By David A. Norris

On April 5, 1862, the Fourth Corps under Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes pushed forward along the road by the James River. They trudged and splashed through soggy Virginia woodlands, relieved with occasional openings for farmlands and fields. Confederate resistance was light, nothing compared to the impediments of mud and water. Still, Keyes expected to easily follow the roads to Halfway House. Then, according to the Union plans, his corps would hover by the right flank of the outnumbered Confederate force of Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder in Yorktown. Before long, the dreams of an easy victory dissipated. Cutting across Keyes’ intended route was the Warwick River, a wide stream expected to be some distance to the west instead of blocking his march. Beyond the water, on the opposite shore, Confederate muskets and cannon opened fire. The swift advance of a few hours envisioned by Keyes’ superior, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was about to turn into a month-long siege that provided a grim foretaste of the slow progress and ultimate failure of the Union’s Virginia Peninsula Campaign.

The winter of 1861-1862 was a time of bleak uncertainty for the Union cause. The previous summer, amid a surge of confidence, a Union army under Brig. Gen. Irwin McDowell drove directly against the forces of the newly formed Confederate States. But instead of pushing “on to Richmond,” McDowell’s army was wrecked and plunged into a headlong retreat at the First Battle of Bull Run or Manassas on July 21, 1861.

As thousands of soldiers shielding the Federal capital of Washington and the Confederate capital of Richmond, only 90 miles apart, the war settled into an uneasy stalemate, punctuated by sharp skirmishes and small battles.

On October 21, a smaller-scale clash at Ball’s Bluff on the Virginia bank of the Potomac ended in another disastrous Union defeat. There had been little good news for President Abraham Lincoln’s administration on the northern Virginia front, except for a key victory provided by McClellan.

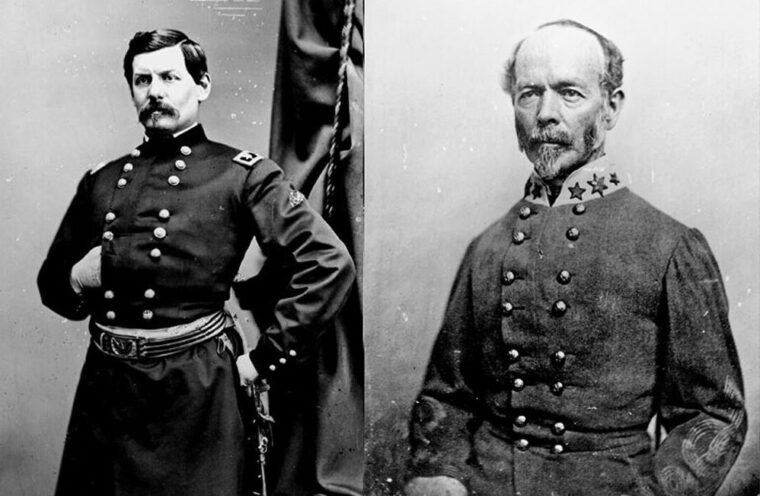

Second in the West Point Class of 1846, McClellan had served with distinction as an engineer officer in the Mexican War. While an instructor at West Point, he translated a French manual on bayonet exercises. Later, he joined a committee of officers to observe the Crimean War and the armies of Europe. His “McClellan saddle,” an adaptation of a Hungarian military saddle, was used by the U.S. Cavalry for decades.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, McClellan left the presidency of the Ohio & Mississippi Railroad to accept command of the volunteer troops of Ohio. On May 13, 1861, McClellan’s expertise in military science; his perceived efficiency and overall competence, and his charismatic and confident personality earned him a commission from Lincoln as a major general in the regular army.

McClellan was in command of Kentucky and western Virginia, areas of considerable peril if the Union lost control of them to the secessionists. He won the Battle of Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861. By later standards of the Civil War it was a minor clash, but at the time it cemented Union control of the western part of Virginia, which later broke away from the Confederacy to form the new state of West Virginia in 1863.

McClellan’s victory at Rich Mountain provided a sharp contrast to the disaster that befell the Union Army at Manassas 10 days later. Lincoln placed McClellan in command of the Army of the Potomac on July 26.

McClellan found a battered and dispirited army in a beleaguered capital city. Politicians and the press were gripped by anxiety and near-panic. Military discipline was at a low ebb, and soldiers left their camps and barracks to wander around town as they pleased.

It took only a few days for McClellan to change everything. A provost guard drawn from regular troops patrolled the streets and the saloons. Regimental officers were back in firm control—soldiers could not leave camp without permission. Newly arrived units began organized training. Plans for a spectacular circle of defenses around the capital quickly became a reality of forts, batteries, and earthworks.

The transformation of Washington from chaos to steady calm and determination was widely visible to the nation. The 35-year-old McClellan, a retired captain at the start of the war, symbolized the much-needed success and confidence. On November 1, 1861, Lincoln rewarded him with command of the entire U.S. Army.

The Confederates’ Army of Northern Virginia, under Lt. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, made winter camp at Centreville, near the old battlefield of Manassas. In command of the Union Army, McClellan not only watched Johnston, but planned spring operations in Tennessee; on the Mississippi River; and the coast of North Carolina. Though full of ambitious plans, he made no effort to clear enemy troops from the Potomac River region.

Lincoln, anxious to clear the Rebels out of easy range of Washington, announced General Order No. 1 on January 27, 1862—commanding combined army and navy offensives against the Confederates on all fronts by February 22. A clarification was added a few days later, ordering McClellan to attack Johnston.

