By Kevin M. Hymel

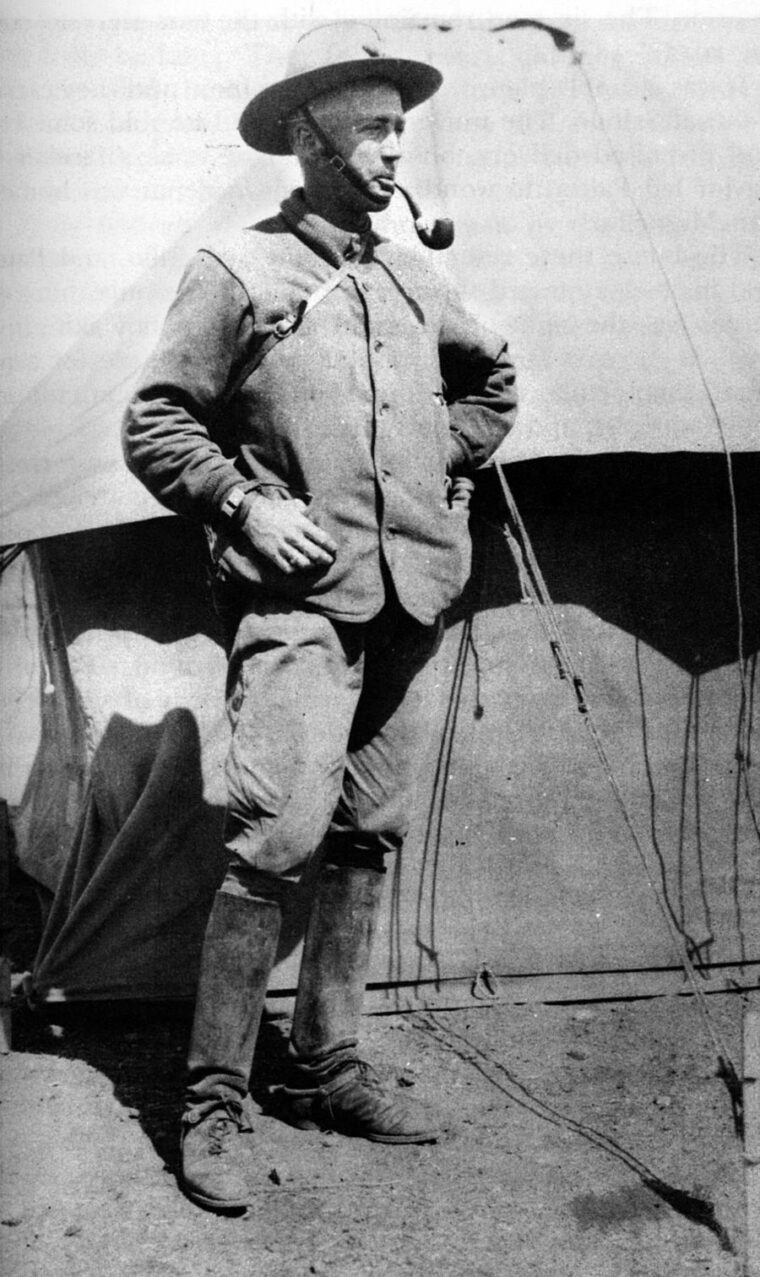

When Brig. Gen. John S. Pershing began assembling a force of 10,000 infantry and cavalry for a punitive incursion into Mexico in the spring of 1916, almost every soldier in the U.S. Army was eager to take part in the nation’s first major military campaign since the Philippine-American War. One of the most eager was Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr., a 31-year-old graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Patton, a career cavalryman, expert swordsman, and Olympic athlete, viewed the expedition as a golden chance to see his first hostile action.

Since his unit was not slated to join the expeditionary force, Patton applied for a personal position on Pershing’s staff, even though there were no vacancies. Pershing heard about Patton’s application and called him, promising to see what he could do. Unsatisfied, Patton visited the general’s quarters one night, offering to do any task, no matter how menial, just to be included in the campaign. Said Pershing: “Everyone wants to go. Why should I favor you?” Patton immediately replied, “Because I want to go more than anyone else.” Impressed by the young officer’s frankness, if nothing else, Pershing made Patton one of his aides.

The Punitive Expedition to capture and punish Mexican rebel Pancho Villa and his men met with little initial success. The forbidding terrain was unfamiliar, and the rugged mountains of northwest Mexico provided ample hiding spots for Villa and his bandits. At the beginning of April, however, Pershing received reports that one of Villa’s most trusted commanders was in the area. General Julio Cardenas, head of Villa’s personal bodyguard—the Dorados, or “Golden Ones”—was considered a prime catch. Patton was privy to the same field reports as Pershing, and he pestered the general with request after request to join the hunt for Cardenas. Pershing relented and temporarily assigned Patton to Troop C of the 13th Cavalry.

The search for Cardenas already had produced some results before Patton joined the hunt. In early April, troopers from the 16th Cavalry discovered Cadenas’s wife and baby at a San Miguelito ranch. A follow-up search by Patton and his troopers revealed Cardenas’s uncle. The Americans hammered him for information. “The uncle was a very brave man,” Patton reported, “and nearly died before he could tell me anything.” On May 10, Patton searched another location, Rubio Ranch, but came up empty.

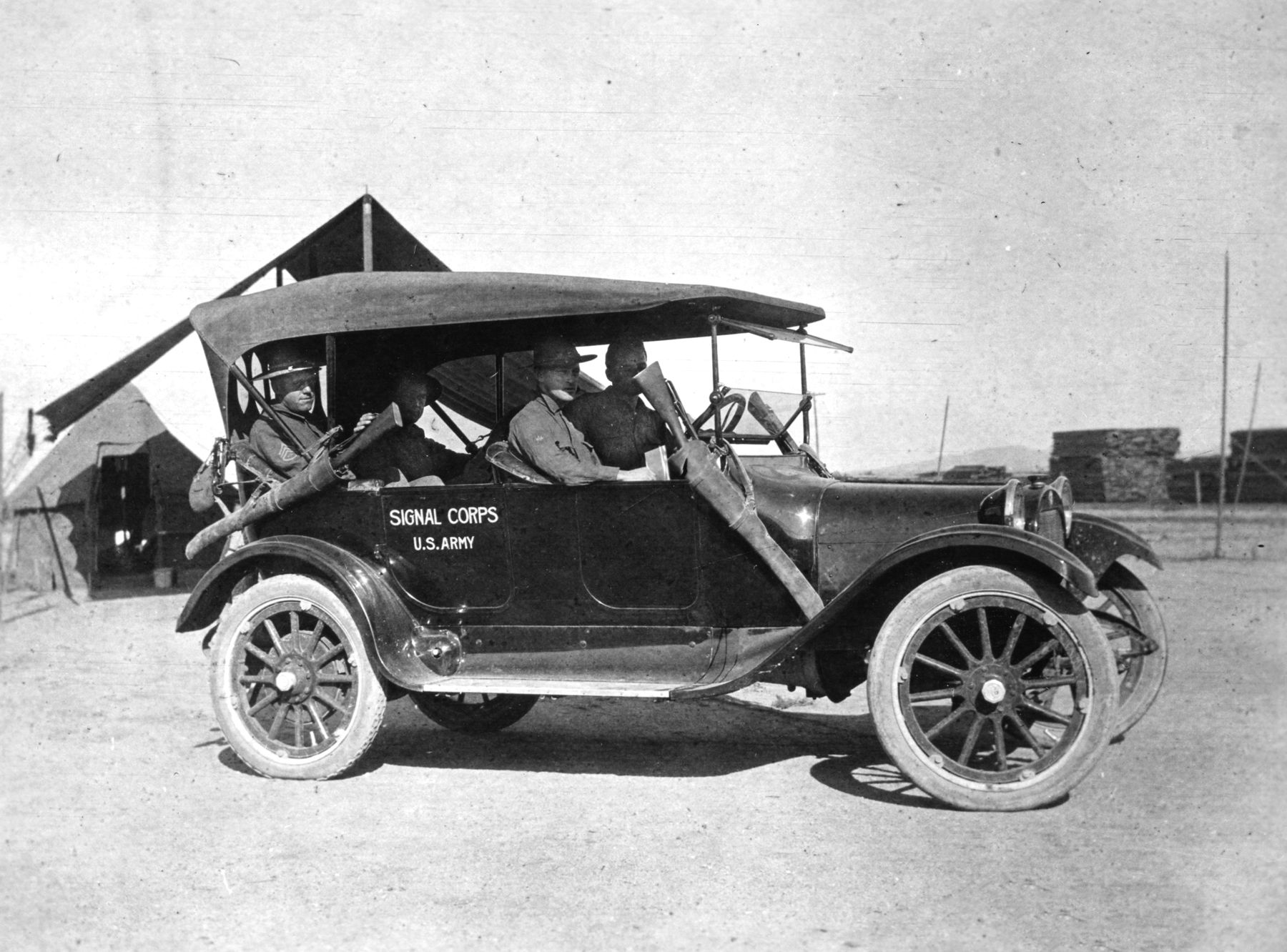

Patton’s next opportunity came four days later when Pershing sent him on an errand to obtain corn. Patton saw this as a chance to search the area again for Cardenas. His assets on the small trek were three automobiles and 10 infantrymen, including two civilian scouts and two civilian drivers. They drove five to a car. The soldiers were armed with bolt-action Springfield rifles, while Patton carried an ivory-handled Colt 1873 Peacemaker, a single-action .45-caliber revolver. He kept only five shells in the six-chambered barrel to prevent an accidental discharge.

After purchasing corn at the Coyote and Rubio Ranches, Patton spied 50 or 60 men who, although unarmed, seemed to him to be “a bad lot.” Some of the men were recognized by one of his guides who had previously been a rebel soldier. Patton suspected that Cardenas was in the area and decided to search Rubio again, but he knew he would have to do it quickly if he wanted to surprise the cagey Villista.

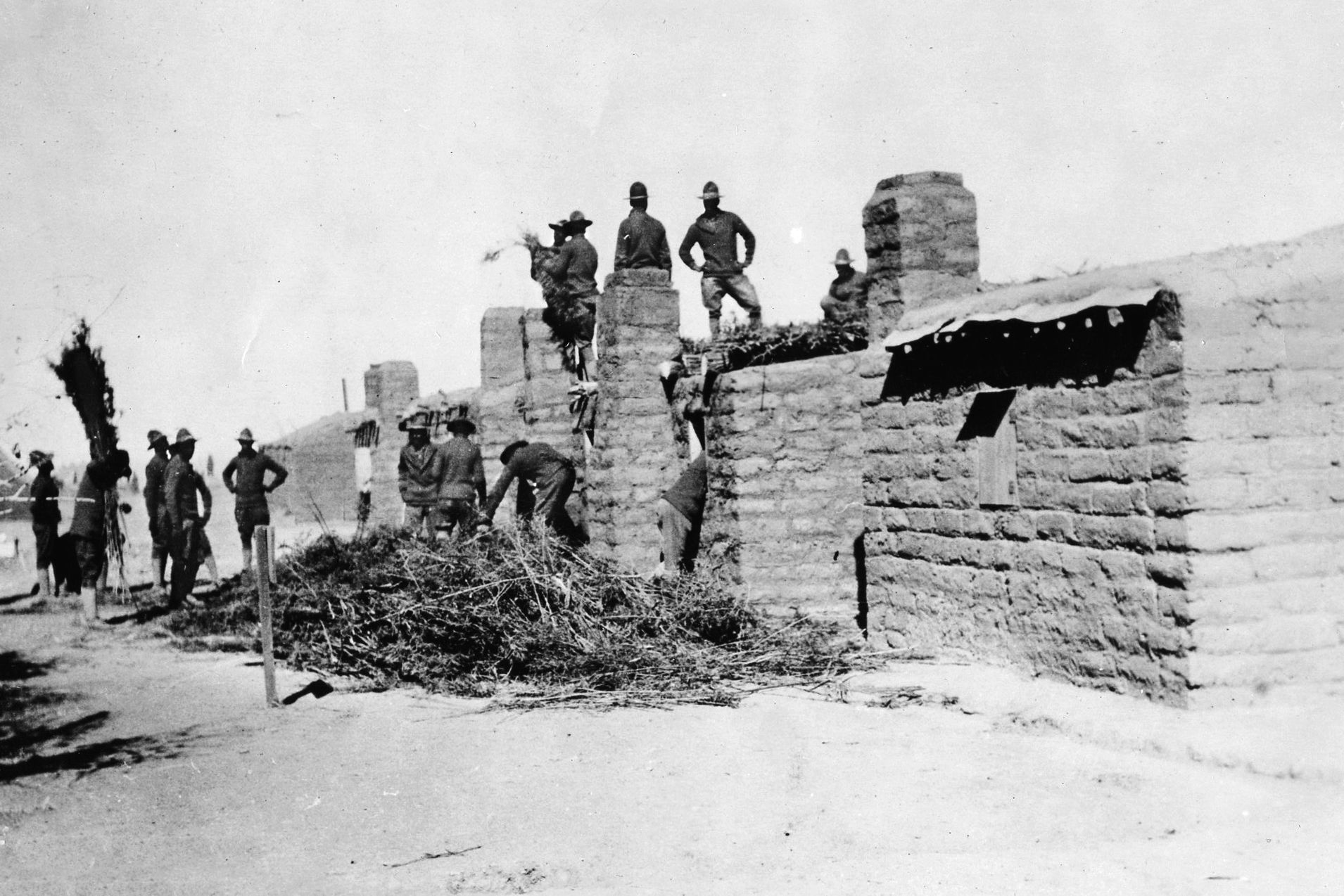

Patton was familiar with the layout of the ranch from his previous inspections. It was a simple design of two buildings. The thatched-roof main house surrounded a large courtyard; an arched gate on the east side served as an entrance. A few yards to the northwest stood a horse corral. The ranch was bordered on the east by two lakes and a stream and to the south by a wooden fence that ran parallel to the house and intersected a stone wall that ran along the river. The only way out for horsemen was through the arched gate.

After leaving the ranch, Patton gathered his men and explained his plan. They would drive up to the ranch from the south. Patton’s car would stop just past the corral, and Patton and three other soldiers would run east to cut off any escape route. The other two cars would stop short of the wooden fence, and three men from each car would charge out, link up with Patton, and begin searching the buildings. Those left at the cars would block anyone escaping west.

The three cars raced for the ranch over undulating ground that prevented them from being spotted until they were right on top of their target. As Patton’s car sped past the ranch, he noticed a group of men skinning a cow near the lakes. One of the men ran to the house before returning to his work. Patton’s car screeched to a halt as he and his fellows jumped out and ran across the northern yard. Patton, clutching a rifle, led the way, closely followed by his unarmed scout, Healon Lunt. They reached the court and circled back to the arched entrance. The other two cars then arrived at their destinations, unloading more men to link up with Patton. Because they were unfamiliar with the ranch layout, they took longer to reach the eastern side.

Suddenly, three Mexicans on horseback, wielding rifles and pistols, charged through the arched gate. They spotted Patton and wheeled around to the right to escape. Patton drew his pistol but held his fire, waiting to see what the riders would do and trying to pick out Cardenas. Pershing’s rules of engagement prevented American soldiers from firing on anyone until hostile intent was verified. “Halt!” Patton shouted, but the men galloped on. When they saw Patton’s reinforcements charging toward them, they reined in their horses, turned around, and charged east, leveling their weapons at Patton and Lunt and opening fire.

Patton stood his ground, his .45-caliber revolver cocked, as the three armed Mexican rebels charged him and his scout. “The guns seemed pointed right at me,” Patton recalled. The riders opened fire at a distance of 15 yards. Patton did not hear the passing bullets, but he returned fire, snapping off a shot.

Bullets kicked up the gravel at Patton’s feet. He responded by emptying his revolver—all five shots—at the riders. Two bullets hit home, breaking the arm of one man and wounding his horse. Just then, the Americans arriving from the west caught up with Patton and Lunt and opened fire as well. Patton ducked and ran over to the house to get out of their line of fire, calling for Lunt to follow. The Mexicans, now clearly identified as Villistas, swiveled around in their saddles and returned fire. Several bullets struck the wall above Patton’s head as he reloaded, showering him with adobe dust. Momentarily blinded, he could not see the first horseman, who peeled away from the other riders and charged back toward the house beneath the archway.

Patton looked up from reloading and saw a Villista charging. Knowing that he had a better chance of wounding the horse than the rider, Patton aimed low and fired a shot into the animal’s hip, breaking it. The horse rode a few yards and went down. When the dust cleared, the horse lay on the ground, the rider pinned beneath. Patton held his fire as the man extricated himself from the horse and struggled to rise, gun in hand. He was immediately riddled by gunfire from Patton, two soldiers, and one of the guides. The man crumpled over and died.

With one bandit down, the Americans shifted their attention to the other two. One of the escaping men had gotten almost 100 yards away before Patton pulled his rifle to his shoulder and fired three times. The troopers around him joined in the deadly chorus, and the man went down. Two of Patton’s men went to check on him and shouted back that the third man was escaping south, running alongside the stone wall 300 yards away. They raised their rifles again and fired.

The man went down, and one of the scouts, E.L. Holmdahl, ran over to him. The wounded man raised his left hand to surrender—his right arm had been broken by Patton’s original fusillade. Holmdahl thought he was accepting the man’s surrender, but as Holmdahl got within 20 feet, the man raised his pistol and fired. The shot missed and Holmdahl quickly fired a round into the man’s head. Now, three Villistas were dead.

Patton knew that Cardenas commanded approximately 35 men, and he was concerned about their immediate retribution. To ensure no surprises, he had his men lean a dead tree against the side of the house and climbed to the thatched roof. Almost comically, he immediately fell through to his armpits. If anyone had been in the house, they could have easily shot Patton while his feet dangled helplessly in the air. Patton extricated himself and made a quick scan of the area. He saw nothing except the men skinning the cow. “They never looked at us at all,” he reported.

With the exterior secure, it was time to check out the house. Patton summoned the cow skinners. “We each got behind a Mex and went in.” Patton did not mention if his “volunteers” walked into the house at gunpoint, but they definitely led the way. Inside, Patton found a blood trail and followed it to a riderless horse with a silver saddle and saber. The Mexican with the broken arm had ridden back into the house, dismounted, and jumped out a window to reach the stone wall.

Upon inspecting the rest of the house, the men found mostly women and old men, including Cardenas’s wife, mother, and baby. Everyone remained silent as the Americans poked around. They may have kept silent to protect a hiding Villista. In 1963, an old, gray-haired general from the Mexican general staff told one of Patton’s daughters that he knew her father well. When she asked how, he told her “I shoot at him many times—from behind walls, from behind haystacks, from behind houses—I was with Pancho Villa!”

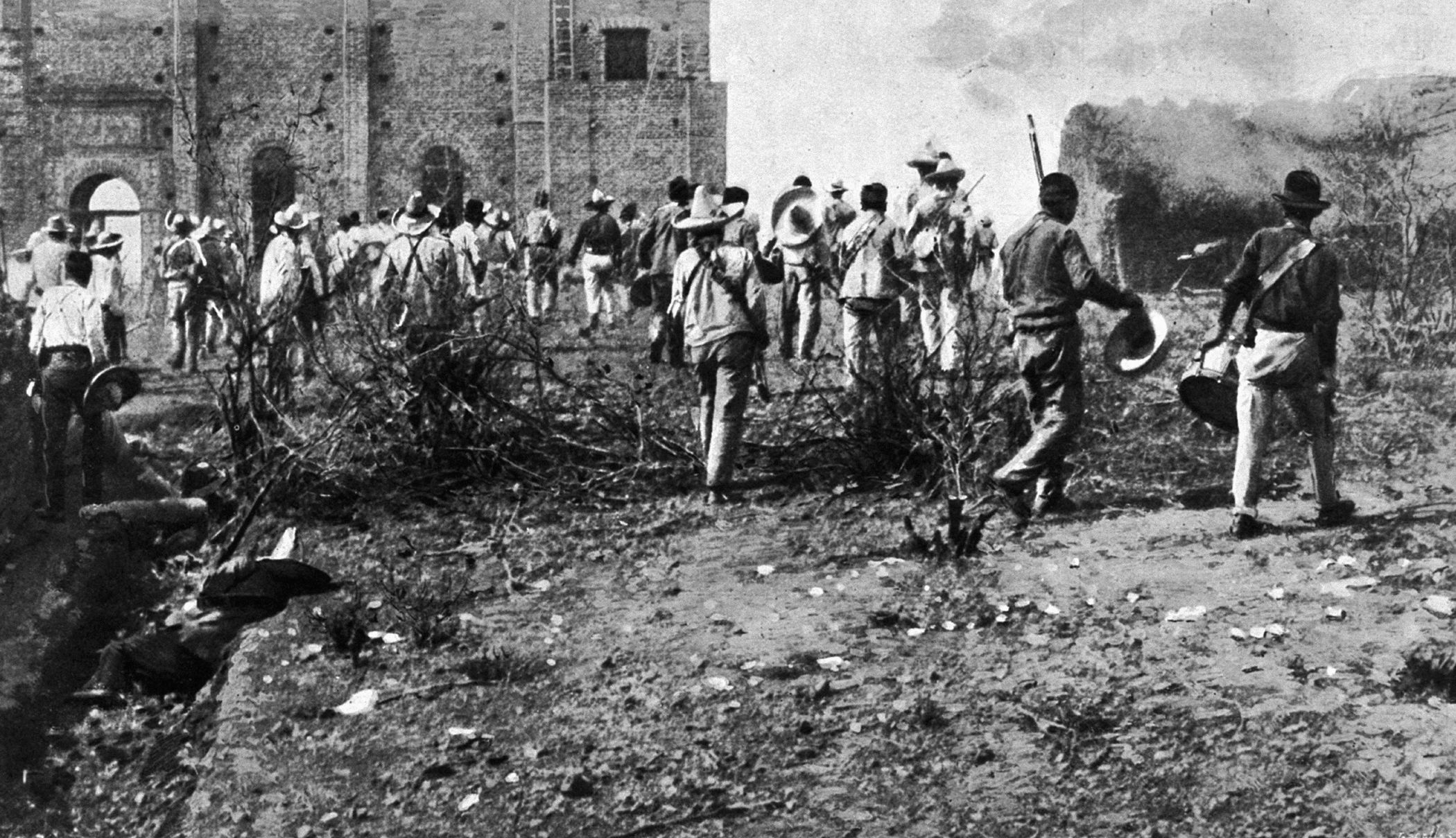

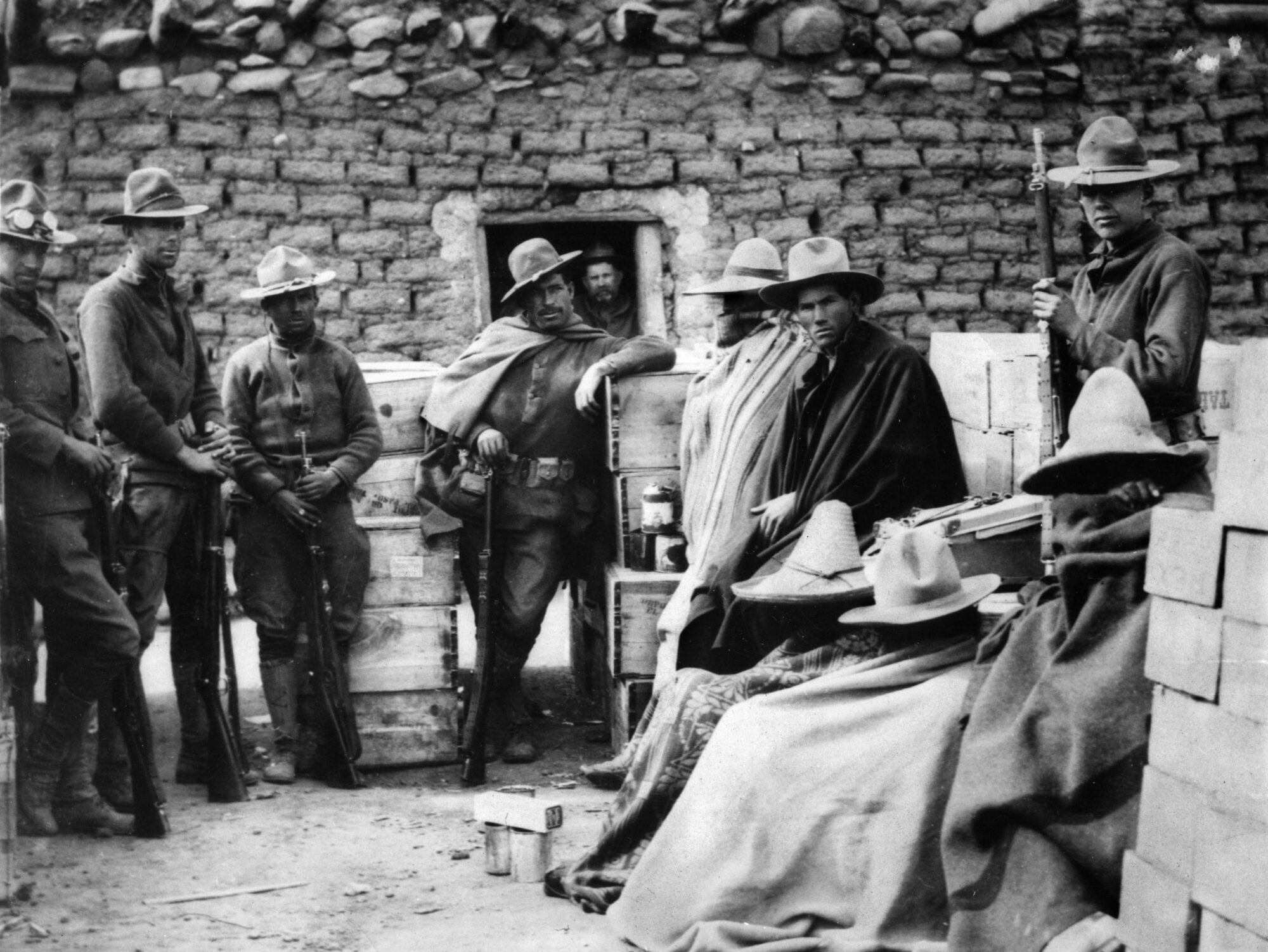

Back outside, the Americans questioned the cow skinners and discovered that the last man killed, and the first one Patton shot, was Julio Cardenas. Patton had nailed his target. The men gathered up the all the weapons while Patton snagged Cardenas’s silver-tipped saddle and saber for himself. All three dead men wore U.S. Army trousers and possessed Army blankets stenciled “Thirteenth Cavalry.” They had obviously been part of the Columbus raid. Two of the dead men were unceremoniously strapped to the hoods of the cars, but before Cardenas could be brought over to the vehicles, a group of 40 Mexicans rode up on the area, firing rifles.

Patton’s men were nervous, outnumbered almost 3-to-1, but they stood their ground while Cardenas’s corpse was strapped to the hood of the last car. Patton was hesitant to start another fight. No one knew where he was, and no help could be expected. He also worried that “a shot to the gas tanks to the rear of the cars would put them out of action. It was better not to wait.” They jumped into the cars and took off in haste. Patton reported officially: “We withdrew gracefully.”

Patton made one last tactical decision as they headed back to headquarters. Passing the town of Saltillo, he ordered one of his men to climb a telephone pole and cut down the wires. He did not want anyone warned about what had happened at Rubio. When the locals saw the dead bodies on the cars they began to shout and taunt the Americans, but no one tried to stop the vehicles as they rode by.

The cars rolled into camp to the amazement of the soldiers and reporters, who gathered around to see the bodies strapped over the hoods like hunting trophies. The soldiers teased Patton about not using his saber on his quarry. Pershing ordered a troop of cavalry to ride back to Rubio to see if any more Villistas were in the area. He complimented Patton, saying that he had done more in a day than the entire 13th Cavalry Regiment had done in a week. He allowed Patton to keep Cardenas’s saddle and saber. The soldiers buried the bodies as the sun went down, with one old sergeant offering a droll eulogy: “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. If Villa won’t bury you, Uncle Sam must.”

It had been a long day. Patton’s party had taken off for the corn at noon and returned to camp around four. In that time, he had proved his military prowess. He staked out his target, made a quick plan to seal off the area, and brought firepower to bear. He stood his ground and scored hits in the opening round of the firefight that helped kill the bandits. He then conducted an aerial recon, despite falling partially through the roof. Finally, he surmised the larger strategic implications of his actions and had the telephone lines cut to prevent word of his actions from spreading and to prevent anyone from coordinating an ambush along the return journey.

Rubio Ranch was significant for another reason. It was the first time the U.S. Army had used the combustion engine in combat, with automobiles replacing horses in the cavalry-style raid. Within 25 years, horses no longer would play an active role in American war making.

The Punitive Expedition ended in February 1917. It had lasted 10 months and failed in its main objective of capturing Villa. The expedition’s greatest success was the wartime experience it gave to a new generation of leaders. Many of the officers would play prominent roles during World War I. Pershing would be promoted to full general and lead an army of four million into the bloody trenches of Europe. Patton would apply his knowledge of motorized vehicles to a new weapon making its debut in France—the tank.

Patton had survived his own version of the gunfight at the O.K. corral, but he did not escape Mexico unscathed. Five months after the Rubio Ranch affair, he was in his tent, pumping kerosene into a lamp, when the lamp exploded. His face and hand caught fire and he ran outside and put out the flames. The burns would eventually heal, but for days Patton was forced to ingest his food through a straw.

The Rubio Ranch incident cemented the image of Patton the fighter. The battle caused a short-lived sensation back in the United States, where people hungered for good news from Mexico. The Army had not had much luck finding bandits before Patton’s cars raced to the ranch. Patton completed his new image by cutting two notches into the ivory handle of his Colt .45—even though he could not be sure if he had actually killed anyone.

Throughout the Rubio Ranch gunfight, Patton had remained cool and calculating. In his tent the night after the shootout, Patton wrote to his wife, “I have always expected to be scared [in a fight], but I was not, nor was I excited.” He had only one thought in mind the whole time: “I was afraid they would get away.” They didn’t.

They had rules of engagement back then? Who would have thunk?