By Nathan N. Prefer

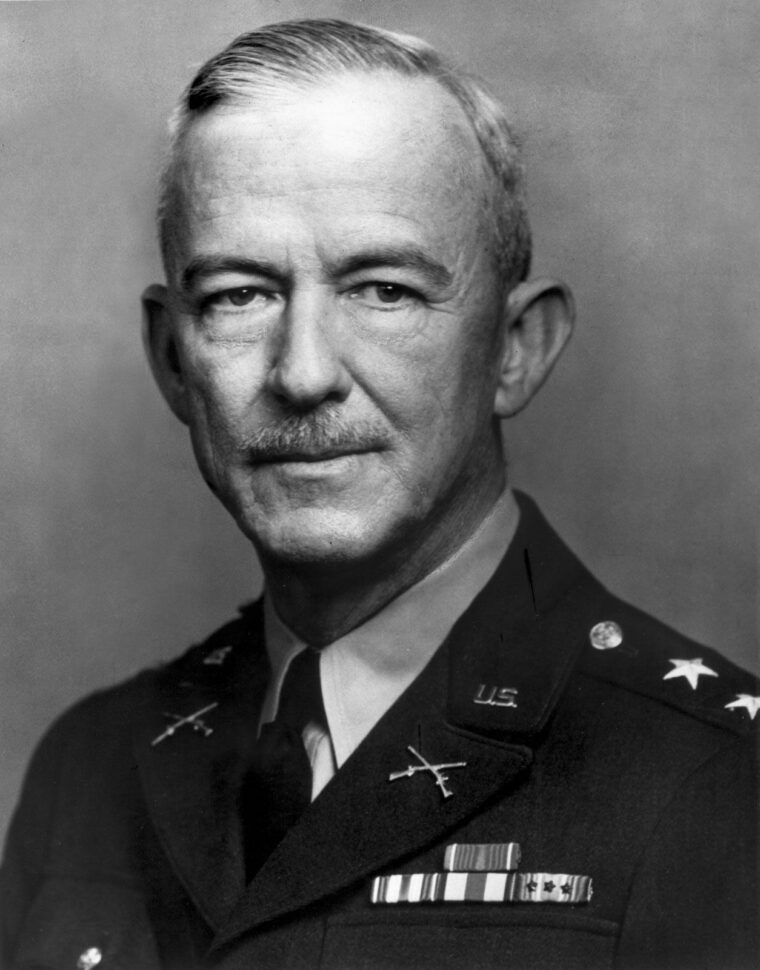

He was one of only two soldiers in the United States Army to rise from private to four-star general and to command one of the largest armies in America’s biggest conflict. Yet even during World War II, he was overshadowed by the more flamboyant leaders including General George S. Patton, General Omar N. Bradley and, of course, General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Even General Eisenhower would complain to the U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that General Courtney H. Hodges was not getting the “credit in the United States for his great work.”

Courtney Hicks Hodges was born on January 5, 1887, in Houston County, Georgia. The son of a local newspaper owner, he became a writer on his own, paying particular attention to proper English grammar. His childhood was filled with hunting trips, baseball games, fishing, and swimming. Enthralled by his neighbor’s tales of the famous Revolutionary War “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion, young Hodges was soon interested in becoming a soldier.

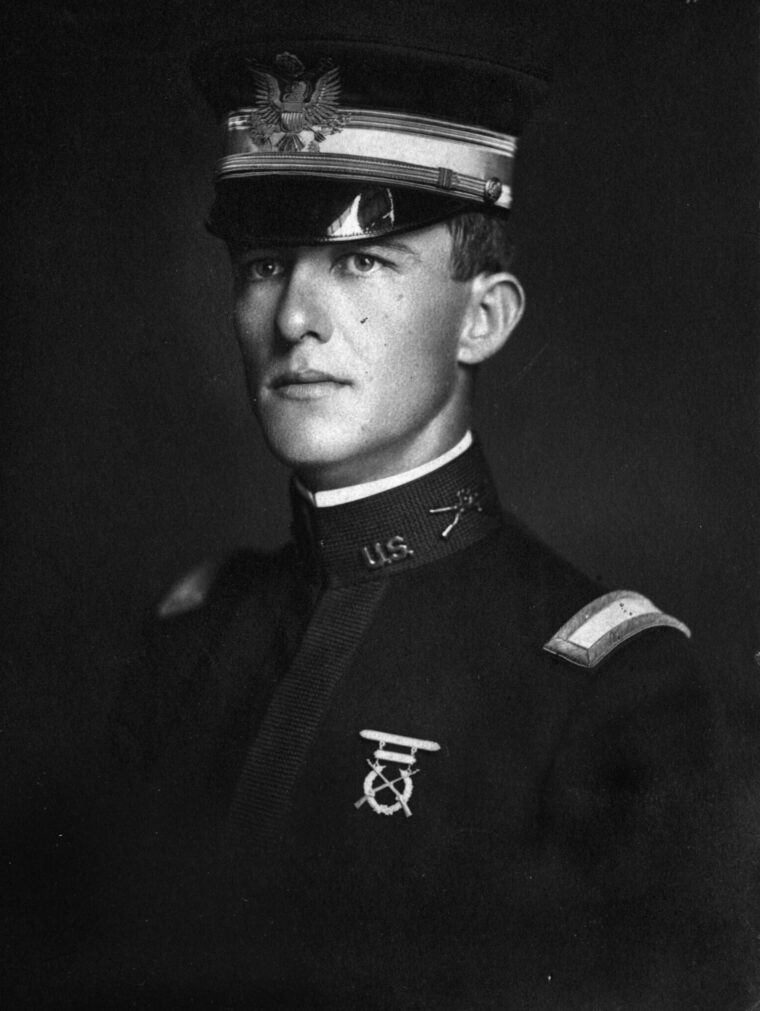

After graduating from Perry Public School in 1903, he enrolled in North Georgia Agricultural College. Here he became a bugler, joined a fraternity, and drilled with the college’s cadet group. Soon he received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, from his local congressional representative. There he found himself in some difficulties.

Exactly what Cadet Hodges’ difficulties were at West Point vary by account. Some family members believe it was the hazing which drove him from the academy, while others think he was covering for the misdeed of another cadet—which some believe was George S. Patton. Officially he was found “deficient” in mathematics and dropped from the academy.

Hodges left West Point and enlisted as a private on November 4, 1908. Almost immediately he distinguished himself as a marksman, winning several shooting medals and contests. At the National Marksmanship contest at Fort Niagara, New York, Private Hodges came in second place.

Hodges’ first overseas assignment was to the Philippines. That same year (1909), he received a commission as a 2nd lieutenant. He made the acquaintance of fellow lieutenants George C. Marshall and Henry H. “Hap” Arnold.

Hodges’ unit, the 13th Infantry Regiment, was rotated back to the United States. There he was transferred to the 6th Infantry Regiment at El Paso, Texas, and applied for the Army’s Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He was turned down because of poor hearing. But Hodges had other successes, winning the Florida State Rifle Competition with a perfect score.

Then came the Mexican Punitive Expedition, and Hodges was soon hunting Mexican bandits with Lieutenant George S. Patton and future Ninth U.S. Army commander, Lieutenant William H. Simpson. Other than rescuing a downed aviator and commanding a machine gun company, then an infantry company, the expedition was uneventful for Hodges. He did pass the examination for 1st lieutenant and soon after was promoted to Captain.

With the outbreak of war in Europe, the 6th Infantry Regiment was transferred to Georgia, where Captain Hodges earned rapid promotion to company and battalion commander. By 1917, he was a temporary lieutenant colonel commanding the 2nd Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, 10th Infantry Brigade, 5th Infantry Division. It was in this assignment that he went overseas to France and fought in the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives, earning a Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, and Bronze Star.

During the battle for the town of Brieulles, France, on November 2-4, 1918, Hodges earned his Distinguished Service Cross. He went forward to find the best place for his command to cross the Meuse River. On finding one, he organized a storming party and attacked the Germans not 100 yards from the crossing site. Hodges fought for over 20 hours to gain the bridgehead and get his command across and up the heights east of the river.

With the armistice, the 6th Infantry Regiment was assigned to garrison Trier, a German city of 50,000 inhabitants. Hodges enjoyed the sights, food and people while reviewing the tactical performance of his battalion over the last several months. He also indulged in his favorite pastime, shooting. He won a medal for winning a rifle match while in France and was on the Army team for the Inter-Allied Competitions held in Le Mans, France, in June 1919. The next month the 6th Infantry Regiment was returned to the United States under the command of temporary Colonel Hodges.

After several months in Georgia, Hodges was ordered to the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In Washington, meanwhile, Congress was busy reducing the Army to a bare minimum and reducing most temporarily promoted officers to their permanent ranks. But during this post-war period a World War I hero, General Douglas MacArthur, was appointed Superintendent of West Point. Coming back to his former academy, MacArthur was determined to remake the academy. He brought in new and generally younger instructors. One of these was Courtney Hodges.

Hodges’ next posting was to the prestigious Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He graduated in 1925, number 94 of 258. From Kansas, Hodges was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, to teach tactics at the Army Infantry School. There he renewed his acquaintance with Bradley and met future generals Matthew B. Ridgeway and Mark Clark.

With the permanent rank of major, Hodges was next sent to Langley Field, Virginia, on loan from the Infantry School, where he taught at the Air Corps Tactical School. Over three years, he logged more than 250 hours flying. He developed his appreciation for air power while he worked at Langley. During his time at Langley, he met the widow of an Air Corps officer, Mildred Lee Buchner of Montgomery, Alabama. The two got along well, and after she had shot her first bullseye on the target range Courtney asked her to marry him. They remained together for the next 35 years.

In August 1929, the Hodges were transferred to Fort Douglas, Utah, but their stay was brief. Before leaving Langley, Major Hodges had again met Lieutenant Colonel Marshall and had said that he would like to return to Fort Benning. The call to return to Fort Benning came in November. He was assigned as an instructor under Colonel Joseph W. “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell. He served on the Infantry Board, whose job was to come up with new and improved weapons. In this capacity Hodges was instrumental in adapting the new M-1 Garand semi-automatic rifle, the new standard helmet, the Jeep, and improved combat rations. He also developed a two-week course for National Guard general officers.

The next move was to Washington, D.C., and a year at the Army War College where he studied strategic planning for the western Pacific. Graduating in June 1934, he was sent to Vancouver Barracks in Washington State as lieutenant colonel and executive officer of the 5th Infantry Brigade.

Then came another summons, this time to the Philippines, where Hodges trained the fledgling Philippine Army. As operations officer, Hodges organized the famous Philippine Scouts. He also first worked alongside Lieutenant Colonel Dwight Eisenhower, also on MacArthur’s staff at this time. Like Eisenhower, Hodges did not care for MacArthur, but did their best.

By 1938, General Marshall had become the Assistant Chief of Staff, War Plans Division. He asked Hodges if he would like to return to work with the Illinois National Guard. But world events were moving so fast that the transfer was to Fort Benning, not Illinois. The Hodges’ returned to Georgia in August 1938, where Courtney was appointed assistant commandant of the Infantry School. After 19 months, he was promoted to full colonel and made the commandant of the Infantry School. He was promoted to brigadier general in May 1940.

In May 1941, Hodges was promoted to major general and appointed Chief of Infantry. Bradley took command of the Infantry School. Hodges saw the implementation of many ideas he had championed while on the Infantry Board. Hodges made repeated inspections of the massive maneuvers in Louisiana, Texas, and the Carolinas.

Hodges also oversaw the re-arming of the Army. Everything from the new anti-tank rocket launcher (bazooka) to the bayonet had to be redesigned and tested. He was particularly proud of the work he did developing the Jeep. Hodges was also personally involved in the development of the new 6X6 truck.

Three months after Pearl Harbor, the posts of branch chiefs were abolished. Hodges then became the commander of all 10 of the army’s replacement centers. Once again, his good work earned Hodges promotion to lieutenant general and command of X Corps. But already Hodges was getting impatient for a combat command, opining that he would have loved to take the Third Army to the Far East.

But there were problems while he held this command. The army at the time was segregated, and some units of African Americans had been assigned to his area. This caused friction with both white soldiers and local citizens. Several incidents arose, including the killing of one African American soldier by a Mississippi sheriff, but Hodges worked tirelessly to alleviate the friction.

Marshall then sent Hodges to inspect the fighting fronts in North Africa and Italy. During this trip Hodges went up to the front lines, spending nights at a regimental command post under artillery fire. Then it was back to Third Army.

At the end of 1943, Third Army headquarters was being prepared to go overseas. Hodges looked forward to seeing combat.

Unknown to Hodges, Marshall believed that he would command the invasion of northern France and was preparing a list of generals to serve under him. He wanted Lieutenant General Lesley McNair to command an army group with generals Bradley and Jacob Devers commanding armies within that group. But McNair had a hearing problem, so Marshall revised his scenario to Devers commanding the army group while Bradley and Hodges commanded the armies under it.

Early in January, Third Army received orders to sail to England. But these orders did not include Hodges. Nor was he summoned to Washington for the usual talks before a major headquarters departed. Even more strange, he was not included in the shipping orders when the headquarters sailed. He stood outside as Third Army left for New York.

Instead, he was summoned to Washington and criticized for his selection of some senior staff officers in Third Army. Much later he learned that General Marshall had become so indispensable at the War Department that President Franklin D. Roosevelt forbade him to leave. This made Eisenhower the supreme commander of the cross-channel invasion and resulted in a wholesale shifting of senior officers.

Marshall wanted Hodges to command First U.S. Army, but Eisenhower preferred his friend Bradley. Eisenhower got his wish. Hodges learned that he had lost his beloved Third Army when a letter addressed to Patton as commander, Third Army, mistakenly arrived at his old Third Army headquarters. It was Hodges’ greatest disappointment since West Point.

At some point, Eisenhower would move up to senior command and Bradley would command an army group. There would be two, later three, subordinate armies. With Bradley leaving, Hodges would command First Army once Bradley moved up. In the interim, he would be its deputy commander.

Hodges appears to have gone ashore on D-Day at Omaha beach, although the record is unclear. He went ashore the following day and supervised the linkup of V Corps and VII Corps.

On June 11, Hodges was ashore again monitoring the attack toward Carentan when the group came under sniper fire. Hodges was frequently at the front trying to learn what was going on, the opposition’s strength, and what opportunities existed for advance. He acquired a Piper Cub artillery liaison plane and pilot, often flying over the front to gain better perspective.

By the end of July, First Army was stymied in the thick bocage country of Normandy. Bradley had developed Operation Cobra, intended to break out of Normandy. The plan required a massive bombing effort before the infantry and tanks were released to break through. Hodges was up front to observe the bombings, and when these fell short, was nearly killed. Several others, including McNair, were killed. Despite the tragedy, Cobra succeeded, and First Army renewed its advance.

As of July 27, Bradley delegated most of First Army’s operations to Hodges, allowing Bradley to take over Twelfth Army Group. On August 1, 1944, Hodges signed four pieces of paper, officially taking command of First Army.

Although he was supposed to command from his desk, Hodges often went into the field. He preferred to see things for himself.

A typical day at First Army headquarters usually began at 6:30 a.m. with the general and staff meeting. A review of two large maps was conducted, and Hodges listened quietly, interrupting to ask the occasional question. Hodges would turn to his operations officer, Brigadier General Truman C. Thorson, and say, “Tubby, let’s brew some medicine. Let’s just think this out loud.” And from these talks came the daily plan.

The French resistance uprising in Paris caused a problem for Hodges. He called in Gerow and put together a V Corps task force to rush to Paris and, despite disputes with French commanders, seize the French capital. When supplies began to run short and the Red Ball Express was proposed, Hodges came up with hundreds of trucks for First Army’s contribution to the supply highway. By September, the Allies approached the Siegfried Line, or Westwall, on the German frontier. First Army’s VII Corps first crossed the German border and attacked the Westwall.

Meanwhile, Hodges seized vital road junctions along the French-Belgian border, forcing the Germans to withdraw. At one point in September, First Army had troops in France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg.

By November 1944, First Army was pushing deeper into Germany. Hodges was directed to attack into the Huertgen Forest. Here developed one of the most enduring controversies involving Hodges. Despite fierce enemy resistance, he continued to push his exhausted units forward, ignoring opportunities to capture several dams which would have forced the Germans to withdraw. But it should be noted that Bradley, Hodges’ superior, later remarked, “To put it mildly, my plan to smash through to the Rhine and encircle the Ruhr had failed….”

First Army was fighting toward the Rhine when the Battle of the Bulge began. When the German offensive struck, senior Allied leaders were surprised. But Hodges was quick to realize that this was a serious threat, ordering countermeasures before noon on December 16. He requested troops from both the Ninth Army to his north and Third Army to the south. He sent the 101st Airborne Division to hold the vital crossroads town of Bastogne, a major factor in delaying the Germans.

To better coordinate operations, First Army was placed under Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. Despite suffering from influenza, Hodges led the defense and later counterattacks as ordered by the field marshal.

With the defeat of the Bulge counterattack, First Army went back on the offensive, overrunning the Huertgen Forest, capturing the dams, and moving to the Rhine. Hodges rushed troops across the Rhine bridgehead at Remagen established by the 9th Armored Division. Bradley sent more troops to First Army.

Once across the Rhine, First Army encircled the German industrial area, the Ruhr, from the south while the Ninth Army circled from the north. After the Ruhr was secured, the first American units, from First Army, reached the Elbe River. Eisenhower halted operations.

As the war in Europe ended, the war in the Pacific continued. Hodges was assigned “the big prize of leading all the ground units deploying from Europe to the Pacific.” He was highly recommended by both Marshall and Eisenhower and satisfied MacArthur.

First Army was assigned to the second of two major amphibious landings in Japan, Operation Coronet. This was set for the island of Honshu and the seizure of Tokyo. Under Hodges’ command would be the III (Marine) Amphibious Corps and the XXIV Corps for the initial landing, followed by additional troops from Europe after the beachhead had been established.

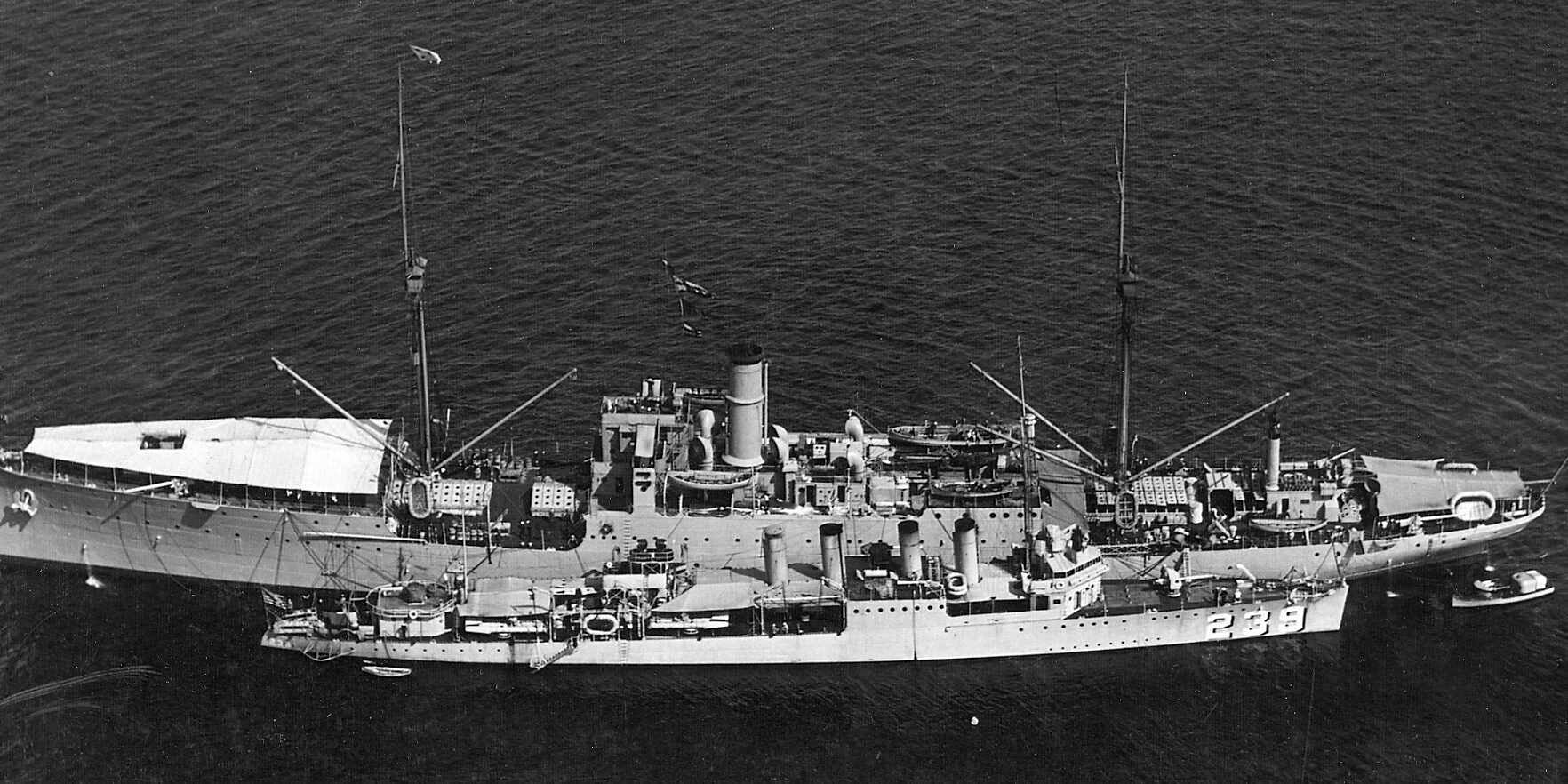

Hodges went home for a brief rest before arriving in the Pacific just as Japan surrendered. He was the only “European” commander present at the surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri in September 1945. Hodges was promoted full general in April 1945.

By March 1949, after 32 years, Hodges retired from the Army. He had acquired three Distinguished Service Crosses, three Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, and the Bronze Star among other recognition. Hodges died on January 16, 1966, age 79.

Bradley called him “a military technician whose faultless techniques and tactical knowledge made him one of the most skilled craftsmen of my entire command.” Others thought him remote, cautious, and uninspiring. Nevertheless, First Army was the workhorse of the “Great Crusade” and fought the hardest battles, sustained the highest casualties, and gained the most ground of any of Eisenhower’s field armies.

Nathan Prefer is the author of numerous books and articles on World War II. He received his Ph.D. in military history from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments