By Pedro Garcia

On September 7, 1862, Colonel Walter Taylor of General Robert E. Lee’s staff wrote to his sister: “The Yankee papers of the 6th exhibit a gloomy picture for our enemy. Just now it does appear as if God was truly with us. All along our lines the movement is onward.” The colonel was correct in believing that the Confederacy was reaching its apogee. One week after Taylor’s letter, the Confederate Senate passed a resolution calling on President Jefferson Davis to reaffirm free trade on the Mississippi River, a move that, by bringing war to the doorsteps of Union voters for a change, it was hoped would persuade them to vote for less resolute candidates. The catch, however, was that these operations would have to produce tangible military results.

Yet despite various successes in the summer of 1862, the clock was already ticking for the Confederacy, compelling its military leaders to take unavoidable risks. The Southern states enjoyed the best odds they had faced since the opening months of the war, nearing the peak number of men they could field at any one time, while the North was just beginning to tap its potential. The 477,000 men the South had in the field in July and August represented 76 percent of the 624,000 of the North, giving it a disparity of slightly better than three to four. Confederate leaders also knew that President Abraham Lincoln on July 1 had called for an additional 300,000 three-year volunteers. When mobilized, this would increase the North’s total to 924,000 men, and tip the scales even more heavily against the South.

Even with the new volunteers, the North would still have mobilized scarcely 20 percent of its potential military manpower. The South, on the other hand, had already put in the field almost twice that proportion (39.8 percent) from its pool of white males between the ages of 18 and 45. Furthermore, the Union War Department, on August 4, had drafted an additional 300,000 men from the state militias for nine-month service. This would raise the odds against the South to nearly three to one. Confederate leaders could not have known that the Lincoln government was also fast approaching the decision to enlist African Americans as soldiers, but they clearly knew that the moment was ripe for aggressive military action.

Planning the Kentucky Campaign

The drumbeat for such action rolled with rapidity. On August 16, as Robert E. Lee planned to outflank Maj. Gen. John Pope on the Rapidan River in Virginia, fellow Confederate Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s vanguard crossed into Kentucky. On August 22, as Lee danced with Pope on the Rappahannock, Maj. Gen. William Loring, in West Virginia, sent Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins on an audacious cavalry raid to the Ohio River. On August 25, as Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson set out for Thoroughfare Gap, General Braxton Bragg put the columns of Maj. Gens. Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price in motion in western Tennessee. On the 28th, as Jackson fought the skirmish at Brawner’s farm, Bragg left Chattanooga for Kentucky. A surgeon in Bragg’s army wrote: “Our army is in fighting trim and Bragg is anxious to strike a blow, and will surely do it. I have strong hopes of watering my horse in the Ohio before long.” Finally, on the 30th, as Maj. Gen. James Longstreet smashed Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s flank on the plains of Manassas, Smith moved to confront Union forces at Richmond, Kentucky. England and France were seemingly as close as they ever would be to intervention on behalf of Southern independence. For one brief moment, the Confederate star shone brightly.

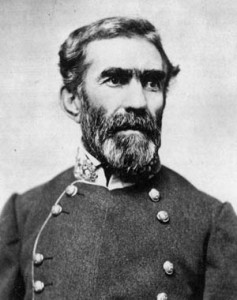

As director of major Confederate operations in the West, Bragg was in titular command of five of columns—his own, the armies of Van Dorn and Price in northern Mississippi, Smith’s column, and a smaller force in southwestern Virginia under Brig. Gen. Humphrey Marshall. In the meantime, Loring launched his own army, and a separate cavalry raid under Jenkins, to clear the mountainous counties of western Virginia. “Bragg ought immediately to advance,” the ever-aggressive Lee had written to Secretary of War George Randolph on June 19. Ten days later, Randolph ordered Bragg to “strike the moment opportunity offers.” On September 4, Davis, a good friend of Bragg’s, advised, “You have the field before you and I rely on your judgment.”

Preoccupied with focusing on the Union army of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, which had set out from Corinth, Mississippi, and was working its way eastward to Chattanooga, Tennessee, Bragg was never able to exert more than marginal coordination over his command. Even in Kentucky, the three armies of Bragg, Smith, and Marshall never physically united. In consequence, the grand Confederate offensive was a web of nearly random design held together by the most diaphanous of threads.

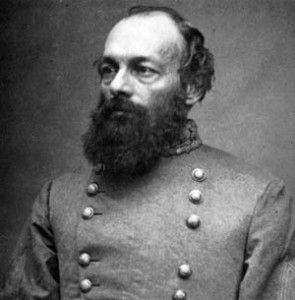

The plan called for Bragg’s 35,000-man army and Smith’s 18,000-man force to move in concert against Buell in middle Tennessee, and catch him in a pincers movement. After he was crushed, they would advance into Kentucky, being supported on their right flank by the forces of Marshall and Loring in western Virginia. As Bragg moved north through Tennessee and into central Kentucky, Smith would knock out a small Union post holding Cumberland Gap on the border of Tennessee and Kentucky. “The junction with Bragg if effected in time will I trust enable the two armies to crush Buell’s column and advance to the recovery of Tennessee and the occupation of Kentucky,” Davis wrote to Kirby Smith. For his part, Kirby Smith agreed to cooperate with Bragg. “There is yet time for a brilliant summer campaign,” he assured the other general. “I will not only cooperate with you, but will cheerfully place my command under you subject to your orders.” Unfortunately for the South, there would be no unified movement. The plan was weakened from the start by Bragg’s characteristic vacillation and timidity, coupled with Smith’s boldness and independent command. Neither was truly in command of the invasion.

Enthusiasm for the campaign was fueled by native-born Kentucky cavalry leader John Hunt Morgan, who asserted that central Kentucky was riddled with secessionist feeling. “I am here with a force sufficient to hold the country outside Lexington and Frankfort,” Morgan reported. “These places are garrisoned chiefly with home guards. The ridges between Lexington and Cincinnati have been destroyed. The whole country can be secured, and 25,000 to 30,000 men will join you at once.” Smitten with “Kentucky fever,” as he put it, Smith made an alternate proposal to march directly on Lexington. The proposal drastically changed—indeed undermined—the original plan he and Bragg had agreed upon. Surprisingly, Bragg, who could have stopped him early on, acquiesced enthusiastically. The ensuing campaign was to become one of the war’s most glaring examples of what can happen when command is not unified and there is no clearly defined military objective.

“The People are Bitterly and Violently Opposed to Us”

Marching out of Knoxville on August 14, the Confederates entered Kentucky without significant opposition. A foot soldier observed in his diary: “And now we have crossed Tennessee and have advanced 50 miles into Kentucky without firing a gun at Yankees. I certainly expected we would encounter Buell and have one desperate battle before leaving Tennessee, but that gentleman seems to have taken wings and left the country in double quick time.” Electing to bypass the Union garrison at Cumberland Gap, Smith’s army passed through gaps in the mountains west of the fortified place.

Plunging deeper into the Bluegrass State, the Confederate force found it to be in the midst of a devastating three-month drought and the countryside as “poor as Job’s turkey.” Contrary to Morgan’s boasts, the locals viewed secessionists with hostility. Typical of their attitude was the response one of Smith’s troopers received from a Kentuckian sitting on a porch. “Where does this road go?” inquired the cavalryman. “Don’t go nowhere, dammit, it stays right here,” he was told. Many Kentuckians were unenthused by the Confederates’ arrival. One unwelcoming citizen described them as “ragged, greasy and dirty, and some barefoot and looked more like the bipeds of pandemonium than beings of this earth. They surrounded our wells like the locusts of Egypt and struggled with each other as if perishing with thirst, and they thronged our kitchen doors and windows, begging for bread like hungry wolves.” The Confederate commander put it succinctly in a letter to his wife. “The people are bitterly and violently opposed to us,” wrote Smith.

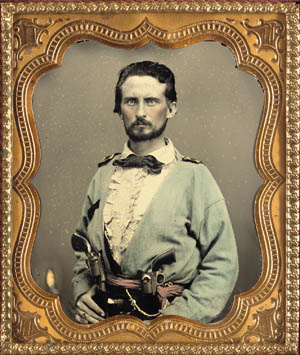

Smith had four divisions under him. Three of them, commanded by Brig. Gens. Thomas J. Churchill, Patrick R. Cleburne, and Harry Heth, contained about 3,000 men each. The remainder of the army (9,000 men)—about the same size as the Union garrison at Cumberland Gap—was organized in one large division under Brig. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson. Unwilling to leave such a large force in his rear unattended, Smith left Stevenson behind to keep an eye on the Federals. By August 26, the divisions of Cleburne and Churchill had started north toward Richmond and Big Hill, while Heth’s remained near Stevenson to await reinforcements and the army’s wagon train.

It was a terrible march, the roads winding through almost impassable mountains in ankle-deep dust. The weather was dry, with temperatures in the 90s, and water was almost unobtainable. The infantry quickly outdistanced its supply wagons and had to live off the countryside as best they could. Yet Confederate morale remained high, and the two lead divisions completed the march in three days. Smith’s unilateral thrust into central Kentucky wrested control of the campaign away from Bragg and made it doubly difficult to coordinate movements. With Smith so far north of him, Bragg moved out of Chattanooga, feinted toward Nashville, and moved north into Kentucky along the Louisville and Nashville railroad. Outflanked, Buell’s Army of the Tennessee was obliged to do likewise.

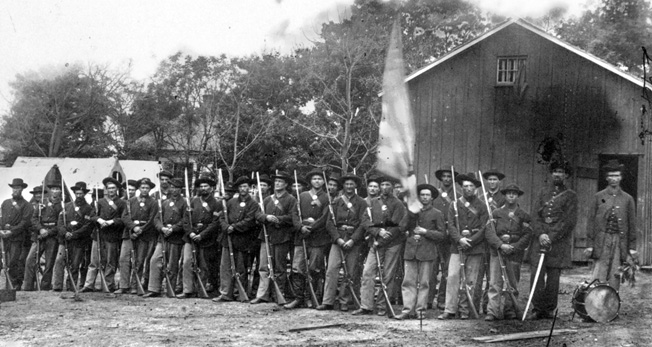

Bull Nelson’s Green Recruits

Meanwhile, a growing collection of men comprised almost entirely of green troops—6,500 men in two divisions styled rather grandly the Army of Kentucky—was assembled and placed under the command of one of Buell’s division commanders, Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson, a native Kentuckian whose headquarters were at Lexington. Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright of the Department of the Ohio had little confidence in the new recruits, telling leaders in Washington, “If you say go, they go, but I shall not expect success except by chance.” Wright believed the Kentucky River offered the most favorable terrain to set up a line to meet the advancing Confederates, and with that in mind he ordered Nelson to Lexington. With formidable granite bluffs that rose from the water literally at a 90-degree angle, Nelson was advised to make the river his line of defense.

Temporarily in charge of the green recruits until Nelson arrived was Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, who would later become famous for writing the biblically inspired novel Ben Hur. Smith’s intended target remained unclear, so Wallace advanced some troops and artillery to the Kentucky River, while dispatching others south to Lancaster and Richmond. Union cavalry was sent to scout below Richmond toward Kingston and Big Hill.

On August 24, Nelson arrived in Lexington and relieved Wallace. It soon became apparent that he had his own ideas. A loud, brassy, profane soldier who had served in the Navy in his youth, Nelson was disdainful of the opinions and feelings of others. He was determined to fight Smith south of the Kentucky River line, forwarding forces from the river to Richmond. Nelson kept some troops in Lexington and moved others to Lancaster and Danville, west of Richmond, to threaten Smith’s flank if he ventured farther north. Nelson also ordered three infantry regiments and artillery to move from Nicholasville to join the five regiments already in Richmond. His plan, he said, was “to mass the troops, knowing that the enemy would not cross the Kentucky River while 16,000 men were on their flank.” He scorned Smith as “a much smaller potato than I took him for.”

Kirby Smith on Big Hill

When Smith entered Kentucky, his cavalry screened his movements and scattered several Union units along the way. On August 23 at Big Hill, they captured a wagon train headed to Cumberland Gap from Richmond, utterly routing its green and panic-stricken escort. The victorious Southern troopers rode on to Richmond and demanded its surrender. Unable to force the issue when their demand was refused, the horsemen withdrew to Big Hill to wait for Smith. Union cavalry, on the 25th, was sent west and south of Big Hill on a reconnoitering mission to see if they could learn something of Smith’s location and intentions. By the evening of the 28th, they were able to report a growing Confederate strength in the Big Hill area. From that point on there would be a serious breakdown in field intelligence that jeopardized Nelson’s plans. The report was forwarded to Nelson in Richmond, but the cavalry was unaware that he had just left for Lexington. Consequently, he never saw the report, and it is reasonable to assume that had he known that Smith was concentrating near Big Hill, he quite probably would have reunited his badly divided forces the next day.

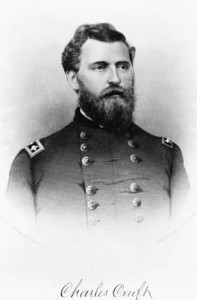

The regiments in Nelson’s Provisional Army of Kentucky were organized into two brigades commanded by Brig. Gens. Mahlon Manson and Charles Cruft. Both men had commanded brigades in Nelson’s former division in Buell’s army. Both men were political appointees with no combat experience, and neither man had confidence in his troops. Cruft could have been speaking for all eight regimental commanders when he expressed the view, “It was a sad spectacle for a soldier to look at these raw levies and contemplate their fate in a trial at arms with experienced troops.” He further lamented that his troops “could but indifferently execute some of the simplest movements in the manual of arms.”

The lack of any telegraph line between Lancaster and Richmond left Nelson without direct contact with his other forces in Lancaster and Danville, so he left Manson in command at Richmond in his absence, instructing him to remain where he was rather than starting west to join his planned concentration at Lancaster. In this manner, Nelson compounded his error of remaining below the Kentucky River. The next day, Nelson telegraphed Wright that “Kirby Smith’s game is now clear. He will assail Buell in left and rear.” Nelson now concentrated his total force, including troops from the Department of the Ohio and central Kentucky, 16,000 men in all, southwest of Richmond at Lancaster. If Smith moved back toward Buell in Tennessee, Nelson reasoned, he would be on Smith’s flank. If Smith moved straight up toward the Bluegrass region of Kentucky, he stood in his path. Given the information he had, the speculation was reasonable and sensible—but it was wrong.

Manson’s Strike on the Advancing Confederates

August 29 saw the Confederates complete a grueling three-day march that pushed the limits of human endurance. “Ragged, bare footed, almost starved, marching day and night, exhausted from want of water,” Smith wrote. “I have never seen such suffering, and there is not a complaint, not a murmur. Such fortitude, patriotism, and self control has never been surpassed by any army that ever existed.” Marching on nearly impassable roads, in a drought-plagued country, the Confederates penetrated deeply into Kentucky and reached Big Hill, 16 miles south of Richmond. In the van was Cleburne’s division, with Churchill’s division stretched out behind him on the Richmond road. The cavalry, scouting well beyond the infantry, had been in constant contact with the enemy for the last six days, and had kept Smith informed of the gathering forces around Richmond, far below the strong line of the Kentucky River.

Driven by the thought that the enemy force of green levies was largely unaware of the strength or speed of his advance, Smith was champing at the bit for a fight. If they had known his strength, he later wrote, they would have “opposed us in the passes and strong positions of the Cumberland mountains, or would have posted themselves along the high bluffs and precipices of the Kentucky River, where they could have resisted the passage of even a greatly superior force.”

That morning Union cavalry had stumbled onto the Confederate advance and sent back a report to Manson, who was camped a few miles away, that reached him at 11 am. The report was then forwarded to Nelson who, in another striking failure of field intelligence, did not see it for nearly 16 hours. Three hours after Union troopers sent the first report to Manson, they sent a second one informing him that 4,000 to 5,000 Confederates were advancing in earnest. “The only question for me now to determine was whether I should allow the enemy to attack me in camp, or whether I should advance to meet him,” Manson recalled. “To retreat would be to be considered a coward, dismissed in disgrace.”

A ridge dominated the high ground 1½ miles south of his position, and Manson feared that the Confederates would occupy it if he did not. Disregarding Nelson’s instructions to stay where he was, Manson aggressively pushed his brigade forward to occupy the high ground, and almost immediately his artillery drove off the probing Confederate cavalry. In fact, advancing with surprising ease, Manson’s van was able to capture a handful of prisoners and some horses as well as a few cannons. Union artillery continued to keep Confederate horsemen at bay, and by nightfall he had advanced farther south along the ridge to the sleepy hamlet of Rogersville. Feeling good about his prospects, Manson went into camp after pushing forward his cavalry.

That night, Smith became convinced that his proper course of action was to march on Lexington; he ordered Cleburne to attack the next morning. Smith had reached that conclusion because of a clash of arms that occurred that evening. Shortly after Manson had thrown his cavalry forward to reconnoiter, they encountered Confederate horsemen who were chased pell-mell back to Cleburne’s carefully deployed lines. Volleys of gunfire erupted that tore into the ranks of the Union troopers, who were driven as badly as they had been at Big Hill. That ended the day’s fighting, and Manson sent word to Cruft at Richmond to be ready to march to his support in the morning.

Manson’s Miscalculations

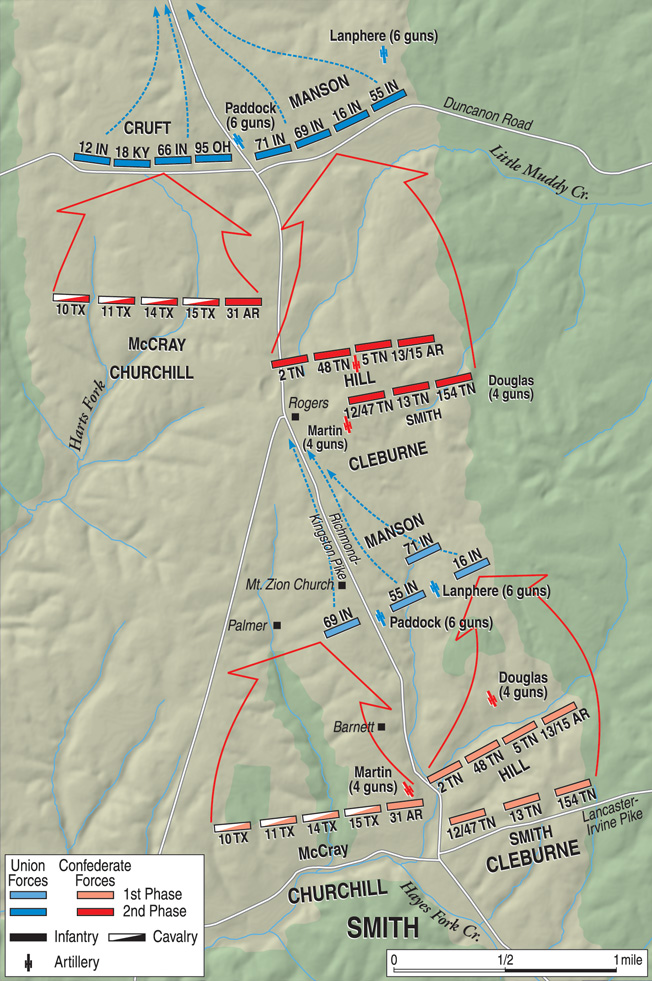

In the predawn darkness the next morning, Manson’s troops fixed their coffee and stumbled about trying to find water for their canteens. It was not long before scouts detected Cleburne’s division marching north through the village of Kingston. After dispatching orders to Cruft to join him, Manson immediately deployed his brigade one mile beyond Rogersville just south of Mount Zion Church. The Union troops would establish themselves in a defensive line on either side of the church, which was on high ground facing the Richmond road, and about 5½ miles below Richmond. The 55th Indiana was deployed east of the road, the 69th west of it, the 71st behind the 55th in reserve.

Before long, the Union artillery unlimbered and began to rake the head of Cleburne’s column. Cleburne responded to this destructive fire by deploying his division east of the Richmond road and the Irving-Lancaster Pike, which ran east and west just north of Kingston. He also put his own artillery on the front line, employing them in a methodical counterbattery fire, directing them to fire slowly and not waste a round. Indeed Cleburne, who was in command pending Smith’s arrival, aggressively sought to bring the fight to the enemy by maneuvering his division into an extended line beyond the Federals’ eastern flank.

Kirby Smith told Cleburne to delay the bold flank attack, advising him not to advance on Manson’s strong position until Churchill’s brigades arrived on the scene. Once in position, one of Churchill’s brigades would hit Manson’s right flank, while Cleburne advanced east of the road against the Union center. Colonel Preston Smith’s brigade would be held in reserve to exploit any breakthrough, or slide off to the east and hit Manson’s left flank—exactly the scenario Manson most feared. That fear would drive him to make a series of calamitous miscalculations. The last of Manson’s four regiments, the 16th Indiana, arrived in the midst of the furious artillery duel. The 16th was put front and center between the 55th and 69th Indiana Regiments. In effect, the Union left flank had been extended beyond Cleburne’s right.

Cleburne’s Blueprint For Victory

About 10 am, the leading brigade of Churchill’s division, under Colonel Thomas McCray, began arriving in the woods east of the Richmond road, and soon a very spirited exchange of small-arms fire erupted. The skirmish convinced Kirby Smith and Cleburne that Manson was planning to turn the Confederate right. Cleburne countered by moving the 154th Tennessee, the regiment that held the extreme right of Preston Smith’s reserve line, forward and east to extend Hill’s line. As McCray’s brigade deployed in the vicinity of Mount Zion Church preparing for their advance on the Union right flank, Manson remained convinced that the true threat was to his left flank. He responded by sending his reserve regiment, the 71st Indiana, as well as seven companies of the 69th Indiana that had been posted on the right flank, to support his left. Only three companies of the 69th remained on the right to confront McCray’s brigade, now forming to attack.

A hot skirmish erupted along the whole front of Manson’s line east of the Richmond road, as the 55th, 16th, and 69th Indiana advanced to within 100 yards of Confederate line. This, in turn, provoked an immediate response from Cleburne, who dispatched Colonel Lucius Polk’s 13th and 15th Arkansas Regiments to the support of the 154th Tennessee on the eastern flank. When far enough into the woods, Polk’s men would be at a 90-degree angle to the end of Manson’s line. It had become evident to Cleburne that the enemy “had staked everything on driving back or turning our right flank and that they had weakened their center to effect this object.”

Still unaware of McCray’s impending attack, Manson, by overloading his left had triggered the response he feared the most, an attack against that portion of his front. Furthermore, a trick of the terrain led him to make a series of tactical blunders. From his position with the 55th Indiana behind and in center of the Union line, he could not have possibly seen McCray’s column approaching his right flank. Less than a quarter of a mile west ran a creek known as Hayes Fork, and a mile beyond it was a big cornfield, north of which a ravine cut beyond his right flank, none of which was visible to him. Proceeding cautiously through a cornfield and a ravine, the Confederates exploded like a thunderbolt on the few Union troops who could not see them coming either. As McCray hit the right at the church, Preston Smith’s brigade nimbly executed Cleburne’s wishes by forming a 90-degree angle to Manson’s left, achieving a deadly enfilade from which they unloosed massive volleys. The raw Federals quickly went to pieces and began to dissolve into something close to chaos.

Meanwhile, Cleburne was preparing to personally lead Hill’s brigade straight ahead toward Manson’s center. As he rode over, Cleburne stopped to talk to Polk, who had been wounded, and was himself hit by a ball that took out four teeth and passed out his open mouth, depriving him of “the powers of speech, and this rendered my further presence on the field worse than useless.” By that point, Cleburne didn’t really need to talk. Despite the wound and his subsequent absence from the field, his earlier tactical dispositions had set in motion a bold blueprint for victory that was an early indication of the skills that would make Cleburne one of the Confederacy’s best battlefield generals. His maneuvering had brought much of his division into an extended line beyond the enemy’s eastern flank, and by observing that the enemy was reinforcing that flank, he correspondingly made plans to quickly strike at the exact point where Union troops were being removed.

“The Rout Had Become General”

Into the desperate situation Cruft’s brigade, with the 95th Ohio in the vanguard, began arriving on the field, marching at the double-quick from its camp site at Richmond. Colonel William McMillan, commanding the 95th, was directed to position the regiment on the right flank reinforcing three companies from the 69th Indiana and ordered to quickly charge a Southern battery that was unlimbering to support McCray’s advance against Mount Zion Church. The order should never have been given, and McMillan should have questioned it. With no time to deploy, the scattered regiment would have to advance squarely in front of McCray’s troops, which were then spilling out of the ravine toward the church.

The Confederates ripped into the Ohioans. “Whilst we were thus engaged,” reported McMillan, “the enemy advanced his right and left wings, outflanking and driving our forces before him. Seeing that it would be reckless and useless to continue our assault upon the battery, I ordered the regiment to halt and fall back, which they did, for a time, in good order, losing, however, in addition to our killed and wounded, 160 men and a large number of officers at this point.” Lt. Col. J.B. Armstrong, who assumed command when McMillan inexplicably left the field, had a different version. Armstrong claimed that McMillan’s actual order was, “Every man to save himself”—beginning with McMillan. Armstrong put the number of men captured at 200.

As Manson recalled tersely, “The rout had become general.” Next up was the 18th Kentucky, establishing a line behind which the bloodied 95th and Manson’s broken units could reform. In the face of the persistent Confederate advance, the 18th bravely stemmed the tide. Yet after a short time the regiment retired with severe losses. Cruft commended the 18th for having prevented the retreat from becoming a rout but acknowledged that “the panic was well-nigh universal. The whole thing was fast becoming shameful.”

The 12th and 66th Indiana were left of Cruft’s brigade, and these troops were moved back two miles in the rear of the original battle line in a attempt to rally the rest of the command. Cruft cobbled together a new line west of the Richmond road, and Manson’s shattered regiments formed east of the road, not far from where Manson’s infantry had driven off Confederate cavalry the previous afternoon.

As Manson and Cruft were watching the Confederates forming to advance on the new line, a courier arrived from Lexington and handed Manson an order from Nelson—a directive that should have been sent two or three days earlier. It instructed Manson not to fight at Richmond but instead to march west to Lancaster. Nelson had sent the order 10 hours earlier, at 2:30 am, in response to the cavalry report the previous day.

Nelson’s Arrival

Within minutes, the confident Rebels, intent on finishing the battle, advanced on McCray’s column. Spearheading the drive toward Cruft’s position, Preston Smith moved on Manson’s position. When they were within 400 yards, a Union battery of six guns belched canister, followed rapidly by volleys of musketry, “the most incessant firing of cannon and musketry I have ever heard,” reported McCray. Cruft’s troops fought with astonishing determination to check the Confederate assault. Nevertheless, the butternuts pressed forward until they reached a thickly overgrown fence about 200 yards from Cruft’s line. McCray, finding the air literally filled with canister and minie balls, ordered his troops to lie down under cover.

Emboldened by their defense and perhaps thinking the tide had shifted to them, the Union forces counterattacked. When they had closed to within 50 yards, McCray gave the order to rise and fire. A terrific storm of bullets buzzed through the air like angry insects knocking down men with fearful effect, driving the Federals back “in the wildest confusion and disorder.” Confederates up and down the line relentlessly pushed forward, both Union brigades melting away before them. The second Union battle position had been broken, and as Manson and Cruft worked furiously to regain and retain unit cohesion, they determined to make another stand on the southern outskirts of Richmond, at the city cemetery.

As the new position was being organized, sudden cheers erupted that signaled the arrival of the army’s commanding general. No doubt some who cheered him soon regretted it, as the enraged Nelson attempted to restore order by beating soldiers over the head with the flat sides of his sword. Words were exchanged between Nelson and Manson when they met on the field, and Nelson later bitterly accused Manson of disobeying his order to avoid a fight and take the army to Lancaster. Now, Nelson, Manson, and Cruft managed to rally 2,500 troops on the crest of a low-lying ridge, where they deployed behind a stone fence and the tombstones of the cemetery. Meanwhile, Kirby Smith let his enervated Confederates rest for about an hour. By then, the fight had been going on for eight hours under a punishing sun and had covered miles of ground.

When reorganized, the plan of attack would go forward unchanged, strike the flanks, with Churchill advancing on the left and Preston Smith on the right. On the cusp of a complete success, Kirby Smith added a new wrinkle, sending his cavalry on a sweep around Richmond to cut off the expected Union retreat. At 5 pm he ordered a general advance. Union artillery opened first, firing shells and then canister at the disciplined Confederates. The soldiers waiting for Smith’s men were not quite as green as they had been earlier in the day. The pair of spankings they had received had quickly taught them a great deal about combat, and now they were delivering a withering fire and exacting a heavy price. A Southerner recalled that “we quickly formed our lines and moved on the cemetery, and in 20 minutes 140 men of the 2nd Tennessee and 128 of the 48th Tennessee were killed and wounded.”

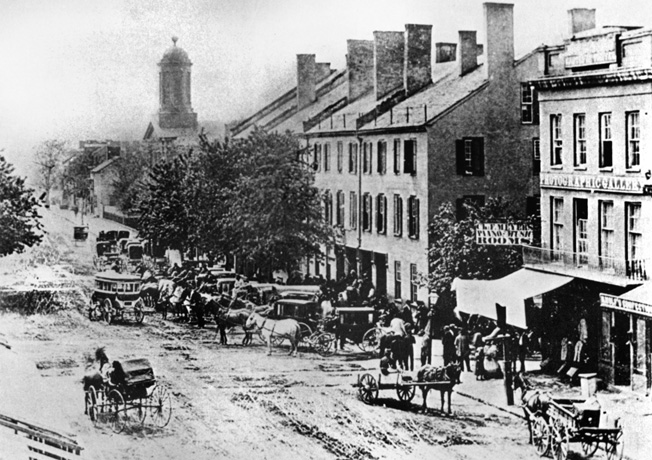

With the setting sun’s rays wreathed in sulfurous smoke, presenting a blood-red hue, Nelson rode among the troops, attempting to inspire them and threatening them with bodily injury if they failed to do their duty. Referencing his huge bulk, he shouted, “Boys, if they can’t hit something as big as I am, they can’t hit anything!” His personal entreaties worked and the Union line momentarily held firm. Within seconds, however, another deadly volley ripped into the Union lines, and those who were not killed or maimed broke for the rear. Nelson, who was struck by a pair of balls that smashed into his thigh, observed later that his troops “stood about 3 rounds, when struck by panic, they fled in disorder.” The panic-stricken mob that had been the Union army fell back in utter disorganization through the streets of Richmond and onto the Lexington road.

Kirby Smith’s cavalry was waiting for them. His troopers shot down a good many men, and by the hundreds they surrendered. One Confederate major wrote that the “havoc was frightful, and the Federals threw down their arms and surrendered in crowds, and of the few who escaped not one in ten carried his musket with him.” Concealing himself in a cornfield, Nelson managed to sneak away. There were so many prisoners that the cavalry commander could not give Smith an accurate estimate, he simply reported that he “had a ten acre lot full.”

The Battle of Richmond, Kentucky: Cannae in the Civil War

The Battle of Richmond could not truly compare with the numbers engaged at the ancient Battle of Cannae, yet the tactics and sheer onesidedness of the battle were eerily reminiscent of that earlier clash. The Union loss was 206 killed, 844 wounded, and 4,304 missing, with only between 800 and 900 managing to escape. Confederate losses were 98 killed, 492 wounded, and eight missing. Kirby Smith pushed on to occupy Lexington on September 2, where he wrote his wife: “I am well and have the most enthusiastic reception in Kentucky—the whole population is turning out in mass. Recruits are flocking to me by the thousands. All of Kentucky to the Ohio is at our feet.” Feverish enthusiasm abounded throughout the South. “We think we may safely say that the day of Kentucky’s deliverance from the hateful thrall of abolition despotism has brightly dawned,” wrote the Richmond Dispatch. Vast military opportunities did indeed lay before the Confederates, but it remained to be seen if they would reap the harvest.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments