By Christopher Miskimon

During the late morning of August 8, 1944, the day famed tank commander Michael Wittmann would meet his end in combat, German SS-Oberführer (Colonel) Kurt “Panzer” Meyer sat in his staff car as his driver made his way toward the town of Cintheaux, France, near the front lines. A British attack was underway, and Meyer commanded the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitler Youth, directly in the enemy’s path. As the two men proceeded north, a dismaying sight greeted them. Scores of German infantrymen were moving southward, retreating in disarray. The scene was one of utter chaos, something Meyer immediately set out to change. Taking up his carbine, the SS officer sprang from the staff car and waded into the midst of the fleeing men. Alone, he exhorted to his men to stop running and rally to him. Making a brave display, his urging succeeded and the men around him were restored to order.

Soon after, Meyer met with Sturmbahnführer (Major) Hans Waldmuller, a member of his unit. They drove to a gently sloping rise in the terrain near the village of Gaumesnil. There they found a barn and climbed to its top carrying their binoculars. What they saw no doubt daunted them. In the distance the spearheads of two British armored divisions were assembling to resume the Allied attack. Tanks, halftracks, and Bren carriers were spread before them like an enormous pride of lions, predators ready to close in for the kill.

Meyer knew there was little behind him to stop this wave of destruction from advancing all the way to Falaise. If they succeeded the German defenses for this entire region might collapse. His troops were too weak to defend, so he decided they would attack instead. Meyer quickly issued orders for all the Hitler Youth forces in the area to counterattack north at 12:30 pm. It was a desperate move, but if it worked the British timetable would be disrupted, allowing time for other German units to arrive and man prepared defensive positions farther to the rear. They had only a half hour to prepare.

All the troops in the immediate area were under Waldmuller’s command. There were about 20 tanks from SS Panzer Regiment 12, most of which were Panzer IV models. With them were about 500 infantrymen from I Battalion, SS Regiment 25. However, the force Meyer was most likely depending upon to tilt the balance in his favor were the heavy Tiger tanks of the 2nd Company, SS Heavy Tank Battalion 101, under the command of Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Michael Wittmann, a panzer ace with many tank kills to the credit of himself and his crew. Though Meyer could not have known it, he had just given the orders that would send the famous Wittmann to his death.

Michael Wittmann’s 139 Kills as a Panzer Ace

Thanks to the skilled machine of Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels, Michael Wittmann was a national hero in wartime Germany. He was born just before the start of World War I, on April 22, 1914, the son of a farmer. As a young man he served two years in the German Army before enlisting in the SS, joining the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, a regiment-sized unit later expanded to division strength. When the war began Wittmann served in the 1939 Polish campaign and the Balkan invasion of 1940. The young soldier was promoted to Oberscharführer (sergeant) during the early months of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, where he showed a knack for knocking out enemy tanks. Sensing his ability, his superiors sent Wittmann for officer training. He returned to the unit in December 1942 and was assigned to the division’s Tiger tank company. As a member of this unit he fought with distinction at the Battle of Kursk.

After the battle his company was used as the cadre of the newly formed SS Heavy Tank Battalion 101. In January 1944, Wittmann was awarded the Knight’s Cross for his record of more than 90 enemy tanks destroyed. By March he was in command of his company. The battalion was transferred to France just in time to meet the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Thrown into the battle, Wittmann’s battalion fought hard, and the toughness of their Tiger tanks caused much consternation among Allied troops.

On the morning of June 13, 1944, his company was positioned near the French village of Villers-Bocage in expectation of a British attack there. His company was only at about half strength. When the British attack came sooner than expected, Wittmann and his Tigers went into action, destroying around 30 vehicles and antitank guns; at least 10 British tanks were lost. During the furious battle Wittmann’s own Tiger was disabled, so he and his crew fled on foot to the safety of German lines. The panzer ace would continue to fight, amassing a tally of 139 tank kills before his death in August.

Pressed For Time in the Falaise Pocket

The battle in which Wittmann met his doom was part of the larger action surrounding Operation Totalize, a British offensive aimed at capturing the high ground around the city of Falaise. German forces were gradually being trapped in a pocket nearby and seizing Falaise would help seal that pocket. The operation was under the command of Canadian General Guy Simonds, the II Canadian Corps commander. The plan for Totalize involved several phases. In the first, a pair of infantry divisions would attack along the main road leading from Caen to Falaise. Seven mobile columns would infiltrate between the Germans’ forward defensive positions toward targets deep in the Nazi rear area. These columns were tank heavy, and the assigned infantry were mounted in armored vehicles to maintain a rapid advance. The bypassed positions would be finished off by more infantry following behind the mobile columns.

The attack went well, and by noon of August 8 the German lines had been pierced to a depth of six kilometers. This gap was particularly bad in the area of the German 89th Division, where Meyer and his Hitler Youth were placed. In front of them the second phase of the offensive was beginning. The Canadians and British were unaware the Germans were in such disarray and were waiting for an airstrike planned for 12:26 pm. This strike was composed of 681 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers hitting six separate targets during the early afternoon. The two British tank divisions Meyer had watched from the barn were only waiting for the airstrike to begin their attack.

While Meyer and Waldmuller planned the counterattack, Wittmann and four of his Tigers were sitting behind a tree-lined hedgerow about 600 meters southeast. Their crews had carefully camouflaged them to protect against the incessantly roving Allied fighter bombers. Within minutes Wittmann received a call to meet with Meyer and Waldmuller in nearby Cintheaux. His own tank, Tiger 205, was undergoing repairs so he was using Tiger 007, the battalion commander’s vehicle. It took only a few minutes for the tank to arrive there; Wittmann joined his two superiors as they finished their plans.

As they gave Wittmann his orders for the impending attack, all three saw a sight that spurred them to move even more quickly. A single Allied bomber flew overhead, flares dropping from its bomb bay. Meyer had seen this before; the plane was marking the target area for a massive airstrike. The bomber force was likely less than 10 minutes away. It made the counterattack even more necessary. If the German troops stayed where they were the bombers would decimate them, leaving them an easy target for the advancing British tanks. The attack had to start now. Wittman rushed back to his tank and rejoined the other three. The camouflage was hastily torn away, and soon all four tanks were moving north. Accounts vary, but at least one more Tiger, possibly another three, also moved toward the British from a few hundred meters east.

“Churchill is Sending a Bomber For Each of Us!”

To the north, the British waited to advance. One of their units, the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry, was an armored unit equipped with M4 Sherman tanks. This unit had formed a task force with a battalion of the famous Black Watch. Together they had seized the town of St. Aignan the night before. During the battle the tanks of A Squadron engaged four German self-propelled guns, losing a trio of Shermans from Number 2 Troop. Two of the enemy vehicles were knocked out by the Troop’s Sherman Firefly, an up-gunned Sherman mounting a powerful British 17-pounder cannon. After defeating the Nazi armor, the British broke through to St. Aignan, capturing it at around 4:30 am. The remaining tanks of A Squadron took up defensive positions in a group of orchards southwest of the town known as Delle de la Roque.

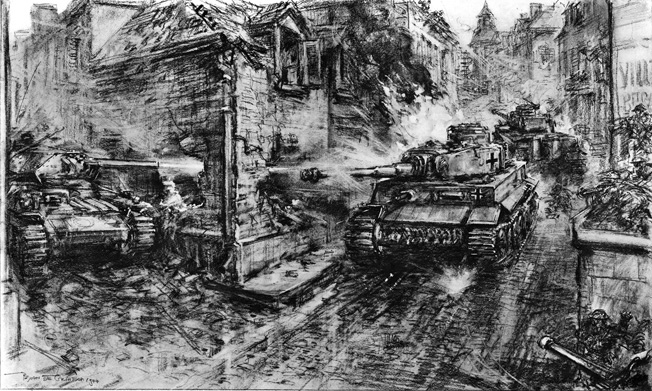

The experienced German troops of the Hitler Youth got their spoiling attack underway quickly. Wittmann’s tank and three other Tigers rumbled slowly north-northwest one after another in a column. Artillery fire rained down upon them but did not stop their advance. To the northwest were British tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, another Sherman-equipped outfit with a few Fireflies in their order of battle. The column formation gave them some protection, and the German tanks stopped occasionally in the small low spots of the terrain to return fire at the distant British tanks. The range was long, around 1,800 meters, but that was still close enough for their deadly 88mm cannon to knock out several Shermans. Wittmann’s Tigers continued their northwestward counterattack unaware that A Squadron of the Northamptonshire Yeomanry was to their northeast, concealed in the orchards.

Wittmann’s movements were being watched by Meyer and his medical officer, Doctor Wolfgang Rabe. They watched their own tanks move through the enemy barrage, exchange fire with the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, and continue their advance. No sooner had they done so than the sky to the north filled with Allied bombers. A German panzergrenadier near Meyer remarked, “What an honor! Churchill is sending a bomber for each of us!” They all began to run north from the village into the surrounding fields. Just as they cleared the village, bombs began raining down on it.

Firefly Ambush From the Orchards

The western side of the Delle de la Roque orchards was occupied by A Squadron’s 3 Troop. The unit was led by a Lieutenant James and was slightly understrength, having three standard Shermans and one Firefly, commanded by a Sergeant Gordon. A hedgerow lined with trees provided cover to the troop’s tanks as their crews watched for the enemy through gaps in the hedge. Soon they saw Wittmann’s Tigers moving generally north at a distance of 1,200 meters. Gordon radioed the squadron headquarters informing them of the sighting. He was told to hold his fire until the squadron’s second in command, Captain Boardman, arrived.

Boardman reached 3 Troop quickly in his own tank as sporadic German mortar and artillery fire started falling around the orchard. As they all watched, the Nazi armor continued moving in the same direction, apparently unaware of the British tankers watching them. This emboldened the Englishmen to wait, allowing the Tigers to get closer. Soon the range was down to 800 meters, and the Tigers were moving perpendicular to the orchard, exposing their thinner side armor. The Firefly could destroy a Tiger at this range, but it was still doubtful for the regular Shermans, so Gordon told the other tank commanders to stay put while his Firefly engaged the distant Tigers. It was 12:39 pm.

Gordon had his tank move forward until it was just outside the orchard’s southern edge. This gave the Firefly a better field of fire to take on the Tigers. The tank clanked forward, Gordon keeping his head out of the hatch, leaving him more exposed but giving him a better view of his targets. He apparently could see only three of the Tigers and told his gunner to engage the rear vehicle. With a little luck, the other two crews would not notice the destruction of their fellows, giving Gordon and his men more time to fire on them.

The gunner, Joe Ekins, aimed carefully through his sight at the chosen Tiger. He was known in the unit as a crack shot despite the fact he had only fired a half-dozen 17-pounder rounds in his life. The young man was nervous. Despite his fear, he later recalled his thoughts were rather more aggressive: “Get the bastard before he gets you.” Ekins took careful aim. The 17-pounder gun created a violent muzzle blast and pressure inside the tank when fired. As Ekins made ready, the crew covered their ears, closed their eyes, and opened their mouths, all to reduce the effect of the gun on their tender human forms.

When Gordon gave the order, Ekins pushed his right foot down on the floor-mounted button for the main gun. With a great noise, flash, and rush of fumes, the cannon fired, sending a projectile toward the Tiger at almost 3,000 feet per second. His loader quickly slammed another round into the cannon’s chamber, and Ekins fired again. Both rounds struck true, and within moments flames engulfed the once fearsome Tiger. With its firing position now revealed, Gordon ordered the Firefly’s driver to pull back into the orchard to avoid any return fire.

It proved a wise decision. As the British tank backed up, the turret of the second Tiger in line began to swing toward them. As soon as it faced them, the German tank fired a heavy 88mm round. Luckily, the enemy gunner missed, though he sent two more rounds past them as the Firefly disappeared into the cover of the trees. Ekins recalled watching the turret of the Tiger traversing toward him, likening the 88mm gun to something that might sit on a battleship, it appeared so big. Unfortunately, he then realized his tank’s commander was gone!

Unbeknownst to the crew inside the tank, Sergeant Gordon’s risk in keeping his head outside the hatch had not paid off. As the enemy’s last round rushed by the tank, Gordon’s hatch had crashed down on his head. No one knows if this was caused by the 88mm projectile striking the hatch, a tree branch, or simply the motion of the tank, any of which can cause an unsecured hatch to swing shut. Gordon was nearly unconscious from the impact and staggered down from the turret. Even worse, the hapless Gordon was almost immediately wounded as German indirect fire adjusted into the orchard. With both a head injury and shrapnel wounds, the Firefly’s commander was out of the fight.

The Death of Wittmann

The troop commander, Lieutenant James, decided to take command of Gordon’s tank and continue the fight. It was a prudent move since the Firefly was the only tank able to take on the remaining Tigers. He dashed to it from his own Sherman, running through the German fire and climbing up the vehicle and into the hatch. Once there he ordered the driver to move to an alternate firing site, something a well-trained crew would have picked out whenever they occupied a new defensive position. It took a few minutes, but at 12:47 the Firefly was ready for another go at Wittmann’s tanks.

James told the driver to pull forward so they could fire. He did so, exposing the tank but giving Ekins a chance to engage the Tiger that had fired at them a few minutes earlier. Once again the crew braced for the shock of firing the main gun as Ekins aligned his sights on the second Tiger. Whether he noticed the number 007 painted on the turret sides is unknown, though he was likely concentrating on the side of the hull, where the armor was thinner and there would be more of the tank in the gunsight surrounding his exact aiming point. Ekins received the order to fire and again pushed down his right foot, the sole of his boot depressing the firing button.

The muzzle flash was blinding, and for a second or two Ekins and his fellow crewman did not know if he hit the target. Any fears were allayed, however, when the air in front of the Firefly cleared, showing smoke coming from the Tiger. Even better, within a few seconds a large explosion filled the air with flame and smoke. The Tiger’s ammunition had cooked off, throwing the tank’s turret high into the air. Though the Firefly crew could not have known it, they had just ended the career—and life—of one of Germany’s most famous panzer aces.

Despite Wittmann’s death, the battle was not over. James ordered the Firefly to back into the orchard again, away from any fire the remaining Tiger could send their way. According to British accounts, a few Shermans with 75mm guns now tried to engage the last Tiger (these accounts never mention any other Tigers present though it is fairly certain there were more). They moved to close the range so their slower-moving rounds might knock out the Tiger. Numerous rounds pelted the German vehicle like hail. This appeared to rattle the driver as the tank began to move around, changing direction rapidly even though none of the rounds penetrated the armor. One British observer recalled the Tiger seemed to be “milling around wondering how he could escape.”

Even Captain Boardman ordered his tank forward to engage the remaining Tiger, and Lt. James soon had the Firefly come back out to shoot at it. At this point the accounts differ; Boardman claims his tank fired a round that stopped the panzer, but Ekins remembers differently. He recalled the Tiger was still in motion when he put two 17-pounder rounds into it. This caused the tank to burst into flame. Ekins did not see any of the crew get out. The time now was 12:52. In less than 15 minutes a single Firefly had destroyed three Tigers with only five rounds of ammunition. Even better, a few minutes later a different Firefly destroyed two Mark IV panzers with only two shots at the extreme range of 1,645 meters. The action ended with the British scoring a lopsided victory while Germany lost one of its war heroes and at least five precious tanks, three of them irreplaceable Tigers.

This short but sharp battle showed the grim reality of tank warfare. While volumes can be written on the technical specifications of various tanks or the training and experience of their crews, warfare is more than just lining up a given number of tanks on each side and having them go at each other. Air and artillery support each had their effect on this fight. When German tank units were fighting defensively they caused damage out of proportion to their numbers. When they were attacking, which became increasingly rare in the West as the war continued, their losses grew significantly.

In combat between tanks, the crew that spotted the enemy first and fired first generally had a significant edge over their opponent, technical details or previous crew experience notwithstanding. The skilled use of cover and concealment also factor into battlefield victory along with aggressiveness, terrain, and pure luck. All of these things combined on August 8, 1944, and resulted in the death of one of Germany’s greatest tank officers in a few minutes of fighting. Despite their nominally superior tanks and likely greater experience, the Tiger force failed to knock out or even damage a single Sherman. In this instance the German advantages were negated by a skillfully conducted ambush.

Who Killed Michael Wittmann? A Debate to This Day…

The details of the battle as they are conveyed here are contested by some, though this is largely accepted as the most likely version of events. When Joe Ekins opened fire on the rearmost Tiger he could see, there were other tanks firing at them from the Sherbrooke Fusiliers at a range of about 1,100 meters. When he engaged Tiger 007 a few minutes later, those Canadian tanks were still nearby and may have been firing at Wittmann’s panzers. Some claim a shot from one of their Fireflies ended the panzer ace’s days. Some have even claimed a Hawker Typhoon fighter bomber destroyed Wittmann’s tank with a rocket, though a study of the 2nd Tactical Air Force’s logs largely disproved this theory.

The confusion inherent to any battlefield renders difficult any conclusive answer to the question of who killed Michael Wittmann. While it could have been someone else, postwar research and the consistency of the Northamptonshire Yeomanry’s war diary when it is compared to what is known from the German side make a convincing case that Wittmann met his death at their hands. German accounts denote only one Tiger, Number 007, had its turret blown off when it was destroyed that day.

even on the face of German tank ace

Michael Wittmann, photographed in Normandy in June 1944, shortly before his death.

Doctor Rabe saw several tanks go up in flames. He attempted to find surviving crew members, but British fire kept him back. He waited two hours for any survivors to make their way back to German lines, but none did and he eventually withdrew. After the battle the dead panzer crewmen were buried in an unmarked grave. Decades later they were located and reburied at a military cemetery in La Cambe, Normandy. Wittmann’s body was identified, and today his grave is marked with a small tombstone.

Joe Ekins survived the war and returned home to work in a shoe factory and raise a family. For the most part he stayed out of the arguments about who killed Wittmann; he had not even known Wittmann was in one the Tigers he shot up until eight years after the war. He never claimed to be solely responsible for killing Wittmann, and in all fairness the battle was a group effort by several British and Canadian units. In an interview before his death, Ekins did state, seemingly without rancor and matter of factly, that Wittmann, having willingly served Hitler and the Nazi regime, got the fate he deserved. Ekins passed away in 2012.

Certainly, the battle that ended Wittmann’s life gained more notoriety after the war. Only in the succeeding decades have the details and controversies of August 8, 1944, arisen. Though it is now seen as a great feat of arms, the war diary of the Northamptonshire Yeomanry summed it up at the time with studied understatement. “Three Tigers in 12 minutes is not bad business.”

Author Christopher Miskimon is a regular contributor to WWII History. He writes the regular books column and is an officer in the Colorado National Guard’s 157th Regiment.

What a really great article. I visited Michael Wittmans grave but I could not see Bobby Voyles name. Why was that?

I visited La Cambe in 2010 and saw Wittmann’s grave. While there, three German tour buses arrived and a large group of Germans places flowers on his grave. He is not forgotten in Germany.

Balthazar ‘Bobby’ Woll survived the war – he was off duty sick and his place had been taken by Gunther Riemann on the 8th August. He was for many years the leading light of the Knights’ Cross Legion on his home city – I believe to have been Hamburg.

Balthasar (Bobby) Woll was NOT in that tank and was in a hospital recovering from injuries. He was Wittman’s gunner and died in 1996 or 97. These German’s may have been heroes to some but they served in a branch of Hitler’s military that was responsible for the deaths of over a million people in concentration camps and this branch, the Waffen SS was declared as a criminal organization. Not a damn thing heroic about them and when armed Jews shot some of them in the Warsaw Ghetto they ran like kicked dogs and it took 6 weeks to get rid of these brave people. The initials SS stood for SchuetzStaffel or GuardSquadron and should mean ScheissSquadron and must be condemned for what they were, criminals.

Bobby actually ended up surviving the war. By that time as a receipt of the knights cross he was a tank commander himself. I believe at the time Wittman died Bobby was in the hospital recovering from wounds. He was a major part of Wittman’s success and the only tank gunner that received the knights cross.

Much of this is incorrect. Elkins did not hit Wittmann, he did not even see 007, but destroyed the other three. 007 was destroyed by the concealed Sherbrookes, which were far closer and actually Canadian, not British.

From the author: When I wrote this, I used the most accepted version of the event, but there are other versions, which I mention briefly in the piece. The men who were shooting at Wittman that day had no idea who he was at the time.

Whitman’s tank was at the very edge of the effective firing range of Joe Eiken’s firefly when it was destroyed and the closest tanks that could have been able to kill Wittmann were Shermans from the Candian Sherbrooke Fusiliers tank battalion.

That last picture of MIchael Wittmann shows a man with the ‘thousand yard stare’ probably just after Villers Bocage.

Interesting that Canadians killed air ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen in WWI and Canadians killed Tiger tank ace, Michael Wittman in WWII.

Actually pretty convincing evidence exists that it wasn’t CPT Roy Brown of the RAF who killed Von Richtofen, but rather an Australian machine gunner. This is based on the relative ranges and the angle that the bullet entered the Red Baron’s chest.

As much as I respect Canada’s part in the last 2 world wars and would not wish to demean her service and sacrifice for the good of mankind I think you will find that Manfred von Richthofen was brought down by an Aussie firing from the ground who only received recognition for this feat a few years ago.Apparently there are 3 claiments although none of these men tried to take credit for the kill.With respect to all combatants.

Battledetective.com has convincing evidence that the Canadians made the kill.

Very important ace panzer: Wittman. Great information, thank you.

Kurt Knispel was Germany’s the top tank ace, not Wittman. He had over 160 kills.

I believe Trooper Joe Ekins summed up best when asked about Wittmann “He invaded other people’s countries , killed men , women and children . He may be a hero to some ,not me “

I agree with Ekins the man and his tank had to be stopped , it was business

The battle damage to Wittmann’s Tiger, confined to one large-calibre shot hole in the rear left of the hull, clearly shows that the shot was fired from the ‘hole in the wall’ of Gaumesnil Manor House, to the West of Wittmann, and NOT from the NE, the location of the NY. The occupying unit there, that had knocked holes in the yard walls to give them a clearer view of the open fields to the East, where the Sherbrooke Fusiliers and their Shermans.

I agree with you on this statement it was one of the Shermans from the Sherbrooke Fusiliers that killed Wittmann not Joe Ekins

Reading through these comments people seem so sure with their statements. Im not tbh – the SFs had half distance and a flank shot (roughly) advantage over the NY with double the distance and an angled bow shot on 007 – but this was still within their effective range – more a long shot than the limit! The damage report of course could be priceless to the argument – does this exist?