By Phil Zimmer

Stephan H. Lewy was young, militarily inexperienced, and A Most unlikely American soldier. Yet when he reached Utah Beach 30 days after D-Day, he was all business as a staff sergeant in U.S. military intelligence, attached to the 6th Armored Division that shortly became part of General George S. Patton’s hard-charging Third Army.

To all appearances, Staff Sergeant Lewy was yet another fresh-faced 19-year-old called upon to rise to the occasion for his country, but his personal history was far more complex. Lewy, a Jew, had been born in Berlin and managed to escape several times from the proverbial mouth of the lion as the Nazis swept across much of Europe. Against nearly overwhelming odds, he successfully made his way to America in June 1942.

Lewy became one of the nearly 2,000 German-born Jews who were secretly trained in military intelligence work at Camp Ritchie in western Maryland. The “Ritchie Boys” knew the German language and its rich idioms as well as the culture, making them uniquely suited to plumb the minds of Nazi prisoners. And they were exceptionally motivated, because many had lost family and friends to the dark forces that had engulfed Europe.

Lewy’s father had suffered physically ever since he was picked up by the Nazis in 1932 and sent to Oranienburg. He was arrested because he was Jewish and was active in socialist circles, two marks against him as far as the Nazis were concerned. He was beaten badly and lost a number of teeth. He was held for about a year, and the Nazis released him after he suffered a heart attack.

Just weeks after Kristallnacht, his father began the paperwork at the American consulate for admission to the United States, where relatives had promised to support the three of them until they were on their feet.

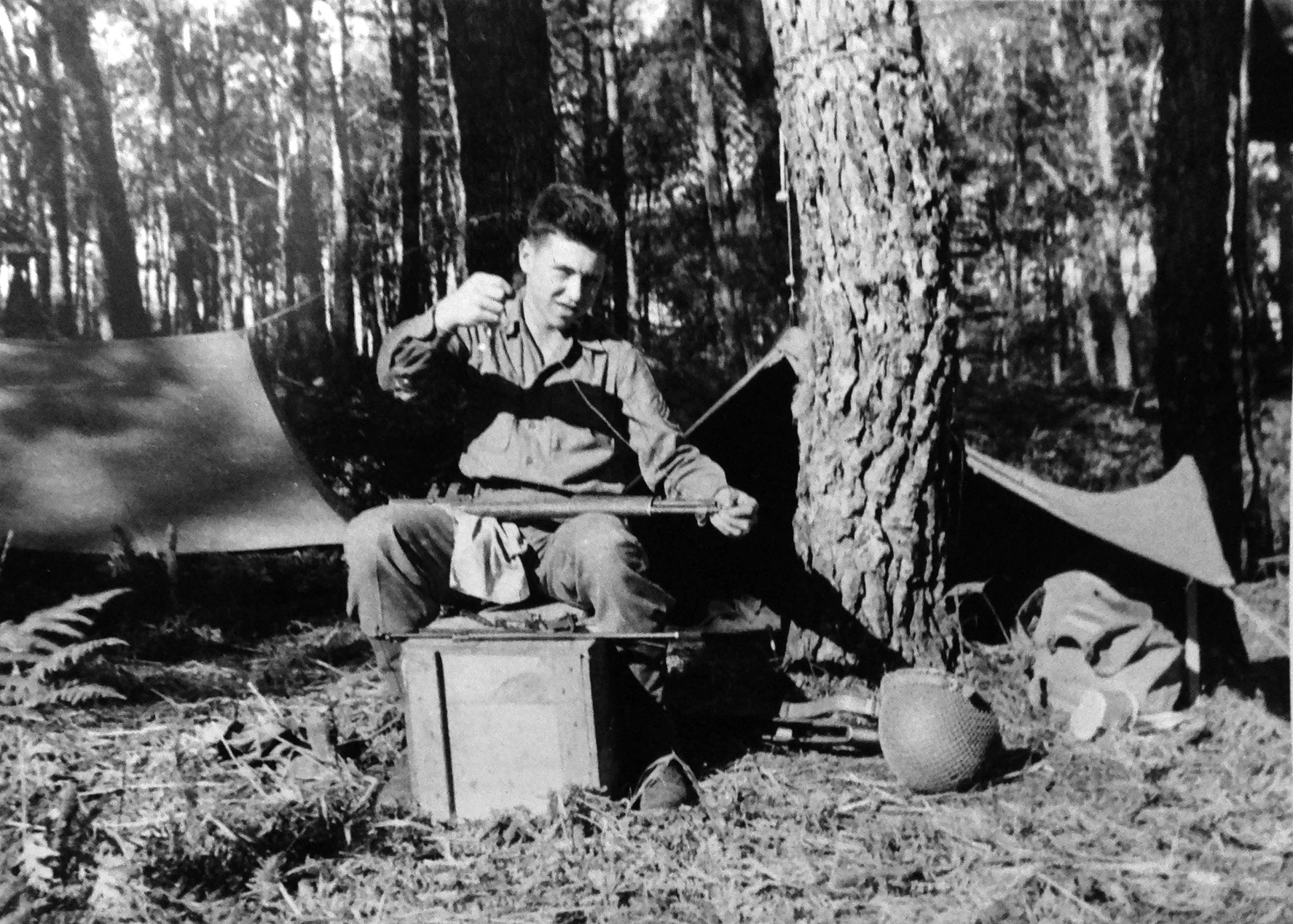

The eight-week Camp Ritchie training program prepared Staff Sergeant Lewy and others in “non-forceful” interrogation techniques that would be used to question the very men who had persecuted them and their families. They served on the front lines to obtain crucial, firsthand information from German prisoners, aware all the while aware that their own capture would almost certainly mean death.

Lewy knew that recently captured soldiers were often disoriented, scared and hungry. He and his compatriots had detailed information on the captured Germans’ units—officers’ names, the units’ battle histories, equipment and the like.

“We used that information to overwhelm prisoners with our expansive existing knowledge. This would often get them talking in the belief that we already knew everything anyway,” says Lewy.

And they also worked to establish rapport with the captured Germans, finding common interests to lower their guard. They were taught not to rough prisoners up, but some did resort to putting a pistol in clear view to build some anxiety and help “clarify” a captive’s mind.

The Ritchie Boys learned map-reading, how to identify a prisoner’s unit and rank from his uniform, and the ability to read and analyze captured documents. Every German soldier carried a pay book, which listed where and when he was assigned to each unit and when he was promoted. The pay books proved invaluable.

“Among other things, we could compare the pay books to our existing unit records and update them if necessary. We also were taught to quickly recognize the rather distinctive sounds of different German, Italian and even Russian rifles and machine guns,” notes Lewy.

Lewy never physically abused a prisoner, but he did once did ask a recalcitrant SS prisoner to put his name on a piece of wood and nail it in the form of a cross “…so he could later be identified. When that failed to work, I had him taken outside, handed him a shovel and asked him to dig. After a few minutes, I asked him to lie down beside the hole to make sure it fit. He broke at that point and suddenly became very forthcoming,” Lewy recounts.

Other men developed their own methods to get prisoners talking. Ritchie Boy Fred Howard headed an effort to obtain bombing information on German industrial targets, such as tank factories, for Allied air campaigns. Prisoners from such areas would obviously be reluctant to provide such information, knowing that it would likely result in the aerial pulverization of their hometowns.

When a prisoner refused to discuss these prime military factories, Howard would apologize. He would then say he had orders that recalcitrant prisoners were to be turned over to Commissar Krukov.

The prisoner would then be taken to Guy Stern, another American interrogator, who was decked out as“Commissar Krukov, Liaison Officer,” complete with uniform and medals of the USSR.

Howard and Stern knew the Germans feared being taken prisoner by the Russians. A special interrogation tent had been set up, complete with a photo of Stalin.

After the prisoner’s encounter with “Commissar Krukov,” Howard would walk the prisoner back to his office, where the German would invariably disclosed the information being sought to his American interlocutor.

Another Ritchie Boy, Martin Selling, was interrogating one particularly arrogant and uncooperative prisoner when the German asked where Selling had learned to speak such perfect German. It was at a small town, Selling reported, called Dachau, where he personally saw how the SS interrogated prisoners. Presumably, the prisoner became far more cooperative after learning that his interrogator had once been a witness to a Nazi concentration camp.

“We were taught not to strike the prisoners; not to even touch them. It made sense anyway, because information obtained through physical means would have been nearly worthless, with a prisoner saying anything to stop torture, as many Nazi interrogators discovered,” adds Lewy. “We were not going to be like them. We were Americans and were determined to work at a higher standard.”

Lewy served with a fighting unit, an advancing unit, so “I looked primarily for tactical information that could be put to use right away in our drive into Germany. Troop size, location, equipment and enemy morale were all immediately important.”

But the Ritchie Boys were also instructed to keep an eye on the bigger picture. One, for example, came across a fellow who had served at Peenemunde, the secret Nazi missile test site on the Baltic Sea. He immediately called in U.S. Army Air Forces intelligence officers to more precisely debrief the man on what he did there and what he knew, according to one report.

Lewy’s unit was also involved in the Battle of the Bulge, where “snow, fog, trees and cold were hallmarks of my experience as we forged ahead under Patton’s Third Army to help the encircled American troops. Heavy snows, difficult terrain and enemy resistance created frustrating delays.”

During the Battle of the Bulge, some English-speaking Germans managed to infiltrate the lines dressed as American soldiers in an effort to sow confusion. “That certainly worked, and it also caused me substantial personal concern as well, because of my rather conspicuous German accent. You can bet that I stuck close to my officer, Lieutenant Szabo, throughout the battle, because he could vouch for me. I was like a bug on flypaper with him for more than two weeks,” Lewy adds.

Getting captured would not have been pleasant for Lewy, and while in Europe he was always near the front lines. He had his dog tags changed from H for Hebrew religious affiliation to O for none, but his last name still would have been a giveaway to a suspicious German interrogator. In fact, two of the Ritchie Boys were captured, identified as “German Jews,” and executed by the Nazis during the Battle of the Bulge, according to reports.

One of Lewy’s more interesting experiences involved getting an false American officer arrested as a spy. “We were in Breidfelt having breakfast in a small cafe,” he commented. “I noticed an American officer at the next table who never changed his knife from his right hand to his left like Americans do when eating.”

Lewy rose and approached a 6-foot, three-inch MP and stated that the man was not an American officer. He looked puzzled as he listened to Lewy speaking with a German accent the distinctive European method of not moving utensils between hands while eating. Intrigued, the MP approached the individual and spoke with him for a few minutes before hustling him out of the restaurant. The impersonator managed to glower at Lewy on the way out, confirming his suspicions.

At one point, Lewy’s unit discovered a German bunker just beyond the Siegfried Line. It was deserted, but the telephone system there had been left intact, along with a map on the wall that listed all the telephone numbers in the nearby bunkers which, naturally, Lewy could read.

With a go-ahead from American headquarters, Lewy called the Germans and asked for their surrender. A Nazi officer in one bunker vehemently stated they would not surrender, and then Lewy heard a shot. The German enlisted men then started coming out, hands raised. Once inside that bunker, the Americans discovered the German officer’s body lying where he had been shot in the chest, killed by his own men who had opted to live.

Despite Lewy’s best efforts, the Germans in one bunker refused to surrender. Two bulky Americans, each carrying flamethrowers, were sent over. They went to work, and the Germans were soon running from the bunker with their uniforms and hair aflame. A couple of other Americans vomited, but the two soldiers working the flamethrowers moved on to their next assignment, apparently accustomed to seeing the results of their work.

Later, in lower Bavaria, Lewy’s unit found extensive police records in the city hall. Reading through the detailed records, he found the names and locations of all the Nazi party leaders living in the city. Lewy was given the go-ahead to round them up and arrest them. Over four or five weeks in the city, he located and turned over more than 170 prisoners to higher authorities. It was one of his most gratifying experiences of the war.

“I took solace, though, in knowing that the prisoners would not receive the same type of treatment that the Nazis had meted out to their prisoners, including my father a decade earlier in Berlin,” he adds.

Lewy’s unit liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp in April 1945. “We were sickened and shocked by the stench and conditions in the camp,” he recalled. “The prisoners were like walking skeletons, with the dead lying about in contorted positions. Many of the battle-hardened Americans were overcome and cried like babies.”

As Lewy walked through the camp, he quietly murmured Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. “Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world which He has created according to His will, Amen.”

“I felt true anger and rage, especially when I came across piles of human bones lying outside the ovens,” he said. “The prisoners who were alive were barely alive, with skin hanging from their emaciated bodies. One officer entered the SS office and saw pieces of tattooed skin apparently taken from prisoners, a lamp shade made from human skin, and even a couple of shrunken heads.”

Lewy was ordered to round up local Germans and force them to view the horrors of the camp. The locals were also pressed into service to dig a grave and help clean up human remains lying about the camp. In addition, he drove into nearby Stuttgart every morning to fill two trucks with elderly Germans who were also pressed into service. The old men dragged the corpses and dropped them on top of each other in a large grave.

“I and the other Americans had a hard time even then containing ourselves,” said Lewy. One soldier shouted obscenities at an elderly German man. “How could they not have known?” asked another American, speaking almost to himself.

Lewy’s unit served under Patton, and he was present at some of divisional briefings given to the general. “His boots were always polished, and his pistols at the ready, but he would invariably ask which plan of attack being proposed would present the fewest causalities,” Lewy remembered. “His concern for his men was a side of Patton that was not widely publicized. We also learned that unpacking was often a waste of time because Patton always wanted his men to be on the move.”

“You got to get in your mileage for the day,” Patton reportedly said to his commanders in half jest.

“He was always on the move. Patton believed that it was better to be on the attack to keep the Germans on the backs of their heels,” Lewy adds.

By July 1945, the war in Europe was well over, and Lewy had earned the Bronze Star and five campaign medals. Those, coupled with his service time abroad, meant that he was among the first to head home with the knowledge that he would soon be sent to the Pacific. Shortly after he arrived stateside, he learned that the atomic bombs had been dropped on Japan and that World War II had ended. He was delighted to be reunited with his mother and friends, but his father had suffered another heart attack and had passed away.

In recent years, Lewy has spoken to more than 1,000 school children. “My message has been called simple yet profound,” he concluded. “Enjoy the life you have. Make the best of it, even if it seems out of control. Move forward; things will improve. I stress the responsibility of everyone to be respectful and to love their neighbor.”

Staff Sergeant Lewy used the GI bill to attend night school at Northeastern University. He graduated in accounting and earned his CPA designation. He married a young American girl, and the couple had two children. Before retirement he worked for two Boston-based hotel chains. The 94-year-old is a widower, who now resides in the Buffalo, New York, area.

Author Phil ZimAuthor Phil Zimmer is a U.S. Army veteran and a former newspaper reporter. He has written on a number of World War II topics.

Thanks for sharing this extremely interesting account of SSG Lewy’s service.