Photo Essay by Kevin M. Hymel

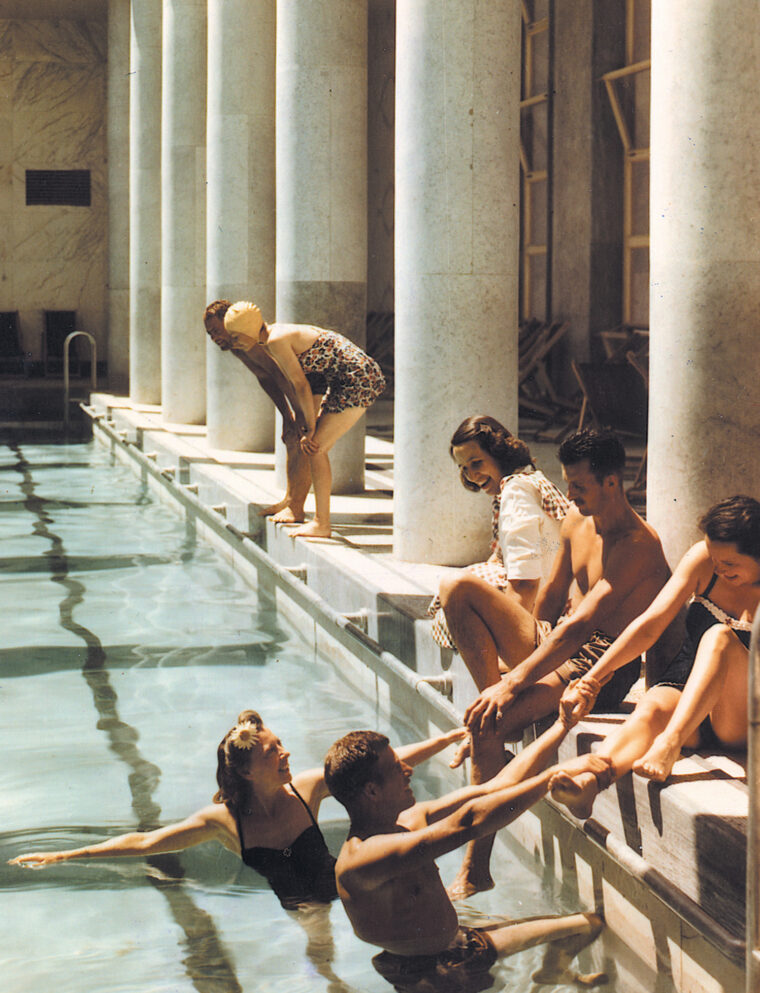

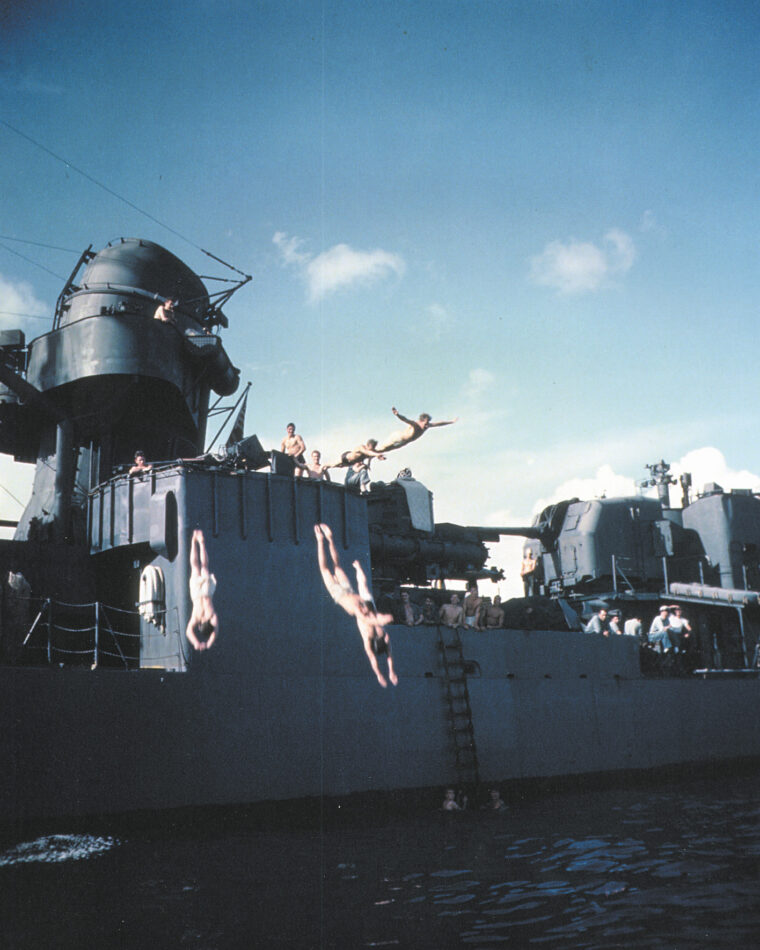

For the lucky few that got the opportunity, putting on a bathing suit and hitting the waves or pools was a welcome escape from the war. Both men and women of the U.S. military took advantage of every opportunity to get wet, from elaborate swimming pools operated by the Red Cross to simple streams discovered by a patrol or squad. It was relaxing, a reminder of home and a break from the rigors of war.

The greatest challenge for anyone lucky enough to locate a standing body of water was finding a bathing suit. For men, some government-issue trunks found their way to the front. They were black, made of cotton, with a drawstring in the waist and a slanted pocket on the right side. They were shipped out in wooden boxes, 240 pairs to a box.

For women, the task was a bit more difficult. They relied often on sympathetic civilians and ingenuity. Some women in the South Pacific fashioned suits out of parachute silk. Women’s suits also went through a radical update during the war. The one-piece became a modest two-piece, liberating women’s midriffs from the tyranny of the cover-up to save fabric for the war effort. In fact, women’s suits were referred to as bathing suits until 1946 when the name was replaced with “swimsuit” for the Miss America Pageant.

When trunks and silk were not available, soldiers improvised the only way they knew how. They went skinny-dipping. With women so scarce at the battlefront or the sleepy, boring outposts that had to be manned, most men shed every stitch of their uniforms to get wet. Certain male only hotels in Paris permitted “birthday suit” swimming, while men on occupation duty in isolated areas such as Bavaria took to the local rivers sans skivvies. Women were less inclined to risk the same exposure, but isolated lagoons could provide similar security.

Anywhere in the world, wherever American troops set foot and the climate was comfortable, one thing was sure. Someone was bound to break ranks and head for the water, if only to forget about the war for a little while.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments