By Christopher Miskimon

On May 27, 1905, the Russian fleet went into battle against the Japanese navy. For months, this fleet sailed around the world, beginning its long journey in the Baltic Sea. The Russo-Japanese War was in full fury, and the Russian navy had fared poorly in prior battles, so the Russian government had dispatched the new Second Pacific Squadron. This new squadron, commanded by Admiral Zinovi Rozhestvensky, sailed to avenge previous Russian defeats and sweep the upstart Japanese navy from the seas.

The journey from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean proved both physically and mentally demanding. Many of the aged ships proved prone to mechanical breakdown. Few experienced seamen sailed with the fleet; most of the Russian Navy’s veterans were already serving in the Pacific, lay dead, or sat in prison camps from previous battles. Many of the new sailors came from farms or factories and had no experiences of the sea. Even worse for the Russian officers, some were revolutionaries, angry over Russia’s almost-feudal political system. The Russians being belligerents in an ongoing war, most nations denied them the use of their ports, making the necessary frequent stops to replenish coal even more difficult.

Despite incompetence, unreliable ships, rebellious crewmen and limited assistance, Rozhestvensky got his fleet around the world and in position to fight the Japanese. Even without combat, it was a tremendous feat of seamanship and showed him an effective leader of Russian sailors. Still, many of the ships were worn from the journey, and all of them desperately needed time in drydock to have their hulls scraped and cleaned. Japanese Admiral Togo used the time to refit his ships as they awaited the approaching enemy fleet, even as some Russian ships began posing a threat in the Pacific.

The battle of Tsushima proved a testament to the bravery of the Russian crews; yet at the same time, it revealed glaring shortcomings in their fighting capabilities. Russian gunnery compared poorly to that of the Japanese, although they inflicted some damage with their armor-piercing shells. In contrast, the Japanese skillfully employed new explosive incendiary ammunition, which wrecked the top decks and superstructures of the Russian ships, causing extensive casualties and igniting fires. Japanese torpedo boats also inflicted damage on the Russian fleet, making repeated sorties around the clock.

In the end, the Russian fleet suffered yet another defeat. The loss proved to be humiliating not only for the empire, but also for Tzar Nicholas II personally, who bore a grudge against Japan for an attack by a crazed samurai he had suffered decades earlier during a visit there. In the first years of the 20th Century, Japan was not yet taken seriously by the West. Success in the Russo-Japanese War was Japan’s first step toward proving its capabilities to the world. It also boosted the Japanese Empire’s confidence and fueled the empire’s aggressive nature.

In the end, the Russian fleet suffered yet another defeat. The loss proved to be humiliating not only for the empire, but also for Tzar Nicholas II personally, who bore a grudge against Japan for an attack by a crazed samurai he had suffered decades earlier during a visit there. In the first years of the 20th Century, Japan was not yet taken seriously by the West. Success in the Russo-Japanese War was Japan’s first step toward proving its capabilities to the world. It also boosted the Japanese Empire’s confidence and fueled the empire’s aggressive nature.

The historical events that led to the meeting of these two great fleets is well told in The Battle of Tsushima (Phil Carradice, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2020, 184 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, $32.95, hardcover).

Tsushima’s effects proved as wide-ranging as the actions that led to the battle itself. The author covers both, providing much more than a simple retelling of the fight and its immediate aftermath. The book begins by revealing the cause of the tsar’s prejudice against Japan and establishes the background through the inclusion of world events, Japan’s ambitions, and the machinations of the Russian royal court. The Russian fleet’s epic journey reads as a combined endurance test, challenge of international diplomacy, and tactical problem. The drama builds as Rozhestvensky makes his way to the Pacific with Togo waiting. Overall, the book effectively explains the Battle of Tsushima, largely forgotten by history but one of the most significant engagements of the early 20th Century—one that heavily influenced the coming world wars.

The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906: The True and Tragic Story of a Black Battalion’s Wrongful Disgrace and Ultimate Redemption (William Baker, USA (Ret.), Cranberry Twp, PA, 2020, 481 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover)

The Brownsville Texas Incident of 1906: The True and Tragic Story of a Black Battalion’s Wrongful Disgrace and Ultimate Redemption (William Baker, USA (Ret.), Cranberry Twp, PA, 2020, 481 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $30.00, hardcover)

In the early 20th Century, Brownsville, Texas, was situated near Fort Brown, the home station of the 1st Battalion, 25th Infantry Regiment, a unit composed of African American troops led by white officers. The citizens of the town became incensed on August 12 over a reported attack on a white woman and blamed the black soldiers. In response, the unit’s officers ordered an early curfew to keep the soldiers apart from the townspeople.

On the night of August 13, gunfire erupted, and a white bartender and a police officer were shot. The black soldiers received the blame, despite evidence they were not involved. Townspeople provided shell casings in the caliber of army rifles, but the soldier’s rifles were checked after the shooting and had not been fired. Despite the lack of real evidence, President Theodore Roosevelt summarily discharged 167 of the unit’s men without trial. It was not until 1972 that a new investigation corrected the long-standing injustice.

Lt. Col. William Baker worked in the Pentagon at the time and reinvestigated the incident for the army. The case he prepared led to the restoration of the discharged men’s rank and honor. This book is Baker’s account. It is not only a tale of racism and unfair treatment, but also one of justice and redemption. It contains a well-written, detailed narrative that lays bare the injustice that occurred and its belated correction.

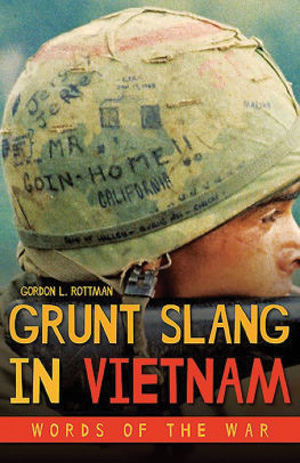

Grunt Slang in Vietnam: Words of the War (Gordon L. Rottman, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2020, 240 pp., appendices, bibliography, $34.95, hardcover)

Grunt Slang in Vietnam: Words of the War (Gordon L. Rottman, Casemate Books, Havertown PA, 2020, 240 pp., appendices, bibliography, $34.95, hardcover)

Soldiers in the Vietnam War used a variety of slang terms. A soldier with his hands in his pockets was said to be wearing “Air Force gloves.” Marines called the same infraction “Army gloves.” Chaplains passed out “sympathy chits” to complaining soldiers. A “million-dollar wound” was one serious enough to send you back to America but not so severe as to be crippling.

Some terms even endure to the present day. For example, “Helo,” “birth-control glasses,” and “Mark One Eyeball” are all terms still recognizable to current service members. Other terms have fallen into disuse and are no longer part of military lexicon. Whatever the case, the slang of the U.S. military in Vietnam is descriptive, humorous, and witty.

The author is a Vietnam veteran and has first-hand knowledge of his subject matter. Organized alphabetically, each entry contains a detailed definition complete with background information on the term’s origin. A set of appendices provides examples of the Pidgin English used by Vietnamese during the war, unit and equipment nicknames, and military ranks.

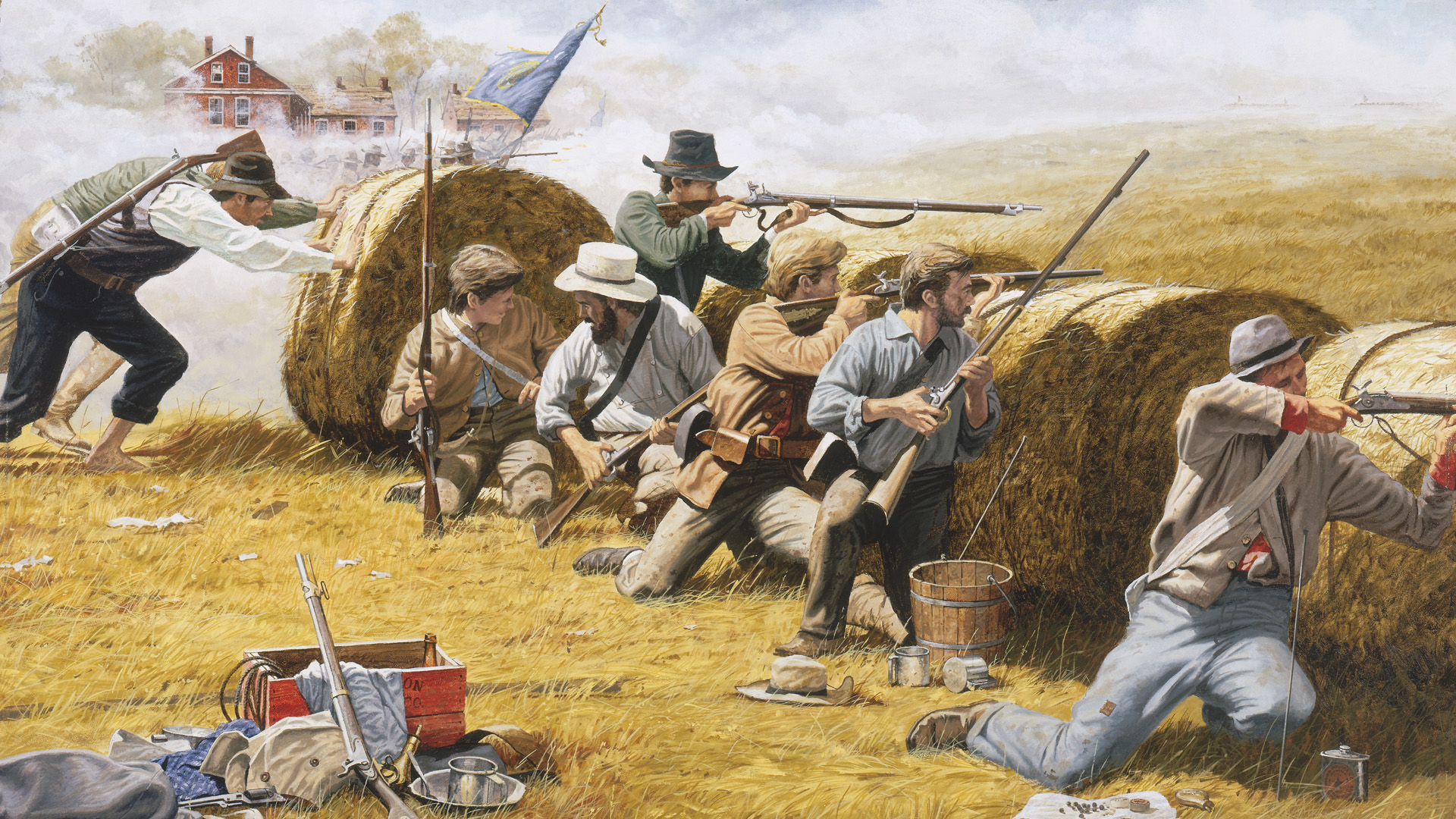

American Amphibious Warfare: The Roots of Tradition to 1865 (Gary J. Ohls, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2019, 274 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

American Amphibious Warfare: The Roots of Tradition to 1865 (Gary J. Ohls, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2019, 274 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

The overland route to Mexico City posed great problems for Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor as he sought to prosecute the war with Mexico to a successful conclusion. Although he won every battle in the northern part of the country, Taylor realized those victories would not bring the Mexican leadership to terms. The Americans had to capture Mexico City, but the marching route was long and the terrain difficult. The answer lay in Veracruz, a coastal city already under blockade by the U.S. Navy. Beaches near the city led to routes that would enable American forces to march straight into the heart of Mexico. An amphibious landing proved the key to Mexico’s defeat.

The amphibious assaults of World War II are most familiar to modern readers, but they were built upon a tradition of sea-based landings going back to the American Revolution. This new book gathers seven examples of amphibious operations through to the Civil War, laying out their connection and importance to the larger conflict. This new work, which offers insightful analysis in addition to narrative history, provides a clear understanding of the American military’s use of amphibious warfare.

The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman (Brian Holden Reid, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, 2020, 632 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

The Scourge of War: The Life of William Tecumseh Sherman (Brian Holden Reid, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK, 2020, 632 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

At first glance, there seemed little to predict William T. Sherman would become one of America’s greatest generals. He did not see combat in the Mexican American War, which almost all other Civil War leaders who attained high rank had experienced. As a civilian before the war, Sherman’s business venture saw little success. Early in the conflict, a mental breakdown seemed to portend failure and obscurity. But Sherman recovered and went on to win major victories. His reputation waxed as that of some better-known Union generals waned. His expertise as a military strategist and willingness to wage total war led to Sherman being regarded as one of the first practitioners of modern warfare.

Biographies of Civil War generals abound; however, this one is a worthy addition due to its clear prose, detailed research, and the effective arguments contained in the narrative. The author is an award-winning historian who has written a number of works on the American Civil War and its leaders. This latest scholarly work will add to his reputation.

Ia Drang 1965: The Struggle for Vietnam’s Pleiku Province (J.P. Harris and J. Kenneth Eward, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2020, 96 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $24.00, softcover)

Ia Drang 1965: The Struggle for Vietnam’s Pleiku Province (J.P. Harris and J. Kenneth Eward, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2020, 96 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $24.00, softcover)

The campaign in Pleiku Province began with a North Vietnamese Army attack on the American Special Forces camp at Plei Me. When the communist forces retreated from that effort, airborne troops of the 1st Cavalry Division gave chase in a bid to destroy them.

The resulting encounter was the famous battle at landing zone X-Ray, in which Colonel Harold Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, fought a difficult three-day, pitched battle against the North Vietnamese. Moore succeeded in defeating the North Vietnamese in that engagement, but a second clash at LZ Albany was a bloody affair where 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry was left holding the field, but only at a heavy cost. This campaign signaled that the war would not be easy or quick and revealed the skill and determination of both sides.

This book is among the latest in Osprey’s Campaign series, which examines important battles and operations throughout history. This work is number 345 in that series, which attests to its success. The book is well-illustrated with period photographs and original artwork along with excellent maps. It is a good choice for a reader seeking a concise yet thorough recounting of the campaign.

Gods of War: History’s Greatest Military Rivals (James Lacey and William-son Murray, Random House, New York NY, 2020, 384 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $32.00, hardcover)

Gods of War: History’s Greatest Military Rivals (James Lacey and William-son Murray, Random House, New York NY, 2020, 384 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $32.00, hardcover)

Military rivalries normally happen by coincidence. It takes a number of otherwise-unrelated decisions, orders, and opportunities to bring two particular and opposing leaders into contact on the battlefield. In the right circumstances, however, these meetings create legends and turn the tide of history. General George Patton and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel fought only because the American general’s predecessor had to be relieved for ineptitude. This gave the aggressive and flamboyant Patton the chance to face the vaunted Rommel in the rough terrain of Tunisia.

Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, whose names are synonymous with the American Civil War, served in the same army before the conflict. Various choices and happenstances placed them on the path to battlefield conflict. While Lee is often considered the superior general, Grant’s leadership won the war and changed history for the United States.

Likewise, Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompeius were former allies until ambition and lust for power brought them into opposition. The outcome of their fight helped transform a republic to an empire and changed the course of world history.

These are just three of the six case studies of warfare’s most famous rivalries in this new work. Each chapter covers their battles and provides a study of what made these leaders the formidable generals they were. The authors succeed in breathing new life into their narrative despite the well-known nature of their subjects. The book is fast paced, with a scope ranging from grand strategy down to battlefield decisions.

The War Queens: Extraordinary Women Who Ruled the Battlefield (Jonathan W. Jordan and Emily Anne Jordan, Diversion Books, New York NY, 2020, 368 pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, index, $27.99, hardcover)

The War Queens: Extraordinary Women Who Ruled the Battlefield (Jonathan W. Jordan and Emily Anne Jordan, Diversion Books, New York NY, 2020, 368 pp., maps, photographs, notes bibliography, index, $27.99, hardcover)

Massagatae warriors of Central Asia struck fear into the hearts of their enemies. Mounted archers and lancers served as an advance guard that softened up the enemy for the main body of infantry, which followed with spears and axes to finish the job. Queen Tomyris, who led these warriors, was clever and prudent.

The Massagatae lands bordered the eastern frontier of the Persian Empire, which was ruled at the time by King Cyrus II “The Great,” so she carefully kept on her side of the Araxes River, unwilling to provoke the aggressive Persians. In 530 B.C. Cyrus massed an army on the river. Tomyris baited Cyrus into crossing the river by issuing a challenge. The two armies fought a brutal battle, tearing at each other without finesse or tactics. The Massagatae won, slaughtering thousands of Persians, including Cyrus. Accounts differ as to his exact fate, but one story holds that Tomyris took the slain king’s head and dunked it into a skin filled with human blood, so that Cyrus might have his fill of what he came for when he invaded her lands.

This new book highlights history’s greatest female military leaders. From Tomyris to Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, each chapter relates how a woman took command during a time of military crisis and led her people. The narrative follows each subject through combat, strategy, and preparation, thus giving the reader insight into each leader’s style and capability.

Rome Rules the Waves: A Naval Staff’s Appreciation of Ancient Rome’s Maritime Strategy 300 BC – 500 CE (James J. Bloom, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2019, 282 PP., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $27.00, hardcover)

Rome Rules the Waves: A Naval Staff’s Appreciation of Ancient Rome’s Maritime Strategy 300 BC – 500 CE (James J. Bloom, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2019, 282 PP., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $27.00, hardcover)

Histories of ancient Rome generally focus on its land campaigns, and throughout its history Rome was mainly viewed as a land power. Indeed, it sent large armies of legionaries across Europe, Asia and North Africa. However, much of what the Romans accomplished, first as a republic and later as an empire, came through the deft use of naval power. With the Mediterranean Sea bordering the vast coastlines not only of Roman territory but also that of its enemies at various times in its history, a maritime strategy and a strong navy proved vital to maintaining Roman control and power.

The subject of this book is a difficult one given the relative dearth of available material, but the author’s work is innovative, parsing out the Roman naval role as it evolved over the centuries. He also covers the Roman Navy’s performance as a so-called silent service, giving vital support to the important land actions while receiving little credit or mention itself. The book effectively uses the information available to elucidate Rome’s maritime strategy.

Frederick the Great: A Military History (Dennis Showalter, Frontline Books, London UK, 2020, 384 pp., maps, bibliography, index, $50.00, hardcover)

Frederick the Great: A Military History (Dennis Showalter, Frontline Books, London UK, 2020, 384 pp., maps, bibliography, index, $50.00, hardcover)

Conflict drove early modern Europe. The leaders of the various nation-states saw warfare as a legitimate means of settling differences, avenging grievances, or exploiting opportunities. Even for national leaders, the stakes could be dangerously high. During that era, soldiers and citizens alike expected physical courage from their kings and generals. Prussian King Frederick II “The Great” was full of idiosyncrasies. He did not always live up to these martial standards, but he did lead his country forward into a time of greatness. Prussia militarism became so notable that many quipped it was actually an army with its own country. Frederick increased the size of his army, introduced new methods, and increased his artillery pool. He then used it to great advantage in the Silesian Wars and the Seven Years’ War.

This is a new edition of a classic work on Frederick the Great by the late Dennis Showalter, one of America’s foremost scholars on German military history. His work is detailed, thorough, and clear. Each assertion is supported using clear prose and complete annotation. The book provides a single-volume history of its subject, more than adequate to give the reader an in-depth understanding of Frederick at war and of the Europe in which he campaigned.

Images of War: United States Marine Corps in Vietnam (Michael Green, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2020, 205 pp., maps, photographs, $22.95, softcover)

Images of War: United States Marine Corps in Vietnam (Michael Green, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire UK, 2020, 205 pp., maps, photographs, $22.95, softcover)

The Marine Corps entered Vietnam with just 3,000 men on March 8, 1965. By 1968, the Corps had 86,000 Marines in the country. The last Marines in Vietnam were the embassy guards in Saigon who flew out on April 30, 1975. Between those years they fought countless battles and engagements on the ground and in the air.

This photobook graphically shows Marines serving in Vietnam in a variety of roles. The images are well-selected and interesting. There is also a color insert. Several sections of text are included and relate well to the photographs, all of which have detailed captions. A number of excellent maps place the imagery in the reader’s mind.

Short Bursts

“Vincere!” The Italian Royal Army’s Counterinsurgency Operations in Africa 1922-1940 (Federica Saini Fasanotti, Naval Institute Press, 2020, $44.00, hardcover). Italy fought against native guerillas in both Libya and Ethiopia. This book shows how the Italians adapted over two decades of warfare.

“Vincere!” The Italian Royal Army’s Counterinsurgency Operations in Africa 1922-1940 (Federica Saini Fasanotti, Naval Institute Press, 2020, $44.00, hardcover). Italy fought against native guerillas in both Libya and Ethiopia. This book shows how the Italians adapted over two decades of warfare.

Crusaders: The Epic History of the Wars for the Holy Lands (Dan Jones, Viking Press, 2020, $30.00, hardcover). The series of wars known as the Crusades were formative to the development of Europe, with far-reaching effects. This new work delves into this crucial period in history.

British Battle Tanks: Post-War Tanks 1946-2016 (Simon Dunstan, Osprey Publishing, 2020, $$30.00, hardcover). This is the last in a four-part series on British armor. It is well-illustrated, covering the development and use of these armored vehicles in numerous conflicts and the Cold War.

From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Gen. James Longstreet, edited by James I. Robertson, Jr., Indiana University Press, 2020, $75.00, hardcover). This is the memoir of the famed Confederate general who commanded the I Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. It is updated with notes from the editor.

The Wars of Alexander’s Successors 323-281 BC Volume I: Commanders & Campaigns (Bob Bennett and Mike Roberts, Pen and Sword Books, 2020, $24.95, softcover). Alexander the Great’s untimely death led to decades of struggle to determine who would rule after him. This first volume introduces the key personalities of the story.

Gurkha Odyssey: Campaigning for the Crown (Peter Duffell, Pen and Sword Books, 2020, $49.95, hardcover). The author served as an officer in the Gurkha regiment. His book is a thorough history of the Gurkhas in service to Great Britain.

Gurkha Odyssey: Campaigning for the Crown (Peter Duffell, Pen and Sword Books, 2020, $49.95, hardcover). The author served as an officer in the Gurkha regiment. His book is a thorough history of the Gurkhas in service to Great Britain.

Whispers in the Tall Grass (Nick Brokhausen, Casemate Books, 2020, $32.95, hardcover). This is the second of the author’s memoirs, covering his second tour in Southeast Asia as a member of the Studies and Observations Group. It is well-written and descriptive.

How Armies Grow: The Expansion of Military Forces in the Age of Total War 1789-1945 (Edited by Matthias Strohn, Casemate Books, 2020, $65.00, hardcover). This anthology gathers essays on how military forces expanded during the era of mass armies. It provides insights into how the methods of doing so might be applied to the modern era.

Conquered: Why the Army of Tennessee Failed (Larry J. Daniel, University of North Carolina Press, 2020, $35.00, hardcover). The author analyzes why this western theater Confederate army failed to achieve success. He looks at senior leadership, unit cohesion, and internal administration.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments