By John Mancini

On the night of August 19, 1943, a lone British Handley Page Halifax bomber flew over Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. The aircraft carried OSS Marine Captain Walter Mansfield. The 32-year-old Harvard graduate had been personally recruited by General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) that was the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency, from his own law firm.

A Rendezvous with the Chetniks

Mansfield’s assignment was to parachute into enemy territory near Belgrade and make contact with General Draja Mihailovich and his Chetnik guerrillas. This would be the first American military mission into Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. The objective was to get Yugoslav resistance units to provide support for the approaching Allied invasion of Italy by increasing pressure on the Germans and creating a strategic diversion for the enemy’s divisions stationed in the Balkans.

Captain Mansfield’s personal account reports, “After a five hour trip from Derna, North Africa, we spotted signal fires and made a pass over a field. I could see the fires beneath the jump hole. As soon as we checked our flash signal with the one seen on the ground, we did a circle of about 10 miles and came back. I shook hands with the RAF dispatcher, gave a thumbs up signal and when the light went green, shoved off. When the chute blossomed, I immediately saw the fires and realized that I was off to one side.”

Captain Mansfield continued, “I landed in a pile of rocks and slightly hurt my hip. I found myself on a cool mountainside and in a few minutes was surrounded by a group of bearded Chetniks who tried to smother me with kisses, yelling, Zdravo, Purvi Amerikanee! Greetings, first American! I signaled the pilot with a light that all was okay. The plane circled and dropped 15 containers of supplies, dipped its wings and disappeared into the night.”

A several-hour hike into the rugged, forested mountains brought Mansfield to General Mihailovich. The bearded, medium-built guerrilla leader and his Serbian Chetnik fighters were veterans of the Royal Yugoslav Army. They had refused surrender to the Nazi invaders after their defeat in April 1941, and they had remained loyal to the prewar government.

The Chetniks (“armed company” in Serbian) had established a primitive but extensive base camp only three hours away from German forces. The camp held several hundred fighters and served as a command and control headquarters for guerrilla bands operating throughout southern Yugoslavia. Mansfield was impressed with the organization, discipline, and morale of the guerrillas despite the harsh living conditions. However, military justice was swift and brutal. He reported, “Two spies were captured, and I had the unpleasant experience of seeing them get their throats cut.”

Sabotaging German Rail Supply

Several weeks after his arrival, Mansfield was awakened by machine-gun bursts and the crackle of rifle fire. Muzzle flashes pierced the darkness and ground fog. He grabbed his weapon and joined the fight. Ghostly figures emerged from the early morning mist. An estimated force of 200 German infantry had slipped past outposts, penetrated the Chetnik defenses, and was attacking the main camp. Mansfield picked targets and squeezed off rounds as Germans surged toward hastily formed Chetnik skirmish lines.

Sounds of gunfire, yells, and screams echoed through the thick forest as the two forces intermingled in fierce combat. After 15 minutes of savage fighting, the gunfire became sporadic and then stopped as the Germans broke off contact and silently withdrew. But they knew where the camp was, and the Chetniks knew they would be back.

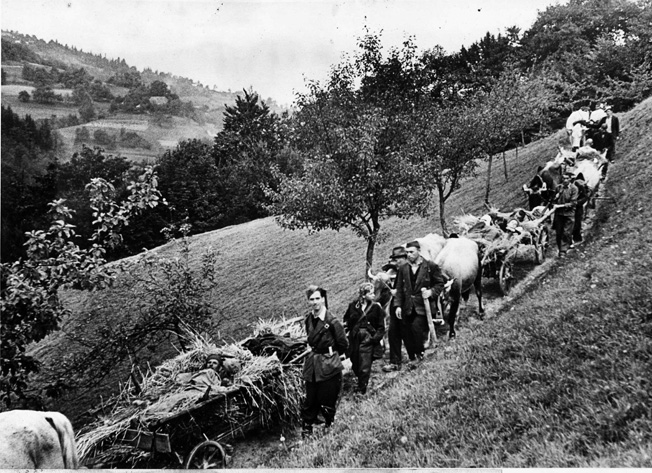

General Mihailovich immediately ordered an evacuation. Within several hours, 500 Chetnik fighters were on the move. A heavy rain fell as the single-file column trudged into the steep, dreary Serbian mountains. The guerrillas maintained a grueling pace through extremely rugged terrain in freezing rain for the next 15 hours.

The general finally halted the column near a small village in the Zlatibor Mountain range after patrols reported no threat of German pursuit. The guerrillas prepared for a major strike on the enemy in this region. Their objective was to disrupt the traffic on the major railway between German headquarters in Belgrade and a supply point at Dubrovnik on the Adriatic Sea.

The route contained several tunnels and a bridge. Mansfield and a British SOE (Special Operations Executive) officer led a reconnaissance patrol to assess the line and determine train schedules. They observed that the rail line was unguarded, but an estimated force of 500 enemy troops was stationed three miles from the targeted tunnel.

At about 4 pm, Mansfield and five men entered the tunnel, which was located one mile from the bridge. Chetniks were also positioned at each entrance. Mansfield and his team were busy placing half-pound blocks of TNT under the rails when they heard frantic yells from guerrillas stationed at the west entrance. A train was fast approaching the tunnel, one hour ahead of schedule. Mansfield and his force dashed from the tunnel, scrambled into the nearby forest, and waited for an explosion.

They fought disappointment as the train appeared at the tunnel entrance and stopped. Chetnik scouts raced from hilltop lookout posts and reported to the bridge detail that the train had made it through the tunnel and appeared undamaged. The British officer at the bridge immediately ignited well-placed explosives that severed the structure at both ends. A Chetnik patrol returned to the tunnel and discovered that Mansfield’s demolitions had in fact destroyed some track. The sabotage did cause a major disruption of enemy rail traffic. The German maintenance yard was on the opposite side of the destroyed bridge, which delayed the repair effort.

Escape from Yugoslavia: Gestapo in Hot Pursuit

Yugoslavia was a culturally, ethnically, and politically diverse country that consisted of six republics, four languages, and three religions. This environment resulted in the emergence of another guerrilla leader in northern Yugoslavia. He was a fierce threat to the Germans but had a very different political motivation and long-term agenda. Josip Broz, known as Tito, was a dedicated communist with allegiance to the Soviet Union. Intense competition erupted between Tito and General Mihailovich for Allied support.

The British were shifting their aid from the Chetniks to Tito’s Partisans. Radio messages from the OSS Cairo Station to Captain Mansfield requested more intelligence analysis regarding which resistance group deserved American assistance. During the months of November and December 1943, Mansfield traveled the rugged north central region of Serbia assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the Chetnik units.

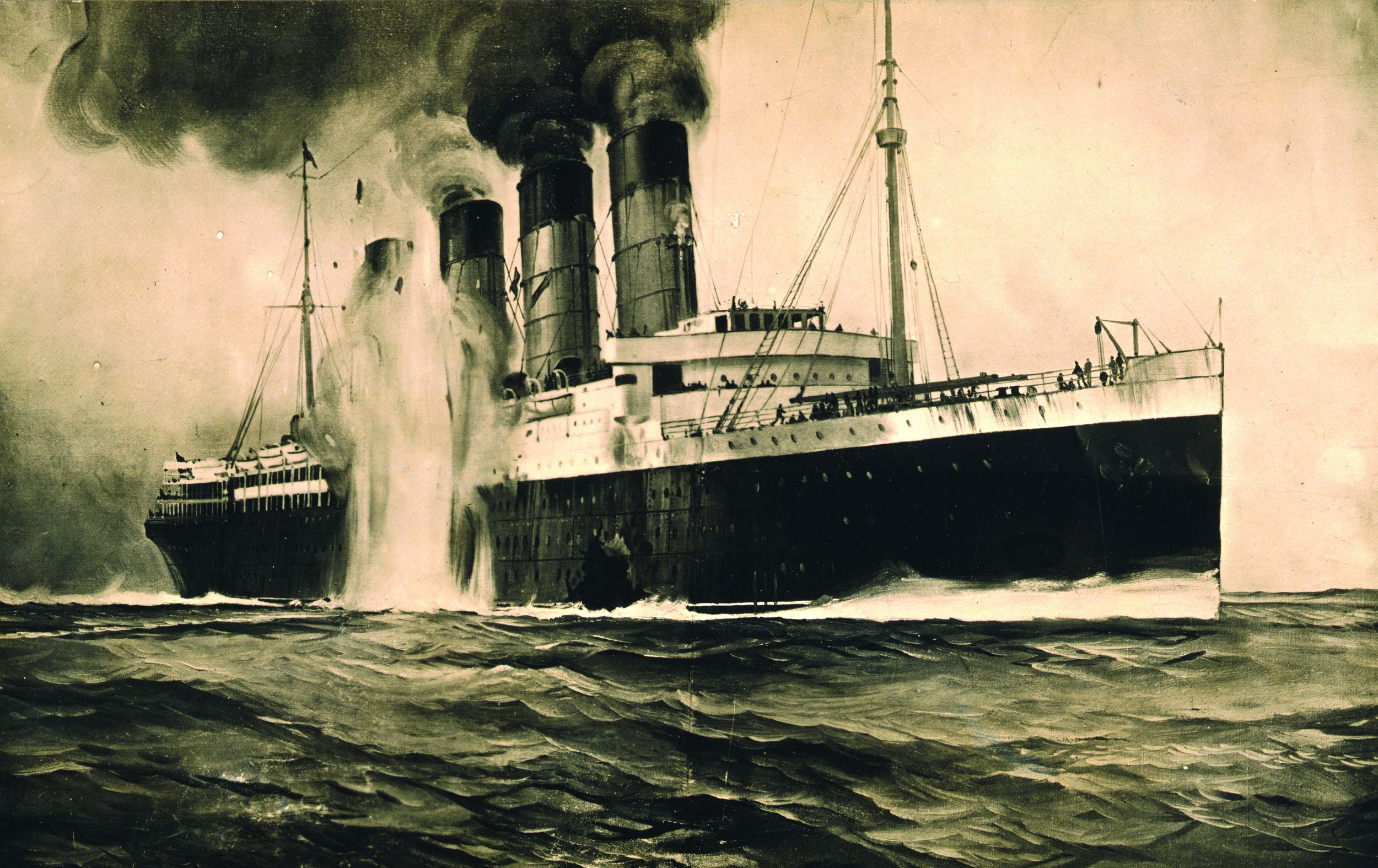

By the end of December, heavy winter snows had fallen and Mansfield faced the grim realization that German troops blocked his return to General Mihailovich’s main force. He decided that it was time to leave Yugoslavia. For the next several weeks he evaded aggressive enemy patrols and hiked 200 miles to the Dalmatian Coast where he planned to sail across the Adriatic Sea to Italy.

Mansfield arrived at the coastal town of Dubrovnik in January 1944, with German troops in hot pursuit. Mansfield also received chilling news from the local resistance leaders who reported that the Gestapo already knew that an OSS agent was in the city. Resistance fighters took great risks to hide him. Every night he was moved from one safe house to another. He also faced the harsh reality that there was no easy way to get across the Adriatic to Italy. The Germans maintained tight control over all boats and operated aggressive air and sea patrols.

As Mansfield struggled to suppress frustration and avoid capture by the Gestapo, he was encouraged by meeting a British agent with a radio transmitter. The radio could be used to contact Cairo Station and request a sea extraction. The only immediate problem was a dead battery. However, the resourceful guerrillas took great risks and obtained a new radio battery.

The two covert operatives waited until a scheduled contact time and began a telegraph transmission. Since neither agent had communicated with Cairo headquarters for several weeks, they feared their message could be viewed as enemy controlled. Their apprehension quickly disappeared as the clicking telegraph key gave instructions for an extraction. They were directed to be at a designated rendezvous point in two nights and begin flashing a signal light at 10-minute intervals between 8 pm and 1 am.

Unfortunately, the weather turned bad. Roaring winds turned the sea into foaming 30-foot waves crashing along the rocky coast at the rendezvous point. Mansfield waited on the shore of a small isolated cove, periodically flashing the signal into the pitch black darkness. At 2 am he admitted that the gale force winds and thundering surf prevented a rescue that night.

The Allied agents would have to continue their deadly cat and mouse game with the Gestapo a while longer. The two men were hidden by the guerrillas in the attic of a house located in a small coastal town that was heavily occupied by German troops.

Several nights later, the two agents and several guerrillas slipped back to the pickup point. They again began flashing signals into the dark night. Within 20 minutes they heard the sound of an engine. Could it be a German patrol boat? Despite the risk, they continued to flash the signal. Minutes later a wooden dinghy appeared and transferred them to a British patrol boat for the trip across the Adriatic Sea to safety in Italy.

From Europe to the Asia: Mansfield is Deployed to China

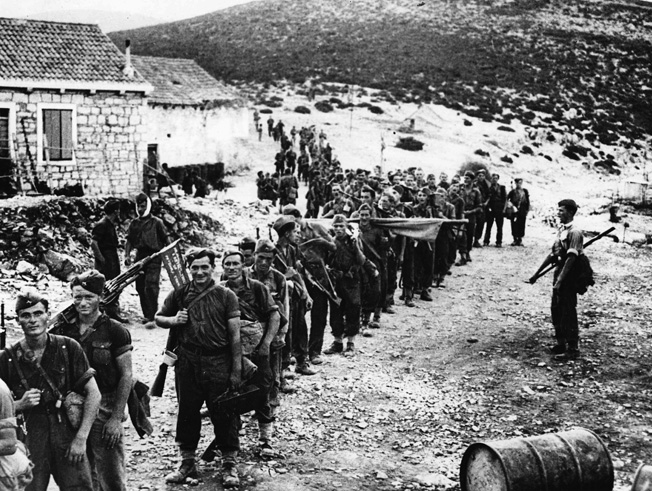

Mansfield’s next OSS mission would take him to China where he would train and lead guerrillas behind Japanese lines. He arrived in China in December 1944. He was to lead guerrillas on raids and sabotage Japanese plans. These operations had the strategic objective of keeping large numbers of Japanese troops busy on the Asian mainland so they would not be deployed to the Pacific island fighting. OSS agents in China were also confronted with complex internal problems while trying to mount action against the Japanese.

Like Yugoslavia, China had two competing political forces, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Tse-tung’s Communists. The two groups fought each other for control of China, and occasionally with OSS leadership they also fought the Japanese. The conflicting political factions and warlords had their own agendas in which fighting the enemy occupiers was not always the first priority.

Captain Mansfield immediately began to organize, train, and lead a guerrilla force to harass and disrupt Japanese supply lines in Hunan Province. The goal was to hit part of the enemy strategic communication route that stretched from the seaport of Hong Kong to north China and the city of Pieping (Beijing).

Mansfield and his six-man team traveled 800 grueling miles in trucks and then on foot from OSS headquarters in Kunming to the headquarters of the 74th Chinese Army at the ancient walled city of Wukang. The OSS team spent the next three weeks training 300 Chinese soldiers in the use of basic infantry tactics and weapons.

Finally, Mansfield led the Chinese fighters into Japanese-controlled territory. The single-file column marched for 15 days over steep, winding mountain trails and through snow-covered rice paddies to the headquarters of the regional guerrilla chief.

A Warm Warlord’s Welcome

The chief gave Mansfield’s force a warm welcome. However, it became apparent that the guerrilla leader was interested in acquiring American equipment and wanted to fight the Japanese only to obtain weapons and supplies to strengthen his position as a local warlord. Mansfield provided several days of training in the use of the Thompson submachine gun, demolitions, bazookas, firing devices, and pocket incendiaries.

When the training was finished, Mansfield reported, “I pressed for action, suggesting several targets that I would like to see his men pull off warranting our request for more supplies. We finally worked out a plan for a major ambush on a Jap convoy on the Heng-yang-Siangtan Road, to be combined with blowing up a 30 meter bridge. Intelligence reports showed large convoys of 30 to 100 trucks passing down the road at night, protected by tanks and truck-borne soldiers, despite heavy snow. We started out in heavy snow—the first in 20 years—a group of about 500 men. The Chinese colonel brought along a sedan chair and often hopped in for a spell while we walked. When we got about 40 miles east we ran into about 200 Japs. Both sides started firing. We withdrew leaving the second in command in charge. He joined us a while later and reported 27 Japs killed. A report came in that no convoys were running on the road because of the snow.”

Mansfield continued, ”We learned that the bridge was probably unguarded because of the snow. So, I proposed that we blow it. The bridge was wood, supported by eight pillars about one foot in diameter. I calculated charges and prepared them. The plan was for me to go with the Chinese to a point a couple of miles away. They would go on disguised as civilians. At 2100 hours they blew it. You could hear the boom for miles as we got away. Everyone reported there was nothing left.

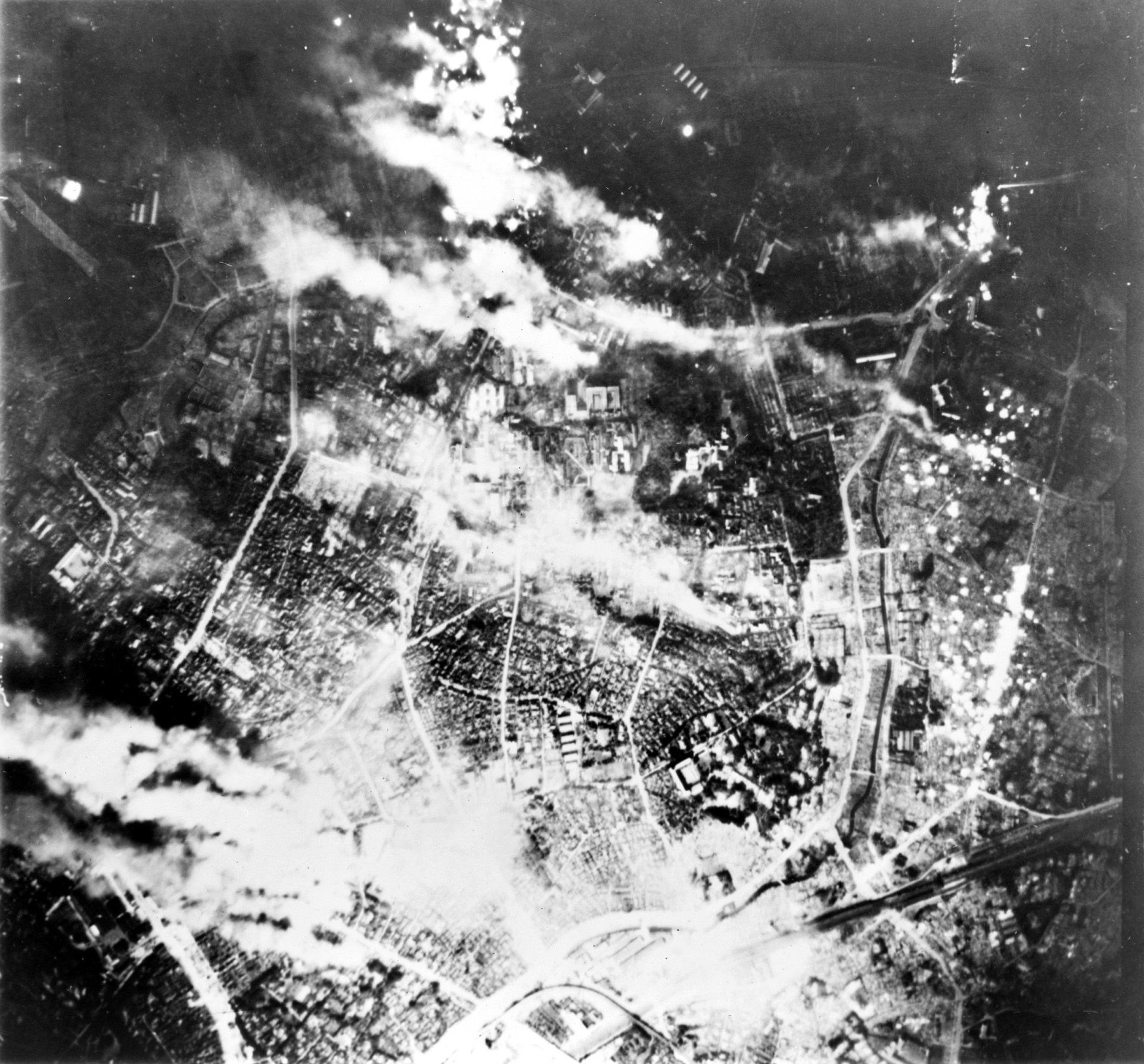

“Two Chinese guerrillas reported that there was a Jap truck depot where 300 trucks were parked. The trucks were camouflaged in woods with a repair shop and warehouse nearby. It was supposed to be too heavily guarded for a guerrilla attack. I decided to get close with a radio and a small group to make a reconnaissance for the purpose of calling in and guiding Yank 14th Air Force bombers, if they would come. The first day of the recon we pooped up and down steep hills. I finally got to a hill where I had a perfect view of the woods. I could see Japs but no trucks. We ran into a small Jap patrol that started firing and chased us, but we got away.”

The next day a Chinese officer dressed in peasant clothes was able to get near the staging area for a closer look and reported seeing approximately 100 trucks, but the Japanese had been alerted to guerrilla activity in the area and kept Mansfield and his men on the run. Despite the risk, he was able to send a radio message and arrange for a bombing strike.

Mansfield describes the scheduled air attack. “The day started out with good weather, but then closed in. When it cleared again I started out for a hill almost on top of the target.” He and several Chinese guerrillas ”lay between rocks with a perfect view of the target 1,200 yards below.”

The bombers arrived 10 minutes after Mansfield was in position and conducted a 15-minute attack, which missed the target. Mansfield waited for another strike until 4 pm. His spirits rose the following day, and he reported “the bombers came over again and bombed the Hell out of our target for a long time.”

A Cold Ambush

On a cold, overcast day in March 1945, Captain Mansfield executed a major ambush on a large Japanese force. The trap was sprung in daylight near an enemy garrison. His guerrillas fanned out across a hill and took up firing positions behind rocks and shrubs overlooking the main access road. The OSS force waited silently in biting cold for several hours. The absence of visible enemy activity fueled apprehension. Several of Mansfield’s Chinese officers feared that the enemy had spotted them and were circling in behind.

Just as Mansfield was preparing to give the order to withdraw, he spotted movement down the road. Squinting through his binoculars, he saw a column of approximately 100 Japanese infantry marching toward his position, led by an officer with a gleaming sword. Tension grew as Mansfield and his guerrillas waited for the enemy to get into their kill zone. The distance closed to 80 yards, and his Chinese lieutenants whispered with urgency, ”Chenzai! Now!”

Mansfield replied, “Meyo! No!”

The combat-seasoned OSS Marine held his command to fire for a few more agonizing minutes. When he could see the enemy’s faces, he signaled his men for action. Shrill whistles blew. Mansfield sighted his Thompson submachine gun on the center of the column and squeezed off a lethal burst.

Ten Japanese soldiers were slammed to the ground by the deadly barrage of machine-gun and rifle fire. The Japanese were well trained and reflexively ran for cover in the roadside ditches. Mansfield sprinted among the guerrillas to direct more effective fire on the Japanese positions. He knew they would have to finish the fight quickly before reinforcements rushed from the nearby garrison.

After a violent 25-minute firefight, Mansfield’s force came under heavy mortar attack from a Japanese relief unit closing fast on the guerrillas. He decided it was time to go and signaled for withdrawal. Despite poor Chinese fire discipline and marksmanship, 80 enemy soldiers were killed. The ambush force left the area with two prisoners, numerous captured weapons, and a Japanese officer’s sword “appropriated” by Captain Mansfield.

Night Attack on a Japanese Convoy

The American operative’s command maintained the pressure on the enemy with a night ambush. He reported, “At 2000 hours we placed 250 men alongside of a hill about 150 yards from the road and waited in the dark. One Jap convoy passed, and I counted 32 trucks. They were traveling very slow, about 10 miles an hour with headlights on, about 50 feet apart. I could clearly see the drivers and some soldiers in the backs of the trucks. The drivers were calling out to each other, apparently trying to keep together. We decided not to attack because there were too many Jap soldiers. We waited and about one half hour later another convoy of 30 trucks approached.

“We got ready, and when the first truck passed and was about 75 yards from the bazooka hideout, the bazooka fired, hitting the truck dead in the middle, throwing off a great flash of metal sparks in all directions. This was the signal, and all hell broke loose as the Chinese sprayed the convoy with our light machine guns, Tommy guns and rifle fire. All the other trucks instantaneously doused their headlights, and soon Jap firing started from the other side of the road, but the Japs were firing their little popguns, and I saw no Jap machine gun flashes. The bazooka continued to fire at other trucks, and a very heavy fight went on for about 45 minutes. I was told that Jap reinforcements were coming up the road, so we retired. Upon reaching our temporary headquarters about four miles back, our men began to appear. We then marched another 10 miles through paddies and hit the sack at 0300 hours.”

The following morning, the Chinese reported to Mansfield that 120 Japanese had been killed in the ambush. Many rifles were captured, but no prisoners were taken.

Mercy Missions: Rescuing POWs in the Pacific

Captain Mansfield led guerrilla operations in this sector behind enemy lines from February to May 1945. During this four-month period the daring OSS Marine chalked up an impressive record of successful missions that included training approximately 800 Chinese soldiers and guerrillas, inflicting hundreds of casualties, and destroying major bridges and thousands of feet of telephone line. After the Japanese surrender he participated with OSS mercy teams, whose mission was the rescue of Allied prisoners of war from Japanese camps in North China and Manchuria.

There was evidence that high-ranking Allied officers, such as General Arthur Percival, the former British commander of Singapore and American General Jonathan M. Wainwright, who had surrendered at Bataan in the Philippines in 1942, were being held in Japanese camps. There were also still over a million Japanese troops in North China and an entire Army group in Manchuria. Mansfield was assigned to one of nine teams organized for rescue and humanitarian operations. These six-man mercy missions were similar to the contact teams used in Europe to assist in the liberation of German POW camps.

After his extraordinary tour of duty with the OSS in Yugoslavia and China ended, Mansfield quietly returned to the United States and the practice of law.

Amazing!