By John Brown

The Gustav Line, stretching across Italy at its narrowest part between Gaeta and Ortona, was a formidable system of defenses, some of it in coastal marshes but mainly in mountainous country through which ran fast-flowing rivers. To the natural defensive advantages of the mountainous terrain the Germans had added extended and interlocking defensive positions reinforced with concrete and railway girders.

The defenses were multilayered, with positions planned from which to launch counterattacks on frontline areas lost to the enemy. Anti-personnel minefields and barbed-wire entanglements up to 400 yards deep covered the flats before hills and behind riverbanks. Batteries of guns, mortars, and machine guns covered every possible route of attack, and dams had been dynamited to flood low-lying lands already soggy from the winter rains. The Gustav Line was a prime example of German military engineering.

Monte Cassino: Linchpin of the Gustav Line

The key point in the line was the town of Cassino on the Rapido River. It lay astride Highway 6, the highway to Rome some 70 miles to the north, and was dominated by the huge, ancient Benedictine monastery atop the 1,700-foot massif of Monte Cassino. Saint Benedict founded the monastery in 529, and it became the home of the Benedictine Order. For centuries it was the leading monastery in Western Europe and a center of learning, particularly in the field of medicine. It was destroyed by Lombards in 580, by Saracens in 883, by Normans in 1030, and by earthquake in 1349, and rebuilt each time. The last time it was rebuilt as a fortress surrounded by 15-foot-high walls, 10 feet thick at their base, and was approached only by a five-mile-long twisting track. In 1886 it was declared an Italian national monument. Monte Cassino and its surrounding mountains were identified by the Italian military as the key defensive area to block an approach on Rome from the south, and the Germans were quick to take advantage of this in 1943.

On January 22, the Allies landed the U.S. VI Corps on the beach at Anzio, 40 miles behind the Gustav Line and some 30 or so miles from Rome. It was thought that this threat to the German rear and the German lines of communication would cause them to fall back. The VI Corps, made up of the 3rd U.S. and 1st British Infantry Divisions together with U.S. Rangers and British Commandos, landed unopposed, and its commander, Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, fearing a German trap, ordered his corps to dig in. The Germans quickly brought up reserves and cordoned off the beachhead.

In February, New Zealander Lt. Gen. Bernard Freyberg, commander of the 2nd New Zealand, 4th Indian, and 78th British Divisions, insisted that the Monte Cassino monastery be bombed as the Germans were using it as an artillery observation post.

This was not so. The Germans had said they would preserve the sanctity of the monastery and had in fact transported many of its priceless paintings, manuscripts, and sculptures to safety in the Vatican. But Freyberg persisted, and on February 15, more than 200 Allied bombers dropped 600 tons of high explosives on the monastery, devastating it. The only Germans in it were two military police guards. After the bombing, paratroopers of the 1st Parachute Division moved in and built the rubble into a formidable fortress.

Stalemates on the Front, Build-ups in the Rear

On the morning of March 15, another 775 Allied bombers dropped 1,250 tons of bombs on the already battered town of Cassino. Over half the paratroopers of the German 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Division, occupying the town, were killed, wounded, or buried alive in the raid. Like the monastery, the rubble of the town was built into a fortress.

By the beginning of May, both sides had fought themselves to exhaustion on the Gustav Line in three battles, the first from January 12 to February 9, the second from February 15 to 18, and the third from February 19 to March 23. The battles had been fought with murderous intensity in appalling conditions of bitter cold, snow, sleet, and rain. Casualties had been heavy, particularly on the Allied side.

During the stalemate from the end of the third battle and the date set for the opening of the fourth battle, May 11, the Germans, using Italian labor, continued strengthening the Gustav Line and worked on new fallback lines, the Hitler Line, later renamed the Dora Line, seven miles behind the Gustav Line, and the Orange Line. Another one, the C-Line, was designed as a last-ditch protection of the immediate approaches to Rome. Ten thousand Italians labored on building this line.

At the same time, the Allies were building up their forces and supplies for what would be an onslaught of overpowering numerical and material strength. Strict secrecy was observed during the buildup. The movement of tanks and vehicles and supplies to the front was carried out as far as possible at night, as was their dispersal and camouflage. Radio silence was enforced, and most of the troops who would be used in the offensive were kept well back from the front. Marine landings were practiced along the coast to give the Germans the impression the Allies were preparing for landings from the sea closer to or beyond Rome. The result of these and other measures was that the Germans were completely ignorant of the Allied buildup and the date, place, and strength of the offensive.

Opposing Plans

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring was in overall command of German forces in Italy. At Anzio he had General Eberhard von Mackensen’s Fourteenth Army surrounding the American VI Corps, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott. At the Gustav Line was General Heinrich von Vietinghoff-Scheel’s Tenth Army made up of two corps—Lt. Gen. Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin’s 14th Panzer Corps and General Valentin Feuerstein’s LI Mountain Corps, which included Lt. Gen. Richard Heidrich’s 1st Parachute Division. Kesselring also had three panzer and two infantry divisions at various points between the Gustav Line and Rome, held in reserve against a possible sea landing or airborne attack.

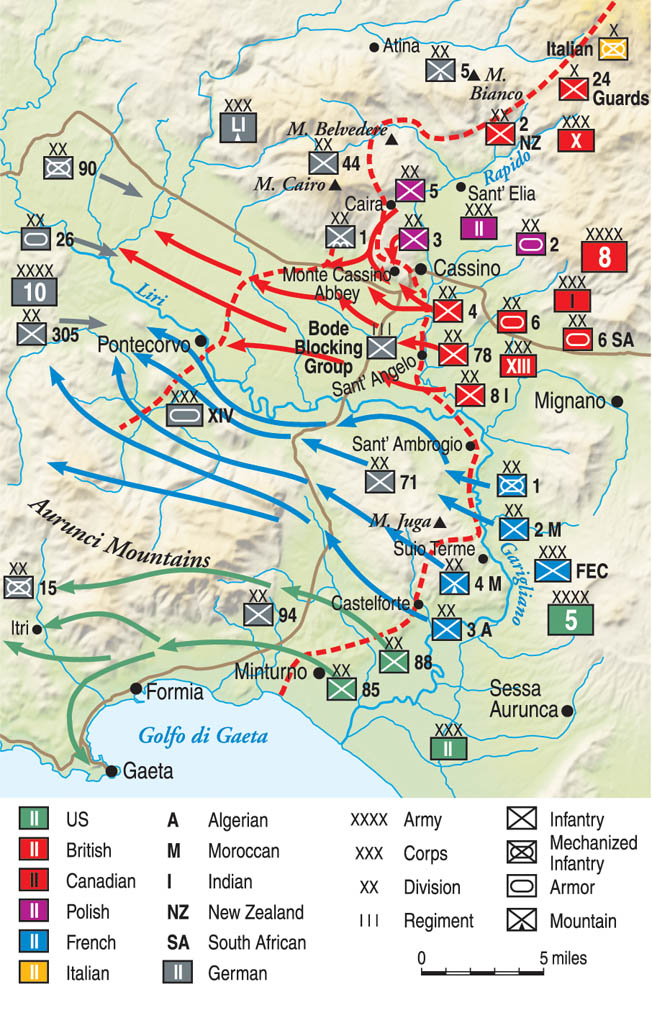

The overall commander of Allied forces was British General Sir Harold Alexander. His basic plan for the fourth battle of Cassino, codenamed Operation Diadem, was fairly straightforward and depended upon sheer numerical and matériel superiority. The main thrust would be by the British Eighth Army commanded by General Oliver Leese. It would cross the Rapido River and enter the Liri Valley where the British 4th and Indian 8th Infantry Divisions would create a bridgehead that would be exploited by the powerful British 78th Division and Canadian 5th Armored Division, with the British 6th Armored Division in reserve.

The right flank of this force would be covered by the two infantry divisions and an armored brigade of Lt. Gen. Wladyslaw Anders’s Polish II Corps attacking the German paratroopers on Monte Cassino and on the left flank by the II Corps of American Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army, which included General Alphonse Juin’s French Expeditionary Corps of four divisions of Moroccan and Algerian troops and some 9,000 Goumiers who would attack up the Ausente Valley toward Ausonia and Esperia while the Americans attacked along the coast. The Goumiers were Moroccan irregular troops who were already well known for their combat prowess in mountainous country. At Anzio, the Allied divisions contained in the beachhead by the Germans would break out and head for Valmontone, where they would cut Highway 6 and help encircle and destroy the German Tenth Army retreating from the Gustav Line.

General Alexander’s objective was the complete annihilation of German forces in Italy. Rome, for him, had no military significance; it would fall in good time. But publicity-conscious Clark, whose Fifth Army was responsible for Anzio and the Cassino front from the Liri River to the sea, had his own objective—the capture of Rome and the glory he thought would go with it.

On May 11, the Allies had 108 battalions facing 57 German battalions, and many of the German battalions were only about half strength. The Allied advantage in infantry was at least three-to-one, and they had assembled 1,600 guns, 2,000 tanks, and 3,000 aircraft, equal to 45 guns, 57 tanks, and 85 aircraft for every 1,000 yards of the front.

The Assault Begins

At 11 pm on May 11, a massive Allied artillery barrage deluged every known German battery and defensive position along the 20 miles of the Garigliano-Rapido line, signaling the beginning of the fourth battle of Cassino. It was at least a week before Kesselring expected an attack, and its time, place, and power caught the Germans off guard. But they reacted quickly. Forty minutes after the barrage started, it stopped, and the Allied divisions began to move forward.

The American 85th and 88th Divisions on the left flank of the line moved first, pushing westward, with the 351st Regiment of the 88th detailed to capture the village of Santa Maria Infante. Forty minutes later, the four Free French divisions began their drive into the Aurunci Mountains, and five minutes later again and to the right of the Free French the British 4th and Indian 8th Divisions lowered their assault boats into the fast-flowing Rapido River. At 1 am on May 12, the Polish Corps launched its attack on the high ground around the Cassino monastery. Two hours after the barrage started, the Allies and the Germans were locked in combat all along the 20-mile front.

Crossing the Rapido

On the vital Rapido River front, German guns, mortars, and machine guns opened up on the troops of the 1st Royal Fusiliers as they tried to get their boats on the river. Many died before they could get in the boats, others died as they tried to cross, and some fell in the river and drowned, pulled down by the weight of their full battle kits. Some of the boats were swept away by the fast current.

The troops who did get across ran into intense fire. Some connected with trip wires that set off smoke canisters or activated machine guns firing on fixed lines. The smoke mixed with river mist to create a thick fog, adding to the confusion and disorganization. But the troops did manage to establish a bridgehead among the minefields and barbed wire, finding cover in drainage ditches or under or behind anything that provided shelter from the shells and machine-gun bullets.

The other leading battalion was the 1/12th Frontier Force Rifles, an Indian battalion that crossed the river downstream of Sant’ Angelo with the objective of, together with the Royal Fusiliers, encircling the village. But many of their boats were destroyed or swept downstream. Finally they got across to face machine guns and mines and smoke and fog. Like the Fusiliers, they were pinned down in drainage ditches for the rest of that night and the following day.

As soon as the first troops were across the Rapido, work began on three bridges over the river, preparations for which had been made during the previous nights. Access roads had been made to the river and camouflaged, engineers had swum the river and worked on landing points on the other side, and now the prefabricated parts of the bridges were brought up.

Fog and the heavy shelling hampered work on the bridges. Damage to one of them was so severe it had to be abandoned, and because of the urgency to get tanks across the river, work was concentrated on one bridge, nicknamed Amazon. Despite several daring attacks on the bridge by German aircraft, a superhuman effort costing 83 casualties out of the 200 soldiers who worked on the bridge permitted the tanks of the 17/21st Lancers to begin crossing under a deluge of fire at 9 the next morning. They drove over the bodies of the soldiers who had died on the far bank during the night; they could not avoid them. The opening of this bridge was the turning point of the battle opposite the Liri Valley.

Repulsed from the Monastery

Perhaps the hardest task of all was that of the Polish II Corps—to capture the monastery fortress on Monte Casino. The monastery was linked with tightly integrated strongpoints and fire plans that covered all approaches, and General Anders’s assault was planned to take on all of the key German positions simultaneously to avoid flanking fire.

The Poles attacked with reckless gallantry, the Carpathian Division attacking Hill 593 as well as along the gorge between Snakeshead and Phantom Ridges, while the Kresowa Division attacked the strongpoints at the end of Phantom Ridge. With these cleared, the way to the Liri Valley behind the monastery would be open and the monastery itself isolated.

The Carpathians attacked against an increasing volume of fire and through minefields and barbed wire. By the sheer ferocity of their attack, they took the summit of Hill 593 at about 2:30 am. With their communications shot to pieces, they pressed on toward Hill 569. But the German paratroopers counterattacked, driving them back to Hill 593, where the counterattack was held. Another German attack half an hour later was driven off, and another a short time afterward.

The Germans had gotten close to the Polish positions and had found cover from where they began sniping and bombarding the Poles. This continued all day, and when night fell the paratroopers attacked again under a mortar bombardment. After a bitter hand-to-hand fight the few surviving Poles, an officer and seven men, were forced to retreat. In the gorge between Snakeshead and Phantom Ridges, the Poles came under murderous machine-gun and mortar fire, and gunfire and mines destroyed the tanks supporting them one after another. Their attack was brought to a halt.

Meanwhile, three battalions of the Kresowa Division attacked up Phantom Ridge toward Sant’ Angelo, their objectives were Hills 575 and 505. Here, too, they ran into heavy fire from numerous German bunkers and dugouts situated in cavities and depressions in the rocky ground. A few Polish troops reached the top of Phantom Ridge and became involved in vicious hand-to-hand fighting with the German paratroopers before being compelled to halt only halfway to their objectives at the end of the ridge.

Then the paratroopers bracketed the whole of the eastern face of Phantom Ridge with artillery and machine-gun fire, and by 3 am all three Polish battalions were pinned down. A fourth battalion was sent in to try to get the attack under way again, but it was hopeless. At first light the paratroopers counterattacked but were fought off. The Poles’ communications had broken down, and commanders had no contact with the troops.

Both Polish divisions had sustained such heavy casualties that General Anders had no alternative but to call off the attacks and order the troops back to their starting lines. He was distraught. Some 800 German paratroopers had driven off attacks by battalion after battalion of his two divisions with very heavy casualties, and Monte Cassino seemed as impregnable as ever. He immediately began planning another attack.

The Bringing Down the British “Battleaxe”

On the first day in the American sector nearest the coast, the 85th Division managed to secure only one of its objectives before being pinned down. On the 88th Division front, two battalions of the 350th Regiment made good progress on the first night, capturing the southern part of Monte Damiano, but the 351st Regiment failed to take its objective, the village of Santa Maria Infante. Under heavy fire in the darkness and mist, several company commanders had been killed, and control broke down. The commander of the 2nd Battalion, Lt. Col. Raymond Kendall, quickly reorganized his battalion and personally led it in an attack until he was shot in the head and killed. Despite receiving heavy air support during the day, the 88th “Blue Devil” Division made little progress in the first 36 hours of the assault.

To the immediate right of the Americans, the French North Africans, preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment, had more success. A Moroccan battalion quickly captured the key Monte Faito, giving them vital artillery observation, but elsewhere minefields and gunfire broke up many of the attacks. Failure to capture one mountain meant failure all along the front as the intact defensive positions brought down fire on its flanks. There was little forward movement that first day, and the casualties were very high.

Downstream of the British 4th Division sector, the Fusilier battalion of the 8th Indian Division attacked the high ground before the village of Sant’ Angelo; then the Gurkha battalion attacked the village itself, which was taken at high cost. Canadian tanks moved in behind the village. Some German troops, seeing their stronghold of Sant’ Angelo fall, surrendered. Others retreated.

On the night of the 13th, the first units of the powerful British 78th “Battleaxe” Division entered the line in the 4th Division sector, and the 8th Indian Division’s reserve brigade joined in the fighting behind Sant’ Angelo. Tanks crossing the Amazon bridge made for the Cassino-Pignataro road, while the 12th Infantry Brigade pushed forward with fixed bayonets and the 10th Brigade wheeled northward toward Route 6. By the 14th, a bridgehead of 3,000 yards had been established, and more bridges had been thrown across the Rapido.

The battle now became one of attrition as the British overran Cassino town and slowly battered their way into the Liri Valley. German planes dive-bombed and strafed them, and the German troops opposing them fought superbly.

Fighting for the Liri Valley

One of the key features of the planned drive up the Liri Valley was that the Eighth Army should advance quickly enough to trap the bulk of the German Tenth Army against the sea, the trap being fully sprung when the VI Corps out of Anzio slammed the back door on the Germans at Valmontone. But the strength of the Allies in the Liri Valley built up quickly to five divisions—the British 78th, 8th Indian, 6th British Armored, 1st Canadian Infantry, 5th Canadian Armored—and together with their tanks, self-propelled guns, half-tracks, some 2,000 supply trucks, and hundreds of other vehicles the congestion was too much for the valley to take. Progress slowed to a crawl with movement held up by huge bottlenecks, traffic jams, and confusion.

On the 13th on the American front, the 88th Division continued trying to move up the road to capture the village of Santa Maria Infante against intense German fire. As the day wore on, the road became clogged with tanks and vehicles, and at 5 pm all traffic on the road ground to a halt. Then the German artillery opened up, disabling tanks and setting fire to vehicles.

It was a bad day for the Americans. One whole company surrendered after being surrounded. The inexperience of both officers and men resulted in heavy losses, and Santa Maria Infante remained in German hands.

On the 13th the French North Africans resumed their attack, their objective to exploit the only success of the previous day by driving from Monte Faito to Monte Maio. After a heavy bombardment the Moroccans moved forward and, bunker by bunker, drove the Germans off successive heights until they took Monte Maio, the heights of which commanded the southern part of the Liri Valley. The Germans began to fall back, hounded by gunfire directed from Monte Maio. Meanwhile, down in the Garigliano Valley, the North Africans, using rocket launchers and machine guns, smashed their way through lines of pillboxes and other fortifications. By the next day, Castelforte had fallen to them and the Gustav Line was cracked.

Then, General Juin, rather than consolidating, unleashed his mountain troops, including several thousand Moroccan Goumier irregulars, into the trackless mountains. They advanced at astonishing speed, driving the German forces before them. With the southwestern flank of the Gustav Line smashed and the speed of the following attacks, the Germans were not able to hold the Hitler Line in the coastal sector.

On the morning of the 14th, the Americans found that the Germans on the high ground around Santa Maria Infante had gone; they were retreating to keep in contact with their left flank which was reeling back from the French attack. The Americans moved forward with only rear guards, mines, and booby traps to impede their progress.

This breakthrough of the Gustav Line made the German position in the Liri Valley much more difficult. On May 16, General Oliver Leese, commander of the Eighth Army, ordered the 78th Division to cut Route 6 behind Cassino. At the same time the Polish Corps tried again to take the monastery fortress on Monte Cassino.

German Withdrawal from Monte Cassino

Every night since the failure of their attack on Monte Cassino on the 12th, the Poles had sent patrols in among the German positions on the mountain, keeping the German paratroopers bloodshot eyed from lack of sleep. They had followed up with artillery barrages on the German positions. One paratrooper later said that the stench of the dead on the mountainsides was so horrible they had to wear their gas masks.

On the night of the 16th, a Polish patrol succeeded in taking out several of the paratroopers’ advance posts around Hill 593. General Anders quickly fed a whole battalion into the position. The German paratroopers counterattacked furiously in a battle fought with bayonets, grenades, and submachine guns throughout the 17th. It was another bloodbath, but the Poles held on. Both sides had fought themselves to exhaustion. There were now only about 200 paratroopers left in the monastery area; one of their companies had only one officer, one NCO, and one soldier fit to fight.

Operationally, the battle was unnecessary as the main advance up the Liri Valley was bypassing the mountain and the abbey fortress could simply have been contained. But General Anders ordered an all-out assault the next morning, the 18th.

By then, however, Field Marshal Kesselring, seeing the hopelessness of trying to hold on to what remained of the Gustav Line, ordered a withdrawal to the Hitler Line. The paratroopers reluctantly had withdrawn from the abbey during the night, taking as many of their wounded with them as they could. The Poles walked into the dusty rubble the next morning, and at 10:30 they raised a Polish flag above the ruins.

Advancing on Rome, not the Germans

The U.S. Fifth and British Eighth Armies were now moving up the coastal plain and the Liri Valley with the German rear guards trying to delay them to give themselves time to occupy the Hitler Line. The French were moving so fast that they had to wait for the British to catch up. Now, General Alexander told General Truscott at Anzio, was the moment to make a determined effort to break out of the beachhead and head for the Alban Hills to block the retreat of the German Tenth Army.

The breakout from Anzio was launched on May 23, at the same time as Canadian troops, after fierce fighting, broke through the Hitler Line between Aquino and Pontecorvo. The breakout was successful, but two days later General Clark diverted troops away from closing the trap on the retreating German Tenth Army in order that he and his troops would have the glory of being first to enter Rome.

Troops of the U.S. 88th Division did enter Rome on June 4, and General Clark made his triumphal entry on June 5. It was his day of glory. He had a large “Roma” sign taken down and shipped home, and his huge publicity entourage let the world know of his victory. But his diverting troops away from closing the trap that his commander, General Alexander, had planned for the Germans allowed much of the Tenth Army to escape and retreat in good order to fight again.

General Clark’s day of glory was just that. On June 6, the Allies invaded Europe at Normandy, and news of D-Day relegated Italy to the back pages.

“Cassino: The Hollow Victory”

Military historians have little good to say about the Italian campaign in general and the battle for Cassino in particular, except for the successful deception prior to the fourth battle for Cassino and the great achievements of the French Expeditionary Corps. One historian calls it “a campaign which for lack of strategic sense and tactical imagination is unique in military history,” while another named his book Cassino, The Hollow Victory; there are others who claim that the campaign should never have been started or that it should have been curtailed at a certain time. All seem to agree that victory at Cassino was simply the result of the Allies’ sheer weight of men and matériel.

The battle for Cassino, variously described as an abattoir, a vision of hell, and a slaughterhouse, was all of these and more for the soldiers who fought and died in it. Casualties during the fourth battle for Cassino were: British Eighth Army, including British, Canadians, Poles, Indians, and Gurkhas—10,919 plus a large but unknown number unaccounted for, and U.S. Fifth Army, including Americans, British, and French—34,014.

For the whole of the Cassino-Rome campaign, casualties were approximately 105,000. German casualties were thought to be at least 80,000.

The Gustav Line had been breached, and the Eternal City had become the first Axis capital to fall to the Allies, but months of heavy fighting remained in Italy, the strategic value of which is still being debated to this day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments