By Victor Kamenir

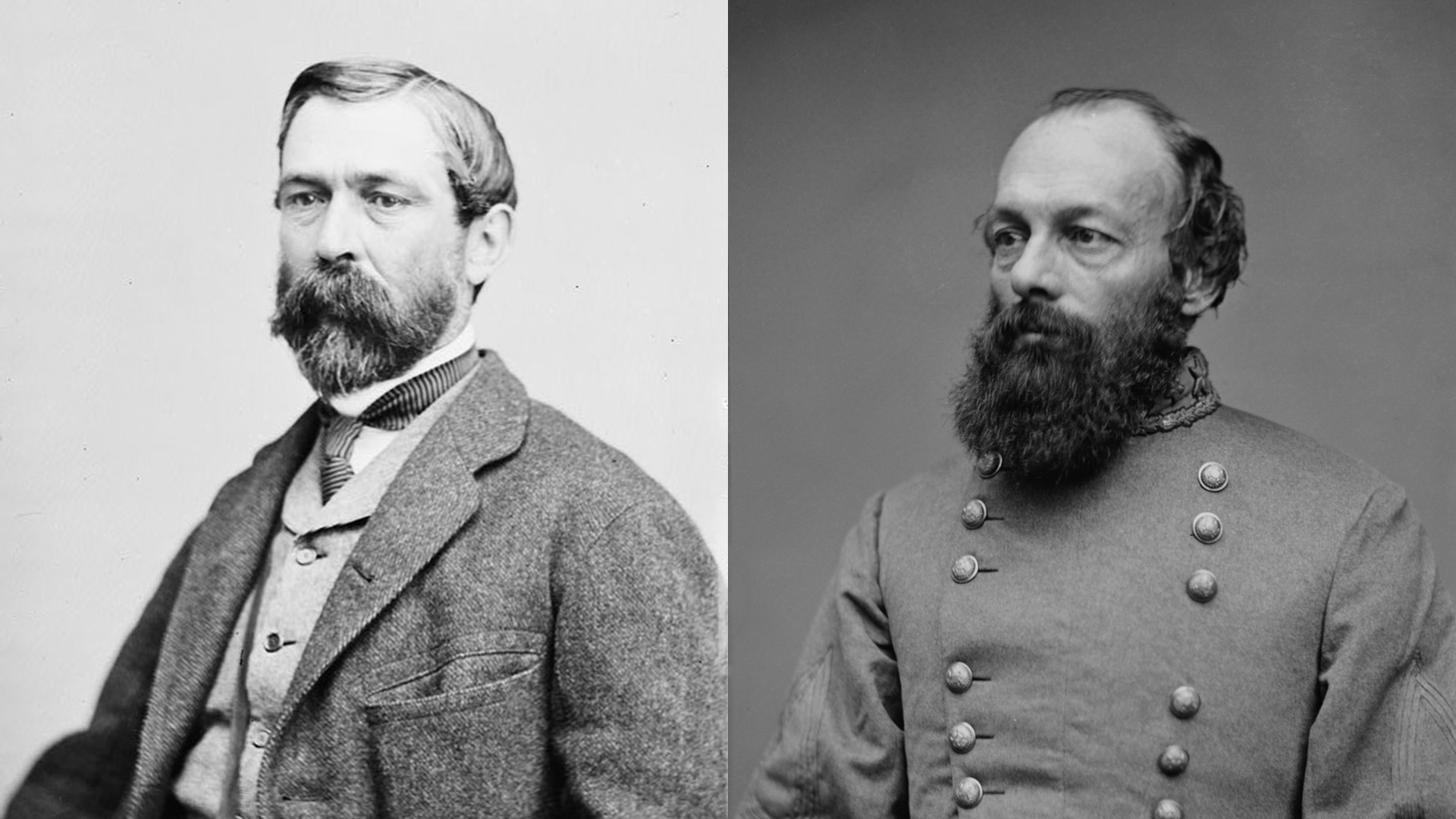

French Admiral Pierre-Andre de Suffren de Saint Tropez did not fit the image of a dashing naval officer. Although a scion of one of the noblest houses of Provence, Suffren looked more like a disheveled clerk of some second-rate counting house. The obese admiral, whose rumpled clothes were frequently spotted with food stains, lacked social graces and liberally sprinkled his speech with language more appropriate in the saloons frequented by sailors than the refined salons inhabited by aristocrats. The ungentlemanly Suffren had two overreaching loves. One was a gluttonous obsession with food, and the other was an unquenched thirst for fighting the British.

Like many other noble youths from the maritime Provence region, young Pierre-André joined the French Navy as a naval cadet in October 1743 at the age of 14. His classroom training did not last long and four months later young Suffren reported for duty on the 64-gun ship-of-the-line Solide when hostilities with Great Britain flared up during the War of the Austrian Succession. Suffren was captured in 1747 on board the Monarque during the Second Battle of Cape Finisterre. Rear Admiral Sir Edward Hawke commanding a British squadron successfully enveloped the rear of a larger French squadron and captured six ships in the hard-fought naval action. Suffren had the opportunity to observe Hawke’s success firsthand and took careful note of it. The humiliating experience of captivity and perceived British heavy handedness instilled lifelong animosity toward the British in Suffren during his formative years.

Repatriated after the war, Suffren went to the island of Malta, where his family had been prominent in the Order of Malta for several generations. The order’s small efficient navy plied the waters of the Mediterranean protecting European shipping from the North African Barbary pirates.

Suffren returned to the French Navy in 1753 during the Seven Years’ War. On August 19, 1759, the young lieutenant participated in the Battle of Lagos, which was fought off Portugal’s southern coast. During this famous naval clash he served under Admiral Jean-François de la Clue on the admiral’s flagship Ocean. When the French fleet was dispersed during the battle, four French ships took shelter in Lagos Bay, which was neutral Portuguese territory. Disregarding international law, British Admiral Sir Edward Boscawen attacked the French ships in the bay, destroying two of them and capturing the other two. Suffren became a British prisoner once again. He would remember vividly how Boscawen flagrantly violated international law and would employ that tactic himself more than two decades later. Repatriated once again at the end of the war, Suffren alternated serving in the navies of France and Malta, eventually commanding two xebecs (three-masted vessels with both lateen and square sails), two frigates, and a Maltese galley.

From the low point at the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, France launched an ambitious program to rebuild her navy to challenge British supremacy. Naval budgets increased significantly to restart shipbuilding, and improvements were made in administration, procurement, and recruitment.

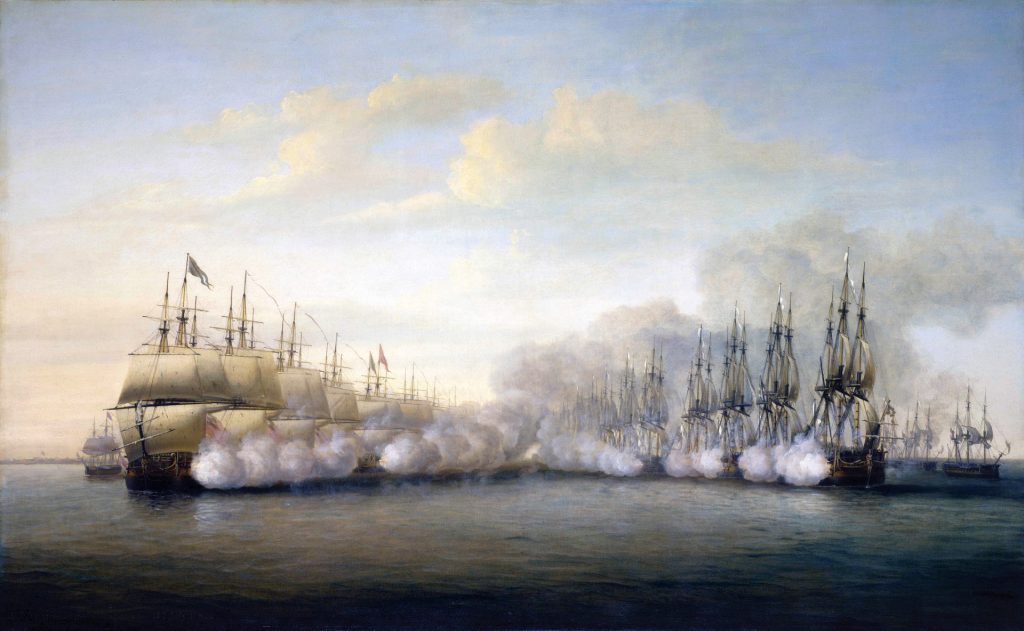

Both the French and British navies adhered to the strict doctrine of the line of battle, even though the British allowed far greater initiative to their captains. Naval warfare in the Age of Sail, which naval historians state began in 1571 and ended in 1862, was characterized by opposing fleets drawn up in lines dominated by large battleships called ships-of-the-line, while smaller combat vessels, frigates, and corvettes were largely tasked with scouting, communications, and convoy escort.

Because the cannons were mounted on two sides of the ships in equal number, only a few cannons could be mounted on bow and stern. This made ships vulnerable to a volley fired from directly in front or behind, called raking. The best protection against raking fire was to have ships sail close to each other in a straight line to prevent enemy penetration. A way to defeat the line of battle was for a line of warships to cross in front of a line of enemy ships, a tactic known as crossing the T. This allowed the crossing line to bring all its guns to bear while receiving fire from only the forward guns of the enemy ships. Another tactic was to sail one’s ships on both sides of the enemy in order to bring fire to bear on both sides of the enemy’s ships.

These tactics involved considerable skill in ship handling and required a high degree of cooperation and coordination between individual captains. Each side performed an intricate naval choreography in an attempt to gain the advantage of the weather gage, a position upwind of the opposing vessel. The upwind vessel enjoyed the ability to maneuver, to bring both starboard and port guns to bear on the enemy, while the downwind vessel was forced to make series of zigzag tacking moves as it struggled to sail indirectly against the wind.

The American War of Independence gave France the chance to regain territory lost to the British. Starting with clandestine material aid to American rebels, France entered into a formal alliance with the newly created United States of America on February 6, 1778, and declared war on the Great Britain the next month. With Spain and the Netherlands entering the war on the French side in 1779 and 1780, respectively, the conflict took on the nature of a global war, from North America to the East Indies.

Suffren rejoined the French Navy with the rank of capitaine de vaisseau, the equivalent of a full colonel, and commanded the 64-gun Fantastique in Charles Hector d’Estaing’s squadron off the coast of North America and the West Indies in 1778-1779. Throughout the desultory campaign, Suffren always aggressively sought action, earning the respect of d’Estaing who, upon return to France, recommended Suffren to King Louis XVI for promotion for his zeal and courage. Yet with 39 noble officers of the same rank and more seniority in grade, promotion was out of the question and the king instead awarded Suffren with an annual pension of 15,000 livres. An opportunity for an independent command came in early 1781.

In late 1780, French agents in England reported that a British squadron under Commodore George Johnstone was being prepared to sail for the East Indies to reinforce the British squadron already there. Since the Netherlands entered the war on the side of France in December 1780, the Dutch Cape Town colony would be a likely target for Johnston on his way to the East Indies. Located at the southern tip of Africa, the colony was the gateway to the Ile-de-France (modern-day Mauritius), the main French base in the Indian Ocean.

To prevent the strategic colony from falling into British hands, in March 1781 Suffren was placed in charge of a five-ship squadron escorting a troop convoy to Cape Town. Upon reinforcing the colony, Suffren was to be promoted to the next rank of chef d’escadre and merge with the French Indian Ocean squadron under Thomas d’Orves. Governor of Ile-de-France François de Souillac was in overall command of French forces east of Africa.

On March 22, 1781, Suffren’s squadron, consisting of five ships of the line, three frigates, and one corvette and escorting transports carrying 1,200 army troops, sailed from Brest. The battleships in Suffren’s squadron were the Heros and Annibal, mounting 74 guns each, and the 64-gun Artecien, Sphinx, and Vengeur. Several days later, a fast corvette raced for the Cape Colony to advise the Dutch authorities about the Dutch entry into the war and the French relief force being sent. Shortly before Suffren’s departure, the French learned that Johnstone was already on the way to the East Indies, and Suffren knew he was in for a race if he was to beat Johnstone to the Cape Colony.

Artecien was a late addition to the squadron. Initially being prepared for a shorter run to North America, the vessel quickly began to run out of fresh water. To take on more drinking water and make some repairs, Suffren diverted to the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands, a small archipelago off the west coast of Africa. On the morning of April 16, 1781, Artecien, sailing ahead of the French squadron, stumbled upon Johnstone’s British squadron anchored in Porto Praya Bay.

Remembering Admiral Edward Boscawen’s blatant violation of Portuguese neutrality 22 years earlier at Lagos, Suffren made a snap decision to destroy Johnstone’s squadron. Correctly surmising that Johnstone would not be expecting trouble in a neutral Portuguese port, at 0900 Suffren ordered his squadron to close up for an attack. At mid-morning with Sphinx and Vengeur still far to the rear, Suffren entered the bay with his other three ships-of-the-line, the British completely by surprise. Not only were 1,500 British sailors relaxing on the beach, but Johnstone’s five ships-of-the-line and three frigates lay at anchor intermixed with dozens of merchant ships and troop transports.

As Suffren in Heros sailed along the clustered British ships, British soldiers aboard the transports armed with muskets poured a heavy fire into the French vessels. Captain Alexandre de Tremigon, commanding Annibal, did not believe until the very last moment that a battle would take place in a neutral port and did not make his ship ready for action in time. Nonetheless, Tremigon skillfully maneuvered his ship to a position next to Heros. While his sailors rushed to clear the decks for action, Annibal was subjected to British fire without being able to reply in kind. When the next ship in line, Artecien, was entering the fray her captain Chevalier de Cardaillac, was struck in the head and killed by a musket ball.

Artesien’s second in command, knowing Cardaillac’s intentions of capturing a British ship, briefly boarded a merchant ship that eventually drifted out of the harbor. The last two French ships, Vengeur and Sphinx, arrived at last around 11 am. Because they encountered an increasing headwind and were carried out of the harbor, they were able to exchange only a few desultory broadsides with the British.

Heros and Annibal were left alone to bear the brunt of intensifying British fire. The two French ships furiously fought back, with Heros damaging a mast on Monmouth. Annibal suffered extensive damage, losing two masts, and Captain Tremigon’s leg was carried away by a cannon ball. The halyard rope holding her flag was cut, sending the flag fluttering into the sea. The British cheered in the mistaken belief that Annibal was surrendering. But her second in command, Lieutenant Morard de Galles, ordered a large napkin brought up from the wardroom and nailed it to the remaining mast, signaling that Annibal was still in the fight. His surprise attack having turned into a trap, Suffren ordered a retreat at noon. As Annibal followed Heros out of the bay, she lost her third mast and had to be taken in tow by the Sphinx.

French losses during the Battle of Porto Praya were 242 wounded and 107 dead, including Captain de Cardaillac of the Artesien and Captain Tremigon of Annibal, who succumbed to his mortal wound. As Suffren slowly made his way to the Cape Colony, with Annibal being alternatively towed by Heros and Sphinx, he fumed at the poor performance of his captains and the missed opportunity of defeating an enemy squadron. Not the least of Suffren’s worries were the political ramifications of his violating Portuguese neutrality and he dispatched a frigate to France with a letter articulating in great detail the necessity of his actions in preventing the British from reaching the Cape first.

Despite suffering relatively minor casualties, 36 dead and 130 wounded, and only one ship seriously damaged, Commodore Johnstone inexplicably remained at Porto Praya for another two weeks, giving Suffren the strategic victory of beating the British to the Cape Colony. The action at Porto Praya was bitter evidence for Suffren that he could not expect his captains, steeped in the rigid tradition of the line of battle, to instantly react to a fluid situation.

On June 21, after 64 days sailing from Porto Praya and 92 from Brest, Suffren’s squadron arrived at the Cape Colony in severe need of repairs and rest. Commodore Johnstone’s British squadron arrived at the Cape in mid-July, but Suffren, with his ships slowly undergoing repairs, did not sally from the sheltered harbor to engage him. After sweeping up five Dutch merchant ships as prizes, Johnstone dispatched three ships-of-the-line to reinforce the British squadron in the Indian Ocean and sailed back to England with the rest.

After two months at the Cape, Suffren’s ships and crews were in adequate condition to continue the journey. Leaving 500 French soldiers to bolster Cape Colony’s defenses, Suffren’s squadron arrived at the Ile-de-France on October 25, 1781. When in October 1778, the British captured Pondicherry, the main French outpost in India, the small French naval squadron under François de Tronjoly fled to Ile-de-France after a brief clash with the British. Tronjoly, wounded during the clash, turned the squadron over to his second in command, Thomas d’Orves, himself suffering from rapidly declining health.

In January 1781, d’Orves put in a half-hearted appearance off India’s southeastern Caramandel Coast, but turned back to Ile-de-France without taking any action against the British squadron under Rear Admiral Sir Edward Hughes. Furthermore, d’Orves neglected to make contact with France’s only Indian ally, Hyder Ali, the Nawab of Sera and Mysore, who was expecting French coordination with his land campaign against the British. Sapped of strength and energy by his illness, d’Orves was easily swayed by the captains in his squadron toward easy sedentary living at the Île-de-France.

Suffren quickly became bored by the comfortable life of the Ile-de-France’s squadron. “The military spirit has been forgotten, but what can you expect from the indulgence and insubordination of their subalterns, who look on this place as their patrimony and do what they like by making their senior officers afraid of them?” he wrote to a friend. “Nearly everyone has a wife or a regular mistress. The ladies are charming, life is comfortable. Many have made their fortunes and become proud and factious.”

Suffren and d’Orves were of the same rank, but the latter had longer time-in-service and Suffren grudgingly acknowledged d’Orves’ seniority over the combined squadron by then numbering 11 ships-of-the-line, three frigates, and four corvettes. Yet a conflict quickly arose between Suffren and the cabal of d’Orves’ captains, when, upon their demands, d’Orves gave command of Annibal to one of his inner circle, Captain Bernard Tromelin. The mutual enmity deepened as time went by, fueled in no small part by Suffren’s ungentlemanly manners and appearance, as well as his unconcealed disdain for the Ile-de-France captains, and largely undermined everything Suffren hoped to accomplish.

On December 7, 1781, after completing repairs to Suffren’s ships, d’Orves’ squadron departed for India, escorting 10 troop transports carrying 3,000 troops which Governor Souillac added on his own initiative to assist Hyder Ali. The crews of the French ships were supplemented by East Indian sailors and 500 black slaves who were offered the choice of naval service as free men or death.

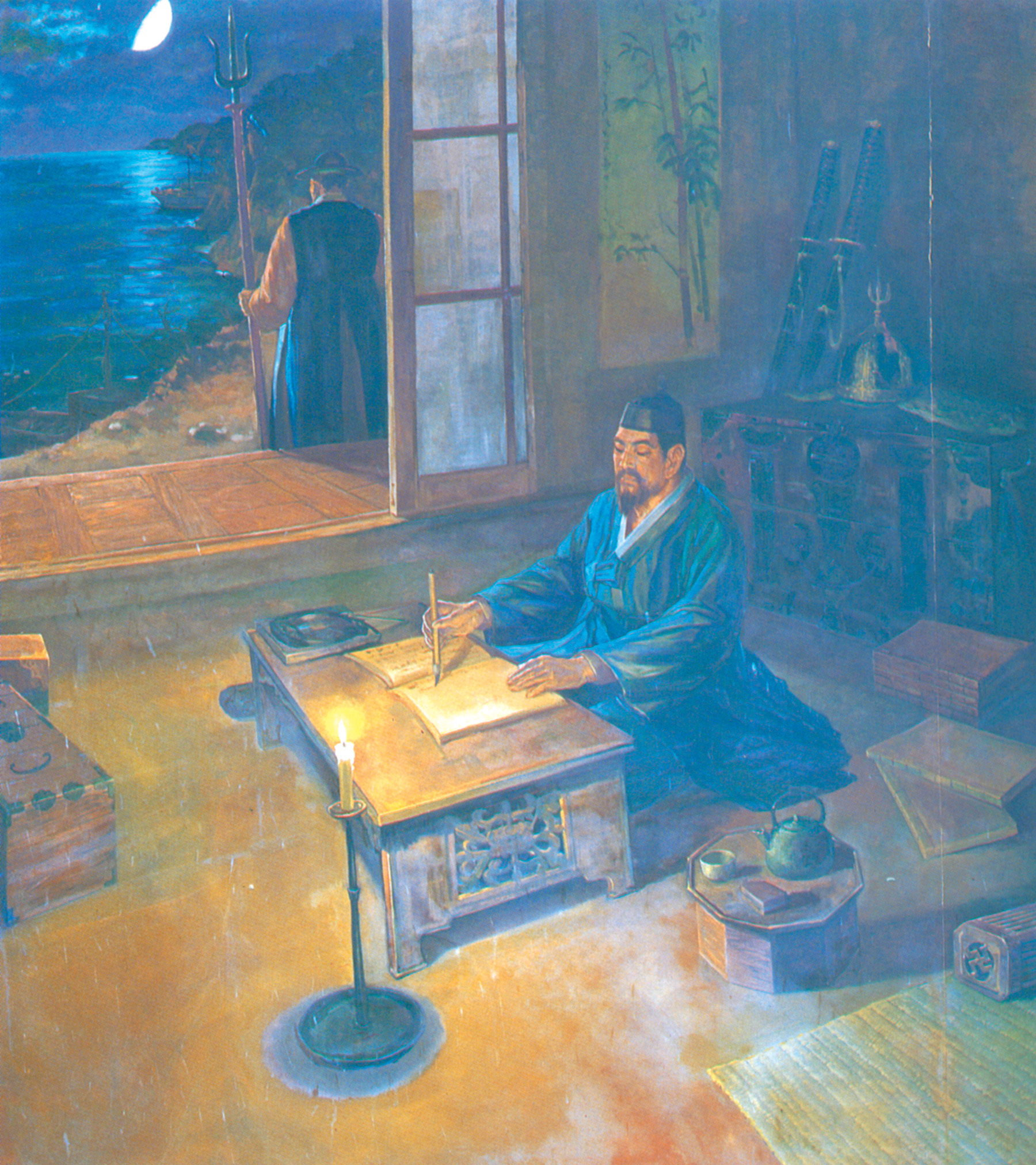

While en route to the Indian Ocean and before becoming completely incapacitated by illness, d’Orves formally turned over command of the squadron to Suffren, giving him full discretion to plan and execute the upcoming campaign. D’Orves died on board Heros on February 9, 1782, two days after arriving off India’s Caramandel Coast.

Over the next 17 months, Suffren fought five battles against Sir Edward Hughes in the last French attempt to contest British supremacy on the Indian subcontinent. Rather than a distant sideshow, Suffren fought his campaign as if the fate of France depended on it.

Political necessity required Suffren to stay close to India’s Caramandel Coast and the nearby island of Ceylon. France’s only Indian ally, Haydar Ali, had been less than satisfied with France’s lackluster performance to date, and Suffren felt his squadron’s presence was required to keep Haydar Ali from concluding his own separate peace with England. Likewise, while the British captured Trincomalee, the main port on Ceylon, early in the war, the rest of the island was in Dutch hands, and Suffren intended to prevent the rest of the island from falling to the British as well.

A squadron at sea required an extensive amount of supplies, particularly masts and spars, and battle damage exacerbated the regular wear and tear tenfold. Neither Ile-de-France, two months away, nor Ceylon were rich in naval stores and Suffren had to accomplish administrative miracles to keep his squadron at sea. As he maneuvered between India and Ceylon, Suffren was forced to live off the land, so to speak, resupplying himself by capturing British merchant ships and cannibalizing his own transports for masts and spars. To replace crew losses from illness and combat, Suffren had to enlist ever increasing numbers of local Indian sailors. For his demonic energy, the admiring Indians called Suffren “Admiral Satan.”

Far more serious than difficulty with supplies, Suffren had to contend with the crisis of command. His abrasive personality, caustic tongue, and ungentlemanly manners quickly earned Suffren the enmity of most of his ships’ captains. In an atmosphere where promotion to command capital ships was reserved almost exclusively to members of the highest nobility, junior officers of aristocratic birth frequently treated their superior officers as social equals.

Although not outright insubordinate, Suffren’s captains frequently used any excuse to misunderstand and undermine his orders even to the detriment of their country. A good tactician, Suffren was not a good mentor, failing to instill his ideas in the minds of his subordinates, requiring obedience where initiative was needed. However, a crop of young, talented officers, which included two future admirals, served under Suffren and learned from him if not by direct mentorship, then from firsthand tactical experiences.

On February 14, 1782, Suffren discovered Admiral Hughes’ squadron at Madras, the main British base on the Caramandel Coast. Unlike Commodore Johnstone at Porto Praya, Hughes’ squadron was anchored in a line of battle, moving closer to shore under protection of the fortress guns after spotting Suffren.

The tactical situation did not favor the French. The following day Suffren continued south to Porto Novo, the only anchorage in the hands of Haydar Ali. Hughes correctly surmised that Suffren’s intentions were to either land troops farther south along the coast or continue southeast to Ceylon to retake Trincomalee. With neither option acceptable, Hughes immediately gave chase to spoil Suffren’s plans, even though the French outnumbered the British 11 ships-of-the-line to nine.

Throughout February 17 the two squadrons maneuvered closer to each other near the small town of Sadras. Gaining advantage of the wind gage, Suffren intended to double the rear of the British line, with his division of five ships coming up on the British windward side and Tromelin’s division of six ships on the leeward. At 3 pm Suffren raised the signal to execute the doubling maneuver and close to within pistol range.

Two hours later Suffren’s division closed with the British line from the rear. Suffren, in his flagship Heros, sailed along the British formation and lined up with Hughes’ flagship, Superb. Behind Suffren Orient, Sphinx, Vengeur, and Petit Hannibal faced off against Exeter, Monarca, Isis, and Hero.

Although he was flying the signal for a close engagement, Suffren began firing from afar. Tromelin, possibly deliberately, misunderstood or chose to ignore Suffren’s signals to engage and ordered his division to remain in line behind Suffren rather than enveloping the rear of the British formation. However, two captains from Tromelin’s division, Saint-Felix in Brillant and Cuverville in Flamand understood Suffren’s intentions and on their own brought up their ships to double the last two British vessels, Monarca and Exeter.

For a long hour the five ships in Suffren’s division exchanged largely ineffective fire with the British ships opposing them. Only Exeter at the rear of the British line was in real danger as she was being shelled from two sides by the French. By 6 pm, when the leading ships in the British formation began coming around to assist their rear guard, Suffren gave orders for his squadron to draw off.

Even though Exeter was battered and Superb damaged, Tromelin’s failure to double the rear of the British line resulted in the first contest between Suffren and Hughes to end in a draw. The British lost 32 men dead, including the captains of Superb and Exeter, and 95 wounded, while French losses came to 30 killed and 100 wounded. Hughes continued southeast to Trincomalee for repairs, while Suffren sailed to Porto Novo where he disembarked French troops. In April the French ground forces captured the small coastal town of Cuddalore, which became Suffren’s frequent refuge for repairs and the source of fresh water.

The next engagement between Suffren and Hughes occurred in April 1782 in what became known as the Battle of Providien. The two squadrons sighted each other on April 9 and for three days maneuvered adroitly in an attempt to gain the wind gage as they maneuvered near Ceylon. On April 12, concerned that the French would overtake his rearmost ships, Hughes deployed his squadron in line of battle. At 11 am, approaching the rocky islet of Providien south of Trincomalee, Suffren gave the order for his ships to close with the British, each aiming for one of the enemy. With a dozen French ships against 11 British vessels, Suffren intended that his extra ship double the rearmost British vessel.

Approaching within range of a musket shot, Suffren gave orders to attack. Again, the French captains failed to execute Suffren’s orders. The four rearmost ships, Severe, Ajax, Annibal, and Flamand, were too slow to engage and began firing from afar. Bizzare, whose assignment was to double the rear of the British line, was not able to execute the maneuver despite repeated urgings from Suffren.

A vicious fight flared up in the center of opposing lines between the French Heros, Orient, and Brillant and British Superb and Monmouth. The two flagships, Heros and Superb vigorously exchanged broadsides until a fire broke out on Superb, forcing her to veer out of line. Heros shifted fire on Monmouth, which lost her main and mizzenmasts under relentless battering.

As Superb extinguished the fire and reengaged, the two lines became disordered and continued exchanging fire as they moved closer to Providien’s shore, which was treacherous with reefs and sandbanks. Not wishing to risk fighting in shallow water, in the late afternoon Hughes ordered his squadron to engage Suffren on the port tack and the French followed, but no further action took place that day. At dusk the two squadrons dropped anchor two miles apart, ending one of the bloodiest French-British naval conflicts to date. Once again, Suffren’s plans were foiled because his captains failed to execute prescribed maneuvers. French losses came to 139 dead and 364 wounded, while the British lost 137 dead and 437 wounded.

On July 5, 1782, Suffren arrived off British-held Negapatam, intending to drive off Hughes’ squadron and take the town by a naval landing. The morning of July 6 was spent maneuvering. In the late morning, Hughes, gaining the wind gage, ordered his squadron to close with the French. At 11 am the leading ships began exchanging fire.

Even though Suffren had 12 ships-of-the-line against Hughes’ 11, Ajax had lost two masts the previous night and quickly fell behind, leaving the two squadrons at 11 ships-of-the-line each. The vessels in the rear of both squadrons failed to come to grips at close range and exchanged largely ineffective broadsides from a distance. For the next hour and half, the center and van sections of two squadrons battered each other until Brillant and Flamand on the French side and Exeter and Hero for the British were severely damaged.

Severe found herself set upon by Sultan and Burford. Under merciless pounding, Severe’s Captain De Cillart lost his heart and ordered the ship’s flag lowered as a sign of surrender. Two of his officers intervened and persuaded Cillart to raise the flag again and resume the fight. The struggle went on as the wind continuously changed directions, disordering both squadrons. After four hours of fighting, the firing gradually died down and the two squadrons finally anchored at 6 pm.

Although the French suffered far more in casualties—78 dead and 601 wounded against Hughes’ 77 dead and 232 wounded—damage to British ships was greater. This prevented the British from pursuing the French. Nevertheless, Suffren was unable to drive off Hughes and had to give up his plans to capture Negapatam.

Upon returning to Cuddalore, Suffren dismissed four of his captains for lackluster performance during the battle. The cashiered officers were his cousin Claude Forbin of Vengeur, François Maurville of Artesien, Alexis Cillard of Severe, and Francois Bouvet of Ajax. Taking into consideration Bouvet’s brave previous service, Suffren arranged for his resignation for health reasons. Bouvet’s health deteriorated quickly and he passed away on October 6, 1782. Tromelin, having fought well at Negapatam, was retained in his present position.

Suffren set sail for Ceylon on August 1 after stripping Cuddalore bare of supplies. He also took materials from ships in port and homes in the town to repair his ships. A week later Suffren linked up at Batticoloa with two ships-of-the-line carrying 600 soldiers and one corvette that had just arrived from France.

British-held Trincomalee, with its good harbor, located only 50 miles north of Batticoloa, and Suffren used this opportunity to capture it. On August 23, after a short bombardment from the ships, the French landed a force 2,300 men. Four days later the small British garrison of Trincomalee surrendered.

Too late to save Trincomalee, Hughes arrived from Negapatam on September 2, having linked up with his own reinforcements en route. Suffren came out of the bay to meet Hughes the following day. In addition to the 14 ships-of-the-line, Suffren placed the large 36-gun frigate Consonant to lengthen his line of battle against Hughes’ 12 ships-of-the-line. After several hours of maneuvering, frustrated with the sluggishness of his captains in forming the line of battle, at 2:30 pm Suffren gave the signal to close within pistol-shot range of the enemy. To hasten the laggard captains, Suffren ordered a gun fired from the upper deck of Heros. The officers commanding gun batteries on lower decks misunderstood the shot as the signal for action and began firing full broadsides. Other ships quickly joined in and the Battle of Trincomalee began at longer ranges than Suffren intended.

Suffren ordered Venguer and Consonant to double the rear of the British line. However, the maneuver failed and Venguer, having lost her mizzen mast, had to move out of the line, while the captain of Consonant was killed. The French van failed to close as well and the main action was fought in the center, with Heros, Illustre, and Ajax set upon by Superb, Burford, Sultan, Eagle, Hero, and Monarca. “The enemy formed a semicircle around us and raked us ahead and astern,” recalled one of Suffren’s officers.

By 5:30 pm the wind shifted in French favor and several of Suffren’s ships in the van and rear were finally able to close in and assist the center. Thirty minutes later both Heros and Illustre lost their main and mizzenmasts and Ajax was badly battered. When Heros’ mainmast fell, it carried her flag with it, and the British gave a great cheer thinking the enemy flagship had surrendered. Suffren quickly raised another flag, but the situation remained serious. Under cover from Artesien, the two dismasted ships were towed away and falling darkness again brought an end to the fighting. The next morning the French returned to Trincomalee while the British retired to Madras for repairs.

French losses came to 82 dead and 255 wounded, with most of the casualties occurring on Heros, Illustre, and Ajax, while five of French ships suffered no casualties at all. The British suffered heavily as well, losing 51 killed, including the captains of Isis and Sultan, and 283 wounded. Several of his ships “were taking much water from shot-holes so very low down in the bottom as not to be come to be effectively stopped; and the whole had suffered severely in their masts and rigging,” recalled Hughes.

On September 23, the captains of the vessels that did not engage at Trincomalee, Tromelin of Annibal, La Landelle of Bizarre, St. Felix of Artesien, and Morard de Galles of Petit Annibal asked to be relieved, citing ill health. Tromelin, whose health was already failing, was no loss to Suffren. Both Saint-Felix and Morard de Galles were capable captains and their request was a vote of no confidence in Suffren. Many of Suffren’s senior officers thought the war, or at least their part of it, was unwinnable, which could partly explain their lackluster performance in combat.

Tromelin was eventually dismissed from service in 1784 without pension but reinstated during the Revolution as vice-admiral. Saint-Felix and de Galles, after cooling their heels at the Ile-de-France for a time, returned to Suffren’s squadron and were reinstated to command.

With the monsoon season fast approaching, the opposing squadrons needed to find sheltered harbors. Hughes departed for Bombay on the western coast of India, where the British traditionally wintered. Suffren took shelter at Aceh on the northern tip of Dutch-controlled Sumatra on the other side of the Bay of Bengal.

Returning to the Coromandel Coast in February 1783, Suffren discovered that Hydar Ali had died in December and his struggle against the British continued under his son Tipu Sahib. On February 15, 1783, Suffren arrived in Porto-Novo and, after a brief contact with Tipu Sahib, departed for Trincomalee the next day. Dispatches reached him in Trincomalee on February 26 announcing his promotion to chef d’escadre for his battle at La Praya. The good news was shortly

followed by the bad when the new French supreme commander in the East Indies, Marquis Charles de Bussy-Castelnau, arrived from France at the end of March with a small detachment of troops and another ship-of-the-line

Bussy had had a distinguished career in India during the Seven Years’ War but was a shadow of his former self when he returned to India in 1783 at the age of 67. Besieged by multiple illnesses and suffering from gout so severe that he could not ride a horse, Bussy conducted a lackluster land campaign before being bottled up in Cuddalore by the British in early June.

Under orders from Bussy, Suffren arrived off Cuddalore on June 13, 1783, to discover Hughes’ squadron blockading the town in support of the landward siege. Sighting Suffren, Hughes moved off and anchored five miles from Cuddalore, lifting the naval blockade and allowing Suffren to make contact with Bussy. Understanding that the naval action would decide the fate of the siege, Bussy embarked 1,200 soldiers to bring the crews of Suffren’s ships-of-the-line to full complement.

The two squadrons began closing for action on June 20, 1783. Among his latest dispatches, Suffren received orders from the naval minister to be aboard a frigate during future engagements. This measure was taken to avoid the fate of the commander of the West Indies squadron, Admiral François de Grasse, who was taken prisoner the previous year during the Battle of Saintes when his crippled flagship was forced to surrender. In accordance with his orders, Suffren raised his flag on the frigate Cleopatra for the Battle of Cuddalore.

On June 22 the two squadrons began drawing closer again; however, with an outbreak of scurvy rampant on his vessels and drinking water running short, Hughes withdrew and returned to Madras. Despite the lack of dramatic events, the last battle of the war was a strategic victory for the French. The uninterrupted resupply of Cuddalore by sea made the siege of the town pointless and the British land forces withdrew the next month.

Anchored off Cuddalore, on June 29 Suffren received news that preliminary peace articles had been signed five months earlier in Paris. This was bittersweet news. Had it not been for the long delay in navigation from Europe, the battle on June 20, which resulted in hundreds of casualties, would have been unnecessary.

Suffren left Indian waters on October 6, 1783, shortly after receiving news that he had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, the equivalent of vice admiral. Hughes remained off India for a time, assisting British land forces in dealing with Tipu Sultan’s Mysoreans, while the bulk of his squadron sailed for England. After the final provisions of the peace treaty were ironed out, the European powers in India and Ceylon returned to the way things were before with the exception of Negapatam, which passed into British possession.

During the five battles between Suffren and Hughes, no capital ships on either side were sunk or captured. After making a stop at Ile-de-France on his way back to France, Suffren put in at the Cape Colony on December 22, finding nine ships from Hughes’ squadron at anchor there. Nine British captains who recently faced Suffren over the barrels of their guns, as well as several officers from neutral vessels, came aboard Heros to enthusiastically greet the French admiral as a master of the profession. An enthusiastic welcome and an audience with the king greeted Suffren upon his return to France.

Suffren died on December 8, 1788, during a visit to Paris and was buried with great honors at the Order of Malta’s Temple Church in Paris. Among his many decorations and offices, he held the lofty rank of bailiff in the Order of Malta.

During the Reign of Terror in 1793 following the French Revolution, Parisian mob desecrated Suffren’s tomb. The Temple Church fell victim to revolutionaries’ efforts to eliminate all traces of the Old Regime, being razed to the ground in 1796.

Once the fervor of the Revolution died down, Suffren’s legacy was rehabilitated in the hearts of his countrymen. “Why, did he not live until my time?” Napoleon Bonaparte lamented in exile. “Why could not I find someone of his kind? I should have made him my Nelson and our affairs would have taken a very different turn. Instead I spent all my time looking for such a sailor and never found one.” Multiple French navy ships bore Suffren’s name and a statute of the corpulent admiral graces the quay of his native St. Tropez.