By Mark Simmons

Vice Admiral Norman Denning said of Ian Fleming, the “ideas man” who worked at British Naval Intelligence, that a lot of his proposals “were just plain crazy.” Yet “a lot of his far-fetched ideas had just the glimmer of possibility in them that made you think twice before you threw them in the wastepaper basket.” One that was not thrown out was the creation of what became known as 30 Assault Unit, or 30AU.

Director of Naval Intelligence Admiral John Godfrey and his assistant Commander Ian Fleming had been impressed by the exploits of Germany’s Abwehrkommando—a specialist unit formed mainly from the Brandenburg Lehr Regiment that moved with the advance of German troops using their linguistic skills. Many had lived abroad before the war, and they were able to seize anything of use in the intelligence field. They had achieved good results in the Balkans, Greece, and Crete.

The idea to form a similar, if expanded, specialist unit of Royal Marine Commandos was put before the Joint Intelligence Board in 1942, which agreed to the formation of the unit. Initially, it was to be divided into four troops of Royal Marines, Army, Royal Air Force, and Royal Navy (the RAF troop was never formed).

The Royal Marine 33 Troop of the yet to be designated 30AU took part in the ill-fated Dieppe raid in August 1942, as a clandestine part of 40RM Commando. Their goal was to obtain a cipher machine and documents from the German naval headquarters housed in a quayside hotel.

Ian Fleming had wanted to go in with them but was deemed too much of a security risk if captured, so he watched the landings from the deck of the destroyer HMS Fernie, a mile off shore. The RM troop consisted of two officers, two sergeants, three corporals, and 21 Marines. For this operation the unit was designated 10 Platoon, X Company, 40 Commando, which was transported to Dieppe on the old, flat-bottomed Yangtze River gunboat HMS Locust.

The Locust was captained by Commander Robert E.D. “Red” Ryder, a former polar explorer, who had won the Victoria Cross during the raid on Germany’s naval base at St. Nazaire, France, five months earlier to prevent the drydocks there from being used by German battleships.

The Locust came in toward the shore at 15 knots heading for the mole to land the Marines, but it was shrouded by thick, black smoke, and the gunboat was met with a blizzard of shellfire. One Marine, “Ginger” Northern, was killed before the men could get off Locust. Paul McGrath, 19 at the time and another Marine seeing his first action, recalled, “The noise of the explosion was gigantic. The shock of it blew all the fuses in my nervous system. I was petrified with such terror; it stunned my mind.”

In the face of such heavy fire, Ryder abandoned the run-in toward the mole; the Marine Commandos went over the side, down scrambling nets into landing craft, and a flotilla of them headed for the shore through a smoke screen. They emerged running onto the beach where the Canadians had landed and were stranded. Some of the landing craft got the message to abort the landing, shouted and waved by Lt. Col. J.P. Phillips, wearing a pair of white signaling gloves to be seen better.

The craft carrying 10 Platoon grounded on the beach and was immediately caught in a crossfire. Lieutenant Herbert Huntington-Whiteley, the platoon commander, ordered his men to abandon their kit and swim for it back to the ships.

Thus Fleming’s first experiment with this specialized unit ended with the men swimming away from the burning landing craft and the carnage on Dieppe beach. Sergeant John Kruthoffer swam for more than two miles before being picked up. Paul McGrath thought he was going to drown after his life jacket deflated; he wrestled to get his trousers off, often going under. Luckily, he was dragged into a small boat.

Of the 5,000 Canadian troops that landed at Dieppe that day, only 2,200 came back. Along with Marine Northern killed on Locust, Marine John Alexander from 10 Platoon lost his life. Their parent unit, 40 Commando, suffered a total of 99 officers and 23 men killed at Dieppe, the rest wounded or captured.

In his report, Fleming found it difficult “to add up the pros and cons of a bloody gallant affair,” but he thought the “machinery for producing further raids is thus tried and found good.”

The 30 Assault Unit then settled down to a period of training, including house clearing using the bombed houses at Battersea plus lessons on explosives, bomb making, and safe blowing. Marine McGrath recalled, “Lieutenant Curtis, who spoke perfect French, gave us some interesting French lessons.” The buzz was maybe they were going to France.

Admiral Godfrey had decided that a small section would take part in Operation Torch, the upcoming Allied invasion of North Africa. Commander Ryder had been appointed CO of the unit, which had now been given the cover name “Special Engineering Unit.”

Lieutenant Dunstan Curtis, Royal Navy, would command the first assignment; his detachment joined the cruiser HMS Sheffield on the Clyde. Also on board were 600 American troops. Training on the journey south—weapon handling, physical conditioning, and French lessons—continued.

After arriving at Gibraltar, the destination was revealed: Algiers in French North Africa. Once ashore, Curtis and his small team’s mission was to locate the French naval headquarters and grab whatever they could. For the landing, along with the American troops, they transferred to two destroyers, the Assault unit on HMS Malcolm.

In the early, moonless hours of November 8, 1942, both Royal Navy ships flew the Stars and Stripes as they headed toward the Bay of Algiers, hoping the French would not fire on them.

The plan soon went awry in the darkness. The ships could not find the narrow harbor entrance, and then the French woke up. The intruders were lit up by searchlights and came under fire from the shore batteries. Malcolm was closer in at that time, and her crowded decks were swept by shells and shrapnel; 10 men were killed and 25 wounded. McGrath had the feeling of “here we go again” but kept his head down, for on a ship “there is no hiding place.” The damaged ship headed out to sea.

The HMS Broke, the second destroyer, did at last find the boom, slipped into the harbor, and landed her embarked American troops. However, Broke also came under heavy fire and had to leave her moorings twice. Eventually, she left the harbor. Barely passing the boom, she was hit twice and was badly damaged; she would later sink.

The American troops, cut off and coming under increasing pressure, had to surrender. The members of 30AU transferred from the damaged Malcolm to HMS Bulolo, a converted liner and the command ship of the task force from which more American troops landed some 12 miles west of Algiers.

Having landed, they set off toward a secondary objective: the Italian Armistice Commission headquarters at Cheragard, seven kilometers away, where they took the headquarters housed in a villa and captured seven Italians. Later, in Algiers, Lieutenant Curtis found an Abwehr Enigma coding machine in the German Armistice Commission; it was hurried back to Bletchley Park, Britain’s top-secret decoding facility.

In addition, about two tons of documents were scooped up and flown to Gibraltar and then on to England. These finds completely justified 30AU—and Godfrey’s and Fleming’s faith in the unit.

The men returned from North Africa to find they had now been designated 30 Commando, and they had a new headquarters at Amersham, Buckinghamshire. They were reorganized into three troops: Naval, Military, and Technical—the later composed of RNVR officers, specialists in mines and torpedoes, submarines, radar, and secret documents.

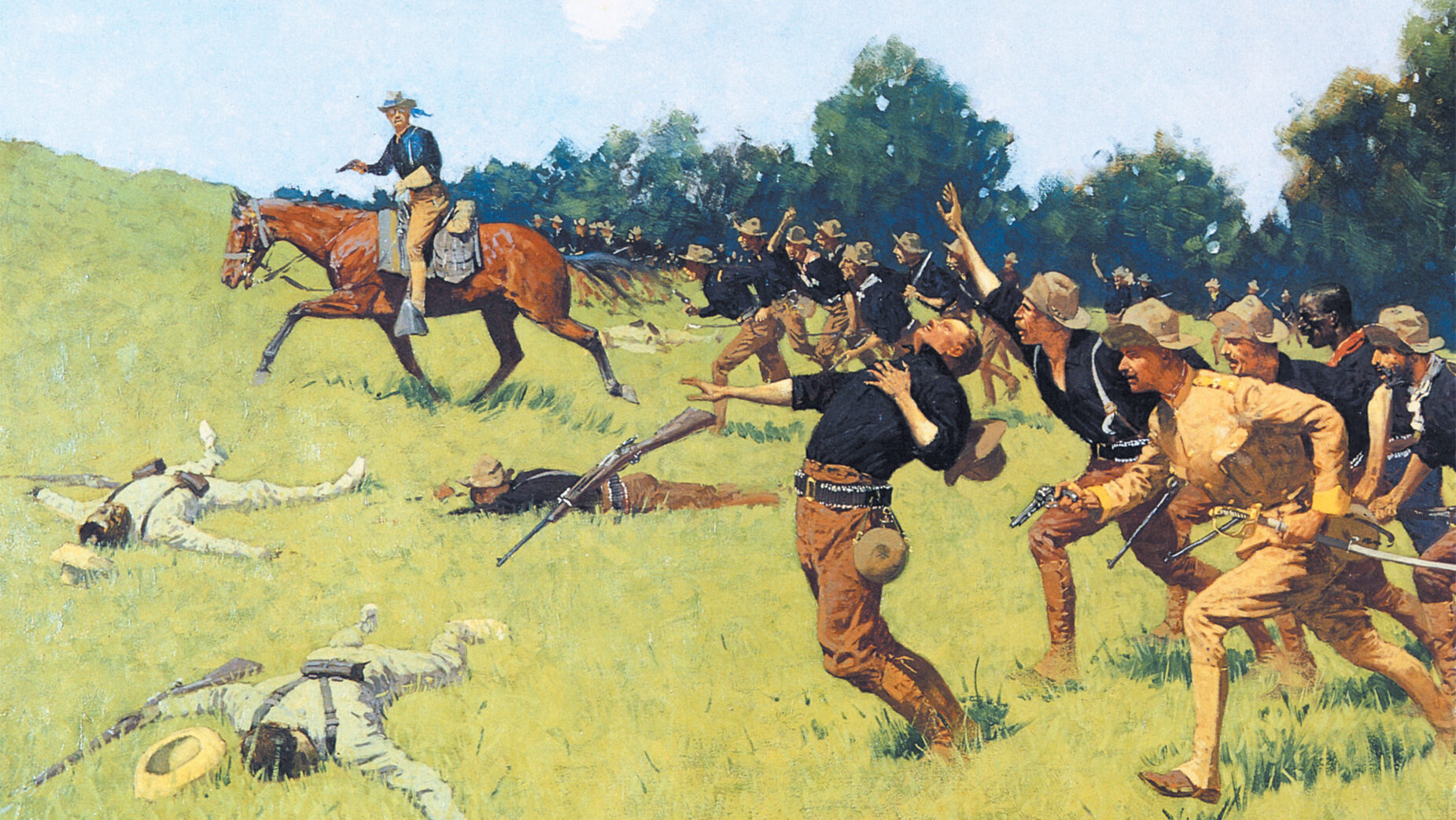

The next big mission for 30AU was Operation Husky—the invasion of Sicily. On July 9-10, 1943, they landed on the island near Cape Passero along with the British Eighth Army’s XXX Corps, under General Bernard L. Montgomery. One of their first objectives was the German coastal radar.

After overcoming the German machine-gun positions guarding the coastwatcher installation, and assisted by 20mm Oerlikons firing from their LST plus their own small arms, they found no wounded or any survivors. But many of the station’s Kriegsmarine crew had been killed. Unfortunately, the radar set had also been destroyed. However, radar manuals were found on the body of a German naval lieutenant.

Lieutenant Commander Jim “Sancho” Glanville recalled, “We also found a copy of the handbook of the Telefunken T39 series of radar sets, designated the ‘Würzburg,’ and including the ‘firebowl’ for fighter and anti-aircraft gun control.”

Farther along the coast, another section captured an Italian RDF station where ciphers used by the Italian Air Force homing beacons were obtained. These and other documents were hurried back to Malta where the RAF started using the homing beacons themselves.

In Augusta, Sicily, another Enigma machine and acoustic instruments were grabbed along with Italian naval documents hidden in the caves at Melilli, where a cache of sea mines was also discovered. The 30AU had become a law unto themselves and, after some Marines took a fire engine and converted it for their own use, Major Humphrey Quill, Royal Marines, who commanded a detachment on Sicily, was summoned to Malta to explain their actions to Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the commander-in-chief.

However, the unit kept securing important finds. In the naval base at Trapani, Glanville and his Marines captured the stores and maintenance departments intact. Marine K.A. “Jock” Finlayson helped Lt. Cmdr. Lincoln defuse dozens of sea mines. “All afternoon I was assisting him getting bits off, and quite petrified, my vivid imagination expecting booby-traps or time pencils blowing us and Trapani sky high,” Finlayson said.

After Sicily came the invasion of mainland Italy. The 30AU landed at Salerno on September 9, but by the time they reached the enemy’s naval headquarters they found it had already been destroyed along with all the documents. Three days later, after receiving reports of enemy radio signals coming from Capri, a section landed on the island. They were met by the town band at Marina Grande playing “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.”

Lieutenant Commander Quintin T.P.M. Riley led this detachment; Glanville was his second in command, and there were 15 other ranks. They found out from the mayor (who wore “a grey top hat” and Glanville thought looked like “a character in Alice in Wonderland”) that there was a force of 36 Italian soldiers holding a fort in the central town of Anacapri. Commandeering a truck the next day, the commandos made their way to the town early in the morning and took the garrison by surprise; again a wealth of material was obtained.

The unit was also engaged in various operations around the Bay of Naples. In a night raid right under the noses of the Germans, they removed the Italian Admiral Eugenio Minisini and his wife from the torpedo works on the Baia Peninsula and took the couple to Capri. There the admiral was interrogated and supplied a great deal of information on the whereabouts of documents on torpedo and submarine research.

John Steinbeck, then a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, sent a dispatch dated October 15, 1943, titled “The Lady Packs,” recording his impressions of the “celebrated commandos” whom he found to be “very strange men.” Wearing boots “with thick rubber soles, which looked far too large for them. They were dressed in faded shorts and open shirts, and their arms were an old-fashioned revolver, and a long wicked knife each.”

It seems Steinbeck got mixed up between operations, for the rescue of Admiral Minisini took place with a LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) towing a whaler to ensure a silent landing, whereas he cites an MTB (motor torpedo boat). And the commandos had no trouble that night but he indicates they disposed of eight guards with their wicked “long, thin knifes.”

Another sub unit, 34 Army Troop, took part in the ill-fated Leros campaign in the eatern Mediterranean. On October 5, 1943, Captain Tom Belcher of the Staffordshire Regiment and four other men were killed when they were bombed by enemy aircraft. By now the focus had shifted to France and the expected invasion, but 30AU would maintain a small unit in Italy as the Allies advanced north.

There was a power struggle now over who should control the unit and what it should become. Colonel Robert Neville of Combined Operations had gone to Italy to inspect 30AU and expressed the opinion the unit should become part of the Royal Marines. Fleming argued it never was or had been intended to be a commando unit. It was too small, rarely exceeding 120 men, whereas a commando unit was around 600 men. Its task was intelligence gathering in which it had excelled and should be part of the Naval Intelligence Division.

Fleming won the argument. It was reorganized into three troops and redesignated A, B, and X, with its new base at Littlehampton on the south coast. All the fighting men were now Royal Marines, and the new commander was Lt. Col. Arthur Woolley, RM; the intelligence gatherers were mainly RNVR officers.

The 30AU became part of Naval Intelligence as NID30, with its own office at the Admiralty. After his return from Italy, Lt. Cmdr. Glanville recalled being told by Fleming that the unit needed to shape up: “You can’t behave like ‘Red Indians’ anymore. You have to learn to be a respected and disciplined unit.” But the desk-bound Fleming liked to hear the stories of their adventures—some of which would find their way into the James Bond books.

The Channel-crossing phase of the Normandy invasion, code named “Neptune,” was a huge undertaking, with 30AU, which was split into three sections, playing only a tiny part. The first 30AU group to land on Juno Beach was X Troop led by Captain Geoff Pike, RM, with their target the radar station at Douvres-la-Delivrande. Second to land was “Curtforce,” led by Dunstan Curtis with 21 men; they landed on Gold Beach on D+1. The main body, under Lt. Col. Woolley, landed on Utah Beach on D+4, their target being Cherbourg.

At 8:35 am on June 6, X Troop was ashore on the Nan Red sector of Juno Beach. On the run-in to the beach, Captain Pike wondered about his “capacity to take it, knowing half my troops had been under fire and I had not.” Jim Glanville was beside him, and Pike was heartened by his cool demeanor: “He never seemed to be frightened—just interested in what was going on.”

Their landing went well, with water only coming up to their knees as they raced through the surf to the nearest cover under the promenade along the front. The unit next to them on the left, 48 Commando, was attracting all the fire.

The 30AU moved off the beach at 9:45 am without losing a man. X Troop spent most of that first night in some German trenches before they arrived at the radar station; its 130-foot tower had been damaged by the naval bombardment, but much of the station was underground and protected by barbed wire and minefields. It was too hard a nut for the unit to crack alone.

Four days later, Lt. Cmdr. Patrick Dalzel-Job landed at Utah Beach with the main body. They found it difficult to move inland with their own vehicles past the masses of American troops, so an hour after dark they halted near Ste.-Mère-église for the night. There were no orders to dig in, but some men did. Almost all the aircraft they had seen that day were Allied, so they paid little attention when they heard aircraft low overhead.

“Suddenly, there was an explosion like a bomb-blast immediately above us,” Dalzel-Job said, “followed by a peculiar fluttering noise in the air. For a while nothing else happened; then the whole field was lit by sharp flashes and explosions, like heavy machine cannons firing sporadically around us. The explosions did not last more than half a minute. In that time, the unit lost 30 percent of its strength in killed and wounded.”

They had been hit by an early type of cluster bomb called a “butterfly bomb” because the grenade-size bombs fluttered down to land before exploding. The 30AU suffered three men killed and 21 wounded, some seriously.

Paul McGrath, now a sergeant, led a section that pushed 15 miles beyond the American bridgehead at Omaha Beach, looking for possible V-1 rocket launch sites; Flight Lieutenant David Nutting was the air technical officer who went with them. They found one site near Neuilly-la-Fôret. Dalzel-Job described it as having a “‘J’ concrete runway, and all around were scattered hurriedly abandoned German equipment and belongings.” The next day, the first of over 8,000 V-1 flying bombs that were launched before the end of the war were fired at London.

There were hundreds of German troops inside the Douvres-la-Delivrande radar station, and the siege lasted a week. They had been bombarded by naval guns and aircraft and field artillery, and the station finally fell after a textbook attack by 41 Commando.

By then there were only a handful of men from 30AU there under Lt. Cmdr. Glanville; most of X Troop had rejoined the main body. When he got into the station, Glanville was exasperated at the amount of looting that had gone on, with many of the culprits being officers. The haul was small—only some wheels from an Enigma machine and a used cryptographer’s pad.

Part of Curtforce—with Lieutenants Guy Postlethwait and Tony Hugill (both RNVR) and 19 Marines—had better luck. They had landed at D+2 at Arromanches before moving west toward Port-en-Bessin. On the way they overran a radar station and hit the jackpot. It was taken intact, with a top-secret listing of all German radar installations in northwestern Europe, along with all the technical data on wavelengths, polarization, pulse repetition frequency, and aerial display. Once back with the Admiralty, this trove was regarded as the most important radar intelligence seized during the war, and within 36 hours all German radar in that group had been jammed.

The 30AU were often right up with the forward troops in the advance, and for such a small unit they often achieved startling results by bluff and guile.

Such was the case with the radar station near Saint Pabu. French civilians told Tony Hugill that 1,500 Germans were there. After they went to take a look, Hugill decided to try and bluff them into surrendering by pretending that his was a bigger force. Given that the Germans were surrounded by a hostile population bent on revenge, they might be inclined to surrender to regular Allied troops.

Hugill, Sergeant McGrath, and Marine Sandy Powell went forward under a white flag; it was a 300-yard nervous walk out in the open to the station’s gates. The guards called for the commandant, a Luftwaffe officer, who was found after five minutes; he was accompanied by 10 armed guards and four officers. Hugill asked him in good German to surrender. He refused, not wanting to surrender to such a small force. Hugill shrugged his shoulders, saying he represented a larger force of Americans—not that it mattered much, as they would be calling for an air bombardment in less than half an hour.

Some firing started then. To stop it, McGrath climbed on top of a blockhouse, signaling a cease-fire. By the time the Americans arrived, the Germans had surrendered. Hugill was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and McGrath and Powell Distinguished Service Medals.

While bold, this approach was risky. On September 12, Herbert Huntington-Whiteley RM, by then a captain, was killed at Le Havre while trying to talk the Germans into surrendering under a white flag. Along with the German officers, he was gunned down by some hard-line Nazis. He was 24 and had led the first AU troop at Dieppe, and in May 1944 he had received a mention in dispatches for “good services in the Mediterranean.”

By the time of the final push into Germany, 30AU had grown to 25 officers—half of whom were Royal Navy—and up to 300 men, mostly Royal Marines. They worked largely in teams of 30 with eight vehicles. They were among the first Allied troops to cross the Rhine. Colonel Humphrey Quill now commanded the unit.

Ian Fleming had drawn up a list of objectives, one of the main ones being the advanced U-boats built and designed at Kiel; 30AU were the first Allied troops to enter the port city. Much evidence was found about the fast type XVII U-boats known as “Walterboats,” named after the hydrogen peroxide drive system designed by Dr. Hellmuth Walter.

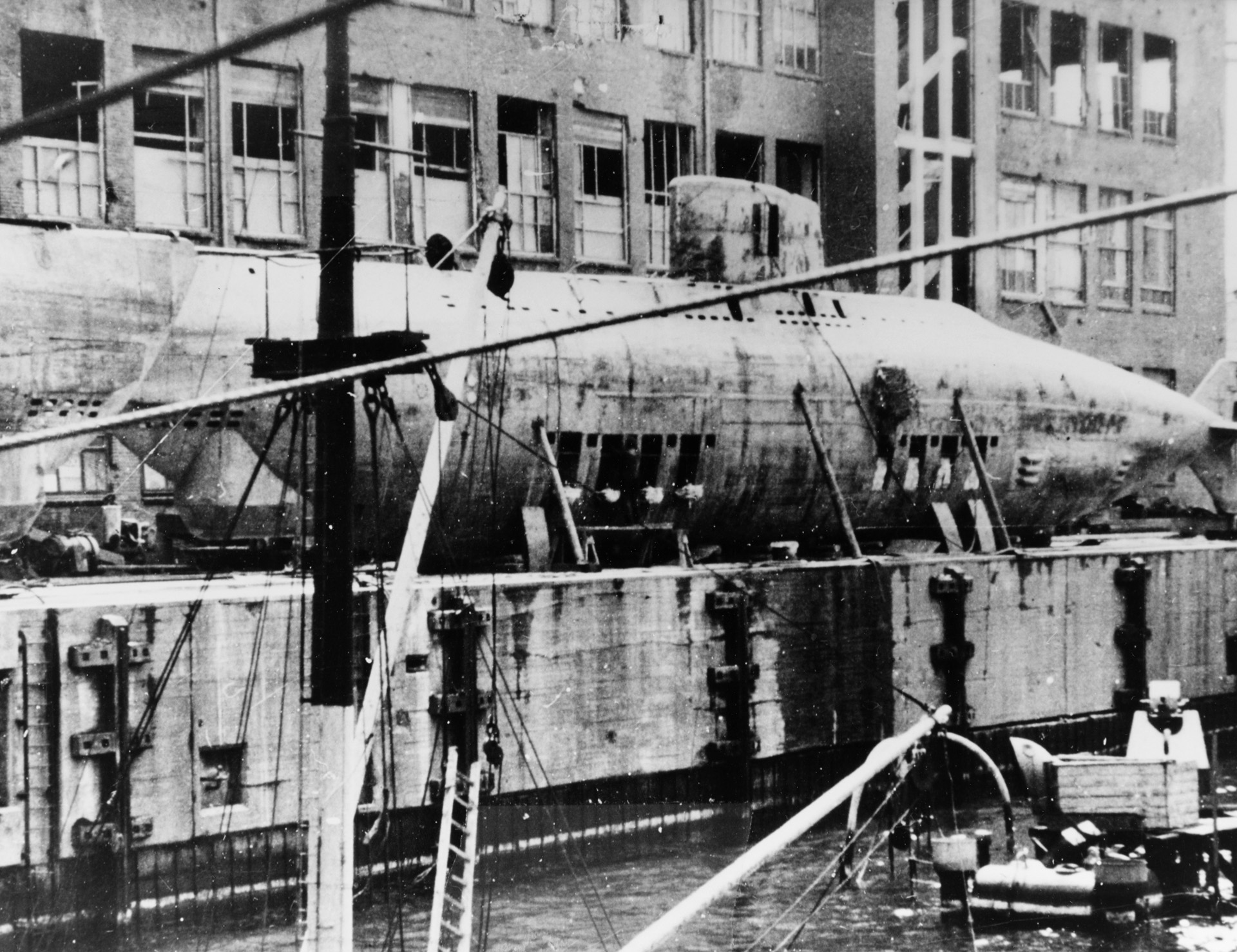

In Hamburg, I.G. Aulen, known as “Jan”—then a commander serving with 30AU—came across two of the “Walterboats” that had been heavily damaged by bombs lying on the jetty. They resembled “a gigantic fish rather than a conventional submarine … an immediate clue to unusual speed.” However, on closer inspection it was found that many of the more vital parts had been removed.

In Kiel, Dr. Walter was captured. He would reveal nothing and confessed to being a loyal Nazi. Colonel Quill rushed off to Admiral Karl Dönitz’s headquarters, where he obtained written orders from the admiral, the last leader of the Third Reich, that nothing was to be withheld from 30AU. Walter then cooperated fully, getting submarine tests, various torpedoes, aircraft jet engines, and -1 launch ramps ready to demonstrate for Allied VIPs.

Also on Fleming’s list was the German one-man submarine. Admiral Bertram Ramsay, who by then had 30AU within his overall command, doubted such a vessel existed. Commander Ralph Izzard found one washed up near Walcheren. He put it on a tank transporter and took it to Ramsay’s headquarters.

Upon seeing it, the admiral still had reservations that it would ever be used, dismissing it as just “a toy.” Izzard suggested he look down the periscope, which he did, only to be met by the gaze of a dead German’s eyes in his bloated corpse at the other end, encased in his steel tomb.

With the items on Fleming’s black list nearly fulfilled, he got in on the hunt himself. Jim Glanville had come across evidence of the German Naval Intelligence archives that were located in the Tambach castle in the Bavarian Alps and, with a small team, he set out to find them.

The journey was difficult because of damaged bridges and wrecked roads. “The whole area was in a state of chaos,” Fleming wrote, “with SS units fighting it out, Wehrmacht fighting or surrendering, and with bands of escaped POWs, mainly Russians and Poles, roaming the countryside, or deserters from the German Army.”

Reaching the castle they were confronted by a German sailor who surrendered when challenged by a Marine’s tommy gun. World War I veteran Admiral Walter Gladisch commanded the post, and he was delighted to see Glanville and his men. He had been ordered by Dönitz to hand over the archives to the Allies. He had doubted his ability to comply because of SS bands nearby and even some of his own staff who wanted to destroy the records.

Concerned about the fate of the records, Fleming arrived at the castle, which he described as “Cold. Dismal. Comfortless. Ghastly. Count Dracula stuff,” although he found the old admiral “quite helpful.”

The entire archives were brought in a convoy of three-ton trucks to Hamburg, from where they were loaded onto a fishery protection trawler for the voyage to London. Later, Fleming admitted he enjoyed his trip to Germany. With the war almost over, he felt that his creation, 30AU, when compared to others serving at the front, had “enjoyed a far more light-hearted war,” although the unit in its “sharper moments had lost too many men,” which he bitterly regretted.

In 1946, 30AU was disbanded. In 2010, the Royal Marines formed “30 Commando Information Exploitation Group,” which carries the history of 30 Assault Unit. Three years later, 30 Commando IEX was granted the “Freedom of Littlehampton” in honor of the original unit being based in the town. Such a distinction is an ancient honor granted to military organizations that allows them the privilege of marching into a city “with drums beating, colors flying, and bayonets fixed.”

Many of the exploits and adventures of 30AU would find their way into Fleming’s 007 books, starting with the first, Casino Royale, in 1953.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments