By Allyn Vannoy

The popular image of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall (Atlantikwall) is one of massive bunkers and huge artillery pieces recessed in concrete casemates stretching the length of the Reich’s coastline. It was anything but that. Yet, while it was hardly a continuous series of defensive structures, or as formidable as Allied planners thought it to be, the Wall did give them pause when planning the assault on Fortress Europe. Three elements constituted Germany’s defenses along the Atlantic coast: fire-power, fortifications, and manpower. However, none of these could have been effective without proper leadership.

Building Up the Wall

Much of the Wall’s lethality was only added in the six months prior to the D-Day landing, due to the efforts of two men—Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Rommel.

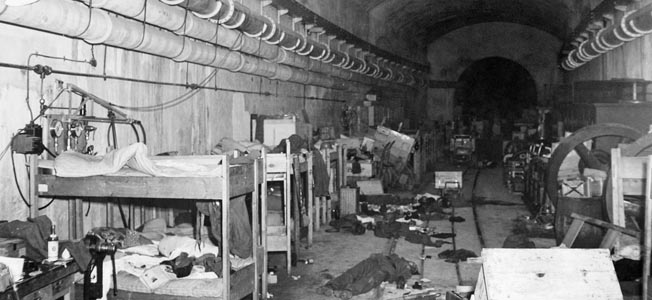

The Wall included an estimated 15,000 reinforced-concrete structures: munitions bunkers, flak bunkers, troop shelters, infantry and artillery combat bunkers, communication bunkers, depot bunkers for storing supplies and crew-served weapons, combat headquarters bunkers with staff quarters, observation and command bunkers, battery fire-control positions, and support bunkers for machinery, searchlights, and power generators.

The Germans themselves came to think of the Wall primarily as that portion on the Dutch, Belgian, and French coasts, while defenses along the Norwegian, Danish, and German North Sea coasts consisted mainly of a series of separate fortresses or heavily protected gun emplacements.

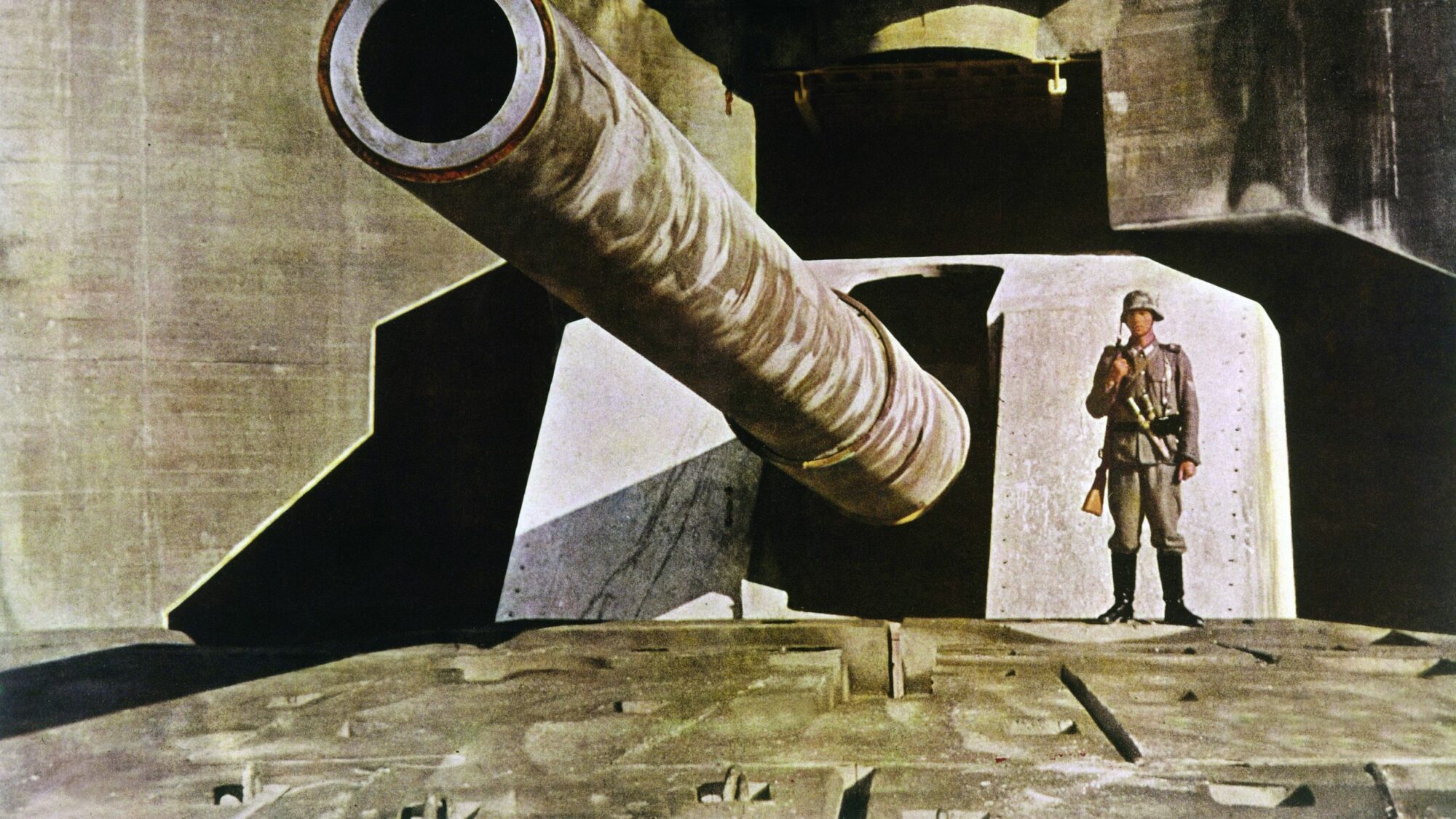

The core of the Wall was its coastal gun batteries. The number of batteries deployed by 1944 included 22 in Germany’s Helgoland Bay, with 78 guns of over 150mm; 70 batteries along the Danish coastline with 293 large caliber guns; 225 batteries in Norway with approximately 1,000 guns of 100mm or larger caliber (42 of them of 240mm or larger), and 343 batteries along the French coast, which included 1,348 guns of 150mm or larger.

Some 495 artillery casemates or other emplacements were built for heavy artillery of 150mm or larger in the area of the German Fifteenth Army, north of the Seine River; about 200 in the Seventh Army area (Normandy and Brittany); and 65 in the First Army area, along the Bay of Biscay. The batteries included over two dozen different calibers of weapons ranging from 76mm to 406mm. Many were captured French guns, but also included Russian, British, Czech, Yugoslav, and Dutch as well.

Three Phases of the Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall evolved in phases as the war took on changing circumstances for Germany. The first, or pre-Wall phase, lasted from the late summer of 1940 to December 1941, when reverses on the Eastern Front forced Hitler to alter his timetable for the war. Defensive efforts were confined mainly to protecting submarine bases and to guarding against possible British commando raids.

The second phase lasted from December 1941 to October 28, 1943, and was marked by the creation of the Atlantic Wall concept. It involved setting up a system of fortifications that would make it possible for the Wehrmacht to free up troops for tasks elsewhere—defensive installations and fire-power serving as substitutes for manpower.

The third phase began in October 1943, following Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s situation report to the Führer on the West’s defenses, and lasted until the Normandy landing in June 1944. By then, the Germans, in spite of their dwindling resources, had assembled a fairly impressive force behind a substantially improved line of coastal defenses––a system that they hoped would be sufficient to turn back an invasion.

The third element of the Atlantic Wall was the manpower or units deployed to defend it. From 1940 through 1941, Army Group D, under Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, had a small number of divisions stationed in the Netherlands, Belgium, and occupied France.

“A Propaganda Wall”

In the spring of 1942, when Field Marshal von Rundstedt took over command, the number of divisions in the area began to increase; however, many of the units were sent there primarily to rest and rebuild after suffering heavy losses on the Eastern Front.

Von Rundstedt complained that the Atlantic Wall was nothing but a gigantic bluff, a “propaganda wall.” After the war, he made a number of damning remarks about the Atlantic Wall: “The enemy probably knew more about it than we did ourselves.” He did believe that it was a formidable barrier from the Scheldt to the Seine, “but further than that—one has only to look at it for one’s self in Normandy to see what rubbish it was.”

He also described the Wall south of the Gironde toward the Spanish border as “a dreary situation” because “there was really nothing at all there.” Gloomily, he stated that, “It doesn’t suffice to build a few pillboxes. One needs defense in depth.”

Von Rundstedt was less concerned about the unfortified stretches of beach than about the number and quality of his troops to defend the wall, and the strength of his reserves. “Moreover,” he said, “the requisite forces were lacking—we couldn’t have manned them, even if fortifications had been there.”

With a few exceptions, the coastal divisions were at less than full strength and of inferior quality, made up of untrained youth, men in their late 30s or older, and others deemed unfit for frontline combat duty. They were supplemented by Volksdeutsche––ethnic Germans from across Europe––and by non-Germans recruited from the occupied territories, as well as Soviet prisoners-of-war.

Foreign troops taken into the German forces from Russia, called Osttruppen, included various ethnic groups––Cossacks, Armenians, Georgians, Ukrainians, Azerbaijanis, and Turkomans. They were formed into battalions separated by religion and ethnicity and placed under German officers, and were generally treated as second-class soldiers. By the end of 1943, there were one or two Ost battalions in almost every German coastal unit.

The coastal divisions’ weapons and equipment were also less than first rate, much of it foreign made and obsolete. There was also a severe shortage of tanks, and many units were designated “static divisions,” as they lacked even horse-drawn transport.

To make matters worse, von Rundstedt commanded only Army troops; he had no authority over the few assets of the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine in the West, or over Waffen-SS units.

Construction Begins

Preliminary work began on the Atlantic Wall in the late summer of 1940 as the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine established defenses at key ports and airfields to protect facilities for Operation Sea Lion, the planned invasion of Britain, from air raids and possible naval bombardment. The Army also brought up heavy batteries to the Pas de Calais with orders to clear mine-free paths for the planned invasion crossing and to protect the coastal area.

During September 1940, construction began on the first of three large, concrete- dome bunkers for heavy rail guns in the Pas de Calais area. These bunkers were built with armored doors and were large enough to house two 280mm guns and a locomotive.

One such bunker was situated northwest of Calais, about one kilometer from the coast. Another was sited at Vallée Heureuse, about four kilometers east of Marquise, almost halfway between Calais and Boulogne, some six kilometers from the coast. A third was placed one kilometer north of Wimereux, five kilometers north of Boulogne, near the coast. A fourth bunker, larger than the others, was built later to house a rail-gun battery not far from the first dome bunker near Calais.

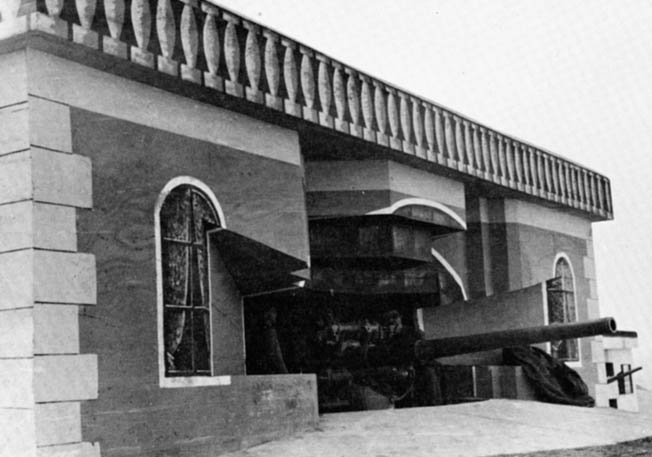

As guns were transferred from German coastal positions along the North Sea and Baltic, and from the border-guarding Westwall, the first concrete mounts were completed in November 1940. Most of these weapons were installed in huge casemates or mounted on concrete emplacements. Heavy naval guns were mounted in turrets with some placed in concrete casemates with their turrets. Defensive support or protective combat bunkers and munitions bunkers were also built to service the guns.

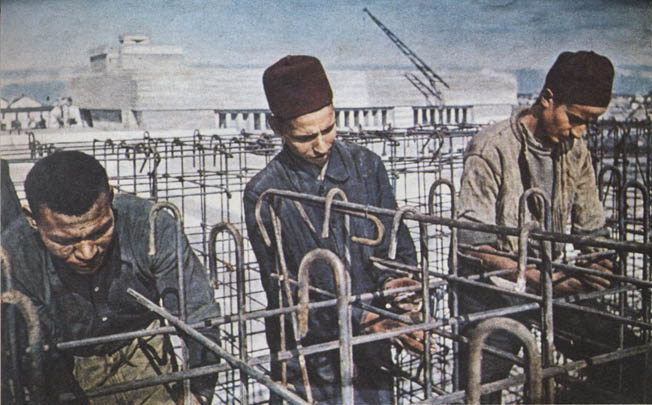

Technical work on facilities and structures was the responsibility of the Organisation Todt (OT)—a civil and military engineering group responsible for the design and construction of the prewar Autobahn system and the Westwall (Siegfried Line) along the French-German border. OT was later absorbed into the Ministry for Armaments and War Production (Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion).

Construction work along the coast in 1941 was primarily devoted to the building of coastal batteries and U-boat bases. Most of the concrete used went into submarine pens and the second largest amount to Luftwaffe airfields and installations.

On March 28, 1942, Führer Directive No. 40 called for the creation of the Atlantic Wall. Long-range coastal batteries were to be placed to protect important harbors as well as military and industrial targets in coastal areas. In addition to preventing landings, importance was also placed on safeguarding the sea entrances of protected waterways. The concern was that any interruption of coastal shipping could have serious consequences.

Stützpunkt-gruppen

Von Rundstedt, the commander of the German Army in the West––Ob West (Oberbefehlshaber West), issued orders during May 1942, based on Directive No. 40, which established the organization of the coastal defenses in a hierarchy from Festungen (fortresses) with heavy and super-heavy guns placed in reinforced concrete structures, then Verteidigungsbereiche (defense sector), followed by Stützpunkt-gruppen (strongpoint group), Stützpunkt (strongpoint), down to Widerstandnester (resistance nest, or WN).

A “strongpoint group” consisted of two or more strongpoints of either infantry or artillery types. An infantry strongpoint consisted of several infantry positions with crew-served weapons, while artillery strongpoints consisted of a battery of artillery or antiaircraft weapons.

The strongpoint included concrete works for various types of weapons, munitions storage, command posts, and troop shelters. Large strongpoints could include more specialized types of bunkers such as for medical facilities or a communications center. The strongpoints were designed for all-around defense, protected with barbed-wire obstacles and minefields. They were normally occupied by a reinforced platoon, some by company-size formations. These positions were stocked with sufficient supplies to operate for about two weeks without resupply. A strongpoint group could generally accommodate a battalion-size force and held enough stores to maintain operations for up to four weeks.

The layout and structures varied among strongpoints. One strongpoint group consisted of an infantry position with an 88mm gun casemate, a 75mm gun casemate, a 50mm antitank gun casemate, three Tobruk or Ringstände (a small open circular position, dug-in flush to the ground and camouflaged) mortar emplacements, two field positions for mortars, two machine-gun bunkers, three Tobruks for machine guns, one concrete machine-gun emplacement, and 10 field positions for machine guns. In addition to mines and barbed wire, the group included an antitank wall that barred the exit from the beach.

Another strongpoint infantry position consisted of a Renault tank turret mounted on a concrete bunker, two field positions for 75mm guns, four concrete mortar emplacements, a field position for a machine gun, another for an antiaircraft gun, and six stationary flamethrowers––all surrounded by an assortment of mines and wire barriers.

In contrast, a strongpoint artillery position included five concrete emplacements for 155mm guns, six field emplacements for 75 to 155mm guns, an observation post, two concrete mortar positions, seven Tobruks for machine guns, and a searchlight.

The Widerstandnester was the smallest defensive position. It could be found alone or as part of a defense sector or fortress. Resistance nests included infantry positions garrisoned by one or two infantry squads with enough supplies to hold out for a week. They might include at least one antitank gun, several machine gun and mortar positions, and usually a few concrete bunkers. They were set up for all-around defense with barbed-wire, minefields, and trenches.

Strengthening the Coast After Dieppe

In August 1942, the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division and British Commandos assaulted the French port of Dieppe in a large-scale raid. While the raid failed to achieve many of its objectives and suffered heavy losses, it caused Hitler to direct changes in the number of Atlantic Wall positions. He ordered the completion of 15,000 positions before the summer of 1943, but OT engineers reported that only 40 percent of this number could be achieved by the target date. By December 1942, about 5,000 structures had been completed, and by June 1943 the number would reach over 8,000.

Construction proceeded apace. By April 1943, seven times as much concrete was poured on Atlantic Wall sites as in May 1942 (780,000 versus 110,000 cubic meters), a month that had seen the amount double from March 1942 (50,000 cubic meters). But U-boat pen construction consumed 80 to 130,000 cubic meters a month during this period, despite complaints from the Army.

Each of 15 defense sectors in Western Europe were centered around key locales. In France, these included Royen, La Pallice-La Rochelle, St. Nazaire, Lorient, Brest, St. Malo, Le Havre, Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk.

Ostend served as the key defense sector in Belgium. On the Belgian coast, the area around Zeebrügge was heavily protected by several heavy batteries that included 155mm, 170mm, 203mm, and 280mm guns.

The Dutch coastal defense sectors included Vlissingen, encompassing the islands of the Scheldt Estuary, the Hook of Holland (Hoek van Holland), Ijmuiden, and Den Helder, and contained some of the Wall’s heaviest defenses. Verteidigungsbereiche Den Helder had two batteries of 120mm guns, one battery of French 194mm guns, and several 105mm guns. The next most heavily defended area was at Ijmuiden, a Festung with several batteries of naval guns ranging from 120mm to 170mm.

The old fort of Hoek van Holland contained several batteries from 120mm to 280mm. Behind the fort, to the south, was Battery Brandenburg, which had two 240mm guns in turret-mounted casemates. Battery Rozenburg, to the rear of Battery Brandenburg, had three 280mm guns from the battle cruiser Gneisenau, mounted individually in turrets on casemates. The battery’s strongpoint included a range finder mounted on a tower about 30 meters high. It also had three munitions bunkers, troop shelters, searchlight bunkers, and positions for close defense. The fortress itself included about 14 strongpoints and 40 resistance nests. Many of the strongpoints had an artillery battery and supporting positions, while most of the resistance nests consisted of from two to over a dozen bunkers. The resistance nests contained troop shelters and bunkers for close defense—casemates for machine guns and antitank guns.

Of the islands at the mouth of the Scheldt and Rhine Rivers, Walchern was the most heavily defended and included a number of medium artillery batteries as well as a couple of heavy batteries.

Gaps between defense sectors all along the line were to be covered by strongpoint groups, strongpoints, or resistance nests. The area between the mouth of the Somme and the Belgian border consisted mainly of side-by-side defense sectors.

The Atlantic Wall in France

It was France that had the longest coastline and thus the greatest number of installations. The Pas de Calais, between Dunkirk and Étaples, was one of the most heavily defended portions of the Wall and included three sectors under LXXXII Army Corps. One sector included Festung Dunkirk with several heavy batteries, over 20 strongpoints and more than 10 resistance nests.

In the sector between Dunkirk and Boulogne, there were nine positions with dome bunkers for heavy railway guns, most of which were 280mm. In addition to the guns were some of the largest super heavy artillery in the West. East of Calais was Battery Oldenburg with two 240mm guns, Bastion II with three 194mm French guns, Battery Prinz Heinrich with two 280mm guns just outside Calais, and Battery Lindemann with three 406mm guns between Calais and Cap-Blanc-Nez. The Lindemann guns were emplaced individually in turrets, protected by massive concrete casements four meters thick. By 1944, these guns had fired some 2,226 shells at Dover.

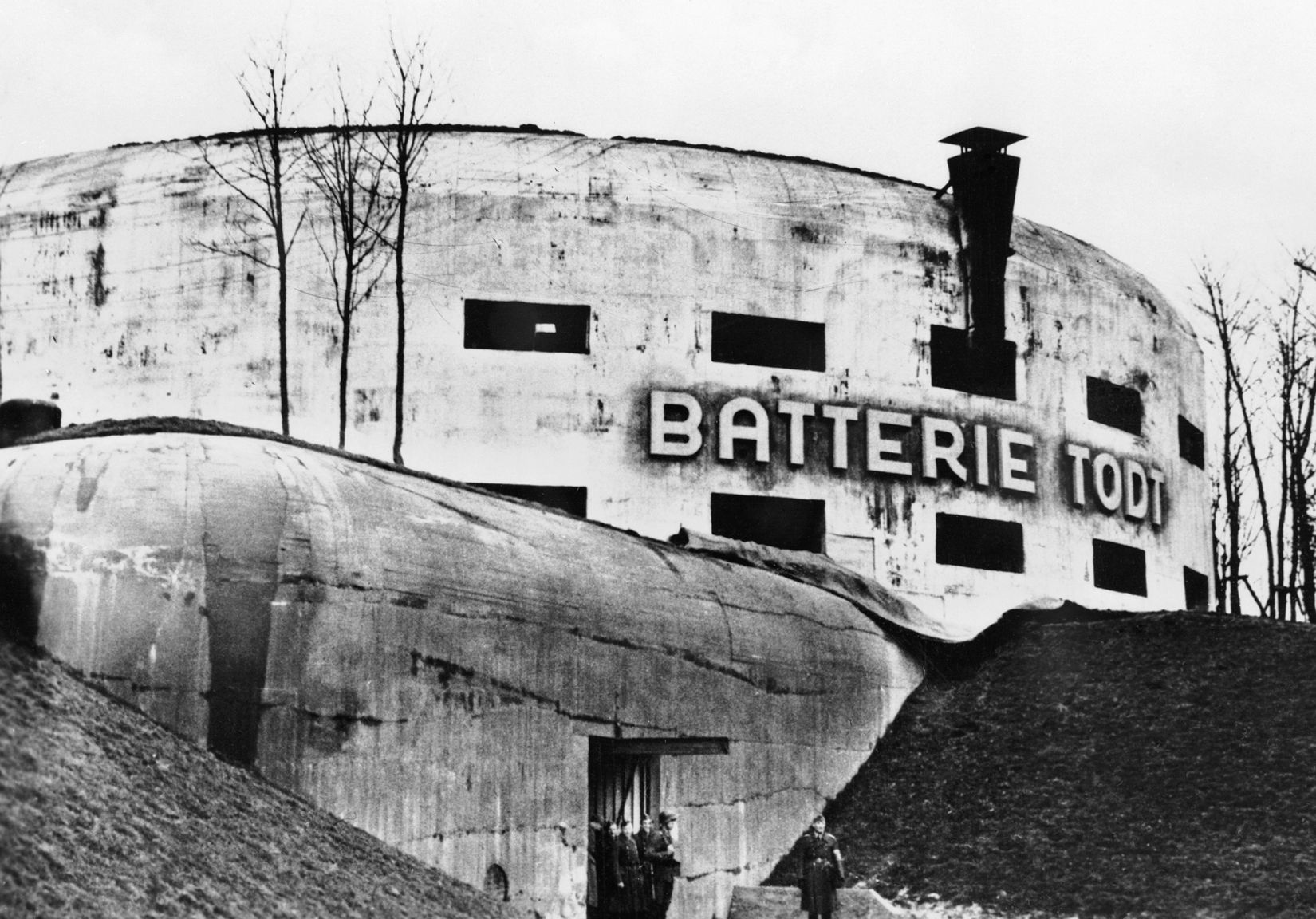

In the vicinity of Gris Nez was the massive Battery Todt with four 380mm guns and Battery Grosser Kurfürst with four 280mm guns. At Fortress Boulogne were several batteries, mostly medium, and Battery Friedrich August had three 305mm guns, over 20 strongpoints, and more than 15 resistance nests. To the north, the fortress was anchored at the coast by three strongpoints forming the La Crèche position.

Farther down the coast, in the Fifteenth Army sector, was the fortress at Le Havre. Its heaviest battery, the naval battery of La Corvée, located at Bléville, on the north side of Le Havre, was planned to consist of three 380mm guns in casemates; however, only one piece was ever mounted. The fortress did consist of many strongpoints and resistance nests, including over 20 resistance nests forming Stützpunktgruppe Nord and Ost, which covered the landward side of the fortress.

Stützpunktgruppe Ost encompassed a large flooded area with most of the area on its flanks protected by large minefields. The front of Stützpunktgruppe Nord included a very large minefield running across half its length, with an antitank ditch extending from one side of the minefield to the coast. Another antitank ditch covered a gap from the first minefield and the minefield of the Ost group. Stützpunktgruppe Süd covered most of the coastline of the fortress.

Next, at Le Tréport, were several strongpoints that included two batteries of three 170mm guns each, as well as radar for detecting ships and for fire control of the batteries.

Farther west, Battery St. Marcouf, with Czech 210mm guns at Crisbecq, protected the east side of the Cotentin Peninsula.

Another fortress was built around Cherbourg, one of the largest ports in France. Its batteries included guns ranging in size from 105mm to 240mm. The city’s vintage forts on the mole were integrated into the German defenses. Old forts surrounding the city were used to form an inner defense belt. Fort Roule, on a large hill overlooking the city, was heavily defended and below it was a battery of 105mm guns in casemates built into the hill. It wasn’t until 1944 that the Germans began to work on defenses on the landward side—on the outer belt—which was to serve as the primary defense line. This belt followed the crest of the surrounding heights; however, only a scattering of positions were completed.

The west side of the Cotentin Peninsula was protected by the Channel Islands—Guernsey, Jersey, and Alderney, which the Germans had taken from the British in 1940. On Guernsey was the heavy Battery Mirus with four 305mm guns, and a few batteries with 210mm and 220mm guns. Jersey also had 210mm howitzer batteries and a 220mm gun battery, while Alderney’s heaviest battery was one of 170mm naval guns. By the summer of 1944, over 300 bunkers for artillery, observation, fire control, munitions, machine guns, and a tunnel system were built on the islands. Several kilometers of concrete antitank walls and old granite seawalls protected the beaches.

The next group of heavy defenses began in Brittany near St. Malo. St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were heavily defended fortresses. Brest, where the Germans used the old fortifications and added numerous strongpoints and resistance nests, was probably one of the most heavily protected fortresses in France. Lorient, one of the most important U-boats bases on the Atlantic, was also heavily fortified. The mouth of the Loire was covered by a number of artillery batteries, and at St. Nazaire a huge naval fortress occupied both sides of the river to guard against naval incursions against the submarine pens and the world’s largest drydock.

The remainder of the French Atlantic coast, under the First Army, included fortifications at La Pallice-La Rochelle. A Verteidigungsbereich was built that included not only the area around the city and port, but also the islands of Ré and Oleron. Few of the batteries along the First Army coast were heavier than 155mm. The most heavily fortified point was the mouth of the Gironde, which had a fortress on each side to protect the port of Bordeaux.

On paper, the Atlantic Wall looked more than formidable––it looked impregnable. If both the Germans and the Allies believed it to be so, it is not hard to image why.

Development of the Atlantic Wall Hindered

German building programs slowed during the second half of 1943. Part of the reason was due to the shifting of OT laborers to other projects, including repairs to bombed dams in the Ruhr and the construction of a bauxite mine in southern France.

Development of the Wall was also affected as OT favored focusing on building single, large defense projects because it did not have enough motor vehicles to move men and equipment from place to place. This lack of vehicles also made OT officials reluctant to undertake projects away from major supply centers and railheads. The Army did not have direct control over OT, so Army planners could only suggest projects.

Construction was also impacted by interservice frictions between the Army and Navy over the positioning and command of the coastal artillery batteries during 1941 and early 1942. Directive No. 40 provided clarification in that Ob West was to select a commander for each coastal sector. In most instances, this meant that a local Army division commander was put in charge, but in certain areas, especially at naval strongpoints, Kriegsmarine officers assumed control.

Von Rundstedt’s Assessment of the Atlantic Wall

During 1943, Ob West ordered the creation of positions up to 15 kilometers behind the coastal defenses. Existing defenses extended no more than three to five kilometers in depth, even in the most heavily defended sectors. Von Rundstedt disagreed with Hitler, who expected the enemy to be destroyed at the landing site either by defeating him before he achieved a foothold or, failing that, by launching an immediate counterattack. The field marshal did not believe that the initial invasion would be smashed on the beaches and felt that mobile reserve forces should be able to concentrate and defeat the enemy after he moved inland.

To effect this, von Rundstedt wanted to create secondary positions, which would consist mainly of support points and strongpoints that could be used to contain the enemy and allow time for an effective counteroffensive. However, insufficient manpower was assigned to the building of these secondary positions and so construction proceeded very slowly.

One of the keys that impacted the Atlantikwall’s development was von Rundstedt’s situation report to the German Armed Forces High Command (OKW) of October 28, 1943––a critical report that cited a number of shortcomings of the Wall and the Reich’s defenses in the West.

Von Rundstedt’s report evaluated how the Wehrmacht might best make use of its defenses when faced with an enemy who possessed both naval and air superiority. Even though permanent fortifications—built out of concrete and well constructed, camouflaged, and field-type installations—were essential for the impeding battle, von Rundstedt warned that the German High Command should not be deluded into thinking that these obstacles made the Atlantic Wall impregnable. He felt that by making his forces more mobile he could minimize the probably of an Allied success in the West. The report also emphasized the need for more and better equipped personnel.

In terms of numbers, von Rundstedt declared that the strength of the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe formations was clearly insufficient to counter growing Allied air and sea superiority. Furthermore, naval and air force artillery units, whose crews were working in close conjunction with the Army, lacked sufficient ammunition and equipment.

He asserted that the Army units available were weak and needed to be revitalized, and that there was too much area to cover with the forces available. By October 1942, 22 infantry divisions had been deployed along the coast. All these units had been well equipped and most of them had three full-trained regiments and a full complement of 36 artillery pieces. In reserve were seven panzer and motorized divisions of excellent quality, plus six more infantry divisions.

In October 1943, although 27 divisions were now stationed along the Atlantic coast, plus 400 miles of French Mediterranean coastline, many of the formations were much too weak in artillery and consisted of only two inexperienced and largely immobile infantry regiments. Of the reserve forces, all six panzer and motorized divisions were still in the process of being formed or were being refitted after service on the Russian Front. The seven infantry units in the interior consisted of only two reserve divisions of marginal value, two divisions forming, and three reinforced regiments.

Von Rundstedt concluded his report by stating that the divisions manning the coast had to be strengthened to the normal complement of three regiments, sufficient antitank weapons needed to be provided, adequate supply personnel had to be added, and, finally, substantial portions of these divisions needed more vehicles to be made mobile.

The Coast as Main Line of Resistance

On November 3, 1943, a week after von Rundstedt’s report was submitted, Hitler issued Directive No. 51, which resulted in a flurry of activity among German planners during the last two months of 1943. Ob West made plans for making the coastal divisions mobile, as well as for upgrading the panzer formations in the theater.

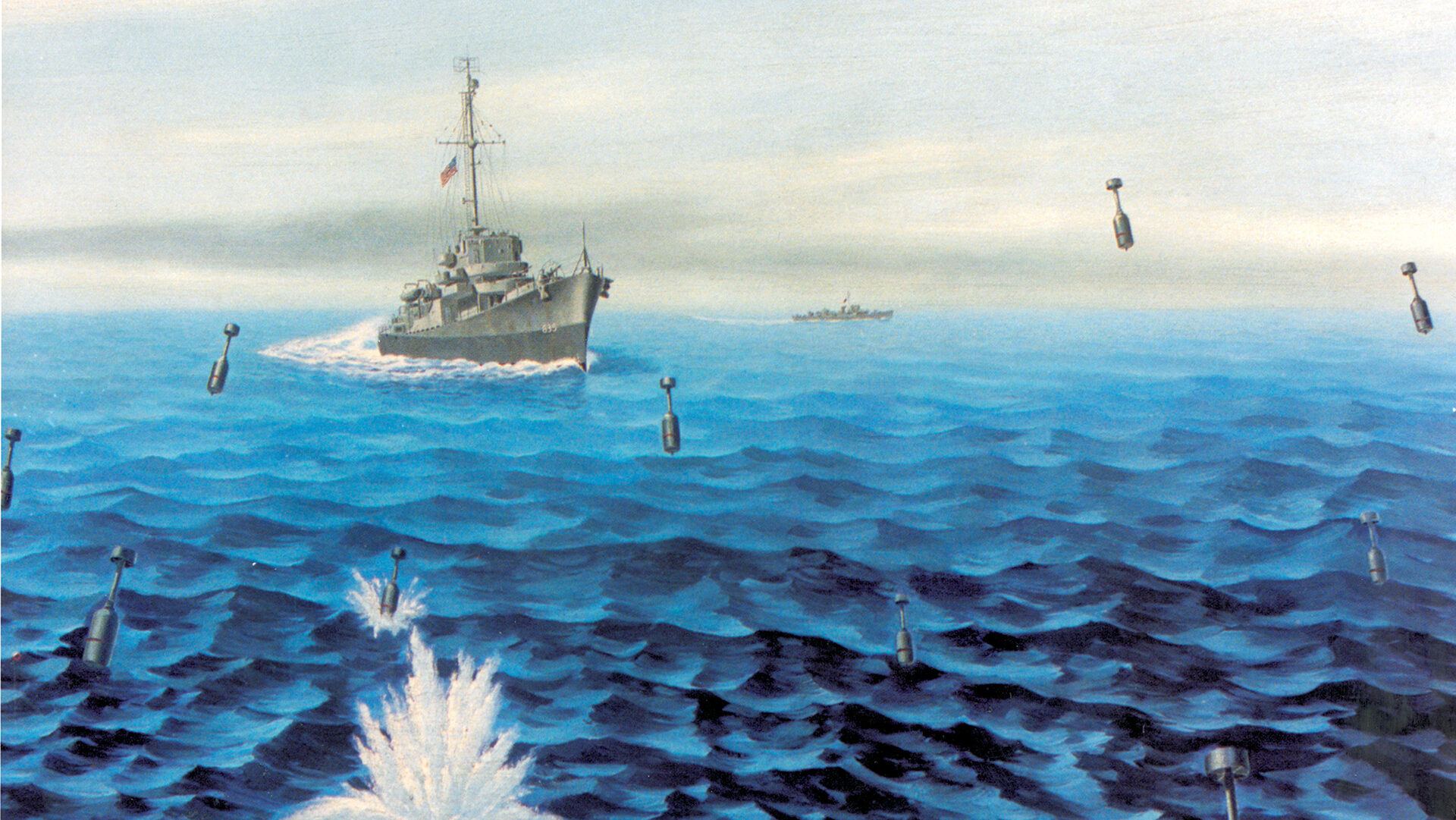

Also set forth was an ambitious building program for 1944 that included the erection and improvement of numerous permanent and field-type fortifications. The Kriegsmarine also took steps to add more ships, mines, and artillery pieces to its defensive arsenal.

Following an inspection tour of German coastal defenses as directed by the Führer, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was assigned to command Army Group B, subordinate to Ob West, covering the French, Belgian, and Dutch coastlines, and work on the Atlantic Wall took a new direction and greater urgency. The gaps between the defense zones were to be closed. By this time, major construction work on large concrete structures, such as submarine pens, had almost come to an end, but the amount of labor from the OT and RAD (Reichsarbeitdienst––the National Labor Service) and the availability of construction materials was severely curtailed.

Damage caused by the Allied bombing campaign in 1944 had increased the demand for labor and material at home for repairs and maintenance of infrastructure, leaving little for the West. Allied air attacks against transportation lines and communications centers also prevented the few available resources from reaching the West in a timely manner. Much of the concrete available was also earmarked for the construction of V-weapons’ launching sites. Despite this, Rommel was able to push construction to highs not seen since mid-1943.

To Rommel, the main line of resistance had to be the coast. The invading enemy was to be engaged in force on or near the coastline and prevented from establishing a beachhead. To accomplish this, Rommel advocated a number of measures, including extensive use of naval and land mines, beach obstacles, as well as continuing to strengthen strongpoints. Also, Panzer divisions were to be placed as far forward as possible so that they could launch an immediate counterattack against any major Allied assault.

Rommel and von Rundstedt realized that if the Atlantic Wall were to have any chance of success they would have to do more than just strengthen the existing coastal fortifications––they would need a substantial upgrade in the number and quality of personnel and weapons. Any one of these undertakings presented a formidable task at this stage of the war.

Despite this, they managed to realize considerable progress during the first five months of 1944, and the improvements would have been greater had there not been the demands of other high-priority projects and a series of crises in other theaters.

Over 4,600 New Fortifications

The buildup was most noticeable in terms of coastal fortifications. One plan consisted of improving the existing permanent defenses. A second program was to construct a system of secondary defenses some 15 to 25 miles inland from the coast. And a third program––the one with which Rommel became most closely associated––called for a substantial increase in the number of field fortifications being placed on or near the beaches, thus making the Wall a comprehensive system of fortifications.

In terms of permanent fortifications, the Germans continued to concentrate a substantial portion of their heavy construction work near the major ports. Hitler went so far as to declare 11 of the ports “Fortresses” (Festungen) on January 19, 1944.

Singled out were Ijmuiden and the Hook of Holland in the Netherlands; Dunkirk, Boulogne, and Le Havre in the Fifteenth Army sector along the Channel; Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, Lorient, and St. Nazaire in the Seventh Army area; and the Gironde River estuary that led to Bordeaux in the First Army area.

During February and March, OKW added three more—the Channel Islands and the harbors of Calais and La Pallice-La Rochelle. Designation as a Festung was rather hollow since most of them had already been declared defense areas in 1942, and had therefore already been given considerable attention.

Inside both the fortresses and the coastal strongpoints, engineering troops and OT workers proceeded to improve the heavy infantry weapon positions, the command posts, and even machine-gun nests as well as many of the coastal artillery batteries that were exposed. OT also began moving artillery pieces to make the guns less susceptible to Allied air and ship bombardments, and worked to camouflage existing batteries and construct dummy positions.

Local commanders lent a hand by reducing the number of hours that troops spent in combat training and had them assist in construction efforts. The soldiers worked to improve strongpoints using sea walls, ship canals, and old ramparts—filling in the gaps between with field defenses, preparing real and bogus minefields, setting up barbed-wire entanglements, and digging antitank ditches.

By effectively utilizing the men and materiel at their disposal, the Germans made considerable strides in building up defenses prior to the Allies’ D-Day. During the first four months of 1944, the number of cubic meters of concrete laid by OT doubled from 357,000 to 722,100 per month. From 1941 to the end of 1943, the Germans had erected some 8,478 concrete structures along the Channel and Atlantic coasts, but from January to May 1944, over 4,600 hardened fortifications were erected, including those on the French Mediterranean coast.

Rommel’s Beachhead Obstacles

Rommel also introduced his own ideas about beach obstacles, which were to be covered by light and medium guns and machine guns in order to turn every foot of shoreline into a killing ground. He placed a premium on laying minefields and beach obstacles based on the impressions that had been made on him by the British defensive positions along the Gazala Line in Libya in 1942.

Rommel promoted a program that stressed the use of field hindrances, which von Rundstedt supported, and included a variety of measures to disrupt an Allied landing, such as laying large numbers of land mines, flooding low-lying areas, and placing foreshore obstacles and tall stakes called “Rommel asparagus” just behind the coast.

The latter were simple antiairborne and antiglider devices made from a pointed pole driven into the ground and spaced so that the flat, open terrain was turned into a field of deadly wooden spears.

Rommel’s most important upgrade of the Wall’s defenses was the use of foreshore obstacles. Placed along the beaches, these obstacles were designed to fill the gaps between strongpoints, protect the more remote beaches, and delay an Allied landing, even if only for a short time.

Rommel ordered underwater obstacles planted in three to six rows along the beaches to disrupt an amphibious operation, whether at high or low tide.

The obstacles consisted of various devices. The simplest was an 8- to 10-foot wooden stake or concrete pole driven into the beach sand and angled toward the sea. Some of the stakes had mines or grenades attached, and all of them, when submerged, could rip open the hull of a landing craft.

The same was true of numerous V-shaped ramp-like structures, which the Germans sloped toward the sea and armed with mines or artillery shells designed to explode on contact.

A third type of obstacle was the concrete tetrahedron. This pyramid-shaped object was six feet high, weighed nearly a ton, and could also be mined to sink a landing craft.

Another hindrance was the “hedgehog” tank obstacle. It was made of three seven-foot steel girders welded together in the middle so that the beams presented three points angled 120 degrees apart.

Finally, there were Belgian gates––heavy steel antitank structures resembling gates, about nine feet high, and nine feet across, a few with waterproof mines attached..

A tremendous amount of progress had been made. From 1941 to October 30, 1943, the Germans had laid 1,992,895 mines in the West; by May 30, 1944, the number had increased to 6,508,330. Yet, this figure fell far short of Rommel’s estimated need of 50 million.

By mid-May 1944, there were 517,000 foreshore obstacles on the Channel beaches, 31,000 of them fitted with mines. Farther out to sea were a variety of shallow-sea naval mines.

But, at the beginning of June, only three of the six rows of obstacles Rommel wanted had been placed along the Normandy beaches. This lack was due in part to a shortage of material in April.

Increase in Personnel on the Atlantic Wall

Yet, during the first half of 1944, there was a steady rise in personnel. On October 4, 1943, Ob West listed 38 divisions ready for combat and 13 additional divisions in the process of forming. The number of ready divisions toward the end of December increased to 41, with seven more being formed or refitted. By April 1944, the total figure had climbed to 54 divisions and would reach 58 just before D-Day.

Forty-six of the 58 divisions were positioned along the coast. The Fifteenth Army had 18; the Seventh Army had 14; First Army, on the Bay of Biscay, had four; the Nineteenth Army, on the French Mediterranean coast, had seven; and there were three in the Netherlands; two reserve divisions were located in the interior of France.

The remaining 10 divisions were armored formations. Three panzer divisions were stationed north of the Seine, three between the Seine and Loire Rivers, and the other four in the south of France.

These forces possessed 3,300 artillery pieces, 1,343 tanks, and 1,873,000 troops. Complementing the ground forces were five Navy destroyers in the Bay of Biscay, four torpedo boats, 29 motor torpedo boats, and 500 small patrol boats and minesweepers. Thirty-five small submarines were located at Brest and other Atlantic harbors. The Luftwaffe’s Third Air Fleet had 919 aircraft, of which 510 were operational as of late May.

The Atlantic Wall Breached

But the chances of Rommel or von Rundstedt beefing up the Atlantic Wall defenses even more was at an end. On the cold, gray dawn of June 6, 1944, time had run out.

The Atlantic Wall achieved at least a partial success. Almost from the Wall’s inception, the Wehrmacht regarded the Allied capture of an important harbor as a necessary prerequisite for sustaining an invasion front so, by June 1944, the Germans had transformed the harbors into fortresses. Cut off and dependent on their own resources, many of these beleaguered German garrisons held on tenaciously before finally surrendering. These actions helped to produce a logistics crisis for the Allies during the late summer and fall of 1944.

Though the Wall was weak in many places, there were enough artillery pieces distributed in key locations to possibly impede an invasion. All the major ports were defended to some degree against an attack from the sea and most were prepared with all-around defense. None of the large or medium-size ports were so vulnerable that an invasion force could capture them easily.

Beside causing logistics problems after the landing, the Wall dissuaded the Anglo-Americans from directly attacking the Pas de Calais and convinced them not to undertake a cross-Channel invasion until 1944. Given just a bit more time and a few more resources, it could have been much worse for the Allies.

Yet, in spite of all the money, manpower, and effort expended, in the end, thanks to information provided by British intelligence and the French Underground, a bit of luck, and many determined soldiers, the Allies breached the “impregnable” Atlantic Wall in a matter of hours on June 6, 1944.

They found its weaknesses, exploited them to drive wedges into the openings, and then rapidly forged their beachheads.

Dear Allyn

I, an english living here in Holland have an interest in the construction and indeed demolitions of the AW here. I just wondered if any references might spring to mind defining the types of bunkers. I understand there to be as many as 2k defined designs, each with required material quantities, design, manpower requirements etc.

Thanks if you can help.

Best Robin

I can help

Hugs from vrazil !

Best Robin,

Check out “Fortress Third Reich” by J.E. Kaufmann and H.W. Kaufmann.

AL

Great description of the Atlantic wall. It’s a good thing that the Germans did not do more.

One event that was of great help to the Allies was Hitler’s refusal to allow Rommel to make decisions on troop movement responses to the invasion until too late to be of use. Hitler firmly believed until more than 24 hours after allied landings, that the primary landing point would be Calais. This gave the Allies time to consolidate the beach head and ready a move toward the interior.

20 years ago I visited Normandy on a staff ride while stationed in Europe. The Atlantic Wall fortifications were quite impressive even as ruins. In several places I read that the Germans for several weeks thought that Normandy was just a diversion or a secondary operation. They kept significant forces deployed near the Pas de Calais thinking the main attack was going to come there. They realized too late the actual significance of Normandy.