By Michael D. Hull

Short, slightly built, baby-faced, and soft-spoken, Audie L. Murphy of Texas was far removed from the popular image of a warrior or hero.

When he tried to enlist for service early in World War II, he was initially rejected by both the Army and the Marine Corps, and yet he went on to become America’s most decorated soldier in history. In a span of less than two years, his fighting spirit, leadership qualities, and courage under fire made him a living legend in the martial tradition of Sergeant Alvin C. York, General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., and Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller.

The young man who would earn no less than 28 medals and citations, including the pale-blue ribbon of his country’s highest honor, sprang from the most humble origins. Born on June 20, 1924, into a sharecropper’s family near the small town of Farmersville in northeastern Texas, Audie Murphy was the seventh of 12 children. He grew up in extreme poverty. In school, his classmates nicknamed him “Short Breeches” because his only pair of pants had shrunk from relentless washing.

Audie’s father, Emmett Murphy, hired himself out to farmers, working on the local onion and cotton crops, and the boy joined him as soon as he was able to do so. Life was hard, and food was scarce. Audie’s quiet, sad-eyed mother, Josie Bell Murphy, toiled endlessly both indoors and in the fields. The family moved frequently in search of work and finally settled a few miles away in the little Hunt County community of Celeste.

The Murphys lived for a time in a converted railroad boxcar on the edge of town before moving into a rundown house. Because he was needed to help earn money, young Audie had to neglect his education. He quit school after completing the fifth grade. He was nine years old.

The boy loved to hunt in the local scrubland. Blessed with sharp eyesight, quick reflexes, and a determined personality beneath his mild demeanor, he displayed uncanny accuracy with a rifle and was able to bag rabbits and squirrels for the family table. He was a natural marksman. These traits would serve him well later.

Restless and despondent about the hard times as the Great Depression gripped the nation, Emmett Murphy deserted his family several times, and in 1940 he left for good. Audie observed wryly, “My dad wasn’t lazy; he just had a genius for not considering the future.” A few months later, the boy suffered the most heart-rending experience of his life when his beloved mother died of a heart disease on May 23, 1941. Always close to her, he mourned for several months. Most of his siblings disappeared into orphanages as Audie spent several teenage years in casual labor – selling newspapers, picking cotton, and working in a filling station, a grocery store, and a radio repair shop.

He became keenly interested in military matters after listening to stories related to him by two uncles who had soldiered in France in 1918, and the boy often told friends that he wanted to enlist. Besides the possible adventure and glory it promised a youth, the profession of arms meant escape from grinding rural poverty. So, when the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, plunged America into World War II, Audie Murphy, now 17 years old, trudged off eagerly to a recruiting station.

His ardor was quickly dampened. Standing only five feet, five inches tall and weighing just 110 pounds, he was rejected by Marine Corps and Army airborne recruiters. But he was undeterred. On the advice of one of the recruiters, he went home and spent the next few months gaining weight with bananas and milk. Then, brandishing a letter from his sister attesting to his age as being 18, Audie presented himself to recruiters in Dallas and was accepted into the Army on June 30, 1942.

After 13 weeks of basic training at desolate Camp Wolters in Texas, during which he passed out while learning close-order drill, Audie was sent to Fort Meade, Maryland, in the late fall of 1942 for advanced infantry training. He adapted easily to Army life. Amid the camaraderie of barracks, mess halls, and pup tents, he felt he had finally found a home where he belonged. Because of his almost girlish features, he was nicknamed “Baby” by his comrades. An officer suggested that the unimposing youth become a headquarters runner rather than a rifleman, but he resisted stoutly. He was determined to prove himself in combat. He impressed his superiors with his bearing, leadership potential, and loyal attitude and was soon wearing the two stripes of a corporal.

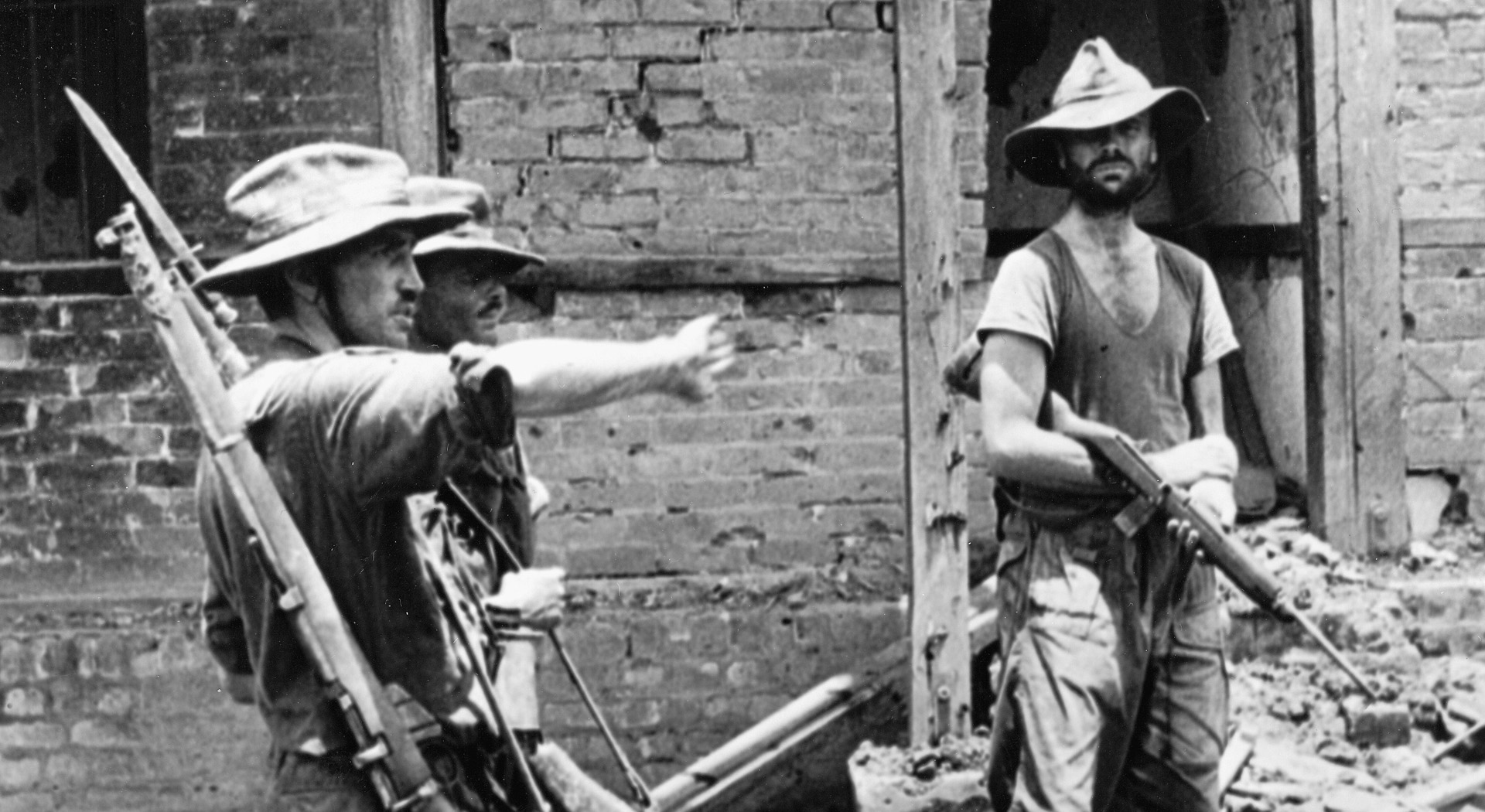

In February 1943, Murphy rode a troopship to North Africa and the start of a brief but unprecedented military career. In North Africa, he joined B Company of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, part of the proud 3rd “Rock of the Marne” Infantry Division of World War I fame. He would spend 28 months with the unit, though he had to wait for several months in North Africa before seeing action.

Audie’s introduction to war came early in July 1943, when the British Eighth and U.S. Seventh Armies invaded Sicily to dislodge the German and Italian defenders and push toward the key port of Messina, stepping stone to the Italian mainland. Audie’s regiment landed at Licata on July 10. The hard struggle to capture the dusty, craggy island dispelled notions that the young Texan had harbored earlier about war being adventurous or romantic; it was a matter of mountains, pack mules, lonely nights, hunger, thirst, and exhaustion.

But Audie, self-disciplined and no stranger to hardship, volunteered for patrols, was eager to take the point during advances, and demonstrated dexterity with weapons. He also exhibited early on a hard, matter-of-fact approach to infantry warfare that was uncommon among citizen soldiers. On one occasion, when he spotted two Italian officers escaping on white horses, he coolly shot them. Disturbed, his platoon leader asked him, “Why’d you do that?” Audie replied tersely, “That’s our job.”

Murphy was felled by malaria for several weeks in Sicily. When he recovered, he fiercely resisted efforts to send him as a replacement to another unit, and he rejoined his company at Salerno. The 3rd Infantry Division had landed there nine days after the British and American armies had gone ashore in Italy.

The division fought a series of actions around the Volturno River, and Audie soon found that if the Sicilian campaign had been bad, Italy was infinitely worse, with more mountains to climb, rainy days and cold nights, mud, and shells crashing down incessantly. He witnessed enough pain and death to last a lifetime. Out on patrol one dark night after a skirmish with German troops, Audie and his men took cover in an abandoned quarry. The enemy pursued them but were halted by American fire, which killed three men and caused the others to surrender. The action gained Murphy three stripes.

He and his comrades slogged up the Italian boot, through Mignano and Monte Lungo, and into the terrible Monte Cassino campaign. The doughty little Texan was never far from the front and became well known for enthusiastically venturing out alone to stalk and kill Germans wherever he could find them. He won his first Bronze Star for leading a night patrol to destroy with rifle grenades and Molotov cocktails a damaged German tank, which its crew was striving to repair.

Audie was the consummate infantryman. He handled small arms with assurance, and, unlike many citizen soldiers, did not hesitate to kill the enemy. Historian S.L.A. Marshall reported after World War II that a large percentage of American foot soldiers had seldom fired their weapons in action and rarely hit their targets when they did so. Murphy always fired and usually hit his target.

Although claiming to be as prone to fear as any of his comrades, Audie possessed tactical judgment that helped him to keep his nerve when others lost it. Despite his dearth of schooling, he had natural intelligence and a facility for assessing a combat situation. He said, “Experience helps. You soon learn that a situation is seldom as black as the imagination paints it. Some always get through.”

After another bout of malaria that sent him to a field hospital for 10 days, Murphy was offered a battlefield commission. But he declined it because he did not want to leave his company. Then, in January 1944, came the almost disastrous invasion at Anzio, where British and American forces were kept penned in the beachhead and pounded by German artillery and bombing for four months. Mere survival day by day was a victory for the hapless GIs and British Tommies at Anzio, and Audie Murphy watched many of his friends die there. He said ruefully, “I began feeling like a fugitive from the law of averages.” One of his friends, cartoonist Bill Mauldin, later incorporated the comment in one of his famous “Willie and Joe” drawings depicting the woes of U.S. foot soldiers in World War II.

Audie made it through the Anzio debacle unscathed, one of the few men in his company not to be wounded and awarded the Purple Heart. He was eventually the last of the 235 original members of his company to survive. A grave, solitary figure who seldom received letters at mail-call time, Audie was most at home with his comrades on the front lines. He was intensely loyal to his company. “As long as there’s a man in the line,” he said, “maybe I feel that my place is up there beside him.” He felt uneasy while on leave in Rome after the capital’s liberation by General Mark W. Clark’s U.S. Fifth Army on June 5, 1944. “We prowl through Rome like ghosts,” he reported, “finding no satisfaction in anything we see or do. I feel like a man briefly reprieved from death; and there is no joy within me. We can have no hope until the war is ended. Thinking of the men on the fighting fronts, I grow lonely on the streets of Rome.”

After the liberation of the Eternal City, the hard-fighting 3rd Infantry Division was pulled out of the line to retrain and re-equip for Operation Dragoon, the upcoming Allied amphibious invasion of Southern France between Toulon and Cannes. Bolstered with replacements, the division, now led by short, stentorian Major General John W. “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, landed on the beaches in the Bay of Cavalaire and at Pampelonne on August 15, 1944.

Audie Murphy’s B Company splashed ashore that morning near the town of Ramatuelle, south of St. Tropez. Three hours after crossing the beach and heading inland, the 1st Battalion, 15th Regiment was pinned down by a German machine-gun nest on “Pillbox Hill.” Audie’s company was moved forward from reserve to find a new line of approach, but it too was pinned down. So, on his own initiative, the little Texan crawled back downhill to the heavy weapons platoon, borrowed a .30-caliber machine gun, and scrambled back up the slope with his best friend, Private Lattie Tipton, to find a firing position. They swiftly killed two German defenders.

After exhausting their belt of ammunition, Murphy and Tipton charged and overran a German trench using carbines and hand grenades. When an enemy soldier in a nearby foxhole waved a white flag, Tipton carelessly rose to accept his surrender. He was shot dead. Enraged, Murphy grabbed an abandoned German MG-42 machine gun from the ground and charged along the hillside, firing from the hip and throwing grenades with his free hand. Alone, and shooting at anything that moved, he wiped out several enemy positions and killed five Germans, wounded two, and captured five. The rest of Audie’s unit, which had failed to support him despite his shouted curses, then moved up to occupy the ridgeline. The Texan’s gallantry earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, awarded on March 5, 1945. But it did not make up for the loss of his friend, Tipton. “I won the DSC,” he said, “but all he got was death.”

Supported by Free French and Resistance groups coming out of hiding, the American forces advanced swiftly up the Rhone Valley in the summer of 1944. For the men of the 3rd Infantry Division, the campaign was heartening after the hellish months in the interminable mountains and muddy valleys of Italy. “We experience great exhilaration,” reported Sergeant Murphy, “for there is nothing so good for the morale of the foot soldier as progress.” But, late in August 1944, a shell fragment nicked Audie’s heel and put him in a field hospital for two weeks.

In the fighting near Besancon on September 15, a German mortar round exploded near Murphy, killing two men nearby and sending him to a hospital for another week. He could not help wondering whether his luck was beginning to run out. By now, all of the men in his platoon with whom he had found comradeship in North Africa and Italy were either wounded or dead. The loss of comrades affected him deeply, and he resisted forging close relationships with their successors. He was perceived as a soldier fighting a war of his own.

Audie was also growing embittered. “So many men have come and gone that I can no longer keep track of them,” he lamented. “I have isolated myself as much as possible, desiring only to do my work and be left alone. I feel burnt out, emotionally and physically exhausted. Let the hill be strewn with corpses, so long as I do not have to turn over the bodies and find the familiar face of a friend.” He kept on fighting, and, like all of his comrades in the line, tried to stay alive day by day.

During the fighting around Cleurie on October 2, 1944, Audie unwittingly led a patrol into a German ambush. The GIs were pinned down by severe fire, so Murphy crawled around to a flank and charged alone against the enemy. Firing a Thompson submachine gun and tossing grenades, he wiped them out. He was awarded the prestigious Silver Star. Three days later, on October 5, several of Audie’s men were shot in a similar encounter. The gallant Texan stealthily worked his way forward until he could see the enemy positions and called down artillery and mortar salvos by radio. The Germans withdrew with heavy casualties, and Sergeant Murphy received an oak leaf cluster to his Silver Star.

Because of his courage and leadership, senior officers recommended Audie for a battlefield commission several times, but he always turned them down. He felt that his sparse education would preclude him from coping with the administrative duties of an officer. Also, the Army routinely rotated new officers out of their units, and Audie did not want to leave B Company. However, his battalion commander wangled a waiver on the rotation policy and assured Audie that he would receive help with his paperwork. So, Sergeant Murphy became 2nd Lieutenant Murphy on October 14, 1944.

Twelve days later, on October 26, he suffered his most serious wound of the war. While his unit was attacking through the Montagne Forest near Les Rouges Eaux, he was taken by surprise and shot in the right hip by a German sniper. Audie managed to kill his assailant, but he suffered intense pain for several hours before he could reach a field hospital. The wound turned gangrenous, and he had to endure two and a half dreary months of treatment and recuperation. Penicillin saved his life. He had plenty of time while in bed to indulge in the fatalism endemic to all infantrymen.

“These Krauts are getting to be better shots than they used to be, or else my luck’s playing out on me,” he noted. “I guess some day they will tag me for keeps.” After his recovery, Murphy could have gone home with his wounds and decorations. But his fighting spirit was undiminished.

The enemy was still fighting hard, and seasoned warriors like Audie Murphy were sorely needed on the front lines as the British, American, Canadian, and Free French Armies pushed, yard by yard and with heavy losses, toward the German border. So, after a well-deserved furlough in Paris, Murphy rejoined B Company on January 14, 1945. His most spectacular battlefield feat—the one that would earn him the coveted Medal of Honor—was yet to come.

The 3rd Infantry Division was getting ready for the push to the Alsatian city of Colmar in northeastern France, south of Strasbourg on the eastern slopes of the rugged Vosges Mountains. There, a German bridgehead west of the River Rhine intruded 80 miles wide and deep into the Allied lines. Eight enemy divisions, helped by a brutal winter, were preventing the French First Army—part of Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers’ Sixth Army Group—from reaching Colmar. A two-pronged French-American offensive was planned, starting on January 22, 1945, with the U.S. II Corps driving from the north and the French I Corps pushing from the south. The 3rd Division was spearheading II Corps.

On January 23, the 30th Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division had been ordered to clear a wooded area, the Bois de Riedwihr, on the outskirts of the villages of Holtzwihr and Riedwihr, but a German counterattack of at least 10 tanks and 100 infantrymen had decimated the 30th, which withdrew after its soldiers were unable to dig foxholes in the frozen ground.

Lieutenant Murphy’s battalion had moved out of reserve to follow lead units of the 3rd Division across several rivers and through forests toward Riedwihr and was ordered to take the Bois de Riedwihr the following day. When the 15th Regiment stepped off, the enemy fire was intense, and casualties mounted quickly.

When the Texan awoke early on January 25, he found his hair frozen to the side of his foxhole. That afternoon, he was wounded yet again when German mortar fragments bloodied his left leg. He bandaged it hastily and refused to go to an aid station. Nevertheless, by midnight on January 25 Murphy’s men had reached a position 600 yards deep in the woods just north of Holtzwihr. They tried to dig in, but the ground remained frozen.

“This night seemed unusually long, and the snow colder than I ever dreamed it could be,” Murphy later wrote. “The sound of picks on frozen ground beat against my eardrums like mad.”

When the commander of B Company was wounded early on the morning of January 26, Murphy assumed command. Every officer in Company B was dead or wounded except Murphy, and the company’s strength was depleted from 120 to only 18 effective riflemen. The lieutenant was concerned that his position might be overrun by a German counterattack.

Just after dawn on the 26th, a pair of M-10 tank destroyers from Lt. Col. Walter E. Tardy’s 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion arrived to bolster Company B’s precarious position. Murphy took advantage of the time he had and deployed one of the tank destroyers and five small armored vehicles of the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion on his right flank. The second tank destroyer took up a position 40 yards in front of the thin American line, and Company B made contact with Company A, 15th Regiment on its left. Murphy’s command post, in a drainage ditch just forward of the first tank destroyer, maintained radio contact with battalion headquarters a mile to the rear.

By early afternoon, expected reinforcements from the 2nd Battalion, 30th Regiment, still had not arrived in support, but Murphy’s orders were to hold the position until reinforced.

Just as the 15th Regiment was getting ready to push forward near Holtzwihr on January 26, the enemy launched an armor-infantry counterattack. Around 2 PM that day, Murphy and his men saw six big Mark VI Tiger tanks and more than 200 German infantrymen coming toward them. These Germans were later identified as men of the 2nd Mountain Division, transferred from Norway to the Colmar area recently and trained in winter combat.

Audie shouted to his men to prepare for action. In front of him, one of the tank destroyers tried to move into a firing position on the icy ground but slid into a ditch. Its crew scampered to the rear as the Germans advanced toward Murphy’s position, attempting to cut the road from Holtzwihr and threaten the entire 3rd Division position.

Spreading a map in front of his foxhole, Murphy called on a field telephone for artillery support. The 90mm shells from the tank destroyers did not deter the German tanks as they rolled relentlessly forward.

“I saw the enemy tanks get direct hits,” Murphy remembered, “but the rounds proved ineffective against the heavily armored German tanks. Advancing and firing viciously, they knocked out a Company B machine-gun crew. Then the rear tank destroyer was hit by an 88mm shell that pierced its thin armor and killed the commander and gunner. The surviving crew members scurried out and retreated into the woods.”

American artillery shells crashed down, killing German soldiers in the open. Murphy called in coordinate corrections to the artillery battalion, and shells continued to kick up showers of snowy dirt among the enemy force, hurling bodies in all directions. But the German tanks lumbered on, untouched.

The situation seemed hopeless for the Americans. How were 18 riflemen expected to stop a German armored task force? Murphy told his platoon sergeant, “Get the men back—I’m going to stay here with the phone as long as I can.” The sergeant was reluctant to leave him alone. “Get the hell out of here!” yelled Audie. “That’s an order!” Hesitantly, the sergeant took his men back deeper into the cover of the woods 200 yards to the rear, and the resolute Texan faced the oncoming enemy alone.

With the German troops now only 200 yards away, Audie shouted into the field telephone, “Let’s have some artillery!” Then he fired his M-1 carbine until the ammunition ran out. The Germans came on. Murphy was desperate, but then he noticed that on the hull of the still-burning tank destroyer was a .50-caliber machine gun, loaded and idle. It was his only chance. Dragging his telephone line behind him, Audie ran to the TD and clambered aboard. After pulling the dead commander out of the way, he started firing at the enemy troops.

His bullets could have no effect on the Tiger tanks, but he hoped that the loss of their infantry support might drive them off. As he fired the machine gun, Murphy kept calling for artillery fire to knock out the tanks. After calling in a correction to coordinates, the voice on the other end of the line asked, “How close are they to you?” The Texan answered drily, “Just hold the phone and I’ll let one talk to you.” He swung the .50-caliber gun from side to side and fired repeatedly. Germans crumpled in the snow.

Enemy rounds rocked the tank destroyer, which could have blown up at any instant, and Audie almost fell off twice. But he caught himself and kept firing. Swirling smoke from the burning TD gave him cover. He called for more artillery fire, and shells plowed up the ground 50 yards in front of him. By now, most of the Germans lay dead or wounded.

“I loved that artillery,” Murphy wrote. “I could see Kraut soldiers disappear in clouds of smoke and snow, hear them scream and shout, yet they came on and on as though nothing would stop them.”

One group of German infantrymen got to within 10 yards of Murphy’s position aboard the flaming tank destroyer. He saw them just in time and shot them down in the snow.

Miraculously, the Tigers started to withdraw. Audie called in a final coordinate correction. “Correct fire,” he shouted, “fifty over!” The voice on the line warned, “That’s right on your position.” Jumping from the TD, Audie replied, “Let her go—I’m leaving!” His leg wound from the previous day started bleeding as he limped hurriedly back toward the woods. The tank destroyer finally blew up in a ball of flame, and the concussion sent Murphy sprawling in the snow. Scrambling on, he soon rejoined his company. Singlehandedly, he had turned back an armored force and saved his men from annihilation.

The little unit regrouped in the woods and then cleared the area of Germans. The next day, B Company fought its way into Holtzwihr, and the town was captured by 10 AM. Murphy took part in the subsequent weeks of action to clear the Colmar Pocket of the enemy. The city itself fell to the Allies on February 8. Promoted to 1st lieutenant eight days later, Audie was assigned to battalion headquarters for several weeks and was not with his company when it advanced across Germany and into Austria. He would resume command of B Company late in May 1945.

For his heroism in the Holtzwihr woods, Murphy was recommended for the Medal of Honor. He wrote home, “Since that is all the medals they have to offer, I’ll have to take it easy for a while.” After a furlough in Paris, he spent several weeks serving as a liaison officer while the European war waned. His superiors did not want to risk sending him back on the line. Audie was dismayed but found excuses to explore the forward areas.

The high point of Lieutenant Audie Leon Murphy’s military career came on June 2, 1945, when Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, commander of the U.S. Seventh Army, placed the pale-blue ribbon of the Medal of Honor around his neck at a ceremony near Salzburg, Austria. His citation read in part: “…His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he killed or wounded about 50….”

In addition to his nation’s highest honor, the Texan had earned the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star with oak leaf cluster, the Legion of Merit, the prized Combat Infantryman’s Badge, the Bronze Star with cluster, a Purple Heart with cluster, the Presidential Unit Citation, the French Fourragere, the French Legion of Honor, the Croix de Guerre with Palm and Silver Star, the French Liberation Medal, the Belgian Croix de Guerre with Palm, and campaign ribbons—28 medals and citations in all. He had spent 400 days on the front lines in Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany, and was officially credited with having killed, wounded, or captured 240 enemy soldiers. And he had saved the lives of many of his own men. Yet he was still too young to vote.

America’s most decorated serviceman flew home from Paris on June 10, 1945, to national adulation. Everywhere he went, people sought him out to shake his hand, and some wept when they met him. When he stepped into a barber shop to get a haircut, fascinated bystanders gathered outside and peered through the window. In his home state, Audie was welcomed back with parades and banquets, and his photograph was hung at the state capitol in Austin. The threadbare sharecropper’s son was now a national figure—shy, diffident, and uncomfortable with all the attention. And he was weary.

Deficient in schooling and skills suitable for the civilian world, Audie wondered what to do with the rest of his life. He suffered persistent pain from his hip wound, and an application to the U.S. Military Academy was turned down. So an Army career was ruled out, and he was discharged on September 21, 1945.

It was a photograph of the smiling, baby-faced war hero on the cover of the July 16, 1945, issue of Life magazine that opened a path to opportunity for Audie Murphy, though he was ill equipped for it.

That path led to Hollywood, thanks to legendary screen star James Cagney. When the two men met, Cagney, who was exactly Murphy’s height, exclaimed, “Dignity from within, not the kind imposed on you from without! Spiritual overtones. He looks like Huckleberry Finn grown up. No, not really grown up. There’s something in those eyes that is as old as death and yet as young as springtime.”

Acting like a father, the celebrated actor put the young veteran on a salary and personal contract and tried to turn him into an actor.The Texan bunked in the star’s pool house for a year while the groundwork was laid for his new career. The association with Cagney led to a screen test, a series of minor film roles, and a three-year marriage to Wanda Hendrix, a comely starlet from Jacksonville, Florida.

In July 1950, the month after the outbreak of the Korean War, Murphy returned to Dallas to join the 36th Infantry Division of the Texas National Guard. But he did not go to Korea. His final rank later was major in the Texas Guard.

Audie Murphy made a total of 44 feature films, most of them low-budget westerns, in the 1950s and 1960s. His first and most effective starring role was that of a frightened Union Army soldier in John Huston’s critically acclaimed Civil War film based on the classic Stephen Crane story The Red Badge of Couragein 1951. The cast included Audie’s wartime friend, Bill Mauldin.

With the aid of ghostwriter Spec McLure, Audie published his memoir, To Hell and Back, in 1949—a simply told, forthright, and sometimes harrowing record of World War II from the foxhole perspective. “The main reason that I wanted the book to be written was to remind a forgetful public of a lot of boys who never made it home,” Audie explained. “The present tense was chosen for the book because in a combat man’s life there is little left but the present tense. It was my purpose to tell the story as simply and honestly as I could, avoiding heroics because I do not believe in heroics. The great man of the war to me was the little fellow who did what was asked of him and paid whatever price that action cost.”

When a screen version of the book was later made in Hollywood, with Audie Murphy uneasily portraying himself, he cringed at Universal Studios’ poster hype: “Just a kid too young to shave…but old enough to win every medal his country had to give!” Audie was outspokenly critical of the film, which he considered a glamorized betrayal of the dogface foot soldiers among whom he had served. He fought to get the bowdlerized script toughened, depicting the squalor, pain, and sorrow of war. But he failed. Released in 1955, directed by Jesse Hibbs and costarring Marshall Thompson, Charles Drake, and Jack Kelly, To Hell and Backwas a sprawling action film marred by a static, clichéd script. It proved to be Universal’s top-grossing picture for two decades.

Shortly after divorcing Wanda Hendrix, Murphy married Pamela Archer, a vivacious airline stewardess and fellow Texan, in April 1951. They had two sons, Terry Michael and James Shannon, whom the war hero adored. Meanwhile, he wrote poems and the lyrics for 16 country-and- western songs. The most popular, Shutters and Boards, written with composer Scott Turner in 1962, was recorded by several artists, including Dean Martin and Porter Wagoner. Another song, When the Wind Blows in Chicago, was recorded by Eddie Arnold. Audie also raised thoroughbred horses, became a Shriner, and worked on behalf of troubled children.

But success in Hollywood had turned sour for Audie Murphy. Public interest in westerns flagged in the late 1950s and 1960s, and his box-office appeal faded. He gambled heavily and unluckily, became involved in a number of unsuccessful business ventures, and went bankrupt in 1968. Two years later, he was acquitted of a murder charge after beating up a man in a barroom brawl. Increasingly troubled by his battlefield experiences, Audie had frequent nightmares, was plagued by insomnia and depression, and slept with a pistol under his pillow. He got hooked on prescription drugs, and adverse publicity about his woes drove him into seclusion. He gave away his medals, and when the Army replaced them, he gave them away again.

Eventually, Audie tried to pull himself together and became a representative for an investment group. He planned a business trip that he hoped would put him back on his feet. On May 28, 1971, he flew with four other people in his light plane from Atlanta, Georgia, to Martinsville, Virginia, to visit a prefabricated housing plant. Late that morning, the plane crashed in rain and fog near the tiny town of Galax in southwestern Virginia. There were no survivors.

Flouting the wishes expressed in Murphy’s 1965 will that his burial be simple and non-military, America’s World War II hero was laid to rest with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery on June 7, 1971. His gravesite, near the amphitheater, is the second most visited year-round; only President John F. Kennedy’s grave draws more visitors.

Meanwhile, schools, hospitals, highways, and Army clubs were named in honor of Audie Murphy; statues of him were erected in San Antonio and Greenville, Texas; he was inducted posthumously into the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City; then-Governor George W. Bush of Texas proclaimed June 20 as “Audie Murphy Day” in 1999, and the war hero was pictured on a 33-cent postage stamp in 2000.

Audie Murphy is a tragic figure in the pantheon of American heroes. Reared in hardship and less than a success in civilian life, he is remembered for his valor in the war against fascist tyranny. But the shadowy demons of the battlefield continued to stalk him, and he found no peace until death.