By Sam McGowan

In 1942, many Americans considered anyone of Japanese ancestry to be an enemy, regardless of where they had been born or how long their families had lived in the United States. No one took time to consider their loyalties—they just assumed that anyone of Japanese ancestry was rooting for Japan.

Never mind that far more Americans were of German or Italian ancestry than those whose roots were in Japan. They were of European stock and assimilated into American society, while Japanese Americans had distinctive features denoting their Asian ancestry and setting them apart. Rumors spread that Americans of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast were acting as spies for Japan, and in February 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt succumbed to political pressure and signed an executive order authorizing the forced removal of all Japanese from the West Coast for relocation to internment camps.

The controversial decision represents a dark time in the American experience, as many young Americans felt that their constitutional rights were being violated. Yet, in spite of hostility and outright hatred, many young Japanese Americans entered the armed forces and fought heroically, particularly in the European Theater. One young soldier fought in four theaters and was the only American of Japanese ancestry to fly bombing missions against Japan. His name is Ben Kuroki.

Recruited to the Army Air Corps

Although his parents had been born in Japan and immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s, Ben was fortunate to have been raised in the Midwest, where racial intolerance and prejudice were mild, if not downright nonexistent, in comparison with other areas. The lack of prejudice is reflected in Ben’s election as vice president of his senior class at his high school in Hershey, Nebraska, and his positions on the varsity basketball and baseball teams.

The fact that he was living in the Midwest probably had a lot to do with Ben’s enlistment in the U.S. Army Air Corps. As soon as the family got word of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Ben’s father—who had adopted the English name Sam—encouraged Ben and his brother Fred to enlist in the military and fight against Japan. The two young brothers immediately went to the Army recruiting station in nearby North Platte, where they underwent enlistment physicals. After they were found to be qualified for military service, they were told to go back home and wait for notification to report for induction. It appeared that the War Department had yet to decide how to handle Japanese American men of military age who wanted to enlist.

The two brothers waited about two weeks, until they heard an announcement on the radio that the Air Corps was taking recruits at Grand Island. Ben telephoned the recruiting sergeant, told the man he and his brother were Japanese Americans, and asked if that would be a problem. The recruiter said it was not a problem, that he got two dollars for everyone he signed up, and for them to come on over and he would swear them in. They drove 150 miles to the recruiting station and soon were Army Air Corps recruits.

Preparing For War, Fighting Prejudice

Once they were in uniform, they encountered the prejudice that they had been spared growing up. They were now part of a military that bristled over the recent attack on Pearl Harbor and were greeted with outright hatred by many of their fellow recruits, including some NCOs and officers who were responsible for turning young men into soldiers. Ben found himself on KP constantly. Fred fared even worse. He was kicked out of the Air Corps and transferred to the engineers to do ditch digging and other common labor.

Ben was more fortunate than his brother. Upon completion of basic training he was sent to Fort Logan, Colorado, for clerical training, which would keep him inside doing paperwork instead of out in the hot sun doing manual labor. Upon completion of the administrative course, he was sent to Barksdale Field at Shreveport, Louisiana, where he was assigned to the 93rd Bombardment Group, which was training for combat with the Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bomber. The 93rd was the second Army Air Corps unit to equip with the new B-24.

Ben was assigned to the 409th Bombardment Squadron as a clerk-typist in the orderly room, where he typed orders and filed paperwork. His ancestry caused considerable problems; some senior NCOs decided they did not want any Japanese in the squadron and were determined to get rid of him.

When the group got orders to transfer to Fort Myers, Florida, to prepare for overseas duty, a senior NCO redlined Ben’s name on the movement order, which meant he would be left behind. Fearful that he would spend the rest of the war on KP, Ben decided to fight back. He appealed to the squadron adjutant, Lieutenant Charles Brannon, requesting that he be allowed to remain with the squadron. Seeing the tears in the young man’s eyes, Brannon reinstated him on the order.

After training at Fort Myers, the 93rd was ordered to Grenier Army Airfield, New Hampshire, to prepare for the move to England, where the group would be the first B-24 unit assigned to the fledgling Eighth Air Force. Once again, Ben’s name was scratched from the movement order. This time it was the chaplain, Lieutenant James A. Burris, who interceded on his behalf.

Chaplain Burris went to Lieutenant Brannan and pointed out that there was no military policy that prevented a Japanese American from going overseas. Brennan called Colonel Edward J. “Ted” Timberlake, the group commander who was already in New Hampshire, for guidance. Timberlake ordered that Kuroki remain in the squadron.

Ben Kuroki Becomes a Gunner

By October all of the airplanes, aircrews, and ground personnel had arrived in England. On October 9, the group flew its first mission, a cross-Channel operation against Lille, as the first B-24 group in the Eighth Air Force. As a clerk, Ben was not part of the operations. He spent his time in the 409th orderly room typing flight orders and keeping track of squadron records. It really was not the kind of military life he had in mind when he joined the Air Corps.

After the squadron arrived in England, Ben began spending a lot of time out on the flight line, usually helping the armament specialists who were responsible for the .50-caliber machine guns on the four-engine bombers. As a farm kid from Nebraska, Kuroki was no stranger to firearms. He owned a shotgun and hunted ducks and geese along the river by the family’s farm. He soon knew the .50-caliber machine guns so well that he could strip them down and reassemble them while blindfolded. He was also able to get in some target practice.

In 1942, the Army Air Forces were in their infancy, and no training program had been developed for aerial gunners. Pilots had the option of picking their own enlisted crew members from among squadron ground personnel, and Ben was constantly pressing for aircrew duty. Most enlisted aircrew members had been trained in skills directly related to aircraft and systems maintenance or were trained as radio operators, but the need for aerial gunners allowed pilots to choose whomever they wanted as a replacement when there was a vacancy on their crew.

Ben’s chance finally came when Lieutenant Jake Epting suddenly had a vacancy on his crew when his tail turret gunner was medically grounded. Epting told Kuroki he was his new gunner. The assignment meant flying status and silver wings along with a promotion to NCO rank. Coincidentally, the promotion was effective December 7, 1942.

A day or so later, the 409th joined two other squadrons of the 93rd on a temporary deployment to North Africa. Crew members flew their first combat mission with Ben along on December 13, a raid on the docks and supply depot at Bizerte, Tunisia. Their airplane was struck by flak, and a piece of shrapnel struck Sergeant Elmer Dawley in the head. When a crew member started to administer morphine to the injured airman, Ben quickly intervened, pointing out that the drug should not be administered for a head injury. His quick action probably saved Dawley’s life.

“The Most Honorable Son”

Kuroki later reported that the first year of the war had been the most difficult of his entire life. As a Japanese American surrounded by young men who hated “Japs” in a country where wartime propaganda instilled such ideas, he was often lonely and constantly worried that he would do something that would cause him to be kicked out of the squadron.

Once he became part of a combat crew, however, he felt that he belonged. No one questioned him about his nationality anymore, and the rapport among the crew was something he had not experienced before in his year in uniform. The 93rd remained in North Africa for several weeks and did not return to England until February 1943. By that time Ben Kuroki had become an accepted member of the squadron by the combat crews, and his fellow crew members had started calling him “the Most Honorable Son.”

Captured in Spanish Morocco

The 93rd’s B-24s began departing their North African base at midnight on February 23 for the first leg of their flight back to England. Planning for the return called for a fuel stop in Algiers. Daybreak found all of northwest Africa socked in with heavy fog. Each crew was flying on its own, and no attempt was made to maintain any kind of formation.

The bad weather presented two options—pull back power on the engines and head for Gibraltar while keeping their fingers crossed that the weather would be OK when they got there, or enter a holding pattern until the fog lifted at Tafaraoui airfield near Algiers. Epting’s crew did not make it back to England with the rest of the squadron.

The radio range station at Tafaraoui had not been operating when they flew over it, and the navigator lost his bearings. Their airplane ran out of fuel over Spanish Morocco, and Epting was forced to put the bomber, a B-24D named Red Ass, down in a forced landing, a dangerous enough action that was made more so at night. Epting managed to make out some fairly level ground in the darkness and landed the bomber with no damage and no injuries to the crew.

As soon as the crew members emerged from their airplane, they found themselves surrounded by Moroccan militiaman. Curious natives were soon crawling all over and through the airplane looking for loot. A Spanish officer rode up on horseback and ordered that theAmerican men be moved to a nearby town, where they were thrown in the local jail. There were 15 men in all. In addition to the 10-man crew, five ground crew had been on the airplane as passengers.

There was a British consul in the town, and the men were given civilian clothes. The consul notified the U.S. State Department that the men were safe but were to be interned by the Spanish government since they had landed in neutral territory. The jailers were kind to the men, providing decent food, toothbrushes, clean beds, and blankets.

In spite of the decent treatment given the rest of the crew, Ben Kuroki was worried. Being of Asian ancestry, he feared that he would somehow come into contact with Germans, who might realize he was Japanese American and take some kind of action against him even though the Moroccans thought he was Chinese. He decided to head out for the French Moroccan border, which the crew reckoned was about 20 miles away.

Disguising himself as an Arab by turning his raincoat inside out and splattering it with mud and fashioning a turban out of underwear, Kuroki set out to make his way to French territory. But the rugged terrain along the border proved difficult and after two days wandering in the hills Ben was picked up by local authorities.

After spending several days in a cell with some “naughty” Arabs, he was put aboard a Spanish Air Force Junkers Ju-52 transport and flown to Spain. There he was interned along with more than 20 other Allied soldiers of mixed nationality. He was eventually reunited with his crew, but they remained in captivity, although as internees in a neutral country rather than as prisoners of war. While they waited, U.S. and British agents were making arrangements for them to return to Allied control.

The internees ended up in Alhama de Aragon, a Spanish mountain town northeast of Madrid, where they were put up in a hotel that had been arranged for by the U.S. embassy. Several other Allied flyers were in the hotel, along with a couple of Frenchmen. The men were free to wander around the town, where they attracted the attention of the female population, but were advised to be cautious because of Nazi Germany’s previous support of the Franco government.

About a month after they left North Africa, part of the crew was repatriated. Ben and three other members, two gunners and a ground crewman, remained for another month, and some members of the group would not be released until June. Their B-24, undamaged in the emergency landing, was claimed by the Spanish Air Force. A Spanish crew flew the airplane out of Morocco, and it was repainted in Spanish colors.

Ted’s Traveling Circus

When the crew returned to England, they discovered that the 93rd had become famous. Thanks to several dispatches in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, the group was now known as Ted’s Traveling Circus in recognition of their time in Africa. The group’s three squadrons had moved from Northwest Africa, where they were originally assigned to General Jimmy Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force, to Libya where they operated with other Liberators assigned to General Lewis Brereton’s Ninth. A fourth squadron had remained in England for experiments in night intruder missions into Germany, but the project was abandoned and the group was back to four squadrons, the 328th, 329th, 330th, and 409th.

As the only Nisei, or second-generation Japanese American born in the United States, flying combat in England, Kuroki was interviewed by Hollywood personality Ben Lyon, who was serving in the U.S. Army, for a broadcast on NBC in the United States and the BBC in Europe. Lyon was a well-known actor who had starred in Howard Hughes’s Hells Angels in 1930. Lyon and his wife, actress Bebe Daniels, put the young airman at ease with small talk about Hollywood, and he came across in the interview that was heard around the world as a modest man with strong determination. It was the first of many such interviews and public appearances Kuroki would make. He had become the first Japanese American hero of World War II.

Having lost their original airplane in the emergency landing in Spanish Morocco, Epting and his crew were given a new one when they got back. Censorship had taken hold in the Eighth Air Force, and Epting was not allowed to name the new B-24 Red Ass II, so he instead relied on his home town of Tupelo, Mississippi, and gave the airplane the name Tupelo Lass. The crew’s first mission after they were all reunited in England was against German submarine pens and shipping facilities at Bordeaux, France, on the Bay of Biscay.

Epting’s crew was not aboard Tupelo Lass that day, but flew in another airplane named Sex Appeal. The airplane lost power and stalled at 21,000 feet, and in the fall to 2,000 feet gasoline from the engines came into the tail turret where Ben was manning his guns and soaked his flying clothes.

Operation Tidal Wave: Bombing Ploesti

The men of the 93rd were not long in England. Allied war planners had authorized an ambitious mission against the oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania, originally code-named Operation Soapsuds. At Ploesti, facilities produced most of the gasoline, diesel fuel, and other oil products used by Axis forces in the Mediterranean.

The 93rd and its sister group, the 44th Bombardment Group, were taken off combat operations and began training for the mission, which was to be flown at treetop height in order to increase bombing accuracy and achieve a level of surprise. Due to the distance to the target from the nearest possible launch points around Benghazi, Libya, the B-24 was the only bomber in the Allied inventory capable of such a mission. The two Eighth Air Force groups would go to North Africa to join the 98th and 376th Bombardment Groups of IX Bomber Command. A fifth group, the 389th, was still en route to England from the United States and would hook up with them in Africa.

After training at low level for several weeks in England, the 44th and 93rd flew south to Libya. Once again Ben and his crew and squadron mates found themselves on African soil flying missions against German and Italian targets. Although they were there for the Ploesti mission, they were put to work on missions with the Ninth Air Force B-24s against targets around the Mediterranean, including the first mission against Rome.

Allied troops were preparing to land on Sicily and the Eighth Air Force Liberators were used to swell the formations put up by IX and XII Bomber Commands on missions in support of the invasion. Then, on August 1, 1943, the five B-24 groups set out for Ploesti.

Epting’s crew was joined by the 409th squadron commander, Major Kenneth “K.O.” Dessert, who occupied the left seat while Epting flew as copilot in his own airplane. Kuroki, who now had a reputation as one of the best gunners in the group, flew in the top turret. It was a mission Kuroki and other survivors would never forget.

Although the 93rd bombed the target, it was not without heavy loss. The German forces had picked up the assembling B-24s while they were still over the Libyan desert and had tracked them across the Mediterranean, deducing that they were headed for Ploesti. An unfortunate navigational error caused the lead group, the 376th, to turn early and miss the target, an error that the new 93rd group commander, Lt. Col. Addision Baker, recognized. Ted Timberlake had been promoted to brigadier general and moved up to command all B-24s in England.

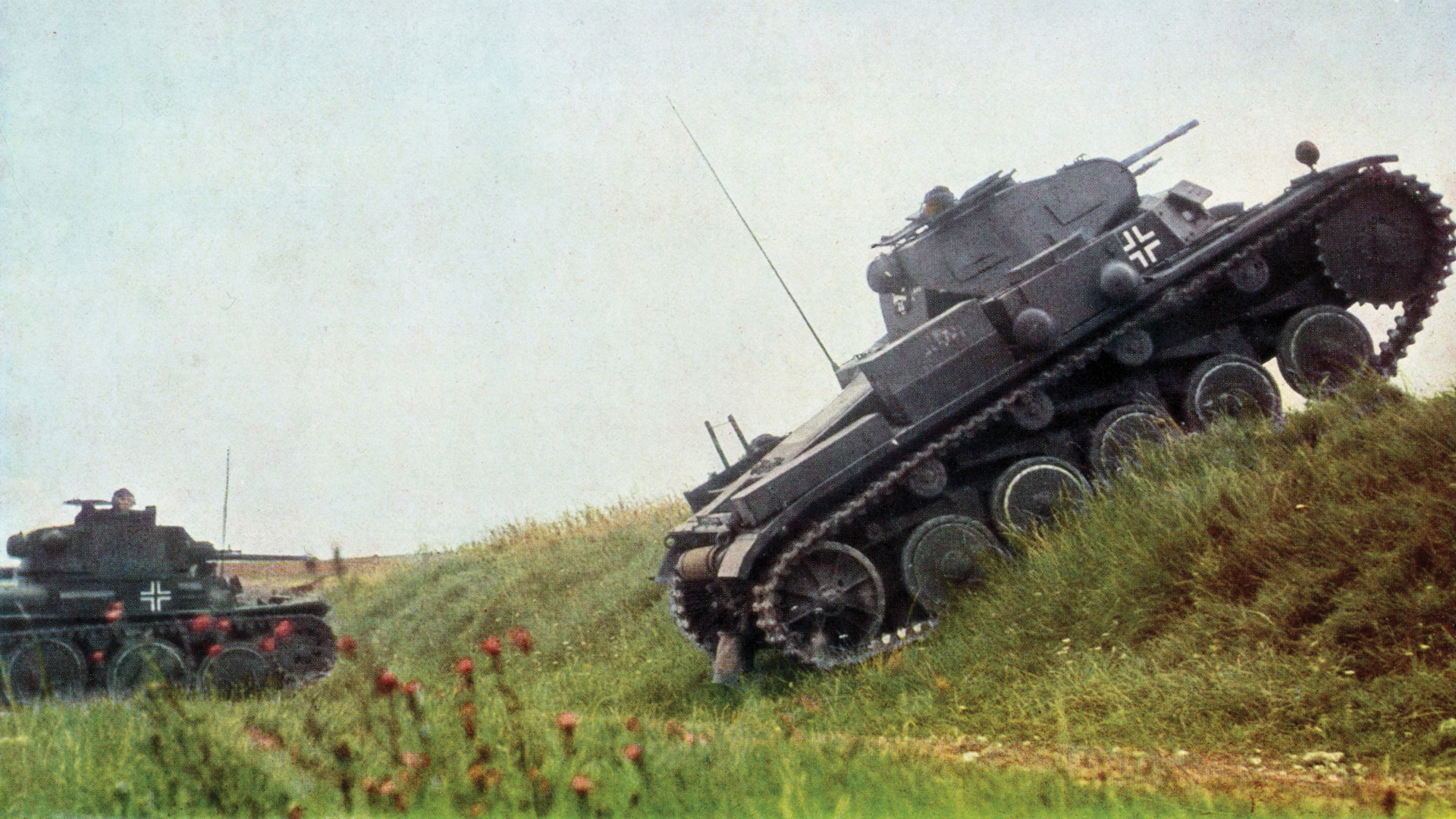

The B-24s, which were fairly large airplanes, went in over the target literally below the treetops, dropping bombs with delayed-action fuses from as low as 50 feet above the ground. The bombers came in below the flak towers that had been erected to defend the oil-refining installations, and Ben and the other gunners used their .50-caliber machine guns to shoot up the towers. American and German rounds hit gasoline storage tanks on the perimeters of the refineries, setting fires that sent thick black smoke hundreds of feet into the air. After hitting the target, the Liberator crews fought their way to the safety of the Mediterranean.

Some historians have written that the mission, which had been renamed Tidal Wave, was a disaster, although such is not really the case. Losses were heavy, although not quite as high as those suffered by B-17 groups on missions into Germany while the B-24s were in Africa. It was a spectacular and dramatic mission that ranks among the most daring of World War II.

For the first and only time in the war in the European Theater, heavy bomber crews were literally eye to eye with the German antiaircraft gunners who feverishly fought to knock them out of the sky. Of 178 Liberators that took off from Benghazi, 54 never came back. A total of 532 airmen were reported killed or missing after the mission. The 93rd suffered its highest losses of the war, with 11 B-24s and their crews shot down over the target.

Of the nine crews from Ben’s squadron who went on the mission, only two made it back to Benghazi that night. One of the crews lost over Ploesti was commanded by Colonel Baker. He and his copilot, Major John Jerstad, were both awarded the Medal of Honor, two of the five that were awarded for the mission. Everyone who went on the mission received a Distinguished Flying Cross.

Thirty Combat Missions

Ben’s group did not return to England immediately after the terrible mission, but remained in North Africa for several more weeks. After a two-week downtime to give the mechanics time to repair battle damage and replace worn-out engines, the Eighth and Ninth Air Force B-24s were sent on another dangerous mission against the aircraft manufacturing facilities at Weiner Neustadt in Austria, the third most heavily defended target in Europe.

Fortunately for Ben and the other members of the 93rd, they were part of one of the best-trained and most disciplined heavy bomber groups in the Eighth Air Force. Although the 93rd was one of the first heavy bomber groups to enter combat and was credited with flying the most missions as a group, it also suffered the lowest loss rate of any of the heavy bomber groups that were in combat during the dangerous time from 1942 to the spring of 1944 when losses began to decline. The 93rd reported only 100 B-24s missing during the entire war, and 11 of those were lost on the Ploesti mission.

The combat discipline of the men of the 93rd is also reflected in the low number of enemy planes claimed by Ben and his fellow gunners. While gunners in other groups made wildly exaggerated claims, 93rd gunners reported what they saw, not what they imagined.

The Ploesti mission took a heavy toll on the morale of the men in the B-24 groups, and Ben Kuroki was affected. He was suffering from what medics called “combat fatigue” as the intense combat took its toll on his health. He would often lurch in his bunk and cry out in his sleep. Ben had flown the required 25 missions that allowed Eighth Air Force crew members to return home, but he volunteered along with the rest of his crew to fly five more. His buddies said he was out of his mind, but he felt that as a Japanese American he had something to prove. He proved it.

Ben flew five more missions, bringing his total to 30, and he was almost killed on his last one. He was now flying with Lieutenant Homer Moran, a full-blooded Sioux from South Dakota, who had previously been the copilot on Epting’s crew but had gotten a crew of his own. They were over the target at Münster, Germany, when a piece of flak took out the side of Ben’s turret, with him inside. Fortunately, he was unscathed.

Kuroki’s Return Home: Prejudice and Public Appearances

Technical Sergeant Ben Kuroki returned to the United States as a hero and was written up in the newspapers as one. He went to Santa Monica, California, for R&R at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, and learned that he was the first Japanese American to return to California since President Roosevelt had signed the internment order. Time magazine featured an article about him, as did the New York Times. Stories about him appeared in newspapers all over the country, and his photograph was frequently featured. Journalists sought him out for interviews, for both the print and broadcast media.

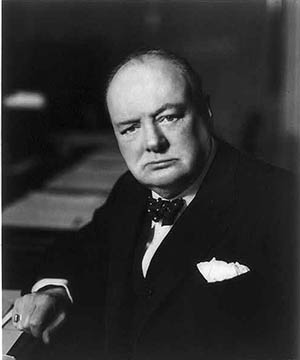

He also faced prejudice again. He was supposed to make an appearance on the Ginny Sims Show, but a female producer cancelled his appearance after taking him and two other GIs to dinner at the Brown Derby. Ben wanted to cancel an appearance before San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club himself when newspapers owned by wealthy media magnate Randolph Hearst ran headlines that said “Jap to Address S.F. Club.” He was forced to appear by the Army Air Forces public relations officer because all of the arrangements had been made. It was fortunate for Ben that he made the appearance because it changed his life.

Kuroki appeared at the Commonwealth Club on February 4, 1944. News of the Bataan Death March had just been released to the public, and Ben felt he could see hatred in the audience’s eyes. He probably was not wrong. But by the time he concluded his 40-minute address, Ben had won over the audience of business and professional men. He received a 10-minute standing ovation and was recalled to the podium twice. He so impressed the audience that his speech has been credited as the turning point in the attitude of California’s citizens toward Japanese Americans. His address was broadcast by shortwave radio to Japan. The Chicago Tribune ran an article about Ben beside an article about the Bataan Death March.

As the first Japanese American hero of the war, Ben was seen as the logical candidate to visit the internment camps where the people from the West Coast had been moved and to encourage young Nisei to volunteer for Army service or accept the draft. Several all-Japanese combat units were being formed, and the Army was actively seeking recruits from the camps and filling the ranks with draftees. Rising opposition to the draft was breaking out in the internment camps on the grounds that the internees’ constitutional rights had been violated. Although he was greeted as a hero by most of the internees, he was confronted by dissidents, some of whom despised him.

Ben was upset by the appearances. He found people of his own ancestry being guarded by armed men wearing the same uniform as he. It was not an experience he relished, even though most of the internees greeted him as their personal hero. At one camp he was greeted by a Jeep filled with flowers, and “Auld Lang Syne” was sung as he was leaving the camp at Heart Mountain. Occasionally he still experienced prejudice. A man refused to ride in a cab with him in Denver, slamming the door of the cab and shouting, “I don’t want to ride with no lousy Jap” even though Ben was in full uniform with wings and a chest full of combat ribbons, including the Distinguished Flying Cross.

“The Most Honorable Sad Saki”

After his public relations tour ended, Ben reported to Salina, Kansas. He had volunteered for a second combat tour, only this time he wanted to go to the Pacific. He went to Harvard, Nebraska, where a heavy bomber outfit was preparing for combat duty with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber. Ben was eager to fly aboard the B-29 and to fly missions against his ancestral homeland.

He was shocked to learn that War Department regulations prohibited the assignment of Japanese Americans to B-29s. Ben was no longer as stoic as he had been as a recruit, and he took advantage of his notoriety to press for a change in the policy. He solicited letters and telegrams from people he had met at the Commonwealth Club, and several prominent people contacted the War Department and the Army Air Forces on his behalf. He was allowed to continue B-29 training with the crew commanded by Lieutenant James Jenkins, but the War Department still refused to allow him to go to the Pacific. As Jenkins’s crew was preparing to depart for the Pacific, Kuroki was yanked from the airplane by federal agents, one of whom had disguised himself as a newspaper reporter sent to interview him.

Ben went looking for Nebraska Congressman Carl Curtis and found him at a lodge meeting in Minden. Ben had violated the Articles of War by contacting his congressman, but the two went looking for a telegraph station. Curtis sent wires to Secretary of the Army Henry L. Stimson and Generals George C. Marshall, President Roosevelt’s chief military adviser, and Henry H. Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces.

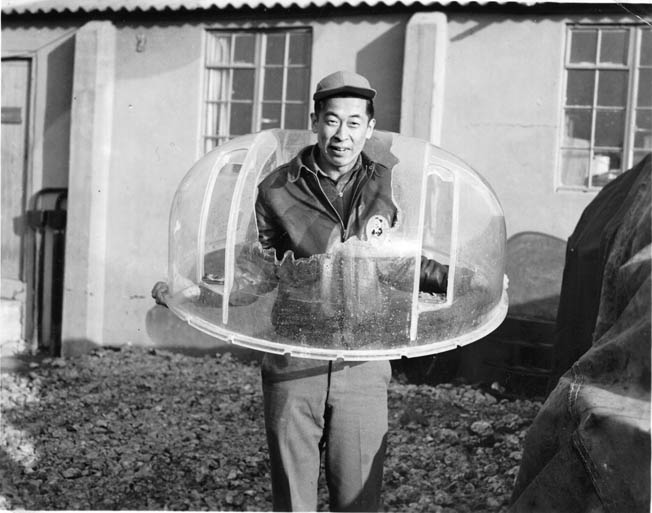

The next morning Ben received a message from Stimson that he was granting a waiver of the War Department regulations, stating that because of his previous combat record he would be allowed to remain with his crew. A few days later Ben waved from the tail turret window as Jenkins taxied out to take off in a new B-29 with the name The Most Honorable Sad Saki gleaming on the side in fresh paint.

Jenkins and his crew were assigned to the 505th Bombardment Group’s 484th Bombardment Squadron on Tinian, a tiny island in the Marianas from which B-29s were flying missions against Japan. Although Ben felt comfortable with most of the men in the squadron, his ancestry presented new problems because there were still Japanese stragglers on the island who would sneak into the camp at night looking for something to eat. Since GIs were known for being trigger happy, Ben was forced to remain in his tent at night, not even going to the latrine.

Jenkins insisted that Kuroki wear a helmet and dark glasses on the ground and that he never go anywhere alone to avoid being mistaken for a Japanese straggler. Even on trips to the mess hall, he was surrounded by other members of his crew and squadron mates. They often kidded that he owed them protection pay. Ben kidded back, saying that if they were ever shot down he would find fish heads and rice for them to eat.

Night Attacks and Napalm

The first mission against Japan from the Marianas was flown in late November 1944, while the men of the 505th were processing for the movement from their training base at Hershey, Nebraska, to the Pacific. The original missions were daylight precision bombing, but the results were far less than had been expected. Jenkins’s crew had just began flying missions when Maj. Gen. Curtis Lemay arrived to take command of B-29 operations and soon switched to nighttime attacks on Japanese cities. After the 505th arrived, the group flew a series of training missions followed by milk runs over Iwo Jima, where Marines were engaged in a fierce battle with the Japanese defenders. The group’s first mission against Japan was on February 4, 1945.

Ben Kuroki’s first combat tour had been in the B-24, which was a modern airplane when it was designed in 1940 but, with open windows, could be a miserable environment at high altitude. The B-29 was a major change. It had been designed with very long-range missions in mind and featured a shirtsleeve environment as the crew compartments were pressurized and heated, which relieved crewmen of wearing heavy sheepskin flying suits.

Initial B-29 operations over Japan met surprisingly little resistance. The Japanese had yet to organize their air defense forces, and the fighter force was much smaller than Allied intelligence estimates indicated. The B-29 was a much faster airplane than the B-17s and B-24s that preceded it, and most Japanese fighters had a hard time intercepting it. The Japanese air defenses were also hampered by a lack of skilled pilots. Most of the men who had proven so adversarial during the opening months of the war were long since dead.

In March, General LeMay ordered a change in tactics that had been suggested by Twentieth Air Force staff in Washington, D.C. For some time, the Twentieth staff had been pressing for a switch to night attacks using incendiary bombs and napalm, but General Haywood Hansel, LeMay’s predecessor, was a strong advocate of daylight precision bombing and had resisted the change—to the detriment of his future in the Pacific.

LeMay knew better than to resist “suggestions” from Washington and planned a night firebombing mission against Tokyo. He also ordered changes in combat tactics. Instead of dropping their bombs from high altitudes, the B-29s would come over the target at comparatively low altitudes in the 10,000-foot range. LeMay also ordered the removal of most of the ammunition from the guns, and all of the gunners except the tail gunner were left behind in order to save weight and increase bomb capacity.

As the tail gunner on his crew, Ben was on the mission. He later reported that for more than an hour after Sad Saki left the target he could see a fire-reddened sky. The raid was the most destructive in military history, and the young Nisei felt uneasy as he watched the fires that he knew were causing thousands, including women and children, to perish in the smoke and flames.

Ben Kuroki flew 28 missions in B-29s and had the distinction of being the only Japanese American to fly missions over Japan. Still, racism continued to cause problems. When members of his crew were presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross, Ben inexplicably was not included in the ceremony but was told to remain in the barracks even though he had been awarded an oak leaf cluster to the DFC he had been awarded for the mission over Ploesti.

The worst example of racism Ben encountered took place just before the end of the war when a drunken private from New York burst into his barracks shouting, “Tojo and Kuroki —damned Japs.” Ben immediately responded to the insult, telling the soldier, “You can call Tojo a damned Jap, but don’t call me one.”

The other man was a lot bigger than Ben, but even worse, he had a knife. He pulled it and slashed at Ben’s head, leaving a gushing wound that put him in the hospital. He was still there when the war ended. But he was fortunate; Ben probably would have been killed had not Sergeant Russell Olsen, a B-29 flight engineer, stepped in and taken the knife. The attacker was court-martialed and spent six months in the stockade at hard labor.

The Only Japanese American Air Hero of the War

The war ended before Ben got out of the hospital, and he missed going back home with his crew. Instead, he went back to the United States on a troop ship, taking 21 days for the journey that would have only been a couple of days in a B-29. Once again Ben was treated as a hero when he arrived home and was scheduled for a series of public appearances. He was invited to speak at the New York Herald-Tribune’s annual forum and was seated on the platform next to General Jonathan Wainwright, who had just been rescued from a Japanese prison camp in Manchuria.

Also on the platform were Generals George Marshall and Claire Chennault of Flying Tiger fame. Kuroki, a technical sergeant, was seated between Marshall and Wainwright. After Ben’s speech, Wainwright jumped up and grabbed Ben’s hand. The remarks Ben made that day were published in Readers Digest. As the only Japanese American air hero of the war, Ben was in demand as a lecturer, but he was tired of the war and talking about it, so he sought to return to civilian life.

Using the GI Bill, he enrolled in journalism school at the University of Nebraska, then went into the newspaper business. After 10 years in Nebraska, he sold a newspaper he owned and moved to California to start a new career as a reporter, then as editor of a major newspaper until his retirement in 1984.

Ben became active with the reunions of the 93rd Bombardment Group, and some of his fellow veterans undertook a campaign to convince the Army to award him a higher decoration than the two DFCs he received during the war. The campaign was successful, and in August 2005 he was presented the Distinguished Service Medal, the third-highest award a military member can receive. The medal was presented by President George W. Bush in a ceremony at the White House.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments