By Frank R. Shirer

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is a work of fiction written as if it were historical fact. It is a chapter in a book of alternate history entitled Rising Sun Victorious (Greenhill Books, London, 2001), which is a compilation of like chapters and was a Main Choice of the Military Book Club and Alternate Selection of the History Book Club. It posits alternative effects during and after the Pearl Harbor attack, assuming certain small alterations in the hours just preceding. We present it because we believe important events unfold owing to small as well as large natural and human actions, and that it is well to remember this. We hope you accept it in this spirit and that it stimulates your thinking about the battle. Except for the arrival time of the USS Enterprise which here is posited as 8 am on the 7th, rather than the historically accurate 8 pm, all is historically correct until the subhead “Stark Alerts Kimmel.”

December 7, 1941, is a day that has lived in infamy—not only because of the surprise attack of the Japanese on Oahu, but because America’s sentinels were asleep at their posts in Hawaii. The well-planned attack was successful because the Americans feared sabotage by a “fifth column” more than an aerial attack, an attack that the U.S. Navy had proved altogether possible in 1933. The thought pervading the command structure in Hawaii was that if Japan did move against the United States, the attack would come in the Philippines, to guard the left flank of its march on the oil fields in the Dutch East Indies.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had been charged with leading the Japanese Navy’s assault to seize the natural resources Japan required. He realized that to buy time to consolidate Japanese gains in the Indies, he would have to remove the U.S. Pacific Fleet as a threat. Commander Minoru Genda devised the plan that he used. It called for a fleet of six aircraft carriers, escorted by fast battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and tankers, to sail north of the regular shipping lanes through the North Pacific to a point 200 miles northwest of Oahu. From there nearly 400 torpedo, dive, and level bombers and Zero fighters were to be launched in two waves against the American fleet on a quiet Sunday morning. The final approved order left open the possibility that there might also be follow-up strikes.

The First Air Fleet, composed of the First (Akagi and Kaga), Second (Soryu and Hiryu), and Fourth (Ryujo) Carrier Divisions, was to be the centerpiece of the attack force. The Ryujo was detached during the summer of 1941 because she had older Type 96 Claude fighters, and the Fifth Carrier Division (Shokaku and Zuikaku) was added. Selected to command this powerful carrier force was Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who was unacquainted with naval aviation, but who specialized in torpedo attacks and large-scale surface warfare. He got the job because of his seniority.

Nagumo expressed his misgivings about the attack and enumerated the risks. It would be difficult, he said, to keep an exact timetable across over 3,000 miles of ocean, to refuel the escorting destroyers in the rough winter North Pacific waters, and there was an ever-present chance of discovery by American submarines, aircraft carriers, or land-based aircraft. Nagumo also stressed the outcome of an August war game in which the attack force had two carriers sunk and two damaged, and lost 40 percent of its aircraft and aircrew. However, he said that he would follow orders and command the First Air Fleet.

For 10 days the fleet sailed across the North Pacific, arriving undetected at its final refueling point 600 miles north of Lanai Island at 5:30 am on December 6. After refueling of the carriers, cruisers, and destroyers was completed the tankers departed for their December 13 rendezvous point west of Midway Island. Three hours later, Vice-Admiral Nagumo broke out the famous “Z” flag which Admiral Togo had used at Tsushima, and ordered the fleet to begin its final high-speed (24-knot) run to the launching point, 240 miles north of Pearl Harbor, at 6:00 the next morning.

Still nervous about being discovered, Nagumo kept all of his scouting planes out of the air that last day. None would be launched until the following morning, when they would do a final reconnaissance to determine whether the U.S. fleet was at Lahaina Roads or in Pearl Harbor, and whether or not the American carriers Lexington and Enterprise were in port.

Pearl: A Quiet Saturday

Saturday, December 6, saw American Army and Navy units in Hawaii securing their equipment after a week of training. The battleships were preparing for an “Admiral’s inspection” that would commence on Monday. They had spent the day opening up entry hatches into the double bottoms and dogging open watertight doors, which were usually closed even in port and always at night. The 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions and the Coastal Artillery Command, which controlled army anti-aircraft batteries in the area, were cleaning up their equipment and returning ammunition to bunkers for proper storage. It had been a week of Alert Number Three (full alert) for the Army troops, even though few among the local populace had noticed.

That evening soldiers and sailors, officers and men, went on liberty, to Pearl City and Honolulu, to enjoy an evening off before a lazy Sunday. There were still three task forces at sea. Enterprise (Task Force 8, or TF8) was returning from delivering a Marine F4F-2 (Wildcat) squadron to Wake Island; after encountering heavy seas on the 5th, she got clear weather on the 6th and expected to dock at Pearl by 8:00 Sunday morning. Lexington (Task Force 12) was en route to Midway Island to deliver a Marine dive-bomber squadron. And Task Force 3, consisting of the cruiser Indianapolis and five destroyers, was on patrol near Johnston Island.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco 16 B-17 Flying Fortresses (eight C and eight E models with partial crews, no ammunition, and their machine guns still packed in cosmoline) had already taken off for a night flight to Hawaii. There they would refuel, get some crew rest, and then continue on to reinforce the Philippines. They were scheduled to arrive on Sunday morning at 8:30 am Hawaii time.

In Washington, D.C., the Army and Navy departments were receiving a 14-part message that Tokyo was sending to its embassy. It was to be distributed to the President, Secretaries of War and Navy, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold R. “Betty” Stark, and Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall. It would not be until the following morning that decisions would be made that alerted the commanders in Hawaii, giving them just a couple hours’ explicit warning that they might be attacked in force by the Japanese.

December 7, Last-Minute Alert

Just after midnight, December 7, the 14th part of the message arrived in Washington, where it was decoded, then left until morning for translation and delivery. Lt. Cmdr. Alwin D. Kramer (Office of Naval Intelligence) and Army Col. Rufus S. Bratton (Army G-2), who shared the duties of distributing decoded messages from Japan, arrived at their office in the Navy Department by 9:00 am EST (3:30 am at Pearl Harbor (PH)). They translated the 14th part and prepared copies for delivery. Admiral Stark was in his office already that morning, while General Marshall was out for his morning ride at Fort Myer, Virginia.

While the two Intelligence officers were making their rounds with messages, the minesweeper Condor reported spotting a submarine in the Defensive Sea Area around Oahu. It notified a nearby destroyer, U.S.S. Ward, at 3:42 am (9:12 EST). Ward searched fruitlessly until 4:35, when she returned to her regular patrol route outside the harbor entrance. She did not detect the five I-class submarines that were lying in wait in a double arc outside the channel. They had already surfaced and launched their two-man mini-submarines, which would penetrate the harbor and assist in the coming attack.

Stark Alerts Kimmel

Lieutenant Commander Kramer walked down the corridor of the Navy building to the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) office. One of the instructions in the 14-part message to the Japanese Ambassador was to deliver it to the U.S. government at precisely 1 pm Washington, D.C., time. Kramer gave the message to Commander Arthur H. McCollum, chief of the Office of Naval Intelligence’s (ONI) Far Eastern Section, shortly after 10:00 EST, pointing out that 1:00 pm EST was 7:30 am in Hawaii and 2:00 am in the Philippines. He then continued with his deliveries to the White House and the State Department. McCollum took the messages to Admiral Stark and ONI Chief Captain Theodore S. Wilkinson. During the next few minutes the messages were read and re-read.

Finally, Captain Wilkinson said: “There is enough here to indicate that we can expect war.” Admiral Stark agreed. Then Wilkinson suggested: “Why don’t you call Kimmel?”

Stark paused, then picked up his scrambler telephone. His call reached Admiral [Husband E.] Kimmel at 5:15 am (10:45 EST), awakening him. Stark briefly told Kimmel about the 14-part message that seemed to break diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Japan. He also informed him that the message ordered the [Japanese] Embassy [in Washington, D.C.] to destroy all its codes and coding machines. Kimmel asked about the portent for Hawaii. Stark responded that he did not know, but that he feared that an attack might occur because the Japanese consulate in Honolulu had also been ordered to destroy all its codes and papers. Kimmel mentioned that Captain Layton had told him on Saturday that the consulate personnel were burning a lot of papers. When asked about the status of the fleet, Kimmel said that it was safely in harbor and preparing for his inspection the following morning.

At that, Stark blew up in rage. “Didn’t you get our message of 27 November stating that ‘this is a war warning, execute defense deployment’?”

“Yes,” replied Kimmel, “but I figured that you were talking about strategic defensive deployment, when I deploy the fleet to sea after the beginning of hostilities.”

“NO!” exclaimed Stark. “I expected you to begin wartime defense measures, including defense against attack, while the fleet is in the harbor. Don’t you remember Admiral Schofield’s 1933 war games? I thought you were there.”

“No, I wasn’t out here then,” said Kimmel. “I remember something about it. Didn’t he strike Pearl with the carriers?”

“Yes, carriers striking from the north. Your first concern is to protect the fleet and that includes when it is in the harbor.”

“I’ve got the fleet at stage three,” said Kimmel, “but I’m doing an inspection tomorrow. Most of the battleships are open for that. I’ve let Bloch and Short take care of the harbor defense.”

“You had better go to condition Zed on all your ships at once and recall all your people just in case,” advised Stark. “Captain McCollum says that he thinks that the Japs will attack our fleet out there because it is a threat to them, even if they go for the Philippines.”

“I’ll call Bloch and my chief of staff as soon as we finish and get the fleet to General Quarters,” replied Kimmel. “It will take us two or three hours to get fully ready, and four hours to get up enough steam to take the fleet to sea. Hopefully we can get some PBYs up. I remember Ellis Zacharias telling me last May that he though the Japs would attack here with carriers and from the northwest. I’ll have them search in that direction.”

“You may not have that long,” said Stark. “But hopefully this will end up being a drill that will just cause the folks to grumble about having their weekend loused up.”

“Yes, Sir,” said Kimmel. “Let me get off and call my people.”

“Good luck.”

Kimmel called the commander of the 14th Naval District, Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, and ordered him to put the District on alert and to notify the commander of Patrol Wing Two, Rear Admiral Patrick N.L. Bellinger, to get PBYs (flying boats) into the air as quickly as possible. They were to search to the north, 60° either side of 0° north out to a distance of 700 miles. He closed by telling Bloch to meet him at his headquarters by 6:00.

Bellinger’s Patrol Wing 2 was at Condition B-5, which meant that 50 percent of the PBY-3s and -5s and their crews were on four hours’ notice. In reality they had less than two hours to avoid being caught on the ground at Ford Island and Kaneohe Bay Air Station. Kimmel rapidly dressed and was driven to his headquarters in the Submarine building. He had already forgotten about his 8:00 golf outing with Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, and about contacting him to cancel it.

As all of this activity was taking place in Hawaii, the Japanese were launching their aerial armada’s first wave of 183 bombers and Zero fighters.

As the American fleet was being awakened and the battleship crews were rapidly closing up the inspection hatches and undoing the preparations for Admiral Kimmel’s canceled inspection, the tug Antares sighted a submarine off the harbor entrance. She signaled U.S.S. Ward, which was still on patrol. Steaming to the Antares’ assistance, Ward engaged the unidentified submarine with gunfire and depth charges and sank it in five minutes. At 6:51 Lieutenant [William] Outerbridge, Ward’s captain, reported: “Depth-bombed sub operating in defensive sea area.” The 14th Naval District immediately relayed the message to Admirals Bloch and Kimmel.

At 6:45 the first of U.S.S. Enterprise’s air complement of SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bombers and TBD Devastator torpedo-bombers began landing on Ford Island. Their arrival was the first notification for Admiral Kimmel that Enterprise was nearing the harbor after being delayed by a day due to heavy seas. Kimmel had ordered her to sail under radio silence and thus did not know her exact arrival date. He immediately notified her commander, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., to keep his task force (TF8) south of Oahu, and go to General Quarters. He also told Halsey that his planes would be fueled, armed, and returned to him. Throughout it all, he added, Halsey’s force was to maintain radio silence.

The Hawaiian Air Force

While Admiral Kimmel was putting the fleet on general alert, Lieutenant General Short continued to sleep, as did Major General Frederick L. Martin, commander of the Hawaiian Air Force. At 6:45 Rear Admiral Bellinger awakened Martin by phone to tell him about the warning from Washington and that he was launching his PBYs to scout the northern approaches to the islands. He wanted to know if Army radar sites on the northern side of the island at Opana Point and Kaaawa were working that morning and if the Air Warning Center (AWC) was manned. Martin said that the three sites were scheduled to operate until 7:00 but that there was only a skeleton shift on at the AWC. Bellinger said that he was sending the Navy’s AWC liaison officer along with the Navy contingent responsible for coordinating with all Naval aviation units.

Earlier that year, Martin had worked with Bellinger to split the responsibilities for reconnaissance and aerial defense of the islands. The Navy would do the bulk of the reconnaissance, while the Army would provide air defense. Martin’s B-17 force had been reduced from 35 in May to only a dozen when 23 were sent to the Far East Air Force in the Philippines in September. Six of the remaining 12 were nonoperational hangar queens, providing replacement parts for other B-17s shuttling from the United States to the Philippines. Martin also had 33 obsolete B-18s (only 21 of them flyable) that could perform reconnaissance. These 45 aircraft were a far cry from the 180 B-17 or equivalent aircraft that an official study completed earlier in the year had said would be necessary to provide 360° coverage for the islands against a possible attack by six enemy aircraft carriers.

The 14th Pursuit Wing had four interceptor and four fighter squadrons, all stationed at Wheeler Army Air Field. The Army fighter force had 99 modern P-40 Bs and Cs, and 39 P-36As, although only 64 P-40s and 20 P-36s were operational that Sunday morning. Martin had two P-40 squadrons (12 aircraft each) temporarily posted to the outlying Bellows Airfield (44th Pursuit Squadron [Interceptor]) and Haleiwa Airfield (47th Pursuit Squadron [Fighter]) for gunnery training. Major General Martin had been preparing for possible hostilities by having 120 revetments constructed at Wheeler Field for the pursuit aircraft.

Lieutenant General Short’s Alert Number One was designed to protect against sabotage rather than an air attack. It ordered Martin to group all of his fighters close together and in the open so that they could be easily guarded against sabotage with the minimum of personnel, instead of leaving them in their revetments, which required a larger guard force. Additional security measures included: the locking of the controls in each plane via a system of cables and locks, which normally required three to four minutes to undo; and the storage of all machine gun ammunition in hangar number three, with individual .30- and .50-caliber rounds stored separately from their belts.

The Hawaiian Air Force was also on a four-hour alert status for half of operational aircraft to get airborne. They would need every minute of it considering the need to recall pilots, belt the ammunition, and get to altitude in the sectors where enemy aircraft could be expected. The planes at Bellows were in particularly bad shape. After a week of gunnery training, they had not only been parked on Saturday afternoon without having their fuel tanks filled, but their machine guns had been removed so that the armorers could give them a thorough cleaning on Sunday. The 47th Squadron had its P-4OBs’ fuel tanks full and machine guns on board, but in their ammo dump they had only .30-caliber ammunition for the wing guns and no .50-caliber ammunition for the twin-fifties in the fuselage.

Late Word to the Army

Back in Washington, General Marshall arrived at his War Department office at 11:30 EST (6:00 PH) and found Colonel Bratton waiting for him with the 14-part message. After reading it he wrote a warning message to be radioed immediately to all Pacific commands. All were notified except for the Army commander in Hawaii, Lieutenant General Short, because the radio circuits were down. Bratton decided not to send via RCA (Radio Corporation of America) and urged Marshall to telephone Short with the warning. Marshall hesitated, noting that the Army suspected the Japanese had tapped the transoceanic cable and could decode scrambled telephone conversations. Bratton said that he thought the chance had to be taken, and reminded Marshall that he could use the 1:00 pm meeting between Secretary Hull and Ambassadors Nomura and Kurusu as the reason for the call, to check on their alert status. At 6:50 (12:20 EST) Marshall telephoned Short, awakening him.

General Marshall inquired what alert status the Hawaiian Army was on. Short replied, “Alert Number One.” Marshall was relieved, because Alert One meant all troops were on full alert, with antiaircraft artillery in defensive positions and the air force on 30-minute take-off status.

“I’m glad you’re on full alert,” said Marshall, “that’s what’s needed. I don’t see sabotage as the major threat this morning.”

Short replied: “Alert One is antisabotage. I changed the numbering last summer after I arrived, so folks out here wouldn’t be alarmed.”

Shocked at this revelation, Marshall was furious. “You know the Army standard is for Alert One to be full alert. Did you pass that change on to War Plans here? If you had, I would have denied permission for it! You need to get your folks up and deployed right now! It may be nothing, but I don’t think this is the time for worrying if the local civilians are ‘alarmed’.”

Short was startled. “We just came off of a week’s full alert yesterday morning, but OK. I’ll call everyone out now.”

“Let’s hope that nothing happens,” replied Marshall, “because that is what you bet your stars on when you changed the alert procedure. I didn’t expect you to be asleep on guard duty out there.”

As Short hung up his phone rang again. This time it was Major General Martin calling to inform him of Rear Admiral Bellinger’s call and of the Navy’s full alert status. Short told Martin to put the Hawaiian Air Force on full alert as well. The island defense plan was to go into effect. PBY patrols were to be reinforced, and fighters were to be manned and ready. Short called Colonel Walter C. Phillips, his Chief of Staff, and repeated the instructions to him. The time was now 7:15.

The First Wave Strikes

The Opana Point radar site was slated to close down at 7:00. Since the morning chow truck had not arrived, however, its operators, Privates Joseph L. Lockard and George E. Elliot, decided to keep the set on and to get more training. At 7:02 a large blip appeared on the radar screen. They estimated it included at least 50 aircraft on a heading of 3° east of north at a range of 130 miles. They continued to track the southward moving target for 13 minutes before they called the AWC to report that the target was now 80 miles from Opana Point on an inbound bearing. Only a single telephone operator and the duty officer, First Lt. Kermit A. Tyler, were in the AWC when the report came in. Tyler concluded that the sighting involved Major Landon’s flight of 16 B-17s, due in that morning from San Francisco.

The Japanese cruiser Tone’s floatplane spotted Enterprise and the rest of TF8 at 7:33 and reported it to Commander Fuchida. Two minutes later, Chikuma’s Pete reported that there were no aircraft carriers in Pearl Harbor but that there were many carrier planes landing and taking off from Ford Island and that ships seemed to be getting up steam. Commander Fuchida faced a decision about how to exploit this new and unexpected information. He quickly decided to split his attack force between Pearl Harbor and TF8. He ordered the torpedo-bomber and fighter squadrons from Akagi and Soryu (20 Kates and 18 Zeros), along with two of Zuikaku’s dive-bomber squadrons (18 Vals), to find and sink Enterprise along with her escorting cruisers. The remainder of the force would attack Pearl Harbor as planned. At 7:45 he fired double red dragon flares to signal “surprise lost” to the half of the force that was to attack Pearl.

Simultaneous with the Japanese scout plane reports came the arrival of Commander William E.G. Taylor and the Navy’s four-man contingent at the AWC. Tyler received a call from Maj. Kenneth P. Bergquist, the AWC’s second-in-command, asking if any radar sites were still operating and if any recent targets had been reported. Tyler told him of Opana Point’s report. Bergquist ordered him to call Opana Point to see if they were still tracking it. While Tyler was making his call, Major Bergquist phoned Major General Martin about the blip. Martin said that it could not be the B-17s because it was coming in from the wrong direction. Martin then called Wheeler Field and told them to get every P-40 and P-36 they had airborne and to intercept a possible enemy force to the north of Oahu. Bergquist had Army plotters recalled from breakfast to put the AWC into full operation. He also ordered the crews of the sites at Kaaawa on the northeast coast and at Koko Head to resume operation.

The resources and expertise of Commander Taylor and Major Bergquist had been squandered because of interservice noncooperation, a lack of understanding of radar by Lieutenant General Short and Admiral Kimmel, and the lack of central Army control over the Air Warning System and its radar. The final Opana Point radar plot came in at 7:39, when Lockard and Elliot reported contact being lost as the target entered a “dead space” 20 miles to the north. It was just after disappearing from the radar screen that Fuchida split his force.

By then the crews at the various American airfields were scrambling to disperse and ready their fighters, bombers, and PBYs for combat. Dragged from their all-night poker game, Second Lts. Kenneth M. Taylor and George S. Welch were among the pilots sent from the Wheeler Field BOQ (Bachelor Officer Quarters) to their planes at Haleiwa and Bellows Fields. The Japanese were unaware of Haleiwa Field and had not targeted Bellows in the first wave. The splitting of the strike force had halved the fighters and had reduced to nine the dive-bombers allocated to strike Wheeler Field.

Nine Val dive-bombers and six Zero fighters began their strike on Wheeler Field at 7:52. The Vals struck the fuel dump and then each of the hangars in succession, just as they had practiced. The Zeros began their strafing run from the west end of the field. However, they found not a neat row of planes as expected but only a dozen P-40s and P-36s along with another 14 obsolete P-26s sitting out in the open. The majority of the P-40 Tomahawks were in their revetments, protected from the first strafing attack, but six were taking off as the attack began, in response to Martin’s order to intercept the unidentified target north of the island. Two of these were shot down as they were pulling their wheels off the runway. The leading four climbed for altitude as the Zeros went in the opposite direction. Within moments the Zeros zoomed to engage the Tomahawks, leaving the strafing to the Vals, which were ill equipped for the mission. In the swirling dogfight that followed all of the P-40s were shot down, but they claimed one Zero. The Army pilots had been caught at take-off and knew little of how the Japanese flew and fought. Their sacrifice, however, had depleted the Zeros’ ammunition and saved the bulk of the fighters at Wheeler Field.

Meanwhile, Second Lieutenants Taylor and Welch, along with four squadron mates, were taking off from Haleiwa Field and heading toward the “large target” near Opana Point, while at Bellows Field ground crews were rapidly fueling and re-installing the hastily cleaned .50- and .30-caliber machine guns aboard the dozen P-40Cs. Of the major airfields, Kanoehe Naval Air Station was the most fortunate, being spared attack because the fighters and dive-bombers designated for it were searching for TF8 instead.

Zero fighters from Kaga opened the attack over Pearl Harbor by shooting down six of Enterprise’s Devastator (TBD) torpedo-bombers as they climbed southward from Ford Island. The Zeros then pounced on and destroyed four more TBDs and three Dauntless (SBD) dive-bombers on the Ford Island runway. Victorious over Ford Island, they winged their way to Ewa Field and destroyed the few Marine fighters and dive-bombers that had not been sent to Wake and the Midway Islands. At 7:55 27 Vals from Akagi and Kaga began their dives on Hickam Field, destroying the majority of the B- 17s and B-18s that were parked in the open. The 20 remaining torpedo-carrying Kates began their run toward Battleship Row from the southeast, flying over Fort Kamehameha and down the Southeast Loch.

Despite the warning, both Hickam and Wheeler Fields were defenseless. The anti-aircraft artillery units assigned to defend them were still in their motor pools at Schofield Barracks preparing to deploy. The Kate torpedo-bombers nonetheless ran into a barrage of .50- and 1.1-inch-caliber machine-gun and 3- and 5-inch anti-aircraft gunfire from the ships in Pearl Harbor. This fire was not as withering as it would become later in the war, when each cruiser and battleship carried dozens of 20- and 40mm anti-aircraft guns.

U.S.S. Oklahoma was the target of seven Kates. Her crew splashed two, but the modified torpedoes from the remaining five ripped out her port side. Rapid counter-flooding prevented her from capsizing, although she settled at a 30° list. West Virginia also received four torpedoes to her port side; however, her hits were more evenly spaced and she settled on an even keel. The three remaining Kates began their run on Nevada, but two were shot down and the third’s torpedo missed. California and the ships anchored on the western side of Ford Island escaped attack entirely because the force scheduled to attack them was among those heading south to intercept TF8.

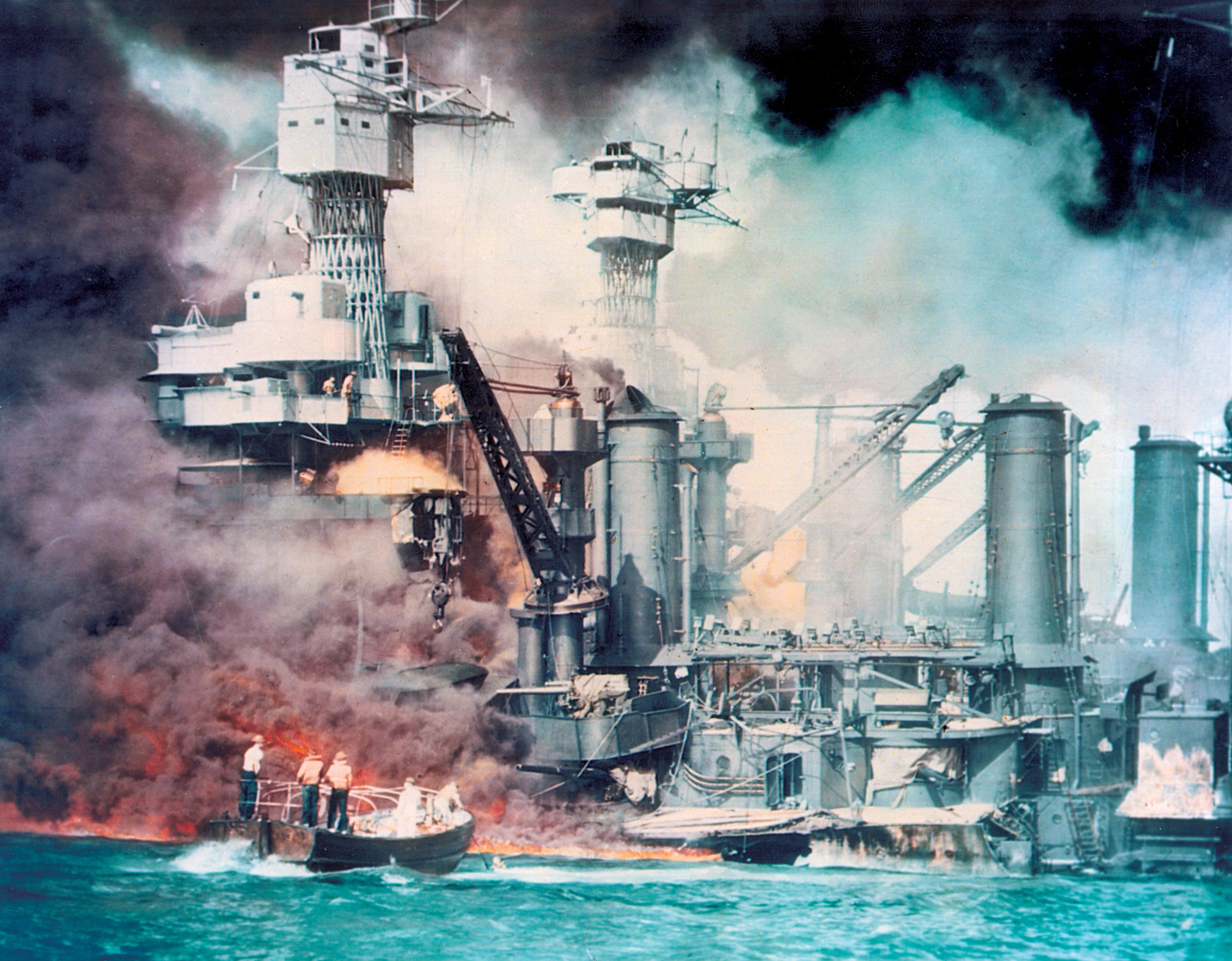

Minutes after the torpedo-bombers struck, the level-bombers began their run over Pearl. They carried armor-piercing bombs modified from 14-inch battleship shells. Their targets were the inboard battleships Maryland, Tennessee, and Arizona. Long hours of practice paid off. They made repeated hits on the battleships. At 8:20, Soryu’s Petty Officer Noboru Kanai placed a bomb through Arizona’s forecastle and into her forward powder magazine. The explosion that followed not only destroyed the battleship, but its concussion knocked sailors to the deck on all the surrounding ships. Admiral Kimmel watched in shock from his headquarters next to Southeast Loch, as the pride of his fleet sank into the 40-foot waters of Pearl Harbor—40 feet of water that was thought to have been too shallow for a torpedo attack.

Enterprise Is Discovered

The ad hoc strike group under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Shigeharu Murata separated from the main force at 7:45 to seek out TF8. They found their prey at 8:30, steaming south at 30 knots. On Enterprise and her escorts all hands stood at their battle stations. They had long since heard the radio message “Air raid Pearl Harbor. This is no drill.” Circling at 20,000 feet was their combat air patrol of 10 Wildcats. Enterprise’s 30 SBDs and six remaining TBDs were circling over the island of Maui, sent out of harm’s way by Halsey. His plan was to recall, refuel, and arm them to strike the Japanese fleet, once he had an idea of its location.

Commander Murata ordered his veteran torpedo pilots to split their force in half, his element engaging Enterprise while the others hit her escorts. The Vals were to strike after the Kates had made their run. Murata’s ten Kates began their runs at both sides of Enterprise, charging through a hail of antiaircraft fire much heavier than what their comrades were facing at Pearl. Three went down before launching their fish, but the remaining planes successfully loosed their torpedoes. Three hit Enterprise on her starboard side in quick succession, followed by another two on her port. She began to slow. Her advanced damage control design matched the effects of the five massive torpedo holes, but once the modified battleship shells dropped by the Vals exploded within her hull, destroying her watertight integrity, she began to settle slowly to the bottom of the Pacific.

Meanwhile her Wildcats had been engaged by the Zeros as they dove to attack the Kates. In a whirlwind fight, seven Wildcats went down, taking with them three Zeros and two Kates. The remaining Kates and Vals made their runs on the cruisers Northampton, Chester, and Salt Lake City. Swerving wildly and putting up a dense canopy of anti-aircraft fire, Chester and Salt Lake City took repeated hits and were soon ablaze and sinking. Of the nine escorting destroyers, Blach, Dunlap, and Benham were sunk. Northampton, flagship of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, escaped with one torpedo hit and one bomb strike.

His job done now that Enterprise was sinking, Murata led his strike force—less eight Kates, seven Vals, and three Zeros—back to its home carriers. The remaining U.S. destroyers rescued the survivors of TF8, Vice Admiral Halsey among them.

The Lull Between Strikes

The destroyer Helm, which had gotten underway before the attack, cleared the harbor entrance at Pearl at 8:17. She was followed by the destroyer Monaghan a few minutes later. Both had escaped being attacked during the initial assault. At 8:25, coinciding with the end of the first wave’s attack, the light cruiser Phoenix slipped her moorings and sailed through the harbor. She was not noticed, for all eyes were on Nevada. Taking advantage of Nevada’s standard practice of having one boiler on line when in harbor, Ensign Joseph K. Taussig, the officer of the deck that morning, ordered her remaining boilers fired up when General Quarters were sounded. It was his order that enabled Nevada to be the only battleship ready to sortie. With an ensign navigating, Chief Quartermaster Robert Sedberry piloted her down Battleship Row and into the main channel by 8:55. This was a masterful feat of seamanship, but one that would be for naught.

At 8:30 the Opana Point radar site reported another “50 plus” blip approaching Oahu on a southward heading. Kaaawa Station, now on the air, reported it, too. Both stations also reported smaller blips that were departing to the north-northeast. Major Bergquist relayed the new targets to Wheeler Field control so that it could direct the P-40s that had taken off to intercept them. Koko Head Station began reporting a scattered group of targets, approaching from the east. These were Major [Truman H.] Landon’s 12 B-17s just arriving from the mainland; four had turned back because of mechanical problems. Major Landon, who had heard the attack over the radio, contacted Hickam control for landing instructions. He was ordered to divert his flight to alternate airfields on Maui and Hawaii and to await orders to return to Hickam.

Commander Taylor relayed the information about the incoming Japanese flights to Rear Admiral Bellinger and Patrol Wing Two at Kaneohe Naval Air Station. Their presence confirmed the wisdom of Bellinger’s earlier decision to send the PBYs scouting to the north in search of the Japanese fleet. So far the eighteen PBYs that had gotten airborne had not yet encountered any Japanese aircraft.

The Haleiwa Field P-40s landed at Wheeler to refuel and rearm. They then took off with orders to patrol over Bellows Field, since the planes there were still not airborne. Twelve P-36s stayed over Wheeler Field as well, to serve as local air defense, but the 30 P-40s that had taken off from there after the initial attack were directed to intercept the inbound second wave. They spotted 150 Japanese planes flying below them at 8:40. Exploiting their altitude, they shot down two Zeros and half a dozen Vals and Kates as they dove through the surprised formation. Climbing back up to re-engage the enemy, however, they made the fatal mistake of engaging the nimble Zeros with classical dog-fighting techniques. As a result, 20 of their number never made it home. The remainder escaped after running out of ammunition. Many were damaged. The 34 remaining Zeros regrouped and raced ahead of the bombers, splitting to attack Bellows, Kaneohe, and Hickam airfields.

Fifty Vals arrived over Pearl at 8:55. Commander Fuchida ordered them to concentrate their attack on Nevada, which had just entered the main channel. The battleship’s antiaircraft guns opened fire but were too few to deter the attack. Having to steam straight and slow in the channel, the ship was racked from stem to stern with repeated bomb hits, some of which ripped through her armored decks and exploded in her interior, starting fires and knocking out her main electrical system. Minutes after being hit by the first bomb, she also took two torpedoes in the stern from one of the mini-submarines that had penetrated the harbor earlier that morning. The first hit destroyed her rudder and screws, while the second tore a 40-foot hole in her stern. Losing headway, she slowed to a stop in the narrowest Y-part of the channel, where she blew up 15 minutes later at 9:10, breaking her back.

With Nevada gone, the level-bombers and remaining dive-bombers shifted their attention to the battleships California and Pennsylvania, and the cruisers still at anchor. California took three torpedoes from lurking mini-submarines during this assault, which caused her to settle to the bottom of the harbor. The destroyer Alwyn sank one of the mini-subs with gunfire when it broached the surface after firing its torpedoes. A total of 15 Vals and Kates fell to anti-aircraft fire and the guns of the Marine Corps Wildcats that had arrived over the harbor from Ewa Field.

Bombers also struck Hickam again, destroying the few hangars not hit in the first strike and leveling the machine shops. The runway escaped damage, even though more of the planes there were damaged.

Second Lieutenants Taylor and Welch led the Haleiwa contingent of P-40s against the 20-plus Vals and Zeros that began their raid on Bellows Field at 9:00. Their aerial offensive broke up the attack and sent a half-dozen Vals crashing to the ground. Having experienced the abilities of the Zeros earlier, these pilots refrained from dog-fighting but instead dove to the attack and then zoomed away to gain altitude before re-engaging. Five of them drifted over Kaneohe Naval Air Station and into the midst of the attack there, where they surprised the Vals and Zeros in mid-attack. Several of the enemy went down. Meanwhile, the Zeros and Vals that had been interrupted in their attack on Bellows switched to secondary targets at Wheeler Field. After climbing to altitude, the Zeros swept down on the defending P-36s, effecting a near slaughter of the obsolescent aircraft. Even so, the P-36s kept the Zeros from strafing the field, restricting the damage there to a dozen bomb hits from the Vals, several of which hit the ball field, which had been planned originally as the location of underground gasoline storage tanks.

By 9:30 the second attack had ended, and the attackers had disappeared over the horizon. Radar tracked them to the north until they went out of range at 130 miles. En route home, the formation intercepted and shot down two of Patrol Wing Two’s PBYs, but not before one got off a location report that confirmed the continued flight north beyond radar range.

The Third Wave

Nagumo’s carriers began recovering the first wave at 10:00. At 10:30 the Admiral met with his staff to discuss initial attack reports and information radioed by Fuchida on the success of the second wave, which was still an hour out. Captain Genda proposed that Nagumo execute a planned third strike. The targets would be Pearl’s oil storage farm, submarine docks, headquarters, and maintenance shops. Nagumo was reluctant to risk his fleet by staying in the area for another strike. Genda countered that the sinking of Enterprise left only Lexington unaccounted for. Meanwhile the sinking of Nevada prevented the surviving cruisers and submarines from exiting the harbor, so there was no real surface threat to worry about.

Since Nagumo continued to fret, Genda suggested that he send scout planes to search to the west and south—the location of Lexington by his guess, since Midway Island was in that direction. Nagumo agreed that it was time to use the scouting force, ordering it launched. He delayed his decision on the third attack, however, until Fuchida returned and reported on the damage he had seen.

Commander Fuchida landed on Akagi at noon. He reported the attack results to Vice- Admiral Nagumo, emphasizing that the channel was closed and that what was left of the U.S. Pacific Fleet was trapped inside Pearl Harbor. He recommended the launch of a third strike immediately to take out the port’s oil tank farms and machine shops. There were also a number of submarines that had largely gone unscathed. The Zeros, he added, had shot down over 60 American planes and had left the remainder burning on the ground, eliminating any threat from that direction. After taking all of this in, Nagumo decided to launch the strike, but he emphasized that it would be the last and that the fleet would withdraw as soon as it returned. At 1:00 54 Zeros, 36 Vals, and 44 bombers took off.

Recovery and Search

The shock and devastation of the first two strikes had by then begun to sink in. Admiral Kimmel surveyed the burning and sunken hulks that had been the main battleline of the Pacific Fleet. He was further saddened by a report from Rear Admiral Spruance that Enterprise, two heavy cruisers, and three destroyers had also been lost. He found no solace in the fact that 30 of Enterprise’s SBDs had survived and would soon land at Ford Island. Most distressing of all was his realization that Pearl Harbor was useless, plugged by the wreckage of Nevada. His chief salvage officer had informed him that it would take several months to clear her, especially if she could not be refloated. It might, indeed, be easier to dig a new channel if equipment to do the job could be brought in from the West Coast. They could not even blow her up; she was too close to the Fleet Ammunition Storage Area for that.

Lieutenant General Short had less damage to deal with. Forts Shafter, Debussy, and Kamehameha had largely escaped attack, and Schofield barracks had received only minor damage. His antiaircraft batteries were now deploying to positions around Pearl Harbor and the two main airfields. Meanwhile, both of his infantry divisions were intact and moving to man beach defenses. Even so, Major General Martin’s Hawaiian Air Force was shattered. Martin had lost four of his six serviceable B-17s. Out of 36 obsolete B-18s only 11 survived, and his fighter strength was reduced to 25 P-40s and 16 P-36s. On the positive side, nine A-20 light attack bombers had escaped destruction, and the safe arrival of Major Landon’s 12 Flying Fortresses had given him a small but valuable heavy bomber force. Martin decided to get the B-17s back to Hickam Field and to prepare to attack the Japanese fleet if it could be located.

Commander Taylor informed Rear Admiral Bellinger that Army radar was tracking the Japanese planes as they returned to their carriers. Bellinger relayed this and the PBY report to Admiral Kimmel, who ordered the information to be relayed to Lexington along with orders for it to seek out and engage the Japanese fleet. He also ordered the SBDs to be recalled and readied for launch once the fleet was located.

The Final Strike

At 1:45, one of Patrol Wing Two’s PBYs found the Japanese fleet steaming on a north-northeasterly course, 170 miles north of Oahu. It had just missed seeing Nagumo’s third wave head south to strike Pearl. Receiving word of the discovery, Rear Admiral Bellinger notified Admiral Kimmel and Major General Martin. Martin ordered his B-17s to take off immediately, and Kimmel told Bellinger to send Enterprise’s 30 Dauntlesses. They would be striking at maximum range, but he would chance that. Neither group had a fighter escort.

The Air Warning Center had received a month’s worth of training that morning and was functioning better than Major Bergquist had hoped. Again it was Lockard and Elliot at Opana Point who picked up the first track of incoming Japanese aircraft at 120 miles. Bergquist called Major General Martin, who ordered the 25 flyable P-40s to take off and orbit at 20,000 feet over Wheeler until they received instructions to intercept the attack. Meanwhile, the leader of the incoming Japanese, Commander Murata, split his 60 fighters, ordering half of them to range ahead to clear the skies of enemy interceptors. The other half would fly escort.

Martin’s radars detected the splitting up of the Japanese force and the AWC relayed both locations to the orbiting Tomahawks. Captain James O. Beckwith, commander of the 72nd Pursuit Squadron, led his fighters against the larger formation, the melee beginning at 2:35, 20 miles northeast of Kaneohe Bay. Again the P-40s had an altitude advantage over their prey. They dove through the Japanese formation, shooting down six to ten Vals and Kates, but were then pursued by the Zero escort. During the next 20 minutes the Zeros shot down half of them.

For the first time that day, Army antiaircraft greeted the attackers when they arrived over Pearl Harbor. The leading Zeros had already strafed Hickam Field and the ships in the harbor to divert attention from the bombers. Eighteen Vals dived on the tank farms at either end of the naval station between Hickam Field and the Southeast Loch. Carrying conventional 550 kg bombs, they ripped a number of fuel tanks open, starting massive fires. The remaining 18 dive-bombers hit eight submarines moored side by side in Southeast Loch, next to the Submarine Headquarters building. They also hit the cruisers Honolulu, San Francisco, and New Orleans, all of which had escaped serious damage during the first two attacks.

Unknown to the Japanese, Admiral Kimmel had established his Pacific Fleet headquarters in the Submarine Headquarters Building the previous summer. The Admiral preferred to operate from ashore in order to free his flagship for full duty with the fleet. When the headquarters was struck by three 1,000-pound bombs, Admiral Kimmel and many of his staff were killed. Unintended as it was, Kimmel’s death would provide America with her first hero of the war and her first winner of the Navy Cross. Kimmel had, after all, gone down with his ships. Performing as level-bombers, the Kates next rained bombs on machine shops near a dry dock that held the Pacific Fleet’s flagship, U.S.S. Pennsylvania.

Having destroyed the fleet’s fuel reserves and her heavy repair shops, Murata led his force back to their carriers. However, Kimmel’s death did not go unavenged. At the very moment when Murata was completing his mission and turning his force homeward, the Flying Fortresses found the Japanese fleet and launched their attack.

Major Landon’s Flying Fortresses justified their name that afternoon by fending off the attacks of the 24 Zeros defending the fleet and absorbing intense antiaircraft fire from below. However, his hopes of sinking the carriers with the six 600-pound bombs each plane carried came to nothing. Dropped from 25,000 feet, they failed to score a single hit.

The Zeros were still swarming around Landon’s B-17s when Enterprise’s SBDs arrived and began slow but deadly dives on the enemy below. The ill-advised decision of the captains of Zuikaku and Soryu to cease evasive maneuvers and launch more Zeros attracted the attention of both Scouting Six and Bombing Six. These walked their bombs the length of both carrier decks, ripping open their vitals and setting off gasoline, torpedoes, and bombs aboard planes being held in readiness to strike Lexington. The price was high for the Americans, though, only eight of their aircraft making it back to Ford Island. Several more had survived the encounter with the Japanese fleet, but fell prey to the Zeros of Murata’s returning strike force when their paths crossed.

The four intact carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Shokaku, recovered the returning planes at 5:00, taking aboard the orphans from Zuikaku and Soryu. After the recovery was completed, Vice Admiral Nagumo ordered the fleet to head north-northwest and back to Japan. He had been right in his worries. The August war game had correctly predicted the loss of a third of their planes and two carriers. He left behind two cruisers and four destroyers to rescue the survivors of the sinking carriers.

The destruction of Zuikaku and Soryu was a bittersweet victory for the Americans, for the Pacific Fleet had ceased to exist as a battle force. One carrier and seven battleships had been sunk, the harbor entrance at Pearl was blocked, the machine shops were destroyed, and the fuel reserves were gone. Although there remained 25 PBYs and 14 B-17s, only a dozen P-40s were left that were serviceable. The Hawaiian Islands lay open to another aerial assault. The remainder of TF8 steamed into Honolulu Harbor the next morning, but the port was too small to serve as more than a temporary shelter for the Pacific Fleet’s cruisers and destroyers. It could not hold a fleet. Lexington’s TF12 arrived on the 9th. Vice Admiral Halsey, who had assumed command of the Pacific Fleet, ordered the carrier to Long Beach, California, taking the damaged Northampton with it. With the closing of Pearl Harbor, America’s defenses shrank back to the West Coast, leaving the U.S. with the terrible dilemma of fighting a war in the Atlantic at the same time as it tried to rebuild its Pacific Fleet. Pearl Harbor would not be reopened until April 1942. Unfortunately, that was exactly when Yamamoto arrived with the Japanese Combined Fleet.

The Reality

The warning phone calls by Stark and Marshall, of course, were never actually made. It was later discovered that the transoceanic cable had been tapped by the Japanese. U.S.S. Enterprise was delayed by two days of bad weather which resulted in her being 200 miles west of Oahu on the morning of the attack. The state of the Hawaiian Air Force was as presented, including both the Navy and the Army aircraft being on four-hour alert. However, the unintentional benefit of this was that although most of the aircraft were lost, the pilots survived the day. Nevada was ordered not to sortie and grounded herself at Hospital Point, where she sank, thus leaving the channel open.

Pearl Harbor survived as a forward striking base for the Pacific Fleet, which, stripped of its old battleships, was reformed around fast carrier groups. The alternatives played out here show that changing very little other than that of the mind-set of the Army and Navy commanders in Hawaii and in Washington could have changed the historical outcome of December 7, 1941. n

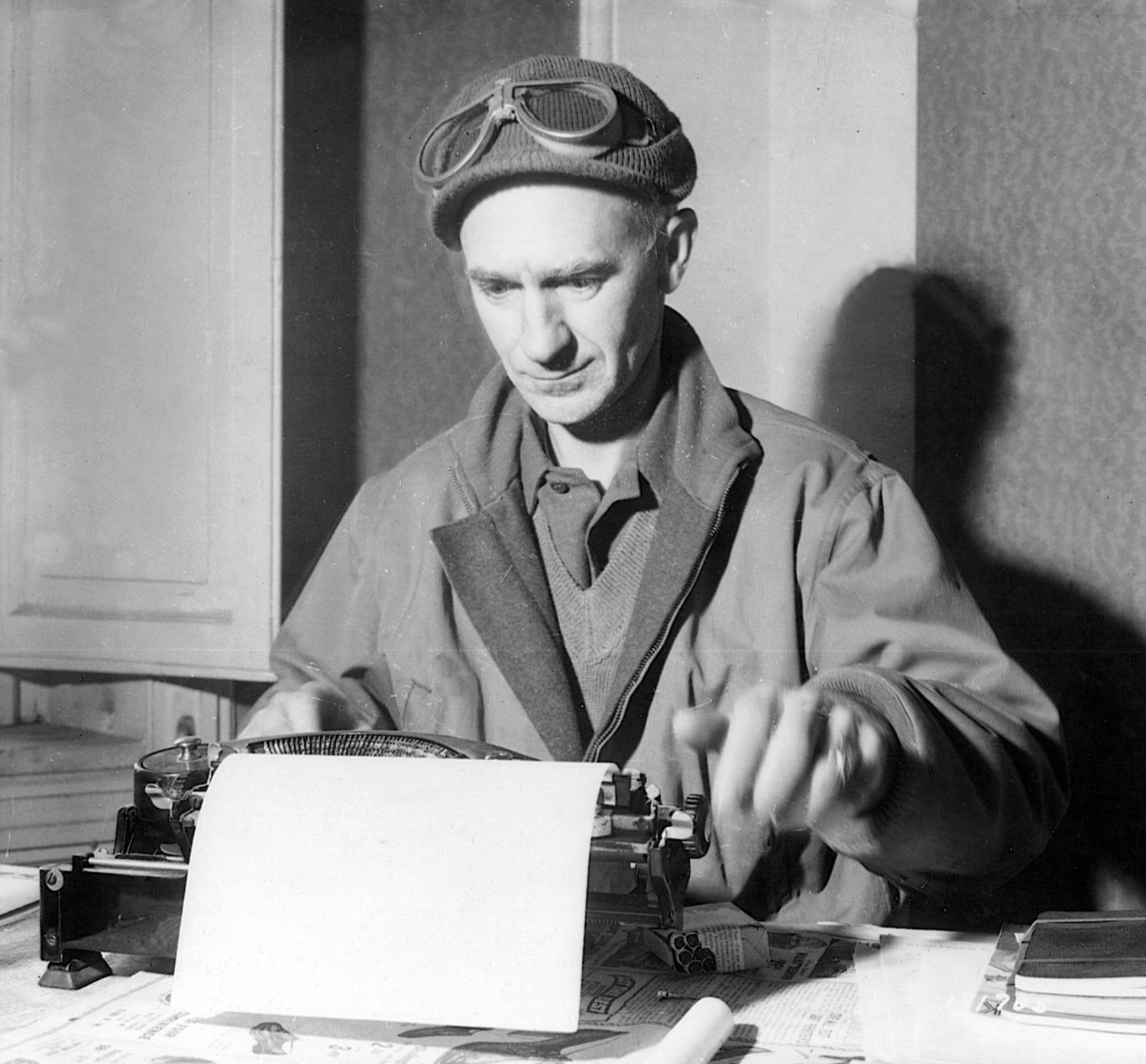

Frank R. Shirer is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History at Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. He served 20 years in the Army. He also worked as a Soviet analyst at the Defense Intelligence Agency and as an order of battle analyst at the Army Intelligence and Threat Analysis Center.

This well written article is one of the reasons I dislike alternative history. There are many battles, maybe a majority, that have turned on happenstance rather than claimed superior planning. Although lessons can certainly be learned from them, they probably don’t offer much assistance in planning future similar operations considering possible unknowns. The decision regarding Little Round Top during the Civil War is just such an example. Conversely, Pickett’s charge was simply bad planning that could have gone no other way. The decision not to launch the third strike by the Japanese to take out repair and oil storage facilities was an example of poor decision making but if done probably would have had a long term effect of only extending the length of the war, not the final outcome.