By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Early in December 1941, Operation Typhoon, the German drive on Moscow, withered in the face of tenacious Soviet resistance and one of the worst Russian winters in living memory. The exhausted German Army was woefully unprepared for the bitter cold, which struck down man, beast, and machine alike. Soldiers froze to death or were crippled by frostbite while their draught horses perished by the thousands. Lubricants and fuel froze, firing pins snapped, tanks refused to start, machine guns fired no more, and aircraft were grounded.

At dawn on December 5 and 6, the fury of a Soviet counteroffensive sent the heretofore unbeaten Wehrmacht reeling back from the threshold of Moscow. At times in panic, at times in good order, the German Army was on the retreat. Behind their rear guard, nothing was to be left to the Red Army. Wilhelm Göbel of the 78th Infantry Division witnessed “the entire horizon glowing red from the fires of burning villages,” their hapless inhabitants left to freeze or starve to death. This was particularly tragic since the Russian peasants, who had no love for the Communists, had welcomed the Germans “liberators” into their homes.

Retreat is a Hard Pill to Swallow

For the troopers of the 2nd SS Motorized Division Das Reich, the order to fall back on December 9 was a hard pill to swallow. Only five days earlier, No. 1 Company of their Kradschützen (motorcycle) battalion had reached the end of the Moscow tramway system. Although dirty, unshaven, freezing, and plagued by lice, the SS troopers thought only of continuing the attack toward Moscow.

When the Soviet counteroffensive hit them, the Deutschland Regiment painted the snow brown with swaths of machine-gunned Soviet soldiers. Yet there was no escaping the inevitable. The division first fell back across the River Istra, then the River Rusa. By December 16, Das Reich found itself ordered to withdraw all the way back to Gshatzk, more than 60 miles west of Moscow!

The German front threatened to dissolve like Napoleon’s Grande Armée had over a century ago. As General Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, put it, “The German soldier does not go ‘Kaputt’!” Around the towns and villages of the principal railways and roads, the German “hedgehogs” fended off the oncoming Soviet formations like squares of pikemen had defied enemy cavalry in an earlier age. The panzer divisions acted like fire brigades to seal off Soviet breaches.

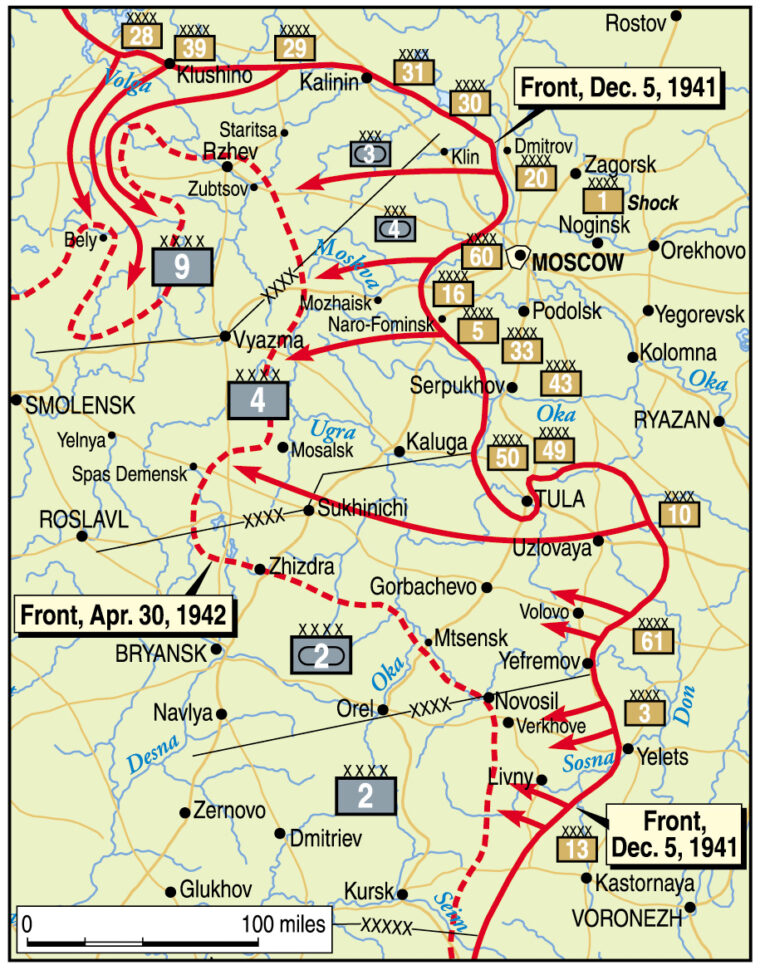

Nevertheless, for Army Group Center (AGC) the Soviet counteroffensive developed into a nightmare. Stalin tasted victory and craved more. Surely now was the time to crush the weakened Nazi invader in a “general winter offensive” along the entire front, from the Baltic to the Black Sea!

The main blow would come against AGC, where the Germans had not yet had time to recover from their setback at Moscow. Soviet Fronts (Army Groups) would slice open the northern and southern flanks of AGC. They would converge at Vyazma on the Motor Highway west of Moscow, the great supply artery of AGC. The bulk of AGC would be encircled, cut off, and annihilated.

The northern arm of the great Soviet pincer, General Ivan S. Konev’s Kalinin Front, bludgeoned its way through the German lines west of the Rzhev “hedgehog.” The move severed 23rd Corps from 6th Corps and the rest of 9th Army and threatened the Rzhev-Sychevka-Vyazma railway line. The Ninth Army was in shambles and faced destruction. To its rescue came its new commander, General of Panzer Troops Walther Model.

Model Takes Command

At Army headquarters, Model was asked, “What reserves have you brought us?” Model retorted, “Myself!” It was no mere bravado. The short and wiry general invigorated the demoralized troops with his own unshakable energy and optimism. Model spent about an hour each day poring over his maps and 10 hours visiting his troops. Paul Carell wrote, “Where he came, he worked like a battery that recharged the spent energies of the commanders.” At times, “pistol in hand,” he even led assaults against the enemy. Almost miraculously, he managed to close the gap between the 23rd and 6th Corps and secure the Rzhev-Sychevka-Vyazma railway line.

Closing the gap was one thing; holding it was another matter entirely. Nine Soviet rifle divisions and three to four cavalry divisions now lay isolated behind German lines. Ivan Maslennikov’s 39th Army and Vasilii I. Shvetov’s 29th Army would fight like trapped wolves to break free. Indeed, they continued to press toward their objective at Vyazma, still hoping to link up with the Soviet pincer battling its way north. To stop them, the 46th Panzer Corps, with the bulk of Das Reich and the 5th Panzer Division, the 1st Panzer Division, and the 86th Infantry Division, counterattacked to envelop the two Soviet armies in a gigantic “cauldron” west of Sychevka-Vyazma.

Meanwhile, west of Rzhev, Vasilii A. Khomenko’s 30th Army would use everything at its disposal to tear a fresh breach between the 9th Army’s 23rd and 6th Corps and reestablish contact with the 29th Army. Hitler insisted that an SS regiment bear the brunt of the Soviet relief attacks. There was really only one available, Das Reich’s “Der Führer” (DF), which at the time was not engaged. The regiment was placed under the command of the 256th Infantry Division, 6th Corps, and deployed at the very position where the Soviets previously breached the German lines. Here, foreboding 9-foot-wide tank tracks still marked two Soviet “snow roads” across the frozen Volga River.

Model Tells Kumm to Hold at All Costs

Model had utter confidence in the men of DF and their leader, OberSturmbannführer (Colonel) Otto Kumm. He had to. On them ultimately hinged the success or failure of the winter battle of Rzhev. However, from an original strength of around 3,000, DF’s ranks had depleted to only 650 men. They would rely greatly on their heavy and light infantry guns and 37mm Pak antitank guns. Would those be enough to stem the oncoming Red tide? “Hold at all costs … at all costs,” repeated a solemn Model to Kumm. “Jawohl, Herr General,” saluted Kumm.

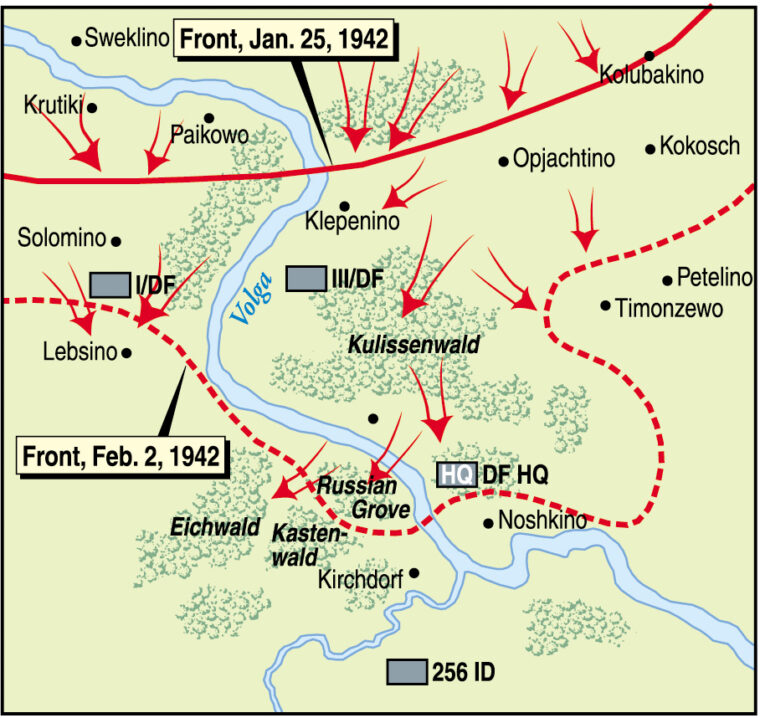

Der Führer’s four-mile front faced northward and through it, southeast to northwest, snaked the Volga River. The 1st Battalion of DF (I/DF) held the west side of the river, with its headquarters (HQ) at Lebsino. The III/DF held the front east of the river, its HQ at Klepenino. The remnants of DF’s 2nd Battalion had been disbanded earlier. The front line ran along the village strongpoints of Solomino-Klepenino-Opjachtino-Kokosch. The troopers used mines and cartridges to blast holes for machine guns and infantry dugouts at intervals of 100 to 200 yards.

To the south more villages and smaller woodlands ringed the large “Kulissenwald.” Regimental HQ was in Noshkino, south of the Kulissenwald. To the west, DF was flanked by units of the 206th Infantry Division, 23rd Corps, and to the east by the 161st Infantry Division and the 471 Infantry Regiment (IR), 6th Corps.

Probes by I/DF on January 26 found no enemy activity on its side of the river. Sturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) Erath mined the main roads through Pajkowo on the river’s southern bank. In the morning, elements of I/DF crossed the Volga and drove the Soviets out of Sweklino. In order to render it useless as an enemy base, the SS troopers leveled the village to the ground before withdrawing. Security positions were left at Pajkowo and its western neighbor, Krutiki.

On the eastern side of the river things did not go so well. The Soviets were well entrenched in a wooded hilltop to the north. German efforts to dislodge them were hurled back in a ferocious counterattack that claimed the life of the battalion commander, Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Schulz. German artillery and machine-gun fire stopped the pursuing Soviets cold.

Model made sure he stayed in constant personal touch with Kumm. When his vehicle was unable to break through the snow, he resorted to a Fieseler Storch aircraft and once even arrived on horseback. On January 27, Model was conferring with 23rd and 6th Corps’ commanders at DF’s headquarters when reports came in from I/DF: “The enemy is attacking this side of the Volga, from the northwest towards Solomino with strong forces, around 1,000 men.” This was the latest of several skirmishes along DF’s entire front line that had begun before midnight and lasted until the early hours of dawn. Up until 1030 hours, enemy forces, including the first armor sightings, congregated in strength in front of Klepenino. An icy wind swept over the Volga River as DF’s companies remained on constant alert, their weapons battle ready.

The German’s Prepare for the an Onslaught from the Soviet 30th Army

In heavy snowfall at 0200 hours on the 28th, the Soviets assailed Klepenino and Opjachtino and did not let up until dusk. So far the enemy had been repulsed everywhere. However, a captured Soviet radio operator confirmed that the entire 30th Army, seven rifle divisions and six tank brigades, stood ready to begin their attack the next morning. Contact was to be reestablished with the 29th Army to the south … no matter what the cost! Model, who happened to be there when the prisoner was brought in, took his leave of DF headquarters with the words, “Kumm, I’m depending on you!” and then added with a smile, “but maybe Ivan has swindled us.”

Model’s optimism proved unfounded. The next morning the Soviet 30th Army launched its attacks in earnest. Carell tells of how the Soviets hurled “battalion after battalion, regiment after regiment and finally brigade after brigade” at DF’s position but typically failed to commit their strength on a single focal point. The Soviets attacked for three long weeks, day and night.

Kumm described the nature of the fighting: “The heroism of the men in those days by far exceeds anything accomplished so far. Every attack is broken at the cost of fearful casualties, often in close combat with grenades and side arms. Mounds of enemy dead pile up in front of the company positions. Most horrible of all are the attacks by enemy tanks.”

Around Klepenino the enemy armor quickly became too much for the fatigued troopers of 9/DF (9th Company). On the 29th, troops from PzJgAbt 561 (tank hunter group) were sent in to support the defense. The Panzerjägers were only one of many units that would have to be rushed in to support the depleted ranks of DF.

Through snowstorms and temperatures that sank to 46 degrees below zero centigrade, the SS troopers held their lines against an equally determined enemy. Such cold froze a man’s breath! Possession of a village could make the difference between life and death. Overheated from combat, troops that spent the night in snow pits suffered from frostbitten toes and feet. In one instance, Soviets were so stiff and weak after a night outside that they were unable to hinder a German withdrawal even though the Germans passed within 100 yards!

Another feature of winter combat was that deep snow reduced the effectiveness of artillery. Snow dampened and reduced shrapnel spray and could nearly nullify mortar rounds and grenades. Mines could fail to detonate when driven over by vehicles.

All night long, there droned from above the sound of Soviet planes on their way to drop supplies to their beleaguered comrades in the cauldron. Although seven of their tanks were destroyed between Klepenino and Kokosch on the 30th, Soviet armor steamrolled over three machine-gun positions east of Klepenino. By 1800 hours, the Soviets entered the eastern part of the village. The soldiers of 9/DF, reduced to 30 men by 2200 hours, were hard pressed to expel the enemy.

From along the entire front, grim reports of company strengths reduced to 20 to 30 men trickled into DF HQ. Soviet units had penetrated as far as Timonzewo and infiltrated the Kulissenwald. To restore the situation, the I/471st Infantry Regiment with four Sturmgeschütze (assault guns) of Oberleutnant (1st Lt.) Wilhelm von Malachowski’s 2/StuGeschAbt 189 (the Ritter-Adler-Brigade) was placed under the command of DF. Malachowski had just been awarded the Knight’s Cross to which he was destined to add the Oak Leaves.

Das Reich had lost the last of its own Sturmgeschütze in the bitter fighting around the cauldron over the previous two days. Thirty-two unlucky officers and soldiers from the dissolved Sturmgeschütze battery were to be used as infantry for DF, while others were sent to Panzer courses in Vienna or transferred to Prague.

On January 31, at 1110 hours, the assault guns rolled into action through a flurry of snow. They supported the I/471st Infantry Regiment and two companies of the 256th Infantry Division as they counterattacked to secure the area between Klepenino and Opjachtino. Tank to tank duels developed in which three Soviet tanks were left burning. The remainder retired into the woods to the north. Whenever they dared reemerge from the thickets, the fire from the lurking Sturmgeschütze drove them back.

The 256th Infantry Division further stiffened Klepenino’s defense with the 3/256th Pioneer Company. Alongside 9/DF and the guns of Pz-JgAbt 561, the pioneers were able to fend off renewed Soviet penetrations north of the village. By February 3, the 13 50mm Pak guns of Leutnant (2nd Lt.) Peterman’s PzJgAbt 561 had tallied 20 T34s destroyed. At nearly 4,000 feet per second, the 50mm Pak’s AP40 shell could penetrate 56mm of armor sloped 30 degrees at a distance of 1,000 yards.

Burned out T34s had hopelessly blocked one of the gun’s views. Snowed in to its axles, its crew could not move the gun. Neither could any vehicle make it through the snow and tow the gun to a new position. A 30-ton T34 then flattened another Pak. More and more, the grenadiers and pioneers relied on mines and Molotov cocktails to disable the Soviet tanks.

Eastward from Klepenino, a renewed Soviet assault undid the gains of January 31 and broke through to the Kulissenwald. A hurricane of Soviet artillery fire played such havoc with German radio communications that the Soviet gains remained unreported at DF’s HQ. The resulting situation became so desperate that Das Reich fed 200 men of its own artillery regiment into the battle as infantry.

The German Defense at Optjachino Finally Cracks

On February 3, the German defense at Optjachino finally cracked. Thirty to 40 T34s closed in on the position of 10/DF. From 100 feet, three or four tanks systematically blazed away at each machine-gun nest and foxhole. After 30 minutes, the rending noise of metal tracks faded away as the steel juggernauts crept back into the woods. Deathly silence hovered over the battlefield. Hours later, a mortally wounded man staggered into III/DF’s HQ. It was Rottenführer (Corporal) Wagner, who collapsed and with his last words uttered, “Hauptsturmführer [Captain]! I am the last of the company! All the others are dead!”

A 1,000-yard hole now gaped in DF’s front line. Kumm pleaded for reinforcements from 6th Corps, but all that was immediately available was an ad hoc company of 120 drivers, cooks, and tailors led by paymasters. Having no other choice, Kumm reluctantly deployed the new “reinforcements” in the former positions of the 10th Company. Soon after, the Soviets attacked with grenades and their blood curdling “Urra! Urra!” cry. The nerves of the hastily raised German company immediately snapped, and they bolted to the rear. Soviet gunfire mowed them down in the open snow.

Despite heavy artillery barrages and renewed Soviet attacks, the German defenses at Klepenino continued to hold. East of the village, the Soviets swept toward the Kulissenwald in strength. German pioneer and construction troops, who strove to prepare a new defensive line, were surprised and blasted to bits. By the morning of February 4, Soviet units had crossed the woods and stood a mere 50 yards from DF Regimental HQ.

All remaining men, including adjutants, officers, radio operators, and drivers, toiled like devils to prepare the village’s eight buildings for defense. Pits were dug in the floors and firing slits cut into the lower beams of the walls. For three days the Soviets ceaselessly attacked, the gunfire of their tanks turning the houses to rubble. Hauptsturmführer Holzer was everywhere, inspiring the men to hold fast, and hold fast they did.

The Soviet attack temporarily blunted, the remaining two companies of I/IR 456 were thrown into the fray. One company struck northwest from Noshkino, along the road on the north bank of Volga that led to Klepenino. Before they reached the latter village, Soviets attacked from out of the woods and bogged down the company. A second company struck northeast for Timonzewo, but a Soviet company also intercepted them. Bullets whistled through the air, and many Germans were cut down, only their leader and 12 grenadiers managed to reach Timonzewo.

Subsequent German frontal and flank assaults on February 5 and 6 achieved little other than further thinning the German ranks. Soviet elements even crossed the Volga to take positions in a small wood and village, respectively nicknamed the Russian Grove and the Kirchdorf.

Mummert’s Arrival Drives the Soviets Out of Kirchdorf

Fortunately for the Germans, substantial reinforcements in the form of AA 256 (Reconnaissance Battalion) under the brilliant leadership of Major Mummert arrived at Noshkino. Mummert’s men drove the Soviets out of the Kirchdorf and around midnight made decisive headway in the Russian Grove.

February 6 was no less an eventful day for I/DF on the western side of the Volga. The advance units at Pajkowo and its neighboring village of Krutiki had long since been pulled back to strengthen the main defense at Solomino. After clearing mines and snow, the Soviets hit I/DF in full force. That day, all of 2/DF followed 10/DF to the grave. Aided by a hail of artillery fire, the remaining grenadiers of I/DF managed to hold on.

By the end of the 6th, DF was down to a total of 226 men and AA 256 down to just 150 men. PiBtl256 only had 68 men, while 52 men remained with PzJgAbt 561. There were less than 20 antitank and infantry guns left, only three of which were 50mm Paks. The remaining 37mm Paks were so useless against the thick, sloped armor of the T34s that the Germans nicknamed them “doorknockers.”

Facing DF were elements of the 363rd, 359th, 371st, and 375th Soviet Rifle Divisions and the 21st and 58th Tank Brigades. Between Klepenino and Timonzewo, a giant dent had been smashed into the DF’s front line, threatening to outflank Noshkino and drive a wedge between I/DF and III/DF.

The next day, from 0430 hours onward, hundreds of Soviet infantry supported by T34s stormed Solomino. Soon the last Pak in Solomino ceased to fire. The Soviets were temporarily thwarted by the timely arrival of the Sturmgeschütze of the Ritter-Adler-Brigade, which destroyed another five tanks. The Soviets, however, refused to give up and by 1400 hours had conquered the village. With barely a pause, they drove onward, forcing I/DF south toward Lebsino.

On the 8th and 9th, two Soviet battalions and four tanks hammered at Lebsino. The tanks ran two light howitzers and four 37mm Paks into the ground but lost three of their own in the process. For now, the Soviets were unable to make further headway.

At Lebsino, only 21 men remained in I/DF and 25 men in the 1st and 3rd Companies of the 251st Pioneer Battalion. There were also a handful of men from III/DF, who had been pulled out of Klepenino on the 7th. When only 14 men and 28 wounded remained to defend Klepenino’s southern ruins, Kumm had given the order to evacuate the village. Only a single house remained standing.

Destruction had not been wrought solely at Solomino-Lebsino and Klepenino; the entire front was enflamed by Soviet attacks. Artillery flashes lit up the night sky in apocalyptic fury. Kumm personally led many of the counterattacks in which a total of 24 enemy tanks were destroyed. His actions would earn him the Knight’s Cross.

The Deutschland Regiment Arrives in Support

More encouraging was the news that DF would receive 120 replacements. Better yet, their comrades from the HQ and first battalion of the Deutschland Regiment of Das Reich, a total of 590 elite troops, would be arriving forthwith from Rzhev. On the 9th, the troopers of Deutschland disembarked from a column of troop carriers. They took position to the right of DF with Battalion HQ at Petelino and Regimental HQ at Petuno.

The arrival of Deutschland marked the beginning of a more profound shuffle of divisional fronts. During the 10th and 11th, 9th Army transferred the remainder of Das Reich from the cauldron battle and from the command of 46th Panzer Corps. Das Reich was funneled into the critical sector of the 256th Infantry Division, from Petelino to Lebsino. The decimated Der Führer Regiment naturally left the command of the 256th and returned to its parent Das Reich Division. The 256th Infantry Division in turn took over the position of the 161st Infantry Division to the right. At the same time, Das Reich took over 10 formations already engaged in the sector, including 11 batteries of artillery.

Lebsino, meanwhile, continued to be one of the hotspots. On February 11, the II/IR 252 and PiBtl 251 were shoved out of Lebsino and from their positions to the east of the town. Fierce SS counterattacks by the remnants of I/DF managed to regain the town’s ruins, only to be again ejected by Soviet tanks. Kumm ordered another attack, and incredibly by 1345 hours Lebsino was again in German hands. Five more Soviet tanks were left smoldering. Late that night in snowfall, the Soviet attacks started anew.

Savage battles raged all along the front. At Timonzewo, Soviet thrusts continued to be blunted by the first battalion of the Deutschland Regiment, which had resolutely led the local defense for the last several days. More problematic were the events in the Noshkino-Kirchdorf-Russian Grove areas. New Soviet units, the 24th Ski Brigade and the 174th Rifle Division, were reported. By nightfall, in the midst of continuing blizzards, elements of the 371st and 171st Soviet Rifle Divisions supported by 40 tanks breached the defenses of the completely spent AA 256 at Noshkino.

The Battle for the Russian Grove

The Soviets also reentered the Russian Grove, and to clear them out Das Reich called upon its Kradschützen Battalion. On February 12, Hauptsturmfuhrer Tychsen, accompanied only by a signaler, was reconnoitering the ground ahead when he was seriously wounded in the chin by a grenade splinter. It was an evil omen for the next day’s disastrous attacks. The SS failed to clear the thickets of Soviets and suffered 85 dead, including Untersturmfuhrer (2nd Lt.) Müller.

Obertsturmführer (1st Lt.) Buch of the SS KradschBtl left an account of the battle:

“Everything depended on the heavy weapons because the front was only thinly held. We sat in snow bunkers and during the day lay in heavy artillery fire.

“A pause in the artillery bombardment meant that the Russian attack was coming. Mostly one Russian company, never a battalion, pushed from the steep Volga bank through the Russian Grove and attempted to overrun the 4th Company….”

A hailstorm of machine-gun, machine pistol, and hand grenade fire forced the enemy to take cover. Now was the time for the SS artillery to speak. Infantry guns and mortars pounded the Russians.

“Their attack having being shattered the Russian artillery opened anew and the ‘game’ began again,” the soldier continued. “Fortunately we had enough ammunition. The Infantry guns and the heavy mortars shot 600 rounds a day. The artillery fire could not be placed close enough because the worn out barrels of some guns scattered their bombardment over 300 yards.

“Simultaneously our attention was diverted to the north where the section of our neighbor was inflamed by renewed T34 attacks. The Stugs of Stu.Gesch.Abt. 189 under Oblt. v. Malachowski drove by us every time there was trouble to the north. In the beginning there were still five Stugs, then there were less and less. They were glorious boys, those Stug gunners. On their returns they shouted out the tally of enemy tanks destroyed, ‘six T34s’ or ‘this time only three T34s!’”

Das Reich historian and veteran Otto Weidinger’s account of the fighting in the sector relates, “In the Russian Grove the enemy is so well entrenched that it proves impossible to dislodge him. But the fire of a 21-cm mortar lobs a grenade into the wood every 4-7 minutes and keeps the enemy suppressed. During these days, the Kirchdorf, a small rise with its church and few buildings, changes possession ten times, but in the end remains in the hands of AA 256.”

On February 14, 20 Soviet IL2 bombers pounded the entire front, from Petelino to Lebsino. The Sturmgeschütze of Abt 189 again proved their worth by nullifying a T34 breakthrough at Lebsino. The next day, however, eight T34s and two rifle battalions ground their way into the village and threatened to push farther to the south. After the Sturmgeschütze destroyed seven more Soviet tanks, the situation was somewhat relieved, but subsequent exertions failed to regain the village. The bodies of German troopers lay strewn among the burned-out Soviet tanks. Equally alarming was the loss of two Sturmgeschütze, one 50mm Pak, and the only 88mm flak gun used in the counterattack.

Cauldron Battle in South Reaches its Fateful Climax

The Soviets achieved more success to the southeast, making gains in Noshkino and the Kirchdorf areas, and pushing farther west, to the Kastenwald and Eichwald. Their efforts were building to a feverish pitch because the cauldron battle to the south was reaching its fateful climax. It was now or never if the trapped divisions were to be saved. Model, likewise, intensified the 9th Army’s efforts to bring the battle to a close.

At dawn on February 16, Stuka dive-bombers screamed down on the Soviet positions in Lebsino. Unfortunately for the Germans, the two remaining Sturmgeschütze that were to support the follow-up attack on Lebsino were stuck in the snow and could not be shoveled free until the early afternoon. With their narrow tracks and limited clearance, the German armored vehicles were poorly designed for winter combat. The Germans themselves, on the other hand, dubbed their chief enemy, the T34, the “Snow King.” The attack was subsequently cancelled.

The next day, those same Sturmgeschütze were back in action, supporting the hard-pressed SS Kradschützen resisting the Soviets in the Kirchdorf area. Four more Soviet tanks were knocked out, but then the overstressed Sturmgeschütze broke down due to mechanical problems. Still, the Soviets proved unable to breach the paper-thin Kradschützen line. As usual, the SS paid a heavy price. Hauptsturmfuhrer Grünwalder joined many of his troopers in death, and the battalion was reduced to 70 men.

Hours later, after some quick repairs, the Sturmgeschütze rumbled north to rejoin the delayed counterattack on Lebsino. Stuka bombardment plowed up the Soviet defenses, and by 1710 hours Lebsino was back in German hands, but not for long! Another Soviet counterattack with seven tanks and 200 men drove the 60 Germans out of the village, which by now had become a mass grave for many German and Soviet soldiers.

Finally, in a last-minute exertion to save their doomed comrades, six Soviet tanks burst through Das Reich’s lines. The SS Grenadiers took care of the Soviet infantry that followed in the tanks’ wake, but nothing was able to stop the tanks themselves. They kept going all the way into the back of the 1st Panzer Division, which was busy eliminating the cauldron. The brave efforts of the Soviet tank men were in vain. Model himself took the matter in hand and destroyed five of the tanks with a deadly artillery barrage.

Late in the afternoon of February 17, Kumm received a heartening message from Matthias Kleinheisterkamp, the Das Reich Division commander. “The enemy in the Sychevka cauldron is destroyed. Der Führer will be taken out of the front line the following day.” Orders followed for the 251st Infantry Division to take over Das Reich’s entire section. Das Reich’s formations gathered west of Rzhev and went into Army reserve.

The Soviets Took a Beating

After the 17th, almost like magic, Soviet attacks on Das Reich’s sector trickled to a halt. Sporadic fighting continued nevertheless, as the tenacious Soviets refused to relinquish any of their hard-fought gains. However, it was clear that the battle had run its course. The Soviet 30th Army gave its all against long odds as the soldiers of Das Reich and the Wehrmacht persevered.

It was time for both sides to lick their wounds, and those wounds were deep. Caught in the cauldron, the Soviet 29th Army was virtually obliterated. The mangled Soviet 39th Army and the 11th Cavalry Corps barely escaped the same fate and were trying to escape southwest under cover of woods and darkness. Six Soviet divisions were shattered, four nearly so, and nine others plus five tank brigades badly mauled. On the Soviet side, 27,000 had died, and 5,000 marched into captivity. A total of 187 Soviet tanks, 343 infantry guns, 256 antitank guns, and seven antiaircraft guns were destroyed or captured. To this was added the tally of the 8th Fliegerkorps (Air Corps), which accounted for 68 enemy aircraft, four tanks, 28 guns, and over 300 trucks.

The beating taken by the Soviet 30th Army in its relief efforts was only a little less severe, as Otto Kumm relates in his book Kameraden bis zum Ende (Comrades till the End): “During these weeks, the enemy has lost 15,000 dead in front of the regiment’s section. Through the exact knowledge of the Soviet regimental numbers and repeated questionings of prisoners, it was possible to determine the casualties of the Russian battalions and regiments. At the same time seventy enemy tanks were shot down in the regiment’s section, not counting tanks that broke through and were destroyed by other German elements.”

A Valiant German Defensive Stand

Kumm praised the many battalions that were placed under DF’s command, especially the “splendid cooperation” from the 5/AR 256 Battery, the Sturmgeschütze of Malachowski’s Ritter-Adler-Brigade, and the AA 256, whose Major Mummert was awarded the Knight’s Cross on Kumm’s recommendation. On November 4, 1942, the Knight’s Cross was also awarded to Das Reich divisional commander Matthias Kleinheisterkamp.

Biehler, the commander of 6th Corps, wrote in his war diary, “The heroic deeds of every soldier, who fought in the hells of Klepenino, Solomino, Lebsino, Noshkino, Kirchdorf and Timonzewo, are above praise and forever will go into the history of the German Ostheer.”

Model was visiting the Das Reich divisional headquarters when Otto Kumm personally reported in. Model addressed Kumm, “I know what your regiment went through, Kumm. But I still can’t do without it. How strong is it now? Kumm pointed to the window: “Sir Colonel General, my regiment is on parade outside.” Model looked outside. There stood 35 men! At Rzhev, the soldiers of Das Reich paid homage to the SS accolade “Your honor is loyalty” with their deaths.

As heavy as the German sacrifices were, Model had reversed two months of defeats, saved the 9th Army, and in conjunction with the German successes south of Vyzma, saved Army Group Center. In the latter area, however, it was not until the spring that the penetrating Soviet armies were smashed in the great battle of the Ugra bend.

Model paid respect to his soldiers in the 9th Army with the following message: “Every leader and soldier of the army takes credit for our victory.… Like an unbreakable shield our defense held out in the east and north so that the sword of our counterattack could strike to destroy the enemy….

“Today the Führer has bestowed upon me the Oak leaves to my Knight’s Cross. I will carry it in thankful pride of you, soldiers of the Ninth Army—especially of those who gave their lives to fulfill our mission.”

The bloody reversal of the Soviet winter offensive against AGC was mirrored by unachieved objectives to the north and south. General Georgi Zhukov commented on the Vyazma battles, “We overrated our own driving force, and underestimated that of the enemy, who proved a much harder nut to crack than we had supposed.” Zhukov had wisely counseled from the start that the Red Army did not have the resources to achieve victory everywhere, but an overeager Stalin had not listened to him.

Nevertheless, the great German defensive victories could not disguise the fact that the Wehrmacht had failed to capture Moscow. The war would go on. For the troopers of 2nd SS Division Das Reich, their comrades in the Wehrmacht, and their Soviet foes, there would be no rest. Inexhorably, total defeat would come.

Ludwig Dyck has written on numerous occasions for Sovereign Media publications. He has done extensive research on World War II on the Eastern Front and resides in Richmond, British Columbia, Canada.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments