By Eric Niderost

Lieutenant John P. Lucas of the 13th U.S. Cavalry was sound asleep in a small adobe shack in Columbus, New Mexico, on the night of March 9, 1916, when he was abruptly awakened by the unmistakable sounds of men and horses passing outside his window. It was 4:30 am in the small desert town three miles from the Mexican border. Mexico was in the throes of a bloody revolution, and the 13th Cavalry was there to make sure that the violence did not spill over into the United States.

Lucas quickly rose, stumbling in the darkness, and peered through the window into the inky void. His sleepy eyes confirmed what he had heard—a large number of horsemen were coming into town. It was still dark, but Lucas caught sight of one of the horsemen, who was wearing a black sombrero. There was no doubt in the lieutenant’s mind that the intruders were Pancho Villa’s men, and that Columbus was under attack.

The lieutenant groped blindly for his pistol, moving into the middle of the room facing the door. Adrenaline coursing through his veins, Lucas fully expected the approaching Villistas to break in and finish him off. He was determined not to go down without a fight. With luck, he could take one or two with him.

A nearby commotion saved the lieutenant’s life. As the raiders approached Post No. 3, not far from the 13th Cavalry headquarters at Camp Furlong, they were challenged by the sentry on duty, Private Fred Griffin of Troop K. In answer, a Villista shot Griffin in the stomach, mortally wounding him. Staggered by the blow, Griffin raised his 1903 Model Springfield rifle and killed three raiders before dying himself.

There was now no need for secrecy. Someone in the darkness cried, “Vayanse adelante, muchachos!” In response, the raiders spurred their horses forward with shouts of “Viva Villa!” and “Muerte a los gringos!” The Columbus raid had begun. Although small in scale, the predawn raid was to loom large in the troubled history of relations between the United States and its tumultuous neighbor to the south, sparking an American military response that would nearly lead to war between the two nations.

The Mythical Pancho Villa

Pancho Villa, whose real name was Doroteo Arango, was the central figure in the drama, and the raid and subsequent events cannot be fully understood without an exploration of Villa’s character. Villa was a larger-than-life figure whose legend resonates in both countries to this day. But Villa the man is hard to separate from Villa the myth—a myth partly based on fact but also, ironically, the product of American newspapers and motion pictures.

American attitudes toward Mexico were an uneasy mixture of idealism and condescension. Bad relations between the two nations dated as far back as the 1830s and 1840s, when Texas rebelled against Mexico, instigating the Mexican War and resulting in the loss of a sizable chunk of the latter’s territory to the United States. Antagonism continued into the 20th century as a string of impotent Mexican leaders failed to bring order to their fractious nation.

In 1910, rebels led by Francisco Madero ended the 30-year-long dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz, commencing a new period of unrest and uncertainty as different political factions jockeyed for power. Three years later, General Victoriano Huerta ousted Madero in a coup, killing his rival in the process. Huerta was scant improvement over his predecessor; flagrant corruption continued to plague the country. Rebel forces rallied around charismatic leaders such as Emiliano Zapata in the south and Alvaro Obregon, Venustiano Carranza, and Pancho Villa in the north.

President William Howard Taft closely monitored the chaotic situation in Mexico, sending 16,000 troops to the border in 1911 to safeguard American citizens (and American business interests). When Woodrow Wilson succeeded Taft as president in March 1913, he refused to recognize Huerta’s government. Instead, he dispatched additional naval forces to Tampico and Veracruz to protect American interests there and prevent weapons from flooding into the country from abroad. Mexicans understandably saw Wilson’s actions as blatant meddling in their internal affairs. Anti-American hostility increased.

Tensions reached a boiling point on April 9, 1914, in Tampico, when a group of American sailors from the USS Dolphin were seized by Mexican authorities after they mistakenly entered a restricted area in search of supplies. Although an embarrassed Huerta swiftly ordered their release and issued a formal apology to the United States, Wilson reacted by sending additional naval forces to the Mexican coast to monitor the worsening situation.

Two weeks later, a German ship loaded with arms for Huerta approached Veracruz. Wilson immediately ordered Marines to occupy the port city. Some 800 American Marines and sailors stormed ashore and fought their way into the center of town. Bitter street fighting continued throughout the day, claiming 17 American lives and another 61 wounded, while nearly 200 defenders were killed, further inflaming hostility toward the United States throughout Mexico and the rest of Latin America.

The Carranza Regime Takes Power

In July 1914, Huerta resigned. Four months later, Wilson pulled his forces out of Veracruz and threw his support behind the opposition Carranza government. But Carranza faced continued opposition from his top subordinates—Zapata, Obregon, and Pancho Villa. Zapata and Villa soon broke with each other over the proper conduct of the war, and by 1915, Villa and Obregon were mortal enemies as well. It looked at first as though Villa, the fabled Centaur of the North, held all the cards. But Obregon threw his support behind Carranza and decisively defeated Villa at Celaya that April.

Although Carranza often filled his speeches with anti-American rhetoric, he seemed a more stable choice than the discredited bandit chief, and in October 1915 the United States officially recognized Carranza and his regime as the legitimate rulers of Mexico. The Wilson administration materially aided Carranza by allowing Mexican troops to use American railroads and cross through U.S. territory to reinforce the government outpost at Agua Prieta. The additional reinforcements tipped the balance in favor of government forces. Villa launched three waves of attacks on Agua Prieta, only to be repulsed each time with heavy losses.

The once-proud Division of the North was virtually destroyed. Most survivors either surrendered or simply drifted home. Pancho Villa still remained at large, hiding in the hills with a few hundred hard-core followers. When Villa heard that Wilson had recognized Carranza, he flew into a towering rage, swearing revenge. Incidents along the border increased to the point that some American hotels began advertising that their establishments were bulletproof.

American Interests on the Mexican Border

Meanwhile, American border states—particularly Texas—grew more and more alarmed at the increasing violence along their southern boundaries. Mexican bandits—some Villistas, some not—regularly crossed into the United States to rob, assault, and kill American citizens. From July 1915 to June 1916, there were some 38 such raids, resulting in the deaths of 37 Americans. In response, Americans along the border formed vigilante groups that preyed on unoffending Mexican Americans. One group shot 14 Mexican Americans and placed their bodies along the roadway as a warning. Some of the fabled Texas Rangers were also guilty of random atrocities. To stop both the border raids and the escalating violence of both sides, President Wilson and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan ordered General Frederick Funston, head of the Army’s Southern Department, to dispatch more troops to the border.

There were numerous silver and copper mines in Sonora and Chihuahua, most of them owned and operated by American concerns. These mines, crucial to the Mexican economy, had been shut down due to revolutionary violence. As a sign that they were firmly in control, Carranza and Obregon declared Sonora and Chihuahua pacified and encouraged residents and foreign workers to return. Taking them at their word, the American Smelting and Refining Company dispatched engineers to reopen the Cixi Mine in Chihuahua.

On January 9, 1916, 17 mining officials and engineers aboard a train on the Mexico North Western Railway were stopped by Villa’s men near Santa Ysabel. The bandits took the Americans off the train, lined them up, and shot them in the head one by one. One Texan feigned death, crawled into a patch of mesquite bushes, and managed to escape. News of the slaughter so enraged citizens in El Paso that Army commanders had to declare martial law to prevent American vigilantes from crossing into Mexico and extracting revenge.

Battle in the Streets of Columbus

But Villa was not done with the gringos he felt had betrayed him. He started to plan for a raid on a border town, although at first Columbus, New Mexico, was just one of many possible targets. According to some accounts, his intelligence was faulty. His spies told him Columbus had only 30 American soldiers in it—the number was closer to 350. Villa’s motives have been endlessly debated, but probably he wanted to provoke a war between the United States and Mexico that ultimately would lead to Carranza’s downfall. If his men could get their hands on some loot, weapons, and a few horses, so much the better.

Columbus was a small border town of around 350 souls, described by Lieutenant John Lucas as “a cluster of adobe houses, a hotel, a few stores and streets knee deep in sand, combined with mesquite, cactus, and rattlesnakes.” The El Paso and Southwestern Railroad ran roughly east-west along the borders of the town. Camp Furlong, the military base, was just over the tracks. Along the southwest edge of town there was a cactus-studded knoll known to locals as Cootes Hill.

Villa and his men crossed the border at about 2:30 on the morning of March 9, 1916. He divided his main force into five groups. Two groups would swing left and circle the town from the north, while a third would attack Camp Furlong from the south and west. Villa would remain in the vicinity of Cootes Hill with two reserve groups. The Villistas were confident that they had achieved the element of surprise.

Once the American sentry was shot down, however, all hell broke loose. Villa’s raiders poured into the town’s small commercial district, the sandy streets and adobe buildings echoing and reechoing with the sounds of shouting men, flailing hoofbeats, and the sharp crack of rifles. The raiders dismounted and rushed into the Commercial Hotel, where they seized several male guests, dragged them outside, and killed them without mercy. William T. Richie, proprietor of the hotel, had just enough time to hide his wife and three daughters on the top floor before the bandits headed up the stairs. Captured, he willingly went down to the first floor, no doubt relieved that his family had not been discovered. He had little time to savor his good fortune; he too was quickly gunned down.

The raiders spent much of their time breaking into shops and homes and looting everything they could lay their hands on. They set fire to a store across the street from the Commercial Hotel, and soon the hostelry itself was alight. The hotel went up like a torch, the crackling flames leaping high out of every window. The Richie women were rescued from the conflagration by a young man improbably named Jolly Gardner and a Mexican American, Juan Favela.

20,000 Rounds

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Lucas made the most of his reprieve from death. Since the Mexicans were not going to burst in, Lucas used the cover of darkness to try and make his way to Camp Furlong’s barracks. The lieutenant somehow managed to evade the raiders, but in the excitement he had failed to put on his boots. It took a month for him to remove all the burrs and thistles from the soles of his feet.

In another part of the encampment, Officer of the Day Lieutenant James C. Castleman was reading a book when the commotion started. As he came out the door, the American was confronted by a bandit aiming his rifle at him. The Mexican fired but missed, giving Castleman his opportunity. The lieutenant shot back with his .45-caliber automatic, the heavy slug blowing off a good part of the Villista’s skull.

Castleman met Sergeant Michael Fody, who had rallied the lieutenant’s F Troop. Without hesitating, Castleman led F Troop toward the town, where the situation seemed to be most critical. Lucas was also active, joining his machine-gun troop and breaking out all available weapons. The French-made Benet-Mercier machine guns, fed by 30-round stock clips, had a nasty habit of jamming at inopportune moments. Lucas and his men began firing into the darkness, the raiders’ muzzle flashes their only clue to where the enemy might be. The noise of machine guns joined the sharp crack of Springfields and the bark of Mausers. Many raiders were cut down by the machine guns, which fired some 20,000 rounds before the fight was over.

Back in the town, the invaders soon had cause to regret their arson. The burning hotel and stores lit up the area better than a probing searchlight. Rampaging raiders were silhouetted, backlit by the roaring flames, and the doughboys’ Springfields quickly dispatched dozens of Villa’s men. After about two hours, the raiders began to retreat. Major Frank Tompkins gathered some 56 men from F and H Troops, mounted up, and went off in hot pursuit, chasing his quarry 15 miles into Mexico before low ammunition forced him to call a halt to the pursuit.

The Columbus raid was over. Nine American civilians and eight soldiers lay dead. In practical terms, Villa’s raid was a fiasco for the former bandit chief. A total of 67 Villistas had been killed at Columbus. Counting the men lost during Tompkins’s pursuit, well over 100 of increasingly scarce command were dead—some estimates say as high as 200. But if Villa’s main objective was to provoke American intervention in Mexico, then he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. Woodrow Wilson could not tolerate such a brazen invasion of U.S. soil, particularly in an election year. After a flurry of diplomatic exchanges between Wilson and Carranza, the latter reluctantly agreed to permit an American incursion. The assent was ambiguous and couched in such a way that it could be repudiated quickly for domestic political reasons.

John Pershing and the “Punitive Expedition”

Not one to linger over diplomatic niceties, Wilson organized what he called the “Punitive Expedition.” The expedition would be commanded by 55-year-old Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing, a veteran officer who was well liked within the Army, but who had the reputation of being hard-nosed and efficient. He would be given two cavalry brigades and one infantry brigade to complete his mission: Nicknamed “Black Jack” Pershing after commanding the all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment, the veteran of Indian wars in the West and fighting in the Philippines quickly gained the respect of soldiers and civilians in his Texas post.

But political exigencies soon altered the goal of the mission. Originally, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker gave orders for Pershing to cross the border in pursuit of the Mexican band that had raided Columbus. But Wilson, eager to assuage the Carranza government’s concerns of a general American invasion, changed the emphasis. The Army was to enter Mexico with the sole objective of capturing Villa himself. Speaking for many, one Army officer had little confidence in the outcome. “All military men,” he said, “know that under the orders [Pershing] received he had as much chance to get Villa as to find a needle in a haystack.”

Pershing’s task was an unenviable one. The Chihuahua terrain is shrub desert, dry, desolate, and remote. Much of the desiccated, cactus- and mesquite-studded terrain is a high plateau, with altitudes upward of 5,000 feet. That makes for searing heat in the day and bone-chilling cold at night. The western part of Chihuahua is mountainous, with the jagged peaks of the Sierra Madre Occidental thrusting up to the sky like a giant’s backbone.

Even worse, there were no roads to speak of, just desert tracks that were dusty in summer and quickly became muddy quagmires when it rained. The soldiers managed to use some of the Mexican railroads, but access was deliberately limited by the Carranza government. Reliable intelligence on Villa’s whereabouts was also limited, and rumors, half-truths, and deliberate lies were rife. Most Mexicans, whatever their actual politics, resented Americans meddling in their country’s affairs. They were unwilling to cooperate.

An Army Made for Motorized Warfare

Pershing’s command was largely composed of regular Army troops, professional and inured to hardship. The First Provisional Cavalry Brigade consisted of the 11th and 13th Cavalry and a battery from the 6th Field Artillery. The Second Provisional Cavalry Brigade contained the 7th and 10th Cavalry and another battery of the 6th Artillery. The 7th and 10th were among the most famous regiments in the Army. The 7th Cavalry, or “Garry Owens,” were best remembered for Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s ill-fated fight at the Little Bighorn against the Sioux and Cheyenne in June 1876. They took their name from Custer’s favorite marching song. The 10th Cavalry came from the legendary “Buffalo Soldiers,” an all-black unit that had also gained fame in the Indian wars. The 2nd Provisional was rounded out by another battery of the 6th Artillery. The 1st Provisional Infantry Brigade was made up of soldiers of the 6th and 16th Infantry Regiments and support troops.

Pershing’s plan was simple. The main body would cross the border at Columbus, while the rest would cross at Culbertson’s Ranch, 80 miles to the west at Hachita. The columns were to converge at Casas Grandes. It was hoped that Villa would be trapped between the two units. The march to Casas Grandes was one of the fastest and most grueling in the annals of the U.S. Cavalry. Pershing’s weary command arrived at Casas Grandes at 8 pm on the evening of March 17, having traveled 68 miles in two days. The march had been an ordeal for man and beast alike. The scissoring hooves had kicked up choking clouds of alkali dust, and once the sun slipped behind the rose-colored cliffs, the temperatures dropped to near freezing,

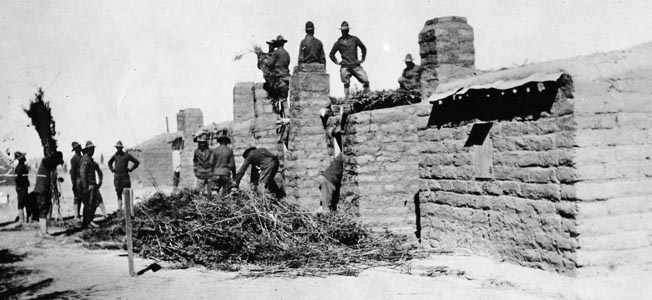

Casas Grandes and the nearby Mormon community of Colonia Dublan would serve as main bases for the punitive forces. Some supplies were sent by rail, including building materials, wood, sugar, potatoes, and onions. But some of the slack was taken up by motor transport, a new concept. Truck convoys hauled supplies over dusty, deeply rutted tracks. Some of the terrain was so rough and primitive that the expedition had to rely on the time-honored, stubborn charms of the Army mule for supply. A vehicle-maintenance base operated out of Columbus for the duration.

Pershing and Patton on the Front

Pershing, headquartered at Casas Grandes, received information that Villa was some 50 miles to the south. The bandit had escaped his net, but Pershing was still hopeful. The general dispatched three parallel columns from Colonia Dublan, hoping they would get behind Villa and cut off his escape. Once the rest of his command arrived on March 20, Pershing sent out smaller flying squadrons to scour the areas not covered by the three main columns.

In the meantime, Villa attacked a Carranza garrison at Guerrero. He took the town easily but was accidentally wounded by one of his own men. By this time, Villa was press-ganging local villagers into joining his band. It was said that the bullet that shattered Villa’s shinbone was fired by a disgruntled draftee. Whatever the case, Villa was badly wounded—but ironically, the wound proved his salvation. Villa, literally crying and cursing with pain, left Guerrero around midnight on March 29, carried in a litter and guarded by 150 followers.

At that very moment, Colonel George F. Dodd and the 7th Cavalry were heading for Guerrero. The 7th mounted up at Bachiniva, but the guide was unsure of the way. When the locals proved uncooperative, Dodd was forced to use a circuitous route that delayed his arrival. Dodd and the 7th Cavalry finally reached Guerrero at 6 am, six hours after Villa’s departure. The Americans would never again get so close to capturing their elusive foe.

Dodd still had a job to do, and he attacked at once. The 63-year-old colonel led the charge with a .45-caliber pistol in his hand. The troopers followed, spurring their horses forward in spite of the grueling all-night march over forbidding terrain. The remaining Villistas were soon on the run, retreating after 56 were killed and 35 wounded. The Americans had only five wounded and none killed.

Pershing took enormous personal risks during the campaign, often doing his own reconnaissance deep in enemy territory. His peripatetic headquarters was simple in the extreme. Staff consisted of his aide, Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr., four escort guards, three drivers, and the general’s cook, an African American named Booker. The official caravan consisted of four Dodge touring cars. Riding directly behind in broken-down Model Ts were correspondents from the New York Tribune, Chicago Tribune, and the Associated Press.

Sergeant Chicken

Villa hid out in a cave called the Cueva de Cozcomate. In great pain and unable to walk, the bandit leader stayed literally underground for two months while he recuperated. The mouth of the cave was camouflaged by branches and leaves. Relatives bought him food since no one else could be trusted with the secret. From his lair, the wounded Centaur of the North watched one day as an American cavalry patrol rode by.

Apache scouts were used on the campaign, some of them old warriors who had hunted down Geronimo in the 1880s. One of the most outstanding Apache scouts went by the unlikely name of Sergeant Chicken. His real name was Eskehwadestah, almost unpronounceable to whites. The Indians served the Punitive Expedition with relish since Apache-Mexican enmity dated back to the 18th century.

Under Fire from the Mexican Government

Villa had split his command into four groups, scattering them to avoid destruction. Those who went to Durango emerged from the Punitive Expedition relatively unscathed, but the ones who remained in Chihuahua were decimated by American forces. Two of Villa’s most trusted commanders, Candelario Cervantes and Julio Cardenas, were killed during the campaign. The latter’s demise was part of a hair-raising adventure that George Patton would recall—and lengthily recount—for the rest of his life (see the following article).

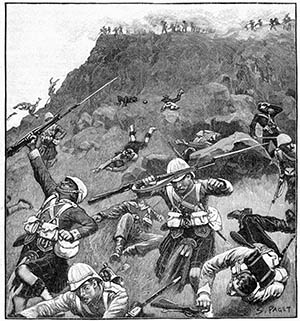

Although the soldiers weren’t aware of it at the time, the Punitive Expedition’s high-water mark came about a month before Patton’s adventure. On the morning of April 12, Major Frank Tompkins and K and M Troops of the 13th Cavalry entered Parral, 516 miles from the border. It would be the deepest any American soldier ever got into the Mexican heartland. A local Carranista general told Tompkins to leave, which he did without incident, but just outside town the government forces began firing on the American column. It ignited a running firefight in which the Americans, although outnumbered, managed to inflict heavy casualties on their attackers. Eventually, Tompkins and his men made a stand at Santa Cruz de Velegas, eight miles from Parral, before being rescued by elements of the 10th Cavalry under Major Charles Young, one of the few African American officers in the service.

When Pershing heard of the incident he was outraged, but the Mexican authorities refused to apologize. For safety’s sake, the general decided to consolidate his forces. His advance headquarters would be in Namiquipa, about 180 miles north of Parral and 90 miles south of his main base at Colonia Dublan.

The Last Glory of the Punitive Expedition

The Punitive Expedition had one final moment of glory, this time at a place called Ojos Azules. Major Robert L. Howze of the 11th Cavalry received a message from the townspeople that they were being threatened by Villistas. Howze responded with alacrity, pressing forward with 370 troopers. Howze found Villa’s men at Ojos Azules and launched an attack at dawn on May 5. Thirty Apache scouts led the way, dismounting and blazing away at the surprised bandits, many of whom had just been rudely awakened. Lieutenant A.M. Graham of Troop A, 11th Cavalry, gave the order, “Draw pistols,” and each trooper took his Colt Browning from his holster. The bugler sounded “Charge” and the 11th went forward at the gallop.

Panicky Villistas swarmed out of a cluster of buildings, trying to get to their horses. Another 30 or 40 climbed onto roofs to pour a hail of lead down on the horsemen. Graham took his horse over a fence and shot one bandit out of the saddle at point-blank range. Some Villistas tried to make a stand near some pine trees, but the troopers dismounted and returned fire. The battle was over in 20 minutes, with Villa’s men either dead or in full flight. Some 60 bandits were killed at Ojos Azules. Amazingly, there were no American casualties, even though the firing had been heavy. The last cavalry charge on the North American continent was an undeniable U.S. triumph.

Boyd’s Fatal Mistake

In hindsight, the Punitive Expedition should have withdrawn after Ojos Azules. Tensions were rising, and the longer the Americans stayed on Mexican soil, the greater was the possibility that an incident would trigger a full-scale war between the two angry countries. In June, just such an incident pushed the two countries to the very brink of war. Pershing found himself vastly outnumbered by gathering Carrancista forces, his 100-mile-long line of communication in danger of being cut. He dispatched Captain Charles C. Boyd and C Troop of the 10th Cavalry to reconnoiter.

Boyd wanted to ride through Carrizal, but Mexican General Felix Gomez told the American soldiers to fall back. “Tell the son of a bitch,” Boyd declared, “that we are going through.” It was a fatal error of judgment. Fighting soon broke out, and this time the Americans were defeated. The Buffalo Soldiers lost cohesion when most of their officers were killed or wounded. The action at Carrizal was a Mexican victory, although something of a Pyrrhic one, since 74 Mexican soldiers lay dead, including General Gomez. American losses were also heavy—12 troopers dead on the field, including Boyd, 10 wounded, and 24 captured. A neutral fact-finding commission later blamed the incident solely on Boyd.

From Mexico to Europe: The Punitive Expedition Withdraws

Huge anti-American demonstrations erupted in Mexican cities, and American newspapers joined a swelling chorus for war. Wilson and Carranza kept their heads. Carranza knew that Villa’s original plan was to get him in a war with the United States, and the white-bearded old politician was too canny for that. Wilson, increasingly concerned with German successes in the ongoing world war in Europe, had no wish to become bogged down in Mexico. Both sides pulled back, tensions cooled, and war was averted.

Pershing pulled back to Colonia Dublan, where he remained in camp for six months while the two governments worked out a mutually face-saving solution. To counteract boredom and a concomitant lack of discipline, Pershing ordered intensive training for the men, but the ceaseless Mexican windstorms took their toll on the soldiers’ morale. “We are all rapidly going crazy from lack of occupation and there is no help in sight,” Patton wrote his father in July. American public opinion reversed itself. “Through no fault of his own the ‘Pershing punitive expedition’ has become as much a farce from the American standpoint as it is an eyesore to the Mexican people,” declared the New York Herald. “Each day adds to the burden of its cost to the American people and to the ignominy of its position. General Pershing and his command should be recalled without further delay.”

The Punitive Expedition finally withdrew in February 1917. The soldiers may not have captured Pancho Villa, but they decimated his forces and gained combat experience under grueling conditions. A few months later, Pershing went on to become commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, leaving the dishonor of the Mexican campaign far behind.

The Columbus raid was the beginning of the end for Pancho Villa. He enjoyed a brief resurgence of popularity after the Americans went home, but the comeback was short-lived—as was Villa himself. Bought off by the Carranza government with land and a large hacienda so that he could retire in style, the wily old bandit could not escape his political enemies. On July 20, 1923, seven gunmen pumped 150 shots into Villa’s car as he drove through Parral. Sixteen bullets struck Villa’s body and another four hit him in the head, leaving Villa as dead as any of his long-ago victims in Columbus. It was a fitting end to an inglorious career.

I first read about Patton’s escapades in the Pershing expedition in the book, “Patton, a Study in Command”, by H. Essame. Along with this article, it demonstrated George Patton’s thirst for combat, whether to gain the glory that he read of about numerous warriors before him, or just to experience the high emotions and be a leader during the fighting. He read about and trained for combat from an early age, and, as he told Gen. Pershing, he wanted to be in the expedition “more than anyone else.” I believe that to be exactly the case with him. He was a true soldier. Thanks for making these articles available.