Nothing directly came from Lincoln’s order, though it did prod McClellan into committing to a concrete plan of action. Mindful of the failure of McDowell’s direct dash against Richmond, McClellan had for some time envisioned outflanking the Confederate forces opposing Washington via the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. In response to Lincoln’s orders, McClellan wrote a detailed letter describing a plan to land an army at Urbanna on the Rappahannock River. From there, it was 60 miles west to Richmond. McClellan thought he could be in the Confederate capital before Johnston could move from Centreville.

McClellan appeared nonchalant about Washington, feeling the Confederates could not menace the Union capital without losing their own. But the capture of the national capital was one of Lincoln’s greatest fears. Such a strategic catastrophe might cost the United States the confidence of Great Britain, France, and the other European powers. So far, European recognition of the Confederacy was no more than a daydream for Jefferson Davis’ government.

In reacting to his landing at Urbanna, McClellan felt the Confederates would have no spare troops to threaten Washington as they scrambled away from Centerville to face the large Union force bearing down in Richmond from the east, supported by Union Navy gunboats. Lincoln reluctantly consented, provided that McClellan leave enough troops to protect Washington.

But circumstances soon made the Urbanna plan unworkable. Johnston quietly began leaving his winter camp on February 23, intending to move his army to Richmond. The last Rebels left there on March 9 and Johnston concentrated his force along the Rappahannock River. McClellan left Washington with a large force to chase the Confederates, but Johnston was far ahead and the Federals found only the empty winter camps. Making matters worse, Johnston burned the bridges over rivers and streams now swollen by recent rains as he moved south.

After Johnston’s easy escape, Lincoln removed McClellan as commander in chief of the Union Army on March 11. Lincoln felt the general’s full attention should be devoted to the Army of the Potomac while it was in an active campaign. McClellan had also run afoul of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who wanted a more aggressive war against the secessionists.

Abandoning the Urbanna plan, McClellan planned a landing on the Virginia Peninsula. One of Virginia’s three major peninsulas, it stretches 50 miles between the James River on the southwest and the York River to the northeast, varying from 5 to 15 miles in width.

Steeped in history, the Virginia Peninsula was the site of Jamestown and Williamsburg, as well as the site of Lord Cornwallis’ surrender to the army of Gen. George Washington in 1781. In early 1862, it was the site of something much more valuable to the Union: Fort Monroe.

Also called Fortress Monroe, this massive work was the largest stone fort built in the United States. In 1861, secessionists quickly took control of southeastern Virginia, including the U.S. Navy base at Norfolk. Only Fort Monroe, bristling with guns at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, remained in Federal hands. This practically impregnable bastion, easily supplied by water, made a safe starting point for a Union offensive in Virginia.

From that invulnerable base, McClellan would move his army inland. The York and James Rivers were deep enough to accommodate the Union Navy. Warships bearing heavy guns could shield the advance and provide mobile artillery platforms to harass the Rebels from both flanks, while transport vessels could provide a steady stream of food, ammunition, and supplies. Backed by the agreement of his corps commanders, McClellan obtained Lincoln’s approval.

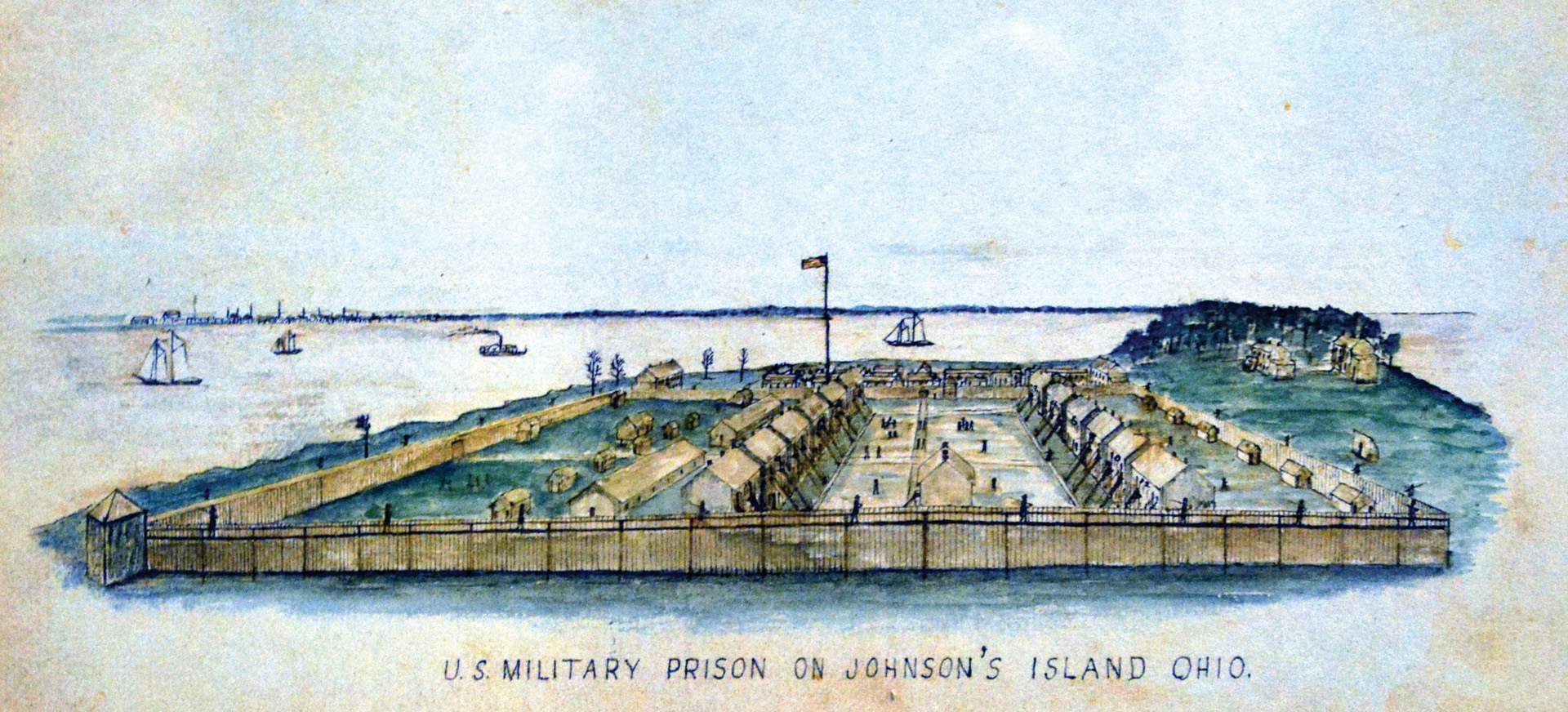

Commanding the Confederate troops on the Virginia Peninsula was Brig. Gen. John Magruder, an old-time soldier who served in the War with Mexico. With 11,000 men, Magruder anchored his line on the left at Yorktown, and from there across the peninsula to the James, built a line of earthworks, trenches, and rifle pits punctuated with redoubts and batteries. Some of his defensive line absorbed old earthworks left over from Cornwallis’ ill-fated stand at Yorktown in 1781.

Magruder did not expect to repulse the Union Army for good, but he felt that he could conduct a delaying action that would give the Confederates time to reinforce Richmond and its defenses.

When Johnston abandoned the Centreville camps, McClellan had 200,000 men around Washington and northern Virginia, almost three times the 70,000 Rebels scattered from the Shenandoah Valley and the Allegheny Mountains down through Richmond and on to Norfolk.

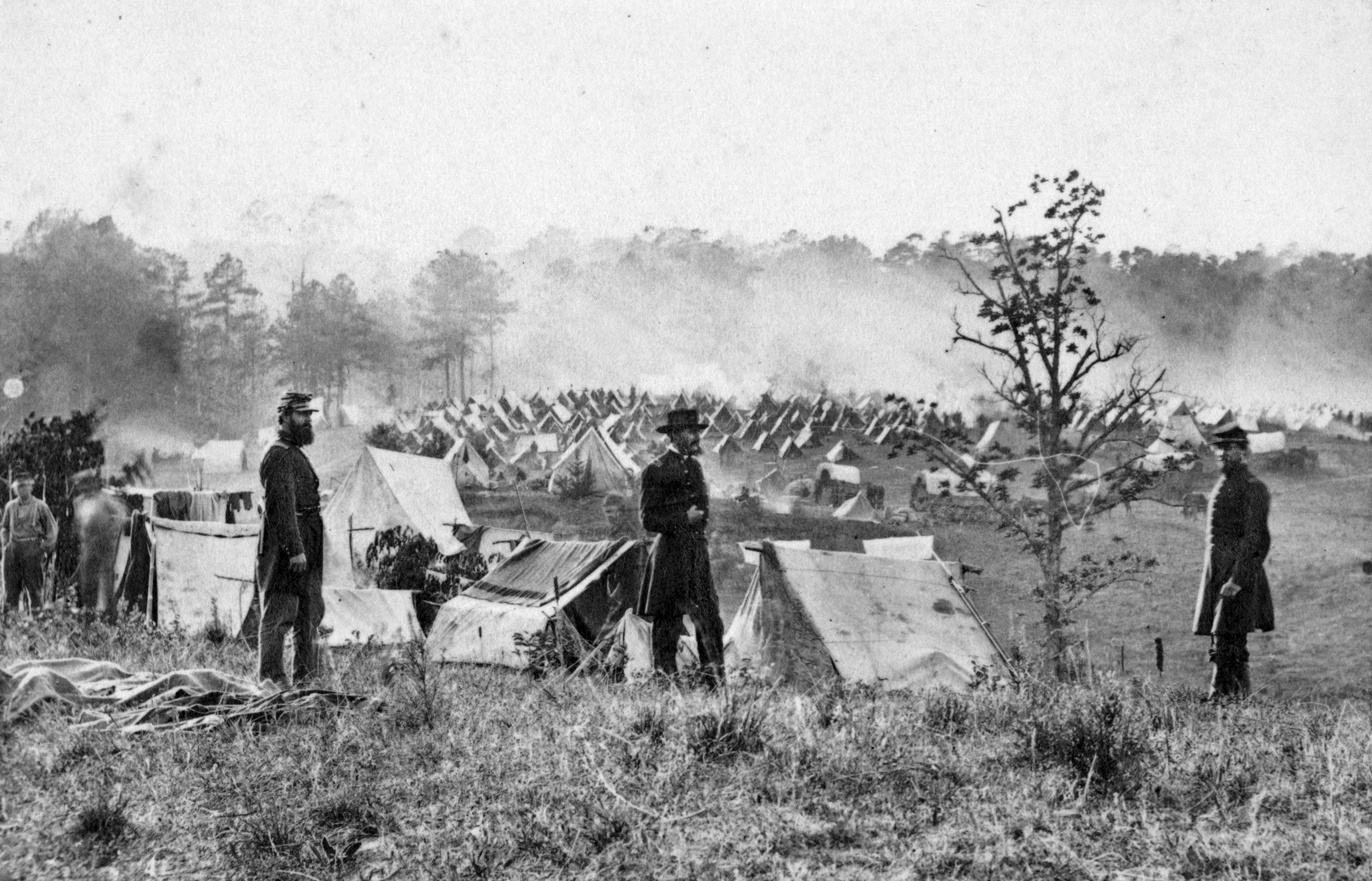

With the Union plan in motion, the first transport steamers loaded with troops and supplies left Alexandria on March 17. It would take weeks and nearly 400 steamships, sailing vessels, and barges to ferry a force intended to include 121,500 men, 14,592 draft animals, 1,150 wagons, and 44 batteries of artillery to Fort Monroe.

