By Allyn Vannoy

Just after releasing their bomb-load, flak slammed into the B-17, causing it to go out of control, falling fast. Tail gunner Ken Tucker saw the sky rushing by and knew their luck had finally run out.

He had come a long way since that infamous day: December 7, 1941. Kenneth S. Tucker had only been 16, living in Eastpoint on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where his father owned and operated a wholesale seafood business.

During World War II, many young men joined the armed forces at 17 if their parents consented. Tucker felt he could serve better if he first graduated high school; besides that, his parents would not agree to let him join up.

In May 1943, Tucker turned 18, graduated from high school, registered with the draft board, and volunteered for service. After three months of waiting, he arrived at Camp Blanding, Florida, on August 20, where he was sworn in and given a series of tests that included the Army General Classification Test—the Army’s IQ test—as he looked to join air cadet training.

His basic training at Keesler Field, Mississippi, was cut short after just seven weeks as he was ordered in November to Morehead State Teachers College in Minnesota. An accelerated program, it was to provide an equivalent of two years of college in just six months, covering basic courses in English, math, physics, history, geography, weather, and political science. There was also pilot training using Piper Cubs. But Tucker found some difficulty with his flight training instructor.

In March 1944, Tucker was ordered to report to Santa Ana, California. But less than two weeks after he arrived, he was told that the USAAF had too many personnel in air-crew training. Tucker and his squadron would be removed from training and given a choice of other fields that were experiencing shortfalls.

The order ended Tucker’s chance to become an officer, but he was tired of training and classrooms—he wanted to see action. His options were aircraft mechanic, radio operator, or armament. The desire for the shortest school led Tucker to choose armament—and an eight-week gunnery school in Kingman, Arizona.

After finishing gunnery school in June, Tucker received his wings and promotion to Private First Class.

His next stop was Lincoln, Nebraska—a staging area for assignments. From there he headed for Alexandria Army Air Field, Louisiana, for B-17 air-crew training. At his barracks he met his pilot—1st Lt. Louis Dunigan—along with the rest of the crew he was assigned to. Like most bomber crews, they were a mixture of educational backgrounds, ages, hometowns, and personalities.

Dunigan was from Casper, Wyoming, a graduate of the University of Wyoming, and had enlisted before Pearl Harbor. He had begun training as a fighter pilot, but rapid changes in altitude gave him sinus problems, so he transferred to multi-engine aircraft. Dunigan was 27 years old, married, didn’t drink, smoke, or use profanity.

The co-pilot was 2nd Lt. James W. Garrison of Norfolk, Virginia. Like Dunigan, he didn’t drink, smoke, or curse. He was engaged to be married.

The navigator was 2nd Lt. Halsey S. Nisula of Gardner, Massachusetts, near Boston. He was 23, quiet and had worked in a grocery store before enlisting. Nisula was responsible for guiding the aircraft from base to target and back, but also was to call out crew oxygen checks every 10 minutes, and also kept the aircraft’s flight log. Mission success depended on the skill of the pilot and navigator and their ability to work together.

Flight Officer Donald H. “Mac” McQuistion was the bombardier. He was from New Jersey and had attended Rutgers University. Trained in the use of the top-secret Norden bombsight, he saw to its operation and also its security.

Tech Sgt. Clyde Dwight, Jr., was the flight engineer and top turret gunner. He stood behind the pilot and co-pilot and monitored engine and aircraft performance when not operating his gun. Dwight, 27, was a tall Texan, married with a daughter. Before enlisting, he had worked in the oil fields near his hometown of Pampa, Texas.

The radio operator was Sergeant Malcolm Vignes, from Louisiana. Vignes sat in a compartment just behind the bomb bay where he operated a set of radio transmitters/receivers, and also had a single .50-caliber machine gun that pointed aft and skyward.

Lieutenant Dunigan told the four gunners to sort out which positions they would man in the aircraft, but suggested that the shortest of the four, 18-year-old Pfc. Jack B. Taylor, from Beaumont, Texas, should take the ball turret. Another, Corporal Michael E. Joyce, requested one of the waist guns because he suffered from claustrophobia and the tail position was too tight.

That left Tucker and Pfc. Kenneth Snow. Neither had a preference, but Snow volunteered for the other waist-gun position and Tucker was fine with the tail gunner’s spot.

Joyce, 27, the right-waist gunner, was an Irishman from Holyoke, Massachusetts. He was married with a small son. Snow, 18, was from Oklahoma and took the left waist gun.

To reach his position in the tail, Tucker had to crawl through a tunnel-like opening and then ease down onto a bicycle-type seat. It was tight, with little room to move about. In rough skies, the tail gunner could get bounced around and become airsick. He was also isolated from the rest of the crew, only able to communicate via the plane’s inter-phone. Tucker, who considered himself somewhat of a loner, felt comfortable in the tail.

Ground-school training consisted mostly of aircraft recognition and crew procedures, followed by in-flight training. During training, Lieutenant Dunigan had the gunners come onto the flight deck, one at a time, to get a feel for the aircraft. Dunigan would place the bomber on autopilot and have them sit in the pilot’s seat. Lieutenant Garrison would act as the instructor and teach them how to control the plane. Tucker was surprised at how sluggish and slow to respond it was, but he enjoyed his time behind the controls.

Towards the end of their training, they conducted both day and night flights. During this time they found out that Nisula was an excellent navigator. At the same time, Dunigan displayed his calm and confident ability to command. Tucker also noted how well the crew members worked together as a team—their skill and dedication. Dunigan’s crew, one of 50 or 60 in the training cycle, receiving the Most Outstanding Crew Award.

As they completed crew training and prepared to head overseas, orders were received that one of the gunners was to be left behind; they were told that there were extra gunners overseas. When Dunigan asked for a volunteer to stay behind, no one stepped up. So, the wing commander ordered Snow to remain behind.

The squadron took a train bound for Lincoln, Nebraska on October 10, 1944. There they received a shiny new B-17G. The “G” model was modified from the “F” model with the addition of two .50-caliber machine guns, operated by the bombardier, mounted in a chin turret under the aircraft’s Plexiglas nose. The crew conducted two test flights to check out the plane. Next, the squadron flew their new Fortresses to Grenier Army Airfield, New Hampshire.

From Grenier, they were instructed to take off separately and fly to Gander Lake, Newfoundland. There they waited three or four nights until a weather front over the Atlantic cleared. Heading east over the ocean, they had instructions not to open sealed orders until two hours after departure. When Dunigan opened the orders, they learned that their destination, after several stops en route, was Gioia [del Colle], Italy, along the Adriatic coast, about mid-way between the cities of Bari and Taranto.

Their stops on the way to Italy were Lajes Field in the Azores, then Marrakesh, Morocco, and Tunis, Tunisia. Finally arriving at Gioia, they were trucked to Foggia and then on to their base at Amendola, about 10 miles to the northeast, where they were assigned to the 414th Bomb Squadron of the 97th Bomb Group, part of the Fifteenth Air Force.

The Fifteenth Air Force had been activated on November 1, 1943, from groups that were originally assigned to the Twelfth Air Force’s Bomber Command. Transferred from Tunisia to Italy in December 1943, it was organized into three combat wings, six heavy bomber groups (BGs), five medium bomber groups, and four fighter groups.

Of the heavy bomber groups, the 2nd, 97th, 99th, and 301st flew B-17s as part of the 5th Bomb Wing; added to this later was the 463rd and 483rd bomber groups. Other groups were equipped with B-24s.

Unfortunately, Tucker’s crew lost their B-17G upon arrival, as it was reassigned to another crew. They christened their replacement aircraft “Kwiturbitchin.”

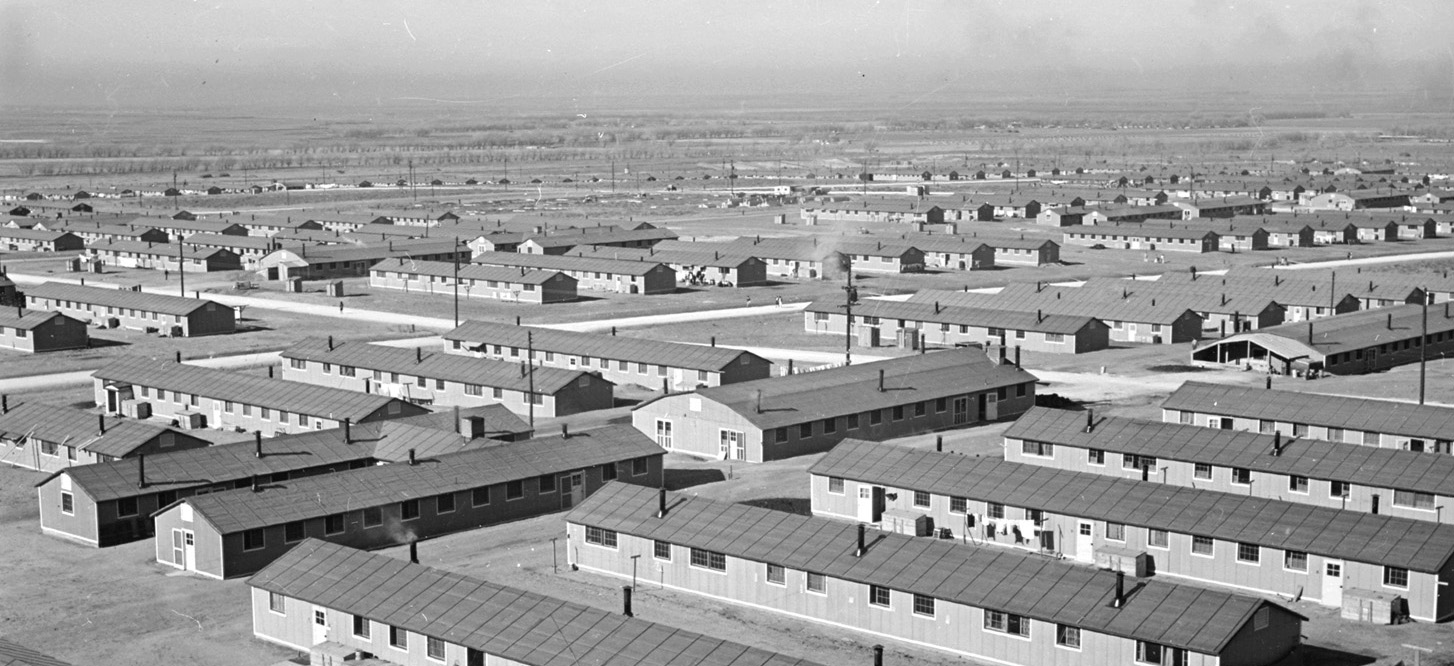

Arriving in dark and rainy weather, they found conditions at Amendola rough. The enlisted men were issued a tent and cots and shown a place to set up. To deal with the muddy ground, they used the wood from discarded ammunition boxes to create a floor in their tent.

The latrine and showers were more than 100 yards from their tent. There were no sidewalks, just a muddy path. The mess hall was a somewhat more positive note. The cooks seemed to do the best with what they had. There was no fresh food, only canned, dried, or powdered. Chili sauce was used to make powdered eggs palatable. And there was always fresh, hot coffee.

The first day at their new base they were given an orientation briefing. A first sergeant gave a rundown of the base rules and regulations, and an intelligence officer provided an overview on what to do if they survived a crash landing or bailed out into enemy territory.

What surprised Tucker was information about the Ustashe (Ustaša–Croatian Revolutionary Movement). During the German occupation of Yugoslavia, the extremist group ruled Croatia, just across the Adriatic, and the Yanks were told that if they were captured by the Ustashe, their best hope was to be turned over to the Germans. The Ustashe were said to be a sadistic group that murdered Orthodox Serbs and Jews; they were to be avoided at all costs.

The base had few permanent buildings. An old brick farmhouse had been converted into squadron operations housing and an orderly room, intelligence office, and medical facility. A large barn had been turned into the Group Headquarters. Other buildings, the mess halls and service clubs, had been built of limestone.

Sergeant Dwight, the crew’s flight engineer, turned out to be a very good scavenger, turning up with the parts to make a heater for the crew’s tent.

The airfield’s runway was made of Marston mats—perforated steel sheets—but was not in the best condition.

Tucker learned that the 97th had the reputation of having the best ground crews in the Fifteenth Air Force. There were a dozen planes per squadron; each B-17 had a crew chief and four mechanics. Tucker witnessed their dedication to their work, their long hours, and the pride they took in the success of their planes. Ground crews would be disappointed if one of their planes had failed to complete a mission, or turned back due to mechanical problems; it was an especially sad day if their plane failed to return from a mission.

Tucker had great praise for the Boeing B-17 aircraft. Crews were confident that the Fortress would get them to the target and back. If necessary, the B-17 could fly on just three, sometimes even two, engines. Even shot full of holes, the B-17 was so well built that it was often able to make it home.

Since they had arrived without a left-waist gunner, a substitute was assigned. One of those was Earl Whit. On the return from a mission with Whit, he asked if he could be permanently assigned to the crew; he thought the crew was the best he had seen. Lieutenant Dunigan checked with the rest of the crew and they were all happy with Whit.

But that could not be said about the radio operator, Vignes. While good at his job, his bunk area was sloppy and he rubbed others the wrong way. Sergeant Dwight presented the crew’s case to Dunigan, who told the operations officer to remove Vignes from the crew. A permanent radioman was not assigned.

Tucker thought a lot of his crew, recalling that “on every mission, I was always so thankful for our crew. The teamwork and dedication displayed by each and every one of those guys was second to none. There was no doubt in my mind that they were each going to play a huge role in getting us all back alive. My biggest fear wasn’t of dying—my biggest fear was letting my crew down. There may have been 10 of us, but when we got in that plane and prepared for takeoff, we were one.”

The weather played a key role in operations—both over the Alps and near the base; sometimes they were grounded for days. The delays frustrated their efforts to reach their 35-mission goal and return home. Some missions were scrubbed due to bad weather even as the crews were waiting for takeoff clearance. And there were times after takeoff when they were recalled to base due bad weather over the target and having to hazard a landing with their bomb-load still onboard.

On the ground, mud was a constant problem. Not only on the roadways and in the bivouac area, but mud would accumulate on the tires during taxiing and takeoff and freeze at altitude. On one landing, the right tire of Tucker’s aircraft had been hit by flak, but the frozen mud hid the damage. When the tire blew upon touch down, Dunigan gunned the left engines and was able to clear the runway for the following aircraft.

When having to fly through fog, pilots had to loosen up the formation in an effort to avoid a mid-air collision. Once clear of the fog, the pilots hurried to close up the formation. There was concern that German fighters could be waiting on the other side of the fog to jump a bomber that had become separated from the group.

The pre-mission routine began early. Even though crew rosters were posted the night before a mission, the crews never seemed quite prepared for the morning wake-up call between 2:30 and 4:30 in the morning. Once dressed, they headed to the mess hall for breakfast, then returned to their tent to grab their gear.

The crews assembled in the Group Briefing Room where they were shown a large map of central Europe, a black ribbon marking the route to the target. An operations officer would go over aerial photos of the target, provide details of flak and fighters. An intelligence officer would brief them on the best escape routes if they crashed or had to bail out. A meteorologist briefed them on the weather to the target and over the target area.

The pilots then met with the operations planner to work out their positions in the formation. The navigators, bombardiers, and radio operators met with their leads to discuss any issues and instructions related to the mission.

Next, they were driven to the crew shack to get their flying clothes and electric suits, parachute harness, “Mae West’ life vest, oxygen mask, and escape kit. The kit included a compass, knife, maps, matches, and first-aid kit.

The crews were then trucked to their planes. As the driver approached a hardstand, he would shout the last three digits of the plane’s serial number. If it was the crew’s assigned plane, the driver would stop, the crew would jump out, and haul their equipment to the plane. The pilots and flight engineer would already be there, performing their pre-flight check. Shortly before takeoff, a jeep would pass by and the driver would toss out a case of K-rations for the in-flight meals.

The ground crew chief would invariably call out, “Bring my plane back in one piece!”

On a green light from the airfield’s control tower, the crew boarded and got ready for takeoff, the pilots and the flight engineer going through the cockpit checklist before starting engines. Once the engines were started, they moved into line for takeoff.

“The biggest concern was staying warm at high altitude, where the temperature could reach 50 degrees below zero,” Tucker recalled. “Deaths from hypothermia and serious injuries from frostbite were a very real concern. As cumbersome as they were, our heated suits were a life saver.”

To protect their hands, crew members wore silk gloves, then electric gloves, and finally fur-lined leather gloves. They wore leather helmets with built-in earphones. Oxygen masks were plugged in as well to keep them from freezing up. A Colt .45 pistol was worn in a shoulder holster. On top of all this was a flight jacket.

To this was added their “Mae West” and their parachute harness, but the parachutes were set nearby. A flak vest and helmet were also at their combat station and only put on when approaching flak-possible areas, as the vest weighed 22 pounds.

Once the control tower had fired a green flare, they began to taxi out to the runway for takeoff. As soon as the first plane lifted off, the next plane immediately started its takeoff roll. The bombers went into a circling pattern as the others were getting airborne, organizing themselves into formation.

With the sky crowded with circling planes, forming up could be quite dangerous in fog or low clouds. The goal was to be formed up by the time they’d crossed the Adriatic.

Depending on the mission, the bombers would form into their squadrons, groups, and wings. The 97th Bomb Group would usually fly four squadrons of seven planes each. The squadron’s seven planes would form up in a box or diamond shape. The bomber at the top of the diamond was “the lead” and the one at the bottom was “the tail.” The lead planes always carried the highest-ranking pilot.

The last plane in the formation—dubbed “Tail-End Charlie”—was the least desirable position, because that plane was the most vulnerable to an attack from behind by enemy fighters.

Tucker flew his first combat mission on November 19, 1944, but not with the crew he’d trained with. It was standard practice to fly the first mission with an experienced crew. For Tucker, flying with a group of strangers was quite stressful.

Rookie gunners were supposed to fly at either of the waist positions. A veteran crewman was to assist the rookie, but instead Tucker was placed in the tail, and he questioned whether he was really prepared for combat.

The target for the day was Munich, on the other side of the Alps. The formation made it over the snow-capped peaks without any problems but, as the bombers approached their target, the sky seemed full of flak bursts. After returning to base, the ground crew assessed damage to the aircraft, counting 102 holes in the bomber’s skin.

With so many planes in close proximity, there was always the danger of mid-air collisions. During a later mission, Tucker’s aircraft was trailed by one flown by an inexperienced pilot, the plane in a lower position behind Tucker’s. When flak was encountered or enemy fighters were spotted, the rookie pilot would move in close enough that Tucker could look the rookie and his co-pilot in the eye.

Tucker contacted Dunigan over the plane’s inter-phone and asked him to call the nearby pilot and to tell him to back off. The rookie would drop back, but then, when conditions got rough again, he would close the distance again. Tucker called Dunigan again to report the situation.

Dunigan suggested Tucker “wobble” his twin .50s at the rookie, showing he meant business.

“That’s exactly what I did, and he backed off all right; and he stayed back—way back,” Tucker recalled. “Guess it took looking down the barrels of the two .50-caliber machine guns for that guy to realize that he better stay off our butt.”

During missions to targets in Germany, the bombers passed near the city of Udine in northern Italy, where there was an airfield with Italian pilots that continued to fly for the Germans. The Italian fighters almost never challenged the bombers because the B-17s maintained a tight formation.

On one occasion, the Italians did take off and approached a straggling bomber. When Tucker’s group leader saw what was happening, he directed Dunigan’s aircraft into a 360-degree turn to cover the straggler. As soon as the enemy fighters saw them coming, they turned away.

Escort fighters were greatly appreciated by the bomber crews. Tucker said, “Our favorite escorts were the P-51s from the all-black Tuskegee Fighter Group.” (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2023.)

Lieutenant Garrison was an “eagle-eyed” co-pilot, who scrutinized approaching fighters to make sure they were escorts and not enemy interceptors; the Germans were known to repair downed Allied aircraft and then use them to monitor and report bomber air speed and altitude to their flak gunners as they approached a target.

On one occasion Garrison thought a lone P-38 didn’t look quite right. So Dunigan contacted the commander of the fighter escorts and reported on the odd looking P-38 that was flying opposite their group. The rogue fighter soon peeled off and disappeared.

Approaching a target area, the bombers never flew directly to the Initiation Point (IP), but instead made a wide turn to approach the target. The bomb run started when they turned on the IP, lasting about three to five minutes. When the bombardier turned on his bombsight, he took over control of the aircraft, announcing, “Bomb-bay doors opening.”

After the bomb load was released (“Bombs away!”), the radio operator would then look into the bomb bay to make sure that all bombs had been dropped. The bombardier would close the bomb-bay doors, followed by the radio operator’s verification that the doors were closed.

Enemy fighters would usually approach from directly ahead and above. The FW 190 pilots would roll over as they dove on the bombers so that they could use their armor-plated bellies for protection.

During a raid on the Rublin oil refinery south of Berlin, after having released their bomb load and coming off the target, Tucker spotted a fast-moving aircraft approaching at “Seven o’clock level, going around toward nine.”

He then saw two more coming up from straight behind—“Six o’clock level.” Tucker and the tail gunner in the neighboring plane opened fire. The three aircraft were Me 262 jet fighters that streaked right through the squadron.

Flak was the worst nightmare for the bomber crews. The 88mm flak guns were feared due to their accuracy. The crews knew what size the shells were by the color of the smoke from the shell bursts. If black, it was an 88mm shell, if white it was a 105mm shell.

Tucker’s 10th mission was on Christmas Day, 1944. The target was the Brux oil refinery in northern Czechoslovakia—well defended and dreaded by the bomber crews. But before they reached the primary target, bad weather caused them to switch to an alternate target.

They flew past the alternate target at about 28,000 feet and then turned back on their route to strike it. When over the target, they dropped their bombs but then felt a tremendous jolt; their B-17 had been hit. The plane went out of control and started falling fast.

“I remember holding on for dear life and looking out the Plexiglas and seeing the sky whiz by,” Tucker said. “There was no doubt in my mind that we were done for. I clearly remember thinking: ‘This is it; our luck just ran out.’”

But before the scenes of his short life could play out before him, the plane stopped plunging and leveled out.

Over the plane’s inter-phone, Tucker and the crew could hear Dunigan and Dwight struggling to assess the damage to the aircraft. Flak had taken out the right-inboard engine. Dunigan had just feathered it when they were hit by a second round of flak that shattered the feathering mechanism of the left-inboard engine. It started windmilling—turning freely. The runaway prop increased drag, slowing the aircraft.

When they were able to reach the Adriatic coast near Yugoslavia on two engines, Dunigan told the crew to prepare to ditch. The U.S. Navy had ships stationed in the Adriatic to pick up ditched crews. But the sea was so rough that Dunigan reconsidered ditching, while the coastal terrain appeared too rugged for the crew to parachute.

As a last resort, he made the decision to try to make it to the island of Vis, just off the Yugoslavian coast. It was occupied by partisans and a few American troops had carved out a crude airfield for crippled bombers that couldn’t make it back to base.

As they approached they found they had no hydraulics and no flaps. There wasn’t time to turn and come back against the wind, so they had to make a downwind landing—nearly unheard of for a B-17. There was no real runway, just rough terrain where there had once been a landing strip. Miraculously, they landed safely.

As the crew tried to climb out of the aircraft, they found their way blocked by three very large women—dressed in olive-drab uniforms, armed with submachine guns, draped with bandoliers of ammunition, and wearing caps with the Communist Red Star.

A Yugoslavian sergeant then appeared, greeted the crew in English, and said he was responsible for taking care of Allied aircrews. He had been raised in Chicago and had returned for a family visit when fighting broke out. Caught in the country, he was drafted into the Yugoslav Army.

The sergeant took them to a group of American soldiers—a captain, eight enlisted men, and a cook. They had been sent to the island with a bulldozer to scrape out another emergency landing field. The next day, a C-47 was able to make a landing—delivering supplies for the partisans and picking up downed aircrews. By December 28, Tucker’s crew had returned to Italy and were back in the air.

On another mission near Munich, Tucker’s crew witnessed three unusual smoke trails rising from the ground. They appeared to spiral or spin. Later, it was learned that they were rockets fired from the ground. The rockets were estimated to be 12 feet long and exploded with a large cloud of white phosphorus smoke.

After each mission, the flight gear had to be returned to the equipment room. Where the crews exited, a medic was seated behind a small stand. Beside him were a ledger, a bottle of American whiskey, and a shot glass. Those who wished could stop and have a shot.

Initially, Tucker thought the shots were offered to help settle frazzled nerves, but subsequently learned that it was intended to loosen up the crews during post-strike interrogations. The interrogation, or interview, took place at Group Headquarters where each crew met with an intelligence officer. They were questioned about the intensity of enemy fighters and flak. Bombardiers were asked about bombing accuracy. The navigators went over the mission log with the intelligence officers.

The Red Cross set up just outside the interrogation area serving coffee and donuts. But if a mission was really rough, most crewmen just wanted to get back to their tent and get some rest.

If crews wanted a break, they could get a ride into the town of Foggia, about 10 miles away, and spend time at the USO Club. While there, Tucker’s crew became friends with a group of Australian gunners.

“There was something about their free-spirited attitude that I liked,” Tucker said. “I was telling one of my Australian buddies how much we enjoyed their company but didn’t particularly care for the Royal Air Force fellows. His response was, ‘Frankly, old boy, we don’t either.’”

Tucker’s 20th mission, February 1, 1945, was to Vienna. The city was heavily defended, with intelligence reporting 360 anti-aircraft guns. As expected, the flak was heavy, intense, and accurate. As they turned off onto the bomb run, there was a flak burst close by the aircraft.

Tucker immediately felt the concussion of the shell blast and was slightly dazed. When his senses returned, he felt a burning pain in his arm and discovered that the plane’s rudder cable was cut.

Dunigan called to check on Tucker, who told him that his arm was hurting pretty badly and that there were other problems. Dunigan, at the controls, realized what the problem was. Dunigan told Garrison to get the first-aid kit and directed Tucker to move to the radio room.

Tucker told Dunigan his wound could wait until they cleared the flak. Once out of the danger zone, Tucker shed his flak vest and oxygen mask and made his way to the radio room; Whit, the left-waist gunner, moved back to the tail. When Garrison checked Tucker over, he found a small entry wound just below the shoulder of his left arm.

From the burning sensation deep in his arm, Tucker realized he’d been hit by a piece of shrapnel. Whit returned from the tail with Tucker’s flak vest, showing a huge rip in the canvas covering in the middle of the back of the vest. Garrison and Whit believed that it had been hit with a piece of flak about the size of a fist. They seemed surprised that Tucker had survived.

With the cut rudder cable, Dunigan, who was flying squadron lead, called the other aircraft in the formation and informed them that he would be making a wide turn because of the rudder problem. Meanwhile, Dwight was able to use his tools to repair the cable and they proceeded without further problems.

After returning to base, Doc Remley, the group’s flight surgeon, examined Tucker’s wound and determined that a small fragment of the aircraft’s aluminum skin had penetrated Tucker’s skin. Remley decided to leave it and told Tucker that it would probably work itself out.

The doctor supervised and scheduled rest camp visits. He made a point of checking in with all the pilots to see if any of their crewmen were having any problems or were showing signs of combat fatigue. If there was a concern about any of the crew members, Doc Remley would schedule them for a rest camp visit.

After their 22nd mission, Tucker’s crew was sent for a week of well deserved rest at the Isle of Capri, off the west coast of Italy. The crew greatly enjoyed their time there.

Tucker had many other memories of “interesting” incidents on his missions. He recalled that the crews always felt relief when they reached the target and delivered their bomb load. On one mission, a 500-pound bomb failed to release from the top rack of the bomb-bay. Dunigan intended to drop it when they were over the Adriatic, but a substitute bombardier that was aboard for the mission, advised Dunigan that it would be safe to land with the bomb. The bombardier said that he had locked in the bomb and removed the fuzes. Although Dunigan questioned the recommendation, the bombardier assured him it was safe.

As the aircraft’s wheels touched down there was a loud bang. The bomb fell from the top rack, sprung the bomb-bay door open, hit the ground, bounced up, and dented the underside of the aircraft. Nearby ground crews scattered as the bomb rolled across the runway and into a field. It was unclear as to what happened to the bombardier, but he never flew with Tucker’s crew again.

Another time, after a bomb run, the radio operator reported that they had a 100-or-200-pound general-purpose bomb hung up. Dwight, the flight engineer, announced that he would take care of it. He disconnected from the oxygen system and grabbed a “walk-around” oxygen bottle along with a pair of pliers and headed back into the bomb bay. There, he eased down and placed one foot on the 18-inch wide catwalk that ran the center length of the bomb bay and the other foot against the side of the plane.

He wasn’t wearing a parachute because the chest pack would have been in the way. With the bomb-bay doors open, there was nothing but five miles of air beneath him. He cut the wires that held the bomb, allowing it to fall away from the plane. For his action, Dwight received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

On another mission, the aircraft began to lag behind the formation as they were headed for the target. Dunigan directed that a bomb be dropped to lighten the plane’s load, allowing it to maintain position with the group. But when it began to lose power again, Dunigan decided that they needed to lighten their load further.

He directed McQuistion, the bombardier, to drop another of their 500-pound bombs. Mac identified a spot in a patch of forest, away from populated areas he thought would be a safe place to drop the bomb. But the bomb set off a huge explosion, possibly hitting hidden oil-storage tanks. Black smoke rose to nearly 20,000 feet.

Tucker recalled another incident of the aircraft lagging behind the squadron and having to drop some of their bombs in order to lighten their load. They were almost to the target when they began to lose power. Dunigan ordered Mac to drop the first bomb, allowing them to make up ground. But then, after a few minutes, they began to fall behind again. Dunigan ordered another bomb to be released, then another, and another.

In the meantime, the rest of the group completed the bomb run and made the turn for home. The leader of the fighter escorts radioed Dunigan and told him to turn around and join the returning group because there weren’t enough fighters to protect the lone bomber.

But Dunigan declined and continued on. They were quickly over the target and dropped their two remaining 500-pound bombs. Dunigan may have also realized that if they didn’t reach the target, the mission wouldn’t be credited to their count.

On one mission, the co-pilot Garrison was sick and a substitute came aboard—an inexperienced, rookie lieutenant. Passing over the Alps, the aircraft experienced an oxygen leak. Dunigan and Dwight assessed the situation and determined that the leak was minor and decided to continue on. The rookie lieutenant disagreed and wanted to turn back.

Later, as they approached the target, the heavy flak was too much for the rookie. He began begging Dunigan to turn back and began crying about his wife and two kids he wanted to see again. Dunigan chewed him out and was able to calm him down. Dwight later told some of the crew that he had his hand on a fire extinguisher and that if the lieutenant had not calmed down he was “gonna bean him.” The rookie lieutenant never flew with the crew again.

Lieutenant Nisula was recognized for his excellent navigator skills and was often requested by the group-lead pilots. On one mission, with Nisula again the navigator of the lead ship, Dunigan and Garrison witnessed Nisula’s aircraft take a hit. They counted just seven chutes from the plane. Tucker’s crew was upset when they were informed that Nisula was reported as missing in action.

One morning in March 1945, operations informed the crews that that day’s target was Berlin. The distance to the target made the crews nervous. Fuel tanks were filled to the top and ammunition loads reduced by half to reduce aircraft weight. The mission to Berlin recorded the longest flight time for Tucker’s crew: nine hours and 20 minutes.

Some of the worst flak that Tucker witnessed was over Innsbruck, Austria, near the northern end of the Brenner Pass. The target for the day was a railroad yard. As they flew over the pass, they noted that the anti-aircraft guns had been placed high on the mountainsides—so close that the air crews could see the muzzle flashes. The aircraft were exposed for some 32 minutes of flak. Tucker believed that it was the longest time they were under fire by anti-aircraft guns.

Tucker experienced five strikes on Vienna. During one, the aircraft of the Fifteenth Air Force flew a “squadrons in trail” maneuver as one squadron followed another in a long column, dropping their bombs on a railroad marshaling yard. As a result, the city experienced a raid that lasted over two-and-a-half hours.

On a raid that targeted marshaling yards at Landshut, Germany, the area was without air defenses, allowing the bombers to approach at just 13,000 feet. As the lead ship released its bombs, the lead pilot radioed the rest of the group to hold their bomb loads; but the message was received too late. The lead reported that there were Red Cross emblems on the top of many of the railcars in the yard. At that moment, one of the trains blew up followed by several large explosions—the Germans apparently having the cars marked with Red Crosses loaded with ammunition.

Of Tucker’s 35 missions, 13 targeted oil refineries such as Blechammer and Ruhland, Germany, Brux in northern Czechoslovakia, and Moosbierbaum, Austria.

For Tucker’s last mission, to northern Italy, on April 23, he was assigned to a very green crew.

Given concerns about an individual’s last mission, it was customary to assign tail and ball-turret gunners to a waist-gun position so that there was someone to keep an eye on them. Tucker was quite nervous. While he took the left-waist position, the right-waist was manned by a rookie gunner.

As the bomber flew toward the target, Tucker saw that the rookie gunner was seated on a box with his head against the side of the plane. He had on his oxygen mask and appeared to be asleep. Tucker kicked the box and grabbed the rookie, stood him up, then chewed him out about the dangers of falling asleep on oxygen (an on-demand system that could cut-off or reduce the flow of oxygen when an individual was asleep).

Then Tucker noticed that the rookie’s gun was not loaded—the ammunition belt was not across the feed. Tucker really tore into him.

Then Tucker realized that the pilot seemed inexperienced, as he was incapable of holding his position in the formation as the aircraft kept drifting. They were in the low group and Tucker soon noticed that their left wing was directly under the bomb-bay doors of the plane above them.

Tucker called the pilot and informed him of his concern. But the pilot put him off, telling him that it was just a case of nerves. Tucker shot back that he had flown enough missions to know that bombs had been known to fall out of a bomb bay and hit the aircraft below. Though the pilot continued to seem unconcerned, he did move out from under the other bomber.

Tucker completed his service as a staff sergeant. Returning home, he was discharged and went to work as a fisherman. But he eventually decided to go back into the Air Force and stayed until retiring in 1967 as a master sergeant.

Later, Tucker’s thoughts were drawn to those who didn’t make it home: “About all of those who were left behind were young men who would never return home to start a new life. I thought about the potential that lay buried in graves so far away; young men, in the prime of life . . . I decided that somehow I had to honor them; and the only way I could think of to do that was to get on with my life”—a thought that so many other veterans likely had as well.

Frequent contributor Allyn Vannoy lives in Hillsboro, Oregon, near Portland.

I really enjoyed this, as I’ve been binge watching that old 60’s TV series “Twelve O’Clock High” on Amazon Video for the past several weeks too.

A good read about a service that suffered some of the worst casualties of WWII and had courage and resilience by the ton. I thank them for their service to our great country!

Great story. Thanks!