In World War II, every artillery battalion needed “eyes” to give type-of-target information and coordinates of the enemy in the field. Forward observers, or “FOs,” were with the infantry on the ground in the front lines. The artillery also relied on “flying eyes” in the sky––a group that has historically received little recognition. This is a brief history of one such aerial observation unit during Operation Market-Garden in Holland.

Organization of the 82nd Airborne Division’s Artillery Observers

The flying eyes of the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery, comprising the 376th and 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalions and the 319th and 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalions, had an Air Section made up of ten L-4 Piper Cub spotter planes.

Div Arty’s Air Section consisted of 11 officers; the pilots were assigned two per artillery battalion, together with mechanics and jeep drivers. All pilots, mechanics, and planes were under the direct operational control of Major John T. “Tony” Lala, air officer of the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery.

The AOP (Air Observation Post) pilots assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division for the September 1944 Market-Garden operation were: Lieutenants Albert M. Boulanger and Iler M. Hathaway (376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion); Lieutenants George W. “Dutch” Roberts and John A. Gargilietti (456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion); Lieutenants Wimberly M. Morgan and John H. Miller (319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion); Lieutenants Robert N. Corrigan and Darwin P. Garard (320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion); and Lieutenant Carl Sauer and Captain Lala for Division Artillery Headquarters.

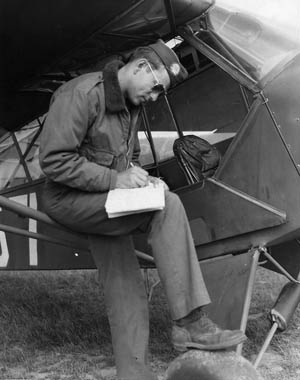

The L-4 Piper Cubs of the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery

The 82nd pilots had picked up their planes at Wantage, England, on July 26, 1944, and each pilot kept his plane for the rest of the war. The men were billeted at a camp outside of Market Harboro and the planes were kept on the Husbands Bosworth airstrip in the same area. Observation training missions were flown from this airstrip each day.

The Piper Cubs used by the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery had the identification number “57” painted on both sides of the fuselage. Essentially a civilian aircraft in olive-drab disguise (instead of the usual Piper Cub yellow), the L-4 was referred to as a “Grasshopper.” An extremely lightweight plane, the L-4 could take off and land on very short runways. Flying slowly over a battlefield, it made a tempting target for the enemy, for opposing forces knew that, shortly after an L-4 appeared overhead, an artillery barrage was sure to follow. The L-4 Piper Cub was of the light monoplane type with high, strut-braced wings and fixed landing gear. The plane had a length of 22 feet, 41/2 inches and a wingspan of 35 feet, 22 inches. When empty its weight was just 680 pounds and it could carry a useful load of 540 pounds, for a gross weight 1,220 pounds.

The L-4 was powered by a J3C-65/L4 Continental A65-8, 65 horsepower air-cooled engine. The fuel tank could hold 12 gallons, which was good for a range of 220 miles. The maximum speed was 87 miles per hour, with a cruising speed of 73 mph, a stall speed of 38 mph, and operational ceiling of 11,500 feet.

The fuselage was a welded steel tubular framework and fabric skin. The plane had two seats: one for the pilot and the other for the observer directly behind him. An SCR-300 FM radio was on board to provide communications with the battalions on the ground. For transport over long distances on water, the little airplane could be broken down and transported in an LCM (Landing Craft, Mechanized, such as was used during the invasion of Normandy in June 1944), or on board an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) as was done during the invasion of Sicily in July 1943.

The first planes that would eventually evolve into the L-4 were built from 1931 to 1938 by Taylor Aircraft Company of Bradford and Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, and its licensees in California, Canada, and Denmark. The company was then taken over by William Piper and renamed Piper Aircraft. From 1938 to 1945, nearly 22,000 of the craft under various model designations (J-2, J-3, J-4, J-5, O-59, L-4, and a training glider TG-8; the L-4 was a derivative of the J-3 and O-59) were built. About 5,375 were built for the Army; the Navy version was designated the NE-1. The Piper J-3 Cub also became the primary trainer aircraft of the CPTP (Civilian Pilot Training Program), from which many military pilots later emerged.

(As an interesting side-note, when the Germans invaded Denmark in 1940, they confiscated a number of planes from the Cub subsidiary there and repainted them in Luftwaffe livery.)

Operation Market-Garden: A Bold Airborne Campaign

After the hard-won success of Operation Overlord, the Normandy Invasion, and the breakout from the beachhead known as Operation Cobra, British and American armies began racing eastward, liberating Paris on August 19 and Brussels on September 3. As the Allies neared Germany’s western borders, however, enemy resistance stiffened. A bold plan was needed if the Allies hoped to reach Berlin and end the war by Christmas, as many planners said was possible.

General Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of British forces on the Continent, was not known for impetuosity; he much preferred the set-piece battle, launching offensive operations only after careful preparation. Criticized by the top brass for taking a month to capture Caen, his plan for Market-Garden was therefore quite a departure for the usually cautious, methodical Monty.

Market-Garden was conceived because, by the fall of 1944, the Allies had come up against the fixed fortifications of the West Wall and the Allies’ supply situation was becoming critical. So, instead of continuing to advance on a broad front, which had become difficult to supply from the few ports controlled by the Allies, Montgomery believed that a powerful, rapier-like thrust through one point of the German lines would be more effective.

As the official U.S. Army record of the operation says, “Three and a half airborne divisions were to drop in the vicinity of Grave, Nijmegen, and Arnhem to seize bridges over several canals and the Maas, Waal (Rhine), and Neder Rijn Rivers. They were to open a corridor more than 50 miles long leading from Eindhoven northward.”

Market-Garden, therefore, would begin with a lightning stroke of 30,000 British and American paratroopers and glider forces being dropped in an “airborne carpet” behind enemy lines near the Dutch towns of Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem––along the Dutch/German border in what was thought to be a lightly held enemy sector.

Simultaneously, the tanks and infantry of British General Brian Horrocks’s XXX Corps were to drive up a narrow highway (soon to be known as “Hell’s Highway”) leading from the Allied front lines to eight key bridges, relieve the airborne troops, and then cross the bridges before the retreating Germans could destroy them.

However, shortly before the operation kicked off, aerial photos revealed the presence of two SS Panzer divisions (the 9th and 10th) near Arnhem––troops that would not easily be intimidated in the event of an Allied assault. Despite this worrying discovery, Monty made the decision to go ahead with the operation.

Objectives of the Airborne

The Allies’ airborne forces were formidable. Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor’s 101st U.S. Airborne Division, flying in from England, would drop farthest south, between Eindhoven and Veghel, securing 15 miles of the corridor, the city of Eindhoven, and the bridges at Zon, St. Oedenrode, and Veghel.

The 82nd U.S. Airborne Division, also arriving from England and under the command of Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, would land north of the 101st and capture the bridges over the Maas at the ominously named town of Grave, the Waal at Nijmegen, the Maas-Waal Canal between the two cities, and a hill mass southeast of Nijmegen.

The 1st British Airborne Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Roy C. Urquhart, would land the farthest from Allied lines—at Arnhem—to secure the Neder Rijn Bridge. The 1st Polish Parachute Brigade, under Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Sosabowski, would drop on D plus 2 to reinforce the British there. Enemy anti-aircraft defenses near Arnhem were thought to be too extensive to land gliders near the town, so plans were changed to land the glider-borne troops at a site seven miles away, thereby losing any element of surprise.

Although it would have been preferable to land the airborne and glider forces all on the same day, practical considerations changed that concept. While the airborne division commanders requested that the transport aircraft fly more than one mission per day, the troop carrier commanders said that flying more than one mission per plane would jeopardize the entire operation, giving them less time to perform spot maintenance, repair battle damage, and rest the air crews. Lt. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, head of the First Allied Airborne Army, sided with the troop carrier commanders and there the matter rested.

Operation Market-Garden Under Way

As D-day for Market-Garden, September 17, 1944, approached, the pilots and aerial observers of the 82nd Airborne Division, encamped at the Husbands Bosworth airstrip, prepared for their mission. On Saturday, September 16, Lieutenant Albert Boulanger (in L-4 # 57-A) and Lieutenant Iler Hathaway (in # 57-B) flew to London, with each plane carrying two extra five-gallon cans. Other pilots, along with thousands of paratroops, glider troops, and escorting fighters, also began gathering at 24 airfields from which the massive operation would be launched.

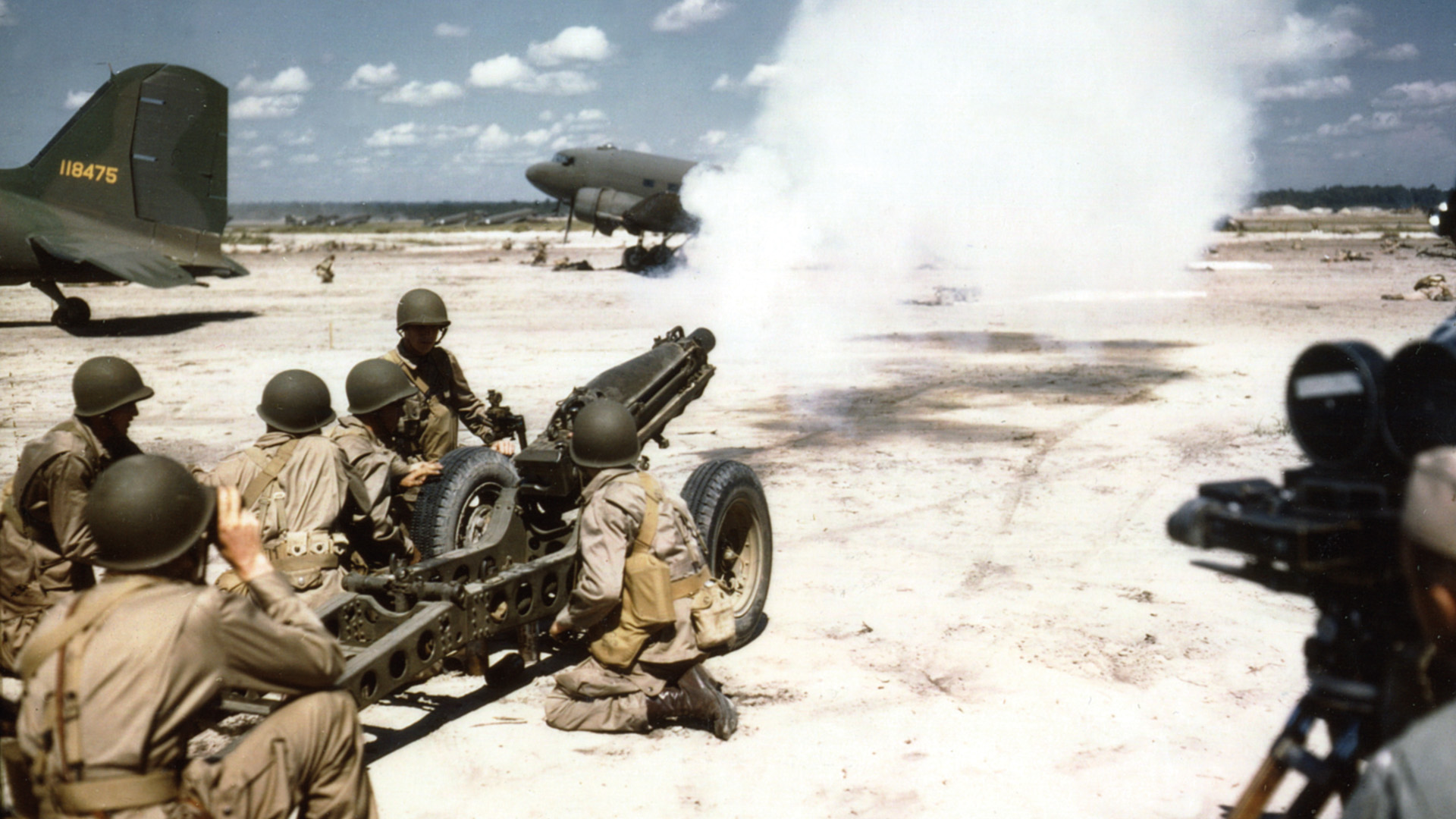

On Sunday, September 17—a beautiful, warm, cloudless day—the operation commenced when 500 gliders and 1,500 aircraft carrying airborne troops, under the command of Lt. Gen. Frederick A.M. “Boy” Browning, who had had just seven days to prepare for the operation, flew above the men of XXX Corps, which would follow in their tanks and trucks. Allied guns supported the operation with a huge barrage designed to knock out German resistance along the highway.

Soon after the start of the operation, things began to go wrong. As the XXX corps tanks rolled down the highway, German gunners knocked out the first nine vehicles, bringing the advance to a halt for 40 minutes. The British paratroopers, advancing toward Arnhem, also came under attack. Then they discovered that their radios didn’t work properly, making it impossible to coordinate the assault.

One British battalion did manage to penetrate the German perimeter around Arnhem and, by 8:00 PM that evening, the battalion had captured the northern end of the road bridge across the Rhine; the Americans at Grave had also reached their objectives. But the Germans, now on full alert, had blown up most of the bridges before they could be captured.

By the end of the first day, XXX Corps had advanced only seven miles from their start line and had failed reached their first bridge. Meanwhile, the Germans were bringing up reinforcements and their panzers were moving into Arnhem.

Late Arrival of the 82nd Division Artillery

Through no fault of their own, the aerial spotters and pilots of the 82nd Division Artillery were late getting to the battle. On the night of September 16/17, they were still at an airstrip near London. From there, the L-4s left in two groups for Holland to prepare to become the aerial eyes of the 82nd Airborne Division. The first group of five planes, commanded by Lieutenant Robert Corrigan, left London on the 17th and crossed the Channel at low level, flew straight to Dieppe, France, and landed in a farmer’s field near St. Vailery, south of Dieppe. The other pilots in the group were Captain Lala and Lieutenants Gargilietti, Morgan, and Hathaway. The second flight, under command of Lieutenant Roberts, would not leave the London area until three days later.

Corrigan’s men stayed at St. Vailery overnight and the following morning they refueled from the five-gallon cans. A number of stops were made along the way to the front, for the maximum time in the air was a little over two hours. Most of the way was flown in a straight-line formation.

Attack Across the River Waal

On September 18, the second day of the battle, rumors circulated amongst the 82nd officers that German infantry, and perhaps even some armor was congregating in the Reichswald forest near Nijmegen, but the rumors were unconfirmed. Nevertheless, Gavin requested that the British 2nd Tactical Air Force strafe the area, followed by harassing fire from the 82nd’s Div Arty.

Also on the 18th, XXX Corps finally began to make progress. Horrocks’ tanks covered 20 miles in a few hours, joining up with the 82nd Airborne at the intact Maas bridge near Grave. On the third day, XXX Corps reached Nijmegen, where the American paratroopers were still fighting in the streets in their efforts to reach their objective: the bridge across the mighty River Waal.

After conferring with Gavin, General Horrocks ordered the Americans to attack in canvas assault boats across the River Waal and take the German-held end of the bridge. The attack was enormously costly. Half of a company of the 82nd Airborne Division was either killed or wounded on the crossing. The survivors reached the far bank, and from there stormed the bridge and captured it.

Once the bridge at Nijmegen was secure, XXX Corps only needed to push on to Arnhem, where the British paras were still clinging to the north end of the bridge. It seemed that Operation Market-Garden, despite the odds against it, might actually succeed.

At last, Hell’s Highway—the route to Arnhem—was in Allied hands. However, it was too late for the British parachute battalion at the north end of the Arnhem bridge. The Germans had moved their tanks into the town and were systematically shrinking the British perimeter by demolishing the houses from which the paras were fighting.

By now, Lt. Col. John Frost and his men were short of anti-tank weapons, food, and ammunition. The survivors would be forced to surrender on September 21 before help could arrive.

Arrival of the Piper Cubs

The 82nd Airborne artillery’s pilots headed for Brussels and were to continue on to the Nijmegen area but, due to deteriorating weather conditions, the L-4s did not leave Brussels until the morning of Wednesday, September 20. From Brussels the pilots took off for Bourg Leopold and landed on a British AOP field. The first group of five L-4s flew over a corridor to Eindhoven and Grave and arrived in the 82nd Airborne Division’s operational area on September 21st. Since the corridor was only about a mile wide, the pilots flew over the only highway leading north from Eindhoven to Nijmegen––a highway loaded with British convoys. Then as now, the highway was lined with trees most of the way, so the pilots flew low to avoid detection, with the fuselage between the branches and the wings out over the treetops, each pilot carefully looking out for electric and telephone wires.

The pilots were only armed with carbines or .45 caliber pistols, tucked under their seats. The L-4s did not have self-sealing gas tanks and a well-placed tracer bullet could have turned the airplanes into flaming fireballs. The ground crews (mechanics, mechanic’s helpers, and jeep drivers) of the 376th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, plus a half-ton truck with a gasoline trailer, arrived in the operational area in a convoy. Some of the jeeps had a .50 caliber machine gun mounted.

Upon flying over Heumen, the road, which was to be used as a landing strip, was occupied by British vehicles, so the pilots had to land their tiny airplanes in a field beside the road. There was a quick briefing from Captain Lala and other officers on the enemy situation and, at 4:20 PM, Lieutenant Corrigan reported to Division Artillery Command

Post, where Colonel Francis A. March, the Div Arty commander, ordered Corrigan to bring the pilots and airplanes to a field at Malden the following morning. Due to fog, however, the spotter planes did not arrive until later in the day.

Spotter Aircraft on Patrol

Meanwhile, each artillery battalion was ordered to organize a ground observation post for the purpose of alerting the unarmed Air OPs upon the approach of hostile airplanes. The ground OPs had a definite zone of responsibility: the 319th Field Artillery Battalion from the north to the east, the 320th from the west to the north, the 376th from the south to the west, and the 456th from the east to the south. When enemy planes were sighted, an L-4 was to be alerted by radio. Direction and number of the enemy planes were given to the pilots and observers.

Generally, the flight path on a normal patrol was flown at altitudes of 400 to 1,400 feet, slightly on the 82nd’s side of the front lines, and covered the division’s front. The pilots and observers were to search out strongpoints, troop movements, and hidden gun emplacements.

When anything suspicious was spotted on the ground, the men flew beyond the front lines to take a closer look, call down fire commands, observe the results, and make any necessary adjustments.

A write-up of the day said, “The artillery Air OPs arriving on D plus 3, have been a thorn in the side of German operations since their arrival, cracking down accurate fire on mortars, Nebelwerfers, or batteries as they appear. With two of their Cubs attacked by German fighters, the air pilots and observers jauntily continued their flights as if there was no opposition, keeping Jerry under cover throughout the day.”

A 500-yard-long airstrip for the L-4s was established next to the railroad track at the D’Almarasweg at Nijmegen, easily seen from the air because there was a wrecked passenger train with the engine shot out in the bend of the track. (This train had been stopped by a bazooka from F Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment several days earlier at Groesbeek. The engine was rolled back to Nijmegen.) There were some trees at one end of the strip under which L-4s were parked and concealed. (In a later stage of the operation, engineers bulldozed down some of the trees. A Canadian anti-aircraft unit set up their guns several hundred yards from the airstrip to give it some protection against Luftwaffe air raids.)

One of the first things the pilots did when they arrived in the area was locate all the church steeples and tall chimneys of the brick kilns northeast of Nijmegen, as the Germans used these steeples and chimneys as observation posts. The L-4s’ presence in the sky over the embattled troopers of the 82nd fighting in the streets of Nijmegen must have given the sky soldiers the comforting sense that they had not been abandoned. In the later stages of Market-Garden, however, inclement weather made it impossible to fly all day long.

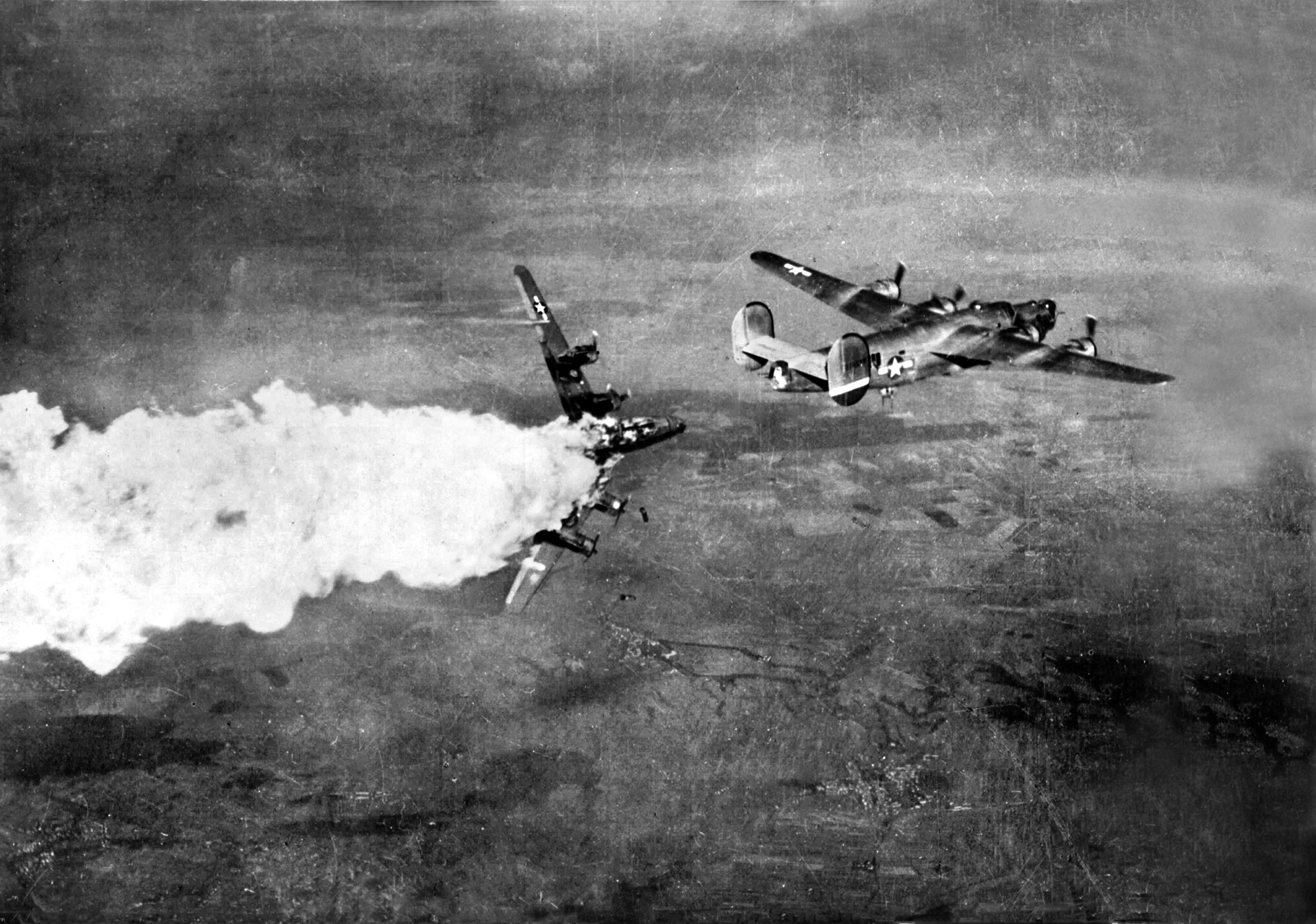

Encounters with Me-109s

With the collapse of the British holdouts in Arnhem, Operation Market-Garden officially ended on September 25 as one of the worst defeats suffered by the western Allies in the entire war. Some 15,000-17,000 casualties (dead, wounded, missing) were suffered by the Allies during the nine-day battle; the Germans lost 7,500-10,000 men.

The end of the battle, however, did not mean an end to all the fighting, nor to the 82nd Air Ops’ role.

After returning from a mission over enemy lines on September 26, Lieutenant John Gargilietti of the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion was attacked by four Messerschmitt Me-109s. Gargilietti began twisting and turning over the trees to avoid the stream of bullets being sprayed toward his plane, but the small, unarmed aircraft was shot down at the end of the airstrip on its final approach and crashed into a pine tree grove. Luckily, the trees broke the fall of the plane, but the nose of the L-4 was buried about three feet into the ground; the Cub was a complete loss. Lieutenant Gargilietti and his observer, Lieutenant Aiken, were both injured and taken to one of the hospitals in Nijmegen. It was the kind of hazardous duty that all Air OPs faced.

Sometimes the Air OPs corrected intelligence gathered on the ground. On the afternoon of September 27, Dutch civilians reported a column of 50 panzers heading for Zyfflich, just across the Dutch-German border, in the direction of the front lines of the 82nd’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Lieutenant Hathaway and his observer (L-4 #57-B) were ordered to search for the reported tanks and supporting infantry. The men spotted the enemy (but only five tanks), flew back, landed, and reported to Colonel John W. Smiley, the Division Artillery S-3. The U.S. Air Force was contacted and fighters were dispatched to neutralize the threat by about 4:00 PM.

Throughout the autumn, the 82nd’s Air OPs flew missions over German positions almost every day and reported enemy movements or positions of targets to the artillery battalions––and put their lives on the line each day, either from ground fire or fighter attack.

For example, on October 21, three Messerschmitt Me-109s attacked the L-4 Piper Cub flown by Lieutenant Darwin P. Garard of the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion. Garard’s plane was hit but not disabled, and the infantry shot down one of the Messerschmitts; the German pilot was unable to leave his burning fighter and was killed in the crash.

“When the Cub Flies Over, All Things Cease”

During Market-Garden, Lieutenant Albert Boulanger flew 27 firing missions and 25 patrols; Lieutenant Hathaway flew 50 missions during the same period. In mid-November, with solid overcast covering the skies over Holland, all the 82nd’s Air Ops were ordered back to Suippes, France, where the men set up an airstrip and started to train new observers for the forthcoming springtime operations.

For their devotion to duty, in early 1945 First Lieutenants Hathaway, Boulanger, and Walsworth were awarded the Air Medal.

Perhaps the greatest praise for their service came from a German prisoner of war: “When the Cub flies over, all things cease. All we move are our eyeballs.” The reason: The Germans knew by experience that when the L-4 Piper Cubs were spotted, Allied artillery fire would follow on their positions.

My father, David Arnsan, was in Army Intelligence in the European Theatre. His military records were destroyed in that devastating fire and I have searched in vain for more information about him. He died in 1981. I wish I had asked him more questions.

He told me that because he was color blind, he could determine real foliage from camouflage and had been an observer in a piper cub at one point. I remember seeing photos of a bombed out German city that he took, so I think that he was with some of the early units to enter Germany.

It would be greatly appreciated if anyone knows anything about Tech Sergeant, David L. Arnsan ( might have been spelled Arnson).

Another W.H.N. fail. Misidentified aircraft. The “Houston Hunch II” is a Stinson L-5. No references or citations given. No photo credits given. History without documantation is paramount to mythology. Please do better and show some professionalism. .

This story, like most on our website, was published in one of our (print) magazines. Generally, the images in the magazines include photo credits, when available, and the captions typically reference the information included with the original images, likely written during WWII. Many come from official records contained at the National Archives and Records Administration, and other government agencies. If you are looking for images with credits perhaps you would like to check out the print versions of these stories.

I agree with Rory Brown. Good captions and credits are to be expected, and I don’t see why they can’t be brought over from the print magazine. We have, I hope, moved on from the times when every knocked out German “Tiger Tank” pictured was a Pz IV when you looked closely and similar gaffes.

I must agree with Mr Brown and Mr. Jackson: if these were brought over from the print edition — and I am grateful to read on line — there are editing errors and credit omissions hat should have been caught before the print editions went to press.

I appreciate the response from Mr. Gnam; I’ve sent in similar complaints to the above and saw no response.

As a former photojournalist (TIME, NEWSWEEK, NYT, FORBES, et al.), I was expected to provide correct and useful captions and worked hard at providing those when we all were still shooting film and never saw our images until published.

Houston Hunch II is clearly a Stinson L-5, not a Piper L-4. That being said, are there any other photos of Houston Hunch II that I could use for documentation for painting up a model?

Good comments from all about a good article and its seldom-covered subject. Years ago I got to fly in an L-2 (actually piloting it for a while – what fun!) and an L-4, at an airshow in, of course, Lockhaven, PA! Both had the correct O.D. paint on, with the L-4 having invasion stripes and possible reference to the 82nd A/B. It’s been decades so my memory about the markings are fuzzy. Anyway, The pilot and I strapped ourselves in and, flying with the door open (the top half hooked to underneath the overhead wing and the bottom half just hanging open – nothing between me and terra firma but my seatstraps!) I got an amazing ride, so slow and low that I could see everything on the ground easily. I thanked the pilot a number of times for giving me a free ride in a great genuine WW2 aircraft. Getting rides like that at a smaller airshow – what an experience!