By Kevin Seabrooke

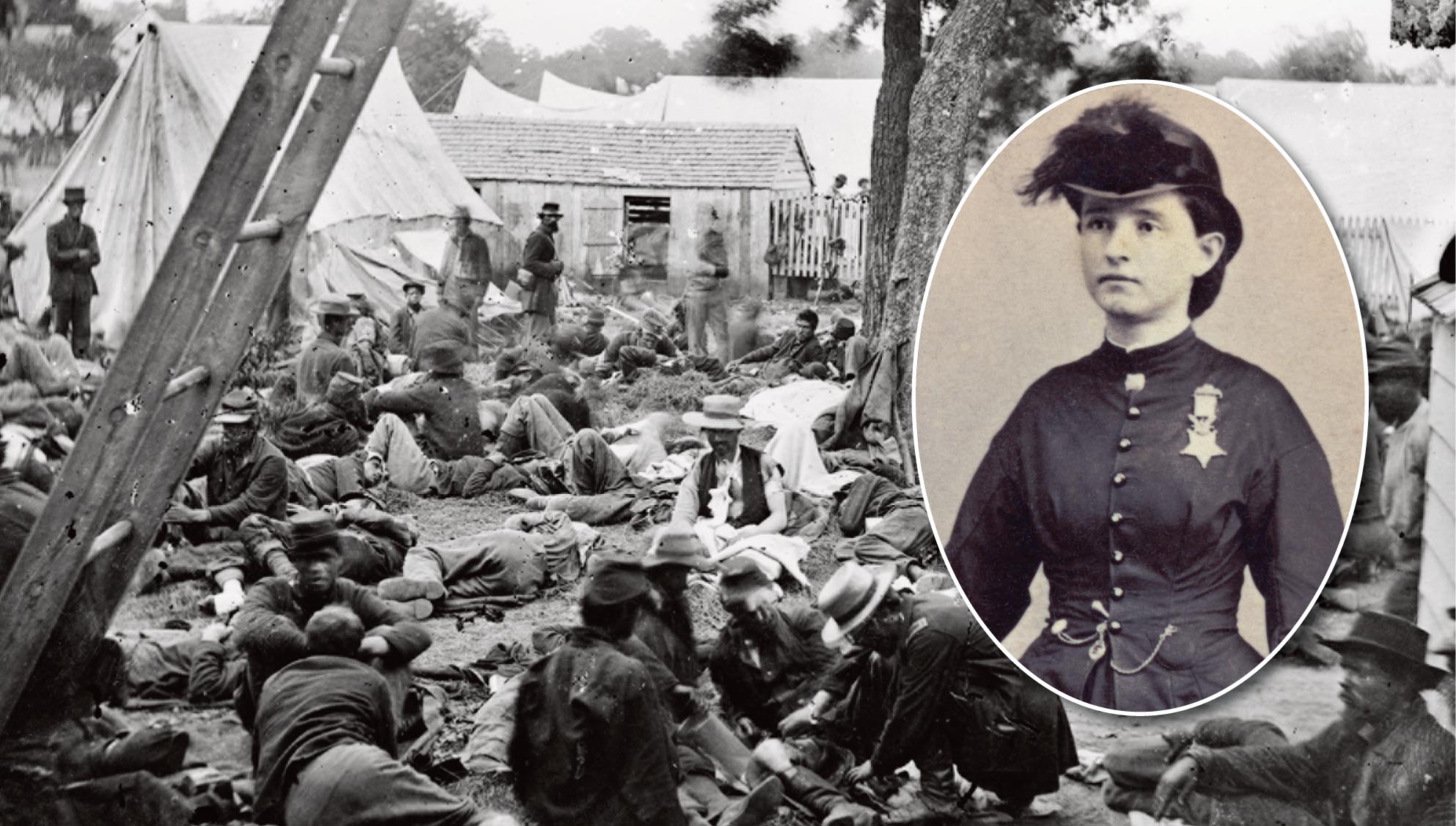

Born to progressive parents in Oswego, New York, Mary Edwards Walker and her six siblings were raised as “Free Thinkers” and taught to question everything. A non-conformist, Walker objected to traditional women’s clothing, arguing they were uncomfortable, inhibited mobility, and spread dust and dirt. She would wear trousers and jackets—her Medal of Honor pinned to it—throughout most of her life.

Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College in 1855 and went into private practice in Rome, New York, with a fellow medical student, Albert Miller, whom she married. But the practice failed and they later divorced.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Dr. Walker tried to join the U.S. Army as a surgeon, but wasn’t accepted because she was a woman. She was offered a position as a nurse, but wouldn’t take it. She volunteered to serve with the Union Army at the First Battle of Manassas, assisting in a field hospital.

Dr. Walker then volunteered at the temporary hospital set up at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C., and organized the Women’s Relief Organization to help the families of the wounded. During 1862, she moved through Virginia, treating the wounded as an unpaid field surgeon near the front lines at Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

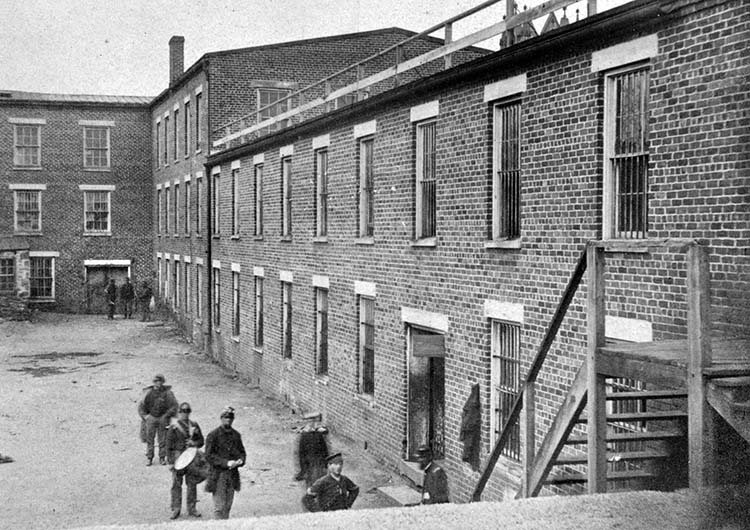

In 1863, she received a commission in Tennessee as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (civilian)” from the Army of the Cumberland, serving with the 52nd Ohio Infantry. She reportedly often crossed the lines to treat civilians, but on April 12, 1864, while assisting a Confederate surgeon with an amputation, Confederate troops detained her as a spy. She spent four months in Castle Thunder, a former tobacco warehouse in Richmond, Virginia, used by the Confederacy for civilian prisoners accused of spying or treason.

After she was freed in a prisoner exchange, Dr. Walker served at the Louisville Women’s Prison Hospital and at an orphan asylum in Clarksville, Tennessee.

On November 11, 1865, President Andrew Johnson presented Dr. Walker with the Medal of Honor on the recommendation of Major Generals William T. Sherman and George H. Thomas. She is the only woman to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

“[Dr. Walker] has devoted herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the field and hospitals, to the detriment of her own health, and has also endured hardships as a prisoner of war four months in a Southern prison while acting as contract surgeon,” Johnson said in his citation. “Whereas by reason of her not being a commissioned officer in the military service, a brevet or honorary rank cannot, under existing laws, be conferred upon her; and Whereas in the opinion of the President an honorable recognition of her services and sufferings should be made.”

In 1916, after a Congressional request for a review of Medal of Honor recipients, 911 were rescinded, including Dr. Walker’s. She refused to give it back and continued to wear it until her death in 1919. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter reinstated the award.

After the war, Dr. Walker received a disability pension for muscular atrophy that she suffered while in prison in Richmond. She spent the remainder of her life advancing the cause of women’s rights.

In 2024, Dr. Walker will be honored as part of the American Women Quarters Program.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments