By Mike Phifer

It was almost dark when Captain Chase Philbrick led a reconnaissance party of 20 volunteers from Company H of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry across to Harrison’s Island situated in the middle of the Potomac River. It was October 20, 1861, and the men had orders to slip across to the Virginia side of the river at Ball’s Bluff to see if the Confederates had reacted to a demonstration made earlier in the day.

The men climbed into two skiffs and rowed as quietly as possible across the still river to the foot of Ball’s Bluff. Once ashore the scouts followed a cart path up the steep 100-foot bluff. It was dark as the scouts reached the top and moved south in the hazy moonlit night.

After traveling about three-quarters of a mile, Philbrick suddenly spotted something up ahead. There appeared to be about 30 tents among a row of trees along a ridge. Philbrick and his men crept to within 150 feet of the camp. Strangely, they could not spot any sentries or campfires. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to attack the seemingly unwary Confederates, and Philbrick quickly headed back to the two skiffs.

Rowing back to Harrison’s Island, Philbrick reported his findings to Colonel Charles Devens. In less than 12 hours a substantial body of Federal troops would return to Ball’s Bluff only to find that things were not as they appeared in the moonlight.

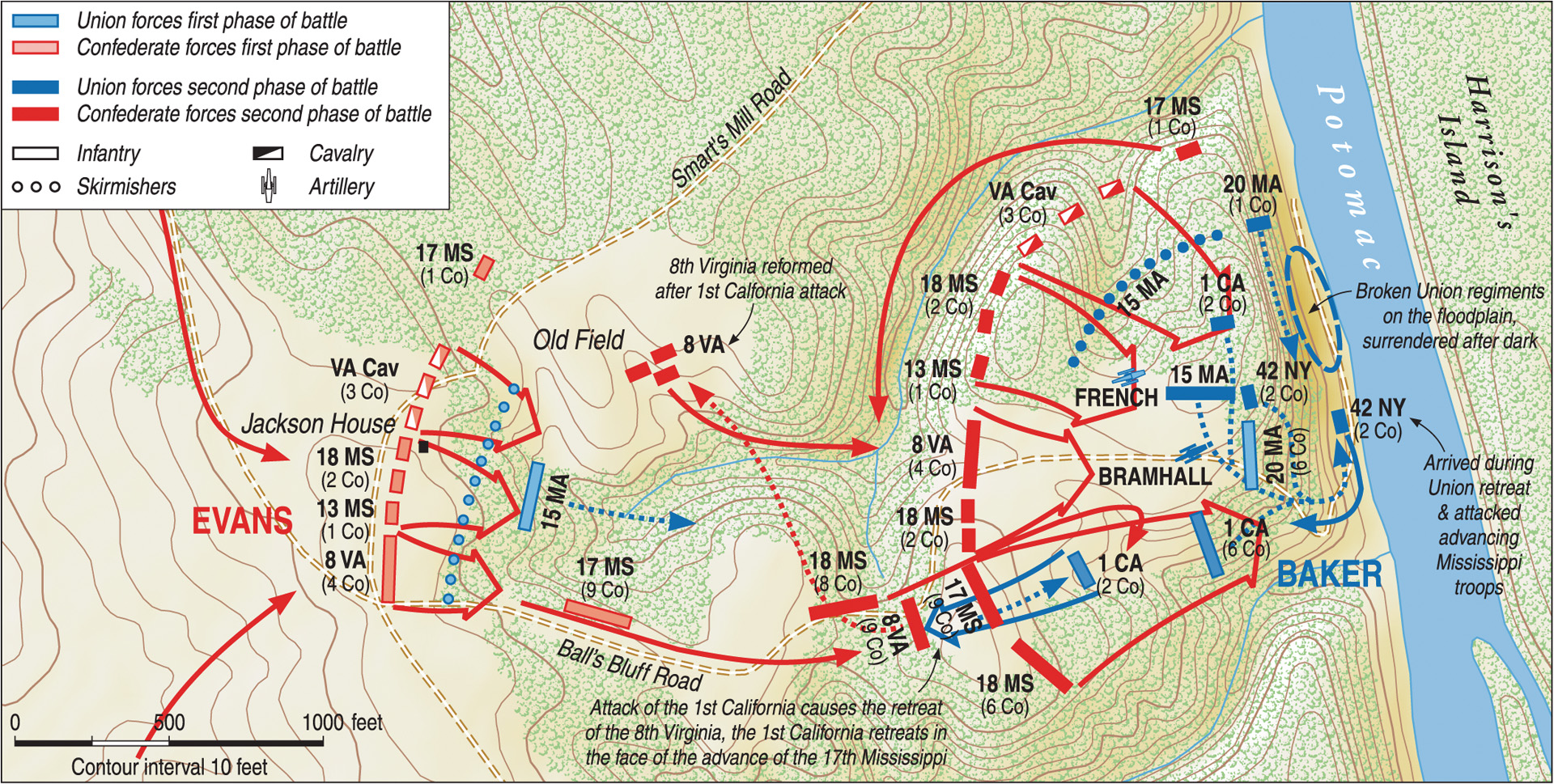

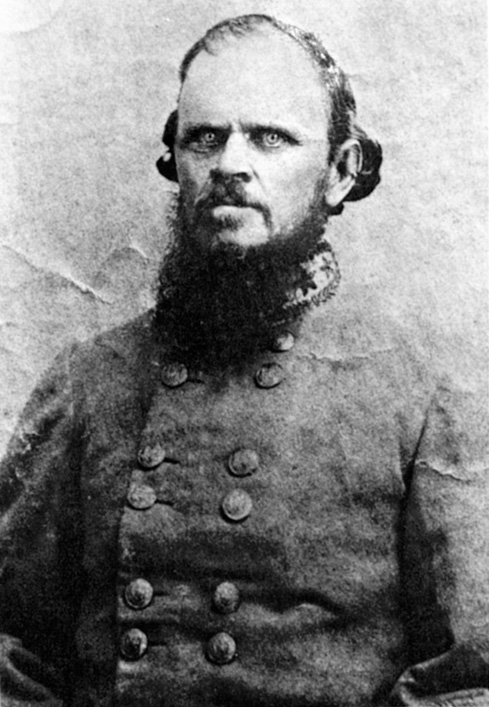

After its victory at Bull Run on July 21, General Joseph Johnston’s Confederate Army of the Potomac, which was based at Centreville, Virginia, had established a line of outposts along the Potomac River. The westernmost of these outposts was at Leesburg, which was located about two miles southwest of Ball’s Bluff. The Confederate officer responsible for covering the gently rolling farmland of Loudoun County around Leesburg was South Carolina native Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans. Evans had posted his mixed brigade, which comprised three Mississippi regiments and one Virginia regiment, close enough to the steep cliffs overlooking the river to prevent the Federals from establishing a foothold on Loudoun soil.

Evans’ superiors had praised him for the leadership and bravery he exhibited at Bull Run. As commander of the Confederate outpost at Leesburg, he was responsible for covering the approaches to Leesburg, namely for guarding Conrad’s Ferry and Edwards Ferry, as well as various nearby fords. Evans established an earthwork called Fort Evans about two miles northeast of town and set up his headquarters there. To hold the area, Evans had placed his brigade, which consisted of the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi and 8th Virginia Regiments, near the river. His command also included five companies of Virginia cavalry under Lt. Col. Walter Jenifer and Captain John Shields’ 1st Company, Richmond Howitzers. Altogether, Evans’ force totalled 2,800 men.

On the north side of the Potomac River, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ division covered the section from Washington, D.C., to Edwards Ferry, Brig. Gen. Charles Stone’s division covered the section from Edwards Ferry to Point of Rocks, and Colonel John Geary’s 28th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers covered the section from Point of Rocks to Harpers Ferry. It was important for both sides to cover the Potomac from Washington to Harpers Ferry because if one army were to cross in strength it might possibly outflank the other army.

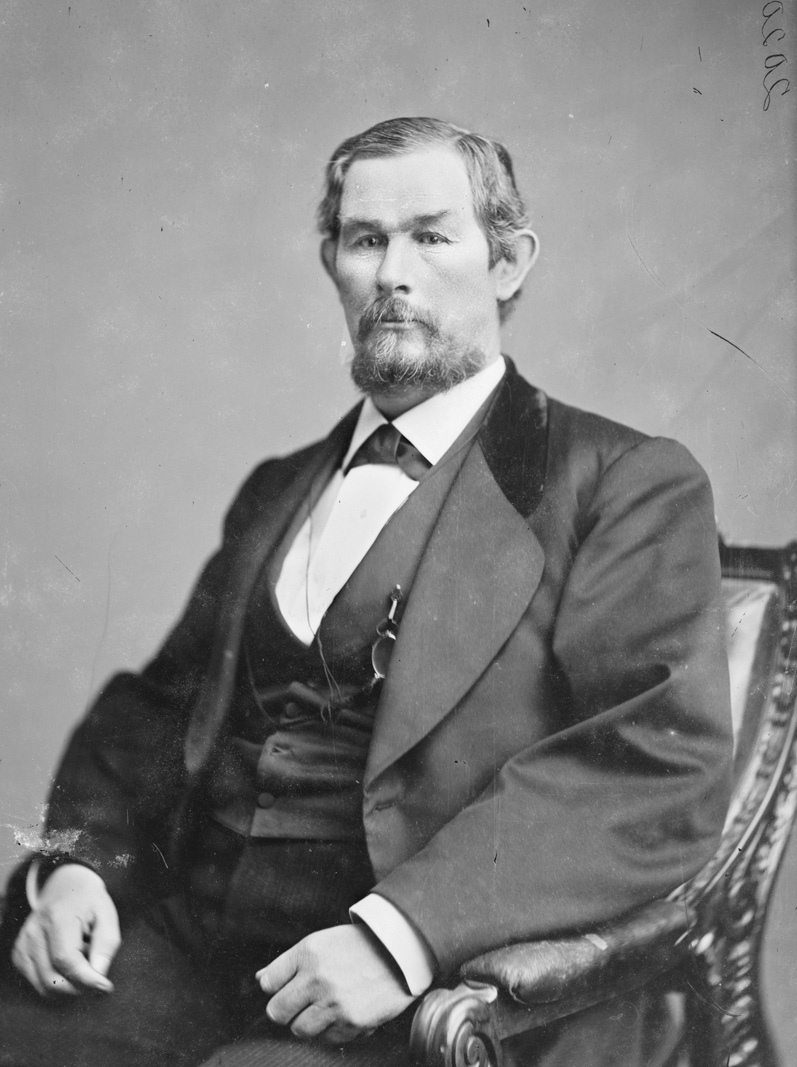

A graduate of West Point in 1845, Stone left the U.S. Army 11 years later to take up civilian pursuits in California. He returned to the military when he was commissioned a colonel on January 2, 1861, and later was promoted to brigadier general. By October, Stone’s 12,000-man division consisted of three brigades, two unassigned regiments (42nd New York and 15th Massachusetts), four companies of the 3rd New York Cavalry, a detachment of Maryland cavalry, two other cavalry companies (later to be part of the 2nd New York Cavalry), and three artillery batteries. Brig. Gen. Frederick Lander commanded the First Brigade, Brig. Gen. Willis Gorman led the Second Brigade, and Colonel Edward Baker led the Third Brigade (curiously known as the California Brigade even though its regiments were from Pennsylvania).

Major General George McClellan, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, received reports during the third week in October that Johnston might be withdrawing Evans’ brigade to Centreville. What prompted these reports was Evans’ decision to fall back from the river the night of October 16-17 for fear that the Federals were trying to surround him. When his superiors found out that he had pulled back south of Leesburg, they ordered him to return to his original position covering the river crossings in his sector.

Not wasting any time, McClellan ordered Brig. Gen. George McCall to march his division 15 miles west from Langley to Dranesville and then to send out probes to determine whether Evans had withdrawn. In addition, the move would allow McCall to make maps of the area that would benefit future operations. When McClellan learned that Evans was still at Leesburg, he ordered McCall on the evening of October 19 to fall back to Langley.

The next day, October 20, McClellan’s adjutant sent a message to Stone at his headquarters in Poolesville, Maryland, which read: “General McClellan desires me to inform you that General McCall occupied Dranesville yesterday, and is still there. Will send out heavy reconnaissances today in all directions from that point. The general desires that you keep a good lookout upon Leesburg, to see if this movement has the effect to drive them away. Perhaps a slight demonstration on your part would have the effect to move them.”

Following orders, Stone sent troops to Edwards Ferry to deceive the Rebels into believing they were being attacked from two directions. What Stone did not know was that McClellan ordered McCall to return to Langley after he finished his mapmaking and that on October 21 McCall’s division would no longer be at Dranesville.

Evans learned of McCall’s march on Dranesville from a captured Union courier and took up a defensive position behind Goose Creek. Positioned on the west side of the creek four miles southeast of Leesburg, Evans waited for an attack from the east that never materialized.

In the interim, Stone began to make his demonstration at Edwards Ferry. On the afternoon of October 20, he ordered part of Gorman’s brigade—the 1st Minnesota and the 2nd New York State Militia—along with the 7th Michigan from Lander’s brigade and two companies of the 3rd New York Cavalry, to Edwards Ferry. Stone moved his headquarters to Edwards Ferry to direct the demonstration. When the Federal infantry arrived, they found a battery of the 1st U.S. Artillery lobbing shells across the river to scare off any Rebel pickets. Stone had his troops launch boats at the ferry to deceive the Rebels into believing he was crossing at that point.

Stone ordered other troops to various locations upstream from Edwards Ferry. They were not supposed to attack; instead, they were meant to provoke the Confederates into either defending the crossings or abandoning them. Stone also ordered four companies of Colonel Charles Devens’ 15th Massachusetts to Harrison’s Island, which was located three miles upriver from Edwards Ferry and opposite Ball’s Bluff, where they would join another company from the regiment already stationed there. The 20th Massachusetts from Lander’s brigade also was ordered to the vicinity of Harrison’s Island. In addition, the 42nd New York and a battery of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery were sent to Conrad’s Ferry, which was two miles upriver from Harrison’s Island.

At Edwards Ferry Stone ordered Gorman to send a small detachment of troops across the river as part of the demonstration. Gorman ordered Colonel Napoleon J.T. Dana, commander of the 1st Minnesota, to send two of his companies across the river. Near sundown, the men of Companies E and K climbed into three flatboats and pushed off into the current. After landing on the Virginia side of the Potomac, the Federals drove off some Rebel pickets. After about 15 minutes the Yankees returned to the north bank. Stone then notified McClellan that he had “made a feint of crossing” at Edwards Ferry, adding that he had “started a reconnoitering party toward Leesburg from Harrison’s Island.” This party was led by Philbrick.

After receiving Philbrick’s report, Devens quickly sent word to Stone about the Rebel camp. In August, McClellan had advised Stone, “Should you see the opportunity of capturing or dispersing any small parties by crossing the river, you are at liberty to do so, though great discretion is recommended in making such a movement.” Stone intended to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the enemy’s carelessness in not posting pickets at its camp.

Stone ordered Devens to take five companies and cross the river at Ball’s Bluff. Devens was to rout the Rebels and destroy their camp. After doing this, Devens was to return to his present position unless he found a good position to establish a bridgehead. Stone specified that the bridgehead would have to be one that Devens could hold until reinforced and could be defended against superior numbers. If he took that course of action, he was to report back that he had done so.

Neither Devens nor a number of his soldiers were excited about the mission. One officer in the 20th Massachusetts quipped that Devens “seemed like a man who had made up his mind that he was going on a forlorn hope.” The five companies Devens was taking with him numbered about 300 men, and he had a covering force of two companies numbering about 100 men from the 20th Massachusetts under the command of Colonel William R. Lee. It took Devens about five hours to get his men across to the Virginia side of the Potomac. This was because they had only two skiffs and a copper lifeboat that could carry about 30 to 35 men per trip.

At daybreak on October 21, Devens and his five companies set out for the Rebel camp, while Lee remained at the top of Ball’s Bluff with his covering force. Devens and Philbrick soon found the tree line in the growing light, but no Confederate tents or a camp. Further investigation revealed a nearby farmhouse and four tents near Leesburg, but there was no camp nearby. In the dim light of the previous evening Philbrick had mistaken a row of trees for enemy tents.

In the meantime, Stone decided to aid Devens’ force by drawing the Rebels’ attention away from him and conducting a reconnaissance in the direction of Leesburg with his force at Edwards Ferry. The Union commander ordered Gorman to send two companies of the 1st Minnesota and a detachment of about 30 cavalry across the Potomac River at Edwards Ferry. While the infantry guarded the bridgehead, the cavalry under Major John Mix were to ride along the Leesburg Turnpike until they came near the Confederate fortification on that road. At that point, they were to turn left and “examine the heights between that and Goose Creek” to see if there were any Rebels in the area and determine their numbers and position.

Under the cover of artillery fire, the two companies of infantry and cavalry crossed the river a little after dawn. While the infantry spread out in a skirmish line about 400 yards away from the river, Mix led his cavalry detachment on its scouting mission. Near Fort Evans, situated on a knoll on the Edwards Ferry Road, the Federals bumped into Evans’ Mississippi troops and exchanged gunfire. After a brief skirmish, Mix withdrew to Edwards Ferry, where the troopers were posted as vedettes.

Believing he was undetected by the Confederates, Devens decided not to withdraw to Harrison’s Island. Instead, he sent a report back via Lieutenant Church Howe and stayed in his position near the phantom camp and Margaret Jackson’s farmhouse. He intended to exercise the option Stone had given him to hold on until reinforced.

While Devens was investigating the phantom encampment, Lee at Ball’s Bluff had sent out patrols to protect his flanks. One of the small patrols traded shots with nearby Confederate pickets, who quickly withdrew and reported to their Company K commander, Captain William Lewis Duff of the 17th Mississippi, who sent word on to Evans of the Yankee presence.

Posted about a mile northeast of Leesburg at Big Spring, Duff with 40 men headed out to link up with the rest of the Confederate forces. The Rebels followed a hollow to a hill near the Jackson House where Devens’ pickets spotted Duff’s little command at 8 am. Devens ordered Philbrick to take Company H and attack the Rebels, while Captain George Rockwood’s Company A moved to the right to cut the enemy’s retreat toward Conrad’s Ferry.

Duff realized the Yankees outnumbered him, and he fell back about 300 yards down the slope toward Leesburg with Philbrick’s company in pursuit. Duff formed his troops to face the 65 Yankees who were pursuing them. As the Federals moved toward his company, Duff yelled “Halt!” He did this a few more times, with the Federals replying, “Friends!” When the Federals got to within 60 yards of him Duff ordered his men to kneel and fire.

A sharp skirmish ensued. Devens, who was with Philbrick, sent an order for Company G to give assistance. But before the reinforcements arrived, the Yankees learned that Confederate cavalry was approaching from Leesburg. Devens ordered Philbrick to withdraw, which Duff did as well. With one man killed, two missing, and nine wounded, Philbrick’s company took up position on the edge of some woods behind a rail fence south of the Jackson House.

Suffering three wounded, Duff and his company fell back about 300 yards. He was reinforced by four companies of cavalry under the command of Jenifer, who hearing of the Union advance around 8 am had ridden toward the sound of gunfire. Jenifer did not remain long with Duff; he soon received orders recalling him to Fort Evans. When Jenifer arrived at Fort Evans at 9 am, Evans kept one of Jenifer’s cavalry companies but sent him back with about 70 men to reinforce Duff. Evans ultimately would send four companies, which were drawn from the 17th, 18th, and 13th Mississippi.

Meanwhile, Devens led his men back to Ball’s Bluff where Lee went over to meet him. He found Devens “very much vexed [and] angry,” wrote Lee. “If you are going to stay here, colonel, you better form your line of battle across the road, instead of leaving your battalion in column and halted in the road,” Lee said. Devens did not respond. Instead, he left his men where they were for 30 minutes and then marched them back to their position in the woods near the Jackson House.

At Edwards Ferry, Howe delivered Devens’ message to Stone around 8 am informing him there was no Rebel camp. The Union commander quickly sent Howe to tell Lt. Col. George Ward, second in command of the 15th Massachusetts, to take the rest of the regiment and proceed to Smart’s Mill, located at a narrow part of the river about a half mile north of Ball’s Bluff, allowing him to protect Devens’ right flank.

Howe was sent back to Devens and delivered his orders to Ward along the way. At about the same time, Stone ordered his temporary aide, Captain Charles Candy, to take 10 cavalrymen and a noncommissioned officer and cross the Potomac. Once across, they were to unite with Devens and act as scouts for him.

Candy would not make it to Devens, though; at Ball’s Bluff Lee ordered him to report back to Stone. He was to tell Stone that they had gained a foothold on the south bank of the Potomac River and that if the government meant to launch a campaign then both reinforcements and additional boats would be needed.

Meanwhile, Howe delivered Ward his orders to cross over to Harrison’s Island and then move on to Smart’s Mill. The young officer crossed the Potomac and moved inland to join up with Devens near the Jackson House. Once he arrived at the front, Devens debriefed him on his fight with the Rebels and ordered him to report this to Stone. On his way back to Edwards Ferry, Howe met Ward on Harrison’s Island, slowly moving his five companies of infantry to the island due to the small number of boats. Howe informed Ward that Devens was being pressed hard and could use his support. Believing that Devens was asking him for help, Ward decided to go to his aid instead of Smart’s Mill.

Up to that point, Baker’s brigade had done little in the day’s growing events. The 1st California under Lt. Col. Isaac Wistar had moved from Conrad’s Ferry, where they had arrived at first light, to the crossing point from the Maryland shore to Harrison’s Island. After visiting briefly with Wistar, Baker rode along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath to Edwards Ferry. There he met with Stone sometime around 9 am to get his orders for the day. Stone informed him of the situation and ordered him to Harrison’s Island, where he was to take command of the Union force’s right wing. The Union commander warned Baker not to engage the Rebels if they outnumbered him and not to advance south of Leesburg.

Baker wanted in writing the order that he was to assume command. Stone jotted down the orders, which read: “Colonel: In case of heavy firing in front of Harrison’s Island, you will advance the California regiment of your brigade or retire the regiments of colonels Lee and Devens upon the Virginia side of the river, at your discretion, assuming command on arrival.” Baker then rode back to Harrison’s Island intending to cross the river and engage the Rebels.

By about 10 am, Evans had determined that the Yankee crossing at Edwards Ferry was a feint, believing the main attack would be at Ball’s Bluff. He dispatched nine companies of the 8th Virginia Infantry under Colonel Eppa Hunton to reinforce Duff and Jenifer, leaving one company near the burned bridge at Goose Creek. But before they arrived, Jenifer engaged the Yankees.

“At 11 o’clock I determined to attack the enemy, and, if possible, drive him from his strong position,” wrote Jenifer. The Confederate attack drove in the Federal skirmishers, which included some of Ward’s men who were positioned along a treeline near the Jackson House, back to Devens’ main line posted near the edge of the woods. Heavy firing from the main Yankee line caused Jenifer to temporarily retreat.

At 12:20 pm, the 8th Virginia arrived on the field, and Hunton took over command. The Rebels quickly formed into position with most of the Mississippi troops in front with skirmishers deployed. The 8th Virginia supported these companies, while Duff’s company and the dismounted cavalry were on the extreme left about three quarters of a mile to the north. They had orders to advance toward Smart’s Mill. The main line advanced on Devens’ 15th Massachusetts men. Due to the thick woods and rough ground, the Mississippi and Virginia troops lost sight of each other, and after a short time the Virginians were in front with the Mississippians on their left.

“After marching several hundred yards through dense woods our troops were fired upon by the enemy’s skirmishers,” wrote Jenifer. With both sides about equal in number the fighting raged into the early afternoon.

About the time that Hunton arrived with his Virginians to reinforce Jenifer, five companies of the 20th Massachusetts under Major Paul Revere crossed over to the Virginia shore with two mountain howitzers to join Lee and the two companies of the regiment posted on Ball’s Bluff. More troops would arrive as the afternoon dragged on. Unfortunately, transfer of the 1st California and 42nd New York from Maryland to Harrison’s Island to Virginia was painfully slow due a shortage of boats. Meanwhile, Baker spent valuable time overseeing a canal boat transferred to the river to help facilitate the troop crossing.

While Union troops began massing at Ball’s Bluff, Stone received a message from McClellan informing him that he might be required to take Leesburg. Stone replied that he thought the Confederates numbered about 4,000 men and were receiving reinforcements but believed he could do it. “We are a little short of boats,” Stone informed McClellan.

Stone sent word to Baker to push the enemy if he could and if possible to establish a strong position near the town. Baker was ordered to report back on his progress and also determine whether the Rebels were retreating. Stone sent the rest of Gorman’s brigade across the river at Edwards Ferry with orders to strike the Confederate right flank.

About 1:30 pm Baker finally crossed over to Ball’s Bluff and conferred with Lee as to how he had deployed his force. Lee had five companies of the 20th Massachusetts drawn up in a battle line across a 10-acre clearing at the top of the bluff. On both sides of the Federal position were deep ravines. Lee had placed a mountain howitzer on each end of the line and also ordered a company to deploy as skirmishers on each flank. Baker began to deploy troops from the 1st California as they made their way up the bluff. Then Baker turned to Lee and asked his opinion on the troop deployment. Lee told him he thought the battle would be made on the left. Baker also posed the same question to Wistar, who had just arrived on the field. Wistar believed the left flank was weak and exposed to enemy fire from a cluster of wooded hills that overlooked the Union position. “I throw the entire responsibility of the left wing upon you,” said Baker, when Wistar asked for skirmishers to cover that area.

With his flanks being threatened and fearful of being cut off, Devens fell back to Ball’s Bluff at 2 pm. There he finally made contact with Baker, who rearranged his defensive position. The 15th Massachusetts was positioned to the right of the 20th Massachusetts and perpendicular to it along a wooded edge facing south onto the field. To the left of the 15th were two companies of the 1st California, while another two companies of this regiment were placed on the left flank of the 20th Massachusetts.

Colonel Milton Cogswell of the 42nd New York arrived shortly after 2:30 pm on the Virginia shore with Company C of his unit and a James rifle from Battery B of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery. The gun proved too heavy to be pulled up the steep slope by horses and had to be dismantled and manhandled up the muddy trail with ropes. To make matters worse, Duff’s little force, which had reached the river, was firing down at them from a wooded hill north of the landing site. Cogswell sent his company to disperse Duff’s detachment. A half-hour skirmish took place before the Rebels pulled back.

Cogswell made his way to the top of the bluff where Baker asked his opinion of the troops’ position. “I told him frankly that I deemed them very defective, as the wooded hills beyond the ravine commanded the whole so perfectly, that should they be occupied by the enemy he would be destroyed,” wrote Cogswell. The 42nd commander advised that the whole force should be sent quickly to occupy those hills. Baker did not take Cogswell’s advice but did order Wistar to send out two companies to scout the vulnerable Federal left.

At 3 pm, Wistar, acting on Baker’s orders, ordered Captain John Markoe of the 1st California to take his Company A and move forward. Wistar then led Company D and followed about 30 yards behind him. They were to scout the woods in front and locate the Rebels’ right flank. They would not have to go far.

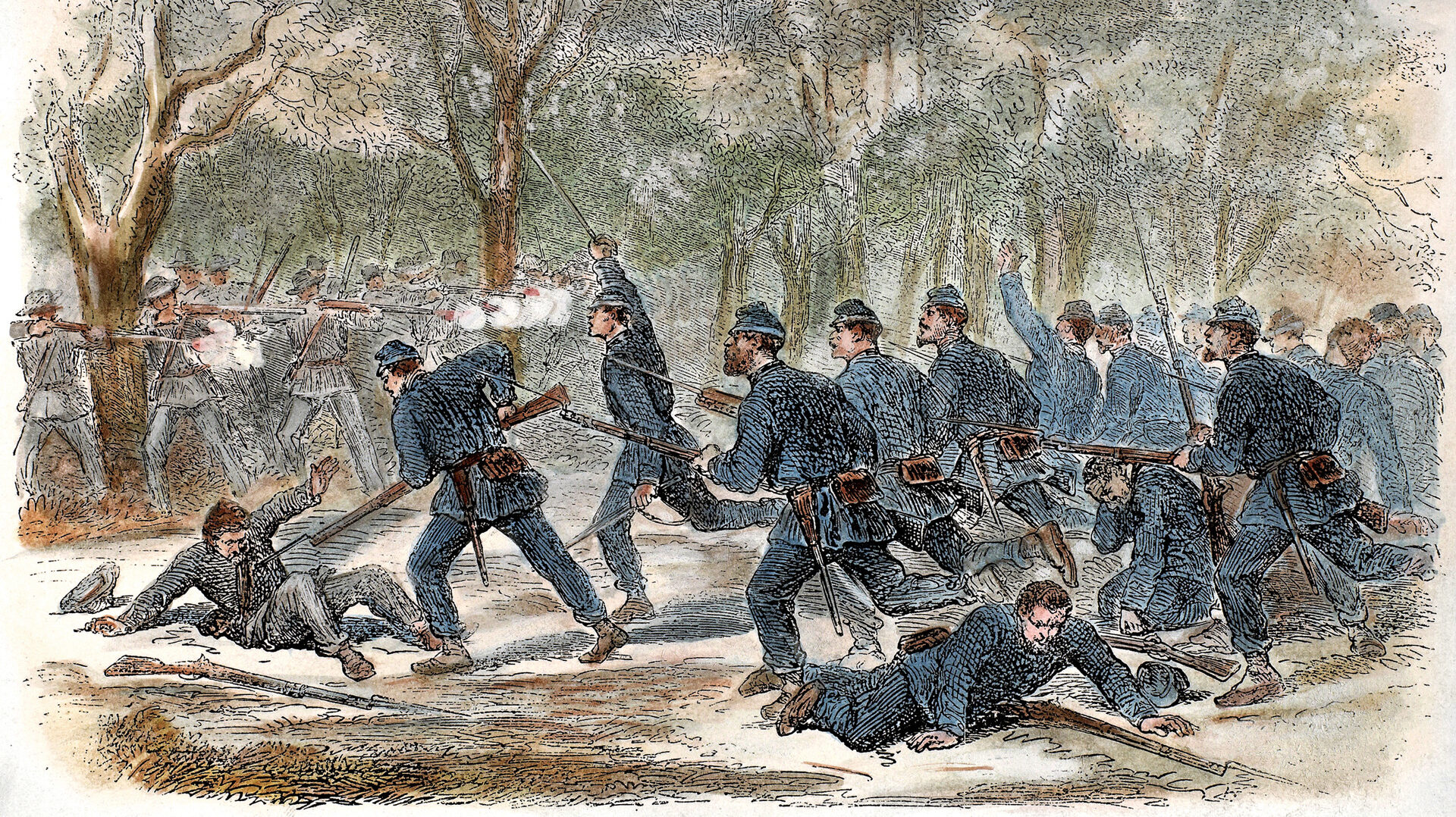

After Devens had retreated back to Ball’s Bluff, Hunton moved his force forward. He placed his right on the high ground that commanded the Yankee left. While Hunton’s left was protected by woods at the western end of the field, the bulk of the Confederate forces were positioned north of the cart path. Earlier Hunton had sent a number of messages to Evans asking for reinforcements, and eight companies of Colonel Erasmus Burt’s 18th Mississippi were dispatched to his aid with nine companies of the 17th Mississippi under Colonel Winfield Scott Featherston being sent shortly afterward. The 18th had not yet arrived at Ball’s Bluff when an element of the 8th Virginia south of the cart path rose up and fired on Markoe’s men, catching them by surprise. A sharp firefight ensued.

More firing broke out north of the cart path as some of the Confederates fired on the main Federal line. Wistar quickly left command to Markoe and ran back to take command of his regiment. Markoe’s command lasted only about 15 minutes. He was wounded and captured while his men fell back fighting after suffering heavy casualties.

The Federals were not the only ones to fall back. Hunton had ordered his men to fall back, but several companies panicked and ran. Lt. Col. Charles Tebbs, Hunton’s second in command, was retreating with these men, but according to Hunton he “and a portion of the men with him returned to the line of battle. Some of them went home, but not many.”

Hunton struggled to consolidate his remaining troops. When the 18th Mississippi arrived on the scene, Hunton’s men shifted to the left allowing the Mississippian to deploy in their former position.

Across the clearing, the James rifle rolled onto the field, with the 20th Massachusetts making room for the gun and horses to get through and take up position in the center of the Union line. Equidistant from the James rifle were the two mountain howitzers, which supported the Union right and left flanks. The Rebels fired on the horse team of the James rifle. The two lead horses were shot, while the rest became frantic. The horses broke their traces and galloped down the hill dragging the limber. The unlimbered James rifle opened up on the enemy, but the Rebels shifted their fire to the crew. Most of the crewmen were killed or wounded, and the gun fell silent.

Burt soon advanced with the bulk of the 18th Mississippi. The Rebels advanced diagonally across the field toward the angle of the Federal line. Apparently Burt could not see the men of the 15th Massachusetts inside the edge of the woods on the northern part of the field. When the Mississippians came to within 100 yards of the Yankee position, the Yankees unleashed a deadly volley, stopping the Confederate attack. Burt, who was mortally wounded in the advance, would die three days later.

Command of the 18th Mississippi now fell to Lt. Col. Thomas Griffin, who ordered the regiment back and divided it into two battalions. He sent the larger detachment to the right in an attempt to flank the Yankee left. This move produced a 200-yard gap in his line, which was soon filled by the newly arrived 17th Mississippi.

About that time, Stone, who was at Edwards Ferry, received a message from McClellan ordering him to take Leesburg. Unfortunately, it was encoded and Stone did not have the means to decode the message. It did not matter much because the day was growing long, and events were about to take a turn for the worse for the Federals at Ball’s Bluff.

Fighting continued to rage at Ball’s Bluff, even though most of the fighting on both sides was uncoordinated with units acting independently. Confederate pressure on the Federal right was not a serious threat; however, the same could not be said on the left flank. The 18th Mississippi’s right battalion managed at about 4:30 pm to get around the Federals left flank. Baker ordered over two companies of the 15th Massachusetts to reinforce his left. The Mississippians launched repeated attacks against the Federal left, which was defended by elements of the 1st California, 15th and 20th Massachusetts, and 42nd New York Regiments.

In one of the advances, Wistar was struck by a minie ball in the hip. It was his second wound of the day. Nevertheless, he stayed in the fight, even helping to man the James rifle. Lieutenant Walter Bramhall, who was in charge of the gun, was aided after his crew had been shot down not only by Wistar but also by Cogswell, Lee, other officers, and even Baker, who helped roll the gun back into position after its recoil. They were soon replaced by volunteer infantrymen.

On the Confederate right, the Mississippians attacked again. Wistar was shifting troops to face the new attack when he received his third wound. Baker helped him to his feet and ordered a soldier to get the wounded officer to a boat. Baker remained in the action, but not for long.

At 5 pm Baker was shot and killed. The troops around him were thrown back, leaving Baker’s body unattended. As the Confederates surged closer to Baker’s body, Captain Louis Bieral of Company G, 1st California, rallied a group of men from his regiment to recover Baker’s body. The men rushed forward. Bieral shot a Confederate who was bending over the body. More troops from both sides rushed in, and a sharp fight raged over the body, which eventually was retrieved, but not before Bieral was wounded several times.

The situation was turning worse for the Federals. Lee met with Devens and ordered a retreat back across the Potomac. Cogswell soon joined the two officers. He claimed seniority to Lee, and he believed they could break out and cut their way to join Gorman at Edwards Ferry. Cogswell ordered Devens to bring his men from the right of the line to the left to support a column of attack by the 1st California and three companies of the 42nd New York, two of which had just recently arrived.

Cogswell’s breakout attempt ended in failure. The Rebels quickly moved into the woods from which the 15th Massachusetts had withdrawn. Then, a Confederate officer, Lieutenant Charles Wildman, suddenly appeared on a gray horse in front of the 42nd New York, took off his hat and waved it, and ordered them to charge. Apparently he mistook the 42nd in their gray uniforms for Confederate troops. They obeyed the order believing he was a Union officer and surged forward. The men of the 15th Massachusetts started to charge, too, but were stopped by Devens. The New Yorkers on the other hand were badly shot up.

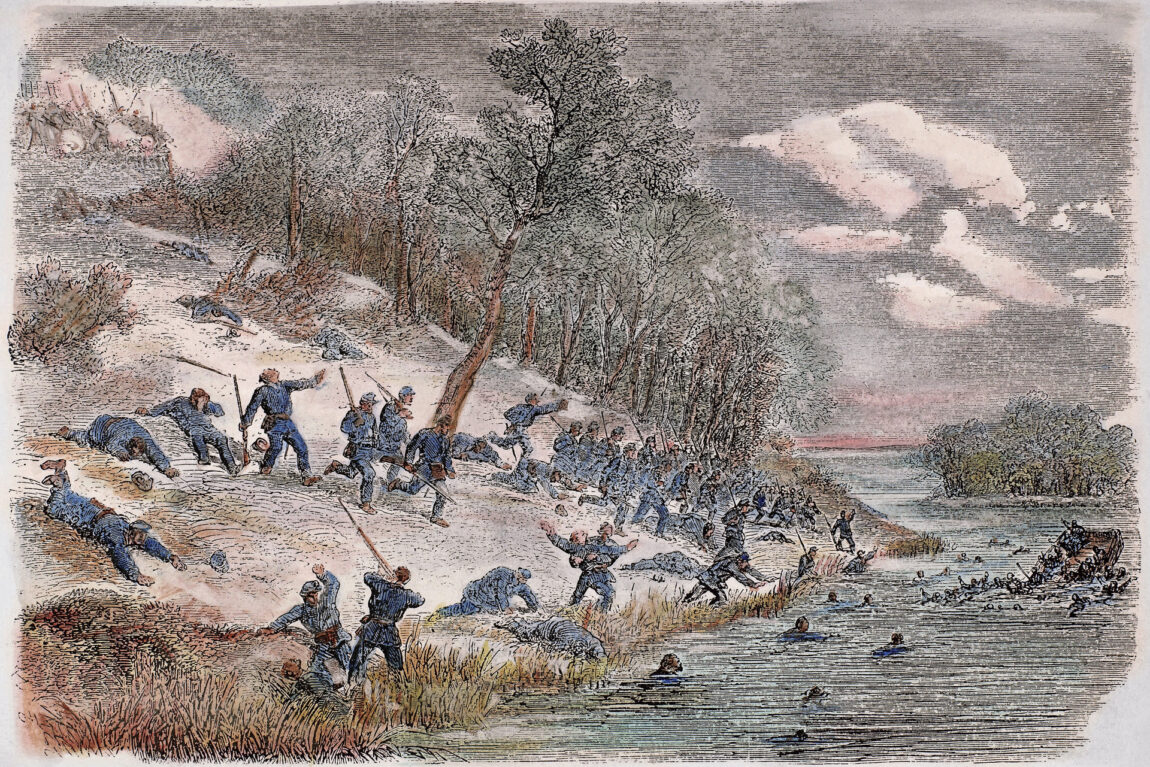

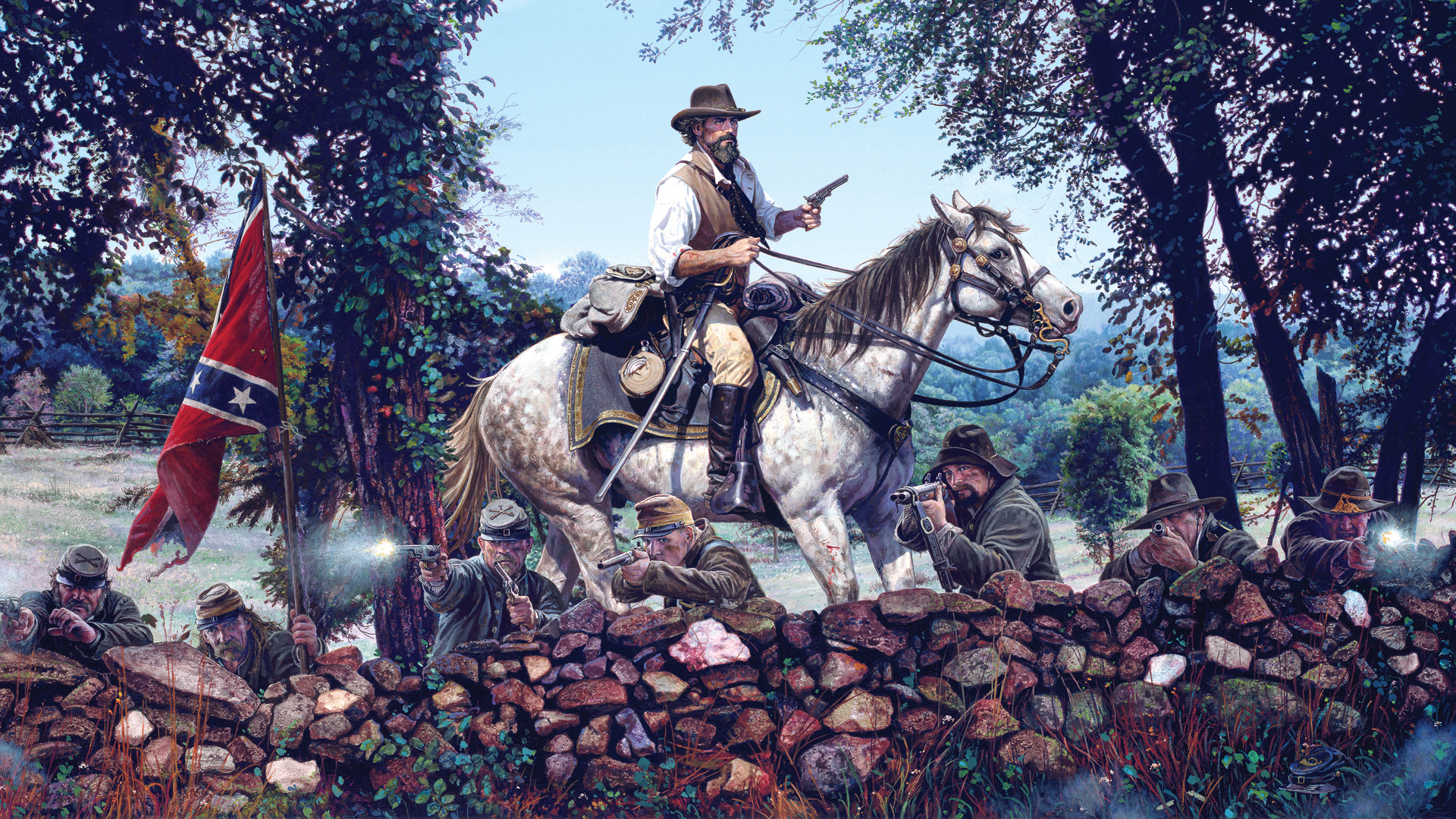

Hunton, with his 8th Virginia now back in action, ordered a charge. Mississippi and Virginia troops drove back the Yankees and captured the two mountain howitzers. The troops of the 8th Virginia were now completely exhausted and withdrew to the rear.

Not long after the Virginians’ withdrawal, Featherston of the 17th Mississippi ordered a charge, “Forward, charge, Drive the Yankees into the Potomac or Hell!” The 17th and 18th Mississippi troops advanced close to the enemy when Featherston ordered them to fire and charge. The Yankees were overwhelmed. Featherston would claim that his men captured the James rifle during the attack, while most Federal accounts state the gun was rolled off the bluff.

By this time, Cogswell had determined that retreat was the only option. He said as much to Devens and ordered him to retreat. Although the 15th Massachusetts made a brief stand at the edge of the river among some trees and two companies from the 42nd freshly arrived put up a brief fight, they, like the rest of the troops, broke. Many of the Federal troops scrambled down the path for the river, while others were driven back to the edge of the bluff. The Yankees huddled on the brow of the cliff “in one wild panic-stricken herd, rolled, leaped, [and] tumbled over the precipice…. Screams of pain and terror filled the air,” said Private Randolph Shotwell of the 8th Virginia. Some of those who jumped landed on the bayonets of the troops below.

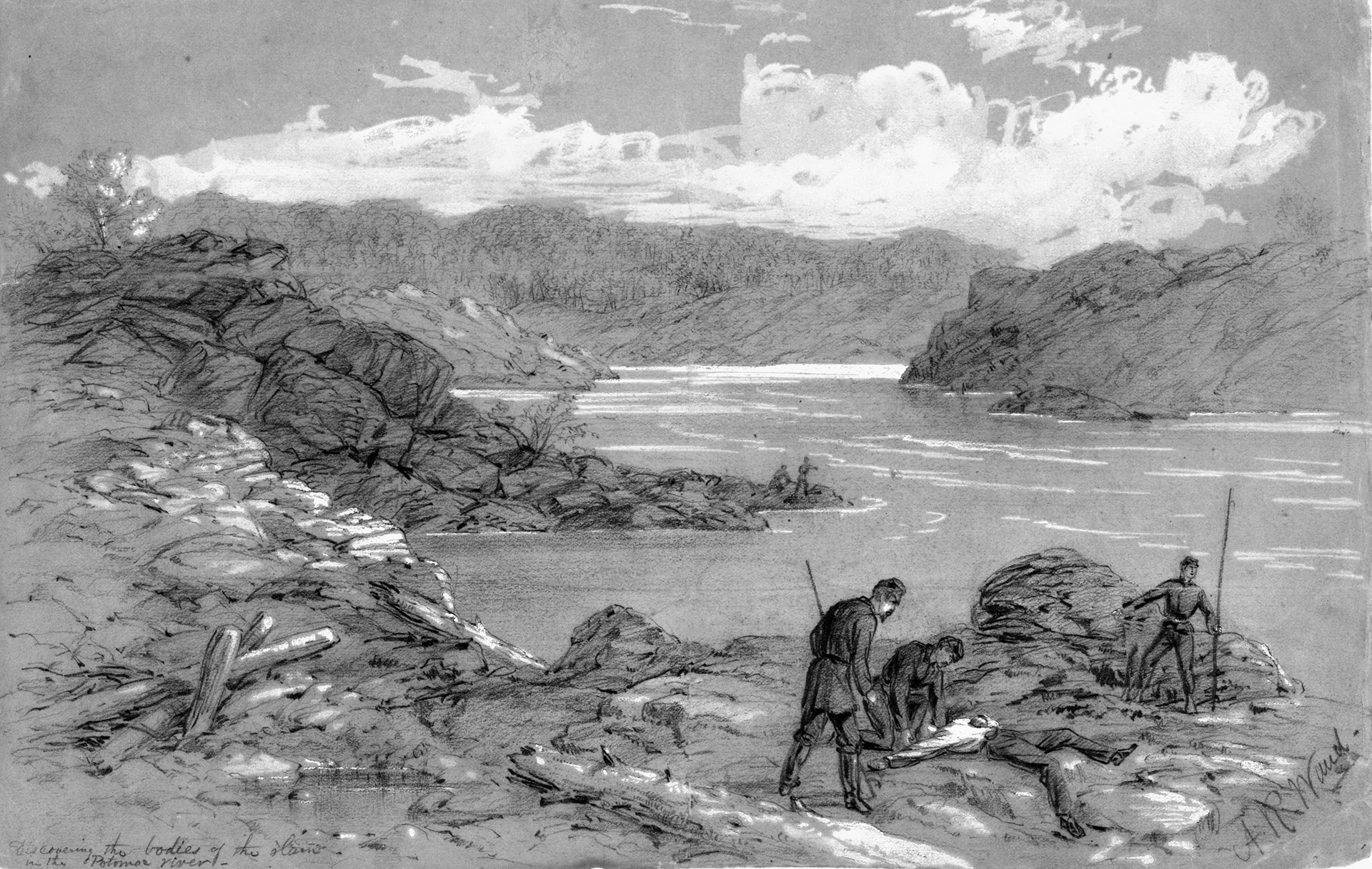

“Here was a horrible scene,” said Captain William Francis Bartlett of the 20th Massachusetts. “Men crowded together, the wounded and the dying. The water was full of human beings struggling with each other and the water.” To make matters worse, Confederate soldiers were firing at the mass of humanity trying to escape across the Potomac. Troops scrambled into the few boats available, which soon disappeared after the men in them were shot down by the Rebels. A large scow, which had carried over the two newly arrived companies of the 42nd, was overloaded with soldiers as it made its way back to Harrison’s Island and capsized, drowning most of its occupants.

Despite the confusion and death at the river’s edge, many Federals managed to get across to Harrison’s Island. Devens ordered his men to discard their guns and swim for the island. Other officers ordered the same thing. Some of the men who had been issued new Enfield rifles strapped them to their backs as they attempted to swim for their lives. Some made it. By 8 pm most of the Federals still remaining at Ball’s Bluff surrendered.

Upon hearing of Baker’s death, Stone quickly sent word to McClellan and rode from Edwards Ferry to Harrison’s Island. There he discovered the disaster that had overtaken his right wing. Ordering Colonel William Hinks of the 19th Massachusetts to hold Harrison’s Island at all cost until the wounded had been evacuated, Stone rode hard for Edwards Ferry, fearing the Rebels would attack them next.

Stone sent word to McClellan of the defeat at Ball’s Bluff and of his intent to evacuate Edwards Ferry. McClellan, however, ordered Stone to hold his position. McClellan promptly dispatched Banks’ division to reinforce Stone at Edwards Ferry. Stone also sent word to McClellan proposing that McCall be sent from Dranesville to Goose Creek. Stone was soon to learn that McCall had not been there all day. The reinforced Federals would not stay long at Edwards Ferry. The last Federal units withdrew on the morning of October 24.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff was a decisive victory for the South. As for the North, it was its second major defeat in northern Virginia. Of the 1,700 Federal troops who were engaged, 553 were captured and 400 were killed or wounded. The South, with roughly the same number of troops engaged, suffered approximately 200 casualties.

A shocked North wanted an answer for the defeat at Ball’s Bluff, as well as the earlier debacle at Bull Run. A Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was formed, and it quickly targeted Stone. The committee preferred to blame Stone for the disaster rather than Baker, who was a fellow politician. Stone defended himself by stating that he would have withdrawn from Virginia had he known that McCall was not at Dranesville.

Stone placed the blame for the defeat squarely on Baker, whose discretionary orders at Harrison’s Island were not to fight if the Rebels outnumbered him. This did not sit well with the committee, press, or radical Republicans, all of whom sought a scapegoat. Stone was arrested, although he was never formally charged. Stone was accused of being disloyal and incompetent, among other things. He spent six months in prison before being released.

In early 1863, Stone appeared before the committee a third time. He refuted the accusations against him, but his military career was severely damaged. He would serve until September 1864, at which time he resigned from the army. By that time the catastrophe at Ball’s Bluff had been overshadowed by much greater events in the long and terrible war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments