By Roy Morris Jr.

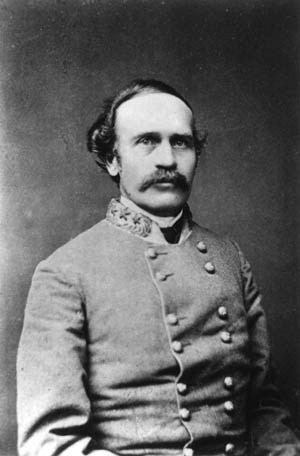

Of all the unlikely heroes of the Civil War, none was more unlikely than Bushrod Johnson, Ohio-born Quaker turned Confederate general. A quiet, self-effacing man, it was Johnson’s destiny to lead one of the most spectacular charges in American history at the Battle of Chickamauga, a charge that very nearly altered the course of the war. Yet the day before Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Lee would publicly humiliate Johnson and remove him from command for a momentary lapse of courage. It was a characteristic ending for Johnson, who more than most men was his own worst enemy—unless, as it sometimes seemed, fate itself was his ultimate foe.

A Quaker Goes to West Point

Johnson was born on October 7, 1817, on a small family farm in Belmont County, Ohio. His parents, Noah and Rachel Spencer Johnson, were Quakers, part of a large community of Friends who had immigrated to Ohio in the early 1800s from the slaveholding states of the Upper South. The Quakers were morally opposed to slavery, and they were just as adamantly opposed to war, paying a special government tax to avoid military service. Nevertheless, at the age of 17 Johnson decided to seek appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He had been living for the previous two years with his brother Nathan’s family in the village of Belmont and teaching school in nearby Barnesville. But teaching, then as now, was a poorly paid profession, and Johnson had no desire to become a farmer like his father or a doctor like his brother. A military career, with free education, travel, and the promise of adventure, seemed like the perfect choice for an ambitious young man with little money and few connections. The fact that he had been raised a Quaker was merely an inconvenience for Johnson—the first of many times he would rebel against his basic nature.

Despite Nathan Johnson’s strong objections, Bushrod somehow managed to secure the coveted appointment, entering West Point in the summer of 1836 as part of the famous Class of 1840. Among his classmates were a red-haired fellow Ohioan named William Tecumseh Sherman and a stolid old-line Virginian named George Henry Thomas. Like many of their fellow cadets, the trio would face a difficult decision when the time came to choose sides in their country’s bitter civil war.

At West Point, Johnson proved to be an indifferent cadet, reflecting perhaps his ambivalence as a Quaker studying to become a soldier. His class standing dropped steadily during his four years at the academy, and he drew numerous citations for such minor infractions as loitering, keeping an untidy room, and swearing. Still, Johnson was consistently promoted, rising from cadet corporal to sergeant and finally to captain. Among the lower classmen serving under him were several future generals destined to play important roles in his life: James Longstreet, William Rosecrans, Richard Anderson, and Ulysses S. Grant. Johnson graduated from West Point on time in 1840, ranked 23rd in a class of 42. His highest marks were in infantry training, his lowest in ethics. It was an accurate, if unhappy, forecast of his future career.

Bushrod Johnson in the Mexican-American War

Johnson entered the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Infantry Regiment, Andrew Jackson’s old command. From the start he demonstrated a dubious ability to obtain more than the usual amount of leaves, a proclivity that adversely affected both his chances for promotion and his staff assignments. At Fort Stansbury, Florida, Johnson served as assistant commissary of subsistence, a dreary paper-shuffling job that offered no chance for quick advancement or adventures. Later, at the comparatively posh Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, he remained in the background, taking no part in the post’s active social life, although fellow lieutenants Longstreet and Grant both courted their future wives while serving at the base.

In 1845, Johnson traveled to Texas as part of Brig. Gen. Zachary Taylor’s Army of Occupation. In the ensuing war with Mexico, Johnson saw action at the Battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey, where the 3rd Infantry was conspicuous in the savage street fighting. But amid the welter of young officers winning plaudits and promotions, Johnson’s name was conspicuously missing. Mainly this was due to his less-than-sterling attendance record: in the first nine months of 1846, while his regiment was actively engaged in battle, Johnson missed nearly seven months of duty with a dubious string of minor physical ailments, including a persistent case of swamp fever. He fought well enough when he was present, but others had been, and continued to be, present from the start.

In March 1847, Johnson took part in General Winfield Scott’s famous amphibious landing at Vera Cruz. There, as the army settled into a lengthy siege of the Mexican bastion, Johnson again was appointed assistant commissary, a particularly thankless job under the prevailing circumstances. Overworked and underpaid, Johnson was responsible for the unloading, storing, and distribution of all food supplies to the 13,000-man army. After the surrender of Vera Cruz he was given the additional burden of issuing rations to thousands of starving Mexicans within the captured city, ominously known as the City of the Dead for its periodic outbreaks of yellow fever. Johnson himself contracted the usually fatal illness and nearly died that spring.

Resignation Over Court Martial

Weakened by his near-fatal bout of yellow fever, Johnson was easy prey for unscrupulous traders who approached him about assisting them in procuring and transporting supplies into the stricken city. On July 1, 1846, he wrote an ill-advised letter to his immediate superior in New Orleans, Major Washington Seawell of Virginia, promising him a healthy cut of the profits in return for shipments of flour, soap, and candles. Johnson compounded his grievous error of judgment by openly suggesting that the supplies be disguised as government shipments. Seawell, who scarcely knew Johnson, immediately sent a copy of the letter to the adjutant general in Washington, who in turn recommended that Johnson face a military court of inquiry.

Johnson hastened to the capital to plead his case, such as it was. In a letter to President James K. Polk, he admitted approaching Seawell with the offer but attributed it to his weakened physical condition and the burdens of his job as commissary. “It is the aggregate of a man’s acts throughout the court of a number of years, and not a single fault totally disconnected with any precedence that indicates the character,” he wrote to the president. The punctilious Polk was unconvinced. In recognition of Johnson’s seven years of service, however, he was permitted to resign rather than face a public court martial.

A Teacher at Western Military Institute

Suddenly out of work at the age of 30, his military career in shambles, Johnson fell back on the only other profession he had known, that of teaching. Capitalizing on his West Point education, he secured a post on the staff of the Western Military Institute in Georgetown, Kentucky. WMI was one of many military academies in the prewar South, and Johnson, as a former army officer with actual combat experience, got along well with the faculty and cadets. By 1850 he had become school superintendent, and two years later he married 24-year-old Mary Hatch of nearby Drennon Springs. The birth of their son, Charley, in 1854 was tinged with sorrow. Charley was born sickly and mentally impaired.

In 1855 the financially challenged WMI relocated to Tennessee, where it became affiliated with the University of Nashville. Once in the Volunteer State capital, the school began to thrive. Johnson, for the first time in his life, achieved a measure of financial success. But his world darkened again three years later when Mary died unexpectedly of fever, leaving her grief-stricken husband alone to care for their handicapped son. Johnson purchased a double burial plot in Nashville’s Old City Cemetery, and there he buried his wife of six years.

WMI continued to prosper during the last years of the decade, even as the country moved ever closer to civil war. In 1859 the graduating class presented “Old Bush” with an engraved sword in appreciation of his work as school superintendent. One of the graduating cadets, Smyrna, Tennessee, native Sam Davis, would be hanged as a Confederate spy four years later in Pulaski, mere miles from his boyhood home.

Siding With the South

The school shut down for good in the spring of 1861, soon after the firing at Fort Sumter ushered in the Civil War. In May, Johnson was commissioned a major in the state’s provisional army. Prior to assuming his post, he took Charley to stay with relatives in Indiana. In the not unlikely event of his own death, Johnson sought to insure his son’s future by purchasing land in Illinois and Kansas and deeding the property to Charley. Then, as the current saying had it, he “went south.” Throughout the course of the war, Charley was encouraged by his Hoosier relatives to believe that his father was fighting to preserve the Union.

Johnson’s reasons for choosing the Southern cause were pragmatic rather than ideological. At the outset of the war he was a relatively wealthy man, respected as an educator by Nashville’s leading families. Beyond that, the shadow of his forced resignation from the U.S. Army precluded any hope of reenlisting in the North. Unlike his former classmates Grant and Sherman, who had resigned to enter private business (although Grant faced some ugly rumors of his own about drunken behavior), Johnson could not have reclaimed his former commission; his Mexican fiasco was still on file in Washington.

Fiasco at Fort Donelson

Instead, in February 1862, as a newly commissioned Confederate brigadier general, Johnson traveled to Fort Donelson, Tennessee. There he was thrust into a tragicomic affair involving the precipitate surrender of the fort by his panicky superiors, Brig. Gens. John B. Floyd and Gideon Pillow. As the fort was being surrounded by Union forces, Johnson led a spirited counterattack. The attack seemed on the verge of success when Floyd and Pillow—without bothering to notify Johnson—suddenly ordered his men to fall back. Fiery cavalry Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest urged Johnson to renew the assault. But Johnson, now understandably perplexed, hesitated to overrule his commanders. That hesitation sealed the garrison’s doom.

That night Johnson was absent from a conference between Floyd, Pillow, and Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, where it was decided to surrender the fort. First Floyd, then Pillow, declined to accept responsibility for the act, and it fell to Buckner to direct the Confederate surrender. The next morning Johnson was sent to escort Union negotiators, including Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace, later author of the bestselling novel Ben-Hur, to Confederate headquarters. Then, while Buckner was forced to accept humiliating unconditional surrender terms from his good friend Grant, Johnson carefully faded into the background. For three days he kept out of sight while Buckner and the Union officers arranged for the transportation of 12,000 Confederate POWs to Northern prison camps. While Buckner, Grant, and their staffs were dining together at Buckner’s headquarters, Johnson carefully avoided all contact with Grant or other Union officers who might have recognized him from their old Mexican War days. After watching his men loaded onto steamboats for the long trip north to prison, Johnson concluded (with a fair degree of self-interest) “that it was unlikely that I could be of any more service to them.” Then, in the company of a young captain who had been one of his students at WMI, Johnson casually walked into the woods and escaped.

Who Killed General Sill?

Rejoining the army on its retreat from Nashville, Johnson commanded a brigade at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. On the first day of fighting, he was thrown to the ground and knocked unconscious by a shell that exploded directly beneath him, killing his horse. At first it was feared that Johnson was mortally wounded, but he recovered in time to take part in General Braxton Bragg’s ill-fated invasion of Kentucky later that year. At the Battle of Perryville in October, Johnson’s brigade led the assault on the Union center near the H.P. Bottom House alongside Doctor’s Creek. Again Johnson performed courageously, having five horses shot from under him, but misfortune again bedeviled his efforts. At the very point of victory, his brigade ran out of ammunition, and Brig. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s Arkansas troops rushed into the gap and won the lion’s share of the day’s honors instead. For his part in the battle, Cleburne was promoted to major general—neither the first nor the last time that Johnson would be passed over for promotion by the Confederate brass.

At the Battle of Stones River two months later, Johnson’s brigade again behaved admirably, suffering heavy casualties in the fierce winter fighting. In keeping with his usual misfortune, Johnson soon became embroiled in a controversy with fellow general St. John R. Liddell over which man’s brigade had overrun an important Union position and killed Ohio general Joshua Sill. Johnson angrily demanded that the case be submitted to the Confederate secretary of war; he wanted “justice done to those who have a right to expect it at my hand.” The matter was left in the hands of division commander Cleburne, who wisely sidestepped the issue by simply stating in his report that both generals were “contending for the honor” of having killed Sill and captured his position.

Bushrod Johnson’s Charge at Chickamauga

As at Perryville, the Confederates retreated after the Battle of Stones River, leaving the Federals the technical victors. Johnson continued to command a brigade under Bragg during the army’s withdrawal from Middle Tennessee in the spring and summer of 1863. In September he was given command of a division as Bragg began laying a trap for Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans—another of Johnson’s old classmates—in the North Georgia woods below Chattanooga. On the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga, September 19, Johnson’s men took part in bloody but indecisive fighting. That night his old associate from the peacetime army, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, arrived by train from Virginia to assume command of Bragg’s left wing, which included Johnson’s division.

The next morning, as Confederate attacks on the Union left continued to be fruitless, Longstreet placed Johnson’s men at the front of a massive column of assault 400 yards east of a log cabin known locally as the Brotherton House. With Johnson’s old brigade in the forefront, the Confederates surged forward shortly before 11 am, and Bushrod Johnson entered the history books.

Immediately prior to Johnson’s attack, a harried Rosecrans had received an erroneous report of a gap in his lines. Without bothering to check the accuracy of the report, Rosecrans summarily ordered a realignment of troops already in place. At the very moment the unnecessary realignment was under way, Johnson’s gray-clad infantry crashed into a newly created gap near the Brotherton House and shattered the entire Union right at a single stroke. In less than 50 minutes the Confederates, with an exultant Johnson leading the way, drove the Union right completely from the field, sent Rosecrans and his staff galloping in headlong flight, then wheeled to assault the Union left, which was massing in desperation on a low elevation called Snodgrass Hill. Never again would Johnson, or the Confederacy, know such total success.

In his official report, Johnson gave an eloquent and emotional account of the charge. “The scene now presented was unspeakably grand,” he wrote. “The resolute and impetuous charge, the rush of our columns sweeping out of the shadow and gloom of the forest into the open fields flooded with sunlight, the glitter of arms, the onward rush of artillery and mounted men, the retreat of the foe, the shouts of the hosts of our army, the dust, the smoke, the noise of firearms—of whistling balls, grapeshot or bursting shells—made up a battle scene of unsurpassed grandeur.” Ever mindful of the men he commanded, Johnson added: “I may be permitted to say for these noble men, with whom I have been so long associated, that I then felt that every man in the brigade was a hero.”

That morning at Chickamauga would prove to be the apex of Jonson’s career, as it was for the entire Confederate Army of Tennessee. Ironically, only the stalwart defense of Snodgrass Hill by Johnson’s old West Point classmate George H. Thomas, a Virginian who was disavowed by his family for remaining loyal to the Union, prevented a Southern triumph of unprecedented proportions. Had Bragg followed up his hard-won victory by recapturing Chattanooga, the entire course of the war might have changed. Instead, to the disgust of many, including Johnson, Bragg settled into a two-month-long siege of Chattanooga. Johnson joined other generals in signing a petition calling for Bragg’s ouster, but Jefferson Davis, a personal friend of the embattled commander, declined to heed their prescient advice. Instead, many of the unhappy generals were sent away from Bragg’s army instead, at the worst possible time for the Confederates.

Johnson in the Army of Northern Virginia

Immediately prior the army’s stunning defeat at Chattanooga in late November, Johnson was detailed to join Longstreet for an attack on the Union garrison at Knoxville. The failure of that attack, coupled with Bragg’s retreat from Chattanooga into Georgia, led Longstreet on an arduous return trip to Virginia. With him went Johnson’s brigade. As the weather turned bitter in the East Tennessee mountains, many of the Confederates were without shoes or blankets. Ever solicitous of his men’s well-being, Johnson ordered a four-day delay while dozens of cobblers were put to work making new shoes for the suffering men.

As a stranger entering the clannish Army of Northern Virginia, Johnson did his best to be of use, helping to turn back a Federal attack at Drewry’s Bluff in May 1964. That same month he was finally promoted to major general after two years of official recommendations, legislative resolutions, and personal letters from his superiors. Soon afterward he found himself involved in yet another dispute with a fellow officer. Following Grant’s first unsuccessful thrust at Petersburg in June 1864, Johnson read in a Richmond newspaper that Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise’s Virginians had presented their state with a stand of captured Union colors. Johnson, irate, fired off a letter to government officials in Richmond protesting the action and noting that it was his Tennesseans, not Wise’s Virginians, who had captured the Union battle flags in the first place. “My object,” wrote Johnson, “is simply to insure that a body of gallant and meritorious men are not bereft of the rewards of their heroic deeds and to procure the restitution of trophies that belong rather to the Confederate government than to any particular state.” Wise, enraged and embarrassed, vowed revenge.

That July, Johnson showed himself to poor effect before General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of the Crater, where his hesitation to counterattack permitted Virginia brigadier William Mahone to take the initiative and claim credit for the Southern victory. The ever-audacious Lee would remember Johnson’s unaccountably timid performance with distaste.

As the war in Virginia bogged down into dismal trench warfare with no hope for ultimate success, Johnson was not alone in seeming to lose heart. His personal bravery was undoubted; he had been wounded at Shiloh, had five horses shot from under him at Perryville, been in the thick of the fighting at Stones River, and spearheaded one of the greatest breakthroughs of the war at Chickamauga. But now, after four long years of warfare, Johnson was mentally, physically, and emotionally spent. With his old brigade of Tennesseans scattered among other commands, Johnson felt isolated and friendless among Lee’s coterie of aristocratic Virginians.

Johnson’s Career Ends in Disgrace

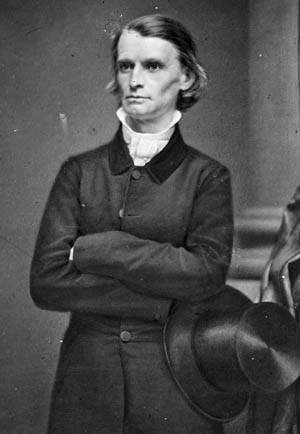

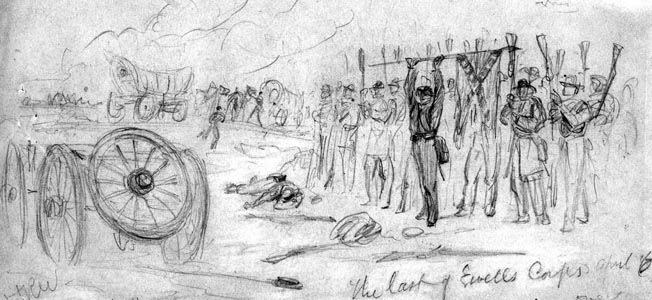

In April 1865, following the fall of Petersburg and Richmond, Lee began his last desperate race for supplies at Appomattox. Johnson joined the ragged procession of Confederates seeking to escape the massive Union juggernaut that now was bearing down on them from all sides. On April 6, at Sayler’s Creek, Johnson’s troops, along with those of Maj. Gens. Richard H. Anderson and George E. Pickett, came under withering attack by much more numerous Union forces. In the unequal melee the Confederates broke and ran, and the three generals joined their men in a panicky dash for safety. Johnson unwisely made his way to Lee’s headquarters to report the rout. But Lee, perhaps recalling Johnson’s poor showing at the Crater the year before, refused even to look his crestfallen subordinate in the eye. Waving his hand dismissively toward the rear, he said tartly, “General, take these stragglers to the rear, out of the way of Mahone’s troops. I wish to fight here.”

A savvier individual, faced with such a caustic rebuke from the normally mild-mannered and scrupulously polite Lee, would have been careful to avoid further notice. But Johnson, with no place else to go, was still on hand the next morning when his bitter rival Henry Wise arrived with the remnants of his division still intact. Lee, hearing Wise loudly denounce those generals who had left the field, ordered him to take command of Johnson’s troops. While Wise enjoyed an unexpected 11th-hour triumph, Johnson sat alone, burning with shame and enduring sidelong glances of disapproval from his fellow officers. The next day, less than 24 hours before surrendering to Grant at Appomattox, Lee somewhat vindictively ordered Johnson, Anderson, and Pickett dismissed from the army. Johnson’s second military career, like his first, ended in dismal failure and official disgrace.

Johnson’s Return to Civilian Life

If Johnson entertained hopes of commencing a happier postwar career, he was soon disappointed. The last years of his life followed the dismaying pattern of the first. Returning to Nashville, he entered the real estate business, attempting to augment his meager savings through investments in such dubious money-making schemes as an improved churn, improved soap, a cement-making plant, and a paint-producing factory. None of the ventures succeeded, and Johnson was forced to sell his remaining property in Nashville to pay living expenses for himself and Charley, whom he had taken back into his care at the end of the war.

In 1870 Johnson returned to the scene of his greatest happiness as principal of the newly created Montgomery Bell Academy at the University of Nashville. The school, headed by former Confederate general Edmund Kirby Smith, flourished for a time, but a nationwide depression in 1873, coupled with a local cholera epidemic, compelled the academy to close its doors. Bitterly disappointed, Johnson took Charley and retired to his last remaining piece of property, a ramshackle farm purchased from his niece in Macoupin County, Illinois.

Macoupin County had furnished a large contingent of volunteers to the Union cause during the war, and residents there were less than thrilled to find a former Rebel general living in their midst. Johnson’s closest neighbor, John Andrews, who had a lost a son in the war, refused even to speak to the unwelcome arrival. Andrews’ brother-in-law, however, former Union Colonel Jonathan Miles, took pity on the isolated Johnson and befriended him. Ironically, Miles had been serving on the Union right at Chickamauga when Johnson’s attack sent him flying to the rear with the rest of his comrades on that part of the line. Johnson also found a friend in Andrews’ son, John, who was about the same age as Charley. The younger Andrews was an avid student, and Johnson frequently loaned him textbooks and quizzed him carefully about his reading.

Johnson liked to think of the farm as a temporary haven while he wistfully planned a move to California, but it was not to be. In the summer of 1880, the 62-year-old Johnson suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving him speechless and paralyzed. He lingered for weeks, neither he nor his mentally challenged son being able to tell anyone about the general’s long-purchased burial plot in Nashville. Johnson died in September 12 and was laid to rest in the cemetery of Mils Station Methodist Church, unmourned and unattended by any former Confederates. It was left for the Union veteran Miles to pay for a headstone and monument. On the monument was inscribed the verse: “A valiant leader, true hearted and sincere/An honored solider, who held his honor dear/A cultured scholar with mind both broad and deep/An honest man, the noblest work of God.” Given the circumstances, Miles could be forgiven for exaggerating—or ignoring—the truth in several of those generous statements.

As even his strongest supporters would have conceded, Bushrod Johnson was not a great general. Nor was he a great man, except perhaps in his suffering—much of it brought on by himself. Still, his patient care of his handicapped son, his diligent attention to the educational needs of his students, and most of all his habitual concern for the soldiers he commanded in the Civil War, proved Johnson to be, at heart, a fundamentally decent man, despite his occasional lapses of ethical judgment. It is worth noting that none of the men who served under him—mostly Tennesseans who seemed to care little that Johnson was Ohio-born and raised—ever felt anything but pride and affection for their old commander. In their eyes, at least, he was undefeated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments