By Elmer Wisherd with Nan Wisherd

Elmer Wisherd was born on December 1, 1920, in North Dakota. Shortly thereafter, his family moved to a farm in Bruce, Wisconsin. When World War II broke out, he enlisted in the Army, hoping to become a pilot. That dream was not realized, but he became an aviation mechanic and, eventually, a crew chief on Douglas C-47 Dakota aircraft. This is his story.

I was inducted into the Army on September 12, 1942, and began my basic training at Bowman Field in Louisville, Kentucky. After basic, I was shipped to brand-new Alliance Army Airfield in the northwestern corner of Nebraska.

Because I had been a milk truck driver in Wisconsin, I was initially assigned to the motor pool—driving trucks and working on them. But I wanted to become an airplane mechanic and was assigned to mechanics’ school near Gulfport Army Airfield in Mississippi.

Every place we looked—every room in every building—were signs: YOU TOO CAN BE A CREW CHIEF. Most of us thought, ‘Yeah, you, too, can be a crew chief, but I can’t; that’s shooting pretty doggone high.’ But I did it.

After completing my mechanics’ course in September, I was shipped to Fort Benning, Georgia, where they put me to work on a great big Pratt & Whitney 14-cylinder engine—two rows of seven cylinders each in a circle—and I felt as green as green could be. At school at Gulfport, I had never seen anything like it! They told me to drain a sump on the carburetor. Where was that?! So I had quite a time. I imagine they figured I was pretty dumb, which I was.

Fort Benning was a big training camp. They were training paratroopers and training pilots to fly C-47 transports. The majority of the pilots at that time were staff sergeants who had enlisted.

As time passed, the pilots became warrant officers and then second lieutenants, with corresponding pay increases. I was still a corporal when I became a crew chief and began getting flight pay. Flight pay increased my paycheck by 50 percent.

As crew chief, I was responsible for my C-47 being ready to fly at all times. It was usually my job to turn the propellers before starting the engines but, occasionally, one of my assistants turned them. Before the airplane was started, we had to turn each propeller 14 times. (Because they were in a circle, some cylinders were upside-down.) Turning the propellers, and thus turning the cylinders, drained all the oil from the cylinders. If an engine started with oil in any cylinder, it would jerk the whole engine apart and would require a complete overhaul.

I had a list of items to check and, when I felt the airplane was ready for takeoff, I always started both engines before the pilot and co-pilot arrived. Before I started each engine, though, I hollered “Clear the prop!” so anyone near the engines could get out of the way.

We trained all day long. After takeoff, I stood between the pilot and co-pilot and watched the instruments. Then, as we approached our landing zone (LZ) or drop zone (DZ), I’d climb a ladder into the astrodome and watch for a signal from the lead aircraft. A green light meant “go.”

As the aircraft dropped low, the gliders or parabundles were released. Later, when we were practicing with paratroopers, I removed the back door so they could jump. Our C-47s could carry 18 paratroopers.

The paratroopers were constantly training, too. They had jump towers where they trained until they had advanced enough to join us and jump out of the C-47s. They all wore backpacks containing parachutes they’d packed themselves that were attached to static lines running the full length of the C-47. They also had a reserve chute strapped to the chest, which could be hand-operated in case their main chute didn’t open.

The jumpmaster’s job was getting the paratroopers out of the plane. He was generally at the rear of the plane, shoving out the paratroopers. The jumpmaster hollered “Jump!” or “Geronimo!” before shoving out the first paratrooper in line.

After the paratroopers were out of the plane, the crew chief—me—pulled the static lines back into the plane so they wouldn’t damage the side of the airplane.

I saw thousands of paratroopers drop while we were at Fort Benning, and our C-47 probably dropped hundreds nearly every day. As the weeks passed, those paratroopers were getting awfully good training and were landing real well.

After a short furlough home, I returned to my unit and in February 1944 was transferred to Baer Field near Fort Wayne, Indiana. We finally got our overseas orders. In February 1944, we flew from Baer Field to Macon, Georgia, then down to West Palm Beach, Florida; Puerto Rico; British Guiana; and Belem, Brazil, before crossing the Atlantic to Ascension Island and Roberts Field in Liberia, Africa. After Liberia, we flew to Marrakesh, Morocco.

It was a long haul. Twice we flew 11 hours without stopping. We put 8,464 gallons of gas through our plane, #43-15050, and it took us 19 days—811/2hours of flying time—to go from Florida to England. We had a little trouble with one propeller, and sometimes we had a little bit of bad weather, but we made it.

When we arrived, I was 23 years old and a buck sergeant—probably one of the lowest ranks of the sergeants that were crew chiefs of the airplanes. I was in charge of a huge C-47 that I had to work on and then fly in with the rest of the crew.

The airplane we had flown from the States had a large radar unit on the belly of the fuselage, and a commander took our airplane. I was transferred to another C-47—#42-100823. I looked it over, pre-flighted it, and got everything ready to go.

About that time, I saw two lieutenants walking toward me. I gave them a snappy salute, and they returned my salute. They walked into the airplane and the pilot, Al Johnson, turned to me and said, “Sergeant, when we’re out in public, you may salute. When we are in this airplane, I’m Al, he’s Joe, and you’re Elmer.” That was the way it was from then on.

Sam, my old radio operator from #43-15050, moved with me to the new aircraft that Al Johnson had named Ruca, after his wife, Ruth Callaway Johnson. Our destination: RAF Balderton, located two miles south of Newark-on-Trent and 15 miles northeast of Nottingham.

Most of the 439th Troop Carrier Group had arrived at Balderton on March 6, and we all lived in Quonset (Nissen) huts. Ours had no windows, but it did have a door on each end. It was unheated during the day, but we had a little potbelly coke-burning stove in the center of the hut for the cold nights. Cots closest to the stoves were prized, but we were never very warm. We dug trenches outside our hut so we had a place to go in case the Germans bombed us.

On March 18, the 439th was out doing a night flight and working on flight assembly when we got a signal that there were “bandits” in the area. Flight assembly was something we worked on practically every week, whenever we could get up and fly.

It began with the first plane taking off and circling the field while the other airplanes caught up and got into the flight assembly. When the signal came about the bandits, all planes immediately turned off their lights and landed back at Balderton as quickly as possible.

In 25 minutes, everyone from the 439th had landed. There were searchlights cutting through the night, bursts of flak and, to the east and northeast, there was quite a little firefight. Several bombs were dropped. I later heard that a couple English bombers were shot down that night.

We did a lot from the time we landed in England until Operation Overlord. We worked and flew both day and night. We had many flights where we delivered someone to another airfield. Al Johnson, Joe Fry, Sam Anbender, and I very seldom flew with a navigator. We flew by dead reckoning most of the time.

We also did a lot of paratrooper dropping. We would take a bunch of paratroopers up, flying around to simulate the time they’d be in the air before being dropped in France. These practice flights to the drop zone usually took 60 to 90 minutes. After we reached the DZ and the paratroopers had jumped, we’d fly back by ourselves.

Once in a while, though, the winds were too strong for them to jump safely without getting blown all over the place. When that happened, we brought them back with us. Did those guys gripe and holler then! They were not going to land in that damn airplane! They trusted their parachutes a heck of a lot more than they trusted our C-47.

I had to convince the jumpmaster that he needed to calm down the paratroopers. I also had to stand by the door, which we removed prior to the jumps, and make sure they didn’t take the door off and jump.

In April we moved to RAF Upottery, which was closer to the coast. The British were operating their fighter planes there, and we were at an airfield where we were operating only the C-47s of the 91st, 92nd, 93rd, and 94th Squadrons—about 70 planes. We were put in groups of three to six airplanes, and we were scattered over the 500-acre area. We were told that, if we were scattered, the Germans couldn’t come in and take out our complete group.

We went to London every once in a while. It had been bombed very badly, but the British didn’t act like anything was wrong. They seemed to think, ‘Well, so what? This has happened, we’ll live through it.’ And they did.

The Germans also had V-1 “buzz bombs” that came in and, as long as we could hear the buzz bomb above us, we had no worries. When the buzzing stopped, though, it was time to start worrying.

Operation Overlord

We did some heavy training at Upottery. We were getting ready for the big push—Operation Overlord, the invasion of France. The paratroopers were at our airbase by the middle of May, so we knew that sometime, somewhere soon something was going to happen.

On June 2, barrels of black and white paint arrived. The paint was to go on the airplane wings and fuselage in alternating stripes of black and white that went completely around the wing and completely around the empennage (the tail part of the airplane).

The reason for the striped painting was that, during Operation Husky (the invasion of Sicily), the troop carrier group was coming in with paratroopers in C-47s and some trigger-happy U.S. Navy gunners thought the C-47s were enemy bombers. They started shooting and many C-47s were shot down.

Painting our planes right before the invasion made them easy to distinguish from the German planes. I remember we used paintbrushes and brooms to paint the stripes. All of us painted the planes—all of the crewmembers, all of the mechanics. Everyone worked on painting the ships.

Our paint jobs must have been acceptable because the flight crews and paratroopers were all put into a heavily guarded restricted area on June 4. During that time, we could have anything—as many cigarettes as we wanted, unlimited candy bars, all the steak we wanted to eat.

This reminded me, the country boy, of beef cattle being put in a holding pen where they were given all the best quality food they could eat because they were being fattened up for the kill. We were definitely in the fattening pen. I guess when it came right down to it, they believed that most of us were eating our last meals.

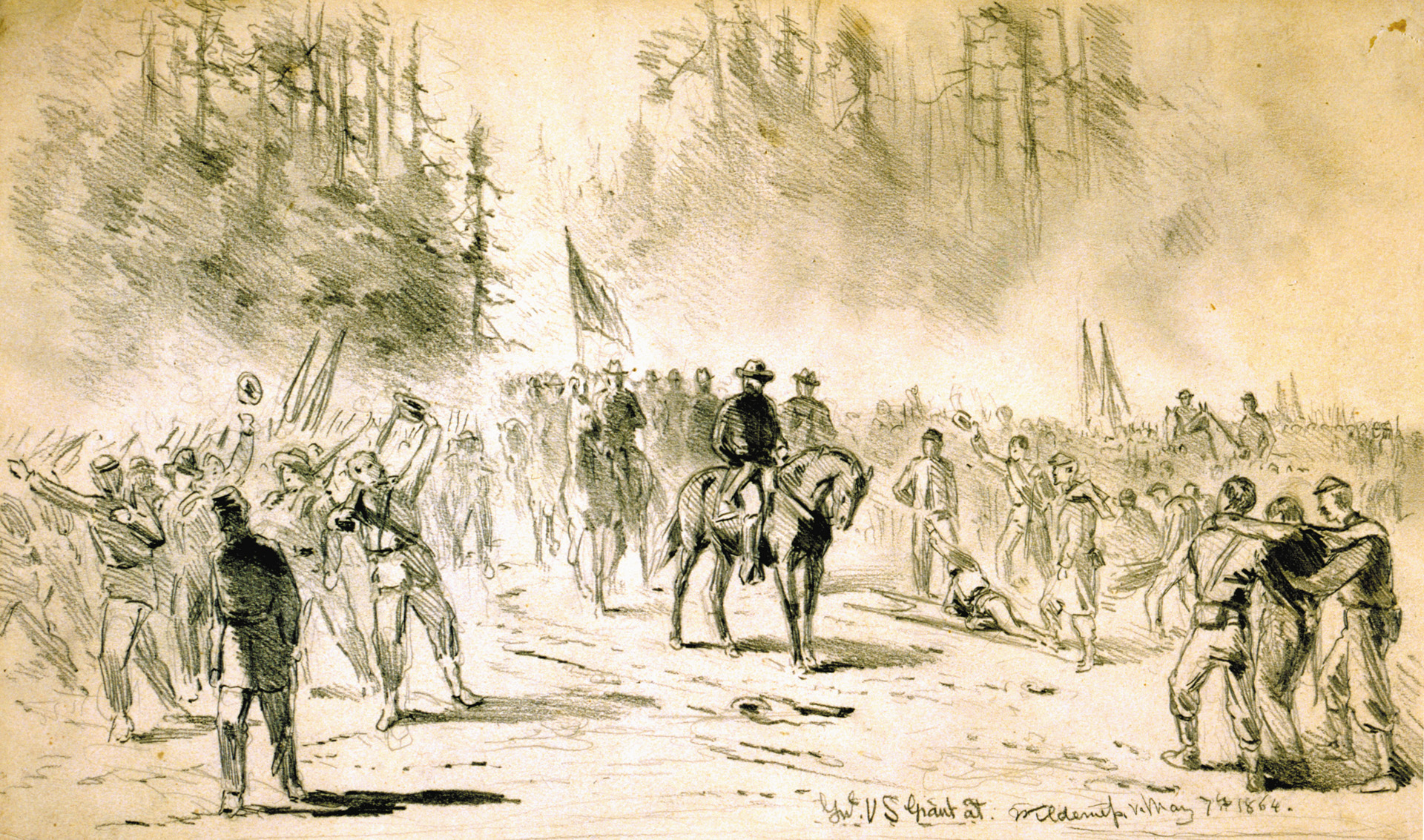

We were finished with our pre-training. On June 3, we did a pass-in-review of all the big wheels who had come to watch the 439th. I remember being in the parade and staying in step, but I had no idea why we did this.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was in charge of the invasion. We didn’t know this at the time, but the former prominent Wing Commander of the RAF told Eisenhower that he thought 50 to 70 percent of the troop carrier aircraft would be shot down in the upcoming Allied airborne assault.

Aircraft, including the C-47s being used as jumping platforms, had to fly low and slow, making them easy targets, as the tow ships and the gliders would be. They were unarmed, had little or no armor plating, and were without self-sealing fuel tanks.

Furthermore, because of the stiff German opposition on the ground, those who succeeded at landing, according to the RAF Wing Commander, would be quickly overwhelmed by the German ground forces.

After hearing this, Eisenhower still believed that plans for the invasion needed to proceed. Later, as the invasion began and Eisenhower watched the planes taking off for the French coast, he prayed, “May the Lord have mercy on their souls.” He believed the troop carriers, flying 600 feet above the ground and at only 110 miles an hour, would lose 70 to 85 percent of their C-47s and crews.

The weather was really bad, so we stayed all of June 5 in our restricted area with nothing much to do but eat and sleep. We were waiting for Eisenhower’s chief meteorologist, Captain J.M. Stagg, to figure out when the invasion could begin. Finally, Stagg told Eisenhower that we had an opening of a few hours for the invasion. Otherwise, it would probably be two or three weeks before weather would improve enough to launch the invasion.

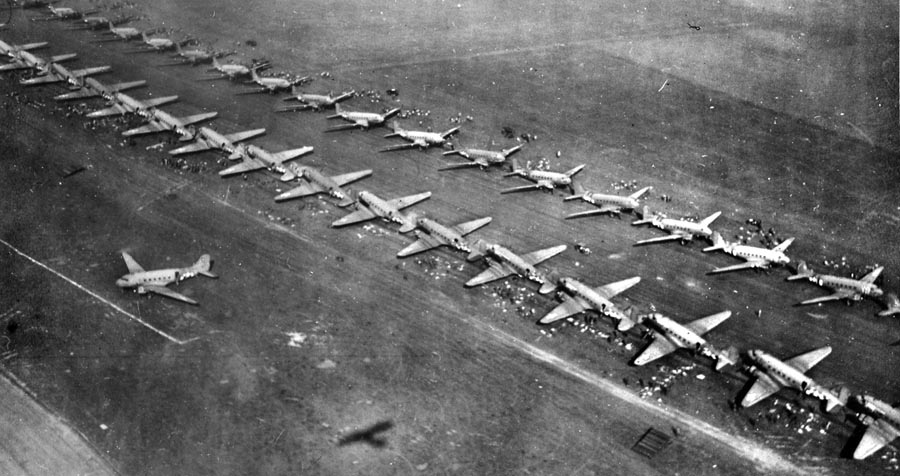

Scattered across England on 13 airfields were 801 C-47s and more than 13,000 paratroopers waiting to take off. Scheduled to depart 30 minutes before the main force were 20 C-47s. They would carry an advance group called “pathfinders” and would fly low—too low for radar detection. They would drop the pathfinders with lights, radio beacons, and brightly colored tarps that were used to create Ts or arrows to mark drop zones for the airborne force behind them.

During the hour before midnight on June 5, the sea was choppy, the wind was rising, and the clouds were beginning to form over the French coast.

At approximately 11:15 pm, our C-47 crews at Upottery began the final checklists and warm-ups. After that, the cockpit lights were turned off, and the pilots put on their wrap-around red glasses to help their eyes fully adjust to the darkness. After 15 minutes, the glasses were removed, the takeoffs began, and 81 heavily laden C-47s roared into the black night sky from Upottery.

We had practiced for months, taking off and circling above the field while another bunch of airplanes took off and caught up with the ones already in the air. The need for quick assembles and tight formation had always been stressed. We had practiced and practiced, and now we hoped our intense training would pay off.

We were scheduled to tow gliders and release them over Normandy; we would not be carrying paratroopers.

It is hard for me to describe how I felt and what I saw during the invasion of Normandy. It still seems amazing that this large mass of airplanes took off and ended up at their objectives at the right time. With what little navigation equipment and radios we had at that time, Operation Overlord is something that should have never succeeded.

One member of our squadron, John R. Phillips, described the invasion better than I ever could. He wrote, “My recollection of that night is really quite vivid. I remember, after briefing, being driven to the airplane where our sticks [the line of 18 paratroopers—maximum—within the plane] were already assembled and prepared for takeoff.

“Lieutenant John North was platoon commander, and we discussed jump speed and altitude. Since a group [the pathfinder planes] led by Charles Young had gone ahead, we had to have an altitude of greater than 1,000 feet above ground level. North requested that, if possible, we would descend to 500 feet above ground level (normal altitude for our jump was 600 feet) so his stick would have only one swing before landing.

“I agreed, with the provision that I would not break formation. The rest were informed by both me and North. North, of course, was the jumpmaster of the stick that was in his airplane.

“Just as we made landfall, turning into the DZ, we encountered low clouds and rain. My flight maintained good formation, but we lost visual contact with Morton’s right wingman. My navigator, Larry Wiles, saw that we were on instrument conditions and rapidly calculated our arrival time at the DZ. We broke out of the clouds but were unable to see Morton’s formation. Morton was leading another set of three….

“I asked Wiles where the pathfinder team was … and I put a lighted ‘T’ to show us which direction to go and where our drop zone was.… Wiles gave me an estimated time based on our airspeed to an approximation to the ‘T.’ When he told me we were two minutes out, I throttled back to 1,500 RPM, dropped down with my two wingmen to 500 feet, turned on the amber light in the cabin, and Wiles said, ‘This is close.’ I turned on the jump light and the sticks went out.

“My crew chief, Milton Wolf, was in the astrodome and confirmed that all the sticks in our Flight A were out. Just prior to the green light, I added power to the right engine, leaving the left engine at 1,500 [RPM]. The left engine was the side that the jump door was on, so we wanted to leave the left engine with no prop blast coming back on the paratroopers.

“We came under intense ground fire, and I saw Marvin Mirror being hit, and the right engine caught fire. He turned out to the left as we were told to do and descended for a night crash landing. When he turned out and I could see how badly the plane was burning, I broke radio silence and said, ‘Jump, Marvin! For God’s sake, jump!’ He didn’t, and I was horrified to see the plane hit the ground and explode.

“Within 30 seconds, we sustained a hit from the ground fire, and I felt my left foot feeling rather warm and squishy inside my shoe. I told [Bill] Ogletree, my co-pilot, to take the airplane, which he did.

“After we were out of enemy fire, I went back to the navigator’s table, took off my shoe and found my sock was quite bloody, and there was a hole in my foot. I put the sock and shoe back on since the bleeding was minimal at that point, but was beginning to hurt.

“Ogletree had turned back toward Upottery and flew the airplane until we had the field in sight at which point he said, ‘Sam, I can’t land it.’ So I tried a little pressure on the left rudder bar and found I could do it. We entered the pattern and I landed the plane, taxied to the wounded abort area, and was assisted by my navigator Wiles and Wolf to be taken to the 67th Hospital.

“The next morning I was operated upon and numerous bits of bullets and parts of the left rudder pedal were removed. Some of the material was so deeply imbedded that the surgeon was unable to remove some of the smaller pieces. Today, I still have a foot full of shrapnel and left rudder pedal.

“To deny fear would be a lie. Yes, I was afraid that we all would die, but to succumb to that fear and lose control of my airplane and my flight is bullshit.”

We made it back safely to Upottery. On June 7, we hooked up with a CG-4A glider; I don’t know what was in the glider. If the glider had a jeep, there would have been at least six men in it. If the glider had a trailer for the jeep, that trailer would probably have been loaded with ammunition or supplies along with six or eight men. Or, the glider could have been completely loaded with ammunition. We didn’t like to know what was in the gliders because, if it was a load of ammunition and got hit by a shell, it would make quite an explosion behind us.

We were one of 821 airplanes, lined up in five different groups, with the 439th being one of them. We were coming in three abreast with the lead plane in the middle, the left-hand wing, and our C-47 flying right-hand wing. We were all towing gliders. As we flew closer to the French coast, we began following another group of C-47s and gliders.

When our gliders landed, they were going to have some problems. The Germans had been expecting a glider and paratroop invasion, and they had flooded much of the land. Most of the open land not flooded was covered with “Rommel’s asparagus,” which were booby-trapped poles and stakes tied together horizontally and diagonally. Our gliders would have trouble finding safe places to land.

We joined a line of airplanes as far as I could see. Then I looked left and saw another big group of airplanes, probably the same size group that we were in. Another group of airplanes was moving in from the right and pulling into the same line we were in. Farther back behind this group was another group of airplanes, joining us in an ever-growing show of force. It was a sight that I’ve never forgotten.

The timing was so good, and the preparations were so good, that all of these airplanes could come in and line up and drop their gliders into these fields—some that were safe for landing and others that weren’t.

We released the gliders (the glider we were pulling could be released by the glider pilot or from inside the tow plane), and we had not been shot at. We then dropped low, and Al turned our C-47 back toward Upottery.

The tow rope, of course, was still trailing behind us, and we didn’t want to bring it back to Upottery, so Al said, “Elmer, this is your chance. Be a bombardier, release the tow rope, and see what you can hit.” As Al was buzzing over the treetops and houses, I found a target, reached up, and pulled the handle that released the tow rope. I don’t know if I hit the target or not.

We returned to Upottery and loaded our plane with food, ammunition, and first-aid equipment wrapped in parabundles. Then we strapped six parabundles to the belly of the airplane and flew back to France.

We flew two more missions on June 7 to resupply the troops. I remember flying toward the French beachhead and seeing many barrage balloons along the coast. There were ships near the coast, and many ships were unloading.

I remember movement on the beach, too, but most of the time I was busy with my job and had no time to think about anything else that was happening during Operation Overlord.

We spent the next few days resupplying our troops in France. There were days when we couldn’t fly, but we stayed busy whenever the weather was decent enough to fly.

On Saturday, June 24, we loaded up with resupplies and some nurses. Our mission was to land in France and take off again. They had bulldozed and leveled an area in a good-sized field. The field was wet and mushy, so they had laid metal planks—Marston mats—and hooked them all together for the length that was needed to land the C-47s.

We unloaded our supplies, and there were some wounded soldiers who came back to Upottery with us. We carried them into the plane on litters; sometimes we had two or three tiers of litters strapped to the inside of the plane. Some nurses stayed in France, and a few stayed with us and tended to the wounded.

Sunday was a repeat of Saturday. When I had time, I helped take care of the wounded as we evacuated them back to England. This went on into July.

On September 8, 1944, our 50th Wing was ordered to move to France, near Reims, to supply General Patton’s Third Army. We weren’t in France for many days, though, before we were ordered back to England.

We knew another big operation was coming, but we weren’t put in the restricted area this time. The Allied commanders probably believed that the Germans knew what was happening anyway. What was happening was Operation Market Garden, the invasion of Holland.

Operation Market Garden

On Monday, September 18, we took off at 10:30 am with paratroopers for the Holland invasion and drew fire as we hit the coast. Plenty of flak, all of it too high. Ruca was hit once but not bad. Just before we reached the DZ, we drew more fire. Some ships were hit hard but all returned.

The antiaircraft gunners determine at what altitude the airplane is flying and, at that altitude, the shell will explode. Because we were flying so low, the Germans didn’t have time to get an accurate aim, and the flak was all exploding too high. We were moving quite fast over the ground and canals—at about 160 miles an hour—and at perhaps 800 to 1,000 feet.

We picked up one bullet going over Holland. It was a 30.06, and it had come up through the tail of the airplane, ricocheted around for a while, and finally ended up on the pant leg of a paratrooper sitting in the airplane. He picked the bullet up, and it was hot as blazes. He was sitting there, blowing on it, and all the paratroopers hollered, “Get that damn door open!” As soon as we got hit with that bullet, I pulled the jump door out real quick. I often wondered if that paratrooper took that bullet back to the United States.

Some of the ships were hit once or twice, but nothing was too bad. Before we reached the drop zone, we drew more fire—flak and 20mm this time—and that was pretty heavy stuff. Flak makes one heck of a big puff of black smoke and, out of the black smoke, there might be nuts and bolts and razors and sharp metal flying in every direction.

We were so low (and this was scary) that we could actually see the Germans who were shooting at us. They were running around on the ground, picking up their clips of shells, and loading them into their guns. Then the bullets came flying past us, but we only saw the fifth or sixth ones. They were the markers, or tracers, so they could see where they were shooting.

We were pretty darn lucky that we got through there. Some ships were hit pretty hard, but the C-47 was a good old bird, and we all returned. One pilot was hit through the lungs, and one plane was hit through the hydraulic system, but they all got back to Balderton. We had no problems with the paradrop.

We were scheduled to have Wednesday off, so Al and Joe decided to go out and celebrate on Tuesday night. In the wee hours of Wednesday morning, however, we were told that we had a mission early that day. We had the parabundles filled, and we had our gear inside the airplane, but when we were ready to go, Joe Fry was so hung over that we had to help him into the airplane.

Joe was supposed to be the co-pilot, but he wasn’t going to be a co-pilot for a while—I knew that for a fact. So I got in the co-pilot’s seat with Joe in back on a stretcher, and we took off. As we were flying in formation across the English Channel, the pilot Al looked over at me and said, “Elmer, have you ever flown formation?”

“No, Al, I never have.”

“Well, you’re gonna have to—I’m too damn sleepy. I can’t make it.”

While Al was napping in the left seat, I controlled the throttles and the whole works and stayed in our three-plane formation. After a while, we all dropped below the fog to get our bearings and immediately drew some antiaircraft fire. Al woke up and took us up above the clouds so the Germans couldn’t see us.

About that time, Joe came staggering up from the back and asked, “Where are we?”

Al, fully awake now, answered, “I don’t know.” He handed Joe a map. “Find out where we are.”

Joe studied the map for quite some time, finally figured out that we were lost over Germany and sobered up pretty darn fast. He began studying the features on the map more closely while looking at the land below us. Finally, he found a river and told Al to follow it north. We landed safely in Brussels, Belgium.

Another C-47 had been hit, and one of its engines caught fire. The co-pilot of that ship immediately bailed out, and the fire stopped shortly after he jumped. (I think he landed safely but was taken prisoner.) The pilot landed back in England along with one other C-47 in our group of seven from the 91st Troop Carrier Squadron that had taken off that morning. The rest of us were reported as being shot down. Five out of seven airplanes missing on one mission actually wasn’t a very good record.

We left Brussels on Thursday and, on our way back to England, we got lost in the fog again. Fog is pretty normal around England; we sure didn’t see very much good weather while we were there. All five ships that had been reported as being shot down did get back, though.

On Saturday the 24th, we picked up a load of blankets and were supposed to deliver them to the Étain-Rouvres Air Base, an airfield known as A-82, near Verdun. Because of the weather conditions, we had to fly in formation at about 600 feet in altitude. The lead ship, #43-15050, had the only navigator. Our ship was flying right wing; Lieutenant Berry was flying left wing. The navigator in our lead ship missed the field at A-82 and took our three-plane formation over German lines.

All at once all hell broke loose and tracers were all over the sky. I was never so scared in my life. We didn’t even have flak suits on. I threw flak suits to everyone in our plane. I found out later that Lieutenant Berry, flying left wing, banked sharply to get away from the tracers, and our lead ship was hit.

The right engine of# 43-15050 was on fire and I found out later that, tied down on the floor of #43-15050, were dozens of highly explosive oxygen bottles. When the plane got hit, Berry hollered to the crew chief, “Get rid of those bottles!”

The crew chief cut the rope holding the bottles in place, and the bottles rolled to the back of the plane. Their weight put the airplane completely out of balance, put the nose high, and there was no way to keep the airplane flying on one engine with the nose that high. The only thing the pilot could do was try to maintain altitude until he could find a place to land.

Al radioed back that we would follow our lead plane until it landed, which we did. The pilot made a belly landing somewhere in France, and everyone on board was fine. I later heard that the airplane landed near an emergency field for the wounded—a Red Cross station—and they were in very dire need of oxygen bottles.

We took off again, somehow found A-82, and landed. We had blankets piled to the ceiling and had quite a job unloading them. We had just finished unloading when we saw a truck roaring toward us down the runway with its lights flashing. Inside the truck was the crew of #43-15050 that had just crash landed! We all piled into our plane and thought, ‘Oh boy, we have a navigator! We can get back to England now!’

We took off for England and were soon lost again. Really lost. We were calling “darky” [a request for directions] and we only had a half-hour of fuel left. Al told everyone to put on our ’chutes. He said we were going to make one more pass over England and, if we didn’t get directions, we were going to all bail out as Al pointed the plane toward the English Channel.

Just then, an English voice came over the radio and said, “Charlie-47, if you’ll take up a heading of….”

Well, by hit and by miss, we did finally get back to our airbase. It had been quite a day. No one will ever know how we came out alive.

On October 1, we moved to a base in France, three miles from Alençon and 20 miles north of Le Mans. We were living in tents again, but we had rain. Lots of rain. Our airstrip near Alençon was dirt that had been packed down by heavy equipment. It was covered with tarpaper and worked sufficiently unless it was raining.

During this time, we generally flew resupply missions. Our day usually began with a flight to Cherbourg, the port city we liberated in Operation Overlord. After loading our planes, we flew to various parts of France—wherever those supplies were needed near the front lines. We often had to unload the supplies, and we occasionally evacuated wounded soldiers.

On October 26, we moved again—Alençon to Châteaudun, about 70 miles southwest of Paris. It had been built as a French air base but was taken over by the Germans after the 1940 invasion. The Germans later based their Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighters there.

Châteaudun was pretty well bombed out. There were many, many hangars, but no hangar was intact. There had been huge craters in the runway where our bombers had dropped 500-pound bombs, but they had been patched and repaired. Still, it was a well-equipped field.

We were living in tents out in the flat land east of the airfield, and we had a water supply. We had no electricity, but we did have mess halls, and the food was good. We could use the materials we found from the abandoned buildings and planes, and we tried to make our living quarters as comfortable as possible.

During this time, we continued flying supplies to the Allied front and evacuating the wounded to hospitals in England. As Christmas approached, I thought about being in Fort Benning, Georgia, for Christmas just one year ago. So much had happened during the past year.

The Relief of Bastogne

Soon it became time for another big operation—the relief of Bastogne. In December 1944, American forces were in Bastogne, but the Germans launched their Ardennes counteroffensive and trapped the 101st Airborne Division in and around the town. We got orders to deliver supplies to them.

Shortly before we took off on December 27, headquarters had received word that the Germans had moved a flak gun into the area. Headquarters, though, did not fully communicate the extreme urgency of the situation to our mission commander before we left. The Germans had positioned their flak gun on a railroad crossing and had it zeroed in on the corridor they knew we would be flying. They also had 20mm, 30.30, and 30.06 guns, so they were ready for us.

We were flying a 50-ship mission towing gliders. The orders had been, “Get there as soon as possible.” Our primary mission was to deliver 76 tons of heavy ammunition, along with four surgeons. We had some fighters protecting us, but I saw two hit before we reached our LZ.

As we came in, the Germans opened fire. The black smoke made visibility almost impossible, but we had to stay in formation until we released our gliders. After releasing the gliders, we made a left turn. That was when all hell broke loose.

Flak was everywhere. The sky was just nothing but a big cloud of black smoke with our airplanes flying right smack dab into it. We were ducking, diving, and climbing all over the sky in that black cloud with flak exploding above us and ground fire below us. Flak was exploding so close that it bounced the airplane around, and we could hear the flak hitting it. One burst in half right in front of the windshield, scratching it as each half flew by but, luckily, the windshield didn’t break.

I got up on the navigator’s stool and, because we were in the front of the formation and were heading back, I was able to see the planes still trying to drop their gliders. I saw a plane get hit, and the left engine immediately caught fire. One crewmember jumped, and his parachute opened right in the flak. Two more jumped out, and their parachutes opened halfway down. One crewmember never came out, and the plane exploded the second it hit the ground.

Then I saw another plane blow up in the air. (I found out later that this plane was piloted by my buddy, Joe Fry, who had been my co-pilot since the past March when I arrived at Balderton Field, but on this mission they needed more planes and pilots. Joe was made first pilot and was placed in slot 13. Joe came back later, burned, but he and his crew all bailed out safely.)

John Hill, piloting the glider being towed by Joe Fry, later wrote, “About eight miles from the LZ, we started getting small-arms fire and, as we got nearer to Bastogne, the ground fire became heavier. I could hear the bullets hitting the heavy ammunition I was carrying, and I was praying that they would not hit the detonators that I had hanging next to my seat!

“Then something turned loose on us from underneath. It sounded like large antiaircraft fire. The towship then caught fire under the belly, and it blazed up suddenly over the whole back end. We flew for about three or four miles farther with the blaze getting larger all the time. It looked as though the towship would blow up any minute, it was burning so furiously.

“I realized Joe was trying desperately to get me over the LZ. Flames were leaping back halfway down the towrope. Two ’chutes came out through the flames. After another mile, I thought I could make it to the LZ. Around the time a third ’chute appeared, I cut loose and cut across to the LZ.” Hill’s glider made it safely down.

Our mission on December 27 successfully delivered 70 percent of the cargo destined for Bastogne, but it came with the highest percentage of losses for any mission flown during the war. Of the 50 C-47s that took off from Châteaudun that morning, 13 were shot down, one crashed, and two were damaged beyond repair. Another 15 ships were damaged but eventually flew again.

Eighteen C-47 crewmembers lost their lives, and 21 became POWs. Three glider pilots died, and 14 glider pilots became POWs. Fourteen C-47 crewmembers were injured but returned to Châteaudun on December 27.

Colonel Charles H. Young later wrote about the mission to Bastogne, “Troops on the ground [at Bastogne], their eyes fixed on the drama taking place a few hundred feet above them, held their breath as pilots followed each other doggedly into the murderous German flak concentration, now locked in on the narrow column.”

Later, a captain who had witnessed the carnage, stated, “No ‘show’ I have ever seen, or will ever see, compares to this spectacle, and this includes the armada of Normandy on D-Day. Nothing compares to seeing those fellows marching headlong through that intense flak.”

After this adventure, I was transferred to B-24 school back in England. I didn’t much care for B-24s; most of them had leaky gas tanks, and that gas dripped down into the bomb bays. Before landing, the bomb bay doors had to be opened hydraulically to remove the gas fumes before lowering the landing gear. If the landing gear was lowered first, it created electrical sparks that could ignite the gas fumes in the bomb bays. I had seen a B-24 pilot lower his landing gear with the bomb bay doors closed, and his plane blew sky high.

Once my training was done, it was back to Châteaudun, but I was returned to my C-47 group and not assigned to B-24s. Soon we were preparing for Operation Varsity, which occurred on March 24, 1945, and was the last major airborne assault in Europe during World War II.

Operation Varsity

Varsity was also the largest airborne operation in history to be conducted in one location on a single day—with more than 17,000 paratroopers ,836 aircraft, and 1,348 gliders involved. Varsity’s goal was to establish a stronghold on the east side of the Rhine River and support the Allied troops as they crossed the river.

We had been put in the restricted area again, so we knew something big was going to happen. I was on guard duty at the compound on March 22 and 23. We took off at 9:30 am on March 24.

As we were flying along, the new engines, because we hadn’t had time to break them in properly, were heating up. The air-cooled engine of the C-47 has cowl flaps that could be completely opened, completely closed, or left halfway open. These engines were “in trail,” meaning that our air speed dictated the position of the cowl flaps.

I told the pilots that they had to get the cowl flaps open or the engines were going to blow up. They said, “Well, if we do that, we’re going to burn too much gas.”

I shot back, “If you don’t open those cowl flaps, our engines are going to blow up, and you’re not going to need gas. Open those cowl flaps and get those engines cooled down.” They complied and we made it to the landing zone.

As we flew toward our LZ, there was plenty of sweating going on, and plenty of shooting, but no hits on my airplane. We were very lucky, because we were pulling two loaded gliders at only 90 miles an hour.

Talk about ships going down and burning on the ground! I had never seen as many airplanes burning on the ground as I did during that flight. That was because many of our pilots were flying C-46s, and the C-46s are controlled by hydraulics. (The C-47s are controlled with cables.) When the hydraulic lines of the C-46s were hit, the pilots lost control of their planes. When they lost control, there was nothing they could do but crash.

Later I heard that, once the tow planes starting coming in with their gliders, it was three hours of nonstop formations before everyone had passed by. Like we did at Normandy, everyone stayed in close formation, and it was an overwhelming sight.

After we dropped our gliders, no one had enough gas to get back to our base, so we all landed at alternative airfields. A number of planes landed with no rudder, some didn’t have elevators, and others had holes in the wings that you could stick your head through. Many had holes in their fuselages.

Many C-46s would have crashed—and did—with these hits, but our dependable C-47s kept on flying. Many called the C-47 the “workhorse of the air.” A number of planes that landed at the airports didn’t leave for quite a few days or even months, depending on the repairs they needed to be flyable again.

Varsity was my last combat mission, but we still ran resupply and evacuation missions. As the war came to a close, we usually flew two flights a day into Germany, and we saw some terrible things while we were picking up prisoners of war. In some camps, the prisoners were nothing but skin and bones, and their clothes were hanging on them. We had to carry some of them into the plane and strap them in litters. Others could walk okay but needed some assistance. In other camps—maybe the actual POW camps—the guys were in good shape. All of the prisoners were pretty darn happy to be free.

After the war ended, I returned to the States. Even though I had liked the job I had—I loved being an airplane mechanic and I loved flying with the pilots—I thought that I had had enough. I was discharged on September 16, 1945, as a Tech Sergeant with a base pay of $135 per month, plus flight pay.

When I think back to my time in the European Theater, I sometimes remember the many close friends who died. We all made close friends, we lost some of them, but we had to keep going. We had an important job to do, and with the next day came the next mission. Our ground forces were counting on us to deliver the supplies they needed, and we all worked together to defeat Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany.

Now, we have the time to remember our friends, who made the ultimate sacrifice for our country. They should never be forgotten.

When we landed the C-46 for the last time on July 20, 1945, I walked away, determined to never fly again. Seeing my buddies shot out of the sky, and praying with every mission that our C-47, our Ruca, would safely return to the airfield, was still too vivid in my mind. That day, however, I didn’t realize that my fascination with flight was still very much alive.

After the war, Wisherd became a school bus mechanic but, despite his stated desire to never fly again, he found that he missed aviation. He got his civilian pilot’s license, maintained and flew private planes, served as a flight instructor, became the operator of the Rusk County Airport in northwest Wisconsin, and started the Lake Flambeau Flying Service. This article was adapted from his memoir, Clear the Prop, published in 2018 by Cable Publishing.