By David H. Lippman

It was called “rodding,” and it was a complex manual procedure used by British cryptographers at Hut Eight in the Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park to decipher Italian Naval Enigma coded messages. Unlike its more sophisticated German version, the Italian Enigma machine lacked a plugboard that increased the variations on a coded message. Since the Italian Enigma lacked the plugboard, it was easier to solve.

The complicated process of decoding these Enigma messages was developed by a British mathematician named Dillwyn Knox, the very model of the “absent-minded professor.” Knox had a keen eye for talent to staff Bletchley Park, and one of his hires was a London University student in German studies named Mavis Lever, who was only 19 years old when she came to Bletchley Park in 1940.

Knox assigned Lever to use the rodding procedure to definitively break the Italian Naval Enigma. The system worked. What was needed to break a message every day was a good, solid crib—an easily broken and regularly used phrase that was stock to military messages.

Lever went straight to work, using a combination of knowing how military messages followed repetitious formats, her skills as a crossword puzzle fan, and even the idea of cross-ruffing in a bridge game. She found the word “Personale” in a message and realized that signified a “personal” message for some Italian bigshot and was able to find the wheel order and message setting for the signal she was rodding.

With this breakthrough in hand, the British could now read Italian naval message traffic quickly and efficiently, and on March 25, 1941, an Italian Enigma operator transmitted a three-line message that began with an established crib: “Supermarina,” the Italian word for the Naval High Command. Using the rodding procedure, the message was broken and passed on to the Admiralty.

It was a message from Supermarina in Rome to an Italian commander on the island of Rhodes, an Italian holding in the Aegean between Greece and Crete. The message simply said, “With reference to the message 53148 dated 24. Today 25 March is day X-3.”

To the average reader, the message meant nothing. But it would set up one of the greatest victories in the British Royal Navy’s long history, a battle that would severely wound the Italian Navy and take its largest ships out of the war—the Battle of Cape Matapan.

By March 1941, the British situation in the war was as bleak as the seas the Royal Navy was trying to defend. Germany had conquered Europe, and the Luftwaffe’s bombers were pounding London every night. In the Mediterranean, the stunning victory of Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor’s Western Desert Force over a larger Italian force had been quickly reversed by German troops under an unknown German general who would become a legend: Erwin Rommel. The island of Malta was besieged by German and Italian aircraft. Only in Greece, where the Italians had launched a badly planned and organized offensive through Albania, was there hope, as the outnumbered and outgunned Greeks had driven the invaders back.

More importantly, the Royal Navy had lived up to its hundreds of years of tradition of offensive action on November 11, 1940, when a small number of Fleet Air Arm aviators in Fairey Swordfish biplanes from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious had attacked the Italian naval base at Taranto and put out of action three Italian battleships, one of them their newest and largest, the Littorio.

Meanwhile, despite constant Italian and German air raids on Malta, the island’s submarines and torpedo bombers wreaked havoc on Axis convoys supplying Rommel’s tanks. In turn, the Royal Navy was pushing through convoys to keep Malta supplied.

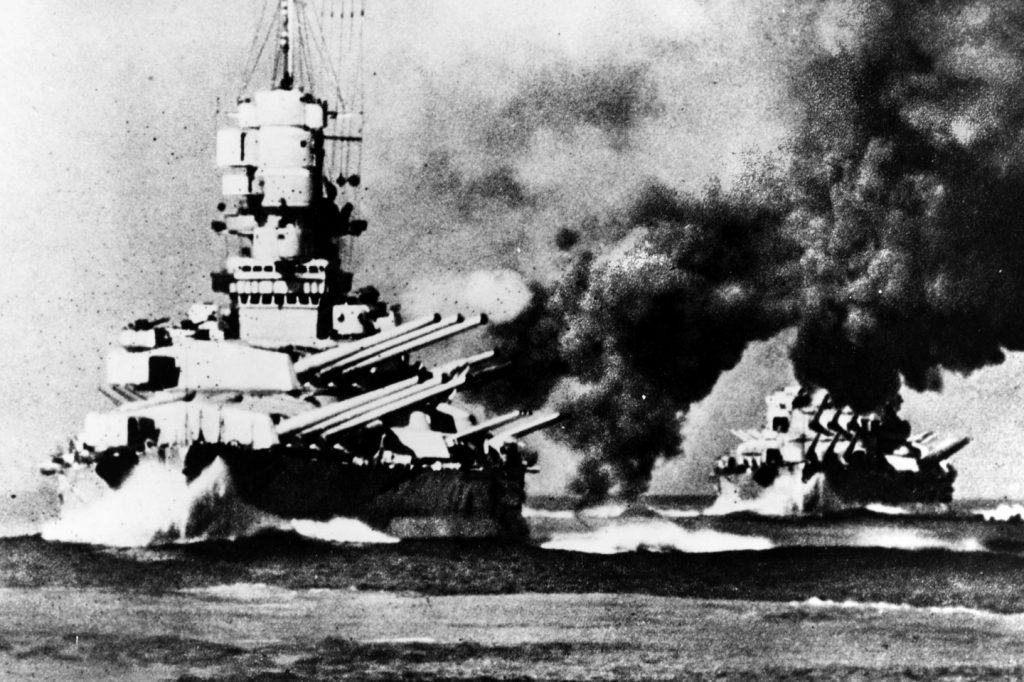

Solving this problem was the responsibility of the Italian Navy, and on paper it was a formidable force. Despite three battleships being dockyard cases after the Taranto raid, it still had three more, headed by the powerful Vittorio Veneto, a speedy ship that packed nine 15-inch guns, sister of the ill-fated Littorio.

In 1940, the Italian Navy, or Regia Marina, was the fifth largest in the world, larger than those of Germany and the Soviet Union. Lacking the worldwide commitments of the Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy, its ships were virtually all deployed in the Mediterranean, a force that consisted of more than 20 cruisers, 61 destroyers, and 70 torpedo boats, divided between the main bases at Taranto and La Spezia. The 100-submarine fleet alone was the world’s largest, divided up between five bases, including Rhodes and Tobruk.

Yet while these numbers were staggering, and the fleet enjoyed the central point in the Mediterranean, it was deficient in nearly every category of naval warfare. Italian ships lacked sonar and radar, even though Italian scientists had created outstanding such devices in the wake of work to develop television programming. Even after the Taranto disaster, Admiral Domenico Cavagnari, the Regia Marina’s chief of staff, balked at deploying radar sets on his ships. He was determined to refight the “Fire-Away Flanagans” of Jutland in the Great War.

The problem was that his gleaming ships lacked the wherewithal. The battleships and cruisers lacked accurate and reliable main guns. Cavagnari accepted one percent tolerances in shell weight and a similar lack of uniformity in propellant charges. The Italians also ignored serious rangefinders, loading systems, firing circuits, and shell fuse defects that had shown up in exercises. While Italian cruisers could crack on 40 knots in a calm sea, their thin armor meant that they disintegrated when hit by shells or took serious damage in heavy weather. Destroyers swamped. Antiaircraft protection was lacking. Training, particularly in damage control, was poor. The Regia Marina did not plan on waging night engagements and so did not train its men or equip its ships for such battles. At night, Italian warships did not assign crewmen to their main turrets, even on combat missions.

Another Italian naval problem was logistics. The fleet lacked ammunition, spares, and most importantly, oil. The Regia Marina started the war with 1.8 million tons, just enough for nine months’ steaming. Operations had to be predicated on consumption limits.

The Italian Navy’s biggest weakness was its inability to see the advantages of a new weapon in warfare: the aircraft carrier. Despite being allowed to build as many as four under the 1942 Washington Naval Treaty, Italy refused to do so. Benito Mussolini saw Italy as an unsinkable aircraft carrier and believed the crack pilots of a nation that had scored amazing aviation feats like Italo Balbo’s flight from Rome to Chicago in 1931 could dominate the Mediterranean.

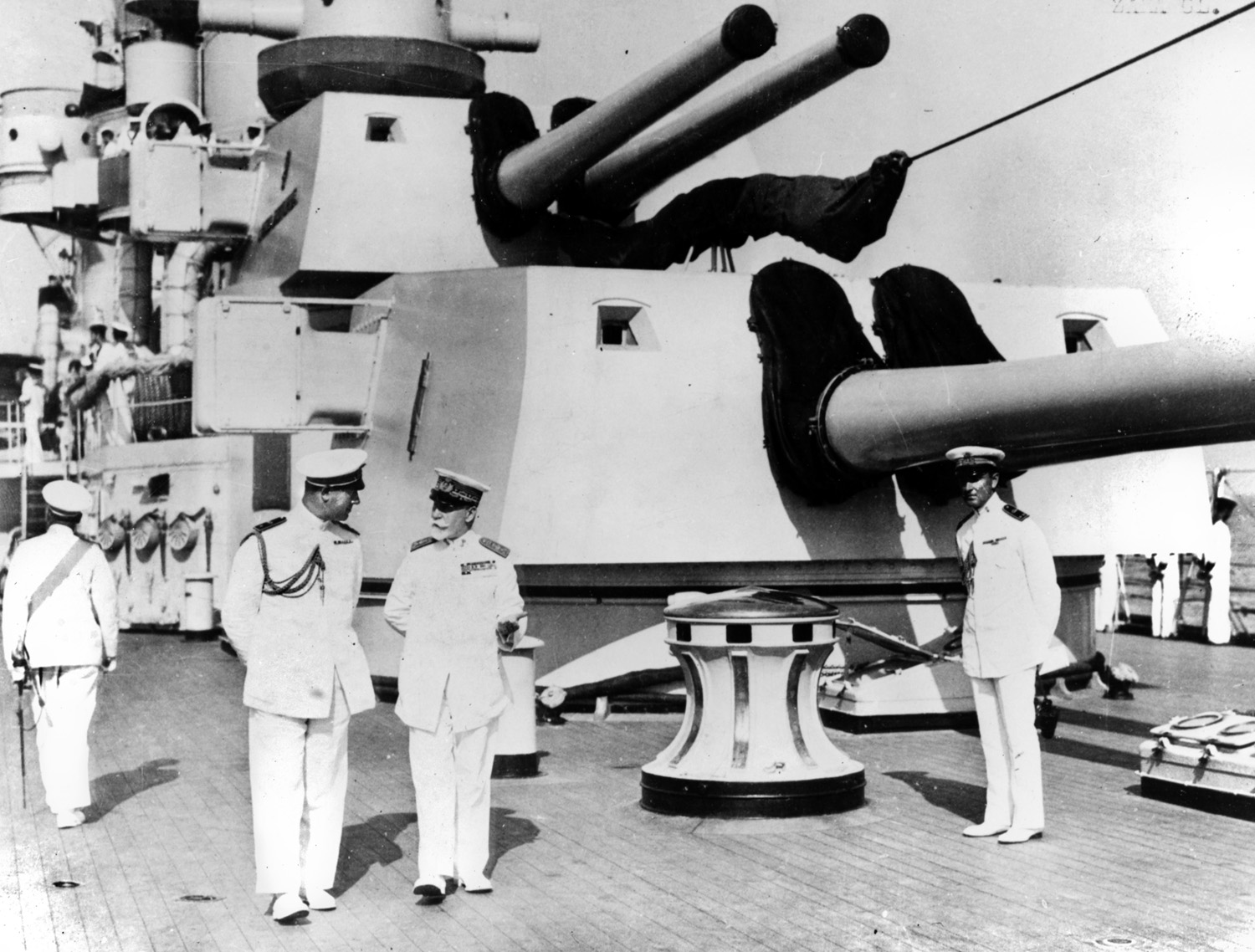

Now, with Rommel on the move, the British Mediterranean Fleet, under Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham (known as “ABC” to his pals) was proving the Royal Navy’s superiority in spirit and technology, if not numbers. HMS Illustrious, the carrier that punched out the Italian Navy at Taranto herself had been knocked out of action in January 1941 by Luftwaffe airstrikes, but her sister ship HMS Formidable had arrived from Britain to replace her, joining a tough force of battleships headed by the flagship, the battleship HMS Warspite.

The supporting cast of battleships bore proud names like Valiant and Barham and was in turn backed up by cruisers like HMS Ajax, and the Australian cruiser HMAS Perth, alongside another Australian warship, the destroyer HMAS Stuart.

All of these ships were better equipped than their Italian counterparts, with more realistic training. Most importantly, they were manned by long-service sailors who had seen long hours of combat steaming, come under enemy attack, and knew their jobs and ships.

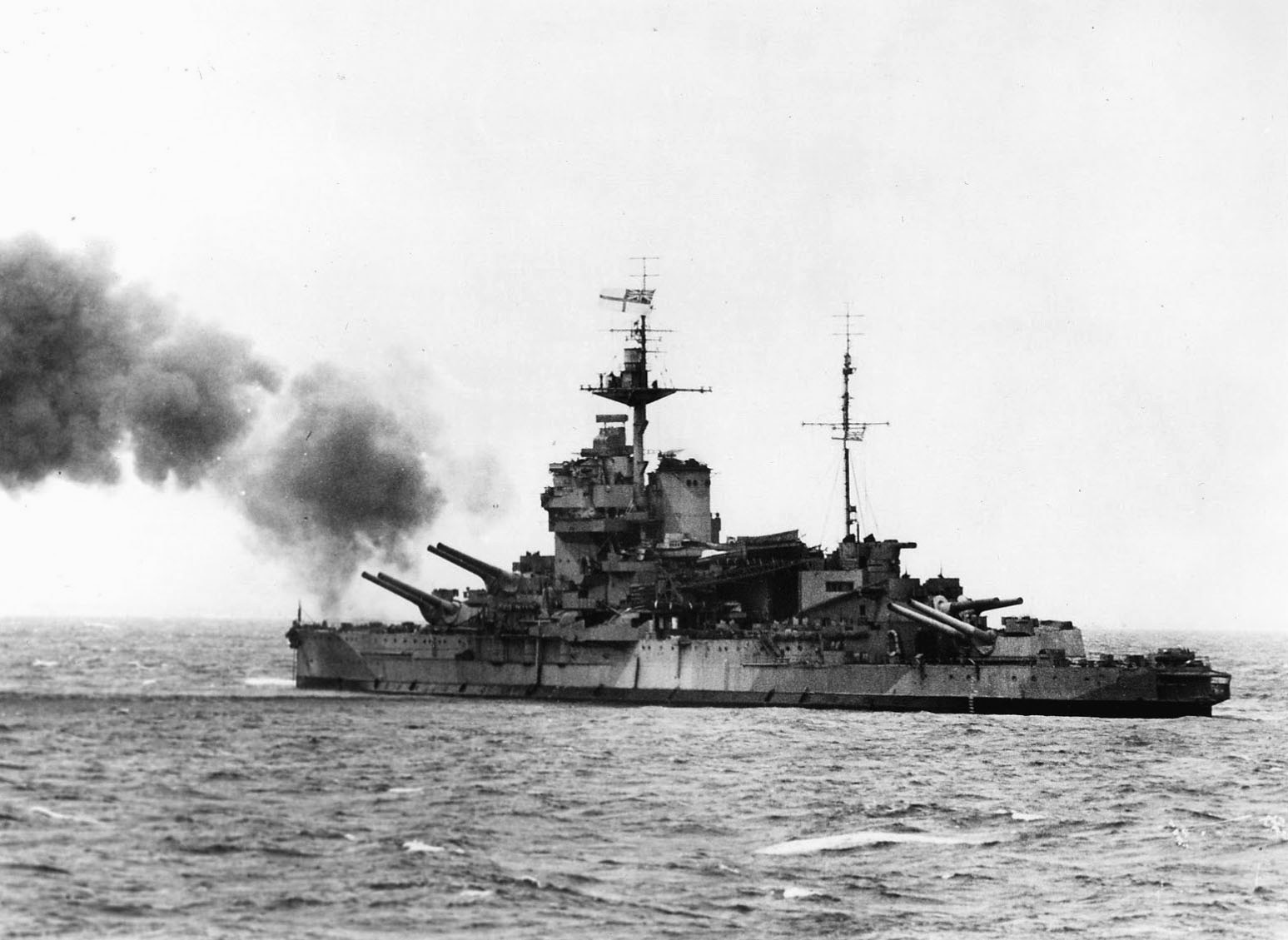

The head of those ships was undoubtedly Warspite, the seventh combatant vessel of that name, a line that began in 1596, which supposedly meant “war’s spite,” a form of contempt for an enemy. This Warspite packed eight 15-inch guns and was only the third oil-powered battleship ordered by the Royal Navy, commissioning in 1915, displacing 30,600 tons. At the heart of a squadron of five sister ships, one of the Royal Navy’s fastest, she had seen action and survived a pounding at Jutland in 1916.

When World War II broke out, Warspite proved such was the case. Under her skipper, Captain Victor A. Crutchley, a World War I Victoria Cross recipient, she steamed boldly into Narvik Fjord on April 13, 1940, and sank six German destroyers and a surfaced U-boat. Off Calabria that July 9, she brushed off the Italian Navy’s battleships handily. When O’Connor’s Australian troops attacked Bardia and Tobruk in January 1941, her guns pulverized Italian fortifications. When the Luftwaffe pounced on Illustrious later that month, a German Stuka’s bomb merely bounced off of one of Warspite’s turrets. At the Royal Navy’s main base at Alexandria, Warspite was the “Cock of the Fleet.”

On March 15, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, boss of the German Navy, summoned Admiral Angelo Iachino, commander in chief of the Italian Navy, to Berlin.

By any navy’s standard, the 51-year-old Iachino was an experienced officer and an excellent gunnery technician. He had a fine reputation and four years of service as naval attaché in London from 1931 to 1934, which gave him considerable knowledge of the Royal Navy.

Now Raeder told Iachino that the two Axis partners were going to launch a double offensive sweep as far as Crete, planned by the Italian Navy’s high command, the Supermarina. The purpose of this naval operation was to smash a British transport of troops from Egypt to Greece, codenamed Operation Lustre.

This series of convoys was transporting the 6th Australian Division, the 2nd New Zealand Division, and a British tank brigade, which would be the main force to face Hitler’s invading troops in Greece. Ambushing them at sea would be a great victory.

To quell Iachino’s concerns about the British Mediterranean Fleet, German intelligence reported that the British had only one battleship, Valiant, in the eastern Mediterranean fully ready for action, and no aircraft carriers. Iachino was sold by this intelligence, even if it was utter rubbish. A great deal of Germany’s wartime intelligence was wrong, whether fooled by the legendary British Double-Cross System of turned German spies or by British deception and camouflage work in battle areas.

The Admiralty warned Cunningham, “Rome informed Rhodes that today 25 March is day minus three. Comment. Signal refers to a message from Rhodes to Rome on 24 March. Any further information will be forwarded when possible.”

The message of the 24th was decoded on the 26th and sent to Cunningham. It told the commander in Rhodes to organize reconnaissance over the route from Alexandria to Crete and Piraeus in Greece, starting March 26. The airport in Crete was to be bombed the night before “Day X” and again at dawn on “Day X.”

Bletchley had not yet seen a message from the Supermarina to Iachino sent on March 25, giving him his sailing orders for the mission they called Operation Gaudo, named for the island just south of Crete where the Italians expected to spot the British convoy.

Iachino was to sweep the area north and south of Crete on March 28, with his ships in three sections, cruisers on the flanks, battleship in the middle, all hunting for the Lustre convoys. “If the enemy is sighted an attack should be made,” but only “if conditions are favorable.” Cunningham did not see that order, either.

But Cunningham was not taking any chances. He signaled his chief of light forces, Vice Admiral Henry Pridham-Whippell, ordering him to be 30 miles south of Gaudo “standing by for eventualities. Your action must depend on circumstances. Your dawn position has been selected to enable you to withdraw in face of an unreasonably superior force or to intercept force as it returns.” Convoy AG9, heading from Alexandria to Piraeus, was to turn back after dusk on March 27. Convoy GA9, in Piraeus, was to stay there.

Iachino headed out to sea from Naples late on the evening of March 26, Vittorio Veneto picking up her cruiser and destroyer escorts. At dawn on the 27th, the battleship steamed through the Straits of Messina, battling choppy seas, into a mist that cut visibility down to 5,000 yards, concealing the Italian advance. Among the young sailors on Vittorio Veneto was a 19-year-old naval cadet named Walter Mazzucato, who had joined her in January. “It made my heart thud seeing such a vast ship for the first time,” he wrote in a memoir. Now he manned one of the immense ship’s 20 37mm antiaircraft guns.

Meanwhile, Bletchley Park tried to assemble the pieces of the Axis puzzle for Cunningham. It was not certain, but it made enough sense to enable Cunningham to summon his 10 senior staff officers for a final strategy session. The staff officers did not know about the Enigma breakthroughs and were not cleared for “Ultra” material. He told them what he thought the Italian Fleet could do the next day—sail to Tripoli or Rhodes or interfere with convoys to Greece. He told the staff to work out which of the alternatives was the most likely possibility. They determined that the Italians must be after the troop convoys. They were the most luscious prize and likely reason for the Italian Navy to expend valuable fuel oil.

They presented this to Cunningham, who readily agreed. “That’s decided then,” and he handed out orders he had already prepared. “I have decided to take 1st Battle Squadron and HMS Formidable to sea after dark tonight Thursday to proceed westward south of Crete,” Cunningham signaled Pridham-Whippell. One minute later, at 12:20 pm on the 27th, a patrolling British Short Sunderland flying boat flown by Pilot Officer Adrian Warburton of 69 Squadron spotted three Italian cruisers and a destroyer 80 miles east of Sicily’s southeastern corner, headed for Crete.

That clinched it. Even so, visibility in the Mediterranean was dropping, and night was coming.

On Vittorio Veneto’s flag bridge, Iachino was disheartened by word that his cruisers had been spotted. Now he believed he had lost the advantage of surprise.

That afternoon, Italian reconnaissance planes swooped over Alexandria to check on the British fleet; the ships were still all in harbor but it was clear now that if surprise was lost the British would recall their convoys. Iachino ordered his varied forces to rendezvous on the morning of the 28th.

Meanwhile, Cunningham launched a brilliant deception exercise to fool the Axis. A keen golfer, Cunningham regularly played at Alexandria’s Sporting Club, and another regular was the Japanese consul, a pear-shaped man who was ridiculed as the “blunt end of the Axis.” But the consul was also a major Axis spy, and when he saw the commander in chief playing golf, it was a fair bet the fleet was not going to sea, and he would report that to his masters and allies.

On the warships, everyone was preparing to sail. Formidable and her escorts steamed at 3:30 pm, and the squadrons of Fairey Albacore and Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers and Fulmar fighters started landing on her flight deck as she sailed off. Orders went to other ships to drop what they were doing and be ready for sea. Among them was HMAS Stuart, which had lost half of her rudder from a near-miss off Benghazi and was awaiting her turn in drydock for repairs. But when Cunningham flag-signaled from Warspite’s foremast, “Raise steam for full speed with all dispatch,” the destroyer’s crew, excited at the opportunity to see action, hurried their repairs and prepared for sea.

At 7 pm the ships headed out. The night voyage proved uneventful, but at 5:55 am, 20 minutes before dawn, Cunningham launched his search planes from Formidable. As the planes flew and the sun rose, everyone on the British ships waited for reports. Forty-five minutes after dawn, the British secured from dawn action stations, and sailors swapped out helmets and antiflash gear for cereal, boiled eggs, and coffee.

For an hour and a half, British aircraft patrolled the seas, until 7:20 am, when one of them spotted four Italian cruisers and four destroyers. Everybody thought the planes had spotted Pridham-Whippell’s ships.

Then Pridham-Whippell, in his flagship, the light cruiser Orion, heading south from Gaudo to rendezvous with the battleships, reported three unknown vessels bearing north from her at a distance of 18 miles, steering eastward.

Cunningham was in the bath when Lee walked in with the news, nervous about how the fiery admiral would react. He could turn into a “caged tiger” when battle neared.

But Cunningham, calm and covered with soap, simply rose from the tub and began dictating orders: “Battlefleet to increase to full speed. Light forces to retire towards us. Formidable to prepare torpedo striking force.”

Iachino was not idle, either. Another deficiency of the Italian Navy was that her battleships and cruisers could launch their reconnaissance seaplanes but not recover them. Nonetheless, Iachino shot off an RO-43 spotter plane at 6 am, and at 6:43 it reported Pridham-Whippell’s cruisers. Iachino had no reports that the British battleships and carrier had gone to sea. Cunningham’s deception had done its job, so Iachino sent his cruisers to draw the British into his waiting heavy guns, theorizing with some accuracy that the Royal Navy would live up to its tradition of aggressive action. He could draw the smaller British ships into the heavy guns of his battleship.

Designated “Force X” on British plot charts, the Italian group consisted of the three heavy cruisers, Trieste, Trento, and Bolzano, along with three destroyers, under Vice Admiral L. Sansonetti. The cruisers’ 8-inch guns out ranged the four British light cruisers’ 6-inch weapons. Worse, Pridham-Whippell did not know that another Italian group under Vice Admiral C. Cattaneo, comprising three more heavy cruisers, Zara, Pola, and Fiume, two light cruisers, and six destroyers, was nearby. Nonetheless, Pridham-Whippell was not prepared to flee. His four cruisers—Orion, Ajax, Perth, and Gloucester—and four destroyers hoisted five battle ensigns each as the Italians opened fire at 8:12 am.

The Italians’ first shots were short, but they closed the range with superior speed, concentrating fire on Gloucester, closing to 23,500 yards. At that point, Gloucester opened fire with three salvos. All fell short, but the Italians turned away for a few minutes, then onto a parallel course. As they did, the British destroyer Vendetta developed engine trouble, and Pridham-Whippell ordered her to Alexandria.

At 8:55, the Italian cruisers checked fire, turned in a circle to port, and headed northwestward, having claimed two hits.

Pridham-Whippell chose to shadow the ships that had engaged him, racing northwestward, unknowingly straight for Vittorio Veneto and her 15-inch guns. The Italian dreadnought had gone to action stations, and 19-year-old cadet Mazzucato was now at his post.

Meanwhile, Cunningham cranked his three battleships up to 22 knots, the fastest the Barham could do. She had not been modernized like Valiant and Warspite between the wars. Cunningham ordered Valiant to connect with Pridham-Whippell as soon as possible and Formidable to launch an airstrike on the enemy fleet.

On Vittorio Veneto’s flag bridge, Iachino wondered why Pridham-Whippell had apparently withdrawn from Samsonetti’s cruisers. The Italian ships had higher speed than the British ships, so they were guaranteed to catch up and act as picadors for his battleship, which would play the role of matador.

At 9 am, Iachino was given a message from Rhodes: “At 0:745 No. 1 aircraft of the Aegean strategic reconnaissance sighted 1 carrier 2 battleships 9 cruisers 14 destroyers in sector 3836/0 course 165° 20 knots.” Iachino promptly drew the wrong conclusion: the Italian reconnaissance plane had sighted his own force and reported it as British. He estimated that the British cruisers were southeast of him and ordered his ships to head east and jump at them from the north and on their starboard quarter. Meanwhile, Samsonetti would double back on the British cruisers and drive them straight to Vittorio Veneto. The British would be caught in a deadly sandwich of heavy gunfire.

On Formidable, the carrier prepared to launch a strike of six Albacore biplanes from No. 826 Squadron under Lt. Cmdr. Gerald Saunt, covered by two Fulmar fighters of No. 803 Squadron, to support Pridham-Whippell. But when the Italian cruisers broke off the action, Cunningham delayed the strike to avoid revealing the presence of this potentially decisive weapon. Instead, Cunningham requested RAF 201 Group to send in Sunderland flying boats to shadow the Italian fleet.

At 9:39, Cunningham ordered Formidable to launch the strike it had readied to hit Force X, warning Pridham-Whippell that the Albacores were on their way. Pridham-Whippell misread the message to think that an Italian or German airstrike was headed for him because when No. 826 Squadron arrived the British ships greeted them with antiaircraft fire. Fortunately, nobody was hurt.

On Orion, British gun crews sat atop their turrets at 10:58 am to avoid the intense heat inside them, and stewards and cooks provided everyone with action bully beef sandwiches. On the bridge, Orion’s executive officer, Commander T.C. Wynne, nudged operations officer R.L. Fisher and said, ‘What battleship is that over on the starboard beam. I thought ours were miles east of us?’”

As Fisher whipped out his binoculars to look at the hull to the north, a 15-inch salvo splashed into the water near Orion. Vittorio Veneto had announced her presence with authority.

Pridham-Whippell reacted immediately, ordering his cruisers by radio to make smoke, turn together to 180 degrees, and go to top speed.

On Warspite, Cunningham and his staff heard these urgent messages and wondered what Pridham-Whippell was up to. Cunningham read the signals and said, “Don’t be so damn silly. He’s sighted the enemy battle fleet, and if you’d done any reasonable time in destroyers, you’d know it without waiting for the amplifying report. Put the enemy battle fleet in at visibility distance to the northward of him.”

Now Sansonetti’s cruisers sprinted into action from Pridham-Whippell’s starboard quarter, putting the British cruisers in the position Iachino wanted. The Italian battleship’s fire was accurate but with too large a spread. A near-miss sent splinters scratching Orion. Only the smoke kept the Italian ships—lacking radar—from scoring major hits. Gloucester, her top speed reported at 24 knots due to engine trouble the night before, somehow cranked up to 30 knots. Unfortunately for her, Vittorio Veneto could do 31.

At 11:27, the British cruisers’ situation seemed hopeless. At that same time, Formidable’s striking force arrived. Among the Albacore pilots was Lieutenant Frank Hopkins, who rose to the rank of admiral and later gained a knighthood.

“We sighted on large warship, escorted by four destroyers, steaming towards our cruisers, and shortly after this the large warship, which turned out to be a battleship of the Littorio class, opened fire on our cruisers. Since the battleship was steaming at 30 knots, it was clear that our cruisers were in for trouble, and they could expect no help from the main fleet, which was more than 80 miles away,” he wrote later.

After the escorting Fulmars shot down a German Junkers Ju-88 fighter that had been sent to the scene, the Albacores moved in.

“Unless we could do something quickly our cruisers would be picked off one by one at long range by the Vittorio Veneto. The trouble was that we were all abaft the beam of Vittorio Veneto. She was steaming at 30 knots, the wind at our height was 30 knots against us, so that since our air speed was only 90 knots we were catching up at a relative speed of only 30 knots. I think it took the best part of 20 minutes to creep up to a suitable attacking position ahead of Vittorio Veneto. Throughout most of this time she and her four destroyers kept up a spirited but fortunately inaccurate bombardment with their A/A guns. The battleship was also doing some good shooting at our cruisers and appeared to be straddling them frequently. I suspect that the only reason that they did not score any direct hits was that the spread of their individual salvoes was too large,” Hopkins wrote.

Despite Saunt’s determined attack, all torpedoes missed Vittorio Veneto, but they saved the British cruisers. Iachino broke off the action, realizing that if a British carrier was nearby, so were British battleships. He ordered his ships to head on course 300° at 28 knots, heading home. Pridham-Whippell, heading south and behind a smoke screen, could not see the Italian ships retreating.

When the smoke cleared, Pridham-Whippell saw only a clear horizon to the north instead of Vittorio Veneto and to the northwest, where Italian cruisers had been bearing down on him. His ships were safe. He ordered them to connect with Cunningham, who was now 45 miles east-southeast of Iachino, chasing the Italians at top speed, but he could not catch up with the faster enemy unless they could be slowed down by Formidable’s aircraft.

To do so, Formidable was detached with two destroyers to enable her to crank up to her higher speeds, both to launch and recover aircraft and to close the distance with the Italians.

Formidable launched a second strike from No. 829 Squadron, consisting of three Albacores and two Swordfish, under Lt. Cmdr. J. Dalyell-Stead, with two Fulmar fighters to escort them.

Meanwhile, British battleships and aircraft pursued the withdrawing Iachino. Pridham-Whippell’s cruisers and destroyers hooked up with Cunningham at 12:28 pm, and Cunningham briskly signaled his junior: “Where is the enemy?”

Pridham-Whippell had no alternative but to respond: “Sorry, don’t know; haven’t seen them for some time.”

Those Italian warships sprinted along at 28 knots until 2 pm, when Iachino cut speed to a slightly more sedate 25 knots to conserve fuel in his destroyers. That still outran Cunningham, but closed the range for Formidable’s strike.

On his armored flag bridge, Iachino finally got his first accurate intelligence information at 2:25 pm. The first was a delayed signal from Rhodes reporting a British force of one battleship, one carrier, six cruisers, and five destroyers some 80 miles east of him. The second, from the Supermarina, based on radio direction-finding cross-bearings, reported enemy ships 170 miles to the southeast. From his experience, Iachino believed that aircraft reports were unreliable, particularly on reported positions. Either way, the British were at sea with a carrier, and while Iachino was not too concerned about the Royal Navy’s slower moving battleships, their carrier worried him. He had sufficient speed and hitting power to defeat any surface opponent, but not the Fleet Air Arm’s maneuverable torpedo bombers.

The Fleet Air Arm was keeping Iachino busy. At noon, Swordfish from the Fleet Air Arm base in Maleme in Crete attacked his cruisers. At 2:20 pm, the RAF joined in with three Bristol Blenheim bombers from Greece. At 2:50, 3:30, and 7 pm, more Blenheim bombers tried their luck, but none gained hits. Iachino was angry at the constant pinpricks and even angrier that neither the Italian nor German air forces sent him fighter cover.

At 3:10 pm, Formidable’s strike, headed by Dalyell-Stead, arrived over the Italian fleet, emerging from out of the sun, and the three Albacores, 5F, 5G, and 5H, swung ahead of Vittorio Veneto. Iachino ordered his dreadnought 180° to starboard. The two Swordfish, 5K and 4B, attacked Vittorio Veneto from her starboard side.

“We had all our hearts and minds fixed on the aircraft,” Iachino wrote later, adding that he was impressed by their skill and courage. The leading aircraft launched its torpedo just 1,000 yards ahead of the battleship, then turned to his left, coming under intense antiaircraft fire. The Albacore staggered, dipped violently across the track 12 yards ahead of Vittorio’s bows, and plunged into the sea 1,000 yards on the starboard hand.

Mazzucato had a grandstand seat for the action at his 37mm antiaircraft gun. “The aircraft that was almost aligned with the bow of the ship attacked with extreme resolution and a spirit of self-sacrifice in the face of a hail of antiaircraft fire. Hit by it, the plane fell into the sea and disappeared,” he wrote later.

The pilot who died was Dalyell-Stead himself, who received a posthumous Distinguished Service Order. Also killed were his observer, Lieutenant Cooke, who received a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross, and Petty Officer Blenkhorn, the telegraphist/air gunner, who received a posthumous Distinguished Service Medal.

Incredibly, they were the only British casualties in the entire battle.

As Vittorio Veneto swung to starboard, Dallyell-Stead’s torpedo hit home, just above the outer port screw 15 feet below the waterline, shaking the immense dreadnought. More than 4,000 tons of water flooded into the battleship, smoke rings flew out of her funnel, and she settled by the stern.

Vittorio Veneto was stopped, and along with her the entire Italian Fleet. Cunningham’s battleships were just 65 miles astern, unknown to Iachino, and closing at 22 knots.

The British planes formed up to head back to Formidable and reported at least three hits and that Vittorio Veneto and her escorts had “made a large decrease in speed.” Rear Admiral Denis Boyd on Formidable passed that news on to Cunningham, who answered, “Well done. Give him another nudge at dusk.”

Cunningham ordered Pridham-Whippell to take his cruisers ahead of the battleships at their higher speed and locate Iachino’s ships, now that they had been slowed down. Cunningham had two hours of daylight left and hoped to achieve a decisive engagement by nightfall.

On Vittorio Veneto, damage control parties coped with a list to port and stern and stopped engines. Within a short time, the battleship’s engines were working up to 16 knots on one propeller. With his battleship damaged, Operation Gaudo had to be aborted. Safety was 420 miles away at Taranto to the northwest.

Studying his charts, Iachino determined that an advancing British battleship could only do 20 knots and it could not catch him by nightfall. The real danger would be an air attack by day, followed by a destroyer attack by night. That would require a close screen of escorts to prevent the destroyers from breaking through the barrier. As he watched the cruisers Zara, Pola, and Fiume take up their stations on his starboard side, Iachino studied them with pride. He had served on board all three, knew their captains, and commanded all three as head of the 1st Cruiser Division. He was seeing them by day for the last time.

On Formidable, six Albacores of No. 826 Squadron and two Swordfish of No. 829 Squadron were spotted on the flight deck for the “nudge” Cunningham sought, and they flew off at 5:35, again under Saunt. After making the attack, they were to land at Maleme rather than risk a difficult night recovery on Formidable. They were supported by two Swordfish of No. 815 Squadron from Maleme. They met up at five minutes before sunset.

Meanwhile, Cunningham’s big ships steamed on. The admiral flashed his intentions to the ships by signal blinker. “If cruisers gain touch with damaged battleship, 2nd and 14th Destroyer Flotillas will be sent to attack. If she is not then destroyed, battlefleet will follow in. If not located by cruisers I intend to work around to the north and then west and regain touch in the morning.”

The burden was being put on the long-serving destroyermen, their tried tactics, and reliable torpedoes. The 10th Destroyer Flotilla, under Captain H.M.L. Walker, consisted of HMAS Stuart, HMS Griffin, Greyhound, and Havock. They would take station ahead of the battlefleet and act as a screen. The14th Flotilla, under Captain Phillip Mack on Janus, consisting of Nubian and Mohawk, would position itself one mile on the port bow of the battleships. Finally, 2nd Flotilla, under Captain H.S.L. Nicholson on Ibex, with Hasty, Hereward, and Hotspur, would take up station one mile on the starboard bow. As soon as Pridham-Whippell made contact with Vittorio Veneto, 2nd and 14th Flotillas would unleash their torpedoes on the Italian battleship.

Cunningham launched Warspite’s Swordfish seaplane to find and fix the Italian ships at 5:45 pm. Realizing he would have to make a night sea landing, Lt. Cmdr. A.S. Bolt, the pilot, took extra flame floats with him. He spotted the Italian battleship at 6:20 pm and reported the sighting 11 minutes later. The Italians were heading west-northwest at 15 knots, 43 miles from the British. Studying their plot chart, the British realized they had a 7-10 knot speed advantage over the Italians.

Cunningham had to cut the distance from 50 miles to 12 to bring his 15-inch guns within range of the enemy. That would take four hours. So it was up to the destroyers, sprinting ahead at 36 knots, to tie into the Italian ships.

Now Bolt reported the composition of the Italian fleet: Vittorio Veneto at the center of a column with four destroyers, two fore and aft, with two more columns port and starboard. The port outer column consisted of three destroyers and the starboard outer column of four destroyers. The port inner column was made up of the heavy cruisers Trento, Trieste, and Bolzano. The starboard column consisted of the heavy cruisers Zara, Pola, and Fiume. The battleship was therefore well shielded from night attack. Iachino’s neat and well-organized column needed to be broken up.

Sun was setting at about 7:15 pm when Pridham-Whippell’s radar picked out the Italian warships. At that time, Formidable’s planes droned in. Iachino saw them, too, swooping out of the orange western sky like vultures. “These were the planes,” Iachino wrote later, “whose job it was to give us the coup de grace at nightfall.”

The Albacores swooped in from a darkening sky as the Italian ships opened fire with all their guns and illuminated the scene with their searchlights. Iachino ordered his ships to turn 30° to starboard.

The British planes plunged in to attack despite the heavy fire and launched their torpedoes, aiming for Vittorio Veneto, but missing. The very last plane, aircraft 5A, piloted by Sub-Lieutenant C.P.C. Williams, attacked at 7:45 pm and pressed in on close range despite heavy Italian fire and blinding searchlights. He slammed a torpedo not into the battleship, but the escorting Pola, blasting open her starboard side and flooding her engine and No. 3 boiler room. Pola’s electrical power failed, three more compartments flooded, and the main engines stopped. The cruiser was in no immediate danger of sinking but could not move.

Incredibly, Iachino’s four columns continued to steam on. He did not know that Pola was sitting helpless in the dark until 8:15 pm, half an hour after she was hit.

“Now came the difficult moment of deciding what to do. I was fairly well convinced that having got so far it would be foolish not to make every effort to complete Vittorio Veneto’s destruction,” Cunningham wrote in his memoirs. “At the same time it appeared to us that the Italian admiral must have been fully aware of our position. He had numerous cruisers and destroyers in company, and any British admiral in his position would not have hesitated to use every destroyer he had, backed up by all his cruisers fitted with torpedo tubes, for attacks upon the pursuing fleet.”

Cunningham was taking a great risk—the Royal Navy had not fought a night engagement since the Battle of the Nile in 1798, and even then Nelson had attacked before dark.

Another admiral was furious at that moment. A 8:18 pm, Iachino finally got word that Pola was hit and stopped. He ordered Cattaneo to head back with Zara, Fiume, and four destroyers to protect the cripple and bring her home. Cattaneo asked to send two destroyers—thus reducing the risk to his own heavier ships—but Iachino wanted the heavier ships on hand if the British attacked and an admiral on the scene to assess and coordinate the response and defense.

Cunningham ordered the destroyers he had sent forward to attack. At 8:37, his radiomen sent the signal: “Immediate. 14th DF, 2nd DF, from Commander in Chief: Destroyer flotillas attack enemy battlefleet with torpedoes. Estimated bearing and distance of center of enemy battlefleet from Admiral 286° 33 miles at 8:30. Enemy course and speed 295° 13 knots.”

Pridham-Whippell had already cranked his ships’ speeds up to 30 knots and into a search formation seven miles wide. At about 7:40 pm, he was only 12 miles from the Italian fleet, and his lookouts saw the flashes of antiaircraft fire and searchlights in the distance from Formidable’s airstrike.

By 8:30, Orion was nearing the target, and Pridham-Whippell informed Cunningham that it might be the damaged Vittorio Veneto. An immobile battleship was a prize beyond belief. Cunningham promptly ordered his ships to form a battle line with Warspite leading, followed by Valiant, Formidable, and Barham, each 600 yards apart. It seemed incredible that the daring Cunningham would put an aircraft carrier in a battle line, but he did so. The destroyers Stuart and Havock were a mile to starboard, Greyhound and Griffin one mile to port.

As Warspite lacked radar, it was Valiant’s job to locate the contact. She found the immobile ship six miles distant on her port bow, at a length of about 600 feet.

Cunningham ordered his battle line to change course toward the radar target and the port side destroyers to head for the starboard side to clear the line of fire. On Valiant, everybody in the radar room watched the green pulsing radar lines on the cathode ray tube come together. A young midshipman who answered to the title of Prince Philip of Greece stood at his action station on the port side searchlight on the bridge, awaiting orders to snap his beam on the bearing given by the radar operator.

The immobile ship was Pola, of course, and the two mysterious arrivals were Zara and Fiume, there to save their sister. And if the British were surprised, the Italians were even more so. Their crews had been stood down from battle stations and were prepared to assist Pola. Fiume had her towing cables out and ready. At 10:25, Cattaneo fired off a red signal rocket to let Pola know he had arrived. In the burst of the rocket, Cattaneo’s lookouts reported a second force ahead of them and to port—Cunningham’s battle line.

Cunningham used his tactical radio to order his big ships to change course to starboard, keeping them in line ahead. Unlike the Italians, they knew the enemy was there and everyone was at action stations. Formidable pulled out to starboard, useless in this kind of action, so as not to risk her precious flight deck.

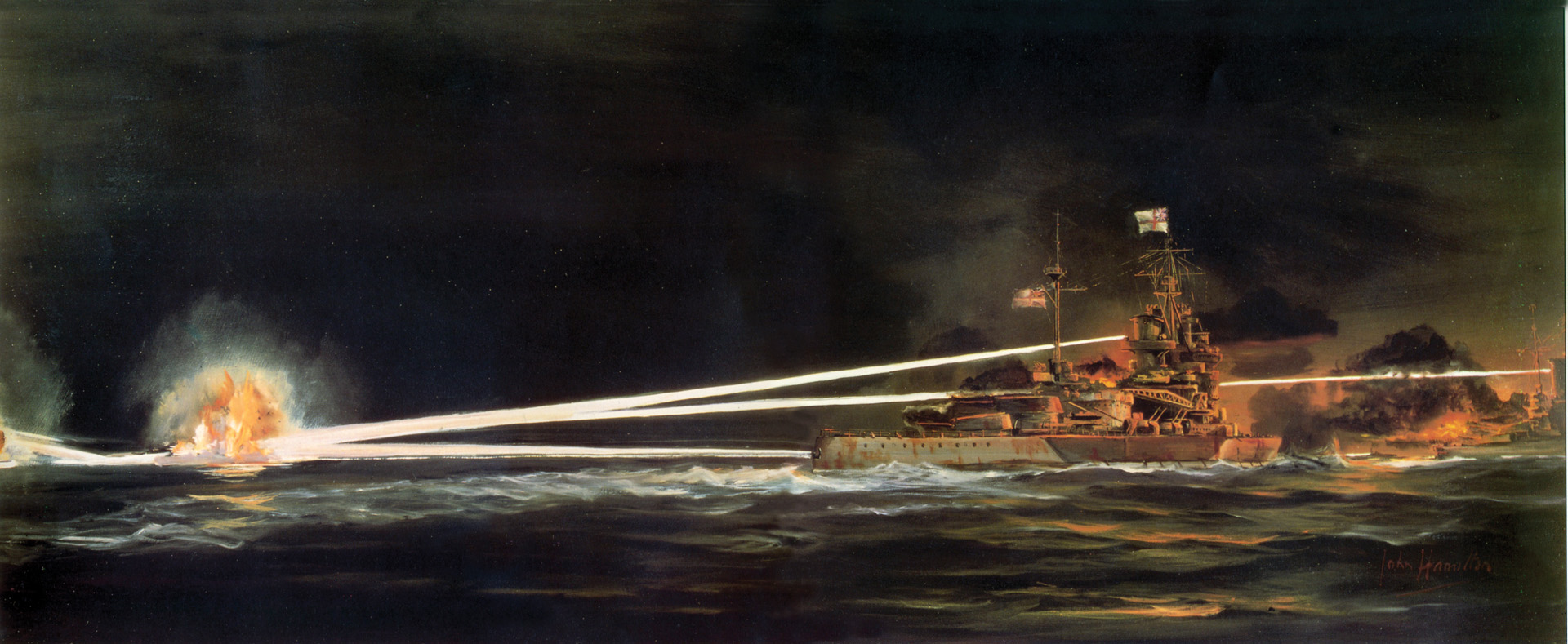

“I shall never forget the next few minutes,” Cunningham wrote. “In the dead silence, a silence that could be almost felt, one heard only the voice of the gun control personnel putting the guns on to the new target. One heard the orders repeated in the director tower behind and above the bridge. Looking forward, one saw the turrets swing and steady when the 15-inch guns pointed at the enemy cruisers. Never in the whole of my life have I experienced a more thrilling moment than when I heard a calm voice from the director tower—‘Director layer sees the target;’ sure sign that the guns were ready and that his finger was itching on the trigger. The enemy was at a range of no more than 3,800 yards—point-blank.”

At that moment, Zara’s Captain L. Corsi said to Sub-Lieutenant Giorgi Parodi: “There’s the Pola. Is that our recognition signal?”

Almost as if in answer, Greyhound snapped on a searchlight that illuminated the third Italian ship in line, Fiume, showing a silvery blue shape. The beam revealed Zara second in line in silhouette and the destroyer Alfieri on the far left, first in line. On Valiant, Prince Philip was ordered to “Open Shutter” and lit up his searchlight. It illuminated half of a cruiser. It was 10:27 pm.

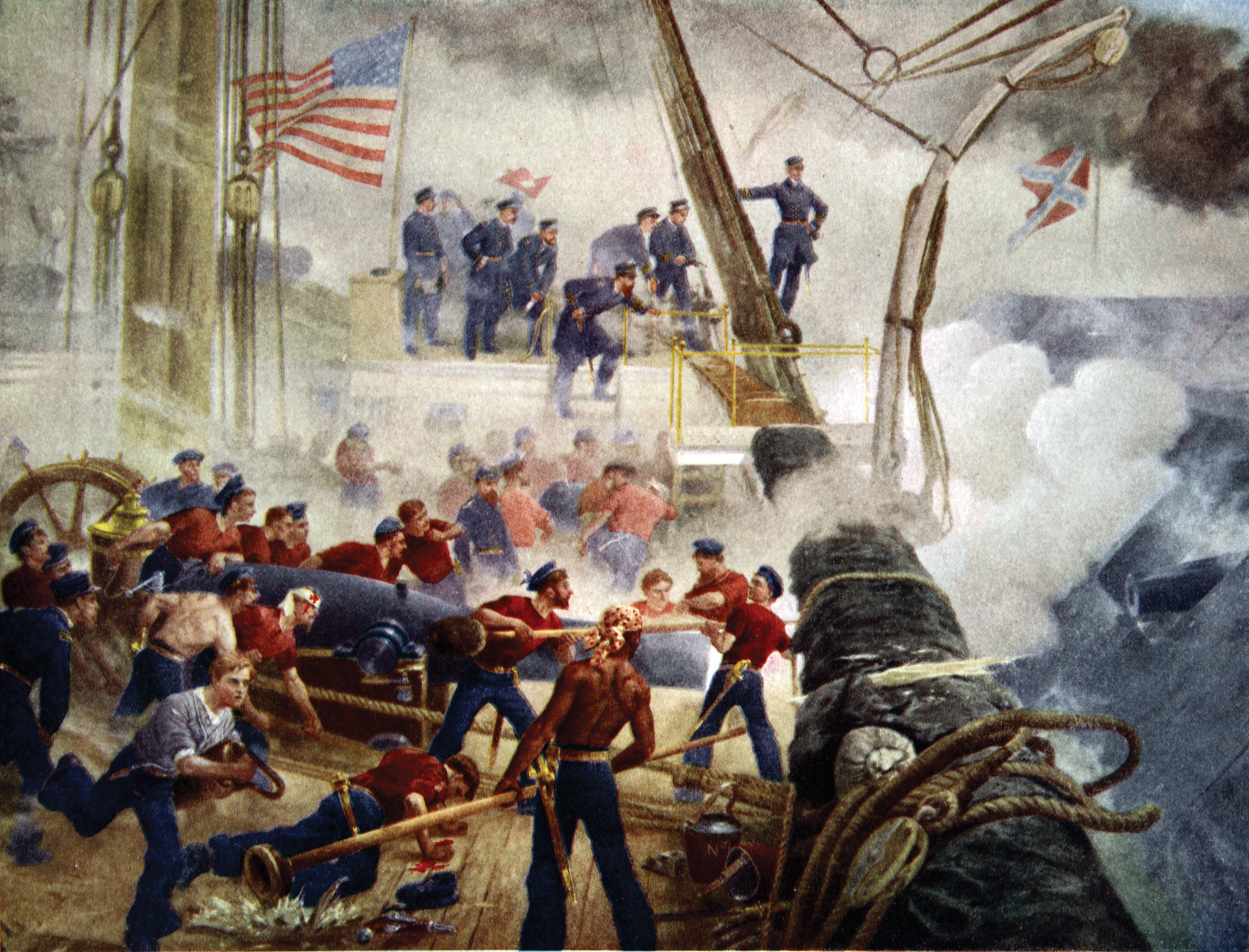

All three of the dreadnoughts lit up the night with massive 15-inch broadsides. Warspite fired at a range of 2,900 yards and Valiant 4,000.

Prince Philip saw “all hell break loose” as the British guns savaged their targets and shifted to new ones. “By this time the night was full of smoke, loud bangs and flashes and the dark shapes of our own destroyers, with their colored recognitions, appeared and disappeared. That bit of the Mediterranean then became a very dangerous place. There must have been some 20 British and Italian warships dashing about in every direction at high speed,” he wrote.

Five Warspite shells hit Fiume, and the cruiser burst into flames just aft of the bridge back to the after turret. The mammoth forward 8-inch gun turret was blown over the side by the explosion. On Zara, Corsi thought that Pola was firing on them in a case of mistaken identity.

On Stuart, Australian sailors watched Fiume as it “dissolved into a mane of shearing flame. She heeled, stricken under the onslaught, transformed in a few awful seconds from a proud fighting ship to a twisted tangle of iron.” Listing badly, blazing away, Fiume fell out of line. Sailors pulled out hoses to control the blaze but could not do so. Sailors hurled ready-use ammunition over the side to prevent it from exploding.

Zara never fired a shot in response—Warspite’s shells punched out her electrical system immediately. Worse, the 8-inch gun crews on the other Italian ships discovered that they lacked flashless charges, which meant that when they opened fire, they were temporarily blinded by their own guns firing shells.

In seven minutes Warspite had fired 40 rounds of 15-inch armor-piercing ammunition and 44 of 6-inch high explosive shells. In that barrage of ordnance, Cunningham was astonished that none of his own ships had been hit by friendly fire. “To my horror I saw one of our destroyers the Havock, straddled by our fire, and in my mind wrote her off as a loss. The Formidable also had an escape. When action was joined she hauled out to starboard at full speed, a night battle being no place for a carrier,” he wrote.

The blazing Fiume fell out of line and started listing badly. Her skipper, Captain G. Giorgis, ordered “Abandon Ship” at 11:15. The crewmen hurled rafts into the sea as the ship sank by the stern.

Zara blazed in the dark as well, spouts of flame reaching to the top of her masts. Her crew was ordered to abandon ship. Admiral Catteneo snarled, “The crew of Zara does not surrender. I have given orders to sink the ship.” The cruiser’s executive officer headed below to set off charges to scuttle Zara. At 12:30 am, they exploded, taking Admiral Cattaneo, her skipper, and much of her crew with her.

Other Italian ships suffered under the barrage of British shells as well. The destroyer Carducci roared with fires, and her skipper ordered her scuttled and went down with his command.

Soon Barham shells started dismembering Alfieri. The heavy British bombardment forced Alfieri’s skipper to order abandon ship. The destroyer’s skipper refused to enter a lifeboat. Instead, he calmly lit a cigarette and started to tend the wounded. Alfieri was the only Italian ship to fire back in the battle. She sank at 11:30 pm anyway.

Two destroyers were able to escape—Gioberti made a torpedo attack on the British ships that failed to score hits but bought time for her and her sister Oriani to flee the scene, with Oriani the only Italian warship to get away undamaged. Gioberti reached Calabria with one engine knocked out.

With the heavy lifting done, Cunningham ordered his destroyers to finish off the Italian cripples.

Havock moved among the burning and sinking Italian ships, using her torpedoes to finish off the cripples. She turned north to follow Cunningham’s orders, firing starshells to illuminate the scene. To the amazement of her skipper, Lieutenant G.R.G. Watkins, the starshells revealed a stopped and apparently undamaged ship before them. Watkins thought it was a battleship, but it was of course Pola, whose immobility had caused the action.

Havock opened fire at 11:45 pm and signaled (wrongly) that she had engaged a Vittorio Veneto-class battleship. Just after midnight, Watkins corrected his signal, properly identifying the target as an 8-inch gun cruiser and giving his intention to shadow the vessel, as he had no more torpedoes.

Fortunately, help was on the way. Captain Mack on Jervis and his eight destroyers were heading westward to find the rest of the enemy fleet. They had altered course northwest, unknown to him, increased speed, and opened the range. When Mack received Watkins’ signal, he turned back, figuring that a firm sighting in the hand was worth shadows in the bush.

It had been a rough night for Pola and her crew. The ship immobile and powerless, Captain De Pisa was extremely aware that his cruiser could offer no resistance to the British dreadnoughts that had torn apart the Italian ships that came to support him. De Pisa gloomily ordered the sea and condenser intake valves opened to scuttle the ship. Incredibly, the British had raced past her in the dark to blast the other Italian cruisers, seemingly uninterested in an immobile and dark vessel.

At 3 am, Mack’s destroyers came up to Pola, and Jervis came alongside with boarding parties mustered. The British pondered the possibility of towing Pola home but figured it would be too slow to drag through the Mediterranean, particularly with the certainty of heavy enemy air attack the next day.

With that, Jervis and Nubian fired two more torpedoes at the settling cruiser. Nubian’s torpedo was the coup de grace, as Pola exploded and sank at 4:03, ending the Battle of Cape Matapan.

Cunningham ordered his victorious ships to reassemble, and all were back together at 7 am. Cunningham ordered his ships back to the scene of victory, now to rescue survivors. They found an ocean covered by oil, and boats, rafts, wreckage, and corpses floating around. The British picked up about 900 Italian sailors, although some died later. A Greek destroyer flotilla that had been unable to join the battle due to a delay in ciphering orders pulled out 110 more.

The British were forced to withdraw when Ju-88s attacked the ships, with men still in the water. Refusing to press his luck, Cunningham withdrew. But first he shot off an aircraft from Formidable to Suda Bay with a message to be sent to Malta and then on a clear channel to the Supermarina in Rome, giving the location of the survivors still in the water, in a touch of old-style chivalry lacking in modern war.

The Italians promptly sent out the fully marked hospital ship Gradisca, and two days later she reached the scene, where she saved 13 officers and 147 men.

The Italian Navy had lost three heavy cruisers and two destroyers and suffered 2,400 casualties. Except for the Swordfish and its three-man crew lost by Formidable, the British had suffered no casualties or damage, to Cunningham’s great relief. In the melee, he had feared that Warspite had sunk one of his own destroyers.

Cunningham had won the first naval battle that involved carrier- and land-based aircraft, coordinating all elements extremely well. Matapan was an incredibly one-sided victory and gave the Royal Navy a moral ascendancy over the Italian Regia Marina for the rest of the war. While their submarines, midget submarines, torpedo boats, and aircraft would show ample determination and considerable courage in future battles, their main fleet would not sortie to engage any British force that included a battleship or carrier.

The victory was also won by Bletchley Park’s codebreakers, and they were very aware of what was going on. On the evening of March 29, John Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence, phoned Bletchley Park and asked to speak to Dilly Knox. Knox was unreachable, being at home, but Godfrey told Edward Clarke, who answered the phone, “Tell Dilly that we have won a great victory in the Mediterranean, and it is entirely due to him and his girls.”

The girls knew it. Mavis Lever said, “There was a great deal of jubilation in the cottage and then Admiral Cunningham himself came to visit us [a few weeks later]. The first thing he wanted to do when he came was to see the actual message that had been broken. Somebody rushed down to the Eight Bells public house to get a couple of bottles of wine, and if it was not up to the standard the C-in-C Mediterranean was used to, he didn’t show it when he toasted ‘Dilly and his girls.’”

Author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written on a number of topics and has maintained a website detailing the daily events of the war.