By Chuck Lyons

In the autumn of 1621, Massasoit, a sachem (chief) of the Pokanoket and Wampanoag tribes, entered American legend when he and some his people joined the Pilgrim harvest celebration that would later be called the first Thanksgiving. A friend of the Mayflower colonists from the beginning, Massasoit had helped the struggling settlement get established in the New World and later saved the settlers from starvation more than once. He arrived at the celebration with a gift of five freshly killed deer.

For the next 40 years, relations between European settlers and the Native American inhabitants of the area were generally peaceful, but underlying the peace were tensions that had existed since the beginning of English settlement. As the colonists took hold and their population grew, these tensions increased. The personal bonds that had united the first settlers and the local Indians disappeared as the first colonists and their original Indian allies died off. With beaver and other fur-bearing animals being hunted out, the Indians grew more and more dependent on European trade items, and soon all the Indians had left to sell was their land. The Indians began to feel squeezed out of their traditional hunting and farming areas. Meanwhile, Puritan attempts to convert the Indians to their own rock-ribbed brand of Christianity also caused tensions between the two peoples.

New Leadership, New Tensions

In 1662, Massasoit died and leadership of the tribe passed to his son Wamsutta, called Alexander by the settlers. Perhaps sensing that trouble was in the offing, Massasoit before his death had taken his two sons, Wamsutta and Metacom, to the home of a Pilgrim neighbor and publicly affirmed his hope that there might be love and amity after his death between his sons and the settlers. Such hope was not to be realized.

In that same year, spurred by reports that Wamsutta was selling Indian land to Rhode Island in violation of a Plymouth Colony statute that required all sales of Indian land to be approved by the court, colonial forces seized Wamsutta and took him at gunpoint to the town of Plymouth to be questioned. While in Plymouth, Wamsutta suddenly became ill. Treated by an English physician at the home of Governor Josiah Winslow, Wamsutta died a few days later, after returning to his village. The probable cause of Wamsutta’s death was appendicitis, possibly exacerbated by the powerful purgatives administered by the physician, but the chief’s people believed that he had been poisoned by the colonists.

Wamsutta was succeeded by his brother Metacom, known as King Philip, grand sachem of the Pokanokets and Wampanoags. Philip had always distrusted the settlers, and his distrust had been heightened by the mysterious death of his brother. He began to curry favor with other tribes in the region to form alliances for the war he felt was inevitably coming against the settlers. In this tense atmosphere, all it took was one spark to kindle a conflagration.

The Murder of John Sassamon

Such a spark was not long in coming. A Christianized Indian and Harvard College graduate, John Sassamon, was a translator and adviser to King Philip, as well being the husband of Philip’s sister. In January 1675, Sassamon was also working for the missionary John Eliot. Sassamon was well aware of Philip’s scheming and, after struggling with his mixed allegiances, he told Governor Winslow about Philip’s outreach to other New England tribes and warned of potential attacks on colonial settlements.

Shortly afterward, Sassamon’s murdered body was discovered beneath the ice in Assawompset Pond, near Lakeville, Massachusetts. An investigation was begun, and in March Philip appeared at Plymouth to answer questions about his in-law’s death. He strongly denied having taken any part in the killing and protested that the murder—if indeed it was murder and not an accident—was an internal Indian affair and not the business of the colony.

In the end, three Wampanoags, including Philip’s chief counselor, Tobias, were arrested for the murder and tried before a jury of 12 colonists and six “praying Indians,” or Christian converts. Based on the testimony of an alleged eyewitness to the killing, the Wampanoags were unanimously found guilty. Two were hanged on June 8, and the third, Tobias’s son, Wampapaquan, was shot and killed a month later. Philip and his people were outraged at the verdict and the hasty executions, believing them to be a miscarriage of justice and an unjustifiable white interference into Indian matters.

King Philip on the War Path

With his warriors eager for revenge and pressuring him to act, Philip felt propelled toward war a year earlier than he had planned. In all, Philip had only a few hundred ill-equipped warriors and considerably less gunpowder than he had planned on stockpiling, but he also knew that he could not hold back his young men much longer. Some warriors had already begun pilfering cattle and burning abandoned houses, although no colonists had yet been injured.

Meanwhile, aware of a growing threat, the Plymouth and Massachusetts militia gathered at Swansea, north of Philip’s Mount Hope village, along the Rhode Island-Massachusetts line. Winslow, who believed the current Indian problems were a sign of God’s displeasure, declared June 24 a day of prayer and fasting in the colony. The settlers, he wrote, should “humble ourselves before the Lord for all those sins whereby we have provoked our good God sadly to interrupt our peace and comfort.”

On that same day, Philip’s warriors struck—possibly without Philip’s knowledge—killing 10 settlers in Swansea, some of whom were attacked on their way home from religious services. Whether or not he wanted it yet, Philip had gotten his war. Over the next few days, the Indians grew bold enough to attack the gathering militia, killing two men sent to fetch water and two apparently unwary sentries.

“God and his Protecting Providence”

Scattered skirmishing followed, and the combined Massachusetts and Plymouth force marched to Mount Hope, finding along the way several burned farms and homes and eight English bodies. At Kickimuit they discovered the abandoned settlement burned and, even worse for the good Puritans, pages from a torn-up Bible blowing across the empty village square. At Mount Hope itself, they found that the Indians had gone. While the Plymouth militia stayed at Mount Hope, fortifying the site and uprooting all the corn growing in fields around the village, the Massachusetts men continued crossing by ferry to the eastern side of the Narragansett Bay. They were looking not just for Philip’s force, but for any other Indians they could find.

Led by Benjamin Church, a carpenter and settler from Bristol, Rhode Island, the force of 18 men could see Indian signs as they traveled south alongside the bay. Eventually, they came across two Indians working in a newly cultivated field of peas. The Indians began to run and the New England men chased them into the woods—and straight into an ambush. As the Indians fired on them, Church ordered his men to retreat and take shelter behind a fence. The field bordered the Sakonnet River, and when more and more Indians poured out of the woods, Church realized that they were attempting to surround the English before they could reach the water. Church ordered the militia to cross the field and take position behind a stone wall at the water’s edge. Meanwhile, several hundred Indians surrounded the party, pouring in shots while the colonists used rocks, fallen wood, and whatever else they could find to reinforce their position.

Church’s men were running out of ammunition when they spotted a sloop sailing toward them from Aquidneck Island. As the sloop entered the river and approached the beleaguered colonists, the Indians turned their fire on it, and the sloop retreated to the island. Throughout the day, the Massachusetts men were able to hold their position, and as night began falling they saw another sloop heading out from an island a few miles upriver. That sloop, captained by Roger Goulding, anchored near the trapped men and floated a canoe into the shore. It took 10 trips in the small canoe to extricate everyone, and Church was the last to leave the shore. Remarkably, the colonists escaped without a single casualty, and throughout his life Church looked back on what became known as the Pease Field Fight as a shining example of “God and his protecting Providence.”

More Tribes, More Bloodshed

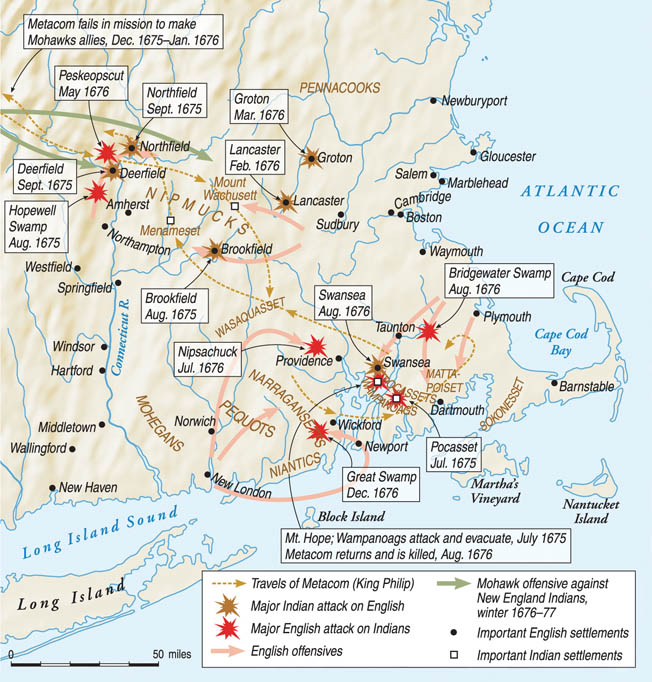

The war quickly escalated, and other New England tribes joined the raiding. In July, the Massachusetts and Plymouth militia pursued Philip and his tribesmen into the Pocasset Swamp on the east side of Mount Hope Bay. While the militia force surrounded the swamp, believing they had Philip and his men trapped, Indian attacks spread throughout other parts of the colonies. Mendon, 20 miles from Boston, was attacked and six people were killed. Dartmouth and Middleborough, Massachusetts, were burned. Then, in late July, came word that Philip and his men had been spotted almost 20 miles to the west. They had slipped out of the colonists’ trap.

Philip and his remaining warriors fled west and north, engaging in a fight with English volunteers and a group of about 50 Mohegan Indians who had joined the colonists at a spot called Nipsachuck, north of Providence. Before escaping into a nearby swamp, Philip lost 23 warriors. The colonists, who had lost two men, waited until the following morning to pursue, by which time Philip and his dwindling force again had slipped away, heading north and eventually taking refuge at a Nipmuck village near New Braintree, Massachusetts. By this time, Philip’s original force of 250 fighting men was down to 40. He urged the sheltering Nipmucks to join him in the war.

Increasingly, the war took on a life of its own as more New England tribes were sucked into the fray. In August, the Nipmucks attacked Brookfield in central Massachusetts, burning the town and laying siege to the home of Sergeant John Ayers, where Brookfield’s terrified settlers had huddled. For two days, the 80 settlers held out until they were rescued by 50 troopers. The Nipmucks scattered and then reassembled on August 22 to attack Lancaster in the Connecticut River Valley. On September 3, a colonial force of 36 men sent to evacuate Northfield in northern Massachusetts was ambushed, and 21 of the colonists were killed.

An Official Declaration of War

On September 9, 1675, the colonies officially declared war on the Indian tribes, and on September 17 a day of humiliation was held in Boston, with residents urged to refrain from “intolerable pride in clothes and hair and the toleration of so many taverns.” That same day, Captain Thomas Lathrop was escorting 79 people from the town of Deerfield on the Connecticut River when, as they prepared to ford a small stream, they were attacked by a war party of Indians. Fifty-seven of the settlers were killed and the waters of the creek, thereafter known as Bloody Brook, ran red. In October, Indians attacked and burned Springfield, Massachusetts, and there were also attacks on settlements along the Maine coast. Meanwhile, Philip spent much of the winter camped along the Massachusetts-Vermont border with his few remaining warriors.

The war took on a racial dimension. New England’s Indians—warlike or peaceable—were demonized, and the colonists turned their gaze south on the Narragansetts, the largest tribe in the region and one that was ostensibly neutral. The Narragansetts were known to be sheltering Wampanoag women and children, and Narragansett warriors reportedly had been seen taking part in some of the raids. The united colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth collected 1,000 soldiers and 150 allied Pequot and Mohegan Indians, and on December 8 they marched west and south seeking the Narragansetts.

The March on the Narragansetts

In Rhode Island, the force captured an Indian named Peter, who because of a disagreement with Narragansett sachems was willing to talk with the colonists. He told them the Narragansetts had about 3,000 fighting men, most of whom were holed up with their women and children in a large swamp immediately southwest. The cold winter had frozen everything solid, including the swamp, but with Peter as a guide the expedition set out to engage the Indians. On December 15, the force learned that Jireh Bull’s garrison had been attacked and burned and another 15 colonists killed. Winslow, who was heading the expedition, had planned to use the Bull garrison as a point from which to rearm his men and launch an attack. They were now dangerously low on supplies.

The following day was a Sunday, and Winslow, despite his Puritan scruples, felt compelled to attack because of his army’s lack of provisions. It had snowed during the night, and by 5 am there was already three feet of snow on the ground. The colonists marched for eight hours before coming to the swamp, where the concealed Indians began to fire on them from the thick brush and trees. Winslow’s party entered the swamp, driving the Indians before them, and came on a large wooden fort situated on a five-acre island. The enclosure, containing some 500 wigwams, was surrounded by a palisade of upright tree trunks and a 16-foot-thick barrier of clay and brush. At the corners were primitive watchtowers from which the Indians could fire down on attackers, and a massive tree trunk spanned a moat, now frozen, that appeared to provide the only access to the fort. Anyone trying to cross it to the fort would be picked off by Indians firing from the watchtowers.

Searching the perimeter of the fort, the colonists discovered a section that had been left unfinished. Tree trunks had been laid horizontally up to a height of about four feet. The opening was wide enough to allow several attackers to scramble over the wall. The colonists spread out and began to pour fire into the fort while companies led by Captains Isaac Johnson and Nathaniel Davenport stormed through the opening. Johnson and Davenport were killed almost instantly, and the Indian fire was so intense that the men who survived the initial charge were pinned down, waiting for reinforcements. Two more units assaulted the opening and were also pinned down. Major Samuel Appleton and Captain James Oliver then formed their men into an attack column, rather than the broad front the other units had tried, and were able to push past the pinned-down men, break through the opening, and outflank the Indians on the left.

Connecticut troops rushed into the breach and met a devastating fire from the watchtower that killed four of the five commanding officers. Meanwhile, Captain Church, the same man who had led the English at the Pease Field Fight, gathered 30 Plymouth Colony volunteers and stormed the opening. This time the colonists were able to break into the fort. Between 300 and 400 English soldiers jammed into the enclosure, while Church sent back word to Winslow to cease firing. Church’s men inside the fort were being hit by friendly fire from outside.

The Indians, meanwhile, were running out of gunpowder and were abandoning the fort to take up positions in the trees beyond. Church, realizing that the fort was effectively taken, led his men out of the enclosure, following a “broad, bloody track” where the Indians had dragged their dead and wounded. Moving quietly through the woods, the colonists came upon a group of Narragansetts preparing to fire a volley into the fort. Whispering to his men to hold their fire, Church ordered them to wait until the Indians rose in a body. The colonists fired first, giving the Indians “such an unexpected clap on their backs” that the tribesmen scattered in confusion, some even running back into the fort for cover.

The Great Swamp Fight

Church and his men pursued, and Church suffered a serious wound in the thigh. By this time, the Indians had run out of gunpowder and were firing at the colonists with bows and arrows. Church’s men, confused without his leadership, abandoned their attack on the fort and pulled Church to safety. By now it was starting to get dark, and the colonists began setting fire to the wigwams, which still sheltered Indian women and children, as well as provisions that colonists could sorely have used, since they were almost out of food themselves and had 16 frigid miles to cover before they would reach another English settlement. Church urged Winslow to use the fort for shelter rather than destroy it, but Winslow rebuffed his suggestion as fire swept through the five-acre compound.

As the dusk deepened, the colonists marched away from the burning fort, 800 men carrying more than 200 of their wounded and dead comrades. For many of the men, it was the worst night of their lives. They had spent the previous night sleeping in the snow in an open field and then had marched for eight hours, fought for three, and were now marching again. The first hungry, frozen, and exhausted units finally arrived at the safety of the Smith garrison about 2 am, while Winslow and his men became lost and did not arrive for another five hours.

Twenty-two of the wounded colonists had died during the march; another six died a few days later. In all some 20 percent of the force, about 200 men, had been killed or wounded at what was to become known as the Great Swamp Fight. Estimates of Indian losses ranged from 350 to 600 men, women, and children. The Indians who survived the raid made their way north to join the Nipmucks. The colonial army pursued them briefly, but short of provisions, plagued by desertions, and riddled with disease, it finally disbanded at Marlborough on February 5.

Philip Provokes the Mohawks

Philip headed west and camped near the Hudson River where, among other advantages, he had easier contact with the French to the north. He had been in contact with them earlier and had been promised supplies and at least 300 Canadian Indian reinforcements. By February 1676, Philip had collected a large force of Indians, possibly as many as 2,100, and was trying to bring the powerful Mohawks into his alliance as well. In order to recruit the Mohawks, Philip resorted to trickery, having a small group of Mohawks killed and then blaming the murders on the colonists. One of the Mohawks escaped the ambush, however, and revealed Philip’s involvement in the scheme. In retaliation, the Mohawks attacked Philip’s camp and sent the few remaining survivors hastening back to New England.

The Mohawk attack all but eliminated the possibility of help from the French. The tide of the war, which had now turned into a battle of attrition, had swung in favor of the colonists. Indian confidence was shaken, and cracks in the intertribal alliance were beginning to show. More importantly, Indian food supplies were running low and planting season was fast approaching. The Indians needed to take decisive action soon or else they would starve to death. The colonists could depend on periodic deliveries of supplies from England, but the Indians were left to their own devices while their traditional fields and hunting grounds were under attack by roving bands of colonists.

Philip’s War Unravels

By this time, Philip had become largely irrelevant to the war he had ignited, and other tribes that had been drawn into the conflict continued raiding settlements from Connecticut to Maine. On March 26, a colonial force was ambushed along the Blackstone River, north of Providence, and 55 English and 10 allied Indians were killed. On March 29, Providence itself was attacked and burned.

In April, a Connecticut army fell upon the same 1,500-man Indian force that had destroyed the colonial troops at the Blackstone and burned Providence. Canonchet, the Narragansett sachem who was leading the Indian force, was captured and executed by firing squad. Colonial forces, combined with Christian Indians, Mohegans, and Pequots, enjoyed growing success against the raiders. In May, Massachusetts’s militia and volunteers attacked a large fishing camp at Peskeopscut, near Turner Falls, Massachusetts, and killed between 100 and 200 Indians. Forty militiamen and the group’s leader, Captain William Turner, were also killed. By summer, Philip’s oldest allies began deserting him. Over 400 surrendered to the colonists, and Philip himself went into hiding.

In June, Church was able to form an alliance with the Sakonnet, who had broken with Philip and returned to their traditional Rhode Island home. The Nipmucks, with whom Philip had been staying, also decided to sue for peace, and Philip fled back to Plymouth. Church, leading an independent 24-man force, had begun to adopt Indian fighting techniques—spreading his men out loosely in the woods, moving silently, and never leaving a swamp by the same route he had entered it. As he began to have victories, his force grew from white volunteers and captured Indians he convinced to join him.

To Kill a King

At the end of July, Church and his men skirmished briefly with Indians under Philip’s command at Bridgewater, near Plymouth, and then pursued the fleeing Indians west, taking 173 prisoners. Finally, in August, Church was approached by an Indian who said his brother had been killed by Philip; he proposed to lead the colonists to the sachem’s hiding place. Following the guide, Church and his men approached Philip’s camp in the Assowamet Swamp about midnight and surrounded the swamp. At dawn on August 12 they attacked. Philip, fleeing the camp, was killed by one of Church’s pickets, an Indian named John Alderman, who shot an Indian running past him, unaware that it was Philip himself.

Philip’s body was dragged into the English camp, where it was displayed like a trophy from a hunt. Philip, said Church, was “a doleful, great, naked, dirty beast.” Because Philip had left many of his white victims unburied and rotting in the sun, Church decreed that “not one of his bones should be buried.” Instead, he had an old Indian executioner chop Philip’s body into four pieces and cut off his head. One hand was given to Alderman, the man who had brought down the chief. Alderman preserved his grisly trophy in a bucket of rum. Philip’s head was taken to Plymouth, where it was mounted on a tall stockade pole for public viewing. Years later, Massachusetts clergyman Cotton Mather yanked Philip’s jawbone from the desiccated skull as a final insult to “this bloody and crafty wretch.” A number of Indian captives were tried and executed, while others, including Philip’s son, were transported to Bermuda and sold as slaves. The war was effectively over.

Devastation for the Tribes, an Identity for the Colonists

More than 600 colonists had been killed, a staggering number. In World War II, by way of comparison, the United States lost slightly less than 1 percent of its adult male population. In the Civil War, between 4 and 5 percent perished. In King Philip’s War, 8 percent of adult males were lost. For the Indians, casualty rates were even worse. Out of an estimated prewar population of 20,000, an estimated 2,000 Indians were killed during the war; another 3,000 died from disease or starvation. An additional 1,000 were shipped out of New England as slaves. Of those who survived, 2,000 fled to Canada or the West.

In addition to human losses, the war ultimately cost the colonies 100,000 pounds, at a time when the average family earned about 20 pounds a year. Twelve towns were all but completely destroyed. But the victorious New England colonies were now open to increased settlement without concern for Native American interference. Indian raids continued sporadically for the next 70 years—often egged on by the French—until such attacks ended following the French and Indian War.

King Philip’s War, like all wars, had unintended consequences. The most long-lasting, perhaps, was the forging of a new group identity among the New England settlers, who began to think of themselves not as Englishmen but as Americans. It was a change that would become fixed and consecrated by fire a century later at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. By forcing the colonists to fight for their lives, King Philip ironically had taught them how to do so. It was not a lesson he relished teaching.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments