen of the Hessian Jaeger Corps.

The Jaegers were under the command of Captain Johann Ewald, a seasoned veteran who looked the part. After a youthful spat resulted in a duel, Ewald had lost his left eye and consequently wore a black eye patch. Having fought in North America since 1776, Ewald was a resourceful commander known for coolness under fire.

His troops were also ideally suited for foraging operations, an unavoidable assignment which Ewald nonetheless found distasteful. The Hessian officer later described one particular operation in which he and his men discovered more than 500 head of cattle. The locals had attempted to hide the livestock from enemy reach, only to lose them all. Ewald understood that the beeves were needed for the army but later confessed that “I felt sorry for the people and wished they had escaped from me.”

Cornwallis’ supply problems worsened on September 5. Admiral Samuel Graves arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay with 19 ships out of New York, but found De Grasse’s fleet already anchored there. The French weighed anchor and angled for Graves’ battle line. After mercilessly pounding each other, the French superiority in numbers began to tell, and Graves drew off.

The two fleets jockeyed for position for five more days, but avoided contact. Finally, on September 10, De Grasse withdrew and re-anchored in the mouth of the Bay. Dispirited by the affair, Graves returned to New York, effectively surrendering the sea lanes to Yorktown to the French. Any hope Cornwallis had of evacuation or resupply by the British Navy had evaporated.

North of Gloucester Point, there was a new Allied commander. Weedon had been superseded by the arrival of French General Claude Gabriel, Marquis de Choisy. Choisy assumed overall command of Allied forces north of the Hook, which included the Virginia militia and 800 French marines, newly-arrived from the West Indies. Among the best under his command was the Lauzun Legion.

The Legion acquired its name from its colorful commander, Armand-Louis de Gontuart, Duc de Lauzun. Not untypical of his class, Lauzun had lived the prodigal youth of an entitled nobleman, and sought glory and redemption under the arms of France. His command, the Lauzun Legion, was a mixed bag of chasseurs, grenadiers, and hussars, bolstered by an artillery detachment. The outfit was a colorful lot recruited from every corner of Europe. Among its ranks were found Germans, Poles, Dutch, Swedes, Russians, and Swiss.

Lauzun’s well-dressed hussars possessed the swaggering élan of an elite corps. The troopers were resplendent in short blue jackets, heavily decorated with elaborate piping. Topped with distinctive hussar shakos, the troopers further set themselves apart by sporting tightly braided hair and rakish mustaches. Despite their gaudy appearance, the French horsemen were formidable opponents. Armed with short carbines, curving sabers, and deadly cavalry lances, the hussars were well drilled and under tight discipline.

Watching these developments from the earthworks at the Point, Captain Ewald gave grudging respect to the makings of the French troops. The Jaeger regarded them as well-disciplined professional soldiers, and, as he thought, “when these soldiers are properly led, everything goes well with them.”

Although Weedon had been ordered not to bring on a full scale battle north of the Hook, Choisy was determined to press the enemy with more resolution. Foraging parties continued to raid north of Gloucester Point, but with French cavalry on the loose, it was becoming a more perilous undertaking.

On the morning of October 3, Dundas headed north from the Hook leading various detachments of the troops under his command. It was expected to be a routine foraging operation. As customary, the troops were keen to nab any foodstuffs of use. The column was composed of infantry, but included a detachment of Tarleton’s cavalry that would serve as security. In tow were a number of wagons necessary for making off with anything of value.

As an additional precaution, Dundas ordered Ewald out with a body of jaegers and Queen’s Rangers who were to take up an advanced position between Seawell’s and Whiting’s Plantations. Ewald was to screen the movements of the foraging party, and set up an ambush for any approaching Allied troops.

After moving inland about three miles, the Britons met with success, locating a field of standing corn that, by early October, possessed full, dry ears that made fine table fare for hungry soldiers. With wary troopers standing guard on horseback, fatigue parties hastily loaded the wagons with corn. By ten o’clock, the wagons were full and Dundas, wasting little time, ordered his column back toward their works on the Hook.

Dundas also rode out to Ewald’s forward position and ordered him to withdraw slowly. The German captain reported that enemy troops were in the area. There had been skirmishes with enemy scouts, but he had been unable to draw them into an ambush. As ordered, Ewald fell back, but noticed that he was dogged by enemy troops every step of the way.

At some point on the return march, Tarleton passed a house near the road, rumored to belong to Mrs. Elizabeth Seawell Whiting, widow of the Commissioner of the Virginia Navy, John Whiting. As the British column marched south, the lady of the house, described as “a very pretty woman,” appeared at the front door to watch the British troops file by. Tarleton, a self-described lady’s man, couldn’t help but stop for a moment and trade a few words. With a good bit of braggadocio intended, no doubt, to impress, Tarleton mentioned that he soon hoped to shake hands with the Duc de Lauzun. To his credit, Tarleton was a commander who routinely led his men directly into combat, and he clearly relished the prospect of crossing sabers with the French nobleman.

With the wagons protected by infantry, some of Tarleton’s dragoons lagged behind to maintain a rear guard. The horsemen chose a likely spot for an ambush, then quietly waited. Within minutes, a handful of mounted Virginia militia, on patrol out of Weedon’s lines, trotted into view. The dragoons waited until the Americans were within range, then unleashed a ragged volley. It seems that all of their shots flew wide.

The gunfire, however, succeeded in scattering the terrified Virginians, who immediately turned their mounts and rode for the rear. There, they encountered a detachment of French hussars with Lauzun at their head. The Virginians breathlessly announced that the British dragoons were out in force, but could report little else. Lauzun, a little disgusted by what he considered the militia’s reluctance to fight, immediately spurred his mount and led his men toward the front.

Crown forces, meanwhile, realized that the French cavalry was operating in the area. Lt. Allen Cameron, leading a group of Legion cavalry bringing up the rear, caught sight of a large dust cloud in the distance, and immediately understood its meaning. He rode up to report the French arrival to Tarleton, who welcomed the news.

True to character, he turned for a fight. Tarleton ordered all of his available mounted troops—which included Legion cavalry, British Light Dragoons, and mounted troops from Simcoe’s outfit—to turn around and form up along a wood line facing an open field. Still unsure precisely where the enemy was, Tarleton accompanied Cameron’s scouting party back out into the field for a personal reconnaissance.

The field was an unused plantation plot, an open meadow known in Virginia as an “old field.” After the soil had been depleted growing tobacco, it had been left fallow. Covered with native grasses and treeless, it was good ground for a cavalry fight.

The French, in fact, were rapidly coming up. Trotting along the road, Lauzun passed by the farmhouse whose matron, still standing by the doorway, struck up a brief conversation with the Duke. Tarleton, she warned, had been there just minutes before, and he was eager to shake hands with the Duke. The Frenchman observed that most Americans considered Tarleton to be invincible in battle, and the housewife was overcome with pity. Lauzun, unperturbed by the exchange, simply quipped that “I had come on purpose to gratify” Tarleton’s desire for a face-to- face meeting.

Lauzun hadn’t ridden 100 yards past the house when he heard the sound of fighting ahead of him. His lead horsemen had abruptly run into Tarleton’s men in the field and both sides had opened fire. Eager to come to grips with the enemy, Lauzun rode forward to take stock of the situation. In the middle of the field, Tarleton and his men were in the open and trading pistol shots with the French. Lauzun could also make out a larger force of British cavalry formed up in the wood line behind Tarleton.

Without hesitation, Lauzun charged into the open. Tarleton, immediately recognizing the splendidly uniformed officer as Lauzun, likewise spurred his horse and charged for the French duke. As their men watched in disbelief, both officers raced in the open between the lines.

Tarleton raised a loaded pistol as he closed the distance. To onlookers, it appeared that a dramatic duel was about to take shape. But in the melee, a stray lance thrown by one of the hussars struck a dragoon horse, and as the Loyalist’s wounded animal careened out of control, it collided with Tarleton’s mount. Both Tarleton and his horse plunged to the ground. In a cloud of dust, Tarleton regained his feet and, remarkably, was unhurt. Lauzun, at full speed, continued charging ahead in hopes of capturing him.

Despite his reputation for personal valor, Tarleton wisely decided for caution. When his men saw his plight, they dashed in front of Tarleton, cutting off the French who were attempting to capture their dismounted colonel. Tarleton made a narrow escape, but was forced to abandon his horse, which Lauzun happily seized as a trophy.

More Loyalists, however, began to pour into the fight. When they witnessed Tarleton’s near-capture, the main body of Legion cavalry, on their own initiative, burst from the wood line and made an impetuous charge on the French Hussars. Their uncoordinated attack fell piecemeal on the French; rather than drive back the Hussars, isolated knots of Legion dragoons drove into the French; a vicious melee ensued.

The staccato popping of pistols and carbines rent the air, and then a fierce metallic rattle reverberated across the field as horsemen clashed sabers. Through a sulfurous haze of powder, mounted men grappled with their enemy nearly face-to-face, shouting with both anger and terror. Mercer’s Virginia Grenadiers, who were coming on the run, began forming up along the northern edge of the field. As the winded Virginians dressed their ranks, they watched the fighting turn against their French allies. Lauzun’s hussars, whose own ranks had gone into action in a disjointed fashion, began to fall back.

Militiaman Robert Forester recalled running down one of the farm lanes of Seawell’s Plantation until his company reached the edge of the wood line. To the Virginians’ front was the open field where Lauzun’s cavalry was in full retreat. The Frenchmen cantered to the rear to reorganize, while the militiamen opened up a fire on the Legion cavalry still milling about the field. Another green militiaman, Gabriel Hughes, was startled by the entire scene. To his inexperienced eyes, the French cavalry had been “badly cut up” by the enemy horsemen.

About 160 Virginians under Mercer’s command succeeded in forming up at the edge of the field. They had plenty to occupy their attention. Loyalist dragoons were to their right front, but a new threat appeared from the left. Tarleton had ordered a party of 40 infantrymen to work their way through a thicket around the Virginians’ left flank.

An exhilarated Mercer watched in admiration as his troops, part of whom stood behind a rail fence, commenced fighting. Mercer later explained that his men didn’t have time to contemplate the coming battle; they had come up on the run, flushed with adrenaline, and commenced firing immediately. Half of the men targeted the enemy dragoons who were about 250 yards away in the field. The other half of Mercer’s men fired at Tarleton’s flanking column of infantry, which had worked its way through a thicket to within 150 yards of the Americans.

Mercer’s battalion fired at the Loyalists and reloaded in good order. Soon, the Virginians began to run low on ammunition; some of the men likely held empty cartridge boxes. Mercer thought that his entire command was down to no more than 100 rounds. Men began to fall as they were struck by enemy gunfire, but despite their precarious position, the militia Grenadiers held firm. Mercer proudly reported that his men exhibited “as much gallantry and composure as any regular corps that I ever saw in action.”

While the Grenadiers kept the enemy at bay, Lauzun rallied his disorganized hussars and prepared for a grand cavalry charge. Lauzun formed up eight troops of his horsemen—about 300 men—into two crisp lines. Hughes watched in admiration at the stirring sight of the French cavalry, which charged out of the woods and thundered back onto the field. As he put it, the hussars gamely “sallied and went at it again.”

Only furious skirmishing, however, would take place. Tarleton’s dragoons had been galled by enemy fire coming from the rail fence, and he had already ordered his men to begin pulling back. From Lauzun’s perspective, it looked as if his hussars “overthrew” the enemy. The two sides sparred, but avoided a major clash. Tarleton and his officers made several attempts to draw the French cavalry into a position where they could be ambushed, but failed to lure the hussars into the trap.

By now aware that the invaluable supplies of corn had made it safely into the lines at Gloucester Point, Tarleton ordered his men to disengage and fall back to safety. His forces warily gave ground, and hussars followed at their heels. Ewald came up in support of Tarleton’s troopers. Accompanying 100 mounted Queen’s Rangers under the command of Captain David Shank, Ewald fought a delaying action, trading scattered gunfire with the enemy and keeping them at bay while Tarleton made good his escape. Without further trouble, Tarleton’s troops withdrew into the British entrenchments.

After watching the retreat unfold, Ewald offered a blunt assessment of the day’s lost opportunities. A shrewd tactician, Ewald lamented that the British Legion had gone into action in a disorganized manner, and that the French took too long to launch a counterattack. “One perceives from this action,” he wrote, “how disorder and delay can spoil the game.”

The fighting had been brief but furious. Mercer reported that in the ranks of his militiamen, 2 men had been killed and 11 wounded. The French hussars had suffered 3 dead and 16 wounded. Tarleton reported that his Legion had suffered an officer and 11 men killed or wounded. During the chaotic rush for Gloucester Point, the French had likewise captured a number of prisoners. Perhaps with a bit of exaggeration, Lauzun claimed that total British losses amounted to over 50 men.

Tarleton regarded the clash at the Hook as little more than a skirmish. But such tactical observations made little difference for the unfortunate souls who were killed and maimed during the fighting. Hughes witnessed the tragic consequences of the battle. He had not been in action before and watched in horror as surgeons frantically scrambled to save the life of one of the stricken French hussars. The man had received a ghastly wound to the neck and was bleeding profusely. The surgeons attempted to sew up the wound but were unable to halt the flow of blood. As Hughes watched in disbelief, the hussar’s life slowly ebbed away.

The result of the Battle of the Hook was far from inconsequential. After receiving further Marine reinforcements from the French fleet later that day, Choisy began tightening the noose around Gloucester Point. The following day he succeeded in stretching a firm line of troops from the York River to Sarah Creek, effectively sealing off Crown forces in their entrenchments. Advanced pickets were thrown out toward the British works, and Choisy strengthened his main line by ordering fatigue parties to fell trees and form a defensive abatis.

Subsequent to the fighting on October 3, Crown forces would not be able to mount foraging operations north of Gloucester Point. Cornwallis’ troops on both sides of the York River were entirely choked off from foraging for desperately needed food and fodder.

On the south bank of the river, the situation dramatically worsened for Cornwallis. On October 6, the Allies commenced digging the first siege trenches; three days later, American and French batteries were positioned to fire on Yorktown. A thunderous bombardment allowed the Allies to inch closer to the town, while Crown forces scraped the earth in a desperate attempt to find cover.

On the evening of October 14, Cornwallis’ position was rendered all but untenable. Attack columns of American and French troops stormed two positions, Redoubts 9 and 10, which were keys to the British defenses. After vicious night fighting at close quarters, the Allies were left in possession of the redoubts, and could complete a second siege trench a mere 300 yards from enemy lines. From such close range, Allied artillery was sure to pound the British army into submission.

To save his army, and perhaps the entire British war effort, Cornwallis latched on to a desperate, last-minute plan. While leaving a skeleton force to man the works at Yorktown, the Earl hoped to make a crossing of the York River with the bulk of his troops. Once the army was over the river, it would attack Choisy’s forces north of Gloucester Point and then make a series of forced marches north. As long as the Redcoats could keep one step ahead of the Americans, Cornwallis’ army could potentially reach the safety of British-held New York.

The operation was planned for the evening of October 16. For the troops manning the works at Gloucester Point, it was an incredibly tense evening. Ewald, deathly sick with a raging fever, was nonetheless on his feet and in command of Redoubts 3 and 4. His troops, who were apprehensive of an attack, stared blindly across the top of the earthworks. The night, recalled Ewald, was “as dark as a sack.” Making matters worse, sickness raged through the ranks. Men by the score were prostrated by fever, leaving the defensive works dangerously undermanned.

At 11 p.m., the first wave of transport boats shoved off from Yorktown. The night sky was beginning to look ominous, but the first batch of troops crossed the river safely by about midnight. As the exhausted Redcoats reached the northern shore, Lt. Col. Robert Abercromby held a brief meeting with the fevered Ewald. Abercromby inquired how many men from the Gloucester garrison could be assembled for a breakout. He blanched at Ewald’s response. The Hessian matter-of-factly announced that Simcoe, most of the Ranger officers, and all the Jaeger officers were dangerously ill. Of the Jaeger rank and file, only a dozen men were well enough to march.

Out on the York River, the situation was worsening. As the second wave of troops was crossing, a tremendous storm swept across the York River, scattering the boats and terrifying the men. A staggering wind blew across the water, and immense thunderclaps rent the sky. Straining at the oars, the men made little headway and were thankful just to stay afloat. After watching the storm for two hours, his anxiety mounting by the minute, Cornwallis called off the whole operation and ordered all of the troops returned to the south bank of the river.

In hindsight, Ewald thought that the entire idea of a breakout to the north was “worthy of admiration” but “the greatest impossibility.” Choisy’s troops were far from pushovers, and even if they could have been brushed aside, two heavily defended ravines were positioned behind the French lines. Moreover, the idea that Cornwallis’ army could have survived swarms of angry Americans across Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey was simply too much to believe.

With no hope of escape, Cornwallis came to grips with his fate. The following morning the Earl dispatched an officer across the lines. Cornwallis was prepared to discuss terms of surrender. After two days of haggling over conditions, Cornwallis relented to Washington’s demands. The garrisons of Yorktown and Gloucester—some 8,000 British, Loyalists, and Germans—were surrendered to the Americans.

Although sporadic fighting would continue for another year, the successful siege of Yorktown constituted the last major operation of the Revolutionary War. Cornwallis’ surrender staggered the courts of Europe, spelled an end to British attempts to subdue the colonies, and ensured the independence of the United States.

The mortifying fate that awaited Cornwallis at Yorktown had come about due to a lengthy string of missteps, faulty decisions, and outright strategic bungling. But the grand course of history often hinges on seemingly minor events. The cavalry skirmish at the Hook, as well as the abortive attempt at a last-minute breakout, had helped seal the fate of the British army at Yorktown.

For his part, Banastre Tarleton thought that the entire debacle at Yorktown had become unavoidable due to the failed breakout from Gloucester Point. “Thus expired the last hope of the British Army,” he said.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments