By Mason B. Webb

In the summer of 1944, with American forces battling their way ever closer to the Japanese home islands, the need for ammunition in the Pacific was hitting its peak. Port facilities along the U.S. West Coast were running at full capacity, and few military facilities were busier than Port Chicago, a town of about 1,500 located 40 miles northeast of San Francisco, on the southern shore of Suisun Bay, near the city of Concord, California.

On July 17, 1944, two ammunition ships were being loaded with explosive cargo at Port Chicago’s twin docks: the 7,500-ton Liberty ship SS E.A. Bryan and the 10,000-ton SS Quinault Victory, the latter preparing to make her maiden voyage. The munitions had been manufactured at the Naval Ammunition Depot at Hawthorne, Nevada.

Everything seemed normal during the loading operations that day; 4,600 tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, depth charges, detonators, powder, and large- and small-caliber ammunition of all types were being inserted into the Bryan’s cargo holds, while another 429 tons were standing on the pier in 16 rail cars waiting to be loaded into the Quinault Victory.

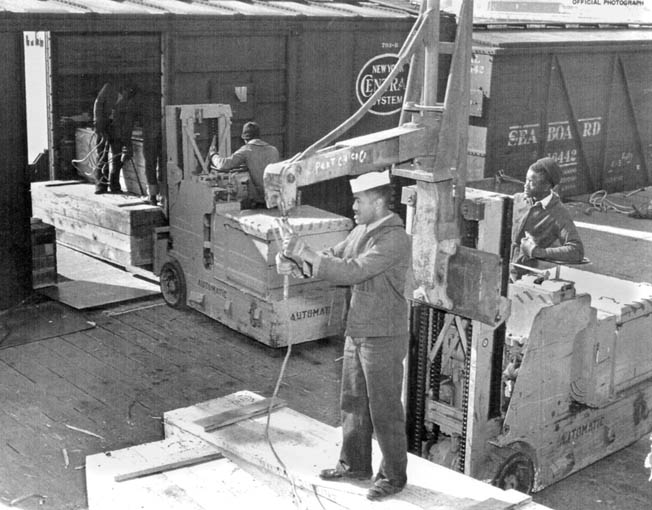

In the port area were 320 sailors, crewmen, and cargo handlers; all of the cargo handlers were African American, as the U.S. military was then racially segregated. The men and their white officers had been trained in general cargo handling but not in the specific craft of loading ammunition.

The officers frequently had contests to see whose crew of stevedores could work the fastest during their eight-hour shifts. Safety was not of paramount importance during these contests, and the officers often used threats of punishment to spur their men on.

After sundown on July 17, something happened at the port that, despite official inquiries, has never been fully explained. The Bryan had been loading for four days; 98 black enlisted men were on board, continuing to stack ammunition into the hold. Also on board were 31 Merchant Marine crewmen and 13 armed guards.

Moored next to the Bryan, the Quinault Victory also teemed with activity as loading was about to get under way; 100 black stevedores, 36 crewmen, and 17 armed guards were preparing for their shift.

Explosion at the Port

At 10:19 pm, a mighty blast erupted in the port area when one of the ships blew up, followed five seconds later by the other. The night sky was lit up by a gigantic fireball and structures close to the Bryan and Quinault Victory vanished in a blinding flash; the Quinault Victory, in fact, was raised into the air by the force of the double explosions and its bow catapulted 500 feet into the bay. The Bryan was virtually vaporized.

A naval aviator flying at 8,000 feet above the port at the moment of detonation had to quickly climb to 10,000 feet to avoid the fireball and debris hurtling up at him. A 200-pound fragment from one of the ships landed over two miles away. The seismic shock wave was felt 125 miles away.

Hundreds of civilians in the area were injured, including six at the Benicia Arsenal, located to the west across Suisun Bay, where $150,000 in damage was done to arsenal buildings. Buildings in the nearby towns of Martinez and Pittsburg suffered broken windows and cracked walls. At the Port Chicago Theater, a crowd of 195 patrons were watching a late-night war film when, at the moment a scene of a bombing came on the screen, the shock wave of the explosions hit the side of the building, caving in one wall; no one was seriously hurt.

But the devastation at the port was astounding. Buildings were leveled, vehicles and railroad cars were tossed about like toys, and fires were burning everywhere. Secondary explosions were also taking place. The town of Port Chicago was left without gas, electricity, or running water, and every building was either destroyed or damaged. Many survivors initially thought that the Japanese had just launched a sneak attack on the area.

A newspaper reporter noted, “Acres of pier had been blown away, leaving the tops of piles sticking out of the water.” An underwater crater measuring 66 feet deep, 300 feet wide, and 700 feet deep bore mute testimony to the force of the blasts.

The human toll was also great. Three civilian workers riding on a cargo-moving locomotive and 16 cars at the port “were never seen again, and pieces of the train were scattered over a wide area,” said one news report. Seventy Maritime Commission seamen died instantly, as did 15 Coast Guardsmen and nine Navy officers. Another 225 sailors—all African Americans working as stevedores at the port—also perished with barely a trace. The disaster accounted for almost 20 percent of all black naval casualties during all of World War II. Property damage, military and civilian, was estimated at more than $12 million.

The next day, about 200 of the black enlisted men volunteered to remain at the base and help with the cleanup operation. A search began to recover the bodies but there wasn’t much left to recover. One survivor recalled, “I was there the next morning. We went back to the dock. Man, it was awful; that was a sight. You’d see a shoe with a foot in it…. You’d see a head floating across the water—just the head—or an arm. Bodies—just awful.”

Of those killed, Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, commandant of the Twelfth Naval District, remarked, “Their sacrifices could not have been greater had [the disaster] occurred on a battleship or a beachhead…. Their conduct was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States naval service.”

Investigating the Disaster

An investigation was begun immediately into America’s worst home front disaster. A naval court of inquiry convened on July 21 to determine the cause, but Captain N.H. Goss, commanding officer of the naval ammunition depot at nearby Mare Island, stated, “We have no basis for giving any cause, as there are no close survivors to give evidence of what happened.”

The court of inquiry identified several possible causes of the first explosion, which touched off the second: “(1) Presence of a supersensitive element which was detonated while handling. (2) Rough handling by a person or individuals. This might have happened at any stage of the loading process from the breaking out of the cars to the final stowage in the holds. (3) Failure of handling gear, such as the falling of a boom, failure of a block or a hook, parting of a whip, etc. (4) Collision of the switch engine with an explosive-loaded car, possibly in unloading. (5) An accidental incident to the carrying away of the mooring lines of the Quinalt Victory or the bollards to which the Quinalt Victory was moored, resulting in damage to an explosive component. (6) The result of an act of sabotage. Although there is no proof to support sabotage as a possible cause, it cannot be eliminated as a possibility.”

Others expressed an opinion that the explosion could have been sparked by a careless match or discarded cigarette, but no definitive cause has ever been established.

A memorial service for the 322 victims was held on July 30, during which Navy planes scattered flowers on the water.

That might have been the end of the matter except for the fact that––less than a month after the disaster––a crew of black Navy stevedores refused their commanding officer’s orders to resume the handling of ammunition and the loading of cargo ships, this time at the Mare Island naval facility.

Racial tensions in the military had been simmering for quite some time, and many African American sailors objected to their being treated as second-class citizens while the United States was supposedly fighting a world war to free millions of people from Axis oppression.

Of the 328 African American sailors in the ordnance battalion at Mare Island–– many of whom had been at Port Chicago and had been buddies with those who died––some 250 refused to touch the ammunition. Of those 250, 200 of them faced summary courts-martial and were sentenced to bad-conduct discharges and the forfeiture of three month’s pay for disobeying orders. To make an example of them, the remaining 50, including one with a broken arm, were charged as being ringleaders of the refusal to obey an order and received a general courts-martial on the charge of mutiny, for which the maximum penalty is death.

All 50 were found guilty. Five men were sentenced to eight years in prison, 11 men got 10 years, and 12 received 24 years, in addition to dishonorable discharges. In January 1946, however, after a storm of public criticism, all the men were granted clemency but were required to remain in the Navy and were assigned to bases in the Pacific for a one-year “probationary period.”

Not long after the disaster, the ruined base was rebuilt, but the Navy eventually purchased the town of Port Chicago and demolished the remaining buildings. The ammunition depot there was later incorporated into the Concord Naval Weapons Station.

The Port Chicago Naval Magazine Nation Memorial

In 1999, President Bill Clinton pardoned former sailor Freddie Meeks, one of the few still-living members of the original 50.

The official Navy history notes, “The explosion and later mutiny proceedings would help illustrate the costs of racial discrimination and fuel public criticism. By 1945, as the Navy worked toward desegregation, some mixed units appeared. When President Harry Truman called for the armed forces to be desegregated in 1948, the Navy could honestly say that Port Chicago had been a “very important step in that process.”

Even that is not the end of the story, for much speculation after the war has postulated that a nuclear weapon was in the hold of one of the two ships and accidentally detonated; the Bryan was destined for the island of Tinian—the same island from which the B-29 Enola Gay would take off on its atomic bombing of Hiroshima more than a year later.

If this is true, the full story of Port Chicago may never be known.

Not much is left of Port Chicago. The town was purchased by the U.S. government in 1968 and all the buildings were torn down to create a safety and security zone around the Concord Naval Weapons Station. The site is located between Martinez and Pittsburg and north of Concord, and it can be difficult to gain access to the area as it is still a semi-active military base (Military Ocean Terminal––Concord); clearance to enter must be obtained from military authorities.

The Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial—one of only 29 areas around the country officially known as “national memorials”—is located near the waterfront. The names of those who died are listed on four memorial tablets. Remnants of the pier can still be seen in the water nearby.

Ed Bastien, a U.S. National Park Service ranger at Port Chicago and a Vietnam veteran, said, “I served in an integrated military, and I did so because of the actions of the men at Port Chicago.”

Bastien said he hoped that the National Park Service would eventually be allowed to build a visitors center here and spread the word about those who died at Port Chicago. “When I tell a vet that the round they chambered in their M-16 came through this very site,” he said, “their feet all of a sudden have a different feel on the soil.”

Guided tours are available at 1:30 pm Thursdays through Saturdays. Visitors are driven to the memorial by a shuttle provided by the National Park Service. Information, including details on how to register to visit the memorial, is available on the National Park Service Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial website or by calling 925-228-8860. Reservations must be made at least two weeks in advance.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments