By David Alan Johnson

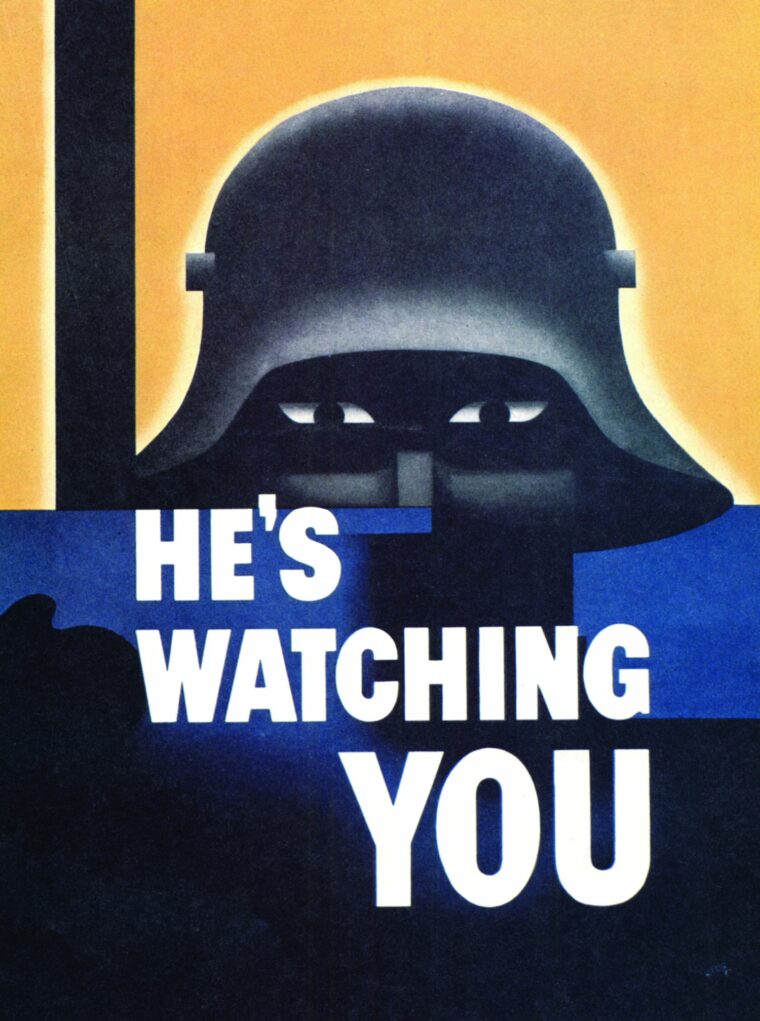

Throughout his lifetime, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover always boasted that no enemy agent, either spy or saboteur, ever operated at large in the United States during World War II. The FBI’s record against spies and saboteurs was perfect, Hoover insisted. Clandestine enemy activity had been “kept under control” throughout the war, and no “military secrets” had been smuggled out of the country by either German or Japanese agents. Any and all spies who entered the United States had been captured and rendered harmless.

Hoover never found out how wrong he was. For nearly two years, a German agent had sent hundreds of reports from a secret radio transmitter in New York to contacts in Germany. And nobody in the FBI, including Hoover, ever found out.

A Sleeper Agent in the City That Never Sleeps

The agent who managed to send all that information, right under the FBI’s nose, was anything but a super spy. He was a 51-year-old Dutch national named Walter Koehler, a fat, bald, near-sighted little man with horn-rimmed glasses and bad teeth. Although he had been trained in espionage, Koehler owed at least part of his success to good luck and the complacency of J. Edgar Hoover.

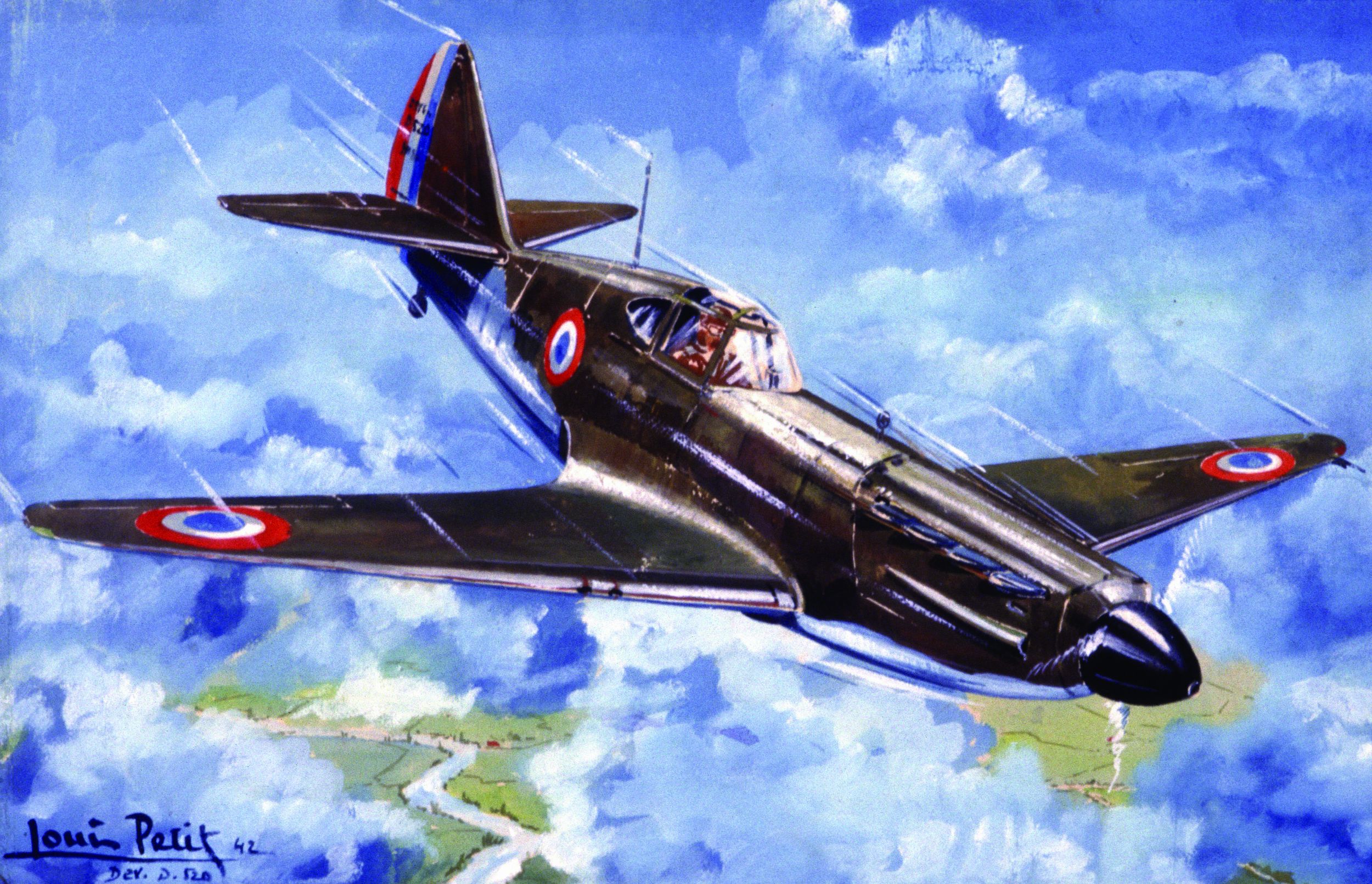

Koehler had been chosen to go to the United States on an espionage assignment mainly because of his technical and engineering background. German intelligence knew that American scientists had been experimenting with nuclear fission for some time. Articles in U.S. scientific journals, along with stories in the New York Times and other newspapers, described atomic energy in general terms and also discussed the power of an atomic bomb as a weapon. A German spy named Alfred Hohlhaus had also sent a number of reports on American nuclear research, along with as much information as he could get regarding the U.S. atomic program. Hohlhaus, incidentally, also operated without the knowledge of J. Edgar Hoover or the FBI. The Luftwaffe was especially interested in knowing if the United States was close to making a bomb.

To find out, German intelligence decided to send Walter Koehler to the United States. Koehler had studied engineering and is usually described as being technically minded. He had also worked for German intelligence during World War I, which gave him several years of practical experience in espionage in addition to training and instruction in “spy school.” Just as important as his technical background and his experience, Koehler had also spent several years in the United States. He was a sleeper agent in New York from the late 1930s until 1941.

Koehler was recalled to Germany in 1941 because of some irregularities in his bookkeeping. His superiors wanted to know why he was not able to account for some of the funds that he had been issued for operating expenses. The explanation Koehler gave must have been quite a good one; whatever it was, it kept him out of prison. Or maybe German intelligence needed someone with a devious nature and decided to put it to work for them instead of against them.

After being chosen for his new assignment, Koehler was given a sort of cram course in nuclear physics, a class in the basics of atomic energy and technical terms related to it. In the summer of 1942, he was sent on his way to New York via Madrid. It was decided that his wife would go with him. Mrs. Koehler’s presence was part of Koehler’s disguise. No one would ever think that a fat, middle-aged man and his plump wife might actually be German spies.

Turning Himself In

Mr. and Mrs. Koehler would need visas before they could to enter the United States. These could be applied for in Madrid, before the Koehlers left for New York. They took a train to Madrid, where Koehler presented himself at the U.S. consulate to apply for permission to enter the country. The entire procedure was normal and routine at first; no one questioned the false identification documents that had been provided by German intelligence. When Koehler sat down to be interviewed by a member of the consulate’s staff, however, Koehler shattered the routine and left the young official speechless with astonishment.

Koehler told his interviewer that he was a German espionage agent and that he wanted to turn himself over to the American authorities. This threw the entire process into a cocked hat; it was no longer just an ordinary matter for some junior official, but a request for political asylum. The vice counsel was summoned to hear what else Koehler had to say and was as amazed as his predecessor had been. Koehler’s story sounded like something out of a Hollywood film.

He was being sent to the United States to set up a secret radio station, Koehler explained, and he went on to say that his job would be to send reports on U.S. troop departures for overseas. But, he went on, he did not want to work for the Nazis. The only reason that he accepted the assignment was to escape. He was Roman Catholic and anti-Nazi in German-occupied Holland, which did not offer a very promising future. He wanted to get away before he said or did something that landed him in a concentration camp. Instead, he wanted to work against the Nazis as a double agent, sending authentic-sounding information to Germany that was actually false.

To prove that he really was a bona fide German agent, Koehler showed the consulate staff the paraphernalia that he had been issued by German intelligence—his code book, the operating manual for his radio, his schedule for transmitting reports to his contact in Germany, and $6,230 for operating expenses.

The consulate staff believed Koehler but did not know what do with him or his wife. Finally, after talking it over for some time, they decided that the best thing would be to contact the U.S. State Department in Washington. As soon as the staff at the State Department heard the phrase “German spies,” they immediately telephoned the FBI.

A Rough Journey to America

When J. Edgar Hoover heard the story, he recommended that the Koehlers be granted their visas. Hoover did not really care if Walter Koehler was a spy or a refugee. As far as he was concerned, Koehler was an opportunity for publicity, and he would take full credit for any harm Koehler did to the German intelligence network.

With Hoover’s full knowledge and blessing, the Koehlers boarded a neutral Portuguese ship in August 1942 and began their trip to New York. But midway across the Atlantic, Koehler developed a severe case of pneumonia, so severe that the captain decided to send for help. The ship did not have the medical staff to treat anyone in Koehler’s condition, so the captain hoisted the international distress signal, hoping that a passing ship would see it and come to assist.

Fortunately for Walter Koehler, a U.S. Coast Guard vessel happened to be close by and went to investigate. The Coast Guard removed Koehler from the Portuguese ship and rushed him to a hospital in Florida. No one notified the FBI, however. When the Portuguese ship docked in New York, federal agents were highly annoyed, to put it mildly, when they discovered that Walter Koehler was not on board. It took some frantic searching and a few threatening telephone calls from J. Edgar Hoover before Koehler was located.

The FBI’s German Agent

As soon as Koehler recovered from his pneumonia, the FBI set him up as their very own German agent. The Bureau gave Koehler his own radio station on Long Island, installed in a large secluded house, and surrounded it with a solid wall of security. No one was allowed anywhere near the station except a handful of carefully screened FBI agents. Guard dogs patrolled the grounds. Three agents ate, slept, and lived in the house; one man was always on duty to keep watch.

Koehler was not allowed to send his own messages to Germany. Hoover did not trust him. An FBI agent who had learned to copy Koehler’s “fist,” his own unique way of pounding out dots and dashes on the telegraph key, sent the reports and signed Koehler’s name. When the first message was sent, on February 7, 1943, Koehler was not even present. Five days later, Koehler’s contact in Hamburg sent a reply, conveying his “thoughts and good wishes” and admonishing Koehler to use “caution and discretion” when sending future signals. Koehler never saw it.

A steady stream of reports was sent to Germany by federal agents. A schedule had been arranged. Signals would be sent by the FBI every Saturday or Sunday at 8 am to Koehler’s contact in Hamburg. Replies would then be radioed by Hamburg on the following Friday or Saturday at 7 pm. Among the items sent to Hamburg on a regular basis were weather reports, data on ships under construction and undergoing repairs, and troop departures for the British Isles, along with unit identification and insignia. Most of this would either become common knowledge—U.S. Army insignia would not remain secret very long after American troops came ashore on D-Day—or had been doctored to alter the facts. All information that was sent had been cleared by the armed forces and classified as harmless.

No news on the U.S. atomic bomb project, not even misleading reports, was ever sent. Although Soviet spies and Americans sympathetic to Soviet communism managed to smuggle atomic secrets to Russia, there is no record of any U.S. nuclear technology ever reaching Germany. But German intelligence did not care. They were more than happy with the information they were receiving.

The FBI was also more than pleased with what was taking place on Long Island. The Germans seemed to be swallowing everything whole; the ruse was working perfectly. Hamburg sent Koehler congratulations for a job well done on several occasions, along with birthday best wishes, and Christmas and New Year’s greetings (in both 1944 and 1945). Federal agents responded by sending their own best wishes and fond regards. They could afford to be agreeable. They were doing an incredible job of misleading and generally making total fools of their counterparts in Germany.

The ruse continued throughout the rest of the war. In the spring of 1944, Koehler informed Hamburg that “a number of armored and infantry divisions” that had originally been scheduled to be sent to Britain, for the D-Day build-up, were being diverted to the Mediterranean for a “special operation.” There was no such operation. It was another bit of misinformation carefully cooked up to fool the Germans.

During all this time, Walter Koehler seemed perfectly content to sit back and let the FBI send false information in his name. He and his wife lived comfortably in a New York hotel, subsisting on an allowance that was doled out from the operating funds the American authorities had confiscated from them.

“The Spy Who Double-Crossed Hitler”

Some of the federal agents assigned to keep an eye on Mr. and Mrs. Koehler did not completely trust their charges. The two always seemed to have more money than they were being allotted, although nobody could figure out where they got it. Also, they seemed to be a little shadowy and mysterious for a pair of simple Dutch political refugees. But no one had any proof of anything; there were nothing but vague suspicions.

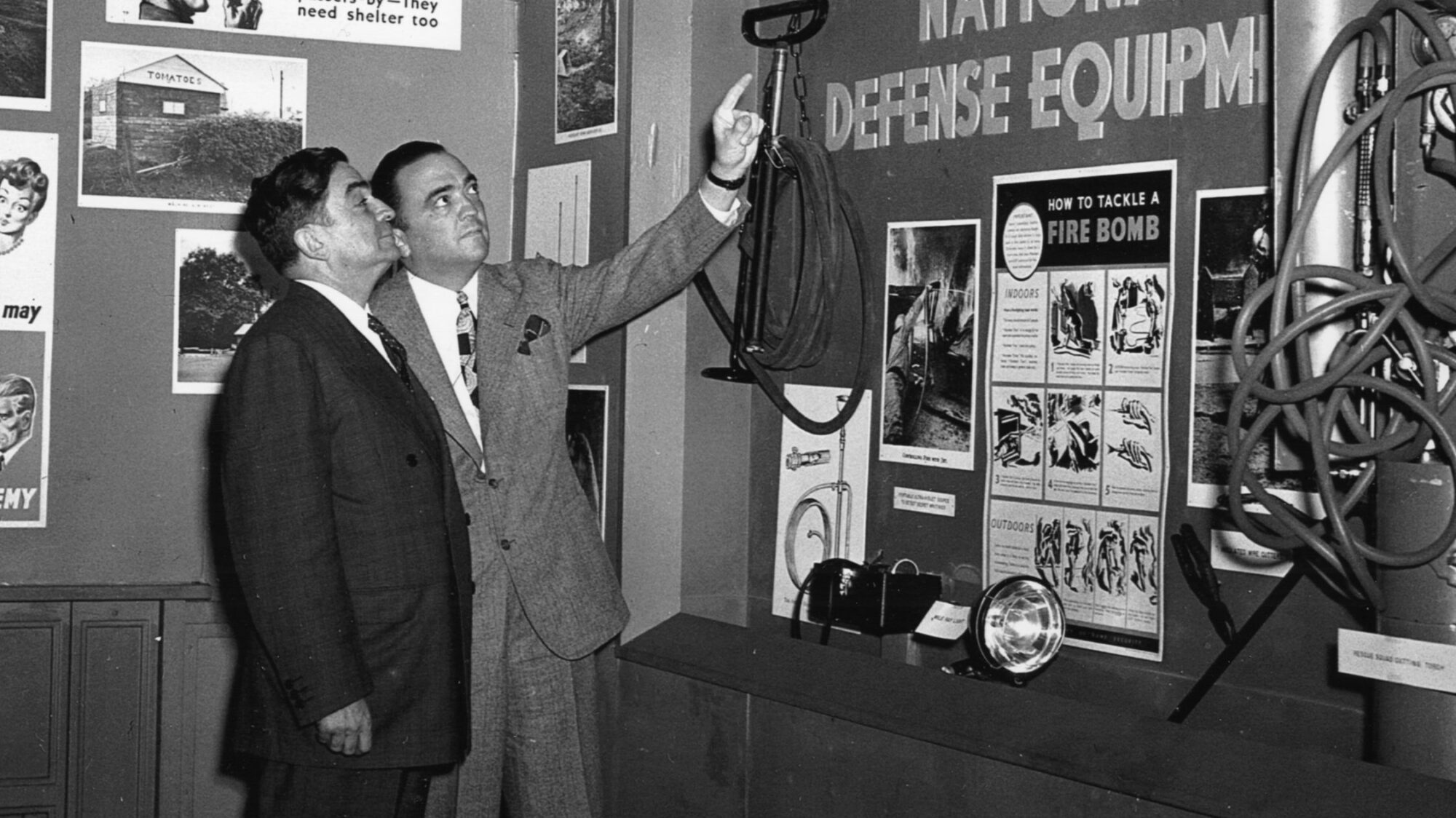

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover entertained no such suspicions. He was more than pleased with himself for having used the German spy to suit his own purposes. Hoover was so proud of his work in the Koehler affair that he wrote his own version of it in a magazine article. “The Spy Who Double-Crossed Hitler” appeared in an American magazine in May 1946. In the article, Hoover called Walter Koehler “Albert van Loop” and described how he and his bureau completely tricked and misled German intelligence by sending all manner of falsified information.

According to Hoover, he “succeeded on all scores” with the Koehler hoax. Among other accomplishments, he claimed to have deceived the German High Command regarding the time and place of the D-Day landings. Koehler/van Loop had done exactly what Hoover wanted him to do, although he cooperated “with a pistol at his back.”

A Triple Cross

Hoover’s account was the only known version of Walter Koehler’s story for over 25 years. In the 1970s, after Hoover’s death in 1972, the Hungarian-born American writer Ladislas Farago came across Walter Koehler’s dossier in Germany. Farago was researching a book about German intelligence during World War II and discovered Koehler’s file in the German war archives. He recognized some of Koehler’s signals from quotes in Hoover’s magazine article, but he also noticed that there were a lot more messages than the 115 signals sent by FBI agents in Koehler’s name. Something was not right.

The German files listed more than twice as many messages received by Hamburg than the FBI claimed to have sent. On March 4, 1944, the FBI noted that signals number 63, 64, and 65 had been transmitted. But the German file detailed that Koehler had sent 137 messages by that time. Some of them had been sent in a code that was completely different from the Long Island station’s cypher. It became clear that Walter Koehler had been working independently from the FBI. Federal agents had been sending their signals to Hamburg, while Koehler had been sending his own.

Walter Koehler had not been double-crossing Hitler. He had been triple-crossing J. Edgar Hoover and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. While federal agents were busy sending falsified information to Germany in Koehler’s name, Koehler had been sending authentic reports to his contact in Paris. Hamburg knew all along that the messages it had been receiving were phoney.

Farago also interviewed three former members of the German secret intelligence service. All three remembered Walter Koehler, including his eyeglasses and bad teeth, and gave Farago another surprise. Koehler’s double agent ploy, as well as his request for political asylum, had been prearranged by his superiors in German intelligence. The story handed to the vice consul’s staff in Madrid had been worked out well in advance. Koehler’s willingness to work for the FBI had also been rehearsed; the story gave him the perfect cover for his real assignment and also guaranteed his entry into the United States.

Transmitting Messages Back to Germany

Most of Koehler’s reports were smuggled out of the country via courier, crossing the Atlantic aboard ships flying a neutral flag. They would arrive at a port in Spain or Portugal and would have Koehler’s secret information in German-occupied Paris within a few days.

If some piece of information was too important to be sent via steamer, Koehler had access to a secret radio transmitter in Rochester, New York, which was operated by another of Koehler’s contacts. The man from Rochester would come to Manhattan to pick up Koehler’s data and would send it off to Paris as soon as he returned to Rochester. To avoid being detected, the Rochester station was used only when speed was of the essence and the information was too vital to be sent by the usual method. When the Germans were driven out of Paris in August 1944, Koehler’s messages went to a radio station in Sigmaringen, in southwest Germany.

One of the radio messages concerned the Allied landings in France on D-Day. “According to rumours circulating here, the invasion appears to be a success,” Koehler said. “I am convinced that this is a gross exaggeration and that all will end well … Barometer reading at 9 o’clock this morning 30 point 20. Greetings, Koe.”

Federal agents observing the Koehlers were right when they thought they had more money than their allotment. They had turned $6,000 over to the U.S. authorities but had been given $16,000 for expenses. Koehler’s corpulent wife had smuggled the additional $10,000 into the country in her girdle, right past federal agents and everybody else. It supplemented the FBI’s allowance very nicely and allowed Mr. and Mrs. Koehler to live beyond their means. In 1943, $10,000 was a great deal of money, more than most people earned in several years.

The Best German Spy of the War

Although Koehler never had access to any atomic secrets, his superiors in Germany considered him the best spy they had during the war. When the secret intelligence service was revamped in 1944, a good many active agents were found to be deficient and dismissed. But Koehler remained throughout the war. His last message was sent on April 26, 1945. Hitler killed himself four days later, and Germany surrendered less than two weeks after that. If the war had continued, Koehler would have gone on sending his signals indefinitely.

“The Spy Who Double-Crossed Hitler” had put one over on the FBI, thoroughly and completely. Much of this was carried out during a critical period, when the German High Command was in desperate need of data concerning U.S. troop movements during the build-up for D-Day. And J. Edgar Hoover never had the slightest suspicion.

David Alan Johnson has written extensively on World War II for more than 20 years. His book The Battle of Britain: The American Factor was well received in both the United Kingdom and the United States. He is currently working on a book about Anglo-American relations since colonial times.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments