By L. VanLoan Naisawald

In the fall of 1943, I found myself a “limited service” duty officer assigned to the Operations Division, War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. This agency had been established by Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall due to his lack of confidence in the response times of the old General Staff agencies.

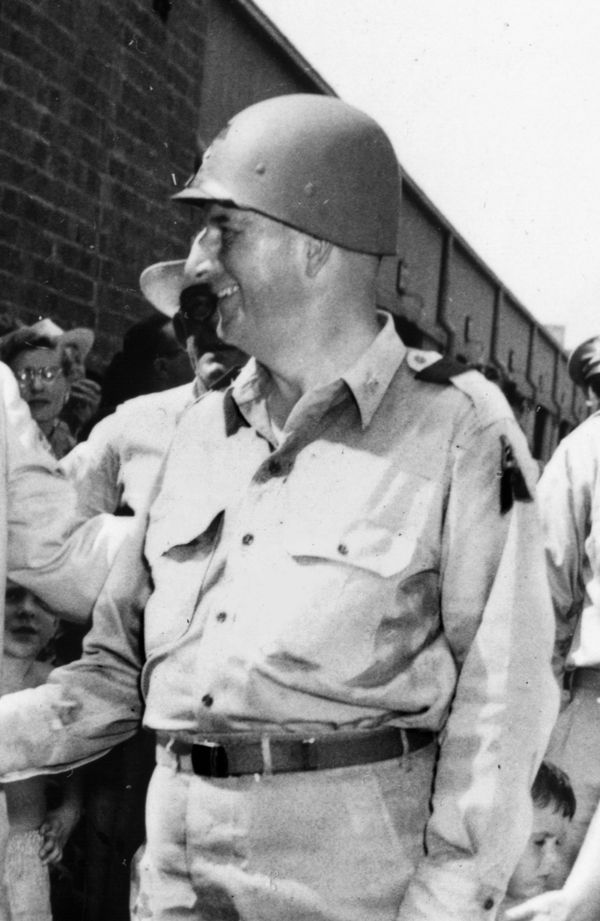

OPD, as it was called, was a relatively small agency headed by a two-star general, Tom Handy. He was supported by a small staff of senior officers, mostly young colonels and clerical support consisting mainly of limited-duty enlisted men. Through this agency came and went all the critical radio correspondence to and from General Marshall’s office to Army commanders worldwide. In effect, it was Marshall’s command post.

OPD was physically located on the third floor of the Pentagon, with its classified message center, of which I was a part, located directly beneath the War Department code room. All classified messages passed through this message center to and from the code room by pneumatic tubes. Handling these messages for OPD was a small staff of one senior lieutenant colonel, some six junior duty officers, of which I was one, and about an equal number of limited-duty enlisted sergeants.

We alternated duty tours from 8 am to 4 pm, from 4 pm to 12, and from 12 to 8 am, but the length of the tours invariably ran some 12 hours. The shifts were rotated periodically. The officers handled all Top Secret and Eyes Only messages, with the enlisted sergeants handling the others. Each message was read, and the reader determined which staff section in OPD would have responsibility. The message was then immediately delivered.

The highly classified ones were taken initially to the “front office,” where distribution was determined. In many such cases the number of copies sent down from the code center was limited—instead of the normal dozen or so, these came in but three to four copies. In extremely sensitive cases, we received only three copies from the code room, one for General Marshall, one for the White House, and one for General Handy. White House copies were hand delivered to Admiral William Leahy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s chief of staff—and no one else.

During my almost two years of duty there, I was privileged to encounter, either directly or indirectly, some of the key figures of World War II. But of all the messages received during my tour of duty there, those from General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell elicited the most enthusiasm and interest from all who saw them. All incoming messages were filed by month in a loose binder by point of origin, with the most recent being on the top. The last message from Stilwell during his retreat out of the jungles of Burma in 1942 read, “This radio’s getting too dammed heavy.” It was the last message from “Vinegar Joe” for some weeks, but those that followed later were gems.

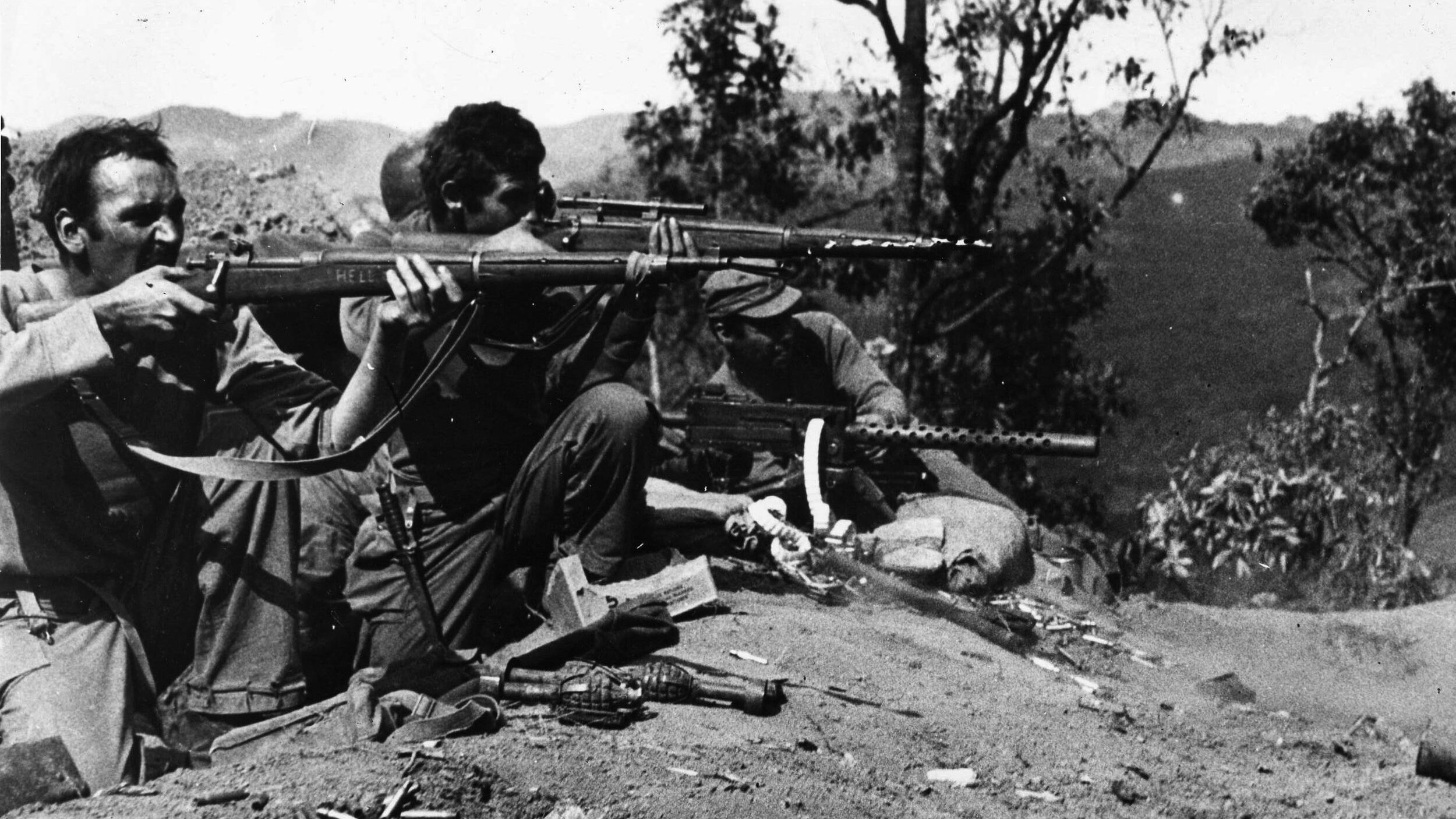

Messages from Stilwell were always eagerly awaited, so at variance were they from the more routine prosaic ones from other theaters. One message in early March 1943 caused us to feel a bit sorry for the general in his—what was then obvious to us—very difficult assignment. Writing to Marshall, he commented that in working on his “own small manure pile I am inclined to forget how much larger yours is….” He went on to say that if Marshall felt it best to sack him, to go ahead—it was always his ambition “to be a sergeant in a machine gun company.”

So interesting and so pithy were his personal messages that all of us eagerly awaited his frequent Eyes Only missives to General Marshall. These usually arrived at our desk about 2 am, making the night shift far more interesting. It was a known fact in the War Department that Stilwell had two intense dislikes—Chinese leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and anyone British! Chiang was usually referred to as “Shanker Jack, the Peanut, or the Gisimo.” I recall well one message in which he was so bitterly upset with the British position on some matter that I was directed to deliver it immediately, at about 6:30 am, to Marshall’s quarters at Fort Myer, Virginia.

A staff car took me there in a few minutes, and I was escorted into the breakfast room where the general was eating. I handed him the message as he was lifting a cup of coffee to his lips. As he read, he paused. Slowly he lowered the cup and turned to me. “Have you read this?” he asked. I replied that I had.

Marshall laid the message down and then paused for a minute before saying something to the effect that “This is a message to end all messages!” That evening a message went back to Stilwell telling him to cool down and play ball in a very difficult situation. We anxiously awaited Stilwell’s reply, which came back the next night. It read something to the effect that he would even stand up for some upcoming ceremony and wear a monocle. Stilwell added that he had only one good eye anyway!

Another testy message to Marshall and his people in OPD was a bitter complaint about the lack of support being given Stilwell in his effort to build up the Chinese Army. Materials promised were in India, he wrote, engineer construction equipment had consisted of a wheelbarrow and a bulldozer—with bull attached!

“I will be [expletive deleted] if I like playing the goat … if nothing can be done, OK, but … don’t go on telling me how great they are going to back me to the limit—This is the limit already!” Stilwell wrote.

A litany of pithy messages flowed from Stilwell over the years, castigating Chiang and his duplicity. Chiang’s wife also suffered at his hands. Madame Chiang was an immensely charming and influential lady, particularly with President Roosevelt. Stilwell, and to an extent those in OPD in the China-Burma section, felt her influence was less than helpful overall. It was the perception in OPD that Madame Chiang wangled promises out of the president that the Army was incapable of fulfilling except at the expense of other theaters. One case arose in March 1943, when a Chinese plea for more aircraft was being put forth as the way to end the war in China. The “Madame” was then heading for Washington, and Stilwell wired Marshall that he hated to think of the results “now that the Madame is let loose on a credulous public!”

So intense was the anti-Madame feeling at the China desk of OPD that this writer witnessed an exchange between the desk head, a full colonel, and his deputy, another full colonel, about who would go to the airport to greet Madame Chiang on her arrival. The junior colonel, a crusty, old, tobacco-chewing ex-cavalryman and former West Point football coach, flatly refused to go! Only by considerable persuasion from his friend and boss did he finally agree.

None of us in OPD had any doubts as to Stilwell’s belief in the effectiveness of the Chinese Army under Chiang. Blunt evidence of this came in a message to Marshall stating that if the Chinese Army was so full of fight and so well led, “What am I here for?” He went on to say that the Chinese leader just sat in his palace writing books and refusing to believe anything a “foreign devil” told him in reference to his own people. All the man felt he needed to win, said Stilwell, was more airplanes.

One suspects that the influence of General Claire Chennault, who had headed the original Flying Tigers and was now an Amy Air Forces commander in China, played a major role in this situation. To Stilwell, the constant praise Chiang and his army were receiving in the American press confirmed Chiang’s warped ideas.

One last story about Stilwell concerns one of his official visits to the Pentagon. The OPD message center was located on the ninth corridor, just off the E-Ring of the Pentagon, where all the really senior officials were located. One morning I followed a warrant officer named Bond, who ran the OPD record file room, as we headed for General Handy’s office. Bond was leading and took the inside as she made the left turn onto the E-Ring, only to run full force into Stilwell, knocking him to the ground. Stilwell, from a sitting position on the hall floor, looked up at Bond and snorted, “First time I ever came 6,000 miles to be knocked on my ass by a warrant officer!” With that he arose, brushed himself off, and continued down the hall.

Regardless of our high security clearance, we were never allowed to enter the code room, for it contained the new SIGABA code machines. These highly classified devices were somewhat akin to the German Enigma machines and were stringently guarded—except in one unfortunate instance that I witnessed from a distance.

The U.S. Army had some sort of large Signal Corps operation in a South American country, possibly Brazil, and for some unknown reason a senior U.S. officer stationed in that facility started to take a party of foreign officers into the code room there. An alert sergeant immediately ordered all the covers to the machines to be lowered, closing them to view. But news of the event soon made its way back to Washington and Marshall’s desk.

A scathing message went out, reducing the officer from his elevated wartime rank to his Regular Army prewar rank and directing him to report to Washington immediately. I never heard the final consequences, but I am sure they were very severe. Interestingly enough, later in the war a truck containing a full SIGABA unit being readied for movement disappeared. Apparently taken by some GIs going AWOL, the truck was ditched in a river and recovered several days later after a frantic search.

Two other messages stand out in my memory. One of these came from General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s headquarters in North Africa about the time of the Sicily invasion. It was directed as Eyes Only to General Henry “Hap” Arnold, chief of staff of the Army Air Forces. It concerned the all-black fighter group from Tuskeegee and was obviously in reply to an inquiry as to the unit’s efficiency. The bottom line, the report said, was that the unit was well trained but the pilots lacked the initiative to close with German fighters. For that reason the unit had been assigned to ground support. But, according to postwar accounts, this decision was apparently changed and the unit restored to full combat duty with fine results.

The second memorable message came from General Douglas MacArthur. We underlings always also enjoyed his personal messages with their flowery prose. In this instance, there was the usual distinctive MacArthur description of how a group of Japanese fighters had attacked a U.S. bombing force protected by a normal fighter cover. At the time of the attack, the air cover was being replaced—thus doubling the defense. The attack was a disaster for the Japanese, he said.

I do not recall why I was carrying the message to Marshall’s office, but I entered a full office and delivered the message. As I stood awaiting dismissal or reply, Marshall read the contents. He then remarked to the several senior officers present how much he admired MacArthur’s ability, commenting that—and I think these were his exact words—“General MacArthur knows what the Jap is going to do before the Jap knows it himself.”

Stilwell’s feelings toward the British came visibly to light one night in a message describing his first encounter with British Field Marshall Sir Harold Alexander. He commented on Alexander’s long nose and rather brusque manner, and Stilwell saw Alexander’s opinion of him as being one of astonishment—that a mere American could be in command of Chinese troops. He felt Alexander’s opinion was probably best expressed in the British term of “Extrawdinery!”

OPD was not a large agency by old General Staff standards. The front office included General Handy and two full colonels, Charles K. Gailey and Godwin W. Ordway, two sergeants, and two civilian female typists. The agency itself consisted of small staff sections known by the area for which they were responsible—for example, China-Burma, Africa-Middle East, ETO. Each was headed by a senior colonel with a small supporting staff. In my view, all were brilliant men, and many became general officers in field commands before the war ended.

Our immediate message center boss was a fairly senior lieutenant colonel, but somehow he wangled a right to observe the initial assault wave in the attack on Salerno, Italy. When he returned some weeks later we asked him about his experiences in the attack, believing him to be full of hair-raising tales. He replied that he did not see much as most of the time he had his pants down. He had been stricken with a violent case of the GIs, a fate that apparently afflicted a number of those in the assault wave. He described his actions as being four steps forward and squatting, four more and squatting!

The front office was manned daily, including Sundays, by the two colonels and staff, as were the various area offices. During the times when General Handy was present, no one was allowed to pass into his office without the verbal okay of Colonel Gailey, who, in my opinion, was perhaps the most imperious, authoritative, and ruthless man I ever met. How he survived in the service, I never understood, but he eventually rose to general officer rank. His deputy, Colonel Ordway, I found to be less than brilliant and obviously had to struggle with Gailey. I witnessed one instance of Gailey’s unwarranted behavior in which he attempted to foist responsibility for his own mistake onto the shoulders of a message center officer and Colonel Ordway.

It was discovered that a message that should not have been sent had been dispatched. The message center officer had been summoned to the front office, where he had received the message properly initialed in red by Gailey for dispatch. It was about 15 minutes later when Gailey learned it had been sent and flew into a rage, accusing Ordway of unauthorized dispatch. He then summoned the message center officer, blaming him as well. But here Gailey met his match.

The officer was a 40-year-old former Reserve captain, who had been deemed too old for line duty. He had been a successful businessman and had volunteered for active duty. He was not about to take the unwarranted accusation. The officer turned and headed back to the file section, returned with the properly initialed cover sheet, and dumped it on Gailey’s desk. Gailey quickly saw his initials, threw the paper on his desk, and turned to other matters without issuing any sort of apology. I can add that Gailey inflicted a similar act on this writer, who was too young and inexperienced to rebut the man and ended up transferred. I realized in later years that I could have demanded a formal inquiry and pinned Gailey’s hide to the wall.

A sergeant told me about another unwarranted Gaileyism he observed that occurred a year before I arrived. According to the witness, an Army Air Forces lieutenant colonel entered the front office and said he was sent to see General Handy, apparently by General Arnold. But Gailey merely waved his hand at the officer and told him to take a seat although General Handy had no one in his office at the time.

Almost an hour passed, and the officer arose and left. It was a year or more later, the sergeant said, when that same officer returned again to General Handy’s office, this time wearing the silver star of a brigadier general and saying something to the effect, “Colonel Gailey, I am here to see General Handy, and I do not intend to sit on that couch for an hour!”

According to the sergeant, Gailey looked up, recognized the man as well as his rank, and immediately led him into General Handy’s office without a word.

I had the opportunity toward the end of my tour to make the brief acquaintance of Lord Louis Mountbatten, commander of Allied forces in the China-Burma-India Theater and to encounter for the first time a very characteristic piece of the British Army uniform. Again, it was while I was headed up the ninth corridor toward the E-Ring and General Handy’s office that I heard a most unusually loud clack-clacking. As I turned the corner, I almost ran into Lord Louis. He was wearing the issue type of British hobnailed boots. A polite “excuse me” came from the Britisher, who then clacked his way on down the E-Ring.

One last memory of my OPD days is a tale often heard about the office. General Marshall’s deputy, General Joseph McNarney, was a U.S. Army Air Forces officer serving as Marshall’s deputy. It was the belief that he often sat in on the very high level meetings with the Combined Chiefs of Staff—the joint sessions with the British staff in Washington and Marshall’s office. In these sessions, he supposedly acted as Marshall’s hatchet man. As such, he acquired the nickname of “Jumpin’ Joe” McNarney, the individual who jumped up and took strong issue when contentious points or subjects were brought up. Marshall thus retained his dignified composure, but the U.S. position was strongly presented.

It was in OPD that I learned to drink coffee. One of my fellow message center officers was a Cajun captain from Louisiana. Like the officer who had rebuffed Gailey, this officer was a volunteer and deemed to be too old for active field command as a captain. But he brought to the little office a Cajun ritual of coffee making. His untensils were a very small tin coffee pot in two parts.

He carefully inserted a piece of clean cheesecloth in the upper part. This was then filled with a carefully measured amount of very dark coffee that he had sent to him periodically from his home in Bastrop, Louisiana. Later, I learned it was laced with chicory. What emerged after boiling water had been poured through was a heavy black coffee strong enough for a spoon to stand in it. But we learned to stomach it by diluting it with generous amounts of condensed milk and heavy doses of sugar. I soon became addicted to strong coffee, and the habit continues to this day.

Now in my elderly years, I look back with fond memories of my time with OPD—except for the memories of Colonel Gailey.

U.S. Army veteran L. VanLoan Naisawald is a writer and historian who resides in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments