By Robert Swain

Flanking movements were long known to English military commanders, but traditionally they were limited to maneuvers by one wing around an enemy’s line—not by the entire army itself, which would have been considered highly unorthodox and far too risky. At least that was the thinking in the autumn of 1513, when the English had to deal with the

sudden appearance of James IV of Scotland, streaming across the border with an unprecedentedly large army of 40,000 men. What made the situation even more trying was that young King Henry VIII—James’s brother-in-law—was off pursuing glory in France with the cream of England’s fighting men, leaving the country’s defense in the hands of a 69-year-old general whose family name was still under a pall from its misbegotten participation in the War of the Roses three decades earlier.

The perceived wisdom of what a successful flanking maneuver could accomplish would change radically that September when the English realized with alarm that the Scots were deadly serious about honoring their “Auld Alliance” with France. Responding to a piteous entreaty from Queen Anne of Brittany to help her resist “the daring insolence of a royal outlaw”—Henry VIII—James had first ordered a raid-in-force in mid-August to distract Henry from his marauding agenda in France, but this chivalrous initiative won James only seven burned villages in Northumberland before an English force in the area fell on the Scots, inflicting several hundred casualties and taking an additional 300 prisoners. This reversal was sufficient to cause the Scots to withdraw from the scene, and the debacle quickly became known as the “Ill Raid” on both sides of the border.

Undeterred, James raised an even larger army at Edinburgh and again crossed into England at Coldstream on August 22. Accompanying his army of 40,000 Scotsmen was a contingent of 5,000 French troops under the command of the Comte d’Aussi, whose ranks included a number of military advisers whose mission was to teach the Scots how to employ the formidable 18-foot-long Swiss pikes that were all the rage in Europe at the time. Augmenting James’s armament were 17 pieces of artillery, including seven enormous brass cannon called the Seven Sisters that required a team of 36 oxen each to pull.

The Scottish army, the flower of its country’s feudal chivalry, was characteristically pugnacious, although somewhat unsettled by persistent rumors of ill omens hanging over the campaign. It was widely reported that a mysterious, gray-haired old man at St. Michael’s Church in Linlithgow had warned the king personally not to venture into England, and that a disembodied voice at Mercat Cross in Edinburgh had been calling thousands of men by name to prepare to meet their doom in 40 days. Such omens were taken seriously by the superstitious Scots, but they valued their own courage and reputations too much to turn back.

While James was heading south, hounded by phantoms, Thomas Howard, the elderly Earl of Surrey, was being alerted by spies to the troubling new incursion. Widely regarded as a national hero in England for his numerous campaigns against the always bothersome Scots, Surrey was staying at Pontefract Castle in west Yorkshire. Still angry about being left behind to defend the realm while the king was off chasing martial glory in France, Surrey mustered what troops he could locally and ordered his son, 40-year-old Thomas Howard II, now serving as Henry’s lord admiral, to ship his remaining artillery to Newcastle, roughly 100 miles south of Edinburgh on the coast.

When the presence of well-armed Scottish troops in northern England was confirmed, Surrey sent an urgent appeal to the York city council to authorize the immediate muster of more militia. Meanwhile, he prepared to move north and take command personally. James, for his part, was surprised to learn that Surrey was making such a determined show of energy, believing him too old for active campaigning. But others in the Scottish camp, well aware of Surrey’s long-proven combativeness, were increasingly apprehensive. While James dallied at Castle Ford with Lady Heron, wife of the castle’s absent lord, his rain-soaked nobles in the field grumbled unhappily among themselves.

Upholding his reputation for unflinching defense of England’s border, Surrey came steadily north, gaining an additional 20,000 men through forced levies along the way. After resting briefly in Durham, he led his troops 16 miles farther north to Newcastle, where the royal artillery was waiting as ordered, brought ashore by his son along with 1,200 marines from the royal fleet. Despite the comforting arrival of reinforcements, Surrey’s situation remained tenuous at best. His army was easily outnumbered by James’s force and ill supplied with food in a barren area that seldom produced a surplus harvest. Besides, as James suspected, Surrey was beginning to feel his age, and a flare-up of rheumatism made it difficult for him to move about. Accordingly, he kept to his coach, earning him the scornful description, “an old crooked earl in a chariot.”

Howard’s presence at his father’s side prompted Surrey to convene a parley of his officers and announce that his son would serve as his second-in-command. Surrey’s staff, like all of England, was well aware of the lord admiral’s naval heroics two years earlier, when he had captured King James’s flagship and killed his Scottish counterpart. They found his new appointment entirely agreeable. Turning their attention to supplies, a hurried check revealed that the English had just enough beer left for two more days and sufficient food for four. This prompted Howard to argue that it was imperative to goad James into battle immediately, no matter how outnumbered they were at the moment. An army might be able to fight without food, but an army without beer was another matter altogether. For the time being, no decision was made about what to do next—except to march on and be guided by events.

Surrey, like his son, was worried that they might exhaust their foodstuffs or that James might withdraw across the border. Agitated by continuing rumors of the latter, Surrey reconvened his war council with an air of urgency. Some in the group recommended a strategic retreat to reestablish their supply lines, but Howard disagreed and insisted that they move even closer to James’s position, now only six miles away. Spoiling for a fight, Howard wanted more than anything to tempt James and his ever-aggressive Scots into combat. Despite resistance from several nobles who considered this a foolhardy course of action, Surrey ended the debate by agreeing with his son. Recalling James’s chivalrous nature from personal contact with the king 10 years earlier, Surrey decided to send a direct challenge. In a hand-delivered note he offered to give battle no later than Friday, September 9, three days hence, between noon and 3 pm, and he politely requested James “to tarry for the same.”

The Howards, father and son, hoped that James would consider himself honor-bound to fight his challenging opponent. This was what chivalrous knights were supposed to do, but at first James did not take the bait. Instead, annoyed by Surrey’s impertinent challenge, he replied disdainfully, “Who is a mere earl to set terms for a king?” He continued moving westward to take an exceptionally strong position on a 500-foot-high, mile-long hill named Flodden Edge, near the River Till. There he would have a marsh on his left and a steep slope on his right. With little choice, Surrey moved his army closer to James’s position, not realizing that the Scots had greatly strengthened it with the addition of a manmade parapet and a newly dug ditch.

Coming into view of the Scots on the high ground just to the north, the Howards were shaken to see that the only passable approach to James’s position ran straight up the middle of the now heavily defended hill. As the Surreys realized at a glance, such an advance would mean braving the fire of well-placed artillery and archers shooting down at them from higher ground—a near-suicidal prospect at best.

Determined not to leave matters as they were, Surrey made another appeal to James’s chivalrous nature, suggesting somewhat disingenuously that the Scots relocate to more equitable ground. He justified the ridiculous request by reminding James that his original offer of battle implied meeting on “a fair field.” But James frustrated Surrey once again by refusing even to see the herald who brought the message. Surrey’s pledge to fight on September 9 still stood, but he had failed to effect a change in the Scottish position. The only satisfaction he could derive from his letter-writing ploys was the knowledge that the Scots were still in England—they had not withdrawn across the border as he had feared.

Surrey called another council of war to review his options. Before much could be said, Howard forestalled further discussion by bringing up a daring and heretofore untried idea: marching the entire army (sans heavy baggage) around the eastern flank of James’s position and launching an attack from the rear. The council sat still, hearts in their mouths, while Howard argued in favor of his idea. James, he said, would not understand the maneuver and likely would do nothing in response. The rear of the Scottish position could hardly be stronger than the one they already faced, and by inserting themselves between James and the border the English would be well placed to cut off the retreating Scots. Surrey chimed in that his charter from Henry precluded him from entering Scotland without permission—another argument in favor of fighting the enemy where they stood.

The undecided nobles in the council eventually came to appreciate Howard’s idea, forgetting for the moment their ever-present hunger and the damp, bone-chilling September weather. Finally, with Surrey’s blessing, a decision was reached: Howard would lead the army around the Scottish position, an eight-mile forced march in the face of the enemy. That decided, the jittery council members departed to supervise their men in finding shelter for the night and foraging, for any available edibles. Afterward, they would attempt to get some sleep themselves, for tomorrow they would undertake Lord Thomas’s daring strategy, and either be victorious or die trying.

At first light on the September 8, Surrey gave orders for the army to prepare for its march around the Scots, with Howard leading the army into its new position, hopefully without any inconvenient interference from the Scots. To further complicate matters, a lashing rain began within the hour and drenched the miserable men, soaking their pitiful loaves of bread—all they had to eat. After proceeding for three grueling miles, Howard called a halt while he and several officers ventured ahead to assess the Scottish position. Howard hoped to discern a more favorable approach from the east, which would prevent them from having to completely encircle the Scots. But the marsh protecting the Scottish flank was more extensive than first realized, ruling out that possibility. Returning to his troops, Howard ordered them to resume the difficult and risky maneuver of encirclement. For the time being, at least, the rain and mist were of some help in serving to mask their northeasterly movements.

More grim-faced than usual, Howard lent all his formidable command skills to the twin tasks of getting the men to advance and maintaining order under such foul conditions. The footing was treacherous as the men struggled along through the low-lying fields, wet to the skin and suffering with every step, but Howard knew how to challenge and inspire them by demonstrating a willingness to match their efforts personally, mile for mile. With everyone nearly exhausted, the lord admiral finally ordered a halt early that afternoon.

By now the Scots were well aware of the enemy’s movements, but they were puzzled by what appeared to be the English decision to move toward Berwick, 11 miles away on the coast. As a consequence of this erroneous conclusion, James did nothing—precisely as Howard had predicted. The Earl of Angus, one of the king’s most trusted advisers, urged James to open fire on the English, only to be told to go home if he was so afraid. The earl, in tears, took his leave, protesting that his past service should have inoculated him against such unfair royal criticism. James’s master gunner, Borthwick, fell to his knees, begging to be allowed to fire on the English in their exposed state. Still the courtly James refrained, and the English were allowed to move around his army unmolested.

Just before dusk, Surrey retook command of the army from his son and promptly called another war council. While the English commanders were assembling, James sent a stunning message that he would accept Surrey’s previous offer of battle on the 9th. Surrey and the others were astounded but delighted—no one could explain fully why James changed his mind. Perhaps, like Surrey, he feared that his army would miss the chance to fight if the enemy withdrew. Or perhaps he worried that his volunteer army was slipping away and that he was losing his manpower advantage. With the looming expiration of the soldiers’ pledge to bear arms for exactly 40 days, he would have to fight now or not at all. If anyone remembered the disembodied warning at Mercat Cross, they were good enough—or frightened enough—to keep it to themselves.

Excited by the prospect of doing battle, particularly after another miserable night of cold rain, the English were up at first light, although scarcely ready to fulfill their own promise to fight. A lighter rain continued as Surrey told his son to proceed with his plan for deployment. However, the sloppiness of the marshland underfoot so slowed their progress that it took Howard six hours to move the army across a bridge over the River Till and take up the position he and his father wanted it to occupy. Seeing the English move at will through the mist and rain, James at last ordered his men to set fire to the refuse in the Scottish camp so that the prevailing wind might blow the smoke into the faces of the enemy. Fitfully, the refuse started to burn, but the resulting smoke served merely to annoy the English while effectively camouflaging their changing position.

When the smoky haze finally cleared, the English vanguard was within a quarter of a mile of Branxton Hill, two miles north of the Scottish position on Flodden Edge. Alarmed, James ordered his already well-placed army to move forward and occupy Branxton Hill before Surrey could do so. To Surrey’s surprise, he could now see that the two armies were roughly equal in size, and he quickly realized that James’s numerical superiority had been eroding daily due to the independent-mindedness of the Scottish clans.

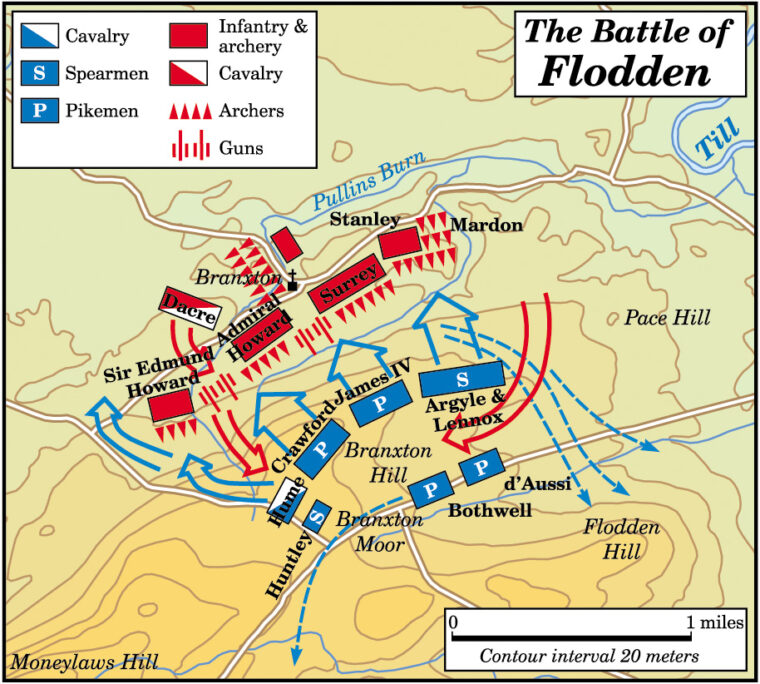

As James was resituating his men and artillery on Branxton Hill, so too were Surrey and his son making their final preparations to fight. Once again the English benefitted from James’s exaggerated sense of chivalry, which left him duty-bound not to take advantage of his opponents’ exposed position. Surrey, who had come forward to join his son, was able to recompose the English ranks without undue haste. The relatively inexperienced Cheshire troops under his younger son Edmund took up position on the English right, while the vanguard under Howard and Sir Marmaduke Constable occupied the center and other more experienced troops filled in beside them. The remaining infantry, still arriving across the bridge, formed the English left, with two reserves of light cavalry moving into position behind the front ranks. All this maneuvering took several hours, and an attack by the Scots at any point might well have destroyed Surrey’s army piece by piece. Such an attack never came.

It had been particularly difficult for the English to muscle their artillery pieces into place, punctuated by sounds of men and horses straining to their tasks on the increasingly crowded front. Tempers flared and curses flew among the teamsters, but everything was more or less in place by early afternoon, to the slightly contemptuous amusement of the Scots, who removed their own boots and danced about in their hose to indicate their firm intention to stay where they were. Within half an hour, a booming artillery duel initiated the battle. Almost immediately the English gunners managed to demonstrate their technical superiority, which abruptly ended any amusement for the Scots.

Stung by the deadly accurate English cannon fire, the Borderer clansmen on the Scottish left, accustomed to their namesake raids, quit their positions on higher ground and raced impetuously down the slope, propelling themselves against the English right. The Cheshire line quickly broke into disorganized flight. The boiling-mad Scots, too undisciplined to exploit their advantage, left off chasing the fleeing English to plunder and collect prisoners for ransom. Occupied by these self-serving pursuits, the men on the Scottish left did not see James’s center as it came down the hill behind them. It was a fatal oversight.

The second Scottish assault was raked in turn by Howard’s artillery, while his archers loosed deadly flights of arrows into the advancing enemy. The Scottish attack began to falter under these twin assaults, with many falling dead or wounded on the slippery slope. Meanwhile, English cavalry under Lord Dacre fell on the Scottish plunderers and dispersed them with considerable casualties. Howard, shaking off his weariness, shouted for his men in the center to renew their efforts. The muddy field began to turn blood-red under foot.

Positioned well above the tumult, James saw the abrupt change in fortune and ordered his right flank to join the attack. To meet this third assault, Surrey ordered his archers to loose another torrent of arrows into the descending Scots. Once again, English cannon fired at close range into the mob, and it was not long before the pressure from so many sides wore down James’s center. No quarter was asked and none was given. One by one, the Scottish Earls of Crawford, Montrose, Lennox, and Argyle fell dead on the battlefield, the latter two wearing only their tartans. Totally surrounded, James himself was mortally wounded, his neck torn “open to the middle” and several arrows imbedded in his body. His striking arm had almost been severed. Dazed survivors of this last savage exchange staggered off the field as dusk began to fall.

Surrey, not yet convinced that he had won the battle, withdrew a short distance in the fading light. Throughout the night, amid the moans and prayers of dying comrades, the Scots continued to slip away. In the morning, the English awoke to find a line of unmanned cannon facing them from Branxton Hill. In front of them was a corpse-littered field containing the bodies of thousands of Scottish and English soldiers. James’s body was not among them, and for a time there were rumors that he had escaped and that a counterfeit “king” had been killed in his place. But when he failed to return to Edinburgh, his people had to face the appalling reality that their monarch and the entire flower of Scottish chivalry were dead.

Casualties from the relatively brief battle were appallingly high for the Scots, making this the greatest military disaster in their history. Slain alongside James IV and one of his sons were 12 earls, 14 lords, one archbishop, two bishops, two abbots, and the chiefs of the Campbell and MacLean clans. Knights and gentlemen from nearly every distinguished house in Scotland had perished, along with 10,000 less exalted but no less mourned foot soldiers. English losses numbered about 1,500 men-at-arms, mainly from the right flank, but few high-ranking noblemen.

The Battle of Flodden Edge (or more accurately, Branxton Hill) eliminated Scotland as a military threat to Henry VIII for years to come. As for the victorious Howards, Henry rewarded them handsomely the following year. Surrey was elevated to Duke of Norfolk (a title once held and lost by his father, along with his life, in defense of Richard III’s crown at Bosworth Field), while Howard was granted his father’s title of Earl of Surrey in gratitude for supplying the original idea that had turned a disadvantageous position into a brilliant victory. In 1524, he succeeded his father as Duke of Norfolk and went on to become one of Henry VIII’s principal generals and advisers. But never again

did the duke risk flanking an enemy force with his entire army, preferring to negotiate whenever he encountered unfavorable odds. Perhaps he realized that few opposing commanders would be as foolishly chivalrous as James IV had been that rainy September afternoon at Flodden Edge.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments