By Mike Phifer

Maharaja Ranjit Singh, ruler of the Sikh empire in northern India, was dead. Under his intrepid leadership, starting in 1799, Afghan control over Punjab, or Five Rivers Land, was thrown off and the Sikh empire flourished over the next 40 years. Having seen the might of Great Britain and the British East India Company, Ranjit signed a nonaggression treaty with the British in 1809 establishing the River Sutlej as the southeastern border of Punjab. He then expanded Sikh territory through warfare and annexation. By 1839, his kingdom reached from Tibet to Sind and from the Himalayas to the Khyber Pass.

With Ranjit’s death in 1839, leadership of the Sikh empire passed to Karak Singh, his oldest son. Karak did not remain in power long. Karak’s son, Nau Nihal Singh, took over leadership briefly but died mysteriously on the very day his father was being cremated. Next came another of Ranjit’s sons, Sher Singh, who managed to rule for two years before he too was killed. It was becoming clear that the real power lay with the Sikh army.

Under Ranjit’s rule, the Sikh army, called the Khalsa (meaning “pure”) had been modernized. Realizing that he needed a strong army to maintain his hold on the empire, Ranjit had dramatically overhauled his armed forces. No longer would cavalry be the core of the army. Instead, that role was taken over by the infantry, trained and drilled in European tactics. Napoleonic veterans and experienced officers from Europe and America were recruited to train the Sikhs. Artillery also played a big role in Ranjit’s reorganization. The army’s gunners were well trained and equipped with guns ranging from 3- to 48-pounders. The cavalry increasingly found itself in an auxiliary role. By 1845, six years after Ranjit’s death, the Khalsa boasted almost 54,000 regular infantry, 6,235 regular cavalry, 16,000 irregular cavalry, and 10,968 artillerymen. There were also thousands of irregular infantry and levies if needed.

The soldiers of the Sikh army were republican in sentiment and elected military committees called Punchayats that allowed them to flex their power over Punjab’s rulers, who tried to buy their support with healthy bribes. Not surprisingly, the rulers at Lahore feared the army. Vizier Jowahir Singh, brother to Queen Regent Maharani Jindan Kaur, was brutally murdered by army leaders while desperately trying to bribe them.

After the murder of her brother, Maharani Jindan managed to obtain the support of the military and acted as regent for the young and only surviving son of Ranjit Singh, Maharaja Dalip Singh. In November 1845, Jindan gave the position of vizier to Lal Singh, who among other things had been the raja of Rhotas and Domelia. Command of the Sikh army went to General Tej Singh. These two men, along with Jindan and Raja Gulab Singh, ruler of the annexed provinces of Jammu and Kashmir, would be leading figures in the coming war with the British.

The Seeds of War in India

Across the Sutlej, the British watched with concern the intrigue taking place at Lahore. The new governor-general of India, Sir Henry Hardinge, consulted with his commander in chief, Sir Hugh Gough, in August 1844 on military preparations in the north. A year earlier, Gough had cautioned the former governor-general that 40,000 troops would be needed for offensive operations against the Sikhs. Now he suggested a much smaller force for defensive measures, telling Hardinge that he was “particularly anxious to avoid any military preparations that might excite remark.” Hardinge reinforced the border garrisons with almost 23,000 more men. Despite the troop increase, Hardinge didn’t think war was imminent. He was wrong.

Sikh soldiers were angry over the British increasing their troops along the border, believing, not without justification, that the British had their eyes on the Punjab. Major George Broadfoot, Hardinge’s agent in Lahore, did not help the situation when he ordered a Sikh magistrate and his party fired upon for moving into the Sutlej region without his permission. The Sikh army wanted more than just to defend its empire, however. Its leaders believed the British were vulnerable after the Redcoats’ Afghan disaster in 1842, which saw an entire army wiped out. Confident of their strength and fighting prowess, the Sikhs believed they could drive the British out of India as well.

The Sikh soldiers were not the only ones who wanted war. By late 1845, the treasury was running out of rupees to bribe the army. To end the power of the Khalsa and regain control, Maharani Jindan, Tej Singh, Lal Singh, and Gulab Singh hoped to see the British defeat the Sikh army. With the Khalsa out of the way, the leaders hoped they would receive recognition and assistance from the British.

First Clash Between the Sikh and British Empires

On December 11, a Sikh army of roughly 40,000 men commanded by Lal Singh and Tej Singh crossed the Sutlej River in two different spots. Punjab was now at war with the British. The Sikh force under Tej Singh moved on Ferozepore, where a British garrison of roughly 7,000 men, mostly Sepoys, or native Indian troops, were stationed under the command of Maj. Gen. Sir John Littler. Meanwhile, the main Sikh force under Lal Singh marched toward Ferozeshah, east of Ferozepore, where they set up camp and awaited the main British force.

News of the Sikh army crossing the Sutlej reached the strong British garrison at Ambala on December 12. Gough wasted no time in marching his army of about 10,000 troops over the sandy roads north toward Ferozepore. After receiving word of Gough’s advance on the evening of December 17, Lal Singh ordered a force of around 3,500 infantry, and possibly as many as 10,000 cavalry and 22 guns to march for Mudki the next day to face the British advance.

Gough’s worn-out and dust-covered soldiers arrived at Mudki around 1 pm. The troops who marched out of Ambala with him had come a staggering 150 miles in six days. The British and Indian battalions advanced forward in echelon formation with the right wing leading the frontal assault. Sikh musket fire greeted the red-coated troops as they pushed forward into the jungle. The Sikh fire was deadly as their muskets flashed and crashed in the darkness. For six hours the battle raged with the Sikh infantry finally being driven back and forced to retreat. By midnight the battle was over and the British were in possession of the battlefield.

“Another Such Victory and We Are Lost”

The British and Indian forces had suffered 215 killed including a number of senior officers. Among them was Maj. Gen. Sir John McCaskill, who commanded the 3rd Division. Gough’s army also suffered 657 wounded in the engagement. Sikh’s forces lost about 300 killed and a similar number of wounded to the British. Seventeen of their guns were captured.

For the next two days the British licked their wounds. Hardinge, who as governor-general was Gough’s superior, offered to serve under the 66-year-old commander in chief. Both men were veteran officers, with Gough having joined the army in 1794 and fought the Crown’s enemies in South Africa, the Caribbean, Spain, and Portugal and in the First Opium War and Gwalior Campaign. The 60-year-old Hardinge was no stranger to the smell of gunsmoke himself, having serving in Canada, Portugal, and Spain. At Ligny in 1815 he lost his left hand. Later, he entered politics and rose through the Wellington government to his current position.

Gough ordered his newly reinforced army to move out on December 21. Around the village of Ferozeshah, the Sikh army was entrenched in a quadrangular position that stretched for 1,800 yards in length and more than that length in breadth. After reconnoitering the Sikh entrenchment, Gough opted to attack from the south, even though the northern part of the camp had been left undefended by Lal Singh. The ensuing Battle of Ferozeshah was a bloody one, with the British and Indians suffering 694 men killed, of whom 54 were officers, including Brig. Gen. William Wallace and Major George Broadfoot. Gough’s force also had 1,721 men wounded. The Sikhs suffered 2,000 to 3,000 causalities. After the battle, Gough had no intention of renewing the advance until his army had rested, received reinforcements, and been resupplied. The stench of the battlefield caused Gough to move his army seven miles west of Ferozeshah.

In London, the costly battle at Ferozeshah brought on torrents of criticism in Parliament. One member described it, all too accurately, as “a high cost for a victory that was not very far removed from failure.” Hardinge himself shuddered, “Another such victory and we are lost.” At the front, much needed help was already on the way. A large siege train with 4,000 wagons and carts full of supplies was coming from Delhi and expected to reach the army sometime in early February. On January 6, almost 10,000 troops under the command of Sir John Grey reinforced Gough.

Sikh Supply Troubles

The next day Gough moved his army north to Arufkee, with an advance guard being posted at Malowal. On the 12th, he set up headquarters at Bootewalla, only five miles from the Sikh army. Both sides were now in view of each other. The combined Sikh army camped near the Harik Ford on the north bank of Sutlej was also badly in need of supplies and reinforcements, neither of which were coming in any great numbers from Lahore. In an attempt to alleviate the supply problem, the Sikhs sent a delegation of 500 men into the capital to ask for help. Maharani Jindan agreed to see them from behind a screen with the young Dalip present. The delegation told her of their desperate need for assistance. She told them that Gulab Singh had sent them vast supplies. “No he has not,” they roared back, adding, “We know the old fox; he has not sent breakfast for a bird.” They were right. Gulab Singh had provided very little to help, holding back much needed troops for his own use.

Tempers began to flare as the parley went on. Watching the meeting was American mercenary Alexander Gardner, who described what happened next: “I could detect that the Rani was shifting her petticoats; I could see that she stepped out of it; and then rolling it up rapidly in a ball, flung it over the screens at the heads of the angry envoys, crying out, ‘Wear that, you cowards! I’ll go in trousers and fight myself!’ The effect was electric.” The delegates were stunned by her actions. Then according to Gardner they shouted, “Dalip Singh Maharaja, we will go and die for his kingdom and the Khalsaji!” They returned to the army empty handed.

A Crucial Victory For the British

While the main Sikh army struggled to get supplies, another force consisting of 12,000 men under the command of Ranjur Singh crossed the Sutlej 44 miles to the east to threaten the small British garrison at Ludhiana. More than Ludhiana was at stake for the British. Ranjur Singh’s army could also march on the key supply base at Bassian, which was vital to Gough’s supply line from Delhi. This Sikh force could also pose a serious threat to the slow-moving siege train heading north to join Gough.

After capturing the town of Dharamkot on January 18, Maj. Gen. Sir Harry Smith received orders to deal with Ranjur Singh. Gaining reinforcements along the way, Smith attempted to skirt Ranjur Singh’s force at Budowal. The two sides exchanged fire as Smith’s force marched by the village, screened by his cavalry. Unfortunately for Smith, he lost much of his baggage train to Sikh cavalry. Smith’s reduced force then made its way to Ludhiana.

Ranjur Singh moved his army near the village of Aliwal, where he entrenched himself along the Sutlej to cover the ford. After receiving more reinforcements, Smith, with a force of 10,000 troops, successfully attacked Ranjur Singh’s 18,000-man army on January 28. The Sikhs suffered roughly 3,000 casualties in the battle, many while attempting to escape across the Sutlej. Smith suffered 598 casualties. The victory had important ramifications for the British. If things had gone badly, said Smith, especially after the blood lettings at Mudki and Ferozeshah, India “would have been one blaze of revolt.”

Preparing For a Decisive Battle

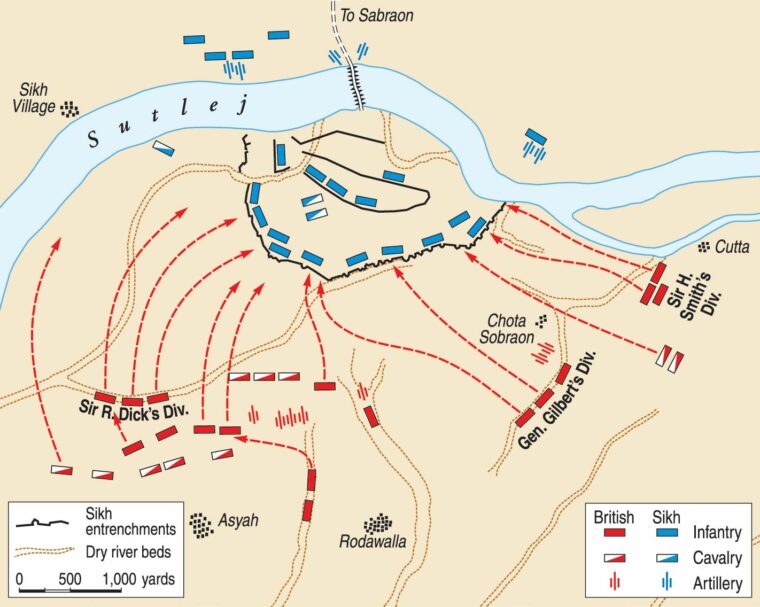

Having lost 67 cannons, 40 swivel guns, and its baggage, Ranjur Singh’s army retreated to Phillour, 12 miles east of Aliwal. Leaving a small force at Ludhiana to watch Ranjur Singh, Smith set out on February 3 to return to the main British force. The main Sikh army, meanwhile, had been busy. Once it had constructed a bridge built on boats across the Sutlej, it then built a strong entrenchment in the bend of the river on the south side. The entrenchment’s southern side stretched for a mile and three quarters with a dry riverbed in front of it. The left or east side of the entrenchment, which also partly skirted a dry river bed, ran for about half a mile back to the river. On the right or west side, the entrenchment was weaker and did not reach back all the way to Sutlej. Inside the entrenchment were three more lines made up of mostly trenches and pits that faced south. The line closest to the river helped protect the bridgehead.

Smith’s force marched into the British camp on February 8. That same day the rest of the long awaited siege train arrived. While this was going on, Hardinge and Gough were discussing their options for attacking the Sikhs. In the end Gough’s plan won out. On the afternoon of February 9, Gough called a meeting with his division and brigade commanders to discuss his plan of attack. From intelligence reports, Gough knew that the Sikh right was vulnerable. This is where the main attack would be made, early the next morning. At 2 am on February 10, Gough’s British and Indian troops were quietly awakened, making sure no bugles were blown or drums beaten. The soldiers formed up and marched out in the darkness to take up positions for the coming climactic battle of the short, bloody war.

The Sikh and British Orders of Battle

Forming on the right of the British line was Smith’s 1st Division, which consisted of the 1st and 2nd Infantry Brigades under the command of Brig. Gens. George Hicks and Nicholas Penny, respectively. They were supported by two troops of horse artillery and a cavalry brigade. Positioned in the center near the small village of Sobraon was Maj. Gen. Sir Walter Gilbert’s 2nd Division made up of Brig. Gen. Charles Taylor’s 3rd Brigade and Brig. Gen. James MacLaren’s 4th Brigade. The 19th Field Battery was also with Gilbert. On Gilbert’s right, between his division and Smith’s division, was a battery of heavy guns. Another battery of heavy guns was on Gilbert’s left. Maj. Gen. Sir Robert Dick, now in command of the 3rd Division, was placed on the British left flank. He had three brigades, with Brig. Gen. Lewis Stacey’s 7th Brigade being in the first line. Some 200 yards behind him was Brig. Gen. Christopher Wilkinson’s 6th Brigade in the second line, while Brig. Gen. Thomas Ashburnham’s 5th Brigade was in reserve.

Behind the reserve was Brig. Gen. John Scott’s cavalry brigade; three Sepoy infantry regiments were nearby. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Charles Cureton’s cavalry brigade of Maj. Gen. Sir Joseph Thackwell’s cavalry division was ordered to make a feint against a ford to the right in hopes of drawing off Sikh forces. Gough had positioned 19 of his 24 heavy artillery pieces facing the southwest angle of the Sikh entrenchment. This was the angle Dick’s division was to attack head-on.

In all, Gough’s army numbered around 20,000 men and 65 guns of various caliber. Shrouded behind the heavy fog that delayed Gough from attacking at daylight as planned were roughly 20,000 Sikh soldiers behind their entrenchment with their backs to the Sutlej. In all, the Sikh forces numbered 42, 626 men, but more than half of them were on the north side of the river with Lal Singh. Tej Singh commanded the troops on the south side of the river.

Commanding the left side of the entrenchment was the veteran general Sham Singh. He had served with Ranjit Singh in his campaigns against the Afghans and had come out of retirement to fight in the war, although he had counseled against a war with Britain. In command of the center of the entrenchment was Mehtab Singh, while the right was commanded by Attar Singh and French Colonel François Mouton. As this was the weaker side of the entrenchment, 200 camel-borne swivel-guns were placed there. To bolster their defenses, the Sikhs had positioned 67 guns throughout the entrenchment.

Advancing Like Silent Demons

When the fog finally lifted, the British artillery opened up. The Sikh guns quickly responded, and for two hours both sides blasted away at each other with shot and shell. Despite the amount of lead being fired at them, little damage was done to the Sikh guns, although a few Sikh trenches and foxholes received direct hits. Overall casualties were not heavy. The Sikh gunners did little damage to the British guns, although they did manage to hit a cart carrying ammunition to a British mortar, which in turn caused the cattle pulling it to stampede.

By 9 am, the British heavy guns were out of ammunition. An officer was quickly sent to Gough to inform him of the fact. “Thank God!” replied Gough, adding, “Then I’ll be at them with the bayonet!” When Hardinge’s aide-de-camp, Lt. Col. Richard Benson, delivered a message urging Gough to call off the attack, the old Irishman spluttered in fury: “What! Withdraw the troops after the action has commenced and when I feel confident of victory? Indeed I will not!“ He ordered Dick’s division forward at once.

British horse artillery galloped ahead to cover the advance of Stacey’s brigade. The British and Indian troops steadily moved toward the Sikhs’ right in perfect silence. The artillery supporting them pushed to within 300 yards of the enemy entrenchment and began hammering away at it. A small Sikh cavalry detachment rode out to threaten the flank of the 53rd Regiment of Stacey’s brigade. Steady musket fire from the regiment’s flank company, along with artillery fire, quickly drove off the Sikh horsemen.

Onward Stacey’s brigade went, with Wilkinson’s brigade following close behind. The Sikh troops facing them fired into the advancing British and Indian troops. Gaps in the line appeared, but the troops kept coming. With a loud shout, the British and Indian troops charged the Sikhs and poured over the six-foot-high entrenchments. A Sikh gunner noted later: “When we attack, we begin firing our muskets and shouting our famous war-cry; but these men advanced in perfect silence. They appeared to me as demons, evil spirits, bent on our destruction. Who could withstand such fierce demons, with those awful bayonets, which they preferred to their guns?”

Breaching the Sikh Entrenchments

Sikh gunners to the right of Stacey’s brigade fought back with enfilading fire. Wilkinson’s brigade arrived just in time to help Stacey’s men. The 10th Regiment from Stacey’s brigade and the 80th Regiment from Wilkinson’s brigade quickly captured and silenced the annoying enemy batteries, but not before Dick was killed by a grapeshot round to the stomach.

Alarmed at the British and Indian breach of their entrenchments, a large number of Sikh troops broke cover and counterattacked Stacey’s and Wilkinson’s men, pushing them back. Ashburnham’s reserve brigade dashed into the fray. The Sikhs managed to drive the 3rd Division out of the entrenchment and recapture their guns, but in doing so they inadvertently had weakened the rest of the lines.

While the bloody Sikh counterattack was going on, Gough ordered Smith and Gilbert to make a diversion against the rest of the Sikh entrenchments. This had little effect. Reasoning that most of the Sikh troops were fighting the 3rd Division, Gough now ordered a general attack on the whole enemy position. Smith’s prone troops were ordered to their feet and began to advance against the Sikh left. Penny’s brigade led the way, covered by artillery fire and supported by Hicks’s brigade.

The attacking troops had difficulty keeping their footing in the rough terrain. The Sikhs poured a withering fire into the British troops, causing them to fall back. Hicks’s brigade opened its ranks to allow the retreating infantry to pass through, then reformed again and pressed forward. Hicks’s British, Indian, and Gurkha regiments were also met with a hail of bullets. Penny’s men rallied, and with the combined weight of the two brigades the British troops eventually took the entrenchment in front of them, climbing onto each others’ shoulders to stab and slash at the Sikhs lining the walls above them.

Smith’s division slowly pushed back the Sikh defenders, although enemy gunners somehow managed to swivel some of their guns behind Smith’s troops and fire into them. The 50th Regiment of Hicks’s brigade had to turn back around and recapture the guns, despite losing all of its officers above the rank of lieutenant in a matter of 10 minutes. The regiment’s commander, Lt. Col. Thomas Ryan, was one of the casualties.

Charge of the Light Dragoons

In its attack on the Sikh center, Gilbert’s 2nd Division had a tough time of it. The troops had trouble crossing the dry river bed and then found the entrenchment’s walls too high to climb without ladders. Three separate assaults were repulsed, and Gilbert and MacLaren fell wounded. To make things worse, Sikh cavalry galloped out and killed 29 of the retreating soldiers in full view of their comrades. The British troops finally captured the entrenchment a little to the east, where the walls were a little lower.

The troops of Dick’s 3rd Division, meanwhile, rallied and recaptured their sector of the entrenchment. Enduring intense enemy fire, sappers blew gaps in the entrenchment, allowing British cavalry to pass through single file. Once inside the entrenchment, the cavalry reformed and charged the Sikh gunners, cutting them down. A squadron of Lt. Col. Michael White’s 3rd Light Dragoons dashed through the breach, with the 8th and 9th Bengali Horse Artillery coming in on the Sikh right where the fortifications did not reach all the way to the river. Private John Pearman of the Light Dragoons matter of factly described the charge: “On we went by the dead and dying, and partly over the poor fellows, and up the parapet our horses scrambled. One of the Sikh artillery men struck at me with his sponge staff but missed me, hitting my horse on the hindquarters, which made the horse bend down. I cut a round at him and felt my sword strike him but could not say where, there was such a smoke on. I went with the rest through the camp at their battalions which we broke up.”

With pressure coming at them from three sides, the stubborn Sikh infantrymen were slowly driven back. Tej Singh, by this time, had fled the battlefield with an escort of horsemen. He had spent the morning in a personal bomb shelter constructed for him in the rear by his engineers. He galloped partly across the bridge, then stopped and inexplicably had one of the pontoon boats sunk. The damaged bridge would make retreat difficult for his soldiers still fighting for survival on the south side of the river.

10,000 Sikhs Killed or Wounded

Gough’s troops continued to push back the Sikhs, capturing their inner defensive lines and pouring volley after deadly volley into them as they fell back toward the Sutlej. As the Sikh troops crowded along the riverbank, British and Indian soldiers continued to hammer them with musket and artillery fire. In desperation, a few Sikhs attempted to charge, only to end up dead at the ends of bayonets. Sham Singh, more valorous than his counterpart Tej Singh, led another counterattack but fell mortally wounded by seven bullets.

Sikh soldiers desperately clambered across the damaged bridge, which collapsed under their weight. The Sutlej was alive with struggling men, camels, and horses. Other Sikh soldiers attempted to swim the rain-swollen river with little success. The British brought their guns down to the riverbank and poured shot and shell into the mass of Sikhs thrashing in the water. By 10:30 am the slaughter was over.

It had been a catastrophic day for the shattered Sikh army. The Sikhs suffered about 10,000 killed or wounded. They also lost 67 guns and 19 of their standards. The Maharani and her henchmen had succeeded with their Machiavellian plan of using the British Army to destroy the power of the Khalsa for them. The British, by contrast, had suffered 2,283 casualties, including 320 killed—about one-seventh of the total forces engaged.

Truce With the British

The war would soon be over. Gough crossed the Sutlej and marched toward Lahore. Although the Sikhs still had a sizable number of troops, the leaders denied them ammunition and supplies. With permission from Maharani Jindan, Gulab Singh met with the British at Kasure on February 16 and signed a truce agreeing to all the British demands. On March 9 the terms were formalized at Lahore, with the Sikhs handing over a large tract of land between the Sutlej and Beas Rivers. As part of the treaty, the Sikh army was reduced to 20,000 soldiers and 12,000 cavalry, while all the guns used against the British were turned over to them. A British garrison would occupy Lahore for a year. The Sikh government also agreed to pay the British the equivalent of £1.5 million When the Sikhs were unable to pay the war reparations, the British seized Kashmir Province and sold it back to Gulab Singh for the very reasonable price of £750,000. He now had his independence from Lahore, while the Sikhs were losing theirs.

Despite criticism from many of his military peers for his heavy-handed tactics and unnecessarily high losses, Gough returned in triumph to Britain, where he was made a baron, viscount, and eventually field marshal. Both houses of Parliament formally praised the old war horse for his victory at Sobraon, which he took to calling “the Indian Waterloo.” His successor as commander in chief of the British Army in India, Sir Charles Napier, accurately read the Sikh mood after the war. The rank and file believed that their leaders had betrayed them, Napier said. He fully expected the fragmented Sikh army to unite again. Napier thought there would be another war with the Sikhs in year or two. As events would show, he was right.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments