By Clark Larsen

“Early in the year 1861, I was at my headquarters in the city of Chicago, attending to the manifold duties of my profession. I had, of course, perused the daily journals which contained the reports of doings of the malcontents of the South, but in common with others, I entertained no serious fears of an open rebellion, and was disposed to regard the whole matter as of trivial importance.” Thus wrote Allan Pinkerton, detective, just before being summoned to a duty that soon had critical national ramifications.

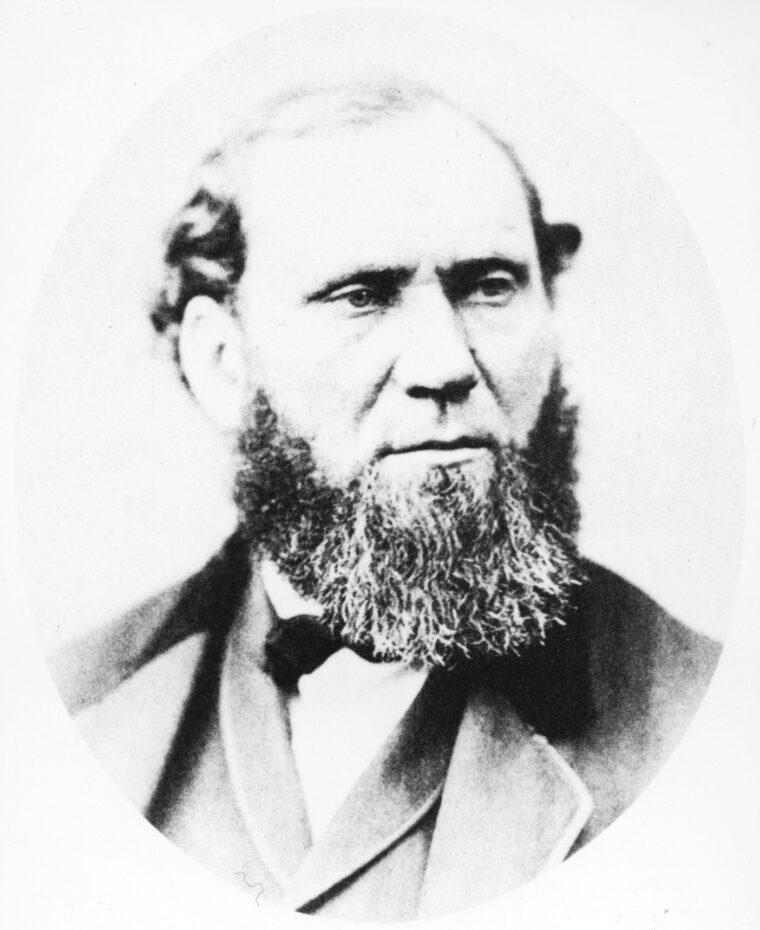

Pinkerton was a Scot by birth, an agitator for workers’ rights in his homeland, which more or less led to his immigration to America; a cooper by trade who by chance and then diligence discovered a band of counterfeiters; and then became a police detective and private detective in Chicago. He had a knack for turning up concealed information.

In early 1861, Samuel Morse Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad wrote Pinkerton, asking him to investigate reported Secessionist plans to disrupt rail traffic on his line. Pinkerton accepted the work, and in February he and his operatives began infiltrating the Maryland Secessionist movement. Timothy Webster was assigned Perryville; John Seaford was sent to Magnolia; another operative was placed in Havre de Grace; and Pinkerton himself went undercover in Baltimore.

The Baltimore police were under the supervision of Marshal George P. Kane. The marshal’s force would be of no help to Pinkerton because it was almost entirely made up of men of dis-union proclivities. Pinkerton sent for additional operatives from his Midwest agency and set them to work in Baltimore.

Before long one of his best detectives, a man to whom he gave the cover name Joseph Howard, had infiltrated Kane’s inner circle. Howard was taken by the marshal to a meeting where he was introduced to Cipriano Ferrandini, a Corsican immigrant, a barber by trade, and a captain in the Nights of the Golden Circle, a secret Confederate organization. Howard later introduced Pinkerton to Ferrandini and they then learned of a plot to assassinate president-elect Abraham Lincoln as his train stopped in Baltimore, the first large city in slave territory to be visited by the president-elect. The plot was fully matured, lacking only the selection of the man to perform the deed.

Pinkerton had also sent for Mrs. Kate Warne, the senior female detective at Pinkerton’s Chicago firm. Warne was an attractive, commanding person with an easy manner, and within days of her arrival she had cultivated the acquaintance of the wives and daughters of the conspirators. Her reporting was invaluable in confirming the information being gathered by Howard, Webster, and others.

On February 18, as Lincoln’s train traveled across New York, Jefferson Davis in Montgomery, Ala. took the oath of office as President of the Confederate States of America. Passions were running high and, despite Lincoln’s stance of moderation, many hated him thoroughly. That night Howard was taken to a secret meeting of the conspirators where he was sworn in as a member. He was warily congratulated by members of the polite circles of Baltimore society, whom he had previously met.

Then the meeting got down to business. A box containing lots was prepared. Each man was to keep secret the color of paper he drew out. The man who drew the red lot was to be the assassin. The leaders, doubting the courage of all present, and to ensure success, secretly placed eight red lots in the box. The room was darkened so that no one would see the color of the lot drawn by another. Thus each man drew a red lot and believed he would be the lone assassin.

Pinkerton had little time to spare because Lincoln was already on his way to Washington. His trip included speeches in major northern cities, shaking thousands of hands, and greeting people at every whistle-stop en route to the nation’s capital.

Three years later, in 1864, President Abraham Lincoln talked with historian Benson J. Lossing about the so-called “Baltimore Plot.”

“I arrived at Philadelphia on the 21st. I agreed to stop over night, and on the following morning hoist the flag over Independence Hall. In the evening there was a great crowd where I received my friends, at the Continental Hotel. Mr. Judd, a warm personal friend from Chicago, sent for me to come to his room. I went, and found there Mr. Pinkerton, a skillful police detective, also from Chicago, who had been employed for some days in Baltimore, watching or searching for suspicious persons there. Pinkerton informed me that a plan had been laid for my assassination, the exact time when I expected to go through Baltimore being publicly known. He was well informed as to the plan, but did not know that the conspirators would have pluck enough to execute it. He urged me to go right through with him to Washington that night. I didn’t like that. I had made engagements to visit Harrisburg, and go from there to Baltimore, and I resolved to do so. I could not believe that there was a plot to murder me. I made arrangements, however, with Mr. Judd for my return to Philadelphia the next night, if I should be convinced that there was danger in going through Baltimore. I told him that if I should meet at Harrisburg, as I had at other places, a delegation to go with me to the next place, [Baltimore], I should feel safe and go on.

“When I was making my way back to my room, through crowds of people, I met Frederick Seward. We went together to my room, where he told me that he had been sent, at the insistence of his father [Lincoln political rival William Seward] and General Scott, to inform me that their detectives in Baltimore had discovered a plot there to assassinate me. They knew nothing of Mr. Pinkerton’s movements. I now believe such a plot to be in existence.”

As he spoke at Independence Hall the next morning, Lincoln seemed to have the assassination threat in mind. He talked first of the Declaration of Independence, and then said: “It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance…. But, if the country can not be saved without giving up that principle—I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this spot than surrender it.”

That night, under cover of darkness, Lincoln took a special train from Harrisburg to Philadelphia, and the regularly scheduled passenger train, not the “Presidential Special,” from there bound for Washington. Both Allan Pinkerton and Ward Hill Lamon, a personal friend and former law partner of Lincoln’s, accompanied him on the trip. Lamon was almost as tall as Lincoln, and on that trip was a walking arsenal. He carried two pistols, two derringers, and two large Bowie knives. He even offered one of his pistols to Lincoln, who declined. To prevent word of the president-elect’s early departure from reaching the assassins, Pinkerton had arranged with E.S. Sanford, general superintendent of the American Telegraph Company, to have the telegraph lines out of Harrisburg cut.

As Lincoln walked to the PW&BRR train in Philadelphia, he leaned on Allan Pinkerton to diminish his height and conceal his identity. According to Lafayette Baker, a chief Pinkerton agent, the ploy worked well—an attendant remarked to Lincoln, “Old fellow, it’s well for you the train was detained tonight, or you wouldn’t have gone in it.”

To ensure he wasn’t recognized on the train, arrangements were made for Lincoln to travel in the last sleeper car. Mrs. Warne had previously reserved the rear berths there, saying they were for her “invalid brother and his party.”

Unknown to either Lamon or Pinkerton, another armed man traveled that night in the same car. William H. Seward, former governor of New York, and Winfield Scott, General-in-Chief of the United States Army, had heard rumors of trouble in Maryland too. At their request, John A. Kennedy, superintendent of the New York City Police Department, had assigned detectives to go undercover around Baltimore. It was their information that Frederick Seward had reported to Lincoln the night before. Kennedy was hurrying to Washington to warn the authorities personally that the president-elect was in danger of being assassinated on his scheduled journey through Baltimore the next day.

In any event, Lincoln, accompanied by Pinkerton and Lamon, passed through Baltimore without being attacked, although there was an odd and long train delay on the station platform. The party arrived in Washington, unannounced, at 6 am, February 23, 1861.

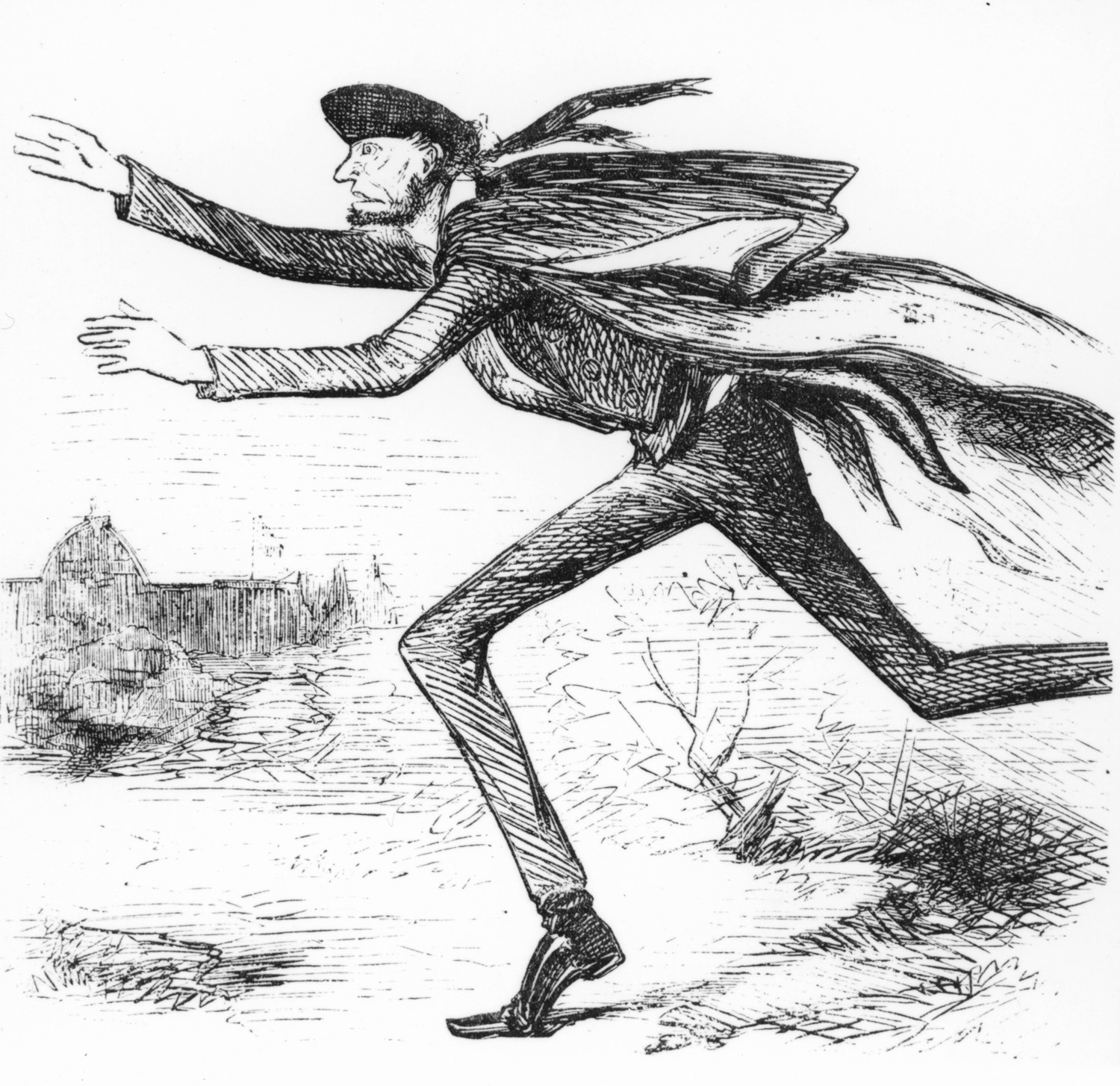

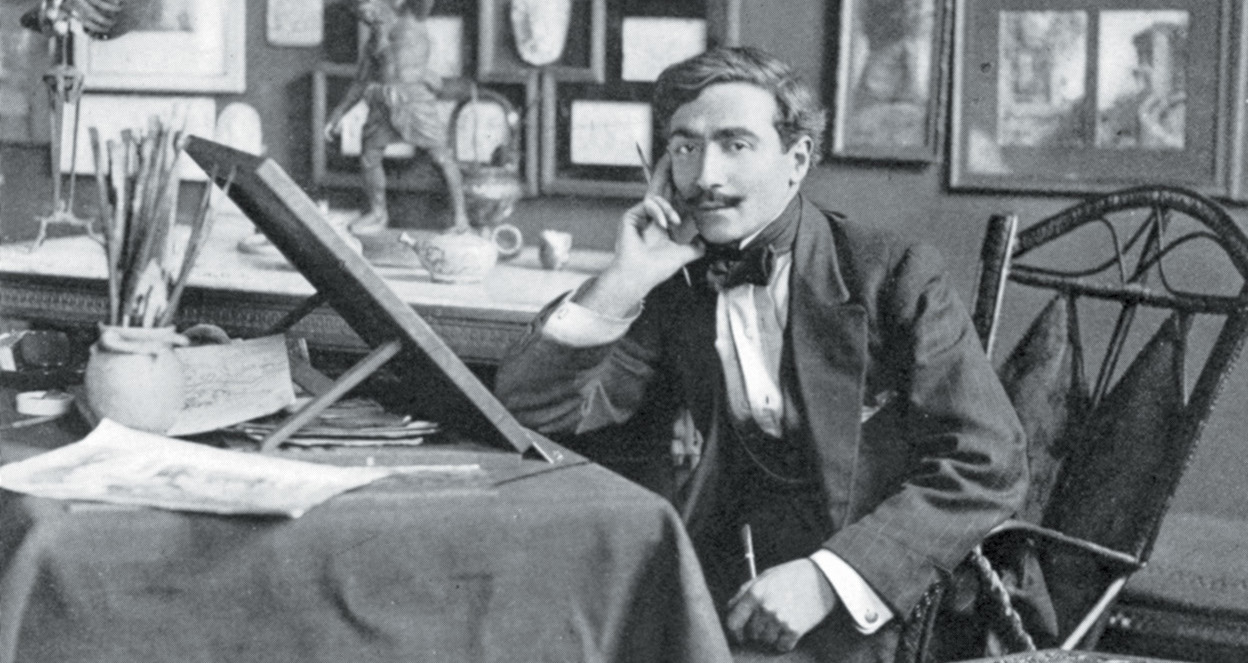

As the story of Lincoln’s secret passage to Washington became known, his political enemies denied the existence of the “Baltimore Plot” and ridiculed him as a coward. Even the president’s friends embarrassed him. A sympathetic newspaper ran the story that caused him the most trouble. New York Times correspondent Joseph Howard, Jr. was one of the reporters left behind in Harrisburg. Howard believed in the reality of the plot but lacked details, so he simply made them up.

He described Lincoln as having arrived in Washington disguised in “a Scotch plaid cap and a very long military cloak, so that he was entirely unrecognizable.” Editorial cartoonists seized on Howard’s description and had a field day mocking the president-elect.

Pinkerton inadvertently added to the ridicule by selecting the word “Nuts” as Lincoln’s codename. Once in Washington, Pinkerton, who was using the code name “Plums,” wired Sanford of the American Telegraph Company, “Plums arrived here with Nuts this morning.”

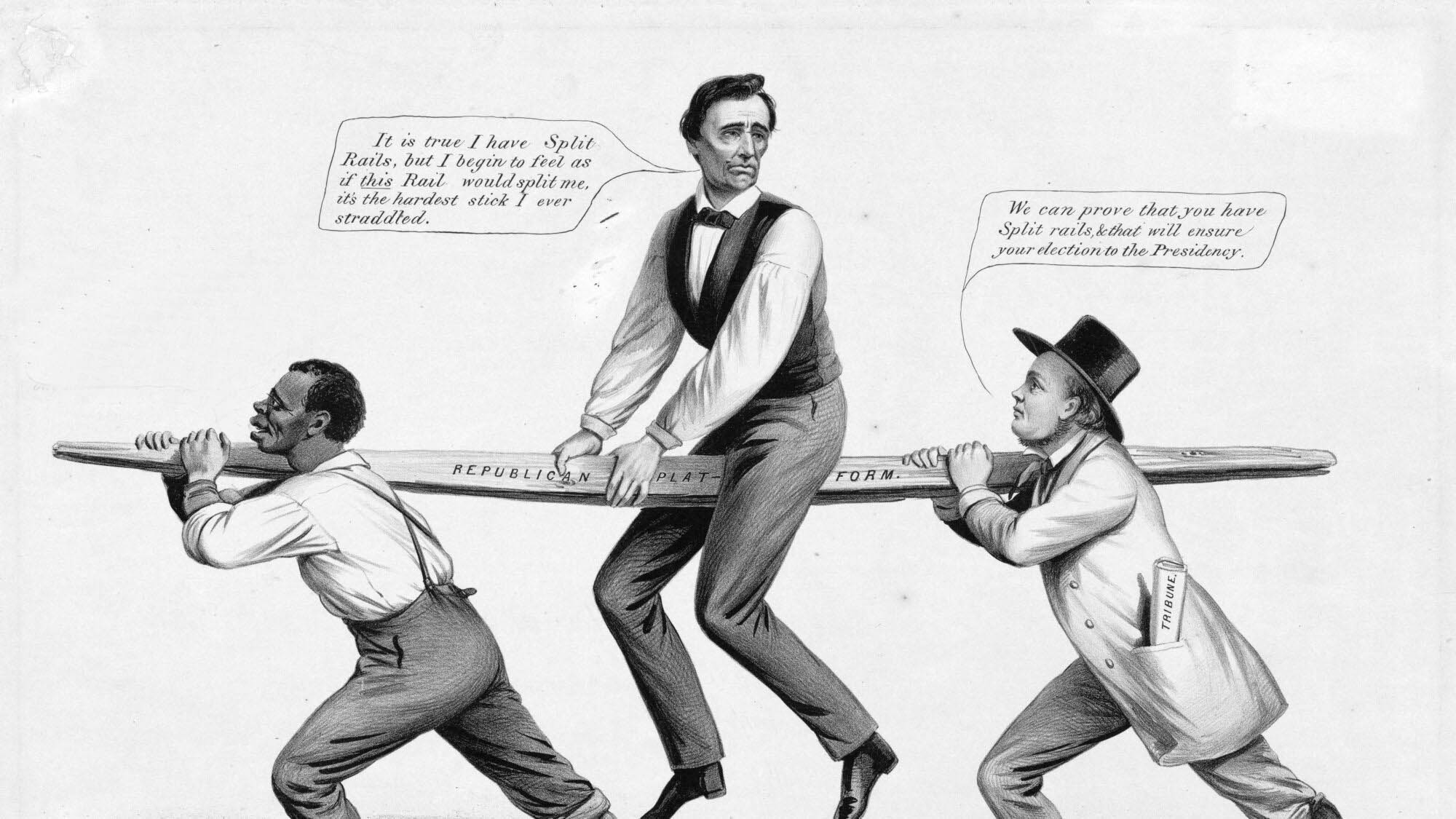

Lincoln had shown great personal courage throughout his life and was also well known for his self-effacing sense of humor. During a political debate an opponent once called him “two-faced.” Lincoln answered, “I leave it to my audience: If I had another face, do you think I’d wear this one?”

The president-elect, however, saw nothing funny about the ridicule. According to his friend Lamon, Lincoln regretted his surreptitious entrance into the nation’s capital and could never again be persuaded to submit himself to such extreme measures to safeguard his life. Thus the media had laid the foundation for his eventual assassination.

Would the assassins’ plan have worked? According to Lincoln, even Pinkerton “did not know that the conspirators would have pluck enough to execute it.” But when the Presidential Special from Harrisburg did arrive in Baltimore as scheduled and with the president-elect supposedly on board (Mary Lincoln was), ten thousand people were gathered, giving terrific cheers for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. And less than two months later, on April 19, Baltimore Secessionists amply showed their resolve by spilling the first blood of the Civil War. They attacked the 6th Massachusetts Regiment and shot down many Bunker Hill Boys as they passed through the Maryland city on their way to the defense of Washington. In the fighting, Secessionists killed three Union soldiers and wounded 39. Twelve Marylanders also died in the fighting.

Would the Baltimore police have looked the other way during the assassination and escape? Marshal Kane continued his Secessionist activities until arrested and incarcerated at Ft. McHenry. He was later discharged and escaped to the South where he was commissioned a general in the Confederate Army.

Was Pinkerton so vital? Since Kennedy’s men also discovered the plot, would not Lincoln have avoided a stop in Baltimore anyway? In 1868, Kennedy wrote to historian Benson Lossing claiming sole credit for detecting the Baltimore Plot and saving Lincoln’s life. Pinkerton, who had remained quiet about his activities throughout the war, then felt obliged to set the record straight. He prepared a detailed and precise booklet containing letters, reports, and affidavits describing his own investigation.

Like Lincoln, Pinkerton was from Illinois. Both men did work for the railroads there and knew each other even before Lincoln’s election. Of their friendship Lincoln said: “Well, I’ve known Pinkerton for years and have known and tested his truthfulness and sagacity.” Still, Lincoln hesitated to change his plans solely on the basis of Pinkerton’s investigation. It seems most unlikely he would have done so on the basis of Kennedy’s investigation alone. It was the independent work of the two men, reaching essentially the same conclusion, that convinced Lincoln to take the precautions necessary to save his life.

A more disturbing question might be this: Was a victory in the Civil War by the North inevitable even under a Hannibal Hamlin presidency? Available manpower favored the North 4 to 1. The North had most of the industry, railroads, resources, and money. Yet large powers have again and again been defeated by small, determined armies. It seems likely that without the genius of Abraham Lincoln the United States would have become disunited.

As the Civil War heated up, Pinkerton wrote the president, offering his assistance. In response, Lincoln summoned him at once to Washington, stating: “[Your] services are, I think, greatly needed by the government at this time.” Pinkerton was made chief of the U.S. Secret Service. He served through 1862 and thereafter was less active around Washington, in sympathy for his friend, General George McClellan, who was sacked in November of that year.

Allan Pinkerton was in New Orleans conducting fraud investigations for the government when word of Lincoln’s assassination reached him. He wrote the War Department offering his assistance. He also observed, “Under providence of God, in February, 1861, I was enabled to save him from the fate he has now met. How I regret that I had not been near to him previous to this fatal act. I might have been the means to arrest it.”

Could Pinkerton have saved the president in April 1865? Allan Pinkerton was the foremost detective of his day. Lincoln’s guard that night was John F. Parker, a notoriously unfit police officer with a drinking problem. Had Pinkerton been on guard at Ford’s Theatre that night, it is unlikely Booth would have reached the president’s box to fire his fatal shot.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments