By David Alan Johnson

All the pilots of No. 71 (Eagle) Squadron, Royal Air Force, had been ordered to report to the briefing room on the afternoon of August 18, 1942. As soon as everyone was seated, Group Captain John Peel walked into the room carrying “an armful of maps and a long list of orders.” The squadron had just been transferred from its base at Debden, Essex, down to Gravesend, in Kent, which came as a surprise and also created more than the usual amount of rumors and gossip.

Everyone in the room could not help wondering if this was the beginning of a major operation against the Germans on the Continent—there had to be a good reason for the sudden move to Gravesend. Rumor mongers had been predicting some sort of offensive for quite some time, which was nothing new—they always seemed to be predicting something. The only trouble was that their predictions turned out to be wrong nine times out of 10.

But as soon as Group Captain Peel started talking, it became obvious that the gossips were right this time. On a large map of the Channel coast of France, he began pointing to the port city of Dieppe and spoke about a general plan of attack against German installations in the area. It looked like this really was going to be the big offensive that everyone had been hearing about. A few minutes into the briefing, one of the pilots leaned over to the man next to him and whispered, “This is it!”

The other two Eagle Squadrons—121 and 133—had also been transferred to other bases closer to the Channel coast. No. 121 Squadron was moved to Southend-on-Sea, while 133 Squadron was shifted south to Biggin Hill. All three bases, along with every installation in the south of England, were then isolated. All personnel were confined to base, all leaves were cancelled, and all outside telephone calls required the permission of the station commander.

At similar briefings all along the south coast, the men were told the reason behind all the stealth and secrecy. It was in preparation for Operation Jubilee, which Combined Operations described as “a raid on Jubilee [Dieppe] with its military and air objectives.” The destruction of the Luftwaffe’s airfields and as many enemy aircraft as possible was another of the operation’s objectives. The pilot of 71 Squadron was right—this certainly was it. All three Eagle Squadrons would take part in the operation.

“Second Front Now!”

The Eagle Squadrons existed as a necessity of war. During the Battle of Britain, the Royal Air Force needed pilots desperately—the Luftwaffe was killing pilots faster than the RAF could train them. Because of the shortage, American volunteers were recruited to join the RAF as pilots for both Fighter Command and Bomber Command. The first of the three American squadrons, 71 (Eagle) Squadron, was formed in September 1940, over a year before Pearl Harbor. So many Americans volunteered that two more squadrons were formed, 121 Squadron in May 1941 and 133 Squadron two months later. After the customary training and breaking-in period, all three units became active and operational RAF squadrons.

The basic aim of Operation Jubilee was to make a landing on the French coast, destroy as many German installations, including “aerodrome installations,” as possible, and withdraw. It was a raid, not an invasion. It has also been referred to as a reconnaissance in force.

Even though Operation Jubilee was not a full-scale invasion, it did represent a “second front” of sorts. For several months, the Soviets, along with a few overzealous British and American officers, had been shouting, “Second Front Now!” The Soviets had been demanding any kind of invasion, in France, Italy, or anywhere else, since June 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.

It was hoped that Dieppe would placate the Soviets and would also give senior British and American officers some vital information on German defenses. Dr. Josef Goebbels and his Nazi Propaganda Ministry had been bragging about Germany’s Atlantic Wall defenses since 1940. The raid would allow Allied planners to find out exactly how solid the German defenses really were. This would be useful in planning future operations, especially the anticipated D-Day landings that would take place two years later.

Flying Cover For the Dieppe Raid

A total of 48 Supermarine Spitfire and eight Hawker Hurricane squadrons—including the Eagle Squadrons—would be flying fighter cover for the landing forces, providing an air umbrella over the beaches. The fighters had two jobs: to keep the Luftwaffe away from the landing beaches and to inflict maximum damage to the enemy’s fighter and bomber forces. The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses of the recently arrived 97th Bomb Group, U.S. Army Air Forces, would also be taking part in the operation. The 97th Bomb Group had been given the vital assignment of knocking out the Luftwaffe fighter base at Abbeville for several critical hours during the raid.

“On the morning of the Dieppe Raid we were all up before dawn and having had breakfast were at dispersal at first light.” The commander of a British fighter squadron made this entry in his logbook on the morning of August 19, 1942. For most fighter units, including the three Eagle Squadrons, the operational day on August 19 began at the uncivilized hour of 4:45 am. After breakfast, the pilots climbed into their Spitfires, started their engines, and began climbing toward the Channel coast at 2,500 feet per minute.

From Gravesend, 71 Squadron joined five other Spitfire squadrons over Beachy Head on the Sussex coast. All six squadrons—a total of 72 Spitfires—headed across the Channel to Dieppe.

Pilot Officer Harold Strickland, who had begun flying in Texas before the war, became separated from the rest of 71 Squadron because his wingman could not retract his landing gear. Everyone had been briefed to observe strict radio silence throughout the raid, but Strickland sent the pilot back with a two-word radio transmission. He did not say exactly what the transmission might have been, but it was probably something like “Go home!”

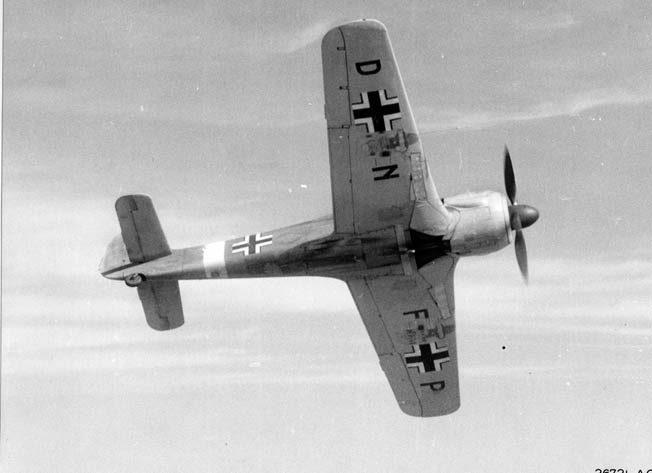

With his wingman safely sent back to Gravesend, Strickland pushed the throttle all the way forward and tried to catch up with the rest of his squadron. By that time, 71 Squadron “had turned off their small blue navigation lights and disappeared.” He did manage to find four German Focke Wulf FW-190 fighters west of Dieppe in the half-light just before dawn and took a shot at one of them before they disappeared.

Pilots could see the gunfire from the German defenders at Dieppe along with the naval gunfire from the Allied warships just offshore. The attacking forces consisted of about 5,000 Canadian troops, 1,000 British commandos, and 50 U.S. Army Rangers. These were supported by 252 naval vessels—none larger than a destroyer —along with 69 air squadrons.

“I saw the flashes of heavy gunfire to my left, which was towards the sun,” Strickland wrote in his diary. He spotted four aircraft in the semi-darkness and flew toward them. As he closed in, Strickland identified them as FW-190s. “I attacked the No. 4 with cannon and m.g. with about 45-degree deflection and saw my explosive shells strike the fuselage.” The stricken FW-190 dived; the other three turned on Strickland. He headed for the layer of cloud that covered the French coast that morning and neatly evaded them. “Landed at Gravesend just before dawn,” he succinctly ended his report.

Spitfires vs the Abbeville Boys

The Luftwaffe was coming up to fight in force, even at this early stage of the operation. Radar stations in southern England began detecting large plots of enemy aircraft at around 7 am, mostly in the vicinity of Abbeville and St. Omer. These were the pilots of Jagdgeschwader 26, the “Abbeville Boys,” who flew from several bases in the area.

A major part of Germany’s fighter force had been transferred to Russia by the summer of 1942. But the Abbeville Boys were still in northern France and were some of the best pilots in the Luftwaffe. Their commander was Adolf Galland. Galland was not only an outstanding pilot but also one of the best shots in the Luftwaffe. He was credited with destroying more than 100 Allied aircraft and managed to survive the war.

The pilots of 121 (Eagle) Squadron arrived over Dieppe at around 9 am. The squadron was headed by Squadron Leader Bill Williams, a British officer; the American commander, Hugh Kennard, had been grounded by illness for over two weeks. By the time 121 reached Dieppe, the Luftwaffe was already up and waiting. “Dogfights ensued,” noted 121 Squadron’s log book, “and the Squadron became split up and returned to base in ones and twos.”

The Abbeville Boys were clearly getting the better of the Spitfire pilots. During the course of one particularly violent action, five Spitfires were shot down and a sixth was badly damaged by cannon fire. The Luftwaffe lost two or three FW-190s, depending on which source is consulted. The Focke Wulfs were showing a decided superiority over the Spitfire Mark Vs.

Three of 121’s pilots did not return to base after this encounter: one was killed, one was rescued from the Channel, and one was shot down over France and taken prisoner. Another pilot managed to bring his Spitfire back to base literally covered with bullet holes. The fighter had cannon shell holes in its fuselage and wings, its instrument panel, and even its plexiglass cockpit canopy.

In return, 121 could claim only one enemy fighter destroyed along with two probables and one damaged. This certainly came as a major disappointment. The squadron had been waiting for the Luftwaffe to show itself for the past few months. When the Germans finally did come up to fight, the squadron ended up losing a quarter of its pilots in one encounter.

The Germans were proving to be a lot better than everyone expected. They were not only murderous shots, but also had the knack of being able to dodge and evade the Spitfires whenever an RAF pilot made a firing run. Enemy fighters frequently could not be kept in the gunsight long enough for a pilot to get off a good burst. One entry in 121’s logbook noted, “A number of pilots fired their guns but made no claims.”

“Who Needs Enemies When We’ve Friends Like That?”

Enemy fighters were not the only menace to the Spitfires. While 71 Squadron flew toward Dieppe over the landing force, several offshore LCRs (Landing Craft, Rockets) began firing at targets just inland from the invasion beaches. The LCRs carried well over 100 mortar-like rockets. These were usually fired in salvos—all the rockets on board were shot off in less than a minute.

None of the pilots could tell if the rockets were hitting their targets, but they could not help noticing that about 50 of them passed right through their formation. Although “a few came uncomfortably close,” all of the rockets missed the Spitfires. “All the rockets continued to their apogee and duly plunged to earth somewhere off to port,” Wing Commander Miles Duke-Woolley, who flew with 71 Squadron at Dieppe, later reported, “and a quick check showed that we remained not merely intact but untouched.”

Everyone realized that a direct hit by one of the rockets could have made “a considerable mess of your aircraft”—a classic example of British understatement. To relieve the tension, someone made a crack over the radio, “Who needs enemies when we’ve friends like that?” Duke-Woolley said that the remark “expressed our collective thoughts.”

Outclassed by German FW-190s

Throughout the morning, radar stations in England continued to monitor enemy air activity across the Channel. By 9:41, more than 20 enemy aircraft were plotted in the vicinity of Abbeville. Another 20-plus appeared on radar screens about five minutes later. The Luftwaffe was certainly coming up to challenge the RAF and coming up in strength. The bases at Abbeville, St. Omer, and others in the area were only about 30 miles from Dieppe. This meant that the German pilots were only a few minutes’ flying time from the landing beaches, which allowed them to use most of their fuel maneuvering against the Spitfires.

The pilots of the three Eagle Squadrons had seen mostly fighters over Dieppe so far, but German bombers began to make their presence known shortly after 9 am. The first of the Eagles to make contact with enemy bombers was 133 Squadron, led by Flight Lieutenant Don Blakeslee. This took place on 133’s second sortie of the day. The squadron had already claimed two FW-190s destroyed and one probable on its first trip to Dieppe.

On this sortie, 133 had been assigned to fly top cover for the Allied shipping just off the beaches. The Navy was doing its best to get in as close as possible to pick up survivors of the landings. German bombers were just as determined to break through the fighter cover and make their bombing runs at the ships as they moved close to the beaches.

At about 12,000 feet, 133 Squadron, along with several other Spitfire units, ran into a large flight of German aircraft—Junkers Ju-88s, Dornier Do-17s, and a good many escorting fighters. The Spitfires went after the bombers, while the German fighters did their best to intercept the Spitfires. But 133 reached the bombers first and started shooting as soon as the pilots were within range. A Ju-88 fell out of formation almost immediately, trailing smoke. The pilots of 133 claimed one Ju-88 and two FW-190s destroyed, as well as several other German aircraft damaged.

Number 133 was one of the few RAF squadrons that was having a good day. Most units ran into lethal opposition from the Luftwaffe and, as one squadron leader put it, “Our Spitfire 5s were completely outclassed by the FW-190s.” The Abbeville Boys were certainly living up to their reputation as one of the premier units in the Luftwaffe. They could see that they had the upper hand and were going after the Spitfires with single-minded determination.

The situation on the ground offered no improvement over what was happening in the air above Dieppe. Infantry units were also encountering German opposition, usually described as “heavy,” and were having a hard time just getting off the beach.

“It’s Like a Goddam Fourth of July”

By mid-morning, the Dieppe raid was already in serious trouble. More than two-thirds of all Canadian troops had either been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner during the first six hours of the assault. A bad situation was made even worse by the fact that there was no heavy naval gunfire to support the troops, only the 5-inch guns of the destroyers. By 11 am, the decision was made to withdraw all troops from the beachhead.

“The general scene over the beaches was pretty chaotic,” an RAF wing commander later reported. “The shipping off shore was wreathed in smoke as it bombarded targets behind the town … Most of the time at least one aircraft could be seen spinning or diving down somewhere in a trail of smoke or flame.”

The log book of 71 Squadron recorded, “Two ships were seen on fire in the harbor.” Chesley Peterson, the commander of 71 Squadron, gave a description that was more to the point: “It’s like a goddam Fourth of July.”

The USAAF 31st Fighter Group

The three Eagle Squadrons were not the only Americans in the air over Dieppe on August 19. The 31st Fighter Group, U.S. Army Air Forces, which had arrived in the British Isles only a few weeks before, flew a total of 123 sorties over the landing beaches that day. Like the Eagles, the 31st also flew Spitfire Vs. The two prevalent American fighters of the time, the Bell P-39 Airacobra and Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk, were no match for either the German Messerschmitt Me-109 or the FW-190. These “American Spitfires” were marked with the white U.S. star, which had been painted over the red, white, and blue RAF roundel.

None of the pilots had been in combat before; the Abbeville Boys gave them a very harsh indoctrination. Eight of the 31st’s Spitfires were shot down, with five of its pilots missing. The new pilots did enjoy some success that morning. Second Lieutenant Sam Jankin shot down a FW-190, the USAAF’s first enemy aircraft destroyed over Europe. But Lieutenant Jankin was shot down himself a short time later and was rescued from the Channel later in the day.

German intelligence apparently did not realize that the Americans were flying Spitfires. When Oberleutnant Rolf Hermichen of Jagdgeschwader 26 shot down a fighter marked with the U.S. insignia, he claimed a P-39 Airacobra destroyed. No P-39s were in the air over Dieppe.

Circus No. 205

Twenty-four B-17 Flying Fortresses of the U.S. 97th Bomb Group also had been assigned to fly operations over Dieppe. The 97th had flown its first operation only two days earlier, against the Rouen-Sotteville marshaling yards. That had been an easy trip—a “milk run,” in the jargon of the Eighth Air Force. Their current assignment did not look like another milk run. The official name of their operation was “Circus No. 205,” a misleadingly innocent name for a potentially deadly job. The objective of Circus No. 205 was nothing less than the Luftwaffe fighter base at Abbeville.

With four squadrons of RAF Spitfires for an escort, the Flying Fortresses set out from their bases in England and headed south toward the Sussex coast. Senior USAAF officers had high hopes for their top secret Norden bombsight, which was supposed to allow a bomb aimer to drop his bombs into a pickle barrel from thousands of feet above the target. With this operation, the generals and senior planners would be able to determine if the Norden lived up to all the hype. If the bombsight allowed the 97th Bomb Group to knock out Abbeville’s runways for several critical hours, the generals would be well satisfied that the Norden was as good as its publicity.

The Fortresses crossed the French coast shortly after 10 am and arrived over Abbeville six minutes later. The bombers had to contend with antiaircraft fire throughout the entire six minutes but met hardly any fighter opposition. A top turret gunner in one of the B-17s fired a burst at an “unidentified fighter.” The tail gunner of another Fortress chased an Me-109 by firing in the fighter’s direction. But the German fighter pilots were surprisingly hesitant when it came to attacking the American bombers.

This reluctance was partly because the fighters were preoccupied—a flight of RAF Douglas Boston bombers was also in the area—and also because no one knew very much about the Fortresses. Their reputation was formidable—they were said to be very large, very fast, extremely well armed with a dozen or so .50-caliber machine guns, and able to take a lot of punishment. The German pilots could see for themselves that the Forts were big, fast, and intimidating. No one wanted to get too close to all those machine guns.

The Luftwaffe would learn all about the Flying Fortress, especially about its strengths and its weaknesses, in the very near future. When that happened, all diffidence would come to a sudden end. But over northern France on August 19, 1942, the B-17s led a charmed life.

Escorting RAF pilots watched the bombing of Abbeville with approval, if not admiration. A pilot with 401 Squadron observed “many direct hits … on admin area, and also on the southern runway.” Another pilot observed that the Forts “successfully bombed from 23,000 feet.” The results were certainly successful enough to put two of the fighter base’s three runways out of action, which effectively shut it down for two hours, exactly what the brass wanted.

Number 71 Squadron’s Second Sortie

Number 71 Squadron left on its second trip to Dieppe at 10:45 am. Pilot Officer Stanley M. Anderson wrote this short but to the point entry in his logbook: “Airborne Gravesend 1045—Beachy Head 1100—Convoy 1120. Our job to protect shipping—town on fire—resistance is evident.”

A third sortie followed. Pilot Officer Anderson went on to give more details about the morning’s air battle. “Plenty of FW-190s, Ju-88s, Do-17s, and Me-109s—took a crack at a Ju-88 damaging it and killing the rear gunner. CO [Squadron Leader Chesley Peterson] and Mike [“Wee Michael” McPharlin] shot down but were picked up by air sea rescue. Plenty of fun and games for all.”

In the vicinity of Dieppe, Oscar Coen and “Wee Michael” McPharlin went after a formation of three Ju-88s and set one of them on fire. They did not actually see it crash, though, and could only claim it as a probable.

Peterson in the Channel

The squadron leader, Chesley Peterson, singled out a Ju-88. “I fired at one of the 88s, diving at him opening fire at 300 yards astern. I saw cannon strikes, mainly on the starboard wing, and his starboard motor emitted puffs of black and white smoke.”

But that was not the end of the confrontation. “As I closed to 200 yards, the rear gunner started shooting and hit my aircraft,” Peterson later wrote. “I knew that I was hit and that I would have to bail out anyway, so I kept firing up to 150 yards, and then I had to quit as there was so much steam and smoke in the cockpit.”

Peterson received credit for the Ju-88. Wing Commander Miles Duke-Woolley confirmed that the bomber crashed into the sea. But Peterson’s Spitfire had also been badly damaged—the Ju-88’s rear gunner had set his engine on fire. He jettisoned the cockpit canopy, climbed out of the fighter, and jumped. He remembered, “I saw my Spitfire hit the water with a great splash.” He descended toward the cold Channel waters.

On his way down—the descent took about 10 minutes—Peterson remembered that he still had his revolver tucked away in his flying boot. He was about to throw it away when it occurred to him that he had never fired it. Before tossing it into the Channel, he decided to empty the revolver, firing all the rounds into the air. Satisfied, he dropped the gun and watched it fall toward the icy gray water. A few minutes later, Peterson was in the water as well.

Within a fairly short time, Peterson was rescued by a patrol boat. Even though he had been picked up and was on his way back to England, Peterson was still not out of danger. The boat was strafed by a German fighter. Another RAF pilot on board, who had also been rescued from the Channel, was killed. Peterson did make it back to England and eventually back to 71 Squadron.

Wee Michael McPharlin “Full of Benzedrine”

McPharlin was also shot down by the rear gunner of a Ju-88. Actually, the gunner knocked out McPharlin’s compass. A flight of FW-190s forced him to take cover in the clouds, where he completely lost his bearings. When he came out of the cloud cover, McPharlin discovered that he was almost out of fuel. He bailed out of his fighter when it finally did burn up all of its gasoline and came down in the Channel only about three miles off the coast of France.

McPharlin spent his first few minutes in the Channel trying to clamber into the inflatable single-seat dinghy that all the pilots carried as part of their parachute pack. As he bobbed up and down in the current, the coast of France was clearly visible, which meant that he was much too close to the Germans for his personal comfort. The only way to avoid capture, it seemed, was to start paddling north toward England.

The trip was a lot longer—and would take a lot longer—than it looked. After only a few minutes of paddling, McPharlin could see that he would be needing an energy boost if he was to have any hope of making the trip. So he broke into his escape kit, where he found a supply of Benzedrine, and promptly downed the entire supply.

Benzedrine had a reputation for being an excellent stimulant; the pills certainly stimulated McPharlin. According to his wing commander, Wee Michael was “supercharged with zeal, and feeling that for hours he would become a human dynamo, he thrashed away with the hand paddles. One suspects he resembled a sort of static whirling dervish.” Happily for him, an Air Sea Rescue launch spotted him after only about 20 minutes in the water. He was safely back at Debden that night.

Everyone in 71 Squadron was fully aware that Wee Michael was “still full of Benzedrine” by the fact that he was still propped up at the bar at 2 am. The medical officer advised that McPharlin might go on “at full throttle” for another 48 hours before going out like a light. So the pilots took turns keeping an eye on him. Nobody knew when he might collapse.

As the third night was approaching, Wee Michael finally conked out. “Suddenly, and in mid-pint, he crumpled like a wet flannel” right onto the floor of the bar. His squadron mates carried him out and “poured him into bed.” For the next 24 hours, McPharlin was absolutely dead to the world. When he finally did wake up, he showed absolutely no ill effects from the Benzedrine—no headache, no nausea, no hangover, nothing. According to Wing Commander Duke-Woolley, “Our faith in Benzedrine zoomed.”

The Last Sortie Over Dieppe

Of the three Eagle Squadrons, both 71 and 133 Squadrons had flown three sorties over Dieppe by evening, while 121 had flown two. The raid was over by the time 71 Squadron arrived above the landing area at around 5:45 pm. All the assault boats were away from the beaches and headed back toward England. A formation of FW-190s came into sight as the Eagles flew top cover over the evacuation, and the pilots maneuvered into position to attack. But as soon as 71 Squadron turned into the Focke Wulfs, the Germans retreated inland and the Eagles resumed their patrol over the Allied ships. When they returned to Gravesend after their patrol, it was nearly dark. The Spitfires were rearmed and refueled in preparation for night operations.

“We arrived over Dieppe to find all of our assault boats and transporters away from the beaches and on course for England,” Harold Strickland noted in his diary. “We set course for home and landed at Gravesend, re-fuelled, re-armed, and prepared for night fighting.”

As it turned out, there would be no night fighting for 71 Squadron. But while the squadron’s Spitfires were being readied for the next day’s operations, Don Blakeslee was taking 133 Squadron back to Dieppe for its fourth sortie. The planes arrived at about 8 pm. By that time, the landing force had been completely evacuated, and most of the Luftwaffe had returned to its bases.

But not every German fighter had gone home, not even at that late hour. The pilots who were still in the area of Dieppe were full of fight. “On the fourth show of the day we were attacked by 2 FW-190s who came from above and fired on us,” 133’s Richard “Dixie” Alexander wrote in his report. He turned on one of the Focke Wulfs and chased it down to about 3,000 feet, firing all the way. Alexander barely managed to avoid crashing and was reasonably sure that the Focke Wulf did not pull out. Because he knew he had damaged the enemy fighter with his cannon fire, he could see his cannon shells strike the plane, Alexander claimed it as a probable.

This was likely the last action of the long day. The Spitfires of 133 were the last fighters down, landing at Lympne at 8:55 pm. The Eagle Squadrons had flown both the opening and the closing sorties of Operation Jubilee. At dawn, 71 Squadron was the first to see combat, and 133’s encounter with the FW-190s came after dark.

The pilots of 133 Squadron enjoyed a profitable day over Dieppe. “Every dog has its day,” crowed the squadron’s logbook, “and on 19 August, 133 was the dog.”

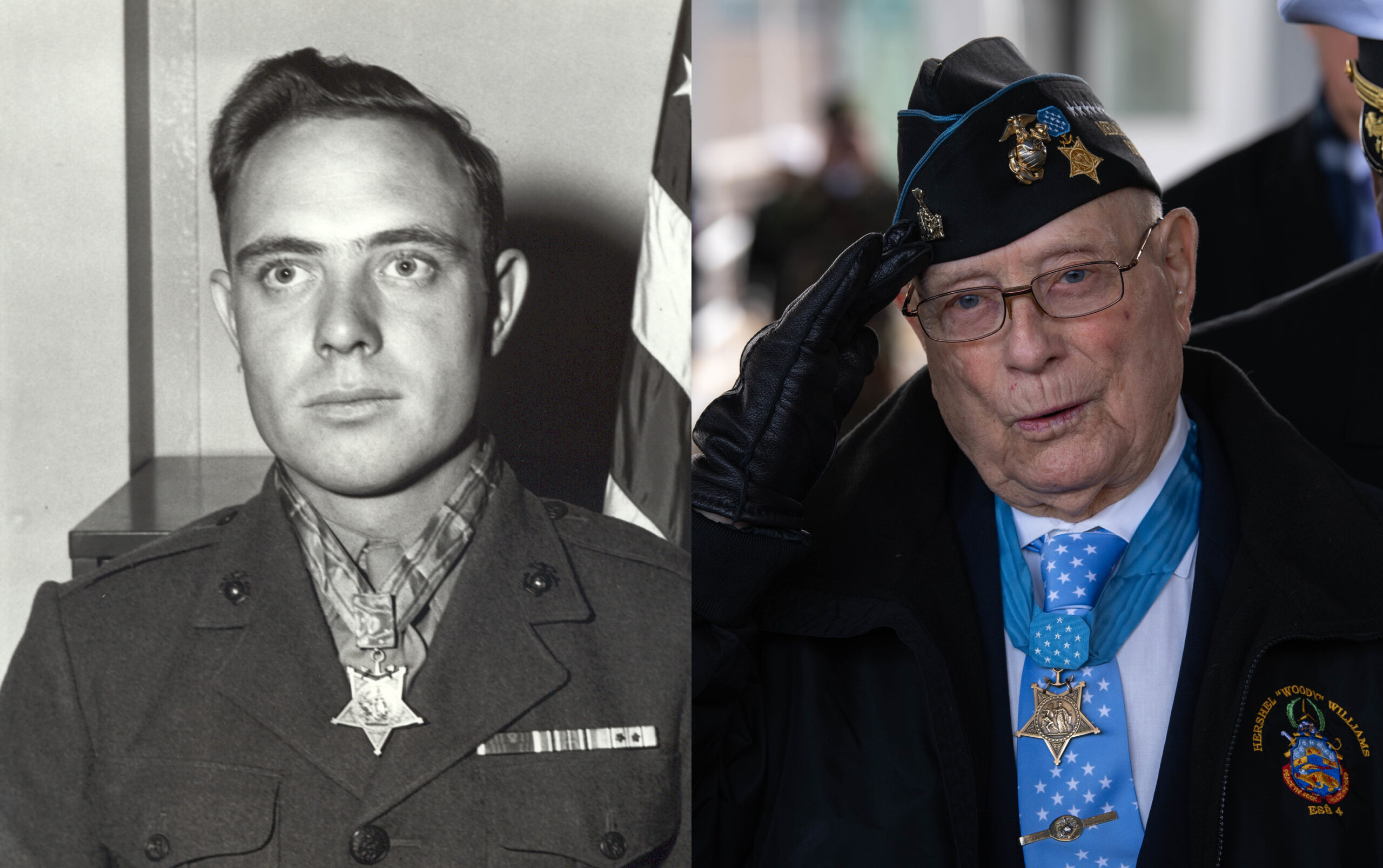

Number 133 entered claims of six enemy aircraft destroyed, two probables, and eight damaged (claims that were later officially changed), with no losses of its own. Don Blakeslee had the best score. He claimed a German aircraft destroyed on each of thes squadron’s four trips to Dieppe, which was later changed to one destroyed and two damaged. Blakeslee and 133 were one of the few RAF units to come out ahead on August 19.

The air battle had been visible to hundreds of people in southeastern England. Crowds of spectators gathered along the Channel coast to watch the Luftwaffe and RAF twisting and turning in their deadly maneuvers. This was the first time since the Battle of Britain, two years before, that such fighting had been visible. One of the best vantage points was the high ground at Beachy Head in Sussex. The white contrails could be clearly seen against the blue summer sky.

“The planes in their hundreds made the sky alive with action, speed, and noise,” a reporter from the Brighton and Hove Herald noted. “Bombers and fighters were seen, some engaged with enemy planes and many a swift aerial battle was fought within sight of the eager watching crowds.”

Six Kills and Six Losses

The Dieppe raid had certainly succeeded in bringing the Luftwaffe out. Nearly 1,000 sorties had been flown by German pilots—145 by twin-engine bombers and the rest by fighters. Because the Luftwaffe airfields were only a few minutes away from Dieppe, most German fighters were concentrated over the landing beaches. This concentration gave the Luftwaffe numerical superiority over the RAF in just about every encounter. A German historian had this to say about the air battle of August 19, 1942: “The Dieppe raid was, from the point of view of the German fighter pilots, one of the happiest days since the Battle of Britain.”

Total German claims were 112 aircraft shot down. Official lists of RAF losses differ among themselves, but author Norman Franks, in his book Greatest Air Battle, gives them as 97 aircraft lost to enemy action, along with 51 pilots killed in action and 17 captured. The Luftwaffe’s top scorer was Josef Wurmheller of Jagdgeschwader 2, who was credited with six Spitfires and one Blenheim bomber destroyed.

Combined losses among the three Eagle Squadrons came to six Spitfires destroyed and four damaged. The hardest hit of the three was 121 Squadron, which lost four of its 12 Spitfires, along with two others damaged. Also, one of 121’s pilots was killed (James Taylor) and another was taken prisoner (Barry Mahon).

As far as claims that were actually confirmed, the combined score of the three Eagle Squadrons totaled six enemy aircraft destroyed (one by 71 Squadron, one by 121, and four by 133).

The Eagles had never encountered the enemy in such force prior to Dieppe. They had seen Messerschmitts and Focke Wulfs in small groups during fighter sweeps over the Continent, usually in pairs or in small formations. The confrontation over Dieppe came as a sobering experience.

The battle also came as a nasty shock to the pilots of the U.S. 31st Fighter Group, which lost eight Spitfires on August 19. They found out the hard way that they had a lot to learn about aerial combat, and also that the Germans, especially the Abbeville Boys, were a lot better than they had been led to believe.

The Eagles Transfer to the USAAF

All three Eagle Squadrons were back in the air the next day, August 20, with no time off. Their main activity was escorting bombers on strikes over northern France and keeping a sharp eye for enemy fighters. But the Luftwaffe stayed on the ground. Squadron logbooks complained, “No enemy aircraft seen.”

It was as though the Luftwaffe had made its point on August 19—that it was still very much alive, still as full of fight as ever, and still more than capable of challenging either the British or the Americans any time it chose.

The Eagle Squadrons continued to fly operations throughout the summer of 1942, but their days as members of the Royal Air Force were numbered. By mid-September, the first group of Eagle Squadron pilots was commissioned into the U.S. Army Air Forces. The next time the Eagles flew together in the same operation following Dieppe, they would be members of the U.S. Fourth Fighter Group.

The three Eagle Squadrons finally left the RAF on September 29, 1942, in a ceremony at Debden, Essex, that was filled with speeches and fanfare. Number 71 Squadron had become the U.S. 334th Squadron, 121 Squadron was now the U.S. 335th Squadron, and 133 Squadron was the U.S. 336th Squadron. By the end of the war, these three fighter units had become the top scoring American squadrons in the European Theater of Operations, with a score of 583½ enemy aircraft destroyed in combat and another 469 on the ground, for a total of 1,052½.

“The Whole Operation Was an Extraordinary Nonsense.”

Over the years, historians have generally considered the Dieppe raid a disaster. Wing Commander Duke-Woolley certainly agreed with that judgment. He admitted that the raid on Dieppe completely baffled him. “It was large enough to invite heavy casualties,” he said, “but too small for the Germans to consider it an ‘invasion’ of any sort.”

If he had been given his way, the main effort of the RAF and the USAAF would have been to make repeated attacks on the airfields near Dieppe, “notably that at Abbeville with whose fighters we had tangled on sweeps, and to have made it thoroughly unpleasant by repeated attacks on and around them.” Duke-Woolley also talked about Operation Jubilee with what he referred to as his “contemporaries at Fighter Command,” and came to the conclusion that “the whole operation was an extraordinary nonsense.”

Pilot Officer Harold Strickland took the opposite point of view. Strickland was of the opinion that Dieppe was instrumental to the success of the D-Day landings in June 1944. “Operation Jubilee in 1942 had conditioned the German strategists to believe that the logical site for the main landing of the invading forces would be in the Pas de Calais area, and Normandy was a diversion,” he said. This diversion, along with the sacrifices at Dieppe, “saved thousands of Allied lives directly and indirectly during June 1944 in Normandy.”

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, who led the planning for Operation Jubilee, agreed with Strickland. In 1973, Mountbatten told a group of Canadian veterans, “The Duke of Wellington … said that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eaton. I say the successful landing in Normandy was won on the beaches of Dieppe.”

The news media in both Britain and the United States also emphasized the fact that the Allies had staged a successful landing on the enemy coast and hinted that Dieppe had served as a dress rehearsal for a much larger and more ambitious invasion in the future. Newspapers tended to play down the casualties and losses of the operation.

Over the years since 1942, historians have discussed the lessons of Dieppe and have argued at length exactly how much was gained and how much was lost as a result of the operation. To the pilots of the three Eagle Squadrons, Dieppe was the biggest air battle they had ever taken part in. But most of them were too young and too preoccupied to reflect on how that battle might have affected the outcome of the war.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill probably gave the best summing up of the Dieppe raid. “Honour to the brave who fell,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Their sacrifice was not in vain.”

I think that every landing whether successful or not prior to D Day was a learning experience for the Allies for the future. Knowledge comes in many ways. By what you get taught or by what you must learn yourself, no matter how bloody the lesson is. Those who died at Dieppe did not die in vain.

Good detailed article

Early the next year (1943) after Operation Torch is over GEN Patton reflects, “If we had be fighting Germans we would have never gotten ashore.” There is a lot of learning still ahead before the two prime allies learn to be allies and not mere co-combatants as is the Axis.

Neptune/Overlord still has many problems and blunders – notable among them is Omaha beach untouched by pre-invasion bombardment. Yet it prevails and does so for many reasons, most of them right there on the five invasion beaches.

So the real questions to ask is would we have been prepared for the largest invasion in history Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan, and if we did EVERYTHING right would the invasion have been successful anyways.

Good article, thank-you.

Thanks for a very informative article on the Dieppe Raid. It was more detailed than I have read about before. That the Luftwaffe put such a huge effort that early shows how large and determined their forces already were in France in 1942, and how our bomber forces flying missions later would have few or no “milk runs” as the Army Air Force pursued its massive daylight bombing campaign in Northwest Europe. Also, it provided good “practice” for our Eagle Squadron and 31st Fighter Squdron to let them find out the skill of the German pilots. Of course, the FW-190 was superior to the ME-109 and it showed in these sorties when handled by skilled pilots – another item for our pilots to chalk up to experience needed later on. The photo of Don Blakeslee was probably taken later, as he is still wearing the RAF headset but in a US flying helmet, along with USAAF goggles and A-10 oxygen mask. Possibly he was in a P-51 Mustang, which the USAAF 4th Fighter Group eventually was equipped with (it would’ve required US-designed oxygen mask connections).

The Canadians were sacrificed at Dieppe.

I think that the whole war could have been easier if more emphasis was placed on the B-25, outfitted with 8 .50 cal. machine guns in the nose, and others in the turrets, and also stuffed with fire bombs, which would be more devastating than high-explosives, since the fires would spread, and the B-25 could also be its own fighter escort, or cover each other, and be simply devasting in any capacity, either as a fighter or bomber.