On April 2, McClellan arrived off Fort Monroe to take charge of his massive army, but found that bad news had not been far behind. He would not receive an expected 20,000 troops—Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker and 10,000 men were dispatched to Harper’s Ferry instead and he would not be given command of 10,000 soldiers from Fort Monroe’s garrison. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough then further dampened the commander’s spirits with the news that the Navy would not provide gunboats for him. Although the clash of the ironclads U.S.S. Monitor and C.S.S. Virginia ended in a draw on March 9, the Rebel warship was still too dangerous for Goldsborough to divert any of his vessels.

Federal control extended from the muzzles of Fort Monroe’s cannon for a short distance into the countryside. Maj. Thomas W. Hyde of the 7th Maine was on picket duty beyond Newport News in early April, when around midnight, his men fired a brisk fusillade into the darkness, believing they were under attack by the Rebels. Making his way to the front, Hyde noticed that all of the firing was coming from his men. “I went down the road,” he wrote, “and discovered an old horse and two cows killed in action. The cows were soon broiling on the fire of the picket reserve, and the regiment whose men did the killing were chaffed for many days.”

Under pressure from Lincoln, McClellan left Fortress Monroe. Not all the troops he expected had arrived, but he took 58,000 men and 100 guns with him. The III Corps under Brig. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman marched on the right, aiming toward Yorktown. Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes took the IV Corps around the left along the James River Road toward a place called Halfway House. If he reached that place, four miles northwest of Yorktown, with Heintzelman pressuring that point, they could drive away or perhaps even destroy Magruder’s force. The II Corps, under Brig. Gen. Edwin Sumner, followed Heintzelman in reserve.

The columns of foot and horse soldiers, guns, and wagons spread for several miles along the roads. A Massachusetts private serving with the Engineer Corps, Warren Lee Goss, remembered, “It was a bright day in April—a perfect Virginia day; the grass was green beneath our feet, the buds of the trees were just unrolling into leaves … The march was at first orderly, but under the unaccustomed burden of heavy equipments and knapsacks, and the warmth of the weather, the men straggled along the roads, mingling with the baggage-wagons, ambulances, and pontoon trains, in seeming confusion.”

On the following day, April 5, the bright spring weather gave way to a morning of heavy rain. Under the gloomy gray skies, wrote Goss, “the muddy roads, cut up and kneaded, as it were by the teams preceding us, left them in a state of semi-liquid filth hardly possible to describe or imagine.” When Goss’ comrades reached the site of the famous Battle of Big Bethel (June 10, 1861), “the rain was coming down in sheets.”

As the weather cleared, the temperature rose. In the afternoon, Chaplain A. M. Stewart of the 102nd Pennsylvania wrote, “the entire way was literally strewed with blankets, over-coats, and various other articles which the weary and over-laden soldiers refused longer to carry.”

McClellan’s advance units drew ever closer to Magruder’s troops. Anchored on the east along the York River by heavy fortifications at Yorktown, the line of Rebel rifle pits, earthworks, and batteries combined with the Warwick River to block the peninsula. Across the York River, Confederate batteries at Gloucester Point barred the Union Navy from interfering with the Yorktown defenses.

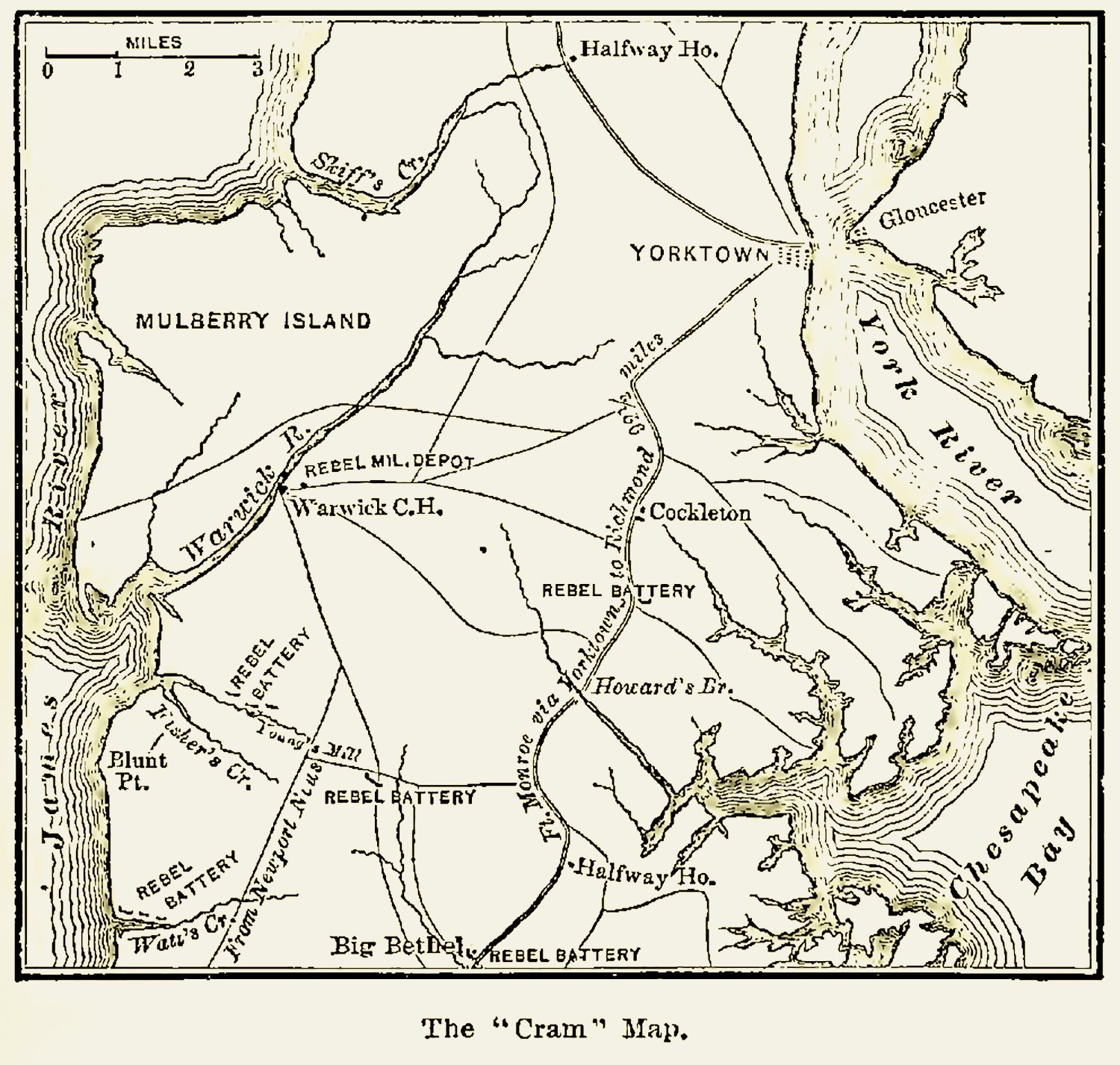

“Little Mac” had devoted only limited effort to scouting or reconnaissance work, and had plotted a route for his advance with inadequate knowledge of the terrain. Staff officers scrambled for any maps they could find, and even consulted maps of the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. The best available map appeared to be one compiled by Lt. Col. T. J. Cram, an engineer officer stationed at Fort Monroe. But Cram’s map left out many details and the further one got from Fort Monroe, the less accurate it was.

From Cram’s map, Keyes expected to march along the James River Road, past Warwick Court House. From there, it appeared that he could march east of the Warwick River and follow the roads to Halfway House. It was an unpleasant surprise to find that instead, the Warwick cut across nearly the whole peninsula blocking the line of march.

The Warwick River formed a natural defense barrier, and Magruder had taken full advantage by digging in along its northern banks. Rifle pits dotted the other side of the river where cannon faced outward from redoubts and batteries. Antebellum dams blocked the stream at Wynne’s Mill about three miles west of Yorktown, and at Lee’s Mill, another three miles downstream as the crow flies. Supplementing the deeper water in the millponds, Magruder had three more dams built—Dam No. 1 backed up water between the two mills and the other two were built downstream from Lee’s Mill. Between the dams, the low ground on the south bank of the river was now flooded. Below the dams, there were no bridges, and the Warwick was wide and deep enough to prevent an easy crossing.

Major Hyde of the 7th Maine led a 400-man skirmish line sweeping ahead of Keyes’ column. Stepping out of a stretch of woods and swamp, they were suddenly confronted by enemy horse and foot soldiers. A Confederate officer “on a white horse … immediately fired his revolver at us,” and then the enemy quickly disappeared.

Hyde’s skirmish line pressed through another stretch of woods and emerged near the banks of the Warwick River. His men halted and lay down as Rebel bullets flew past them. Then, wrote Hyde, came the order to “‘go out and draw the enemy’s fire.’ I did not like this much, but had to go, so taking a few men we crept out along the fringe of branches to the overhanging bank of the creek. I was looking to see if the stream was fordable when a crowd of men appeared on the other side looking at me and I at them, both sides rather astonished. I suddenly remembered that I ought not be there and plunged into the bushes.” The surprised Rebels came to their senses and fired at the major, but with no effect.

Hyde had been close to the enemy, “near enough to count his buttons,” as he put it. He wrote later that he was confident that the Confederate defenses were so thin at this point that he begged for permission to cross the river, but his request was denied.

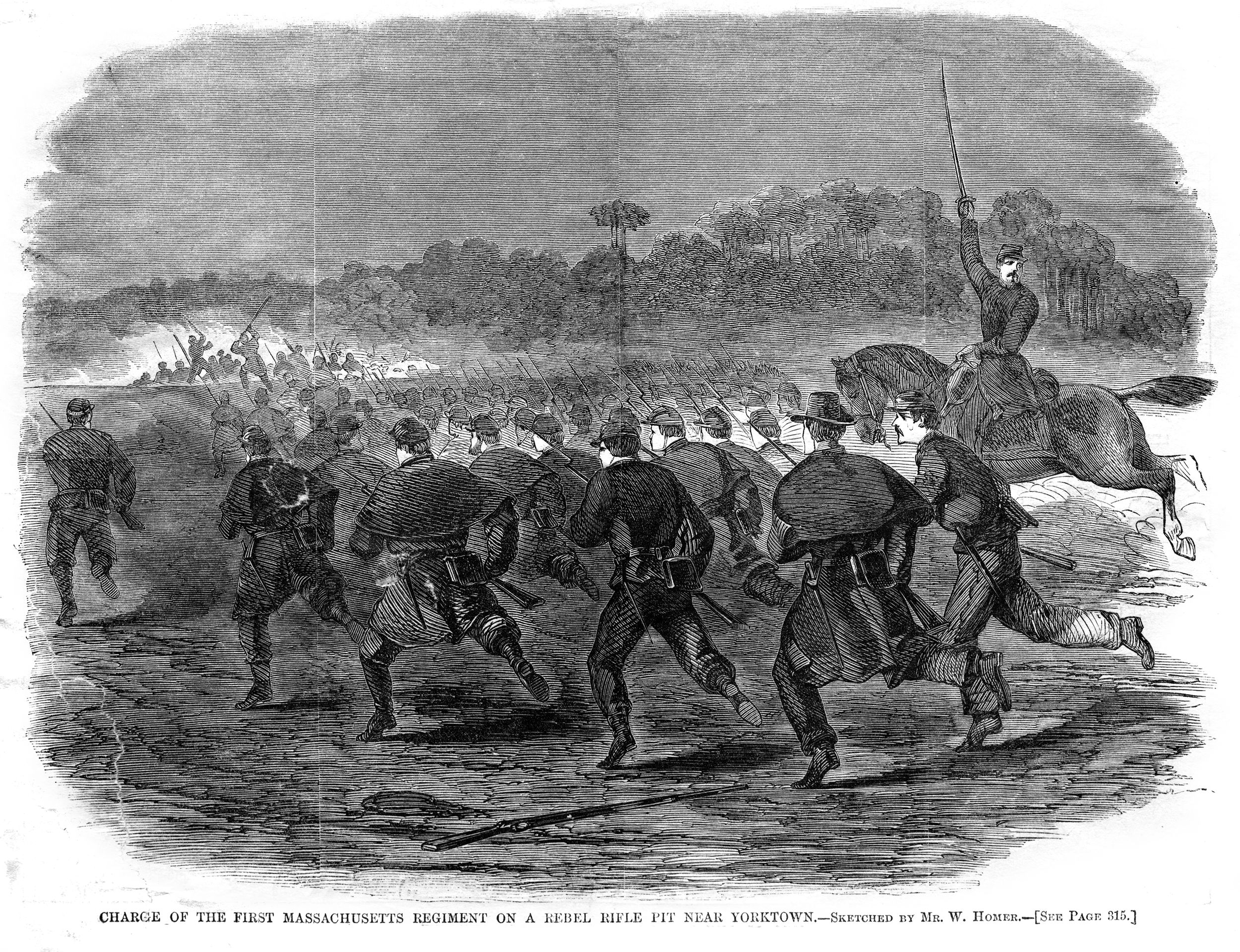

Elsewhere, more of Keyes’ troops emerged from shadowy, swampy woods to encounter musket and cannon fire from Confederate earthworks across the Warwick River. “Prince John” Magruder had over half his force in Yorktown itself or across the York River at Gloucester. This left him with only 5,000 troops spread across a dozen miles of defenses. With the skills of an actor and magician, he projected an illusion of menace and danger to the larger Union forces. Magruder’s pickets and artillery fired noisily at the enemy when they appeared. Bands of Rebel troops marched across gaps in the forests, so they could be seen. Then, they slipped back into the woods to march across the gap again to act like another batch of reinforcements. Confederate bandsmen, fifers and drummers, kept up steady background music for the deception.

Keyes wrote later of his gloomy impression of the enemy defenses. “He is in a strongly-fortified position behind Warwick River, the fords in which have been destroyed by dams, and the approaches to which are through dense forests, swamps, and marshes. No part of his line as far as discovered can be taken by assault without an enormous waste of life.” The Army of the Potomac’s chief engineer, Brig. Gen. John G. Barnard, was as pessimistic as Keyes, reporting that “those formidable works could not with any reasonable degree of certainty be carried by assault.”

In hindsight Philippe d’Orléans, the Count of Paris, a French aristocrat serving on McClellan’s staff, saw that McClellan was tricked by Magruder’s display. McClellan “did not dare to thrust his sword through the slight curtain which his able adversary had spread before his vision. A vigorous attack upon either of the dams, defended by insignificant works, would have had every chance of success. The enemy could have been kept in suspense by several feints; there were men enough to attempt three or four principal attacks at once; it was easy, in short, to harass him in such a manner that his line of defence would inevitably have been pierced at the expiration of twenty-four hours.”

After the sputtering musket and cannon fire on April 5 stalled McClellan’s advance, more bad news arrived in a telegram from the War Department. Irwin McDowell’s 38,000-man corps was to be the last contingent to sail from Alexandria. McClellan planned to send them to force the Confederates out of Gloucester, removing the protection of the Confederate batteries covering Magruder’s left. But, Lincoln decided to keep McDowell close by to defend the capital city.

Heavy rains fell April 6-10 and the Union Army was bogged down in mud. To Chaplain Stewart, “Officers, privates, horses, mules wore somewhat the appearance of drowned rats.” Soldiers worked, up to their knees in the muck, chopping trees to build corduroy roads. François d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville, another French aristocrat serving on McClellan’s staff, wrote that to get some sleep, soldiers “had to sit down on the trunks of felled trees, or to construct with logs a sort of platform, on which they snatched a very precarious rest.” Even the general of a Union division had only a bedstead made of “five or six pine branches, one end stuck in the mud, or rather in the water, the other resting on a tree. Here he slept with an Indian-rubber cloak over his head.”

Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard’s brigade, sent by steamer from Alexandria, arrived at Fortress Monroe at 7:30 a.m. on April 5. Howard was ordered to proceed immediately to Ship Point, where Cheeseman’s (Chisman’s) Creek emptied into the Pocosin River three miles south of Yorktown. With the help of Howard’s men, the Union Army built a wharf from planks salvaged from Confederate gun platforms and barges, and repaired the road from Ship Point to the main Yorktown Road. By April 6, the new landing was ready, speeding the delivery of supplies by bypassing several miles of road.

As the rain and drizzle continued for most of the next several days, Union teamsters tried to get wagons and guns to the front, their efforts punctuated by occasional skirmishes and cannon fire. A bit of good news came to McClellan on April 11, when Lincoln agreed to send him Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin’s division.

On April 16, McClellan ordered a demonstration against the Confederate forces guarding Dam No. 1 between the two mills. Three charred chimneys, all that remained of the house on the Garrow Farm burned by Magruder’s men, stood nearby as a grim landmark. Some accounts refer to this action as the Battle of the Burnt Chimneys. The attack, by Brig. Gen. W.F. Smith’s division, was intended to disrupt the Rebels’ steady construction work in the area.

Captain Thaddeus P. Mott and the Third Battery New York Artillery opened fire 1,100 yards from the Rebel works. A Confederate shell killed three of Mott’s men and wounded several others, but Mott’s fire eventually silenced the Rebel guns.

Some 200 men of the 3rd Vermont Infantry crossed the river to occupy the Confederate works. Col. B. N. Hyde handed Cpl. Alonzo Hutchinson a white handkerchief, which he was to raise and wave as a signal when the works were taken.

With the 3rd was one Private William Scott, who had fallen asleep on guard duty in Washington, D.C., back in 1861. Sentenced to death, he was pardoned by Lincoln and returned to duty.

Muskets held high over their heads, Hutchinson, Scott, and the rest waded into the waist-deep stream. But the Confederates opened the sluices of the upstream dam—raising the water level and ruining much of the ammunition they carried. Hutchinson never got the chance to make his signal. A few Rebel pickets fired into the advancing bluecoats and he was mortally wounded by a Confederate bullet that passed through the colonel’s handkerchief.

Stepping on the opposite bank, the Vermont troops rushed to a line of rifle pits held by the 15th North Carolina of Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb’s brigade. The Federals’ quick sortie across the river surprised the defenders. Their section had been quiet enough that most of the Confederates had stacked their arms while awaiting rations.

Drums beat out the long roll, and the Rebels retrieved their muskets to confront the enemy. Col. Robert McKinney, commander of the 15th North Carolina, was killed. Officers of his regiment told a correspondent of the Petersburg Express that McKinney, “discovering that one wing of his regiment appeared to falter, rushed in that direction, with his cap off, and waved to his men to follow him. This singled him out as a promising mark for the enemy’s sharpshooters, and he fell, mortally wounded.”

Smith’s orders were to occupy the Rebel works only if they were abandoned. Cobb’s Brigade organized a counterattack, and Smith therefore ordered the Vermont troops back across the river.

The brief clash saw 23 men of the 3rd Vermont killed, 51 were wounded, and 9 left behind as missing. Their losses were about half of those suffered by Smith’s brigade that day. Among the dead was Scott.

A dispatch in the Richmond newspapers said the Confederates lost 20 dead and 75 wounded. The Rebel artillery had lost eight horses killed, and a howitzer was knocked out of action.

The day after the clash at Dam No. 1, General Joseph E. Johnston arrived to take command of the Confederate forces. Although the Union Navy was so far reluctant to aid McClellan, the Confederates on the peninsula were potentially in danger on both flanks if enemy gunboats did come up the York and James Rivers. Even if Johnston won a major victory in the field, he could only pursue McClellan only as far as the practically invulnerable Fortress Monroe. There, the Union troops would be safely sheltered and in easy reach of supply vessels and reinforcements. Johnston resolved only to harass and delay the Federal advance as long as possible, allowing the Confederates to bolster Richmond.

Rather than probe the Rebel lines for a weak spot, or rattle the enemy into scattering his forces to deal with simultaneous attacks, McClellan settled into a siege of Yorktown. Work began on the siege lines on April 18 as soldiers made 3,400 gabions—large earth-filled baskets of woven branches lined up or stacked— to build fortifications in quick time. Contributing to the earthworks were 475 fascines (cylindrical bundles of sticks filled with soil). Much of the work was done after sunset to hide the progress of the fortifications from the Rebels. Soldiers also toiled behind the front lines, building corduroy roads and bridges.

Aeronaut Thaddeus Lowe, a well-known American balloonist, was with the Union Army on the peninsula. He made several ascents to observe the Rebel lines, marking the first extensive use of aerial reconnaissance by the U.S. Army.

Also going aloft several times was Brigadier General Fitz-John Porter. On the morning of April 11, Porter went up alone in a balloon to view the Rebels at Yorktown. The single guide rope parted, and the winds pushed Porter toward the enemy lines. He took advantage of the accident to make careful observations of the Confederate lines, until the wind shifted and blew him back over his own lines. Porter, who had learned much about ballooning, then opened a valve to release some of the gas from the balloon. Balloonist and author John Wise later wrote that the balloon descended rapidly, bringing Porter down onto an army tent. Unharmed, but “enveloped in a mass of collapsed oil silk,” Porter crawled out of the tangle and saw that he was in camp 100 yards from McClellan’s headquarters. George Armstrong Custer, then a lieutenant, also made several observation flights, and there was some Confederate ballooning as well around Yorktown.

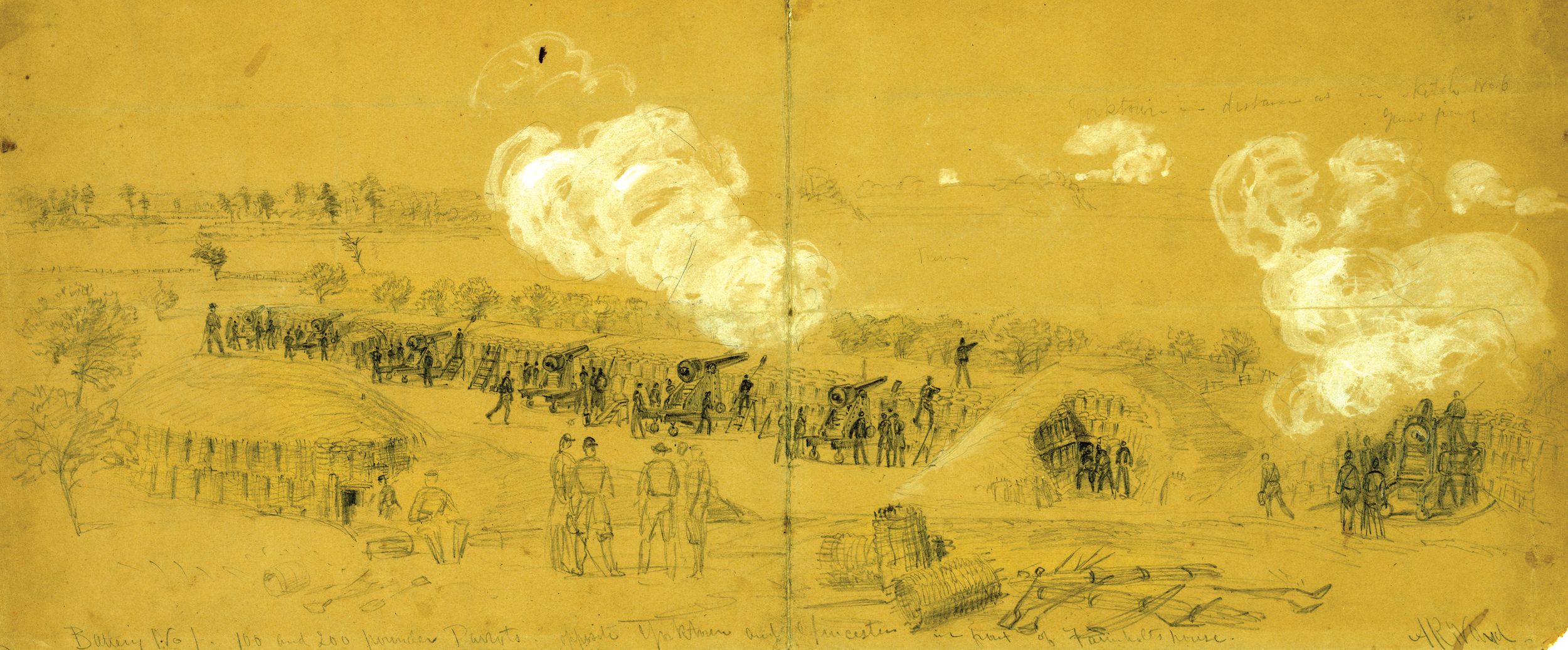

On the ground before Yorktown, McClellan’s men continued with the siege works. The largest Union siege guns were a pair of 200-pounder Parrott rifles, and 10 13-inch seacoast mortars. They were transported by water as far as possible, and with enormous effort, hauled overland to their batteries.

By May 5, McClellan expected that 114 siege guns would be in place, not counting 300 field guns. He planned to open a heavy bombardment with his artillery on that day, and once he judged the cannon fire had weakened the enemy lines, his infantry would push ahead. But, rather than let batteries open fire as they were completed, he allowed some piecemeal firing but held off on ordering a general bombardment until all the guns were in place.

Johnston realized he could not compete with the overwhelming artillery advantage of the Union forces, and that he was out of time for stalling the enemy advance. Late on the afternoon of Saturday, May 3, Johnston’s guns opened a heavy fire. After dark, the Confederates slipped away from Yorktown and moved toward Williamsburg. The next day, it was apparent to the Federals that the Rebels were gone. The troops of “Little Mac” soon placed their flags over the empty works. Left behind were 56 heavy siege guns and their ammunition; however, Johnston had gotten away with all of his field guns.

Johnston’s retreat was slow, bogged down by the continuing rains. Twelve miles from Yorktown, the armies collided in battle at Williamsburg on May 5. This battle left the Union victorious so far as gaining the battlefield, but the Confederates slipped away toward Richmond. McClellan slowly moved up the peninsula after Johnston. By the end of May, the Union soldiers were close enough to the Confederate capital to hear the church bells of Richmond.

In order to save Richmond, Johnston confronted McClellan at the Battle of Fair Oaks (or Seven Pines) from May 31–June 1. The battle itself was inconclusive, but it had two major effects. The first was that, though he hadn’t defeated McClellan, Johnston had blunted the momentum of the Union campaign. The second was that Johnston was wounded badly enough to be replaced by Gen. Robert E. Lee.

For most of June, McClellan hesitated to press his attack while Lee strengthened Richmond’s defenses and prepared a new offensive. In one week, the ensuing “Seven Days Campaign” from June 25-July 1, Lee would unravel all the results of McClellan’s painstaking advance from Fort Monroe. Under Lee, who had a much more decisive style than Johnston, the Civil War in Virginia was set to enter a new and more exhaustive phase.

“Little Mac” survived a storm of criticism for his Peninsula Campaign and remained in command of the Army of the Potomac. He successfully halted Lee’s invasion of Maryland at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. Despite having possession of “the Lost Order”—a captured battle plan detailing the scattered and vulnerable dispositions of the Confederate Army—McClellan failed to defeat Lee on the field and led a lackluster pursuit that allowed the Rebels to escape to safety in Virginia. Lincoln removed McClellan from command on November 5.

During and after the battles of the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days, McClellan’s slow and hesitant maneuvering got him the nickname of “the Virginia Creeper.” At the time “Little Mac” and his 58,000 troops advanced toward and past Yorktown, 110,000 Union and Confederates troops were about to clash at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee on April 6 and 7. Such vast armies were still new to American military commanders. McClellan could certainly envision staggering numbers of dead and wounded soldiers, unprecedented in American history, should he act hastily or without sufficient care. At this early stage of the Civil War, a commander such as McClellan did not realize that the price of victory was just that: casualties on an enormous and once-inconceivable scale.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments