By Alan Davidge

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, a 20-year-old German soldier hurried to his post at Wiederstandsnest 62 (WN62) overlooking Omaha Beach to man his MG 42 machine gun. Tossed around in the English Channel in front of him were over 34,000 American troops waiting for their chance to land on that beach and earn their place in history. Thanks to Cornelius Ryan, this date will always be remembered as “the longest day,” but for many of these young troops, it was to become the shortest day of their lives.

For Heinrich “Hein” Severloh, son of a farmer from Baden-Württemburg who had never fired a shot in anger, it was the day he became “The Beast of Omaha.” This is an account of how he conducted himself for nine hours on that day and how he lived with the consequences of his actions for the next 60 years.

“Hein, it’s starting!” The voice of his lieutenant, Bernhard Frerking, woke Private Severloh from his slumbers in a small French farmhouse a few kilometers inland from the coast. Everyone from the 352nd Infantry Division had been expecting something to happen for weeks and knew how to respond. Field Marshal Rommel had always said that when the inevitable invasion occurred, the enemy had to be repulsed within 24 hours or the war would be lost. At this moment, however, Rommel was on the other side of Normandy celebrating his wife’s birthday, and the Führer was enjoying a night’s sleep that nobody dared to disturb.

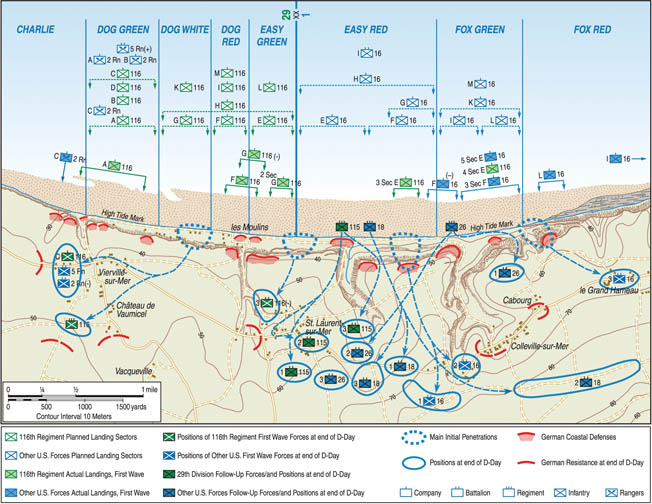

WN 62 was the strongest of the 15 strongpoints overlooking what was to become known as Omaha Beach. They stretched from WN 60 above the Cabourg Draw (codenamed Exit F-1) near the cliffs at the eastern end to WN 74, four and a half miles to the west, just beyond the small coastal village of Vierville.

WN 62 was approximately 325 meters square and was located on the northern slope of the bluffs, giving it an excellent field of fire down onto the beach. It contained emplacements for two 75mm cannons, two 50mm antitank guns, two 50mm mortars, and several machine guns, including an MG 34 on an antiaircraft mount and two prewar water-cooled Polish pieces.

Not all of these guns were operational on June 6. The site, like many others, was a work in progress, as Hitler was continually trying to improve his Atlantic Wall. The whole area was encircled by barbed wire and protected by minefields. In addition, there was a water-filled antitank ditch to impede any invader’s progress off the beach.

WN 62 was also located beside the Colleville-sur-Mer Draw (codenamed Exit E-3), which the Allies had selected as one of the main exits from the beach. It was inevitable that many assault platoons would have been given orders to land in that spot to facilitate their penetration inland.

Severloh’s MG 42, capable of firing 1,200 rounds per minute, was located seven meters from the entrance to the observation post manned by Lieutenant Bernhard Frerking. In addition to repelling invaders, Hein’s job was to protect his officer and enable him to carry out his crucial role of coordinating fire on the targets he identified with a telescope through the slit in his bunker.

Frerking’s vital information was sent to the communications bunker equipped with a transceiver several meters up the slope. It was then passed on to the battery located farther inland at Houtteville, less than three kilometers south of Colleville-sur-Mer and close to the farm where they were billeted, so that it could launch a storm of 105mm shells onto the beach as soon as the invaders appeared. The coordinates had already been provisionally agreed, and there had been a few practice shoots with dummy shells to avoid damaging the beach obstacles carefully placed along the shoreline to rip the hulls out of any landing craft that made it to the beach. Rommel had done his best to have all angles covered.

It was down to Frerking, Severloh, and the 12 other men of the 352nd Division to keep the Allies off their section of the coast. For support, they had 27 soldiers from the 726th Grenadier Regiment and one of the best-located strongpoints on the French side of the English Channel. Strength in numbers they didn’t have, but their armory was formidable and Heinrich would not let his lieutenant down. He had no idea how the day would evolve, but Hein was determined to do his duty.

Hein appears as a quiet, practical young man who could be relied upon to get a job done, capable of using his initiative, and respected by his officers. A farmer’s son who was conscripted in 1942, he became a frostbite casualty on the Russian Front before seeing any action. An unfortunate comment about the failings of his company’s cook resulted in a charge of insubordination, and the resulting punishment inflicted upon him made him a casualty once again. He was transferred to a hospital in Warsaw with severe tonsillitis, and when he fully recovered, he was sent for further training and did not rejoin his old unit, renamed the 352nd Division, until December 1943.

Hein was assigned to the 1st Artillery Battery as an orderly to Lieutenant Bernhard Frerking, a 32-year-old former schoolteacher with whom he immediately established a good rapport. Frerking was an officer he felt he could trust, and his loyalty was reciprocated. They were billeted together in a French manor house owned by the Legrand family in Houtteville, and he began to pick up the language, thanks mainly to Frerking, who spoke fluent French. Despite being the embodiment of Nazi Germany, they did nothing to alienate the locals, and Hein kept in touch with the Legrand family after the war.

The two soldiers arrived at WN 62 at 12:55 amon June 6, and Frerking went straight to his observation post. A sergeant appeared with a box of ammunition and Severloh loaded his MG 42. Soldiers of the 726th Grenadier Regiment were also in position, and everyone waited for first light. The poor weather impeded visibility, but as it became light, it was clear that the horizon was full of ships of all sizes. Not long after 6 am, bombers from the U.S. Eighth Air Force appeared overhead, causing Hein and his comrades to dive for cover.

They were lucky. The poor visibility caused the planes to err on the side of caution as they dropped their bombs so that they landed harmlessly inland of the gun positions. Then the Allied warships opened up with rockets and large shells. The size of the armada and the volume of the ordnance being aimed in his direction told Hein that he was going to have to fight for his life that day, which meant eliminating as many of the enemy as possible.

The first landing craft came into range at around 6:30 am. They dropped their ramps and discharged groups of GIs from the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, “The Big Red One”—not Tommies as expected—who set off for dry land, believing that the Air Force had knocked out most of the opposition.

The D-Day beaches had been minutely classified in the invasion plans to facilitate landing and progression inland, and the sector just in front and to the left of WN 62 was codenamed Easy Red. Just outside Severloh’s main line of fire to the right was the Fox Green sector.

Hein followed his instructions, which were to wait until the troops were knee deep in the water and then open fire. This created immediate panic and forced the survivors and wounded to seek shelter behind the beach obstacles that were designed to obstruct and damage the landing craft. Some found themselves sheltering behind the bodies of dead comrades as they drifted ashore.

Farther below, closer to the shoreline, there were operational problems with an MG 34, so it was Hein’s gun that did most of the damage. (Sometime after the war, Hein met another gunner from the 726th Regiment, Franz Glöckl, who was operating a prewar water-cooled Polish machine gun. Franz was only 18, even younger than Hein, but a hand injury put him out of action after a few hours.)

The first American troops who arrived at low tide were at a range of about 450 meters, and subsequent waves came progressively closer as the tide rose, making them easier to hit. Each dropped ramp revealed 30 potential targets at a time, and an accurate short burst of about three seconds was enough to decimate a platoon.

Given the rate at which the gun discharged its rounds, if one bullet found a target, it was likely to be followed by a couple more. (After the war, Hein met up with an American soldier who had been hit three times as he disembarked onto the beach, making him almost certainly one of Hein’s victims.)

The lull between waves enabled the MG 42’s barrel to cool a little, but nevertheless it had to be swapped regularly. When it was not operational, Hein simply used his Mauser K98 rifle, which he estimated that he fired 400 times that day. He was never short of a target, since the strong west-to-east current drove many of the small landing craft farther along the coast away from their planned landing sites. This meant that even more of them beached within range of Hein’s gun.

Lieutenant Frerking and the remainder of the team were almost totally occupied with identifying targets, setting coordinates, and communicating messages through the zigzag trenches so that the battery in Houtteville could do its work.

Severloh was understandably absorbed in his own task, but he became aware during the course of the morning that his was the only machine gun firing on that part of the beach. (Many years later, he was able to check the German military archives and discovered that a message at 10:12 that morning stated that there was only one machine gun operating at WN 62, which, of course, was his. This also made him think about his personal responsibility for the number of casualties on Easy Red.)

In Severloh’s account of the day, he recalled several waves consisting of 10 to 15 landing craft heading toward his stretch of beach and estimated that six of these appeared before noon. Along the full length of Omaha Beach, each wave totalled about 50 craft, a mixture of wooden-sided LCVPs with an armored ramp and LCAs, which had more substantial protection. When it was clear that the fall of each ramp would be followed by the arrival of about 50 machine-gun rounds, many troops made a premature exit over the sides of the boats, often into water too deep for their heavily laden bodies.

Machine guns are used most effectively when fired into groups, especially in confined spaces. Once the occupants of the landing craft had been targeted this way, the remainder were picked off by rifle fire. One incident that was to haunt Hein Severloh for many years afterward took place when he had switched to his rifle.

Opposite WN 62’s position on the beach today, there stand two concrete blocks. These were originally part of a mill for crushing the beach pebbles into material to construct the bunkers. One American survivor with a flamethrower on his back tried to seek shelter behind this feature, but Severloh brought him down with a shot through his helmet. The individual drama of this event somehow made a more lasting impression on him than the sight of soldiers collapsing in numbers from his machine-gun bursts, and he relived it many times in his dreams after the war.

After about 2 pm, Hein noticed a number of Sherman tanks farther to the west, toward Exit E-1 at St. Laurent, which were moving toward his section of beach. The major components of WN 65 that were guarding the St. Laurent exit had been successfully put out of action by late morning, and columns of American soldiers were ascending various parts of the bluffs.

Hein had used up his allocation of 12,000 machine-gun rounds and had no alternative but to use less-lethal tracer bullets. This carried the risk of highlighting his position, especially to the American warships that were sailing closer to the shore, taking advantage of the rising tide.

It was not long before a shell exploded in front of his position, and he sustained a painful facial wound. By 3 pm, Lieutenant Frerking decided there was no alternative but to abandon WN 62. Many of the 726th Regiment had already been wounded or retreated up the slopes, and his observation post had just sustained shell damage. It was time for the remaining soldiers in his team to exit via the communication trench, which afforded some immediate protection.

Frerking ordered Hein out first and said he would follow. Severloh remembered this as a particularly poignant moment, as his officer used the familiar Du form in addressing him, something that would have been outside the disciplinary code. He took off down the trench as quickly as he could, carrying a hot machine gun and a belt of ammunition.

The first edition of Hein Severloh’s book, WN 62,did not appear till 2000, with the first English edition being published in 2011. Up to that point, the main insight into the day’s events had come from a number of American eyewitness accounts, which are still very accessible and well known. Sifting through these, it is possible to get a good impression of what it was like to be at the receiving end of an MG 42, and also to chart the gradual incursions off the beach that resulted in the strongpoint becoming virtually surrounded.

At H-Hour, 6:30 am, LCVPs containing troops from E and F Company, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division arrived on the beach opposite the Colleville exit. Company E commander Captain Ed Wozenski reported that as soon as the men left their craft to wade ashore, they came under intense machine-gun fire, falling into the bloody water until only a few of them reached the shingle bank.

They were followed by several LCVPs containing men from the 116th Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, who should have landed much farther to the west but had been pushed farther eastward by the currents and foul weather. For these men, their landing strategy was shelved in favor of survival.

Within an hour, the headquarters company of the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry landed to the left of Easy Red, just below Severloh, under intense automatic weapons fire and found

survivors of the first waves pinned down on the beach. A reserve regiment from the 18th Regiment, 1st Division was due to land before noon, and they sent in an early reconnaissance team that had to revise their schedule when they realized the intensity of the fire from WN 62.

Unknown to Hein at the time, he was also firing at a celebrity target. Robert Capa, one of the best known photojournalists of the war, had hitched a ride on an LCVP, and his heroics with a camera to bring home some of the most graphic images of the day were nearly brought to an end by Private Severloh. Around 11 am, Ernest Hemingway, never destined for a quiet retirement, approached Easy Red, but the pilot of his boat veered off to a different section of the beach when he realized how dangerous it was to land there.

In addition to the infantry, the early waves contained men from the 5th Special Engineer Brigade, who reported very heavy fire between Colleville and the next beach exit to the west at St. Laurent-sur-Mer, codenamed E-1. Severloh later confirmed this by mentioning that in a lull between waves, he saw a red flag that one survivor had placed in the sand below him to guide subsequent landing craft.

Around the same time, a few duplex-drive Sherman tanks had arrived on the beach, and one succeeded in knocking out two 75mm guns on the other side of the Colleville exit, enabling troops to make progress up the bluffs. Below Severloh, however, there was no movement off the beach, and the situation had become so critical by 8 amthat the cancellation of the assault on Omaha had become a real possibility.

Observers peering through binoculars from vessels offshore, though, could see that small groups of men had begun climbing the bluffs farther east in the areas of WN 61 and WN 60. Despite the hang-ups at Omaha, they could see that the invasion plan was working. Hein wouldn’t know until years later that his dogged determination to prevent passage off the beach could have changed the course of events that day.

Of course, the mortar and artillery fire directed from WN 62 played a major role in the carnage on this section of the sand, but Hein also facilitated this indirectly by providing the covering fire that allowed his lieutenant and the rest of his team to do their jobs effectively and send back the coordinates for these targets.

What Hein and his comrades didn’t know was that as early as 1:15 pm, Captain Joe Dawson and a group from G Company, 16th Infantry were already on the outskirts of the little town of Colleville, directly inland of him at the head of the draw. During the course of the morning, Dawson had found a route up the bluffs to the west. This, together with the earlier incursions up the other side of the Colleville Draw, meant that Frerking’s decision to fall back at 3 pmwas not a moment too soon. Effectively, they were surrounded.

Hein’s escape route out of WN 62 took the line of least resistance: trenches, craters, anything that helped him keep his head down. After a while, he dropped into the sunken lane leading to the village of St. Laurent-sur-Mer and waited for the rest of his team. Only one appeared: Kurt Wernecke the radio operator, who relayed the shocking news that all the others, including Frerking, had been killed. Within a couple of minutes, they were themselves caught by a burst of machine-gun fire, delivering painful flesh wounds, but they managed to stumble on to WN 63, where a medic administered first aid.

They recuperated for a while, but by midnight the whole group, including a wagon full of wounded and some American prisoners (one of whom coincidentally had German parents and spoke a familiar dialect) decided to move inland under cover of darkness. Shortly before dawn, they came under fire again, and it was clear that they were surrounded. Reluctantly and ironically, they asked their own prisoners to accept their surrender.

The GIs who took them prisoner were from the 16th Infantry, the main regiment at which Severloh’s machine gun had been firing all morning, so he had to be very careful not to give away too much information about himself.

One of the men captured at the same time had been based at WN 61 on the other side of the Colleville Draw, and he provided Hein with a graphic but discreet description of the damage his gun had inflicted on American troops. In an area below his position, and invisible to him at the time, were hundreds of bodies piled up where the sea had left them.

Although wounded, Hein spent the next couple of days helping others less fortunate than himself in a temporary POW camp at Vierville at the opposite end of Omaha Beach. He was then shipped to England and from there to the United States to work in a variety of camps along the East Coast from Boston down to Florida, mostly to help with harvesting crops, including potatoes and cotton.

In his book, he recalls another incident that stirred his conscience about events on D-Day when he and a friend discovered an old copy ofStarmagazine that contained a graphic description of a place he knew well: “Men carrying weapons could not get to the beach on Easy Red because the bloody mess floating around was so high that the soldiers couldn’t wade through it and kept sliding.”

Severloh remained a POW after the war, and in March 1946, he was sent to Belgium and then to England and Scotland. Finally, after his aging father pleaded for help on the farm, Hein was released in April 1947.

Hein did his best to settle back into farm life when he returned home, but there was no way he could bottle up his wartime experiences forever. Many of them demanded some kind of closure, however difficult that was going to be.

First of all, he had to contact Lieutenant Frerking’s family. His parents managed to set up a visit from Frerking’s mother two weeks after his arrival. Her son was still listed as missing, but Hein was able to confirm his fate as reported to him by Karl Wernecke.

He then sent a sketch of WN 62 to the Legrand family with whom he had been billeted and asked if there was any trace of a grave on the site. Fernand Legrand was soon able to visit the site, where he discovered a wooden marker. After consulting the authorities, he traced Frerking to a cemetery constructed above the beach. (A number of temporary cemeteries were created in the area that frequently contained both American and German dead. Eventually, the majority of German remains were transferred to a cemetery at La Cambe, just a few miles due south of Omaha Beach in the late 1950s. This is Frerking’s final resting place.)

The most positive event for Hein Severloh upon returning home was a meeting with Lisa, a girl he first met just before being posted to France. They were able to pick up where they had left off in 1943 and were eventually married in 1949. For a while, she became the only person to whom he could talk about the war, as he became very depressed, remorseful, and introspective.

The memory of the single flamethrower-carrying soldier he had shot with his rifle at the gravel mill on the beach strangely affected him more than the carnage he created with his MG 42, and he suffered frequent sleep deprivation. He became very anti-establishment and even joined the Association of Conscientious Objectors in Hannover.

Like many returning soldiers, Hein tried to forget about the past, but he found it impossible to ignore the popular magazine articles entitled “Sie Kommen” (“They’re Coming”) by Paul Carell that appeared in 1959. Perplexed as to why none referred to his area of Omaha Beach, he contacted the author, who saw him as a valuable witness to the liberation, and helped him to contact other comrades as the magazine developed into a book (Invasion—They’re Coming!).

In 1961, Hein made his first visit back to Normandy for the opening of the German military cemetery at La Cambe, accompanied by Frerking’s mother and widow. He also visited the site of WN 62, which was completely overgrown. (Today, the main features have been exposed again so that it is possible to trace the bunkers and trenches.)

He also met the Legrand family for the first time since D-Day and discovered that Frerking had telephoned them at 7 amfrom his bunker, warning them of the invasion and advising them to drive to Bayeux for safety, 10 kilometers away. His view was that both the Germans and the Allies would respect the city as an historical monument, making it less likely to be shelled or bombed.

This gesture demonstrates the relationship they had with the people whose house and village they had occupied. Although the Legrands were a respected family locally, they were taking a risk by being friendly with the Germans since they knew (rightly, as it turned out) how the French would deal with collaborators.

Mister Legrand then made Hein an astonishing offer by asking him, as an experienced farmer, to take over his own farm in Houtteville, as his only son had tragically died young, and he and his wife were of advanced years. After much consideration, Hein felt that he had to decline the offer because of the logistics involved, but he kept in touch with the Legrands for the rest of their lives.

Hein Severloh continued to make new contacts as a result of his relationship with Paul Carell. The most significant of these came when Paul gave Hein the first edition of The Longest Dayby Cornelius Ryan, which was to become the classic D-Day account.

In it, Hein read the story of David Silva, who had come under heavy fire in front of Easy Red Beach at Colleville in the early afternoon. He was hit three times by a machine gun firing tracers, which meant there could have been only one person responsible: Private Heinrich Severloh!

Hein was now on a mission. He discovered that David Silva had become a priest and moved to Akron, Ohio, but his letters were returned due to frequent changes of address. He eventually tracked him down in Karlsruhe, Germany, and it was not long before the two veterans were engaged in an emotional and cathartic reunion that was to spawn a friendship and respect for each other that lasted forever.

As the years passed, many more contacts were made with D-Day veterans. In 1984, Hein received a call from Franz Glöckl, the 18-year-old soldier of the 726th Grenadier Regiment who had been firing from a position just below him.

Glöckl had arranged a reunion with men from WNs 60, 61, 62, and 63 and invited him along. This helped to fill in many of the gaps in his knowledge of what took place on June 6, 1944, helped Hein come to terms with the trauma he had faced.

On one visit, he met Jack Borman, whose duplex-drive Sherman he remembered as being caught in the shingle below him on the beach. It was his tank that had taken out one of the 75mm artillery pieces on WN 62, and Jack’s expression of remorse for the casualties he had caused was a further reminder to Hein that war affects soldiers on both sides in similar ways.

From as early as 1960, when Paul Carell’s book, Invasion—They’re Coming!, was first published, Hein received attention from a number of quarters, especially authors and journalists. But the most bizarre encounter occurred in 1984 when an English reenactment group invited him to the United Kingdom. It called itself the Association for the Rehabilitation of the Honor of the German Wehrmacht Soldiers. Its members wore uniforms very precisely decorated with medals and insignia and observed very accurately the military procedures with which Hein was all too familiar.

They also went as far as presenting him with a medal similar to a Purple Heart to which he was entitled by virtue of the wounds he sustained on D-Day. He politely accepted and took his leave, totally bewildered and wondering why anyone would want to play-act events that had brought so much misery to him and so many others.

There were other authors who, in his opinion, sought to sensationalize him and failed to stress the antiwar message that he was trying to get across. He also received offers to appear in a number of documentaries and requests for interviews with French and German magazines. Despite his best attempts to maintain control, he found journalists all too ready to put words into his mouth and ask leading questions.

At the end of one interview following the 40-year anniversary in 1984 with the American ABC network, he was persistently asked on camera how many men he had brought down, and as he declined to reply, a figure of 1,000 was suggested to him. Possibly to end the interview, he conceded it was likely and that it may have been twice that figure. This admission helped to unburden him a little, but it also gave him the notoriety that brought even more attention from journalists, authors, and filmmakers.

In 1999, he was contacted by a leading D-Day author, Helmut Konrad Baron von Keusgen, who soon realized the crucial role that Hein had played on that day, and he offered to help him write his own personal account. Thus began a friendship that allowed Hein to unburden himself 55 years after D-Day of the traumas he endured, and this friendship finally gave birth to the book WN 62, which told the full story.

Not surprisingly, this created further interest from journalists and filmmakers, but it was an invitation to appear in a film in 2003 that brought everything to a head for him. Hein was taken to the beach below WN 62 and asked to start walking toward another man farther along the shoreline. As they got closer, he realized it was David Silva, the man who had taken three bullets from his gun on D-Day and who Hein had tracked down after discovering his account in The Longest Day.It was 39 years since their first reunion.

Hein and David spent four emotionally charged days together filming, reliving the events that brought them together and catching up on all that had happened since. A visit to the American cemetery near WN 62 made particular demands on their emotional reserves, and both decided that this would be their last trip to Normandy, which indirectly guaranteed that they would never meet again in this life. Hein’s health finally failed him in 2006. David lived till 2010.

Hein Severloh’s assessment of the carnage he caused on D-Day was based on his own observation of that section of the beach below his firing position and on what he learned from other soldiers he met some time afterward who saw bodies piled up within his field of fire, some of which may have drifted along the coast. This was reinforced by stories in the media that could have exaggerated his contribution to the casualty list, and it is only fairly recently that any detailed work has been done on the figures.

In his very comprehensive account Omaha Beach(2004), Joe Balkoski estimates the total U.S. casualties (killed, wounded, missing) on D-Day at around 4,700. To try and understand Hein Severloh’s role in this final roll call, it is important to look at the total defenses.

The beach was protected by 15 Wiederstandsnest bunkers, as well as large-caliber guns located farther inland. Severloh himself states that there were 85 machine guns in position along the beach, although not all of them were operational that day.

In addition to German weaponry, there were natural factors that caused loss of life. The waters of the English Channel claimed many crew members of the duplex-drive Sherman tanks that launched unsuccessfully offshore, and then there were the infantrymen who jumped off of landing craft into deep water before the ramps went down to avoid exposure to heavy fire, causing them to drown.

Omaha Beach is more than six kilometers long. The 29th Infantry Division landed in the western half, although the weather and currents certainly carried some of their 116th Infantry boats down to Easy Red. The 29th suffered about 1,350 casualties. The 1st Division, which landed in the eastern half stretching from a point west of WN 65 to below WN 60, suffered only 70 fewer casualties. The remaining units who landed along the full length of the beach, chiefly engineers, completed the casualty list.

After just a brief study of the casualty figures, it becomes clear that only a limited proportion of them could have arrived in a location that brought them within Severloh’s sights. Those that did could also have become victims of shells, mortar bombs, and a variety of other machine-gun and rifle fire that was also aimed in their direction. To try and investigate any further, I believe, would be an essentially academic exercise and would do nothing more for the memory of those men whose lives were brutally cut short on D-Day or to enhance the study of history.

It nonetheless seems reasonable to state that, without the intervention of Private Heinrich Severloh, the U.S. Army would have been around a battalion stronger when it left the Normandy beachhead.

The publicity that Severloh attracted in later life, which bestowed upon him the title “The Beast of Omaha,” was largely of his own making. He could have returned home and continued where he left off in his local farming community and kept his thoughts to himself. But his curiosity and his conscience got the better of him and took him down a path that brought him face to face, again and again, with the most shocking and terrible day of his life.

From his writings and the many interviews that we can now easily retrieve from the Internet, there is no evidence of him trying to glorify what took place. He does not appear to try and cast himself as yet another victim of the war or to ask for sympathy. In exposing his guilt, he took many risks and, in his regular visits to Normandy, could have encountered others who still sought revenge.

Hein’s contribution to World War II is something that he would have preferred to forget. But he couldn’t. Instead, he chose to reveal it to the world so that we are all aware of the consequences of one country declaring war on another, thereby challenging us to look for better solutions to conflict unless we can justify it all happening again.