By Robert Barr Smith

Just boys facing danger, please God make them men;

If they live through the danger, make them boys once again.

—Sergeant Ginger Woodcock, June 5, 1944

On the morning of June 6, 1944, the greatest amphibious fleet in history bore in toward the coast of Normandy. In spite of the enormous power of the aviation and naval assets supporting the landing, in spite of the strength of the Allied divisions poised to come ashore, the success or failure of Operation Overlord depended heavily on several much smaller actions. Among these were three critical missions assigned to the British Airborne, all designed to seal off the invasion beaches from German interference from the east.

The British and Canadian invasion forces were slated to land over 18 miles of beach west of the coastal town of Ouistreham. Just to the east, the Caen Canal and the Orne River found their way into the English Channel. And about three miles farther eastward a heavy German battery frowned down from the high ground at a place called Merville. Farther still to the east lay the mouth of the Dives River.

First, the invasion plan required the destruction of the five Dives River bridges, blocking the path of German armor counterattacking from the east against Juno and Sword Beaches. Second, glider-borne British paratroops would land almost on top of the Orne River and Caen Canal bridges at Benouville; they were to carry and hold the bridges at all costs, preserving the way eastward for British formations coming off the beach. Third, long before daylight a British para battalion would land to destroy the heavy German artillery battery at Merville.

The battery was a vital position. In the days before the invasion, German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had done his best in the time he had to fortify this whole coast. He had planted thousands of mines and beach obstacles and flooded miles of fields along the Dives Valley. Many of the usable fields bristled with stakes as a defense against gliders. In the spring of 1944, he stood on the high ground east of the mouth of the Orne, looking westward down the line of beaches. Inland lay the ancient city of Caen, now headquarters to the 13,000-man German 716th Infantry Division. And on the east bank of the Orne, a little inland, lay the site of the Merville battery. This ground, Rommel said prophetically, was the key to the gateway to France and, ultimately, to Germany.

It would be.

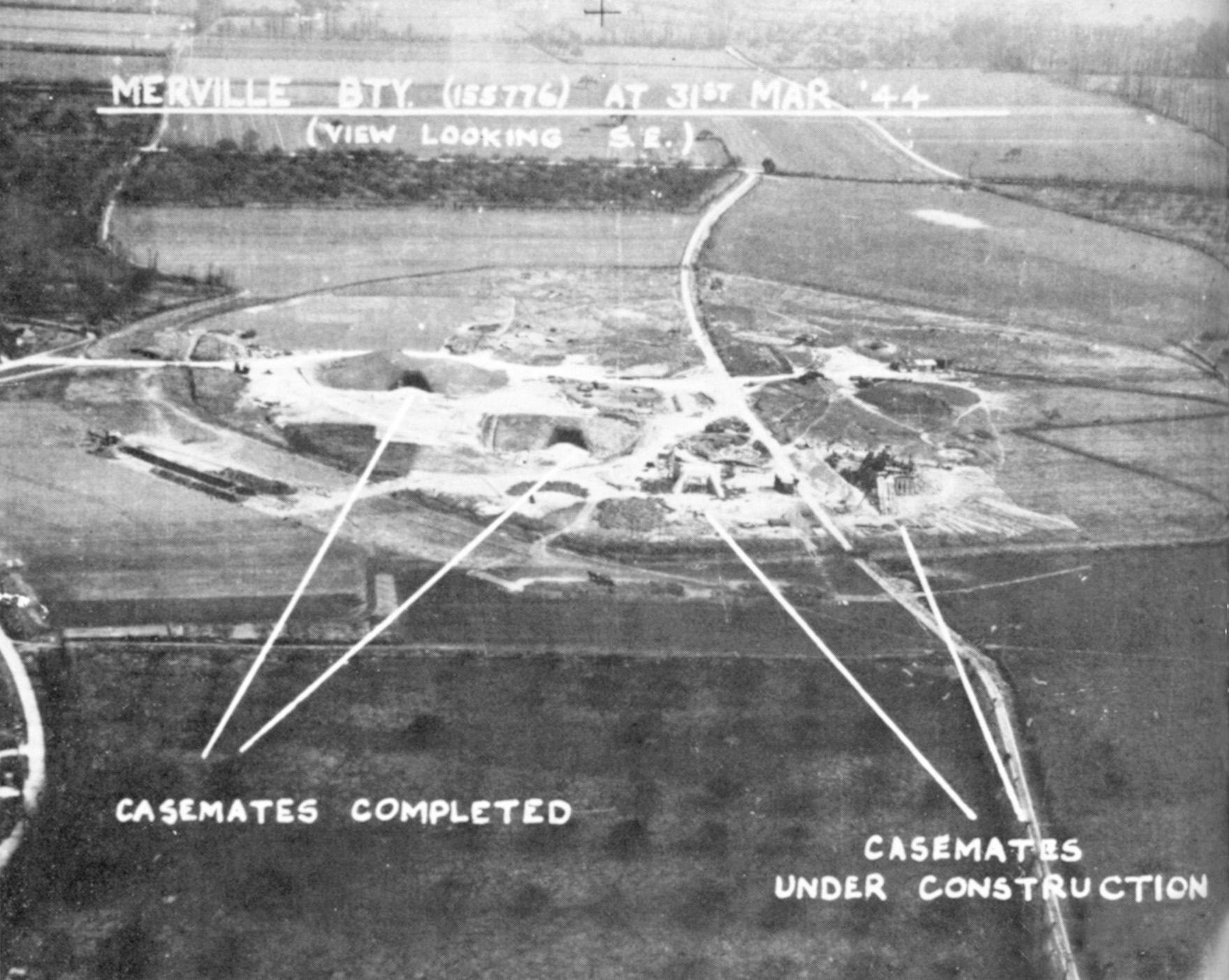

The Merville Battery enfiladed miles of Sword—the easternmost—and Juno Beaches. It was believed to contain four heavy guns, probably 155mm. A member of the French Resistance had once seen the barrels and stuck his hand in one; comparing the width of his hand to the size of the tube, he estimated its diameter at 100mm or more. The guns were hidden in thick concrete casemates, and the whole position was heavily fortified. Its western and northwestern sides were covered by a formidable antitank ditch, 10 feet deep and 14 feet wide. The entire battery was hedged in by barbed wire as well, two belts of it. If the outer belt was not much of an obstacle—one description called it a cattle fence—the inner one certainly was: 6 feet tall and about 10 deep. Between the two belts of wire the Germans had laid a minefield and had scattered mines elsewhere around their perimeter.

“A Grade-A Stinker of a Job”

Intelligence estimated the German garrison at 160 men who would fight from some 15 prepared positions with infantry small arms and machine guns. Aerial photos also showed three positions for 20mm antiaircraft guns, which could be used against personnel on the ground as well. At least one such gun was already in position. Any attack on the battery would have to strike in the darkness before dawn, and it would have to neutralize the guns before daylight came.

The task fell to the 9th Battalion, 3rd Brigade of the Parachute Regiment, originally recruited largely from volunteers of the 10th Battalion, the Essex Regiment. The brigade commander was Brigadier James “Speedy” Hill, who had earned his nickname from his obsession with physical fitness and forced marches. Hill chose his 9th Battalion commander carefully, newly promoted Terence Otway. He had a special job for the battalion, the brigadier told Otway. It would be, he said, “a Grade A stinker of a job.” He did not exaggerate at all.

Otway was a 1933 Sandhurst graduate and the son of a military family. Commissioned into the Royal Ulster Rifles, he saw active service and combat in Shanghai and on the Northwest Frontier of India. He was a serious soldier—tough, uncompromising, demanding of himself and others—and very much a student of his profession. “My job,” he said of himself, “is to ensure that the life of one soldier under my command is never prejudiced by my own military inefficiency.” He was the kind of officer soldiers liked to go to war with.

Otway first saw his target in England, at a heavily guarded farmhouse at Netheravon. Inside the building one room held a large-scale model of the Merville battery, and the walls of the room were plastered with maps and aerial photographs. He was to spend many hours in that room, poring over the model and the maps, painstakingly studying both the target and the heavily hedged bocage country of Normandy around it.

As Otway’s battalion liaison officer, Captain Robert Gordon-Brown, pithily put it, there was “no bloody sense in having to fly over the Atlantic Wall and then stick our bums right in front of a heavily defended gun battery wherever it might be.” So one of Otway’s early decisions was to land well behind the battery, organize, then take it from the rear. He had seen in the aerial photographs that there were no tracks or paths behind the battery casemates; its guns were trained on the beaches, then, and could not be pulled out and turned inland.

Gordon-Brown helped his boss all he could, as did an assortment of first-class staff officers. He was carefully cared for by his batman-driver-bodyguard, Corporal Joe Wilson, ex-boxer and gentleman’s gentleman, who plied his preoccupied boss with tea, saw to it that he ate more or less regularly, and tried to make him rest, at least occasionally. But Otway was immersed in the problem of the battery, well aware of its critical importance to the whole of the invasion of Fortress Europe. He could not fail to take it out. And so, at length, he arrived at his plan, complex but workable.

The battalion would parachute into a drop zone (DZ) about a mile and a quarter east of the objective. Pathfinders of 22nd Independent Parachute Company would drop in first to mark the DZ for the main drop. The pathfinders would also set up Eureka homing beacons to guide the main body of troop carriers in on the DZ. Company C of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion would go in with them to secure the ground.

Meanwhile, about a hundred Avro Lancaster heavy bombers were to strike the battery. Although previous strikes had scored direct hits on casemates and failed to destroy them, this raid might damage the softer defenses and would at least keep the defenders occupied. The battalion’s path to the objective would be screened by A Company of the Canadians. If the assault failed for any reason, the cruiser HMS Arethusa would begin to shell the battery at 0530. Arethusa’s guns were to be controlled by a naval party that would parachute in with Otway’s men, and the cruiser would be available to shoot in support of the battalion as well.

Brigadier Hill had driven the brigade, including 9th Battalion, through a murderous regimen of physical training. Many of its men had begun their training in the heart of winter, running in the snow in shorts and singlets. All ranks ran everywhere, climbed cliffs, ran assault courses again and again, ran long distances carrying full packs. Brigadier Hill led them personally on 50-mile marches: 25 miles out, a two-hour rest, then 25 miles back. Afterward, some soldiers had to cut off their socks, which were stuck to their feet with blood, but the battalion quickly grew very hard, hard enough to pass Speedy Hill’s standard for physical competence: 112 miles in 21/2 days carrying 60-pound packs.

Parachute training began with two jumps from a tethered balloon and ended with six jumps from an aircraft. In addition, they spent many hours on the range, and some were training to use German infantry weapons as well. Units operated at night for one- to two-week periods, getting used to fighting and moving cross-country in the dark.

Otway was a careful leader who left nothing to chance. Back in England, at Inkpen in Berkshire, he had put his battalion through several rehearsal attacks on a full-sized mockup of the battery. That mockup in itself had been a minor miracle. It was built near the town of Newbury and was correct right down to the Achtung—Minen! signs on the dummy minefields. Bulldozers reproduced the antitank ditch, engineers built casemates out of cloth and tube steel; even the roads and tracks surrounding the battery were reproduced precisely. The whole magic operation had taken just a week, and Otway could put his men to rehearsing.

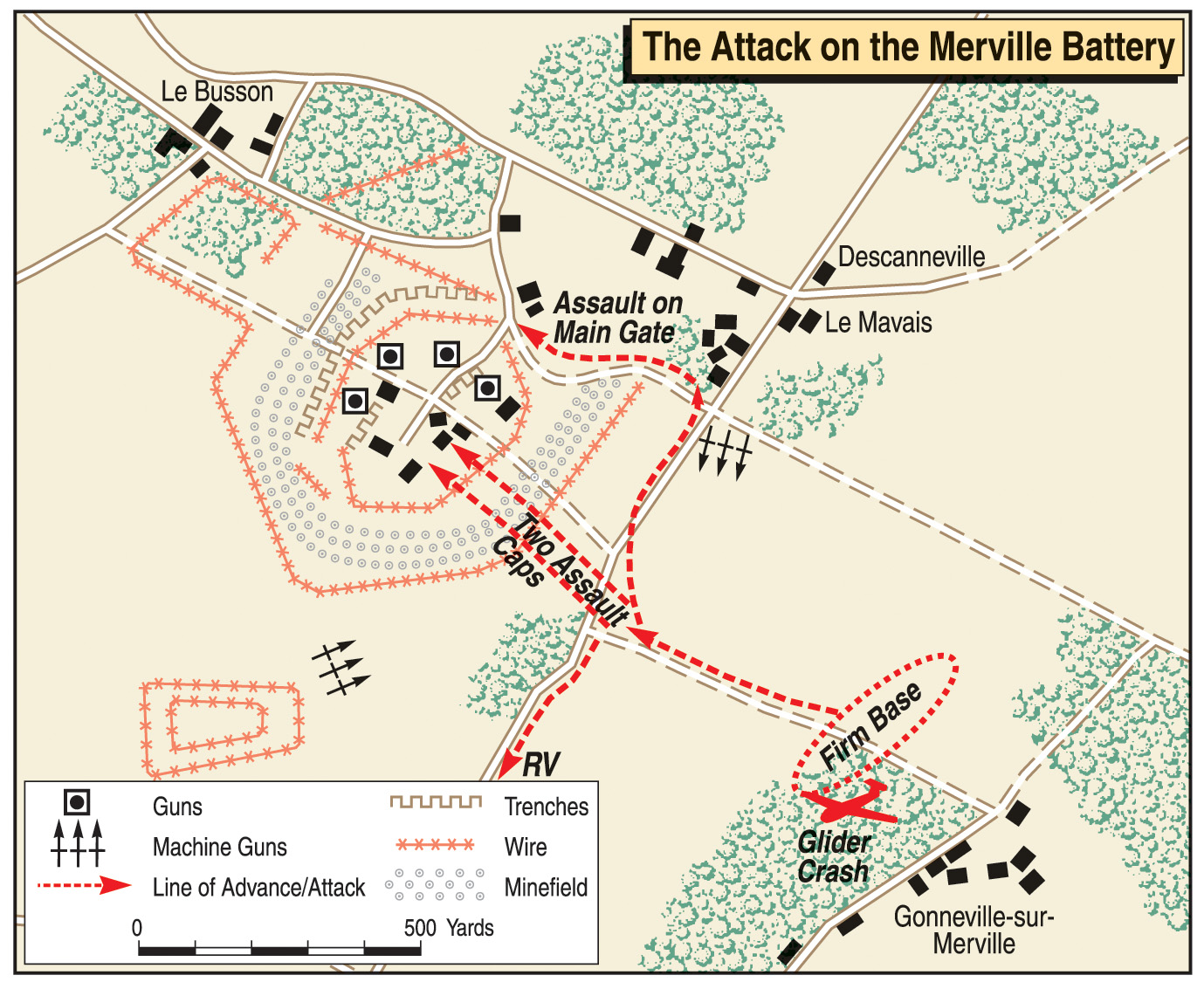

Otway had laid on what the British called a rendezvous (RV) party, which would jump in at 12:20 am to control assembly of the battalion on the DZ. At the same time the British would insert a “Trowbridge Party” (named for one of Lord Nelson’s captains, who watched the French fleet before Trafalgar). This reconnaissance element was composed of just three men: Major George Smith, Company Sgt.-Maj. Dusty Miller, and C.S.M. Bill Harold. They would move immediately to the battery and observe, reporting by radio to Otway back on the DZ. Still another special party would clear gaps in the minefield and mark the best approach to the battery with tape, as the Trowbridge Party directed.

Gliders, Torpedoes, and Flamethrowers

Five gliders would carry in the heavy gear: jeeps, 6–pounder antitank guns, flamethrowers, scaling ladders to help in crossing the antitank ditch, and an assortment of explosives. The main body of the battalion would jump at 12:50, organize, and move out for the objective at 2:35. At about 4:10 they would form up roughly 500 yards from the objective. Then, some 20 minutes later, three Horsa gliders would land inside the battery perimeter, carrying paras of A Company and sappers of 591 Parachute Squadron. These men—70 of them—would carry rings of explosives, like cheeses, to clamp around the barrels of the German cannon. As the gliders ran in to land, a bugler would blow reveille, and Otway’s mortars would illuminate the battery with flares.

Two and a half minutes later, when the bugle sounded fall in, all fire would stop, and the gliders would crash-land inside the wire, putting down between the casemates, which would tear their wings off and bring them to a halt on top of the objective. As they did, Otway’s bugler would sound lights out, the flares would cease, and the infantry would go in in the dark.

B Company was to blow the gaps in the inside belt of wire with bangalore torpedoes, 6-foot metal tubes two inches thick, loaded with explosives. Any number of bangalores could be screwed together and pushed under a wire entanglement or into any other obstacle, then detonated. A Company would then assault through the gaps. As they did so, the glider parties would attack the casemates with flamethrowers, grenades, and small arms.

Using live ammunition, 9th Battalion practiced its assault over and over, by day and by night, minus the gliders, which could not be spared for rehearsals. Every para knew his mission by heart, and Otway made sure it was imbedded in memory by requiring every man to make a sketch at the end of the exercise, detailing his part in it. They were as ready as men could be, making last-minute adjustments to their gear, choosing what weaponry they would carry. That choice was largely a matter of individual taste. Some men modified their Sten guns by stripping off the stock; others traded small-arms ammunition for more grenades.

On the morning of June 4, battalion chaplain John Gwinnett held a service, and the theme he chose struck precisely the right note. “Fear knocked at the door,” he preached. “Faith opened it, and there was nothing there.” At the same service, he blessed a flag depicting Pegasus, the winged horse that was the Airborne symbol, made for the battalion by Women’s Voluntary Services of Oxford. The men liked Gwinnett. As much a paratrooper as they were, he would jump into the dark night of Normandy with them. The flag would go, too.

Brigadier Hill spoke to the men of the battalion, as did Maj. Gen. “Windy” Gale, the towering, tough commander of the 6th Airborne Division. “The Hun thinks only a bloody fool will go there,” General Gale told his men. “That’s why we’re going.” The paras cheered him. And Otway spoke to his lads too; his were quieter words, a few sentences of confidence addressed personally to each of his soldiers, one at a time.

These men were trained to a gnat’s eyelash, all of them, from general to private. They were eager to get on with the mission, and Gale’s blunt statement was the sort of talk they wanted to hear. They had confidence in their leaders, who would land with them to face whatever they would face, the division commander included. Speedy Hill would go in with the lead aircraft of his brigade, first kicking out into the darkness a soccer ball with Hitler’s face painted on it.

And so, as all the world now knows, the greatest invasion armada in history set out from every port in England, headed for Festung Europa. Thousands of aircraft rose into the darkness from dozens of airstrips, and three divisions of paratroops boarded cargo aircraft, loaded down with gear for their jump into the flak-filled darkness over Normandy.

It would take some 400 transport aircraft to lift the British 6th Airborne Division alone. Some of the British troopers were unlucky enough to have to jump from Albemarle bombers, converted for Airborne operations by cutting a hole in the floor. The men, loaded with weapons, harness, parachutes, and kitbags full of gear, could not stand up inside the bomber’s fuselage. They had to crawl everywhere inside the aircraft and try to cram their bodies, bulging with gear, through the hole when time came to jump. The Albemarle was cordially detested by the troops, but there were not enough of the faithful C-47 Dakotas to go around. Whatever they rode into battle, the paras were cheered by ground personnel as their loaded aircraft rumbled down the strips and into the darkness. The jump was on.

In France, anxious members of the resistance were glued to their clandestine radio sets, listening with delight to the messages they had waited for for so long. A series of meaningless phrases gave specific directions to various resistance groups. And then it came. “The children get bored on Sunday,” said the quiet BBC voice, and the listeners sprang into action. It was time.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, overall Allied commander, had made his heart-wrenching decision to commit the invasion forces in very marginal weather. That weather, plus German flak that caused many troop-carrying aircraft to take evasive action, resulted in a scattering of Allied paratroops over miles of interior Normandy. Streams of red and yellow German tracers looped up through the gloom, reaching out for the hundreds of transports hammering in low over Norman villages and farmland. Many of the aircraft jinked violently to avoid the flak, throwing heavily loaded paratroopers against the sides of the fuselage and onto the metal floor.

Visibility for the pilots was very poor, there was no signal from the Eureka beacons, and many aircrew overshot their DZs in the darkness and dust. These aircraft promptly turned to come around again, until the air over the DZs was a milling mass of aircraft and parachutes. Some pilots made half a dozen runs before they could get all of their eager paras out the door.

“Do Not Be Daunted if Chaos Reigns. It Undoubtedly Will.”

Like their American counterparts farther west, the British were dropped everywhere over miles of dark countryside. American troopers, groping in the gloom, recognized each other by clicking little metal crickets, of the sort children played with on Halloween. Speedy Hill’s officers carried little bakelite ducks; their quacking would call their men to them in the gloom. The soldiers carried little bird-call whistles to answer. If whatever you met in the darkness did not quack, click, or whistle, you shot it.

Conditions on the ground were chaotic, but war is the province of chaos. Brigadier Hill had warned his men that it might be so: “Gentlemen, in spite of your excellent training and orders, do not be daunted if chaos reigns. It undoubtedly will.”

Otway’s Canadians were spread out for miles, and only 30 of them actually landed on the DZ. The pathfinders landed well on target but discovered that all but two of their Eurekas had been broken in landing. The Trowbridge Party also hit the DZ and immediately headed for the target area. They were forced to wade broad, water-filled ditches bordering each field, ditches unmarked on their maps, and it now also appeared that the Germans had opened the River Dives sluices and flooded the fields, four feet deep, for miles east of the DZ.

Shortly after the first small parties were on the ground, the paras heard the thunder of the heavy-bomber force, which managed to miss the battery and scatter bombs across the drop zone and through the fields around it. Although nobody was hurt, the impact of the bombs raised an enormous cloud of dust, which was still hovering above the DZ when Otway’s main force approached at 12:45. Major Alan Parry, commanding the RV party, tucked his red Aldis lamp into a tree as a guide, but the 32 Dakota transports were already scattered and many were off course.

Between the dust, the darkness, heavy flak, some patchy cloud cover at about a thousand feet, and a strong easterly wind, Otway’s paratroops were widely scattered. Some landed in the flooded fields to the east, and a few of these, loaded with gear, drowned in the water-covered mire. Some were bounced out of the open door of the aircraft as they awaited the signal to go and landed miles from their objective. One stick came down 30 miles away. The men who had jumped came out into winds of up to 20 miles per hour, above the level considered safe even by day.

But these were tough men, determined to come to grips with the enemy. They had not trained so hard for so many months to miss the action. Private Tony Mead, for example, went out into the night behind his officer, Lieutenant Jimmy Loring. Mead was carrying spare radio batteries and Loring had a carrier pigeon tucked inside his jacket—the distinctive “smock” of the Airborne. The pigeon was scheduled to depart for England with the good news that the battery was captured … when and as that happened in this chaotic darkness.

Mead landed in the treetops and was impaled by a sharp branch that stabbed up into his abdomen. He got himself unstuck from the branch and dropped 15 or 20 feet to the ground. With blood running down his leg and pooling in his boot, he jammed one hand over the wound, grabbed his Sten gun with the other hand, and staggered off to find his company. He was not, he told an NCO, going to get left out of the war after he had come this far.

On another aircraft that had already made two runs through flak to drop its human load, the pilot made the decision to return to England. A para sergeant, still waiting with another man to jump, collared the RAF jumpmaster. There would bloody well be another run, he said, or “he and his mate would jump out and effing well take him with them, parachute or not.” The pilot, listening to all this on the intercom, turned back into the maelstrom of fire and crossed the DZ for the third time. The sergeant and his mate got their jump.

Otway’s experience was typical. His Dakota, the lead aircraft, also carried the taping party and the tape. As the pilot tried to avoid German flak the aircraft bounced violently, throwing many of the troops onto the floor in a tangled heap. It took three runs to empty the aircraft, and its passengers were scattered anywhere but the DZ. Otway, swinging beneath his chute and peering down into the gloom, saw that he and another para were landing next to a building used as a German headquarters.

As the occupants of the building opened up on them with pistols, the para’s hand fell upon a brick, which he hurled through the window. Apparently thinking the missile was a grenade, the pistol-shooters hit the floor long enough for Otway and his companion to get out of the line of fire. Otway’s batman made a singularly ugly landing, crashing through the glass of a greenhouse on the same property, but he would find his boss on the DZ.

Otway took over an hour in getting to the DZ, and found himself almost alone once he got there. His taping party managed to extricate itself from flooded fields and join him, but the tape was lost. Then, a few at a time, scattered paratroops began joining him, but many of their comrades were miles away in the darkness, and most of them would not find the DZ in time to move off toward the objective. Around them the night was hideous with the cries of cattle, wounded or dying from the misdirected bombs of the Lancasters.

There was more bad news. The gliders carrying the heavy weapons, fighting heavy winds and unable to see the DZ through the dust, smoke, and darkness, were down miles away, some smashing into antiglider poles, killing and wounding some of their passengers. Five other gliders, loaded with more equipment and supplies, had broken their tow-ropes in a storm over the Channel and disappeared forever. Near the DZ the paras had been able to find a few weapons containers, equipped with small lights to guide the men to their location. But that was all.

Chaos and Brandy

Otway’s report on that night’s action puts the position succinctly: “By 0250 hours the battalion had grown to 150 strong with 20 lengths of bangalore torpedo. Each company was approximately 30 strong. Enough signals to carry on—no 3 in mortars—one machine gun—one half of one sniping party—no six pounder guns—no jeeps or trailers or any glider stores—no sappers—no field ambulance, but six unit medical orderlies—no mine detectors—one company commander missing.”

Brigadier Hill’s “chaos” had come to pass.

Otway waited as long as he could on the DZ. And then, about 10 minutes to 3, he started for his objective with what men he had. Of a battalion of about 540 paratroops, he still had collected only some 150. They would have to do. Corporal Wilson, Otway’s imperturbable batman, chose this moment to gently ask his officer, “Should we have our brandy now, sir?” Otway drank it off and led his men into the night.

They stealthily skirted farms and bypassed the village of Gonneville-sur-Merville. Under a pale moonlight, the dark fields were studded with huge bomb craters, littered with dead and dying cows. Once the little column had to dodge a minor stampede of frightened cattle, and once the remnants of A Company, leading, froze behind a hedge while a German patrol passed. The unsuspecting Germans were cold meat, but the paras’ orders were to reach their objective undiscovered. Nobody fired.

Along the way to the battery, Otway met Major George Smith, commanding the Trowbridge Party. Smith had been busy: He and his sergeants had cut through the outer ring of wire and cleared four paths through the minefield by feeling for tripwires with their hands in the darkness. Having no tape, the marking party had marked a path by dragging their boots through the earth. Smith had spent some time lying in the night outside the inner belt of wire, listening to the Germans talking and laughing inside the position. The enemy was alert, he reported, but not alarmed.

Forced to attack with many fewer men than the original plan called for, Otway now changed his approach. He would blow two gaps in the inner wire. A party would run into each gap and throw their bodies onto the edges of the wire. Right behind them, running hard, would come two attack teams, one through each gap. These would again split into two sub-teams each, one for each of the artillery casemates. Still another group of paras would take on the German machine guns scattered around the position, and a diversion team would strike the main gate of the position. Speed and violence would have to make up for missing numbers and firepower.

The three gliders that were scheduled to land inside the position itself would have to go in in pitch blackness; there was no mortar to fire illumination rounds according to plan. And in any case the gliders were having trouble of their own. One had turned back, its tow-rope broken. A second, damaged when its arrestor parachute deployed by accident and tore into the glider’s tail, missed the battery in the gloom and splashed down in a watery field to the east.

The third glider, also unable to see its target, banged into an orchard about 50 yards from its objective. Its paras would not get to the battery either, for as they climbed out of the glider they heard Germans approaching, dropped into the nearby ditches, and opened up. A close-range firefight ensued, and this glider’s paras would not be able to break contact and get to the objective. Neither, however, would the Germans, men of the 736th Infantry Regiment, be able to help their comrades at the battery.

At about 4:15, a half-hour before dawn, Otway launched his attack. “Everybody in!” he roared. “We’re going to take this bloody battery!” The bangalore torpedoes exploded with a roar, and with Otway and his men shouting “Get in! Get in!” 9th Battalion got to its collective feet and charged. One of Otway’s officers—Lieutenant “Twinkletoes” Jefferson, a former ballet dancer—sounded a hunting horn. The diversion party, six men and a sergeant, rushed the main gate. Otway’s two assault parties blew holes in the inner wire, and the infantry went in at the double, everybody yelling and shooting from the hip.

The startled Germans opened up a lethal cross-fire with approximately 10 machine guns. But return fire came from the lonely Vickers machine gun of Sergeant McKeever, a legendary MG wizard. McKeever again worked his magic and quickly took out three of the defenders’ weapons. The diversionary party accounted for three more with fire from a Bren gun and their rifles. Some of Otway’s paras went down under a hail of German bullets. Others stepped on mines in the gloom. Lieutenant Jefferson, the ballet dancer, would not dance again. The adjutant, Captain Hal Hudson, took a bullet in the belly; a slug tore through Otway’s water bottle and another through the cloth of his smock.

But there was no stopping the paras’ hell-for-leather charge. Once through the wire, they tossed grenades into casemate embrasures and entries, then lunged inside to finish the job with Sten guns and bayonets. Private Tony Mead, still holding in his guts, was in the thick of the fight, pouring bullets from his Sten into the firing port of a German pillbox.

The fighting went on, hand-to-hand in the gloom of casemates and underground passages, until, about 20 minutes later, the handful of German survivors threw up their hands and gave it up. The story goes that they quit when one of them saw wings on a soldier’s jump smock and screamed “fallschirmjaeger!”—paratroops! German troops had a healthy respect for the paras; indeed, one German officer later grumbled that it “was unfair for troops of the sort found in the German 346th Infantry Division to be sent into action against British Airborne troops.”

The Merville guns turned out to be old French 75mm guns, deadly enough, even if they were not the heavier weapons intelligence had expected; those had not yet been installed. Without their cheese-shaped explosives, the paras had to improvise a way to destroy the guns. They used Gammon bombs, plastic explosive with a detonator stuffed into an elastic bag rather like a sock.

The paras had taken more than 20 prisoners, and the casemates and the ground inside the wire were littered with dead and wounded Germans. Others were dead in the tunnels. Of Otway’s paras, only about 80 men were still in condition to fight. These got the wounded out of the battery perimeter, now under German artillery fire, to a Calvary cross standing some 700 yards south on the Breville road.

Four British officers were wounded, one dead; some 65 other ranks had been killed or wounded. About 30 casualties were being treated at the battalion aid station, set up in a barn. Twenty of these were stretcher cases, and tough Tony Mead was one of them, shot while inside the battery. His exertion in the attack had also forced a piece of intestine through the tear in his side. Doctor Bobbie Marquis, a para lieutenant, operated with a razor blade and saved Mead’s life.

Chaplain John Gwinnett had spent the early morning collecting stragglers and leading them to the temporary brigade headquarters at a town called Le Mesnil. Hearing that the paras’ seriously wounded had been gathered into a derelict barn near the battery, he liberated a German truck, drove across country in the dark, and made several trips to move the worst of the wounded to the brigade aid station.

Battalion Adjutant Captain Hal Hudson, desperately wounded, made it to the improvised dressing station thanks to the padre’s initiative and courage, with an assist from Major Alan Parry, A Company commander, crippled by a leg wound. Deep in the Valley of the Shadow, almost at the coma stage, Hudson reached out for some sort of contact. In Hudson’s time of need, Parry gripped and held his hand on the way to the farmhouse kitchen table that the brigade surgeons used as an operating table. Determined to live, Hudson kept his mind focused on the men he admired most, Brigadier Hill and division commander “Windy” Gale. Hudson would survive to become Sir Havelock Hudson, chairman of Lloyds of London.

Jimmy Loring, the signals officer, now fished the somewhat-bedraggled pigeon out of his smock and sent it on its way. Sergeant-Major Miller thought the bird “looked a ruffled old specimen,” but the pigeon took a businesslike circle around the battery and promptly set off for England. The bird arrived safely, and its jubilant message made the evening news on the BBC. Loring also took care of the worrisome matter of HMS Arethusa, firing a yellow Very-pistol flare to call off the bombardment of the battery, scheduled for a rapidly approaching 0550. The flare was not the green-red mortar flare the ship was expecting, but Arethusa understood. The only shells landing in the battery area were German.

Memories of Heroes and Battles

One story tells that later in the day the Germans may have reoccupied the battery area until they were overrun and killed by men of Number 3 Commando. Some on the Allied side believed the guns had actually opened fire on the landing beaches at that time, but Lieutenant Raimund Steiner, commanding the battery, later said flatly that no such thing occurred. And after the destruction wreaked by the Gammon bombs, it is most unlikely that any of the Merville cannon ever fired a round in anger.

Once the battery was secure and its wounded cared for, the battalion moved on toward its next objective. Hill’s Brigade was now to hold a critical ridge cutting across the east-west lines of communications and dominating the line of the Dives Valley. The 9th Battalion, collecting stragglers as it went, moved to do its part in holding that line against the inevitable German counterattacks. That later fighting—six days and nights of it—was protracted and vicious. At one point so many German dead were stacked up in front of McKeever’s Vickers gun that the crew could not see over the corpses.

The Merville battery is placid and peaceful today, a grassy, pleasant place much visited by tourists. The trees cut down by the Germans to provide an all-around field of fire have been replaced. The village of Merville has erected there a bust of Otway, placed on a stone pillar, and a little museum displays memorabilia of his gallant battalion.

Only the memories remain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments