By Mark Simner

“Your heart stops. You feel dizzy and sick. You think you’re going to piss yourself and then you feel the pain. Something hit me in the spine and I knew it was a rifle butt. I weighed about seven stone [98 pounds] by this time and my bones were jutting just below my skin. Then there was a second thud as my legs gave way, a rifle butt to my head.”

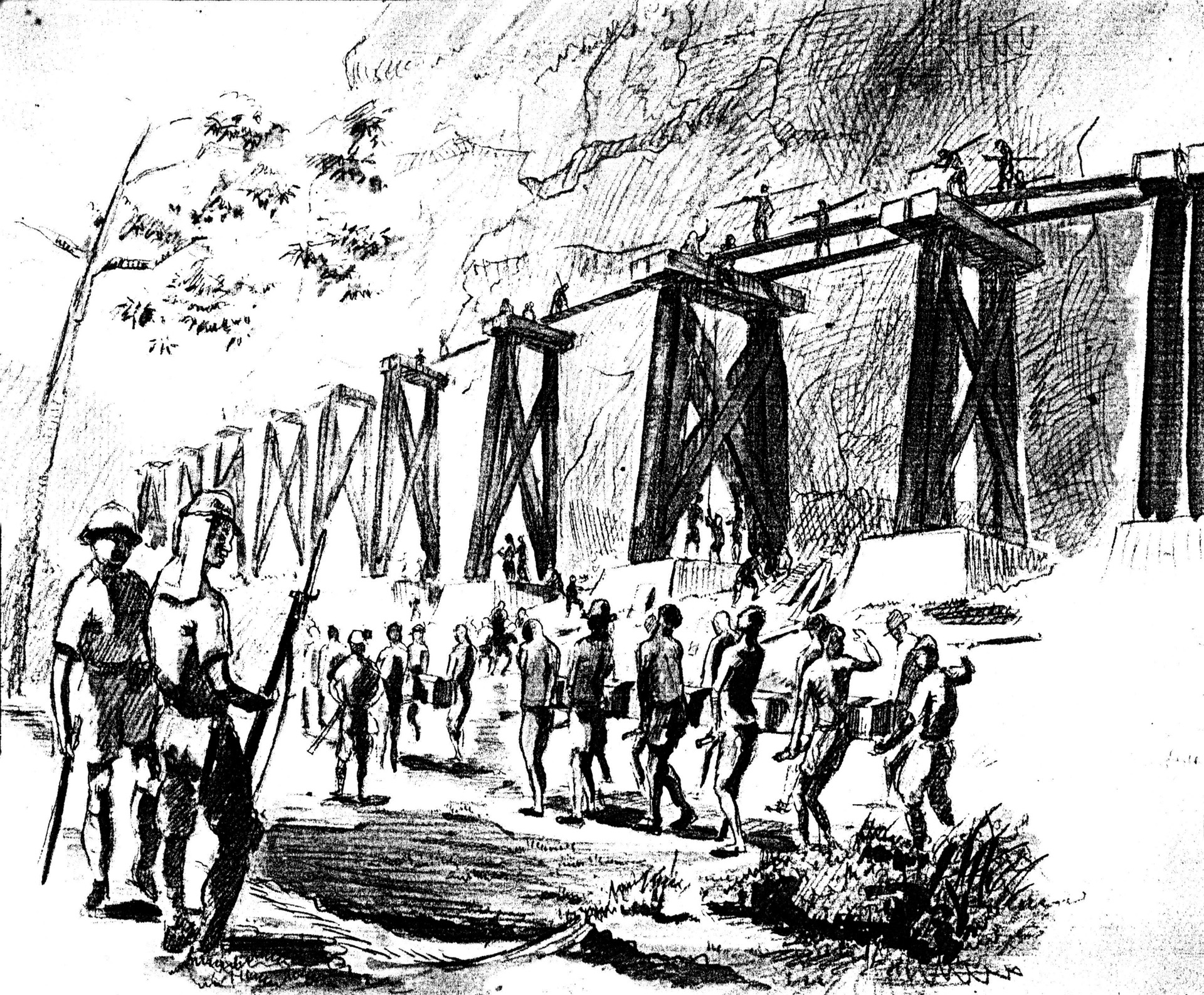

So said Private Reginald Twigg, Leicestershire Regiment—one of thousands of British prisoners of war who were forced to build a railroad bridge through the dense Thai-Burmese jungle.

Captain Reginald Burton, Norfolk Regiment, recalled, “Tears streamed down my face as the Jap sentry came up to me, his face contorted with rage. After barking incomprehensible orders, he kicked me, then beat me with a bamboo cane until I was semi-conscious. I honestly thought he was going to kill me, but eventually he left after giving me a few farewell kicks in the groin. This resulted in permanent injury, which I have to this day, to my scrotum and testicles.”

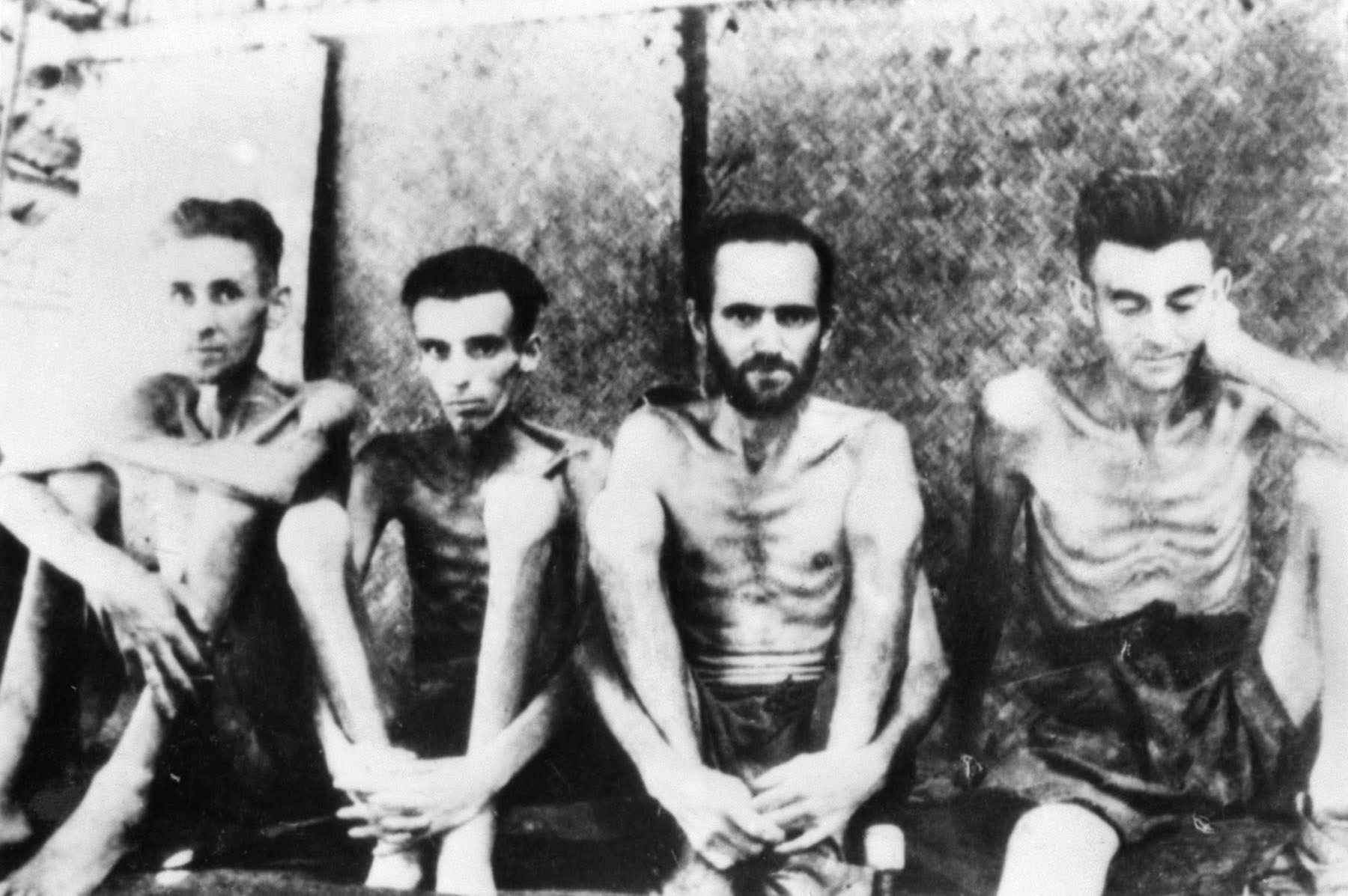

These are the horrifying words of two British soldiers held prisoner by the Japanese during World War II and forced to work on the infamous Thai-Burma “Death Railway.” Although their words can only hint at the brutality and abuse they endured while in captivity, they were, in fact, in some ways lucky. They survived the tortures of their captors, the back-breaking work constructing the railway on a minimum of rations, and the dangerous conditions of the equally savage and inhospitable jungle.

Many others were not so fortunate, dying of starvation, disease, or arbitrary execution. In total, more than 12,000 Allied prisoners of war died constructing the railway, along with tens of thousands of Asian civilian laborers known as romusha.

But why did the Japanese construct this railway of death, and what was it really like for those forced to build it?

The Japanese Invasion of Burma

Spurred on by their incredible success during the 1941 Malaysian campaign, the Japanese soon turned their attention to Burma. Under British rule, Burma possessed a number of valuable natural resources, including oil and minerals, which Japan hoped to exploit. Seizing Burma would also help guard against potential Allied interference with their planned attack on Singapore, which eventually fell to the Japanese in mid-February 1942.

In addition, the occupation of Burma would sever the recently constructed Burma Road—a route that acted as a vital Allied supply link to Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist forces. The capture of Burma, therefore, was of great importance to Japanese strategy in Southeast Asia.

British forces in Burma at this time were painfully weak, with only the 17th Indian Infantry and 1st Burma Divisions available to oppose the inevitable Japanese onslaught. In command of these forces was Lt. Gen. Thomas Hutton, who was acutely aware of how vulnerable the city of Rangoon, then capital of the country, was. It would not be long before it became apparent how impossible his task of defending Burma would be.

On December 14, 1941, leading elements of the Japanese invasion force crossed the Kra Isthmus from Chumphon in Thailand, quickly capturing the southern town of Victoria Point and a nearby airfield two days later. Other Japanese units then pushed on along the coast, driving through Tenasserim and Tavoy on January 9.

The following day the Japanese 55th Division commenced its westerly move from Raheng in Thailand, crossed the border, and on the 22nd pushed back the British 16th Indian Infantry Brigade at Kawkareik.

By the 30th, the Japanese had reached Moulmein, quickly dislodging the 2nd Burma Infantry Brigade, which was desperately attempting to defend the city in the face of overwhelming odds.

Japanese forces would clash with the British 17th Division, under the command of Brig. Gen. Sir John Smyth, VC, at the Battle of Bilin River on February 14-18, which resulted in heavy losses for the British, who again were forced to withdraw some 20 miles under constant pressure from the Japanese both on land and from the air.

Although the British rear guard managed to keep the Japanese 33rd Division at bay, the British were increasingly being outflanked by their determined adversary, and a frantic race toward the Sittang River Bridge commenced.

Reaching the bridge, Smyth immediately ordered his division across, while three battalions of Gurkhas were instructed to hold off the Japanese. On the 23rd, mistakenly believing the Gurkhas had been encircled, Smyth issued orders for the bridge to be blown, stranding the three embattled battalions on the wrong side of the river. Many survivors of the rear guard, however, did manage to swim across the river, although they were forced to leave behind most of their equipment and the wounded, who were mercilessly finished off by the Japanese at the points of bayonets.

Despite the arrival of the 7th Armoured Brigade as reinforcements, the situation for the British in Burma was by now incredibly desperate, and when General Sir Harold Alexander arrived in Rangoon he made the sensible decision to evacuate the city.

As the withdrawal of all British forces and civilians got underway, orders were also issued to destroy the numerous oil installations, docks, and factories to deny their use by the Japanese. By March 7, Rangoon was seen to be on fire as the last British units departed.

Nevertheless, the Japanese pursued the British, again clashing with the 17th Division, which was now under the command of Lt. Gen. William Slim. However, their advance began to slow in the face of stubborn British resistance, and at Toungoo they ran into the Chinese 200th Division, slowing them even further.

Eventually, however, the Japanese began to push the Chinese back, so Slim ordered his 17th Division to mount a counterattack. Although the British enjoyed some initial success, they once again became outflanked and had little choice but to withdraw toward Prome (today Pyay) on the Irawaddy River, about 210 miles northwest of Rangoon (today Yangon).

The British and Chinese continued to resist the Japanese advance, but eventually the order was given for a complete withdrawal to India. Again, the Japanese pursued the British, but thanks to a heavy monsoon on May 12, they stopped, leaving the British to retreat soaked to the skin in thick mud.

Fearing their enemy would soon be hot on their heels, when the British reached Chittagong they adopted a “scorched earth” policy to again deny the Japanese any material help. As it turned out, the Japanese ended their advance short of the Indian border, and such a desperate course of action proved unnecessary. Burma was now completely in Japanese hands, and it had cost the British a sobering 1,499 men killed and 11,964 wounded.

Constructing the Railway

Although the British had been driven out of Burma, the fighting continued with the Allies conducting several operations against the Japanese in 1942 and 1943. These included a small-scale offensive into Arakan, but following a number of attacks the British conceded defeat after again suffering heavy casualties.

Undeterred, a second offensive was carried out by Brig. Gen. Orde Wingate, employing the now-revered Chindits, who operated deep behind Japanese lines. Yet again, the British suffered appalling casualties, and the operation, perhaps, had more propaganda than military value.

Nevertheless, the tide eventually turned against the Japanese as Allied forces grew in strength and slowly began to achieve air superiority. However, the biggest problem faced by the Japanese was their lines of supply, with almost all the war material and reinforcements they needed in Burma being brought up via the sea routes around the Malay Peninsula.

This fact was not lost on the Allies, who dispatched submarines to prey on Japanese shipping. Following the Battles of the Coral Sea (May 4-8, 1942) and Midway (June 3-6, 1942), Tokyo could no longer protect nor rely upon the sea lanes between Japan and Burma.

Profoundly aware that their lines of supply were vulnerable, which in turn would make their occupation of Burma in the face of persistent Allied pressure equally vulnerable, an alternative route was quickly needed. This alternative would be an overland railway.

The notion of such a railway was not new, the British having considered it in the late Victorian period. However, the considerable problems of traversing thick jungle terrain had rendered the project as unfeasible and too expensive. Yet this did not deter the Japanese who, as early as mid-June 1942, commenced construction on the line. Unlike the Victorian British, they had no reservations about employing forced labor to do the majority of the dangerous and dirty work.

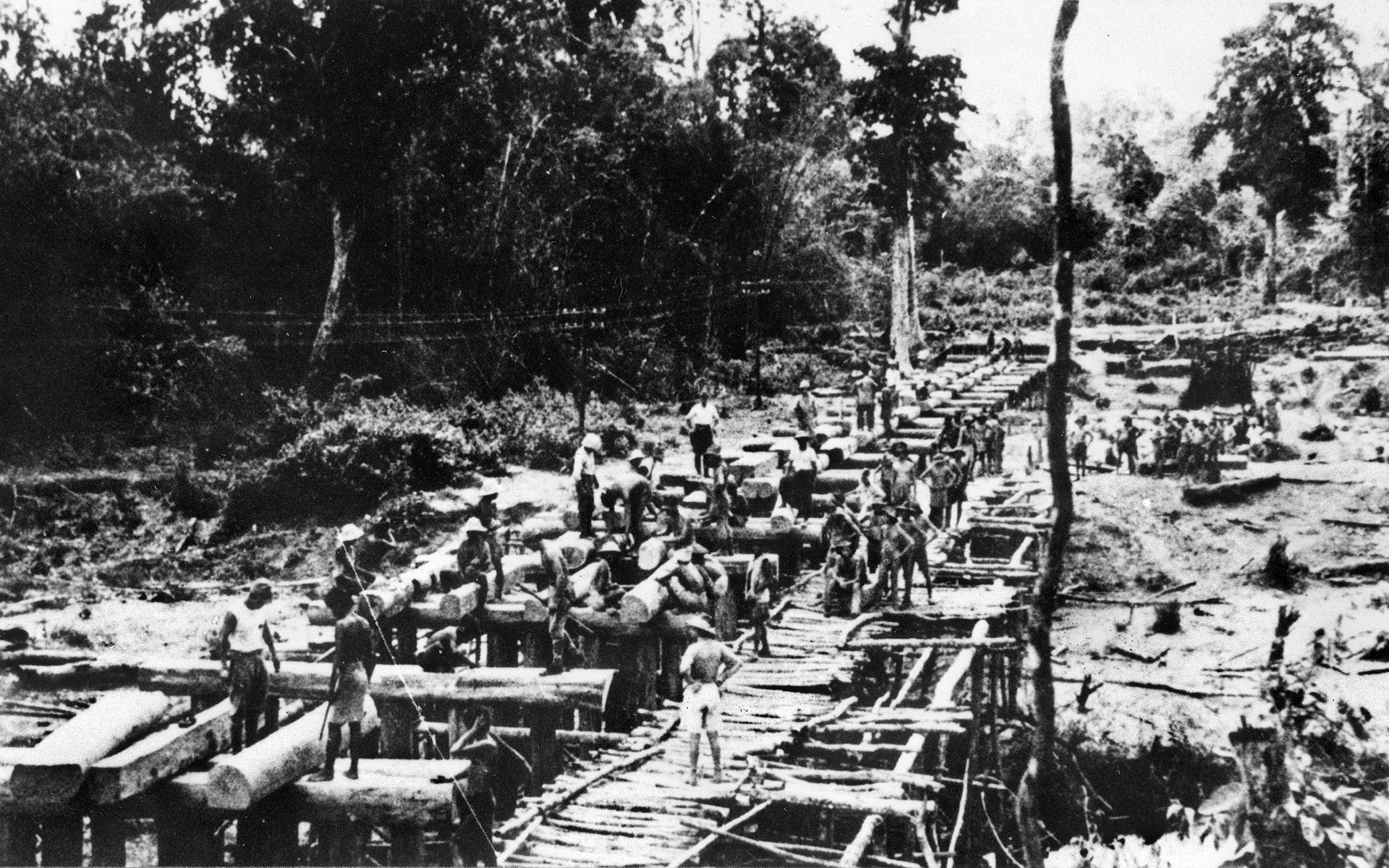

Once built, the railway would form a connection from Ban Pong in Thailand, some 45 miles west of Bangkok, to Thanbyuzayat in Burma, approximately 35 miles south of Mawlamyine, the line crossing the border between the two countries at a point known as Three Pagodas Pass. In total, about 258 miles of track had to be laid to connect the two.

Approximately 189 miles of the line would, in fact, be built in Thailand, and the remaining 69 miles were in Burma. Along the route there would be over 60 stations located at varying intervals as well as a number of bridges.

Perhaps the most infamous of these bridges was the so-called “Bridge on the River Kwai,” but others included those built over the Songkalia, Mekaza, Zamithi, Apalong, and Anakui Rivers. Most were constructed of wood while others were of iron or concrete.

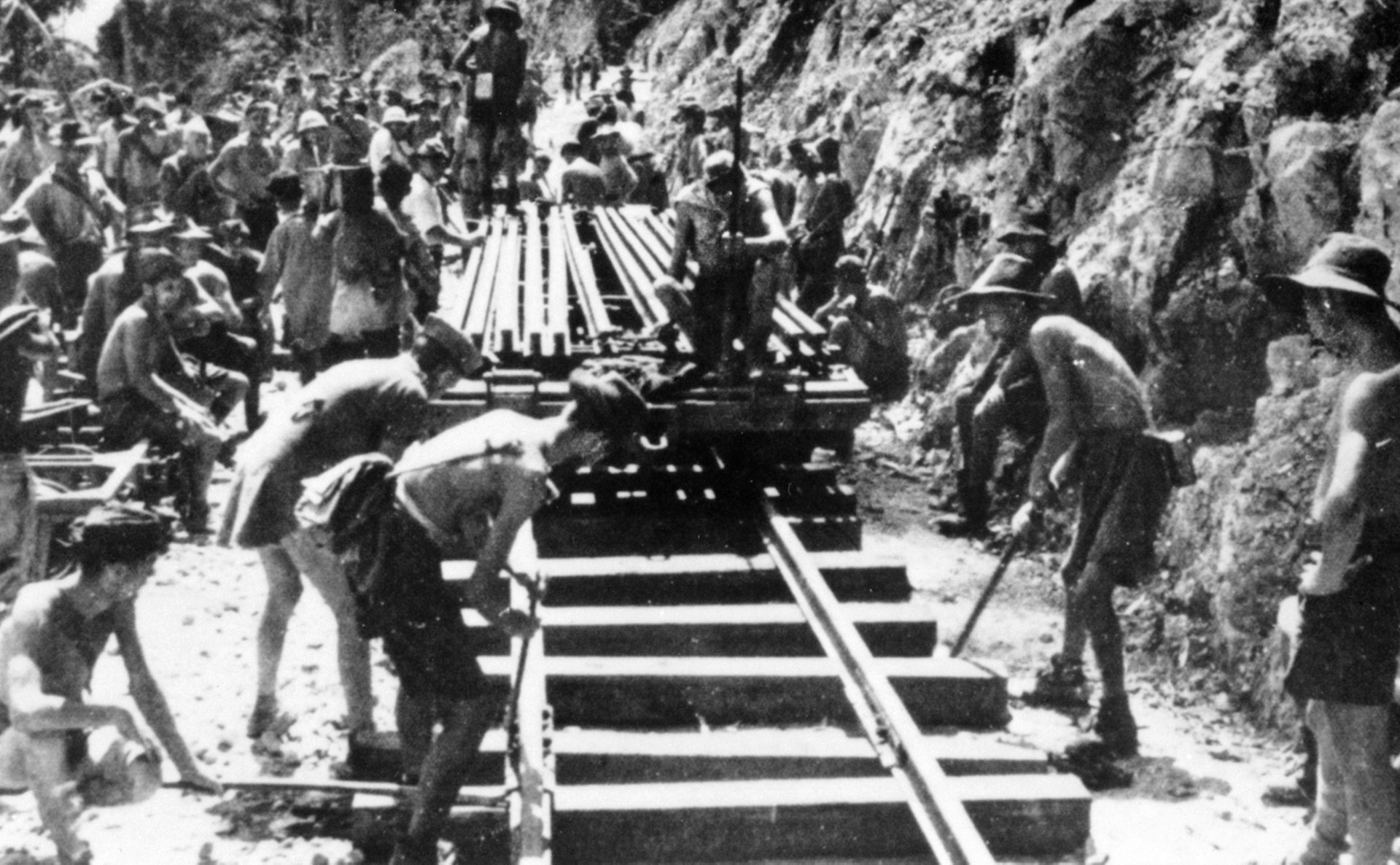

The physical construction of the railway was extremely arduous and deadly. The route passed through long stretches of mosquito-infested jungle, and frequent monsoons greatly hampered the work. The terrain was often uneven and, in addition to the construction of bridges across rivers and canyons, large sections of mountains had to be cut through in order to lay the narrow-gage track on level ground.

Recalling his work building the Burma Railway, John Swan, a British prisoner, said, “We were given a basket between two men, and two handles. We were in a chain gang and carrying soil and depositing it to make a base for the railway lines. Food was rice three times a day, and vegetable so-called ‘stew’ in the evenings, after a hot day in the sun.

“The Bridge on the River Kwai was built by sheer brute force. Trees were sawn at the bottom or dug out, and a rope was attached to the tree top and pulled down by sheer weight of numbers. In fact, one tree prodded a school friend, Ernie Outlaw, and he was blinded in one eye. Then the trees were shaped for a bridge and knocked into the ground by again pulling on a rope with a sort of weight on the top.”

The Bridge on the “River Kwai”

Formally known as Bridge 277, the Bridge on the River Kwai was later made immortal by the 1957 movie of the same name. Interestingly, the bridge was not technically built on a river called Kwai, but rather it was built over a stretch of river called Mae Klong. However, following the release of the movie, tourists came flocking to Thailand in search of what they only knew to be “the Bridge on the River Kwai.”

And so in 1960, the nearby town of Kanchanaburi changed the name of the Mae Klong River in the vicinity of the bridge to Kwae Yai. Today it remains a major tourist attraction, but for those who built it the bridge is a symbol of pain, suffering, and death.

Most of the other bridges built along the Burma Railway route were made of wood, but the actual Kwai bridge was constructed using 11 curved steel spans supported on concrete pillars, the materials being mainly sourced from Java. The movie bridge is built of logs.

During its construction, a wooden bridge was also built about 328 feet further downstream which, although made of wood and only able to carry lighter loads, facilitated the transportation of materials across the river on trucks for use in building the main railway bridge.

To service the Allied prisoners of war forced to construct the bridge, a camp was built at nearby Tha Markam. Alistair Urquhart of the Gordon Highlanders recalled, “The bridge stood encased in a great bamboo cage of scaffolding and hundreds of prisoners teemed all over it like ants. It was astonishing to think that this had been built with little more than bare hands and primitive technology. The general opinion among us men had been that the undertaking was impossible.”

In contrast to Swann’s account, Urquhart also remembered, “Building the bridge was probably the easiest time I experienced on the railway. The work was more about craft and guile than brute strength and physical labour. But it never stopped the guards from making us work at double time or administering beatings for little or no reason whatsoever. On one occasion, I received a severe beating after failing to drill a half-inch hole through a 12-inch-diameter log.”

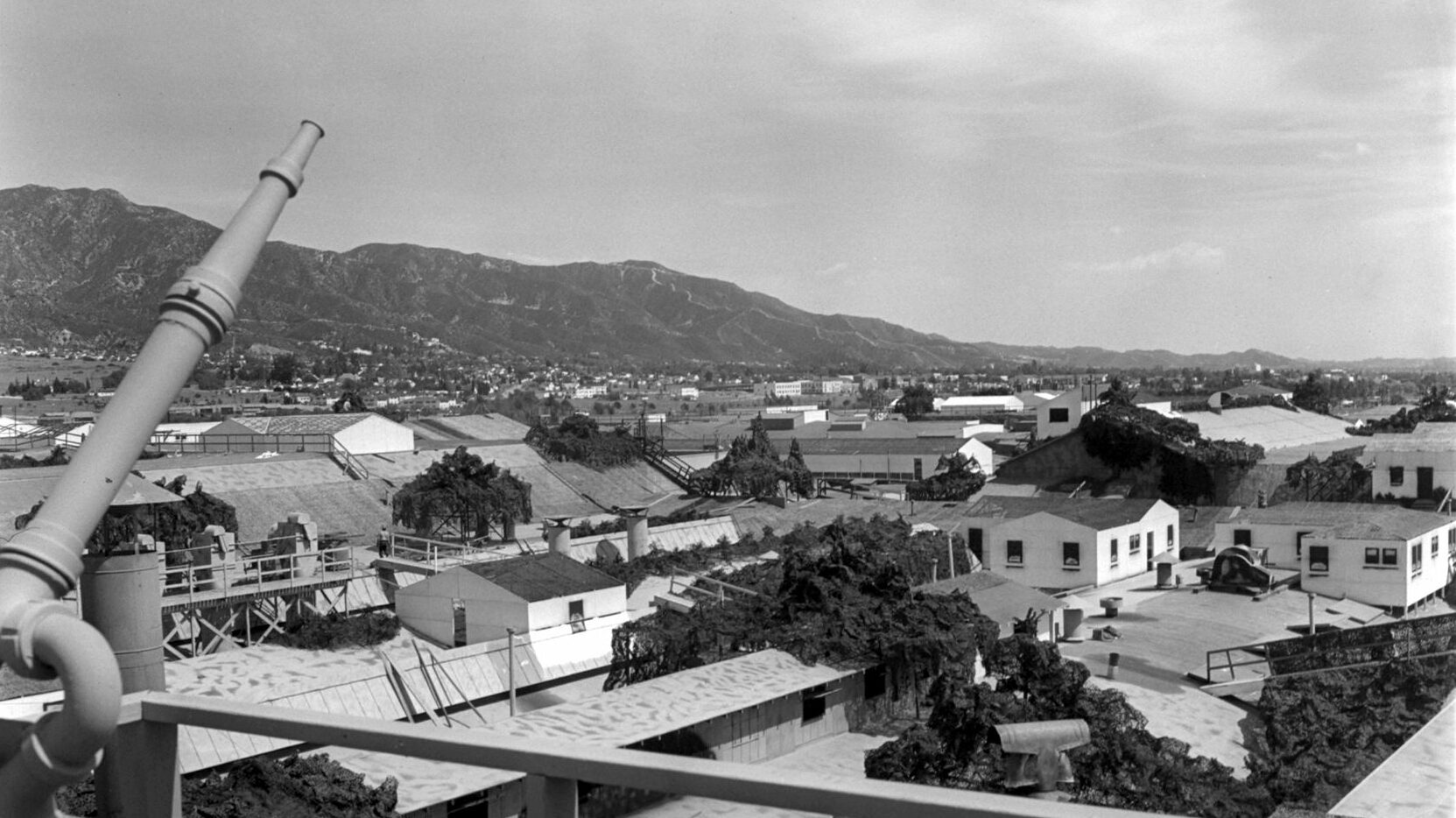

Although the Japanese had attempted to keep the building of the railway a secret, it would not take long for the Allies to discover the construction effort. The sheer importance of the railway, too, was not lost on the British, who mounted a number of air raids in an attempt to disrupt the work of the Japanese.

On February 13, 1945, the RAF conducted a bombing raid on the two Kwai bridges, causing damage to both. However, the Japanese were quick to use forced labor to effect repairs, and by April the wooden bridge was again usable. Another raid took place on April 3, this time by the U.S. Army Air Forces, and further damage was inflicted on the wooden bridge.

Nevertheless, the Japanese were able to get both bridges back in operation by May. On June 24 the RAF was finally able to inflict serious damage to both bridges, putting the railway out of action for the remainder of the war.

Hellfire Pass

Another notorious section of the Burma Railway is Hellfire Pass, located in the Tenasserim Hills. Also known as the Konyu Cutting, it was the deepest and longest cutting of the entire railway and, just as the Bridge on the River Kwai has come to symbolize British suffering, Hellfire Pass is similarly often associated with the Australians’ misery.

The pass itself is some 246 feet long and 82 deep. Much of the work was carried out by hand, with few tools available, making the cutting process particularly difficult. It is said that prisoners would drill a number of holes in the rock, with one man holding a metal drill bit while another hit it on the head with a hammer.

Once this task was complete, the resulting holes were filled with explosives and the rock blasted away. The men would then return to pick up the loose rocks by hand and put them into baskets or sacks, carrying the heavy rubble away in what was tiring and back-breaking work.

Initially, the work on Hellfire Pass was done by some 1,500 British and 2,000 Tamil workers beginning in November 1942. By April the following year, around 400 Australian prisoners from T Battalion of D Force were sent to work on the cutting, and by June a further 600 British and Australian prisoners of H Force were brought up after work had fallen behind schedule. In addition, some 1,000 romusha were also employed in the vicinity.

The Konyu Cutting earned the name “Hellfire Pass” due to the dreadful conditions the prisoners had to endure while working on it. During the infamous period of “Speedo,” the prisoners working on this section of the railway were made to work long hours with little rest or food. Work would carry on late into the evening with oil lamps and bamboo fires lighting the night sky.

To make matters worse, the monsoon rains turned the work camps into little more than swamps full of deep, thick mud, while the steep hill faces became treacherously slippery under foot. Blasting also continued into the night, and the whole scene was a “living hell” to those who experienced it.

One survivor of Hellfire Pass was Alistair Urquhart: “Another squad were tasked with removing the rocks, trees, and debris, another separated the roots to dry them out and later burn them. Meanwhile, on the pickaxe party, some men were going hammer and tong. I said to one chap near me who was slugging his pick as if in a race, ‘Slow down mate, you’ll burn yourself out.’ ‘If we get finished early,’ he said, puffing, ‘maybe we’ll get back to camp early.’ But the soldiers would only find something else for us to do. And then the next day Japanese expectations would be higher.

“Personally, I tried to work as slowly as possible. The others would learn eventually, but I soon discovered ways to conserve energy. If I swung the pick quickly, allowing it to drop alongside an area I had just cleared, the earth came away easier. It also meant that while it looked as if I were swinging the pick like the Emperor’s favourite son, the effort was minimal.

“Nevertheless, under the scorching Thai sun and without a shirt or hat for protection, or shade from the nearby jungle canopy, the work soon became exhausting. Minute after minute, hour after hour, I wondered when the sun would drop and we could go back to camp.”

Besides the punishing working conditions, some 69 men are said to have been mercilessly beaten to death by their sadistic Japanese guards in Hellfire Pass during the 12 weeks it took to complete the work. Many more are known to have died of disease, but it remains uncertain exactly how many prisoners and romusha perished while working on the Konyu Cutting. The site of Hellfire Pass was lost after the war but was found again in 1980, and since 1990 an ANZAC Day ceremony is held there every year.

The “Speedo” Period

Despite the considerable achievements of the Japanese engineers and their reluctant forced laborers, progress on the Burma Railway soon fell behind schedule. In response, the infamous “Speedo” period took place between July and October 1943, during which the conditions of the workers rapidly deteriorated even further.

The Allied prisoners were forced to work around the clock in a desperate attempt to make up time and get the railway back on schedule, with 18-hour shifts becoming common practice. Hardly a day would pass during the Speedo period without the death of a prisoner, with casualty rates climbing sharply. The Japanese guards would be heard aggressively screaming “Speedo! Speedo!” at the prisoners, coercing them to work ever harder and faster.

John Leslie Graham, another British Army POW, recalled the increased brutality of the Speedo period: “All the time that we were working on the track, the Japanese were always shouting ‘speedo.’ We nicknamed one of the guards ‘Speedo.’ They would beat up any prisoner if they thought he wasn’t working hard enough. Another ploy was to make us hold a heavy rock above our head.”

The increased number of deaths saw the need for each of the worker camps to establish a rough cemetery for the burials of those who perished. The Japanese allowed the prisoners to bury their dead, and some even attended their funerals. Bizarrely, although the Japanese behaved indifferently to the suffering of their prisoners during life, they showed them deep respect following their deaths.

Medical care had been limited from the start and became even more so during the Speedo period. The Allied doctors and medics did what they could to relieve the suffering of the sick and injured, coming up with somewhat ingenious methods to help their desperate patients.

Ulcers were a particular problem, often resulting from a small cut on bare feet or legs and becoming infected. Little could be done but to cut away the dead flesh—usually agonizingly scraped away using a teaspoon or similar object—in the hope of preventing the infection from spreading further.

In the worst of cases, amputations without anesthetic would be made using makeshift surgical tools. Nevertheless, the Japanese, demanding better results, forced even the sick to carry on with their work, even though many could hardly walk, let alone perform the back-breaking tasks expected of them.

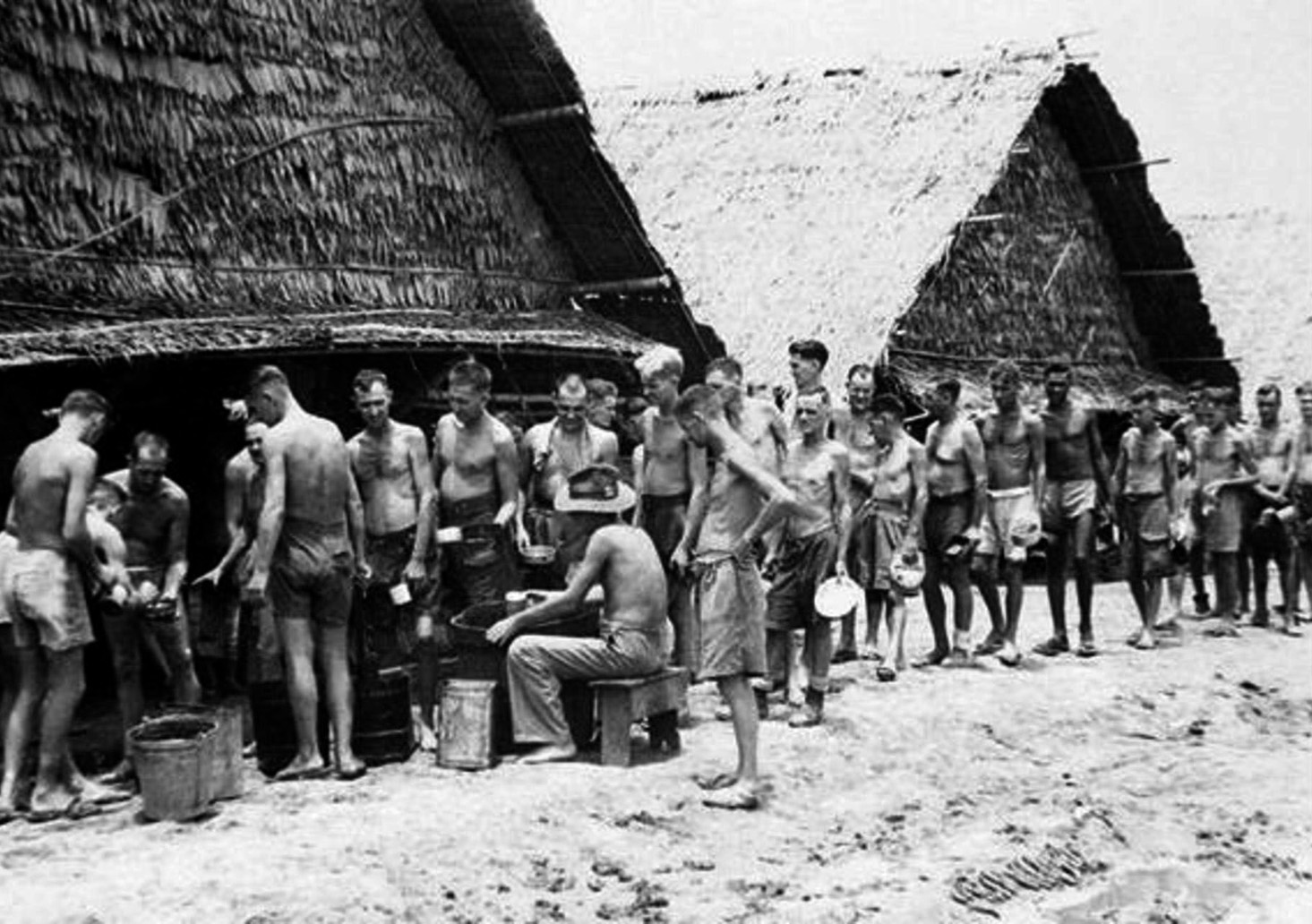

Other diseases among the Allied prisoners also became prevalent, with dysentery and diarrhea accounting for around a third of all deaths. Poor diet also led to conditions such as beriberi and pellagra, caused by the lack of vitamin B1 and niacin, since the Japanese predominately fed the prisoners on rice alone. Mosquitoes carried malaria, which caused around two percent of all deaths, while cholera was also a serious menace, causing around 12 percent of deaths.

One prisoner working on the railway was an Australian doctor named Rowley Richards, who years later recalled how many sick fellow prisoners would often appear to make a recovery only to lose the will to live: “I had always believed that there was a will to live and if that will to live disappeared, well, you died. There’s much more to it than that, I’m sure of that. It’s a bit like bone pointing. You point the bone at yourself, I guess.

“I’ve seen many cases of fellows who have been nigh unto death for maybe a couple of weeks, semiconscious most of the time, being hand fed by their mates, managing to still stay alive. And then when they recover from that and they’re starting to be getting better, or think they’re getting better, they just up and die on you. And I think what happened to them was that they would look around and see fellows dying around them and think, ‘Oh, it’s too hard, no, let me go.’”

As the prisoners increasingly suffered, the Japanese Speedo policy seemed to achieve its goal, since the Burma Railway was ultimately completed ahead of schedule in October 1943. For the Allied prisoners, however, the completion of the project was not the end of their torment. Those who survived until liberation had to endure a further two years in brutal captivity, and many were retained to conduct repairs to the railway as the Allied bombers began to take their toll.

The Workforce: Allied Prisoners of War

Although they formed only a relatively small percentage of the workforce employed constructing the Burma Railway, the Allied prisoners are foremost in the minds of most people when thinking about the forced labor used to build it.

Following the fall of Singapore, the Japanese had taken 127,000 British and British Commonwealth troops prisoner. Another 8,500 were taken prisoner in Java and Sumatra, and to these numbers others can be added, including survivors of Allied ships sunk by the Japanese, aircrew who were shot down and associated ground crews who were left behind when their airfields were overrun, Dutch prisoners seized in Java and Sumatra, and even a number of Americans. In short, the Japanese had access to considerable numbers of men to be used as slave laborers.

Not all these POWs, of course, would ultimately be employed building the railway, although a substantial number of them would be. It is believed that more than 60,000 were involved in some way or other in the construction by the height of activity in mid-1943.

The earliest Allied prisoners to be assigned to the project were about 3,000 Australians who had been captured at Singapore and imprisoned at Changi prison. In May 1942, these men were shipped to Thanbyuzayat in Burma and set to work building the initial infrastructure that would later facilitate the actual work on the railway.

A month later another 3,000 British prisoners were similarly shipped out of captivity at Changi and sent to Ban Pong—the opposite end of the railway from Thanbyuzayat—to perform similar work. Over the coming months, an increasing number of Allied prisoners were transported to Burma to contribute to the work.

The men were forced to work in horrendous conditions, using primitive tools and often resorting to sheer brute force. Embankments were raised, cuttings hacked, and bridges built using materials sourced from local forests.

Although the Japanese fed their workers, the diet of the Allied prisoners was poor, usually consisting of rice and little, if anything, else. The hard physical labor combined with malnutrition soon took its toll on the weakened men, who were particularly susceptible to disease and other dangers of the jungle.

During their time building the railway, they were squeezed into primitive camps that were also not conducive to good health, having basic or no sanitary arrangements and poor to nonexistent medical facilities. Added to this was their brutal mistreatment by the Japanese and their Korean allies, who regularly beat and abused their captives, often in extreme fits of unrestrained violence.

Nevertheless, the prisoners did their best to keep their morale up by employing what forms of entertainment they could when in the camps and not working on the railway. Singing, telling jokes, or even playing music was a common way of relaxing, although they surely never felt truly relaxed during their time in captivity.

E. Samuel, another British prisoner, recalled some of this dubious entertainment: “Entertainment—usually too tired. Permission for concert on half-day rest. Gunner W., an ex-ballet dancer—marvellous morale booster, complete with chorus line dancing, mosquito net tu-tus, and coconut shells. We finished with the National Anthem, all stood to attention, including guards.

“Japs decided they could do as well—we all had to attend—orations, singing—one Korean guard played a mouth organ and finished with ‘a popular English tune,’ the National Anthem.”

Of the more than 60,000 prisoners of war forced to work on the railway, it is believed that around 12,000 died as a result. Many of those who survived would later find themselves in prison camps in Japan, where their treatment was little better, again forced to work in aid of the Japanese war effort. Others were even set to work building other, albeit far less ambitious, railways, such as the Sumatra and Kra Isthmus Railways.

The Workforce: Romusha

Although largely and unfairly forgotten today, the vast majority of workers employed on the construction of the Burma Railway were in fact Southeast Asian civilians, said to have numbered up to 190,000, most originating from British territories overrun by the Japanese.

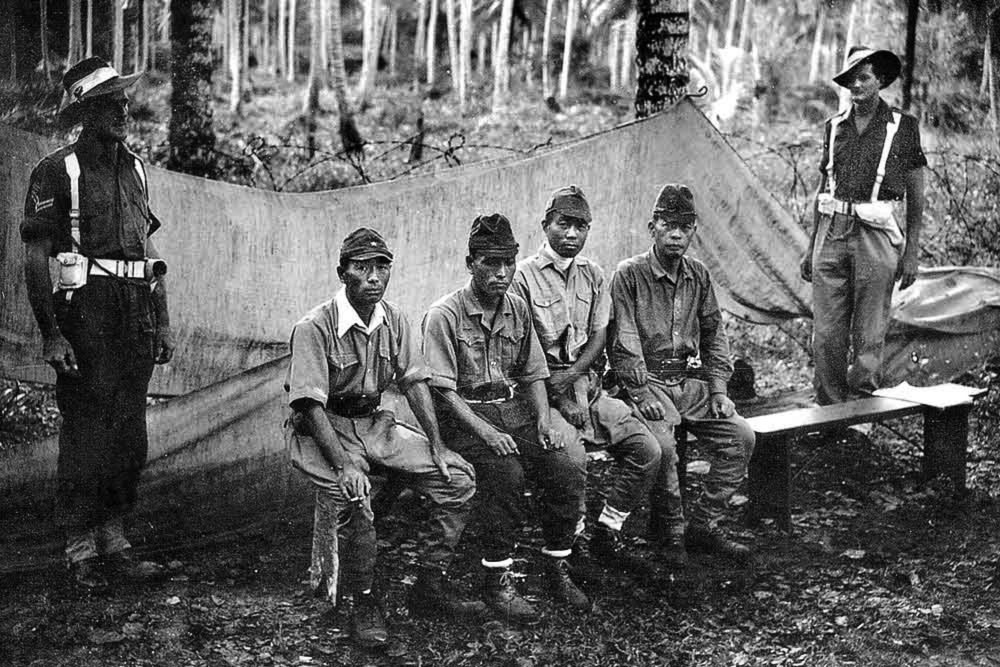

These civilians included Burmese, Chinese, Javanese, Malays, and Thais, among others, who were initially tricked by the Japanese to work on the railway in return for promises of a better life for them and their families. Such promises, of course, were lies and many disappeared as a result. Unable to lure more workers, the Japanese turned to coercive methods, forcing them to undertake their labors.

Romusha is the Japanese word for laborer, and millions of them would be utilized by the Japanese in support of their war effort. Of those who worked on the Burma Railway, it has been estimated that 80,000 to 100,000 perished, figures painstakingly determined from numerous postwar eyewitness statements.

The conditions under which they worked were no better than those suffered by the Allied prisoners, if not actually worse. Although some work has been done by academics on the awful plight of the romusha, very little remains known about their experiences in comparison to the Allied servicemen.

Among some of the most graphic accounts of the Japanese mistreatment of the romusha is that by Robert Hardie, a British doctor who was himself a prisoner of the Japanese: “A lot of Tamil, Chinese, and Malay labourers from Malaya have been brought up forcibly to work on the railway. They were told that they were going to Alor Star in northern Malaya; that conditions would be good—light work, good food and good quarters.

“Once on the train, however, they were kept under guard and brought right up to Siam and marched in droves up to the camps on the river. There must be many thousands of these unfortunates all along the railway course. There is a big camp a few kilometres below here, and another two or three kilometres up.

“We hear of the frightful casualties from cholera and other diseases among these people and of the brutality with which they are treated by the Japanese. People who have been near the camps speak with bated breath of the state of affairs—corpses rotting unburied in the jungle, almost complete lack of sanitation, frightful stench, overcrowding, swarms of flies. There is no medical attention in these camps, and the wretched natives are of course unable to organise any communal sanitation.”

The Workforce: The Japanese and Their Korean Allies

Others who worked on the Burma Railway who are also often overlooked are the Japanese themselves and their Korean allies. Around 12,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army and 800 Koreans were employed on the railway, many of them acting as guards for the Allied prisoners of war or otherwise coercing the romusha.

Others were, of course, military engineers and those with the technical knowledge and expertise to design and build the railway. Some of these men were organized into railway regiments—the 5th and 9th Regiments—that worked directly on the railway. Others of the 2nd Railway Administering Department were tasked with the organization of the prisoner work force, ensuring they did the work and preventing any from escaping.

Conditions for the Japanese, naturally, were somewhat better than those endured by the Allied prisoners and civilian laborers. Food rations were far superior, and medical attention was usually on hand, but they were still exposed to the dangers of working in the jungle and often at risk from disease.

For many, the fact they were assigned to building the railway or guarding the prisoners was felt to be second-class work. Serving on the front lines fighting against the enemy was where the prideful majority wanted to be. Around 1,000 Japanese died working on the Burma Railway, mostly from disease.

There were also a number of inadvertent combat casualties. Housed in huts at the Tamarkan POW camp, the prisoners were caught in air raids against the bridges. The worst took place on November 29, 1944, when an Allied air raid struck the bridge and a nearby antiaircraft battery. Some of the bombs overshot the target and exploded in the camp, killing 19 POWs and wounding 68 others.

Another raid took place of February 5, 1945, in which 15 POWs were wounded; the Japanese then moved the rest of the prisoners to a less vulnerable camp site.

It took eight months for the bridge to be completed, and it remained in operation shuttling troops and supplies back and forth for two years. When completed, the Burma-Thai Railway Line, as it came to be known, stretched 260 miles.

War Crimes

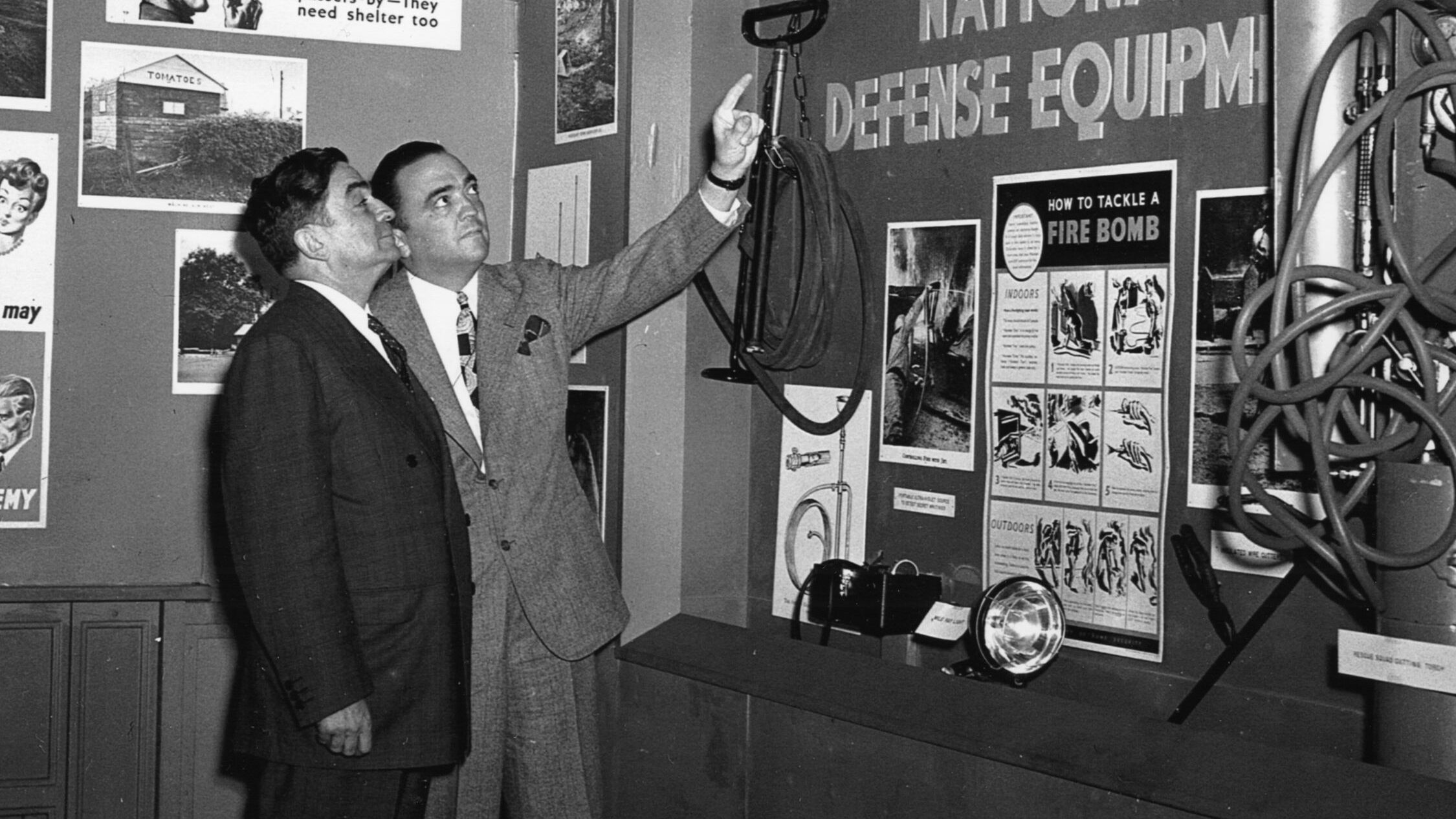

Following the announcement of Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, the Allies rounded up thousands of Japanese soldiers and conducted a number of war crimes trials, including against those who had been responsible for work on the Burma Railway. The collecting of evidence had, in fact, begun long before the cessation of hostilities, and there were many clear cases of murder and brutality against Allied POWs.

These trials, conducted from 1945 to 1951, were categorized into three classes. Class A, which included the charges of conspiracy to wage and start war, were aimed at high-level Japanese politicians and military officers, while Classes B and C were concerned with violations of the laws and customs of war and crimes against humanity. The actual trials were set up and conducted by the various national governments of the Allied nations seeking to bring to justice those who had committed war crimes against their citizens.

Trials of Japanese and Korean personnel who worked on the Burma Railway were carried out in Singapore in 1946 and 1947. Of the 111 convicted, some 32 were given death sentences, while the others received terms of imprisonment or other forms of punishment.

One Japanese NCO who was tried was a sadistic Sergeant Seiichi Okada, who had earned the nickname “Doctor Death.” Okada was a medical orderly stationed successively at Kanu, Hintock, and Kinsayok POW camps in Thailand. He was charged with the inhumane treatment of prisoners, which contributed to a number of deaths and the great physical suffering of others.

Two witnesses, Privates Purdy and Wetherilt, testified against Okada, stating that while they were suffering from dysentery and diarrhea both men were forced to continue their work on the railway despite their acute illnesses. The NCO was found guilty and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Another case was that of Major Totaro Mizutani, who was accused of three separate crimes. First, inhumane treatment of prisoners of war who were working on the Burma Railway, forcing sick prisoners to march more than 200 miles to work while failing to provide adequate food and medical supplies for them. Of roughly 2,000 prisoners in his charge, it was alleged that 570 died. Second, Mizutani was accused of ill treatment of a Burmese civilian who had begged him for food; the Japanese major allegedly burned the victim with a flaming piece of wood. Third, Mizutani was charged with shooting and killing Fusilier L.W. Wanty, a British prisoner, when he was caught wandering outside his sleeping quarters after lights out. Mizutani was sentenced to death by hanging.

It remains unclear exactly how many such trials for war crimes were conducted by the Allies against former Japanese soldiers. However, according to the Singapore War Crimes Trials Web Portal, “Some latest estimates of the number of war crimes trials held by different national authorities in Asia are as follows: China (605 trials), the U.S. (456 trials), the Netherlands (448 trials), Britain (330 trials), Australia (294 trials), the Philippines (72 trials), and France (39 trials).

“In 1956, China prosecuted another four cases involving 1,062 defendants, out of which 45 were sentenced and the rest acquitted. The Allies conducted these trials before military courts pursuant to national laws of the Allied Power concerned.

Altogether 2,244 war crimes prosecutions were conducted in Asia; 5,700 defendants were prosecuted; 984 defendants were executed; 3,419 were sentenced to imprisonment; and 1,018 were acquitted.”

The River Kwai Bridge Today

Today the Bridge on the River Kwai, which still stands largely intact but with some postwar repairs, is a major tourist attraction in Thailand. The track over the bridge has been modified to make a walkway for visitors to cross the bridge on foot, as well as offer viewpoints of the incredible scenery. However, a small train does travel back and forth over the bridge carrying tourists who prefer to experience it via rail. Each year a River Kwai Bridge festival is held to remember the Allied bombing raid of November 28, 1944.

Also of importance to the potential visitor are the three nearby war cemeteries where the bodies of the majority of Allied prisoners of war who perished building the Burma Railway rest. These include the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery near the town of Kanchanaburi itself, which has 6,858 identified casualties. The second is the Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery, containing 3,626 identified remains. Finally, there is the Chungkai War Cemetery, containing a further 1,692 casualties. All three are maintained by Britain’s Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

After film director David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai came out in 1958, many of the actual survivors were less than pleased to see that some of the British troops who worked on the bridge were portrayed as collaborating with the enemy to finish the structure on time.

One man, Ernest Gordon, said, “In justice to these men—living and dead—who worked on that bridge, I must make it clear that we never did so willingly. We worked at bayonet point and under bamboo lash, taking any risk to sabotage the operation whenever the opportunity arose.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments