By Sam McGowan

Although the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was the event that served to galvanize America to fight World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt and his military advisers had pervasively decided that defeating the Japanese would be secondary to destroying the Nazi war machine in Europe.

The U.S. War Plan Orange called for a defensive strategy in the Pacific based on naval operations to relieve the Philippines, but by 1939 the Army and Navy had pretty much decided to cross the faraway islands off the list and concentrate on a defensive line from Panama to Hawaii to Alaska. When war came, Roosevelt committed the United States to following agreements made with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin to concentrate the primary Allied effort against Nazi Germany.

When Germany was defeated, the Allies would turn their efforts toward defeating the Japanese. Yet, in the final analysis, Japan had pretty much already been defeated by the time the German capital of Berlin fell to Russian troops in April 1945. How—considering that military planners had expected to take as much as two years after the defeat of Germany to bring Japan to her knees—had the Japanese been pushed back to the defense of their homeland in far less time than anyone expected?

One answer is that the United States possessed a dual weapon that was as yet unknown—the apparatus that became the Far East Air Forces and the pugnacious character of a diminutive Army Air Corps officer named George Churchill Kenney.

On July 7, 1942, Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney received a telephone call from Army Air Forces commander General Henry H. Arnold ordering him to come to Washington for a briefing on a new and important job. There are two ironies about Kenney’s selection as the man who would ultimately be responsible for turning American military efforts in the Southwest Pacific from a defensive to an offensive strategy: The first is that another name had been recommended to General Douglas MacArthur, that of the flamboyant, newly promoted, general officer James H. Doolittle, who had just returned to the States after leading the famed American bombing raid on Tokyo. MacArthur had turned Doolittle down, considering the famed aviator to be nothing more than a showboat. Doolittle would go on to achieve some degree of additional fame in a secondary role as a numbered air force commander in Europe. The second irony is that just before he got the call from Arnold, Kenney had finished chewing out a young fighter pilot for buzzing the Golden Gate Bridge and flying his Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter low over the streets of San Francisco. Kenney would get to know young Lieutenant Richard Ira Bong intimately in coming years, and would recommend him for the Medal of Honor as America’s top-scoring ace fighter pilot.

George Kenney arrived in Australia in late July to find the Allied forces organized for a strictly defensive role. The Allied lines were on the south coast of Papua, New Guinea, just north of the town of Port Moresby. Several months before, in March 1942, Japanese troops had landed on the north side of the Lae Peninsula and had begun advancing south over the rugged Owen Stanley Mountains toward Moresby. The Battle of the Coral Sea thwarted Japanese plans for an amphibious assault on Moresby, but the troops coming overland had advanced to within a few miles of the capital city before they were halted by Australian troops.

Fierce fighting raged along the Kokoda Track, a narrow mountain road that spanned the Owen Stanleys between the Allied base at Moresby and the newly established Japanese base at Buna on the shores of the Huon Gulf. An attempted Japanese landing at Milne Bay was repulsed by Australian troops, thanks to Allied radio code-breakers who learned of the planned landings in time for the garrison to be reinforced.

Shortly after his arrival in Australia, General Kenney was introduced to the man he would later identify as his own “secret weapon.” Two days after officially taking over as the “air boss” on General MacArthur’s staff and activating the Fifth Air Force, Kenney flew to Charter Towers to visit the 3rd Light Bombardment Group, formerly known as the 3rd Attack Group. Kenney had a background in attack aviation himself, and he sympathized with the young airmen in the group who chafed at the recent redesignation that had taken away their attack identity.

While the general was visiting with the group, its commander, Lt. Col. John H. “Big Jim” Davies, took Kenney to meet “The Mad Professor,” a recalled former U.S. Navy petty officer pilot who was now Major Paul Irving Gunn, U.S. Army, but was more commonly known as “Pappy.” Pappy Gunn had been impressed into the Army at Manila the day war came to the Philippines, and had already made a reputation with the young American flyers in Australia for his daring deeds in the opening days of the war.

Gunn had been placed in charge of the Air Transport Command when he arrived in Australia, but after the ill-fated Java Campaign he had more or less attached himself to the 3rd Light Bomb Group. In addition to flying transport missions for the Air Transport Command, Gunn, who is a true legend of the Pacific War, flew combat missions in a B-25 with the men of the 3rd. When he wasn’t flying, he could often be found helping the mechanics keep the group’s airplanes in the air. In the summer of 1942 he was helping the group ready its recently arrived A-20 light bombers for combat.

Kenney found Gunn working on his latest innovation—installing a package of four .50-caliber machine guns in the nose of one of the Douglas A-20 attack bombers that had recently arrived in Australia for the 3rd Bomb Group. With a reputation as an innovator himself, Kenney was impressed by Gunn’s concept, especially when the old Navy petty officer told him that the guns came from wrecked fighters.

Prior to leaving the United States for Australia, Kenney requested that a supply of parachute-fragmentation bombs that he had developed be sent to Australia. When he saw Pappy Gunn’s modifications of the A-20, he asked the former machinist’s mate if he could formulate some kind of bomb rack to carry the bombs. When he explained to Gunn what the bombs were designed to do, the former sailor’s eyes lit up.

Gunn was fighting his own personal war with the Japanese since his wife and four teenage children were all interned at the former St. Thomas University near Manila. He had but one goal—to defeat the Japanese as quickly as possible and free his family. Recognizing the potential of a man like Gunn, Kenney ordered the former Arkansas sharecropper’s son to report to him in Brisbane when he had finished the conversion, to take a place on Kenney’s personal staff. He instructed Gunn to convert 16 A-20s into low-altitude strafer/para-frag bombers and to do it within two weeks.

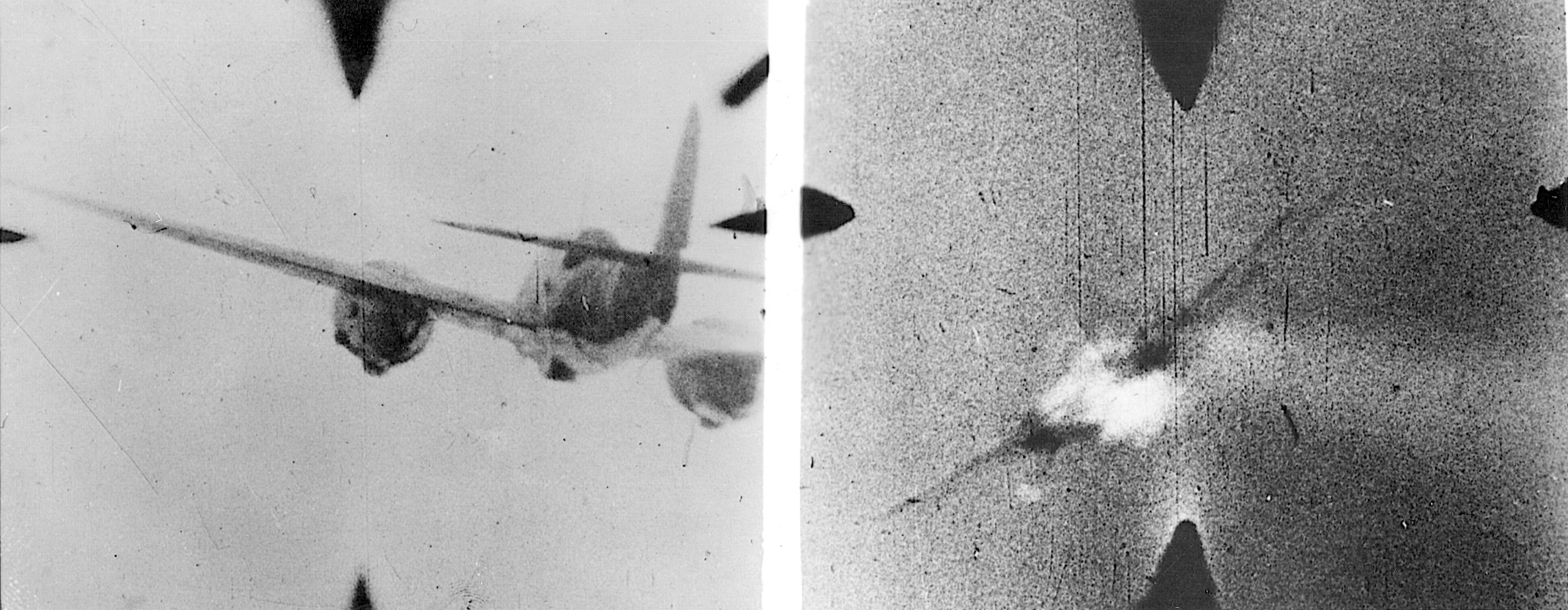

By early September all of the A-20s had been converted, and on the morning of September 12 they made their combat debut. They changed the face of the war in the Pacific immediately. Captain Don Hall of the 8th Bomb Squadron led a flight of nine converted A-20s on a low-altitude mission against the Japanese airfield at Buna. A flight of 12 Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters led by Captain Tommy Lynch escorted the bombers.

Each bomber crew had been briefed to remain 20 seconds behind the airplane in front of them to avoid being caught by shrapnel from the exploding fragmentation bombs. Previously, Allied bombing missions had been flown at medium altitudes, but the flight of A-20s came in over Buna right down on the treetops, taking the Japanese defenders by surprise. The fierceness of their attack so demoralized the Japanese that, by the time the third flight of two airplanes came over the strip, all return fire had ceased. The attackers claimed 17 Japanese airplanes, mostly Aichi Val dive-bombers, and signaled the dawning of a new day in the war in the Pacific.

Prior to the conversion of the A-20s, Allied air power in the Southwest Pacific Area of Operations had consisted of a handful of war-weary Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, a few Martin B-26 Marauder bombers, and a squadron of North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers that had been literally stolen from the Dutch. Fighter strength was made up of Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks and the P-39 Airacobras, supplemented by P-400s, which were a special version of the P-39 that had been designed for export overseas.

Air transportation consisted of two ad hoc troop-carrier squadrons flying a menagerie of airplanes, including converted B-17s, a pair of B-24A transports, and some Lockheed C-60s as well as several variations of the Douglas DC-2 and DC-3. Before he left for Australia, Kenney was promised a fighter group flying P-38s. Kenney had made sure that the young lieutenant he had chewed out in his office in California on July 7 was one of the pilots. He had also been promised a troop-carrier group equipped with C-47s.

Kenney had come to Australia with orders to begin an offensive campaign against the Japanese in New Guinea, but he had also been told that he would have to operate on a shoestring. Unlike most of the other prewar officers who would rise to prominence during the war, he was not ingrained in the daylight precision-bombing philosophy. Kenney was a tactician, one whose theories would become major features of the postwar military, and his tactics centered on the use of air power as a “force multiplier,” to purloin a 1990s military buzzword. This was accomplished by using the airplane to advance the Allied lines as far forward as possible as quickly as possible. His philosophy was to take the war to the Japanese rather than waiting for them to bring it to the Allies.

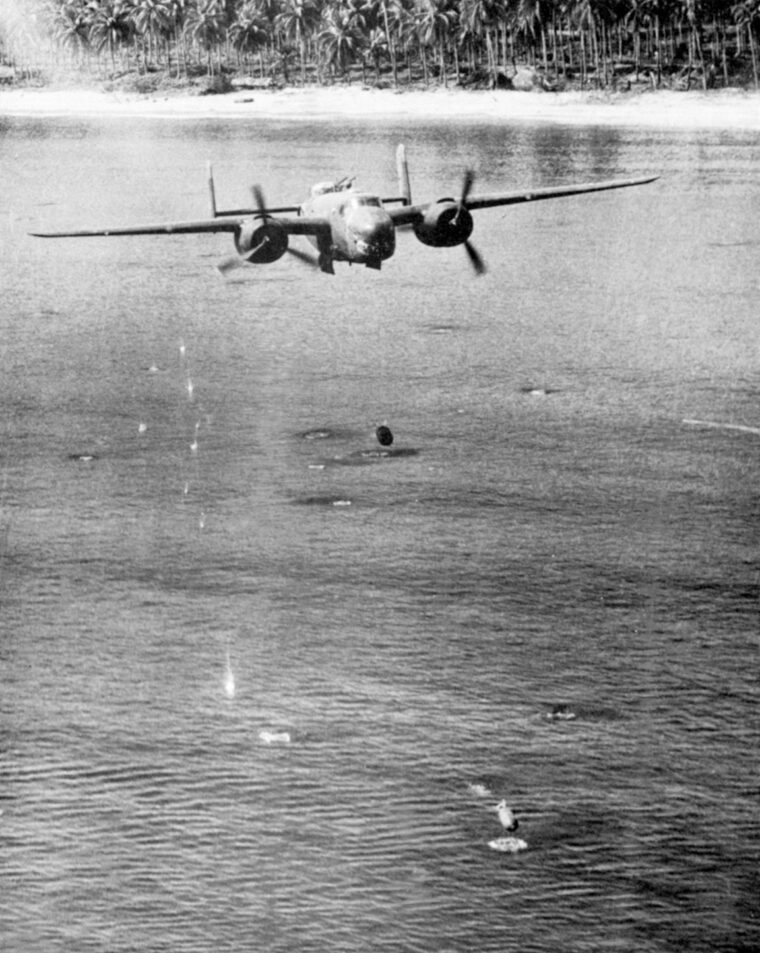

While en route to Australia, Kenney and his aide, Major Bill Benn, borrowed a B-26 and experimented with a technique called “skip- bombing.” This involved dropping a bomb at low altitude in such a way that it would skip across the water like a thrown pebble to slam into the side of a ship. Soon after their arrival, Kenney sent Benn to take command of a B-17 squadron and to teach the pilots the new method of attacking shipping.

Benn would be reported missing while on a raid less than six months later, but in the interim he had taught the pilots of the 63rd Bomb Squadron well, and skip-bombing had become a major part of Fifth Air Force bomber tactics. Kenney was pleased with the success of the skip-bombing B-17s but felt that they were not the right airplane for the job. He was awaiting the results of Pappy Gunn’s latest effort, but it would be several weeks before it would be introduced to the war.

Kenney’s tactical inventiveness also included efforts to improve the use of the airplane to enhance the capabilities of ground troops.

Immediately after assuming command of the Fifth Air Force, he had gone through the Army Air Forces in Australia with a sharp sickle, weeding out officers who lacked the enthusiasm or skill to function as leaders in a combat zone where the mission was to carry out offensive operations on a shoestring budget. Kenney wanted “operators,” men like himself who were willing to take calculated risks and perform innovative feats in order to get the job done.

One of the feats Kenney had in mind was to introduce the troop-carrier transport into the ground war. The American 32nd Infantry Division had arrived in Australia, and Japanese psychological warfare specialists were having a field day dropping leaflets telling the Australian troops fighting in New Guinea that the Americans were taking care of their wives and girlfriends while they did the fighting and dying.

Kenney suggested to MacArthur that he put his transports to work flying some of the American troops north to New Guinea so they could have a presence that would improve the morale of the Australian troops. Although his staff did not like the idea, MacArthur gave Kenney the go-ahead to move the first regiment of the 32nd Infantry forward after the air boss pointed out that it would take two weeks to move the division up by ship.

On September 15, U.S. Army Air Forces transports began moving the first elements of the 126th Infantry Regiment to Port Moresby. The airlift went well, but the rest of the regiment had already begun boarding ships. MacArthur approved the movement of the 128th Infantry Regiment entirely by air, with the airlift commencing at the same time the ship carrying the 126th was scheduled to leave Brisbane.

Kenney had two days to assemble every available transport airplane in Australia for the airlift. To supplement the transports of the 21st and 22nd Troop Carrier Squadrons, he rounded up an assortment of airplanes, including Australian civilian transports and recently arrived bombers with their civilian ferry crews.

The airlift went off with few problems, and the presence of the American reinforcements served to boost the morale of the Australian troops who had been fighting on the Kokoda Track for several weeks. The timely arrival of the airlifted reinforcements led General Thomas Blamey, the Australian officer in charge of the troops in New Guinea, to stop talking about possibly withdrawing into the confines of Port Moresby.

Kenney’s experiment with airlifting troops from Australia into the combat zone was a preamble to his larger plan, to use airlift to move Allied troops across the Owen Stanleys to seize an “airhead” at Wanigela Mission, a station located on flat coastal lowlands on the Lae Peninsula. Kenney wanted to build an air base on the north side of the mountains from which to launch air raids against Rabaul and Lae. From such a forward base, aircraft would not have to climb above mountain peaks that reached 13,000 feet. Reconnaissance flights had revealed that only a token force of Japanese was in the vicinity of the planned airfield. Even though he knew the ground officers on MacArthur’s staff would oppose the plan, Kenney felt sure that his idea for Operation Hatrack would be approved.

Shortly after the movement of the 128th Infantry to Port Moresby, General Henry H. Arnold arrived in the theater on an inspection tour. Kenney told Arnold that the 19th Bomb Group—both air and ground crews—was worn out, and that he would like to exchange them for the 90th Bomb Group, a brand new outfit equipped with B-24D Liberator bombers that had recently arrived in Hawaii. Arnold approved the swap.

When Arnold asked him about the problems of maintaining two different types of bombers, Kenney replied that he did not care. He would take whatever he could get. The daylight bombing crowd in England preferred the B-17, but Consolidated Aircraft and Ford Motor Company were gearing up to turn out B-24s at an unprecedented rate. Within a year, all of the

B-17s in the Southwest Pacific had been replaced by the longer range B-24s.

MacArthur did approve Kenney’s plan for Hatrack, and in early October a former Australian missionary named Cecil Groves flew into Wanigela Mission and put local natives to work cutting a strip in the kunai grass long enough for C-47s to land. Planeloads of Australian infantry began arriving the next morning, and by nightfall a battalion of approximately a thousand men had been airlifted across the Owen Stanleys to land without opposition on the north slopes of the rugged mountains.

The Australians established an air base only 72 miles south of the Japanese base at Buna, and the Allies began moving in supplies. Troops began moving overland from Port Moresby, and on October 14, Fifth Air Force troop carriers began airlifting the U.S. 128th Infantry into the new strip. An Australian force was moving as quickly as possible through the mountains toward Buna over the Kokoda Track. After the troops were in place, they attempted to find an overland route northward, but the terrain was too swampy and the 32nd Division elected to establish a new airstrip at Pongani, which was barely 20 miles from Buna itself.

Surprisingly, the American troops had not encountered any Japanese; apparently they were concentrating their efforts on the Kokoda Track and did not realize they were being threatened from the south. Kenney believed that Buna was so lightly defended that the U.S. troops could take it with little resistance, and General Ennis Whitehead, his subordinate, had suggested a subsequent attack on Nadzab to flank the Japanese at Lae.

However, the Navy halted 10 C-47s that were on their way to Kenney, thus cutting into Fifth Air Force resources and ruling out an attack at the time. Before an attack could be launched, the New Guinea rainy season arrived, slowing down the Allied advance and allowing the Japanese to bring in reinforcements from the sea. Buna was not captured until early January. By that time the Japanese had turned Lae into a major stronghold.

While the modified A-20s were proving to be formidable attack weapons and the C-47s were demonstrating the mobility of ground forces, the new Fifth Air Force was still lacking the effective fighter capability to achieve air superiority. Throughout most of 1942, the only fighters operational in the Southwest Pacific were P-39s and P-40s, both of which were inferior to the nimble Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighters. They were effective at low altitudes, but the tiny P-39s lacked the climb and high-altitude performance to allow them to intercept Japanese formations; the P-40s were unable to maneuver with the Japanese fighters.

Kenney had been promised a fighter group equipped with twin-engine P-38s, which arrived in Australia in September. However, it was not until the very end of December that they made their combat debut, due to design problems that had to be rectified in the field. On December 27, 1942, 12 P-38s intercepted a formation of 20 Japanese fighters and seven dive-bombers in the vicinity of Dobodura.

By the time the fight ended, a dozen Japanese aircraft had gone down, with a loss of only one damaged P-38 that crash-landed at Dobodura (it was repaired and returned to service). The pilot, Lieutenant Ken Sparks, was credited with two Japanese planes that day, as were Captain Tommy Lynch and Lieutenant Richard Bong, whom Kenney had chewed out a few months previously.

Four days later, the P-38s engaged a formation of the infamous Zero fighters and shot down nine of them, leading General Whitehead to claim, “We have the Jap air force whipped.” World War II in the Pacific had taken another major turn.

While the ground forces were focusing on Buna, the Fifth Air Force was carrying out its own offensive against the Japanese. Skip-bombing B-17s from the 63rd Bomb Squadron were achieving a great deal of success against Japanese shipping, but Kenney restricted their activities to moonlit nights due to their lack of forward-firing guns. Meanwhile, the modified A-20s were proving highly effective against both Japanese airfields and in support of the ground forces. A major success for the A-20s was the destruction of the wire-rope bridge at “Wairopi” (pidgin English for wire rope). Dozens of Japanese troops were killed in the attack, including the Japanese commander, General Tomitaro Horii, who fell into the raging Kumusi River and drowned.

The success of the A-20s convinced Kenney that the answer to the skip-bombing problem lay in a similar conversion of the B-25. Major Gunn had suggested converting the B-25s when he first met Kenney, and he was given the go-ahead to convert enough to equip a squadron.

The conversion of the B-25 provided for eight forward-firing guns (later increased to 14 on production aircraft), including six in the bombardier’s compartment and two more mounted on pods alongside the fuselage. After the first airplane had been modified, it was given to the commander of the 90th Bomb Squadron, Captain Ed Larner, to try out. Eleven others followed.

The first mission of the converted B-25s was directed at Japanese shipping, but when no ships could be found, Captain Larner led the six-plane flight in a low-level attack on the Japanese airfield at Salamaua. The B-25 proved to be as effective as the converted A-20, and was an even more formidable weapon since it packed more firepower in the nose.

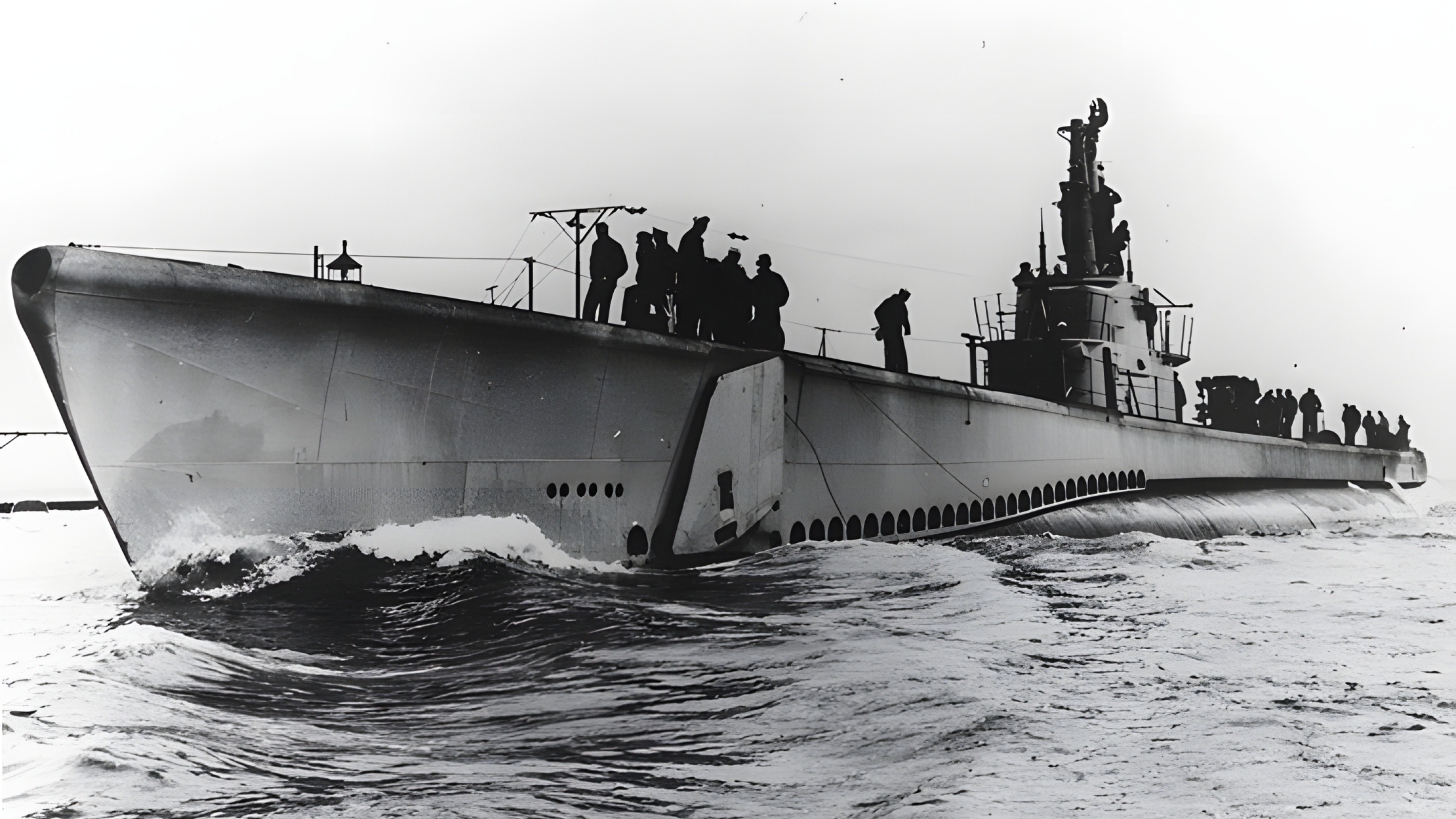

During the first week of March, the A-20s and B-25s proved just how effective they could be against shipping during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. This was a battle that naval historian Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison referred to as “the most devastating air attack against shipping of the war, excepting Pearl Harbor.” A Japanese convoy made up of eight transports escorted by an equal and possibly greater number of warships was attacked repeatedly on February 28 and March 1. During a running battle, every one of the transports was sunk.

Although some success was achieved by B-17s attacking at medium level on February 28, the low-level skip-bombing attack by a squadron each of B-25s and A-20s achieved the lion’s share of the victory. Every transport and four of the destroyers were either sinking or badly damaged after the first attack, and a second attack later in the day finished off the convoy. A U.S. Navy PT-boat attack later sank one damaged vessel. Only two destroyers survived the battle.

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea proved that air power could effectively interdict the enemy’s supply lines, leading Kenney and MacArthur to decide on a new strategy. The Navy command in the South Pacific had been successful in its landings on the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, and these forces were working their way northward an island at a time toward the Japanese bastion of Rabaul on the island of New Britain.

Kenney convinced MacArthur that Allied forces could defeat the Japanese in New Guinea and the Solomons, bypassing heavily defended areas such as Rabaul, then neutralizing their effectiveness by cutting off their lines of supply through air attack and sea blockade, combined with a constant air offensive against Rabaul itself. In order to do so, the first priority was to capture Japanese territory and establish advance airfields from which bomber squadrons could operate.

The attack on Nadzab airfield in the Markham Valley northwest of Lae was designed to establish an Allied force in the Japanese rear. Kenney and his staff reasoned that the airfield could be captured by an airborne force supported by a massive air attack. For the attack to succeed, the Allies needed an airfield close enough to Nadzab for previously positioned ground troops to be airlifted in to exploit the advantage gained by the airborne assault.

Kenney and the Fifth Air Force planners decided on a site in the vicinity of Marlinan, a station in the Papuan interior only about 30 miles south of Lae on the north slopes of the Owen Stanleys. After finding other potential sites unsuitable for airfield construction, Lieutenant Everett Frazier, a young American engineering officer, walked into Marlinan, then walked back out to make his report. He found that the old strip was subject to flooding and thus unusable as an advance base, but it could serve as a supply point for materials that could be flown in to construct a new airfield at another site near the village of Tsili-Tsili.

After some preparation of the field, troop-carrier C-47s began flying men and building materials into Marlinan. Jeeps and trailers were airlifted over the mountains to transport the supplies to the construction site some two miles away. To speed up the flow of supplies, Fifth Air Force cargo handlers conceived the idea of sawing the frames of Army trucks in half, then loading each half aboard a C-47 and reassembling the truck after it was airlifted to the other side of the mountains. The concept worked so well that all of the trucks in the region were eventually modified to be disassembled for airlift.

To preserve the secrecy of the new airfield, the C-47 crews operated at low level beneath the Japanese radar screens, but their presence was eventually discovered. The first flight of C-47s to arrive with aviation support personnel was attacked by Japanese fighters, which shot down two of the transports before they were driven off by U.S. pursuit planes.

Once the airfield at Tsili-Tsili was complete, a date for the attack on Nadzab was set. The 503rd Parachute Infantry had arrived in Australia and was in position for the assault. A ground attack was launched on Lae on September 4, and the following morning the men of the 503rd boarded 79 54th Troop Carrier Wing C-47s at Port Moresby. After assembling over Thirty-Mile Aerodrome, the assault force crossed the Owen Stanleys and moved into drop formation over Marlinan.

Just before the first troops jumped at 10:22 am, a formation of B-25s attacked the airfield with para-fragmentation bombs and machine guns. A flight of A-20s laid down a smoke screen over the airfield, and the paratroopers jumped into the Papuan skies. The Japanese defenders were so demoralized by the strafing attack that the airfield was captured in a matter of minutes, with little resistance.

Generals MacArthur and Kenney observed the show unfolding from positions in B-17s that orbited overhead. Kenney reported that MacArthur “jumped up and down like a kid” when he realized the success of the operation. After the drop, the C-47s headed for Marlinan where they picked up loads of Australian infantry and airlifted them into the new airhead at Nadzab. The airlifted troops formed one arm of a pincer that was rapidly closing around the Japanese base at Lae. By September 16, Lae was in Allied hands, along with Salamaua, a position a few miles to the south.

With the rapid fall of Lae, the way was open to accelerate plans for a landing at Finschafen. The date of the landings was moved up by three weeks, and Allies secured the beachhead on September 22. The town itself fell within two weeks. Meanwhile, the Allies began a buildup around Nadzab, establishing no less than four aerodromes by mid-November. Their inland location required that all resupply be by air for several months, which made living conditions at the bases rather spartan.

Sparse accommodations or not, the new bases moved the Allied aerial advance farther forward as the fighter squadrons that flew out of them were able to extend air superiority up the New Guinea coastline. By the end of 1943, a doctrine had developed in the Southwest Pacific under which “the offensive fighter line” would move forward with the aid of air transport to extend the “destructive effort of bombers.” Air and seaborne ground forces would seize and secure ground for advance air bases, with air support being used to protect their flanks.

By this time the U.S. Navy was beginning to recover from the terrible losses of its carriers in the sea battles of early 1942, and replacements were taking to the seas. Carrier-borne naval aviation forces would provide air cover for ground operations that were beyond the reach of land-based aircraft, while naval bases would be established under the protection of land-based fighters. The recipe for winning the war in the Pacific had been established.

After Nadzab, the Fifth Air Force began a campaign to reduce the defenses of Cape Gloucester, on the northwestern tip of New Britain, where the Marines were planning a landing. Rabaul was on the opposite end of the island. Instead of mounting a direct attack against Rabaul, MacArthur, at Kenney’s suggestion, elected instead to isolate the Japanese garrison and to destroy its combat effectiveness through a massive aerial campaign. U.S. Navy carrier aircraft joined with Fifth and Thirteenth Air Force land-based bombers in a series of attacks on the airfields and installations around the city. By the end of February 1944, the Japanese air and naval forces at Rabaul had been reduced to the point that victory could be declared.

North of Lae on the Huon Peninsula were several Japanese airfields and installations, with Hollandia, a town on the northern coast of New Guinea, serving as their supply base. Instead of capturing the intermediate positions, the Southwest Pacific command decided instead to capture Hollandia itself, thus leaving the positions that depended on the supply base to “wither up and die on the vine,” in Kenney’s words.

In February 1944, Kenney concluded that the Japanese had abandoned Los Negros, a small island in the Admiralties in the Bismarck Sea. Seeing an opportunity to seize a base for bombers to support an attack on Hollandia, Kenney convinced MacArthur to order a reconnaissance in force with the objective of occupying the island if they met no opposition. After elements of the 5th Cavalry landed on the island, MacArthur flew in and looked the place over, then declared that the Allies would stay. Kenney had his forward base for heavy and medium bombers.

The Allies had also conceived Operation Reckless, a bold plan to leapfrog more than 200 miles into Japanese territory and seize Hollandia. With operations in the South Pacific winding down, the disposition of the forces assigned there had been discussed. Kenney had put in a bid for the 13th Air Force, and Arnold had granted his request.

Within days of the Allied occupation of Los Negros, Thirteenth Air Force B-24s had moved onto the island. In preparation for the landings, a massive air campaign was conducted to neutralize the Japanese defenses at Hollandia. Nadzab was the primary base for Fifth Air Force B-24s as well as specially modified P-38s that had been equipped with additional fuel tanks to extend their operational range.

Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet, equipped with new, fast, Essex-class aircraft carriers, was detailed to conduct air strikes on Japanese targets in the vicinity. Wewak, a major Japanese installation south of Hollandia, also fell under intense attack. By early April, Japanese air defenses at Wewak and Hollandia had been rendered ineffective, and on April 21 Allied troops began landing with little opposition.

General Douglas MacArthur’s objective from the moment he set foot on the PT boat that evacuated him from the Philippines before the fall of Corregidor was to return and liberate those islands. The capture of Hollandia put his forces almost within striking range of the Philippines. Hollandia placed Allied bombers in striking range of Japanese bases at Noemfoor, on the northwestern tip of New Guinea, and Biak, a small island off the coast. By the end of June, Noemfoor was in Allied hands.

On July 4 Kenney received a godsend when famous aviator Charles Lindbergh arrived in New Guinea. Barred from military service by personal order of President Roosevelt because of his role in the Isolationist Movement during the interwar years, Lindbergh had made a major contribution to the war effort on the manufacturing side with Ford Motor Company and United Aircraft. He had come to the Pacific as a factory technical representative for United to work with U.S. Marine fighter squadrons flying the F4U Corsair.

Lindbergh was also ordered to gather information on the performance of the twin-engine P-38s. Kenney reasoned that Lindbergh would be able to help his P-38 pilots extend their effective range and gave the civilian more or less carte blanche to operate within the theater. There was one exception. Lindbergh was not to operate in areas where there was great likelihood of combat. Lindbergh told Kenney he could increase the range of the P-38s by 50 percent, which would extend their combat radius from 400 to 600 miles. Lindbergh was true to his word. The effective range of the P-38 was increased, and some pilots were able to operate as far as 700 miles away from their bases.

The establishment of B-24 bases in northern New Guinea brought Japanese installations in the southern Philippines in range of U.S. heavy bombers. The extended-range cruise techniques Lindbergh had taught the P-38 pilots enabled them to fly escort. To secure an advance base closer to Mindanao, the original objective for the return to the Philippines, the Allies elected to capture Morotai, an island in northern Indonesia. Morotai fell into Allied hands in early October.

In addition to providing a base from which to launch an invasion of the Philippines, the capture of northern New Guinea allowed Allied bombers to wage a strategic bombing campaign against the oil refineries at Balikpapan on Borneo and in the Netherlands East Indies. Kenney had asked General Arnold for a heavy bomber group equipped with long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortresses for the task of destroying Balikpapan, but Arnold had other plans for the huge bombers and refused to allow any to be under theater control.

While the distances involved were on the edge of their range, B-24s flying from Biak were able to reach the refineries. Several attacks were flown against the refineries in October 1944, and by the middle of the month reconnaissance photos indicated that they had been effectively destroyed.

With New Guinea and the Solomons in Allied hands and the few Japanese installations south of the equator isolated by air and sea power, a political war erupted between MacArthur and the Navy over the next objective. While MacArthur believed that the Philippines, an American possession at the time, were the logical next objective, the Navy thought otherwise. As MacArthur’s forces were advancing steadily northward through New Guinea and the Solomons, the Navy and Marines concentrated their initial efforts in the South Pacific, then began moving northward through the tiny islands that make up the archipelagoes of the Central Pacific.

By the late summer of 1944, the Mariana Islands were in Allied hands, and construction of bases for B-29s was under way. The Navy believed that the Allies should invade Formosa next, bypassing the Philippines, which would be in range of U.S. land-based aircraft in the Marianas. MacArthur argued that the Filipinos were, in fact, Americans, and it would be a crime to leave them under Japanese occupation. The argument became moot when Admiral Halsey’s carrier pilots encountered only light resistance in the Southern Philippines, leading him to suggest a landing at Leyte instead of Mindanao as had been discussed.

Allied troops landed on the island of Leyte on October 20, 1944, two years and three months after George Kenney arrived in Australia to bring order out of a chaotic and even demoralized Allied air force. He went there knowing that his theater was low on the priority list and that he could expect very little support from the War Department, which was focused on defeating the Germans.

Kenney had an innate ability to get the most out of the resources available, however, and to improvise when necessary. He also had the ability to pick the right people as subordinates and was not hesitant to send packing those who were not able to fight the way he knew was necessary to win the war in the Pacific. He had his secret weapons, men like Ennis Whitehead, who served as the Fifth Air Force advanced commander in New Guinea, then became the Fifth’s commander when the Army Air Forces in the Pacific were reorganized.

Many of the successful operations that made the reputation of the Fifth Air Force were conceived and planned by Whitehead and his staff. Then there was the group and squadron commanders, men such as Bill Benn, Roger Ramey, Tommy Lynch, and Neal Kirby, who led their pilots in combat and, in many cases, gave their own lives to defeat the Japanese.

It was no accident that many of the top-scoring U.S. Army aces were Fifth Air Force men—Lynch, Tommy McGuire, Kirby, and the ace of aces, Richard Bong, who shot down 40 Japanese aircraft during the course of the war.

Kenney was an innovator, and he was also able to seek out and attract others such as the irrepressible Pappy Gunn, the man who designed the innovative weapons that helped lead to Kenney and MacArthur’s successful strategy to win.

Sam McGowan is the author of The Cave, a novel of the Vietnam War. He has also written extensively on the subject of air transport during World War II.

I think one strategic advantage for the US is innovation and flexibility.

Are there examples among Japanese leaders who were as creative technologically, strategically, and tactically as men like Kenney and Gunn?