By Eric Niderost

Captain William Tennant stood on the deck of the Wolfhound, grimily observing the progress of a German air raid as his ship approached Dunkirk. The port city in the northeast corner of France, which was not far from the Belgian border, was being brutally pulverized before his eyes. Bombs detonated, sending up fountains of smoke and debris, smashing buildings, and killing and wounding French civilians unlucky enough to be on the scene.

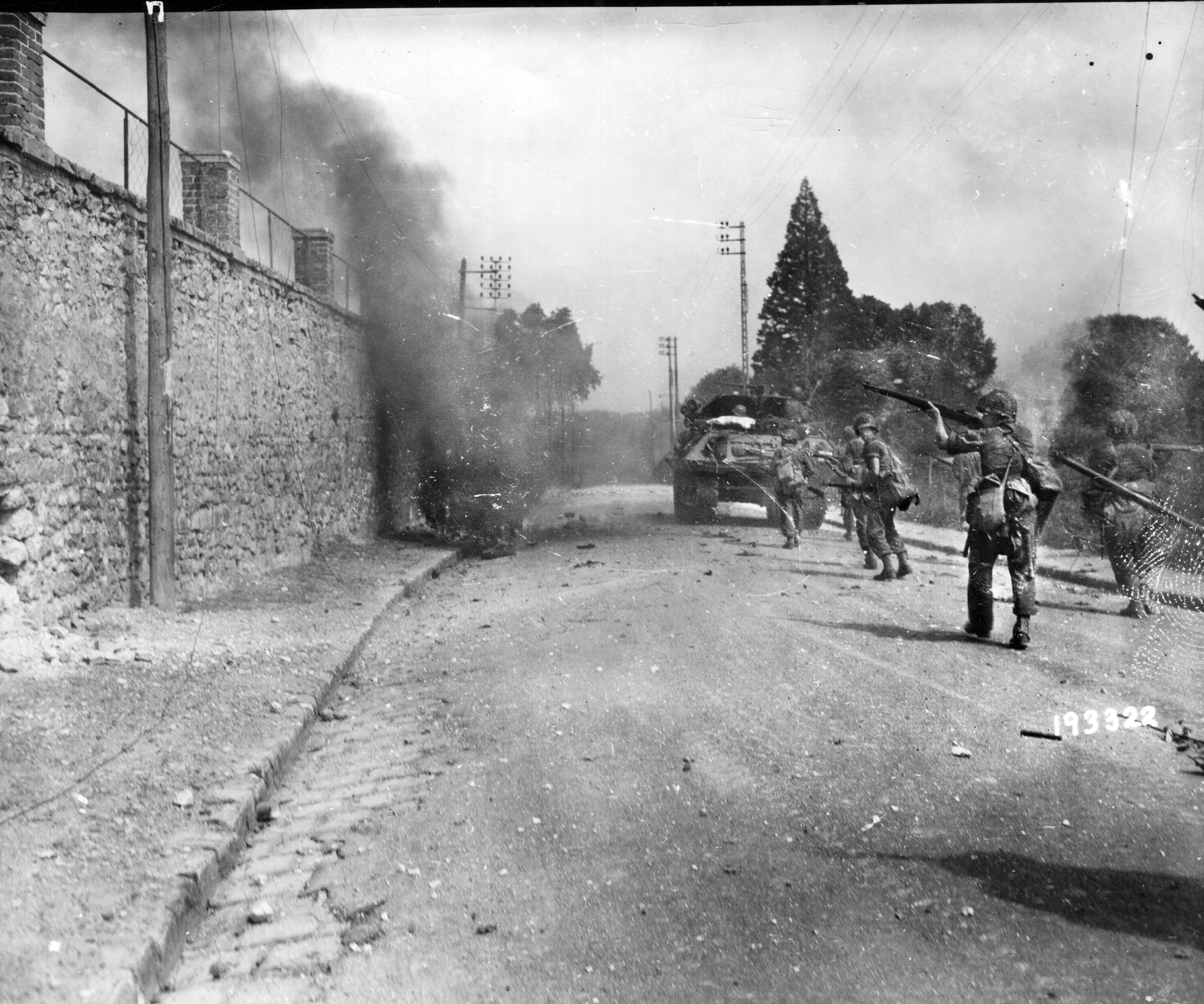

Fires erupted from different parts of the stricken city, merging until the whole port seemed engulfed in flames. But it was the burning oil tanks, hit earlier in the day, that commanded the most attention. Great columns of acrid smoke rose into the sky, the black and choking clouds so thick they obscured the normal blue of a bright spring day. It seemed a funeral pyre of British hopes, mocking their plans to escape the German juggernaut.

Tennant was on a special assignment, a mission that might well decide the outcome of World War II. The British and a portion of their French allies were trapped by superior German forces and faced with annihilation or capture. If they escaped, then the British Army would survive to fight another day. If not, well, Tennant was not going to waste his time on defeatist speculation. He had a job to do, and he meant to do it well. It was May 27, 1940, and Operation Dynamo, the rescue of the British Expeditionary Force, was shifting into high gear.

Tennant officially was senior naval officer ashore, ordered by his superior, Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, to supervise the evacuation and coordinate all the elements that were needed to achieve that end. Originally Dunkirk seemed like a perfect embarkation point. There were no less than seven docking basins, five miles of quays, and 115 acres of docks and warehouses. Pouring over maps and other related documents with his staff, one of Tennant’s main concerns was turnaround time. The challenge was to figure out how destroyers and other craft could nose into the quays, fill with troops, and depart fast enough for other ships to quickly take their place.

But in his mind’s eye he could see those plans going up in smoke, just as surely as the hoped-for quays and docks were blazing and sending their own black coils into the heavens. Tennant was accompanied by a dozen officers and 150 ratings. Since Wolfhound was an obvious target the shore party was landed and dispersed.

Tennant himself set out for the British command post. What was normally a 10-minute walk was a nightmarish hour-long journey through rubble-filled streets. Downed trolley wires festooned the avenues, burned-out vehicles were everywhere, and corpses of both British soldiers and French civilians sprawled about like bloodied rag dolls. A kind of thick, smoky haze enveloped everyone and everything, reminders of the oil fires that still blazed fiercely.

The Royal Navy officer finally arrived at Bastion 32, an earth-covered bunker that served as British headquarters in Dunkirk. He was greeted by Commander Harold Henderson, the British naval liaison officer, and representatives of the British Army. But there was one question that must have been paramount in his mind: How long would he have to do the job? In other words, how long would it be before the Germans arrived? The answer was swift and discouraging: 24 to 36 hours.

The task before him seemed impossible, but Tennant was a professional who was determined to do his duty to the best of his ability. The coming days would determine not only the course of the war but the fate of Britain itself.

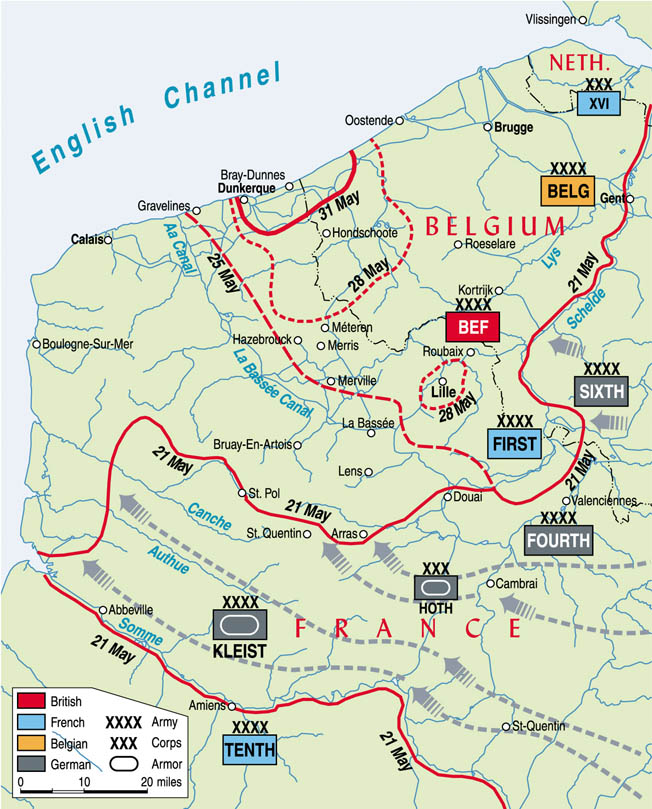

The Dunkirk crisis began on May 10 when the Germans unleashed their blitzkrieg attack in the west. The operation, code-named Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), had two distinct phases. General Fodor Von Bock’s Army Group A, which totaled 29 divisions, suddenly thrust into Holland and Belgium. To the Allies, these moves were reminiscent of the old Schlieffen plan used the early weeks of the World War I. Although Holland’s neutrality was not violated in 1914, in other respects it looked as if the Germans were attempting to repeat history by thrusting into Belgium and turning south into northern France.

The Allies countered with a lackluster effort known as Plan D. In this scenario, the BEF and the French First and Seventh Armies would advance to Belgium’s River Dyle and dig in on its left bank. The Dyle was a good defensive position and would be an effective deterrent to any German attempts to move south.

The relatively weak French Second and Ninth Armies were posted farther to the southeast in the heavily forested Ardennes region. The area was thought to be safe because the densely forested hills and deep ravines were considered poor country for tanks. South of the Ardennes was the vaunted Maginot Line, a formidable, at least on paper, series of concrete and steel fortifications. It was manned by 400,000 first-rate troops. France had been bled white by World War I, and over time there was a misplaced faith in big guns and fixed fortifications, an attitude described as the “Maginot mentality.”

But the Germans had no intention of repeating 1914, nor were they going to waste lives trying to smash their way through an impregnable Maginot Line. Army Group A’s descent on Holland and Belgium was in part a ruse, diverting Allied attention from the main German thrust through the supposedly impenetrable Ardennes. If all went well, the 45 divisions of General Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group A would punch through the Ardennes, cross the Meuse River, then drive to the sea.

If the Germans managed to get to the sea, they would effectively drive a wedge between the BEF and the First French Army in the north and French forces operating south of the Somme River. A panzer corridor could widen, making it harder for the separated Allied armies to reunite. At the same time, the BEF, northern French units, and possibly the Belgian Army would be trapped between Group A’s panzer “hammer” and Group B’s formidable “anvil.” The German planners believed the two powerful army groups could destroy the Allied forces.

There were no fewer than seven panzer divisions with Rundstedt’s Army Group A, a veritable mailed fist of 1,800 tanks. Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel, a commander who would later gain immortality in North Africa and earn the sobriquet Desert Fox, commanded the Seventh Panzer Division. But as events unfolded it was Lt. Gen. Heinz Guderian who took center stage in this effort. Guderian commanded the XIX Panzer Corps, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, and 10th Panzer Divisions, and had long been a proponent of armored warfare.

From the first the Germans achieved a stunning success. Group A’s panzers successfully negotiated the forested slopes and rocky defiles of the Ardennes. They then advanced to the Meuse River where they established a bridgehead. Taken by surprise, the French tried to dislodge the intruders and throw them back across the river, but their attacks were half-hearted at best and ham-fisted at worst.

Some French soldiers fought courageously, but others were so demoralized they surrendered at the first opportunity or simply took to their heels. French generals, fossilized in their military thinking and often ancient in body, simply could not cope with this new style of rapid warfare. General Alphonse Joseph Georges, for example, was commander of the northeast sector, and technically the BEF was under his control. When news came of the German breakthrough he literally collapsed into a chair and began weeping uncontrollably.

Guderian and his tanks were having a field day; opposition was either nonexistent or simply melted away. The French Ninth and Second Armies were pummeled unmercifully until they were effectively destroyed. General Edouard Ruby, deputy chief of staff of Second Army, movingly described the bombing by high-level German Dornier 17s and dive-bombing Stuka Ju-87s as nightmarish. Then, too, there was the terror of continued panzer assaults, with hulking metal monsters belching shells, their treads steamrolling over defensive positions with almost scornful ease.

Thousands of French soldiers shuffled to the rear as prisoners of war. Many of them were dazed automatons, their nerves shattered by relentless Stuka attacks and the sheer magnitude of their defeat. Scarcely glancing at these pitiful poilus, the German tanks sped on, at one point covering 40 miles in four days.

General John Vereker, 6th Lord Gort, was the commander in chief of the BEF. A no-nonsense professional, he was no military genius but was competent and very protective of Britain’s only field army. Communications between Gort and his French allies had almost entirely broken down. It was partly because of the rapidity of the German advance, and partly due to the sheer stupidity of the French high command.

When the war broke out in 1939, the French high command rejected the use of radio communication. Radio messages could be easily intercepted by the enemy, or so the argument ran. The French placed their faith in telephone communication, stringing lines with cheerful abandon, or using civilian circuits when possible. The British had little say in the matter; after all, they had only 10 divisions, the French 90 divisions.

But when the German blitzkrieg struck, all dissolved into chaos. The Germans cut lines, but overworked signalmen just could not keep up with the ever-changing situation. Roads were clogged with retreating units and fleeing civilians, making their task that much harder. At one stage Gort’s headquarters moved seven times in 10 days.

The only way to keep communications open was by personal visit or by motorcycle dispatch rider. Maj. Gen. Bernard Montgomery, who would gain later fame defeating Rommel in North Africa, had his own unique way of sending messages. At the time Montgomery was commander of the BEF’s Third Division. Riding in his staff car, he would place a message on the end of his walking stick and poke the stick out the window. Sergeant Arthur Elkin would roar up on his motorcycle, grab the message, and speed down the country lanes in search of the addressee. It was no easy task.

Gort had his first real inkling of the true situation when General Georges Billotte, commander of the French First Army Group, visited his command post at Wahagnies, a small town south of Lille. Billotte was normally an ebullient man, but now he looked exhausted and depressed. He spread a map out and explained that no fewer than nine panzer divisions had broken through at the Ardennes and were even then sweeping westward. Worse still, the French had nothing to stop them.

Although there is no specific evidence of the fact, Gort probably started thinking about withdrawing the BEF to the Channel ports about this time. A German trap was closing, and half-hearted French talk about countermeasures was not going to assuage his growing concern. Some of Gort’s senior staff began to plan for just such an operation in the early morning hours of May 19.

Back in London, Secretary of State for War Anthony Eden was dumbfounded when he heard the news that Gort might want to evacuate. Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Sir Edmund Ironside also was not too pleased. It seemed to Ironside like alarmist rubbish. In any case, why couldn’t the BEF escape the closing trap by driving south to the Somme and joining the French forces that were supposedly gathering there?

Winston Churchill, Britain’s new prime minister, tended to agree with Ironside. Churchill’s fighting spirit was aroused. But if the BEF managed to link up with the French forces south of the Somme, the Allies might then mount a counteroffensive and turn the tables on the rampaging Germans.

But Churchill was being overly optimistic. Gort knew the situation better than London. Most of the BEF was still engaged with German Army Group B to the east. For that reason, they could not just suddenly shift and charge direction without serious consequences. If they tried to move south, the Germans would have a golden opportunity to pounce on their flank and rear.

Ironside travelled to France to personally convey Churchill’s opinion to the BEF commander. The entire War Cabinet in London also concurred with the prime minister. Gort respectfully stood his ground, explaining how most of the BEF was fighting to the east. Ironside conceded the point but suggested a compromise: why not use Gort’s two reserve divisions for a drive south? The French agreed to support the effort with some light mechanized units.

Gort agreed to the proposal. He was sure the effort would be stillborn, but he was a good soldier who was not about to defy the prime minister and seemingly half the British government. Accordingly, a mixed force of infantry and tanks, labeled Frankforce after their commander, Maj. Gen. H.E. Franklyn, was assigned to attempt a breakthrough to the south.

The French also had a new commander in chief, General Maxime Weygand. The septuagenarian had a youthful energy and sunny optimism that dispelled the defeatist gloom that had sunk French headquarters into the depths of despair. Weygand impressed Churchill, grandly unveiling a Weygand Plan that envisioned eight British and French divisions, aided by Belgian cavalry, sweeping southwest to link up with French forces farther south.

But the Weygand Plan was based in fantasy, not reality. The situation was deteriorating rapidly, with Allied forces scattered, fully engaged elsewhere, or simply nonexistent. Weygand grandly issued order after order, paper salvos that might boost morale but did little to counter the German threat. General Order No 1, for example, directed northern armies to “prevent the Germans from reaching the sea,” but in point of fact they were already there and had been for several days.

In the meantime, Gort dutifully proceeded with his promised attack. Frankforce was a hodgepodge, hastily assembled collection of tanks, infantry, field and antitank guns, and motorcycle reconnaissance platoons. The cutting edge of the offensive was provided by 58 Mk1 and 16 Mk II Matilda tanks. The British Matilda was one of the best Allied tanks of the early years of the war. It featured armor up to three inches thick, and mounted a high-velocity 2-pounder gun.

The British Frankforce offensive began near Arras on May 21. It was spectacularly successful at first. Rommel’s Seventh Panzer Division was surprised and initially thrown into confusion by the sudden assault. Even Rommel himself, a man not prone to panic, thought he was being attacked by several divisions.

But perhaps the biggest surprise was the Mark II Matildas. The German 37mm gun, the standard Wehrmacht antitank weapon, was completely ineffective against the Matildas. It was said that one Matilda actually took 14 direct hits and yet emerged undamaged. On a literal roll, the British tanks advanced 10 miles before the Germans rallied and stopped the attack.

The British offensive was halted by a variety of factors. French support turned out to be weak or nonexistent. The British tanks had outdistanced their infantry and artillery support. But the Germans discovered they, too, had a surprise weapon. The 88mm antiaircraft guns turned out to be superb antitank weapons as well. The 88s of the German 23rd Flak Regiment were particularly effective against the British armor at Arras.

The British effort at Arras had been a forlorn hope. It was now Gort’s prime mission to save Britain’s field army. Soon contingency plans for the evacuation of the BEF were well in hand. By May 26, the BEF and elements of the French First Army were being squeezed into an ever-narrowing corridor 60 miles deep and 25 miles wide Most of the British were in the vicinity of Lille, 43 miles from Dunkirk; the French were farther south.

Luckily, British government officials, including Churchill, finally were starting to come to their senses. They had been mesmerized by hopes of victory and Weygand’s elaborate fantasies, but now the spell was broken. The BEF had to be evacuated or it faced sure annihilation. Churchill sincerely insisted that, as far as humanly possible, any trapped French troops also be rescued.

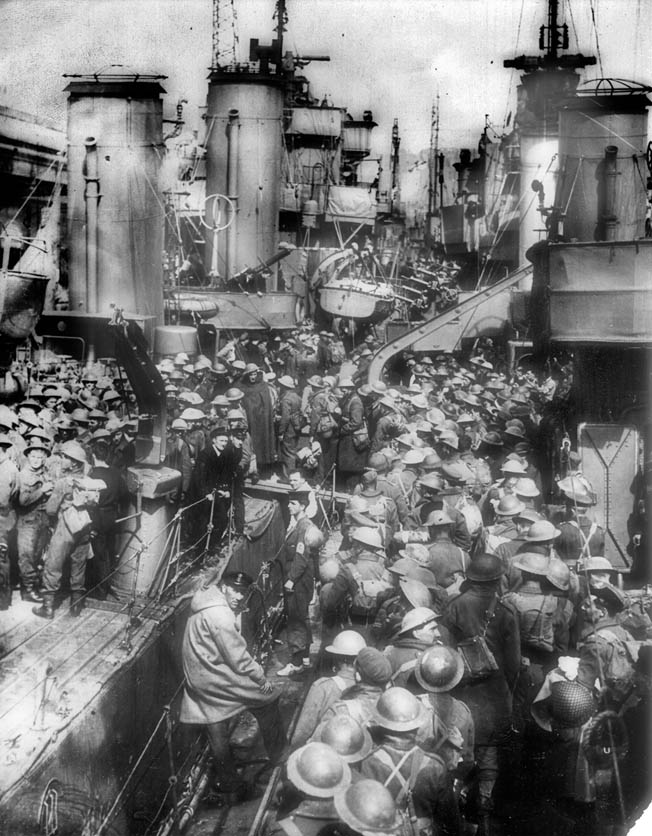

It was with a growing sense of urgency that Operation Dynamo was born. It officially began with the arrival of Mona’s Isle, a British troop transport, the evening of May 26-27. Luckily Ramsey, operating from his headquarters at Dover, had a wide array of resources at his disposal, including 39 destroyers, 38 destroyer escorts, 69 minesweepers, and a host of other naval craft.

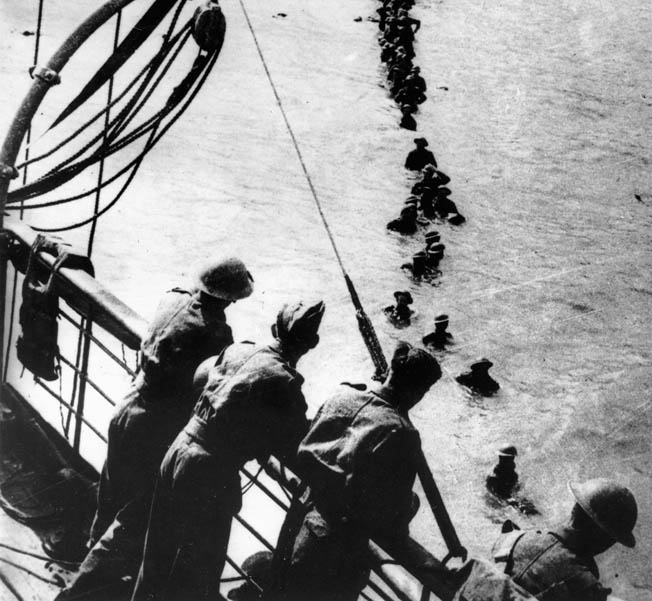

Tennant, Ramsey’s senior naval officer ashore, should see that the waters immediately in from of the Dunkirk beaches were too shallow for normal seagoing vessels. Even small craft could not get any closer than about 100 yards from shore, so the soldiers would have to wade out to their rescuers. Once the Tommies were aboard, the small boats would deliver them to the larger ships and then go back for another load.

Approximately 300 “little ships,” many of them scarcely more than boats, answered the call to duty. Every imaginable type of craft was used; if it could float, it passed muster. There were motorboats, sloops, ferries, barges, yachts, and fishing boats. Most of the civilians taking part were fishermen, but incredibly one boat was manned by teenage Sea Scouts.

But this shuttle system was taking too long in practice. Necessity is the mother of invention, and Tennant started thing about the moles. The West Mole was unusable because it was connected to the oil terminal and that facility was in flames. The East Mole, 1,600 feet long, was connected to the beaches by a narrow causeway. But the mole was a breakwater, designed to protect the port from raging seas. It was not intended to serve as a dock for shipping.

Tennant experimented a little, and it was found that ocean-going ships could indeed use the mole as a loading dock. The evacuation process was considerably accelerated, and more men could now be taken away.

In the meantime, land evacuation plans were firming up. With French cooperation, a defensive perimeter was established around Dunkirk and its immediate environs, a bridgehead that protected the port during the BEF’s evacuation. The generally marshy nature of the terrain helped the defenders, and man-made waterways like the Berg Canal were incorporated into the overall plan. Dikes were opened in certain areas, transforming these quagmires into shallow seas.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bridgeman, 2nd Viscount Bridgeman, was responsible for planning the perimeter. Methodical, clear-sighted, and hard working, he was so absorbed in his task that he was subsisting mainly on chocolate and whiskey. The perimeter would be about 30 miles wide and up to seven miles deep.

To buy time, strongpoints were established to slow the German advance. Gort had established a Canal Line that used the Aa Canal and La Basee Canal to guard the forward approaches to Dunkirk. British units held these strongpoints for as long as possible, fighting with dogged determination and stubborn courage, until they were forced to withdraw yet again.

The Dorset Regiment was holding a strongpoint at Festubert when it became clear that it was cut off and virtually surrounded. When they received orders to withdraw, they waited until nightfall to make the attempt. Colonel E.L. Stevenson, the battalion commander, had no maps but did possess a compass. His party included about 250 Dorsets and a ragtag group of odds and sods who had lost their units.

It was a pitch black; even the stars were shrouded by menacing dark clouds. At one point, Stephenson found himself confronted with a German sergeant who was out inspecting Wehrmacht outposts. Quickly drawing his pistol, he coolly killed the sergeant with one well-placed shot and motioned for the men to continue their trek.

Groping their way through the darkness, stumbling forward as best they could, the Dorsets suddenly came upon a road that barred their way. They had to cross this road to gain Allied lines, but at the moment it was filled with a convoy of German tanks and support vehicles rolling their way to some unknown destination. It looked like an entire panzer division was on the move, the Germans so confident they had their headlights blazing.

Stephenson and his men hunkered down in the shadows, hoping for a chance to cross the road. After about an hour the last vehicle passed, and the coast was clear. But the respite was temporary because another convoy of Germans could be heard rumbling up the road. The Dorsets scrambled across the road and hid in the underbrush just as the Germans came into view.

But the Dorsets’ odyssey was only just beginning. Guided by Stephenson’s trusty compass, they waded waist-deep through ditches stinking with garbage, groped though plowed fields, and crossed a wide and deep canal twice. They reached Allied lines around 5 am, dirty and exhausted, but triumphant.

The last few days had been a nightmare for the Allies, but the victorious Germans, perhaps a bit stunned by their own successes, were having their own set of troubles. Guderian’s panzers pushed on, with the Sambre River on their northern flank and the Somme on their left. On May 20 German tanks reached Abbeville at the mouth of the Somme, to all intents and purposes fulfilling their original mission. They had reached the sea and were the tip of huge panzer corridor that divided the First French Army and the BEF from French forces south of the Somme.

German panzers rumbled past bewildered French peasants, their treads kicking up clouds of dust plumes. They were followed by truckloads of motorized infantry, bronzed young soldiers who seemed to be in high spirits.

But now that they were on the coast, what would be the next course of action? At 8 am on May 22, the German high command sent a message in code Abmarche Nord. The plan now was to thrust north, taking the Channel ports and blocking the BEF’s last escape route. The Second Panzer Division would head for Boulogne, the Tenth Panzer Division for Calais, and the First Panzer Division for Dunkirk.

Lieutenant General Friedrich Kirchner’s 1st Division tanks set out around 11 am on May 23. Dunkirk was 38 miles to the northeast. By 8 pm that same day, advance units reached the Aa Canal, which was only 12 miles from Dunkirk. The waterway was part of Gort’s advance Canal Line defense, but at the moment there were relatively few Allied troops in the area to man it. Although Guderian and his advance panzer crews were in a state of euphoria, some senior officers were not so happy.

To Rundstedt, the long panzer corridor was far too vulnerable to counterattack. The panzers and motorized infantry were too far ahead of the unglamorous but vital regular infantry. It was the foot-slogging regular infantry what would shore up the corridor’s long and vulnerable flanks, not seemingly thin as an eggshell and liable to break under a determined Allied counterthrust.

The British attack at Arras had badly scared the Germans, who feared the Allies might be planning an even more powerful counterattack. The Dunkirk area was not really suitable for armor, which was something everyone knew. What is more, a few panzer units were down to 50 percent strength. Some were victims of enemy action, but many more were simply worn out and in need of maintenance.

Rundstedt ordered the panzers to halt, a decision that was supported by Fourth Army commander General Guenther von Kluge. Hitler concurred; he was becoming nervous about the French coastal areas, which he had known firsthand as a soldier in World War I. The land was boggy and cut by numerous canals and certainly not ideal for armor.

The action at Arras might have been abortive, but it did manage to scare the Germans into a mood of excessive caution. Suppose the Allies were planning a new thrust, a counterattack even greater than the one at Arras? It was a possibility that haunted both Hitler and his senior officers.

Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring now put in his bid for glory. He told the Führer his aircraft could finish off the British, in effect driving them into the sea. Hitler gave Göring the green light in part because his eyes were gazing elsewhere. The panzers still had to defeat the French forces south of the Somme. As for Paris, the prize that had eluded the Germans in World War I, the objective seemed well within Hitler’s grasp.

But after two days Göring’s assurances were shown to be empty bombast. The BEF was far from destroyed, so the Führer lifted the halt order. The panzers renewed the advance on the afternoon of May 26, but the Allies had been given two precious days to continue the evacuation.

Time was running out if the BEF was going to pull off a successful withdrawal. The Belgian Army capitulated on the night of May 27, a situation the Germans were bound to exploit. King Leopold III of the Belgians had protested that his army could do no more, but the surrender left the BEF’s flank dangerously open. For a time, only German uncertainty about a renewed advance prevented a British disaster.

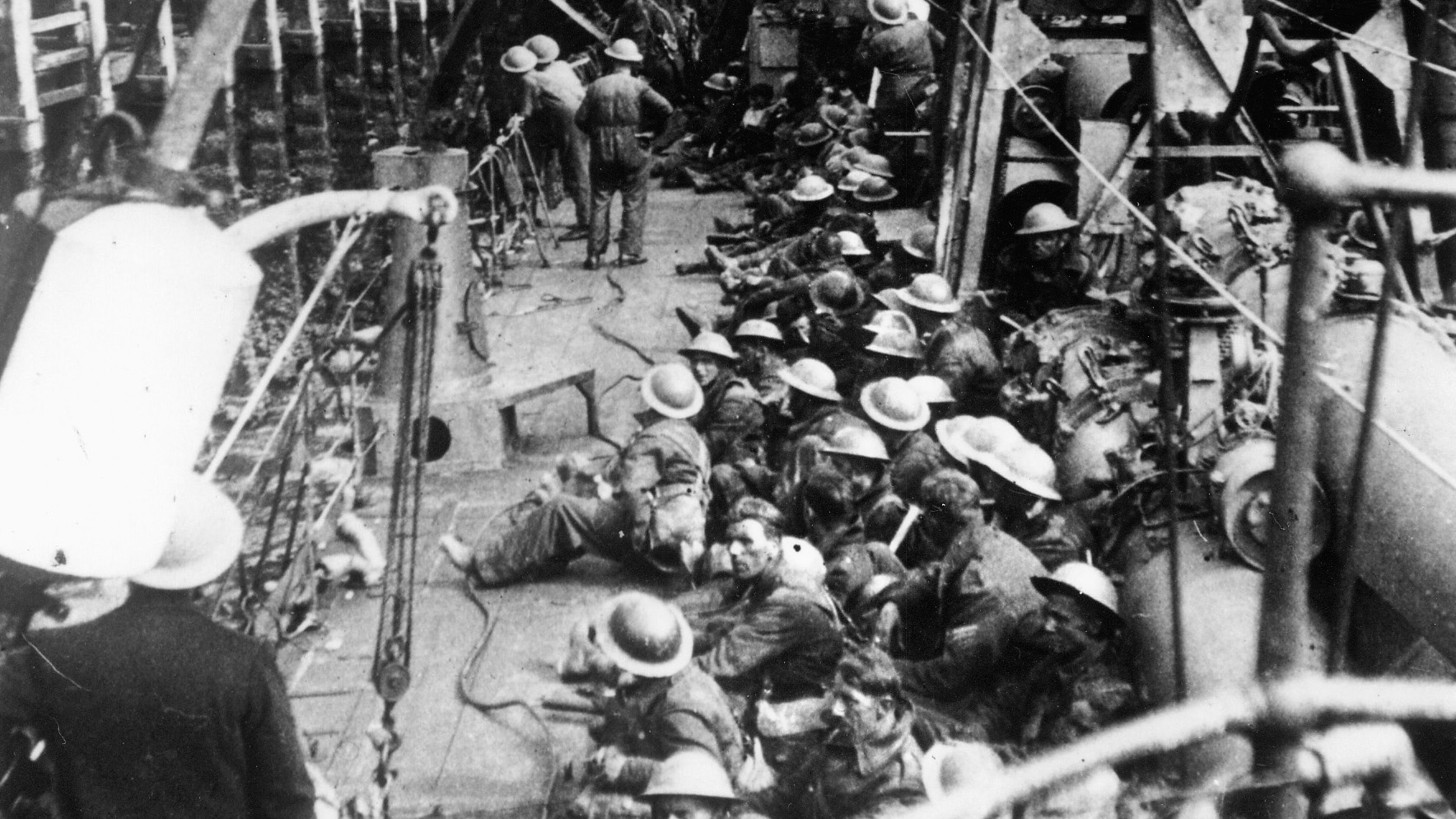

While Hitler and his generals debated, battered units of the BEF continued to arrive at Dunkirk. They had trekked for miles, their progress impeded by roads choked with fleeing refugee civilians. The Luftwaffe was having a field day, with German planes strafing civilian and soldier alike with cheerful abandon. Rations were scanty, and little food was found along the way. Fatigue was etched in their faces, and their battledress was dirty and soaked with sweat, but somehow they managed to put one foot in front of the other by sheer force of will.

Bridgeman had done his work well. To avoid unnecessary confusion, the three corps of the BEF were assigned specific debarkation sectors. III Corps would head for the beaches at Malo-les-Bains, a suburb of Dunkirk. I Corps would march to Bray-Dunes, which was six miles further east. II Corps was told to assemble at La Panne, which was just across the Belgian border.

BEF headquarters was at La Panne. The BEF had selected that location for its headquarters because it was the site of a telephone cable with a direct link to England. Lt. Gen. Sir Ronald Adam set up shop in the Maire, or town hall, of the seaside resort.

The bone-weary Tommies passed through the defense perimeter with a sense of relief, then entered a world that must have seemed almost surreal under the circumstances. Malo-les-Bains and the other towns were peacetime seaside resorts, where many French and Belgians had enjoyed summer holidays. There were bandstands where music once played, and carrousels where laughing children had ridden elaborately carved horses. Beach chairs lay scattered about and the colorful cafés still had stocks of refreshments.

The British soldiers seemed happy to be in this vacation spot and were going to make the most of it while they waited for deliverance. Dunkirk itself still blazed, the raging oil-fueled fires sending up columns of billowing smoke 13,000 feet into the air, but most of the troops were on the flat, sandy beaches that stretched toward the Belgian border.

German Stukas would appear occasionally, but after the terrors of the past weeks, some Tommies considered them more nuisances than objects of terror. The soldiers played games and swam, and some threw away their Enfield rifles and wandered aimlessly across the sands. Still others pilfered French wines and liquor and sat around the cafés chatting and drinking like tourists on holiday. One man even stripped to his shorts and sunbathed, contentedly reading a novel.

At times the German bombardment was more than just a nuisance, but the British had almost no antiaircraft guns because of a monumental mix up. In the original orders, spare gunners were to go to the beach, a directive that included wounded or incapacitated men. Maj. Gen. Henry Martin somehow misunderstood, thinking it meant that all gunners were to be evacuated.

Since all gunners were to leave, or so he thought, Martin ordered all his 3.7-inch artillery pieces to be destroyed, lest they fall into enemy hands. When Martin proudly reported to Adam that “all antiaircraft guns have been spiked,” the latter was incredulous. This was stupidity beyond words. Baffled and weary, Adam merely replied, “You fool, go away.”

Some Tommies complained that they saw little or nothing of the Royal Air Force. The RAF did its best, bombing enemy positions and sending up fighters during the daylight hours. At the end of Operation Dynamo, the RAF had lost 177 aircraft while the Germans lost 240. This was a foretaste of the Battle of Britain for the Germans, who were meeting an aerial foe equal, or in some cases, superior to them in equipment and personnel for the first time.

The English Channel, which is notorious for being capricious, “cooperated” with the British to a very remarkable degree. For nine crucial days it was flat calm, more like a millpond than a storm-swept waterway. This is not to say that passage to England was trouble free. Each route was in some way exposed to direct German attack or German-created hazards. Route Z was the shortest route, but it was within range of German batteries at Calais. Route X, to the southeast, avoided German artillery but was subject to shoals and mines. Route Y, which was 100 miles in a long, circuitous path, was subject to German air attack.

When their time came the British soldiers peacefully queued in long lines and walked into the surf. Arthur Divine, a civilian who was manning one of the little ships, remembered the British soldiers queuing up, “the lines of men wearily and sleepily staggering across the beach from the dunes to the shallows, falling into little boats, great columns of men thrust out into the water among bomb and shell splashes.”

“The foremost ranks were shoulder deep [in the water], moving forward under the command of young subalterns, themselves with their heads just above water,” said Divine. The BEF had no choice but to abandon all their equipment and vehicles, but some of the army trucks performed a final but nevertheless vital service. They were driven into the shallows and lashed together to form improvised jetties.

The evacuation would not have been possible without the sacrifice of British and French units outside the immediate Dunkirk region. Surrounded and under siege, the bulk of the French First Army held out at Lille until May 30. In the process, they managed to tie up no fewer than six German divisions. The First Army fought so well that the Germans granted them the full honors of war, including marching out into captivity preceded by a band playing lively martial airs.

The British garrison at Calais also performed heroically, although historians debate to what extent their defense held up the German advance. The Calais Force was led by Brig. Gen. Claude Nicholson and 4,000 men. Nicholson’s command included some well-trained regulars, the King’s Royal Rifle Brigade and 1st Rifle Brigade. There was also the 1st Queen Victoria’s Rifles and elements of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment

The Calais fortifications were outdated. The celebrated French engineer Vauban had designed some of the fortifications in the 17th century. Despite this defensive weakness, the garrison fought with great courage and tenacity for several days, but it finally succumbed to the enemy and surrendered on May 30. It probably bought some additional time for the evacuation process; given the crisis situation, every little bit helped.

Operation Dynamo continued until June 4, when it was clear French rearguard defenses were finally crumbling. Tennant sent a laconic but succinct message back to England: The official totals were gratifying. No fewer than 338,226 men were evacuated; of that number 139,000 were French. Earlier, more pessimistic estimates of the number of men rescued were as low as 45,000.

Great Britain was relieved that the BEF had escaped, but Churchill reminded the country, “Wars are not won by evacuations.” Still, the BEF was a professional core that future armies could be built upon. As one British newspaper put it, the deliverance at Dunkirk was a “bloody miracle.”

MAJ Frank Oxford Hayward, my father, was at Dunkirk. His unit, 13th/18th Royal Hussars, consisting of light tanks fought in the sustained rearguard action for the BEF. I have no precise details. Still trying to determine his exact role.

The recent film “Dunkirk” constitutes an excellent portrayal of the miraculous events affording the escape of some 344,000 troops. The military book “Dunkirk” authored by Joshua Levine, published by William Collins: 2017; is also an excellent read.

CAPT David L O Hayward (Retd)

Defense Analyst

Founder: China Research Team Australia (2003)

Whether his exact role was known or not he was a very brave man to be certain. He helped save many countries. Thank you.

To David L O Howard: Capt Howard: I am 87 YO, just a young boy during WW2, and have had very little interest in the details of the big war. I just wanted you to know that I got chills when I read your comment about your father and the fact that I was in touch with the son of a participant of this great event. Thanks.

I am resting in the hospital after surgery. I asked a student nurse what Dunkirk was. This Seattle student said she had no idea.

Bam!