By James Marino

The third banzai charge that night struck the inexperienced, worn out infantry with the force of a blowtorch. Possession of the airstrip on this malaria-infested, tropical island in the South Pacific in August 1942 would determine the fate of Australia and Allied fortunes in the Pacific.

Japanese soldiers had yet to fail, let alone retreat, since Pearl Harbor. The veterans of Malaya, the Philippines, and the East Indies stormed forward, confident of victory. Machine guns hammered at the Japanese as the young soldiers clung to their defensive positions near the airstrip. The world, as well as General Douglas MacArthur, wondered if these Australians could stem the Japanese tide. The Diggers held. Raw Australian militia and seasoned regulars defeated the Japanese at Milne Bay and changed the course of the war in New Guinea and the South Pacific. General Viscount William Slim of the British 14th Army in Burma wrote, “Some of us may forget that of all the Allies it was the Australian soldiers who first broke the spell of the invincibility of the Japanese Army.”

The Japanese had captured Rabaul on the island of New Britain in January 1942. They had been on New Guinea since March 1942. Their prime objective was the capture of Port Moresby for use as a staging area for further operations against Australia. The Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to seize the harbor, but the effort was turned back in the Coral Sea. Subsequently, the Japanese Seventeenth Army set out to capture Port Moresby from the north, across the Owen Stanley Range and down the Kokoda Track.

The Japanese Navy wanted to be in on the kill. Australian historian Dr. Peter Londey explained in a lecture at the Australian War Memorial, “The Navy wanted to save face by making its own contribution to the capture of Port Moresby, and thought that Milne Bay would make a good jumping-off point for an attack along the south coast.” The Allies, especially General MacArthur, had eyes on Milne Bay as well. After Coral Sea, MacArthur decided to establish an Allied base on the southeastern peninsula of New Guinea. On June 8, a 12-man party, three Americans and nine Australians, under the command of Lt. Col. Leverett G. Yoder, took off in a Catalina flying boat to reconnoiter Milne Bay. The patrol reported that Milne Bay possessed all the key features required for base development: a deep harbor, tracts of flat land, fresh water, construction materials, and supportive villagers.

MacArthur wanted to construct airstrips on the southern tip of New Guinea to guard Port Moresby’s flank, to strike Rabaul and other Japanese bases in the Solomons, and to develop a base for future operations along the northern coast. Milne Bay, 370 kilometers from Port Moresby, provided the best natural harbor on New Guinea. Its terrain and climate, however, were inhospitable for airstrips.

Milne Bay is 20 miles long and 10 miles wide with mountains near the shore that quickly rise to 4,000 feet in elevation. Slightly inland, the mountains reach 13,000 feet and give the impression of flying into a long, narrow funnel. A narrow coastal strip of land is choked with thick jungle. Hot, humid, and subject to torrential rains that turn tracks into quagmires, the Milne Bay area averaged 106 inches of annual rainfall according to an Australian wartime meteorology report.

A meteorologist stationed at Milne Bay wrote in his diary, “On an occasional day in the dry season, Milne Bay presents a magnificent panorama of translucent blue and green water, spectacular mountains and flamboyant vegetation. Exotic birds and reptiles abound. Myriads of insects, mostly mosquitoes, flit, buzz and sting. Malaria is rife; scrub typhus is common. On a clear night, fireflies flash like miniature neon lights. But, in minutes, the situation can change into an incredible darkness as clouds descend to the very surface of the earth, and torrential downpours obliterate everything.” The battle would be fought during the rainy season.

The narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea ranged in width from a few hundred meters to three kilometers at the widest point, perpetually soggy with sago and mangrove swamps. Before the war, Lever Brother had planted a large coconut plantation and built a company headquarters and a service building at Gili Gili. The dock consisted of two large barges with a ramp to a jetty. The very few roads consisted of crushed rock covering logs, which by 1942 were in terrible condition. The only coast road, a simple flat dirt path, ran along the north shore through the villages of Kilabo, Rabi, Kristian Bruder Mission station, Waga Waga, Wandala, and Ahioma. The plantation managers implemented malaria control measures including drainage, but the drains had fallen into disrepair. According to John Moremon, a contributor to the Australian War Memorial, “It was one of the worst places ever discovered for malaria—the disease classified as hyperendemic with up to 90 per cent of the villagers infected.” The Australian planters had abandoned the location by the time the Japanese took Rabaul.

Allied headquarters in Brisbane issued orders on June 12, 1942, to Company E, U.S. 46th Engineer Regiment and a company of Australian militia to proceed to Milne Bay. The engineers and two detached companies and a machine gun platoon from 55th Battalion, 14th Brigade, arrived on June 18. The commanding officer, American Colonel Frank Burns, reported difficulties immediately. There was little material in the area to aid them, no wharves, no ships, but the main problem was supply. Historian Harry Gailey described the logistical problem in his book MacArthur Strikes Back: “There were few ships available to bring in the necessary food, ammunition, and construction materials. From the beginning the workers were on a two-thirds ration of bully beef and biscuits.” It was not until July that a continuous shuttle of Dutch, American, and Australian supply ships was established.

A U.S. Army antiaircraft battery arrived on June 29 to provide air defense. On July 1, the engineers began work. The engineers and work details of Australians completed strip No. 1 in 22 days. They cleared 426 acres and felled 23,850 coconut trees. Private Peter Wright of the 55th Battalion, who guarded the construction and conducted patrols, recalled the Japanese air raids: “They often strafed the airstrip but the air raid warning system gave the troops enough notice to scramble into the foxholes.”

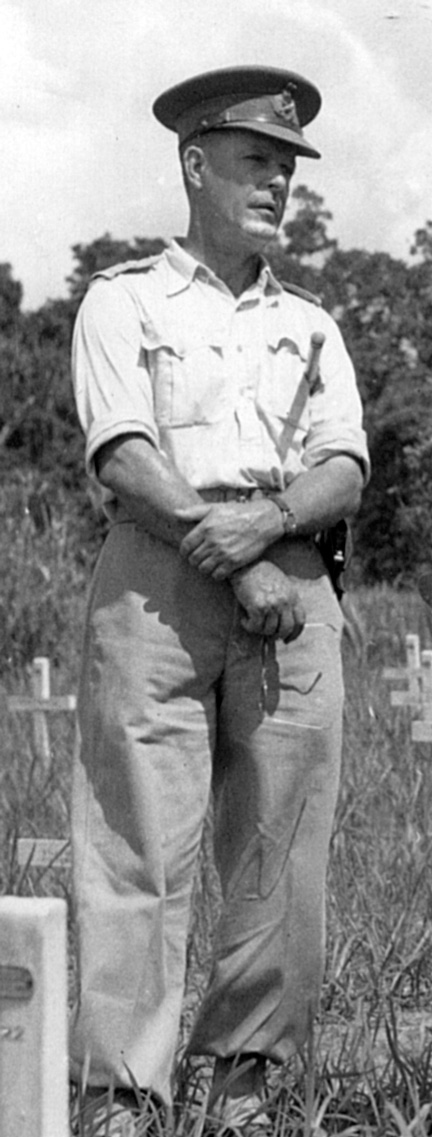

MacArthur strengthened the base defense, committing a militia brigade and support units called Milne Force. The main strength was the Australian 7th Militia Infantry Brigade, which consisted of the 9th, 25th, and 61st battalions, all from Queensland and commanded by Brigadier John Field. According to Australian military historian Peter Firkins, Field had been commissioned 18 years earlier, served as a mechanical engineer and university instructor, led the 2/12th battalion in Libya, and was promoted to command 7th Brigade a few weeks after returning from the Middle East. He was selected to lead Milne Force and helped to build the logistic foundation at Milne Bay, including the airfields, roads, bridges, wharf, and the defenses.

This was the first time these militiamen had served outside the mainland, but they were the perfect match for the situation. “The fighting in Papua well suited the individual qualities of the 7th,” noted historian John Costello. “It was largely a series of savage hand-to-hand conflicts, and there was less skill in maneuver. Milne Force also included light and heavy antiaircraft units and a battery of 25-pounders from the Australian 2/25th Field Regiment, along with the American 709th Airborne AAA battery armed with .50 caliber machine guns.”

Brigadier Field and 25th Battalion arrived on July 11. The detached company of 55th Battalion returned to Port Moresby. With additional manpower, the engineers and Diggers, according to the battalion’s war diary, laid 100 yards of landing strip each night, 1,500 yards by the time the Royal Australia Air Force arrived. The weather conspired to make the work back breaking. Private Francis Beitz was a stretcher-bearer attached to 8 Platoon, A Company, 61st Battalion, part of the battalion’s advance party. “The men were immediately put to work constructing and repairing roads for the trucks bringing supplies from the wharf,” he recalled of the daily grind. “Road construction was a never-ending task due to the constant, heavy rain, which continually washed out roads.” Eventually, 8th Platoon was sent to Taupota, a village on the northern coast, to prevent the Japanese from landing there and striking overland to Milne Bay.

The engineers finished Airstrip No. 1, on July 21. Without delay they began work on airstrip No. 2, two miles farther west at Waigani. Allied Headquarters immediately moved two RAAF squadrons, the 75th and 76th, and a composite squadron of RAAF Lockheed Hudson bombers from the 6th and 32nd Squadrons, which arrived on July 25. The air contingent consisted of 40 Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks and five bombers. On the rolls of the 76th Fighter Squadron were two of Australia’s most famous pilots, Peter Turnbull and Keith Truscott.

Peter “Hawkeye” Turnbull commanded 76 RAAF. At the age of 25, Turnbull flew combat in the Middle East, where he earned a Distinguished Flying Cross with 3 RAAF Squadron. He had also helped defend Port Moresby with 75 RAAF before commanding 76 RAAF at Milne Bay. Of Scottish stock, his former commanding officer, Ian McLachlan, considered him “the best of the early teams. He was quick to learn fighter tactics, was quick to the kill, and was able and courageous in leadership.” Turnbull fought German, Italian, and Vichy French pilots and bettered them all. He soon would encounter Japanese veterans.

RAAF historian J.C. Waters described what Turnbull faced upon arrival at Airstrip No. 1. “It was one of the worst air-combat areas and among the wettest. Six inches of rain fell in one day when the squadrons erected their tents. Machines bogged as soon as they left the runway. Rain squalls came down with the speed of diving aircraft. Ground crews worked and ate in the rain; mildew impregnated clothing, infested hairbrushes, and clung to blankets. Fever and dysentery attacked the pilots.”

“Bluey” Truscott, a well-known all-star Australian Rules footballer from Melbourne, arrived at Milne Bay in a roundabout manner. At the start of the war, he was posted to Canada, then to England where he joined the RAAF’s first fighter squadron, 452. Over England, Truscott achieved 16 victories and earned the Distinguished Flying Cross. “Bluey” participated in the famous Channel Dash and fought in North Africa. He was posted back to Australia to help train 76 RAAF, which was forming at Townsville. When the squadron arrived at Milne Bay, Truscott commanded the second flight of 12 P-40s.

The Aussie pilots named Airstrip No. 1 Gurney Airfield, after Squadron Leader Charles Raymond Gurney, who had been killed in action two months earlier. Two miles from the sea, Gurney, according to one pilot, “was virtually a swamp laid with matting of interlocked perforated steel plates.” Nonetheless, the RAAF began patrols throughout the area.

Milne Force arrived piecemeal during the month of July. Field’s force expanded as the main body of the 61st Battalion, nicknamed the Camerons, along with the 2/6 Heavy AA Battery, 11th Field Ambulance Battalion, and elements of the 9th Battalion, arrived on August 3. The first air raid on operational Gurney occurred the next day as Japanese Zero fighters and dive-bombers pounced, destroying a p-40. The Diggers knocked down a fighter and dive-bomber. Allied plans to expand and expedite the base construction shifted into high gear when D and F Companies of the American 43rd Engineer Regiment arrived on August 8, the day after the landing at Guadalcanal. The new engineer companies began a third strip at Kitabo, about three miles west of Gurney. By the time of the battle, the 43rd Engineers bulldozed a 2,000-foot strip, only 200 yards from the bay. The unfinished Airstrip No. 3 would be a critical factor at the climax of the battle. Field now commanded a total of 6,212 Australians and Americans.

Events elsewhere in the South Pacific had repercussions for Milne Force. The Japanese seized Buna, on New Guinea’s northern coast, on July 22. From there, the northern pincer of General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army was to assault Port Moresby. The second pincer, designated Operation RE, required the Navy to seize Milne Bay and attack Port Moresby along the southern coast. Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, commander of the Eighth Fleet, planned to use the Aoba Detachment, presently in the Philippines, and the 124th Regiment to occupy Milne Bay. Soon, however, the 124th Regiment was diverted to Guadalcanal. With the Army already in action and poor intelligence indicating a small Australian force at Milne Bay, he decided not to wait for the Aoba Detachment and cobbled together a force made up of available naval troops.

The RE forces consisted of 612 Marines from the 5th Kure Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), 197 Marines from the 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF), and 362 engineers from the 362nd Naval Pioneer Unit. These were to land at Rabi in Milne Bay. An additional 350 Marines from the 5th Kure SNLF would land at Taupota and march south overland to Gili Gili. Commander Shojiro Hayashi led the expedition. Mikawa gave Hayashi the command to proceed on August 22 with the following orders: “At the dead of the night quickly complete landing and strike the white soldiers without reserve, unitedly smash to pieces the enemy lines and take the aerodrome by storm.”

Melbourne codebreakers, however, had provided the Allied contingent at Milne Bay with valuable intelligence. Operating as part of the Fleet Radio Unit network code-named Hypo, the Melbourne codebreakers monitored radio traffic from Rabaul. In early August, Hypo informed MacArthur of the Japanese intention to attack Milne Bay. MacArthur believed the codebreakers and ordered the 18th Brigade of the 7th Australian Division, recently returned from North Africa, to Milne Bay. The brigade received its orders on August 3, sailed on the 7th, and completed its move to Milne Bay by August 22. In American Caesar, author William Manchester remarked, “Anticipating the end-around toward Moresby, he [MacArthur] had set a trap at Milne Bay and armed it with Mideast veterans of the 7th Australian Division.”

These were the Desert Rats, who exactly a year earlier had stopped Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the German Afrika Korps cold at Tobruk. The 18th Brigade consisted of the 2/9th Battalion from Queensland, 2/10th

Battalion from South Australia, and the 2/12th Battalion from Queensland and Tasmania. Commanded by Brigadier George Wootten, it also included two antiaircraft batteries, a field battery from 2/5 Field Regiment, and an antitank battery. Wootten had commanded the unit at Tobruk and was a tough, respected leader.

The Desert Rats slowly confronted the jungle. Captain Angus Suthers recalled, “It was a bastard of a place. It rained solidly for weeks, and the mud was waist deep in parts and if you fell, you drowned.”

One Digger wrote, “Even without the war Milne Bay would have been a hell hole—it was a terrible place. The sun hardly ever shined and it rained all the time. It was stinking hot and bog holes everywhere and it was very marshy, boggy country. It was a disease-ridden place.”

Neil Barrie, a stretcher-bearer of the 2/5th Field Ambulance attached to the 18th Brigade, recalled the local help: “Due to the constant tropical storms, most of the local roads were virtually impassable so the unit relied on the help of the local ‘fuzzy wuzzy angels’ who were familiar with the jungle tracks to move between the forward lines and medical aid posts. They helped save many lives.”

On August 22, command of the entire Milne Force passed to Maj. Gen. Cyril Clowes, a Duntroon graduate. Clowes was a Regular Army officer who had served with ANZAC forces during the campaign in Greece. For the first time in the Pacific, Australian Army and Air Force units came under one commander. This would maximize swift and efficient coordination between the ground and air support.

Clowes, like Wellington at Waterloo, set his defense by interlacing his veterans and the militia. The 2/9 Battalion guarded Gurney Airfield from a possible parachute drop. The 2/10 defended the Gili Gili beachfront from direct landings. The 2/12 was between airstrips No. 1 and No. 2 along Route 4. Clowes assigned the 9th Battalion, between 2/10 and 2/12, on the beachhead west of the wharf at Gaba Gabuna Bay along Route 9. The 25th Battalion protected the American engineers working at Airstrip No. 3, while one of its companies was northwest at Goodenough Bay. The 61st Battalion was scattered along the coast road with D Company at Ahioma, B Company at

Kristian BruderMission, and A Company at Motieau while Headquarters and the remainder of the battalion screened east of Airstrip No. 3.

Milne Force was at its maximum: 7,429 Australians, of whom 6,394 were combat troops and 1,035 were service troops. American strength, mainly engineers and antiaircraft personnel, numbered 1,365 men. The strength of the RAAF was 664 personnel. Clowes’ total strength was 9,458 men. He knew he would not receive any further reinforcements, and he also knew the Japanese were coming. The enemy had no idea they faced such a large force.

The first echelon of Japanese from Kavieng, bearing mostly 5th Kure troops, left Rabaul for Rabi on the morning of August 24, while the 5th Sasebo left Buna at the same time in seven large motor-driven barges. By now, only 12 of 76 RAAF’s fighters were serviceable. To soften up Milne Bay, 12 Japanese aircraft strafed the airstrips the same day. The Australian coastwatcher at Porlock Harbor on Cape Nelson caught sight of the Japanese forces and passed along the information to Allied headquarters. He reported three cruisers and three destroyers escorting two troop ships, 8,000 tons each; two tankers, 6,000 tons each; and two minesweepers. A second report indicated another force of seven motorized barges.

The RAAF went to work. A Hudson from 32 Squadron sighted the barges near Goodenough Island about 100 kilometers north of Milne Bay. The troops were ashore to rest and eat. Kittyhawks scrambled to hit them.

Twelve P-40s found the Japanese shortly before noon. “They made run after strafing run on the stationary targets,” wrote historian Harry Gailey. “When it was over, all the landing craft had been destroyed along with most of the stores and ammunition. Japanese troops were left stranded on the beach. This part of the plan had been foiled. There would be no attack on Taupota. The success of the Japanese offensive rested totally on the detachment from Kavieng.” The RAAF failed to locate the main Japanese fleet.

The next day, American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses from Cape York airfields and Martin B-26 Marauders from Townsville found the enemy fleet. Heavy cloud covering prevented the planes from scoring any hits. The weather broke in the afternoon, permitting the RAAF to attack. Carrying bombs fixed to their undercarriages, the Kittyhawks struck the RE invasion force, sinking a minesweeper and damaging a transport. However, the Japanese did not turn back. At about 10 pm, August 25, despite rain and fog, the Japanese landed nearly a thousand Marines and quickly established headquarters and a series of supply dumps at Waga Waga and in the Wanadala area. The beachhead cut off the Australian units at Ahioma and Taupota.

Historian Dudley MacArthy explained Clowes’ dilemma: ”Thinking he might be dealing with a landing force of up to 5,000 men and expecting further landings on either of the peninsulas north and south of his position, which would put large bodies of enemy troops in the flank or rear of his main position at the western end of the bay, Clowes had been obliged to play a cautious hand and initially kept the bulk of his units in reserve.”

Clowes did, however, attempt to recall the company at Ahioma. The Japanese began to push out patrols in both directions along the coast. The first shots of the battle rang out just before midnight near Ahioma. One of the boats filled with Australian troops ran into a Japanese patrol operating on a barge and was forced back to shore. The Australian company melted into the jungle and attempted to make its way back to the Gili Gili area. The 8th Platoon of A Company at Taupota remained in place. Anticipating an attack that never came, stretcher-bearer Beitz recalled, “The men at Taupota missed out on the main battle, although we did encounter some Japanese escaping from the battle area afterwards.”

Just after 1 am on the 26th, Australian and Japanese patrols bumped into each other east of the KristianBruder Mission. A screening platoon of B Company, 61st Battalion opened up with Bren gun and rifle fire. The Australians killed the four lead scouts but then withdrew to report a large force of Japanese soldiers accompanied by two tanks. An expected attack failed to materialize. The Japanese pattern of resting by day and fighting by night was not yet understood. In the morning, Commander Hayashi discovered something, too. The Japanese Navy disembarked his troops five miles east of Rabi, the intended site. They landed at the villages of Waga Waga and Wanadala, a full 10 miles from their objectives. He called up motorized barges to move the troops along the coast.

The pilots of both RAAF squadrons, as John Vader revealed in his book Pacific Hawk, had “vowed never to shave one side of their faces until the Japs were driven into the sea.” The Kittyhawk pilots took off at dawn on the 26th. Searching for the enemy in rain, fog, and clouds would not be easy. The Aussie pilots were aided by a single Japanese Marine who foolishly opened fire with an antiaircraft machine gun. Kittyhawks and Hudsons shuttled back and forth all day long. The P-40s destroyed most of the supplies that the Japanese brought with them. They also hit a disguised fuel dump. Most important, the RAAF squadrons sank every landing craft the Japanese had, forcing them to rely on the muddy coastal road.

First Hayashi had to take Kristian Bruder Mission, and B Company was ready for the attack. At 10 pm, the 5th Special Naval Force launched a highly coordinated attack with tactics that had been successful in Malaya. They hit the middle while other Japanese waded into the sea on one side and into the swamp on the other to outflank the Australians. Before being cut off, orders came down for the Diggers to withdraw. Lacking antitank guns and mindful of Japanese armor, the battalion commander withdrew a mile down the coast behind the Gona River, a natural tank obstacle. In spite of their success, the Japanese failed to occupy the mission. Instead, Hayashi waited for additional troops, which landed during the night.

Clowes moved the 2/10 Battalion forward to reoccupy K.B. Mission. The battalion passed through the exhausted militia company that had seen action earlier and lost 15 killed, 14 wounded, and several missing during the night combat. The 2/10 entered K.B. Mission in mid-afternoon on August 27 and formed a defensive perimeter. The 500 veterans of the desert campaign had traded heat, sand, and Germans for rain, mud, and Japanese. Australia’s best troops, men who had stymied Rommel, now faced the Japanese Marines. The Desert Rats were confident that they could halt the assault on Australia. But as historian Peter Firkins wrote, “The Japanese proved to be an even tougher foe than the Afrika Korps.”

The Japanese launched the attack at 8 pm in blinding rain. Supported by tanks, the infantry pierced the perimeter. Fighting became hand-to-hand. Without antitank guns or mines, the Australians depended on grenades and sticky bombs, but the rain and humidity rendered them useless. The Japanese attack split the battalion. Headquarters and two companies retreated into the jungle and did not get back to the plantation until August 30. By midnight the Japanese held K.B. Mission. The remainder of 2/10 withdrew to the Gona River along with B Company, 61st Battalion and dug in.

In the steady rain, the Japanese pressed forward with tanks and infantry. Just like in Malaya, the Japanese did not allow the Australians to set up a defense. By 2 am, the Japanese had overrun the river position. The Australians retreated to Airstrip No. 3, which was defended by the remainder of the 61st and 25th Battalions. The 61st Battalion lost 14 killed, 30 wounded, and 14 missing. The 2/10 Battalion, hit harder, lost 43 killed and 26 wounded.

Once again, the Japanese had driven back a numerically superior enemy. Historian Peter Firkins, in his book Australians in Nine Wars, explained why: “A comparatively small force of resolute and expertly trained Japanese troops, who synchronized perfectly with their supporting tanks, had made the attack work.” By the morning of August 28, the Japanese were on the verge of victory. The 5th Special Naval Force advanced over seven miles in three days of hand-to-hand fighting. Their troops outnumbered 10 to 1, the Japanese tanks tipped the scales. Now, the environment tipped the scales back to the Australians. The tanks did not cross the river with the infantry, instead sinking into the soup-like muck. Trapped, they became easy targets for the Kittyhawks. As the Japanese edged toward Airstrip No. 3, the Australians dug in.

Brigadier Field, in charge of the eastern defenses, prepared his position well. The partially graded strip offered a clear 2,000-yard field of fire. “The 25th and what was left of the 61st defended the partially completed airstrip,” wrote historian Harry Gailey. “He [Field] had his troops positioned on the south side of the strip. The end of the runway was only a few yards from the sea; thus the Japanese were forced to attack frontally. He placed the American antiaircraft battery, with its .50-caliber machine guns, at the eastern end of his defenses. The two companies of the 43rd Engineers, with their .50-caliber machine guns and 37mm antitank weapons, were sited in the center of the line and were covered by Australian troops on either side. This was the critical position, because the trail from Rabi crossed the strip at this point.”

The Kittyhawks strafed the Japanese throughout the 28th as they closed in on No. 3’s perimeter. The mud did not deter the sorties. One pilot recalled, “Mud caked inches deep on the wings and brakes. Water lay inches deep on the runway. There were water-filled hollows 50 yards long in the mesh. Planes took off and landed enveloped in slush, slithered dangerously this way and that. Mud-caked guns ran hot. Some had only two out of six that would operate.”

Flying at treetop height, the P-40s came in from the west over the heads of the Diggers, down the strip, firing at the enemy. Airstrip No. 1 was so close that barely were the wheels retracted before the guns blazed. The two squadrons slammed 85,000 rounds into the Japanese lines that day. An infantry liaison officer working in the RAAF Ops Tent provided the necessary coordinates, which resulted in precision fire.

Unexpectedly, Allied high command handed the momentum back to the Japanese. Afraid the airstrips would be lost, headquarters ordered 75 and 76 Squadrons back to Port Moresby on August 28. “Having close support from the RAAF in New Guinea was novel, and a great boost to morale, and indeed at times the only thing that allowed the Australians to prevail. Morale dropped markedly when the machines left,” commented aviation writer Felix Noble.

The Japanese and Australians fought artillery duels and conducted patrols over the next two days. Hayashi took the calculated gamble to wait for reinforcements rather than to push forward. The Japanese probed the Australian lines by speaking in English and giving false commands or verbal taunts. One commander reported after the battle, “To draw fire, the Japs made free use of English phrases—often in very good English. Some invited vigorous Australian replies: ‘Australian man, you go. Japan man, we come.’ To which was given the answer, ‘Come on, you bastard!’”

Shortly after midafternoon on August 29, the Diggers heard the hum of approaching planes. Thinking they were Japanese, they were relieved to spot the blue and white roundels as the Kittyhawks of 75 and 76 Squadrons returned to Milne Bay. The P-40s swung back into action strafing the Japanese positions. Both sides tried to soften the other up in preparation for the assault on the airstrip.

On the evening of the 29th, a Japanese convoy of one cruiser and nine destroyers landed 768 Marines, 200 of the 5th Yokosuka SNLF and 568 of the 3rd Kure SNLF. Commander Minoru Yano, who arrived that evening, was the senior officer present and took command of the Japanese forces. He used August 30 to bring the reinforcements into line next to Airstrip No. 3.

Brigadier Field also adjusted his defenses. He did not change the infantry’s position but moved the American antiaircraft guns to both ends of the airstrip, which set up a crossfire on the center of the line. Field also increased his indirect fire support by taking a calculated gamble. He moved the two mortar platoons attached to the Australian battalions guarding Airstrip No. 1 over to Airstrip No. 3. He also placed a 25-pound howitzer battery half a mile to the rear of the defense line as additional firepower.

The RAAF continued to fly constant close support missions throughout the days. This was beginning to take a toll on the Australian pilots. Biographer J.C. Waters described the condition of 76 Squadron’s fliers: “They were weary and mud-caked; they had dysentery; they had malaria; they had high temperatures, but not one of them would say so.” Their condition eventually cost the life of 76 Squadron’s commander, Peter Turnbull. His Number 2 Flight Officer described the action: “A Japanese tank was threatening our positions. Peter flew low to strafe it. He shot it up. His plane continued to go straight on and in. He didn’t pull out. Incessant fighting and lack of sleep had taken toll of his seemingly tireless energy.”

There was no sleep that night either, as the Japanese cruiser and destroyers returned to shell Gurney Field.

Air Force Command again got cold feet. On the 30th, the two fighter squadrons were ordered back to Port Moresby. Keith Truscott took matters into his own hands. He understood the impact the withdrawal would have on the battle and on the soldiers. Truscott made a popular decision to stick it out with the ground troops until the battle was won or his pilots had no planes left airworthy. The next 24 hours proved Truscott right.

The climactic battle began insignificantly enough. Just after midnight, an Australian in a forward listening post thought he heard a metallic sound. To check it out, the sentry fired a rocket, which illuminated several hundred Japanese massed for attack. It was the start of three separate attacks launched by the Japanese with the support of artillery and machine guns. They struck the seaward end of the strip first.

The Japanese directed mortar fire at the Australian positions and then followed the barrage with an infantry attack. The Australian militia, supported by American engineers manning .50-caliber machine guns and 37mm antitank guns, was ready for them. Gailey wrote, “Troops of the 7th Brigade, bolstered by U.S. firepower, met the onslaught with automatic weapons in what an official army report described as a ‘wall of fire.’ In the manner of earlier Japanese attacks, the ordinary soldier, despite their physical condition and sustaining heavy casualties, repeated their attacks throughout the night. There was no hesitation for small units to attack larger Australian forces. Not one Japanese soldier was able to cross the airstrip alive.”

The Japanese moved to the northern end of the airstrip and tried a fourth time. They came up against another brilliant militia defensive position sited on high ground and backed by the artillery and mortars of the regulars. Over 2,000 mortar rounds were called in during the night.

“As a close support weapon the 3-inch mortar was very effective, devastating in results and demoralizing in its effect,” said one Australian officer.

A Japanese Marine on the receiving end of a mortar barrage wrote in his diary about the night attacks: “We were like rats in a bag and men were falling all around. I thought we were going to be wiped out and then we were told to withdraw.”

Despite heavy fog and rain, the RAAF P-40s flew low and strafed the Japanese positions throughout the fight. Just before dawn a Japanese bugle sounded withdrawal. The Australians counted 160 Japanese dead littered in the killing zone of Airstrip No. 3. The Australians lost three killed and 12 wounded.

Brigadier Field transmitted a communiqué to his defending forces: “Brigadier Field wishes to convey to all ranks of Australian and U.S. forces under his command, his appreciation of the splendid effort and success achieved under difficult conditions. The spirit which has been shown is worthy of our highest military traditions and has taught the enemy to respect your quality. These are proud days for our countries and for your comrades.”

Brigadier Clowes did not miss his opportunity to finish off the enemy. Clowes ordered the 2/12th and B and C Companies from the 2/9th to counterattack. Close air support would continue in the attack after a number of selected infantry and artillery officers briefed the pilots on enemy targets and friendly dispositions.

At 6:30 am in pouring rain, 2/12’s A, B, and D Companies moved out as the battalion war diary said, “knee deep in mud.” The companies passed through 61st Battalion across the open strip. Lieutenant Neil Russell of 2/12, from Coorparoo, Queensland, had been a platoon sergeant at Tobruk and led the battalion’s first platoon across the line of departure that morning.

Corporal Geoffrey Holmes, in his first battle, recalled his initial impression of combat and the Japanese: “I was met with the vision of dead Japanese strewn across the ground and concentrated around a mountain gun. I was struck by the features of the dead Japanese. I did not expect the Japanese to be so tall. I noticed anchor tattoos that marked their arms and assumed they were marines. Most of all I was amazed by the prevalence of stainless steel teeth among the Japanese, which also seemed to create a sense of eeriness amongst the dead.”

The momentum of the assault carried the companies through snipers, rear guards, and isolated Japanese Marines all the way to K.B. Mission. The coordinated fire again proved decisive. One infantryman commented on the close air sorties: “Palm fronds, bullets, and dead Japanese snipers were pouring down with the rain.” D Company assaulted K.B. Mission with a bayonet charge at midafternoon. The Diggers stormed into the Japanese position, and a nasty hand-to-hand fight ensued. The Australians killed 60, and the Japanese immediately launched a savage counterattack from the jungle. The pitched battle lasted 40 minutes, and the Japanese Marines broke off the fight when A Company arrived.

It was at K.B. Station that the Australians found their first evidence of Japanese atrocities. Captain Angus Suthers was with the squad that made the grisly discovery. “K.B. Mission’s where we found the Aussie prisoners, trussed to a tree and stabbed full of holes. The Japs had used them for bayonet practice. It was brutal, cruel and inhuman. They behaved like bastards.”

Feelings of disgust even reached the commanders, as Brigadier Field wrote in his personal diary: “The yellow devils show no mercy and have since had none from us. After that, there were no prisoners taken.” Corporal Holmes, the green infantryman, also saw the massacre. The experience had a profound effect on Holmes even decades later. He explained at the 60th anniversary ceremony: “There is still a strong hatred of the Japanese as individuals, not their doctrine or anything else, hatred against the troops I was up against … you had to kill them to beat them.”

Historian Dr. Peter Londey recounted extensive Japanese atrocities during the battle: “In their few days at Milne Bay, the Japanese displayed remarkable brutality. The Webb Commission into Japanese atrocities listed 59 cases of local people murdered by the Japanese, often being bayoneted while held prisoner, and in many cases being tortured and mutilated. Not one of the 36 Australians captured by the Japanese in the course of the battle survived. All were killed, and some were badly mutilated.”

That night two companies of 2/12 were at K.B. Mission and two at Rabi on the Gona River, while one company of 9 Battalion was between the Mission and Rabi and another company in reserve at Rabi. During the night, 2/12 was struck by elements of the Japanese force. The largest attack was at Rabi when 300 Japanese slammed into the river position out of the jungle from the north. Company B took the brunt of three separate attacks. “Charging out of the jungle with maniacal screams, they struck just at dusk,” wrote Peter Firkins. “For the next two hours there was a confused savage struggle in slashing rain with the opponents fighting in mud which in places was knee-deep. After a severe mauling the Japanese fell back.” The company killed over 90. Companies A and D at K.B. Mission defeated an assault, inflicting over 20 dead.

Clowes planned to push on to Ahioma the next day, but the torrential rain wiped out the roads. This plus a false invasion report from MacArthur’s headquarters forced Clowes to keep his units in place. It took two days to shuttle the rest of 2/9 Battalion across the bay to position itself as the lead unit in the advance. During the reshuffle, the Japanese continued to harass the Australian positions.

The medical facilities provided outstanding service despite the terrain and climate. The general hospital, with two field ambulances, was located between airstrips No. 1 and No. 2. Medical battalions were sprinkled from the general hospital to Airstrip No. 3. During the first seven days of fighting, the surgeons performed 96 operations, and the wounded overflowed the ward as cots were set up in native huts. By September 2, there were 365 sick and 164 battle casualties held in the facilities. The hospital ship Manunda was ordered to Milne Bay to assist.

Clowes was ready to resume the attack on September 3, but the respite permitted the Japanese to dig strong fixed positions that the Australians would have to take out one by one. When the lead battalion kicked off the offensive, it faced two days of very stiff resistance. The 2/9 advanced a mile east of the Mission on the first day.

The Japanese were desperate. Commander Yano, himself wounded, led the rear-guard action, hoping to buy time for reinforcements. Determined to accomplish this, he radioed Rabaul, “Everyone resolved to fight bravely to the last.” By nightfall, the Diggers of 2/9 reached the village of Goroni, two miles east of K.B. Mission. The battalion lost eight killed and 22 wounded. Here the Australians faced even stiffer Japanese resistance.

The battalion moved forward in the morning. Machine-gun nests, coconut log rifle pits, and fanatical Japanese stalled the Australians all morning. Inch by inch the Diggers moved forward only to be stopped dead in their tracks by the Japanese. The Australians regrouped. The battalion launched another attack around 3 pm, supported by mortars and artillery. The Japanese seemed on the verge of repulsing this attack when Corporal John French, a veteran of the North African campaign, turned the course of the battle.

His posthumous Victoria Cross citation reads: “A company of Australian infantry encountered terrific rifle and machine-gun fire. The advance section of which Corporal French was in command was held up by fire from three enemy machine-gun posts, whereupon, Corporal French, ordering his section to take cover, advanced and silenced one of the posts with grenades. He returned to his section for more grenades and again advanced and silenced the second post. Armed with a Thompson submachine-gun, he then attacked the third post firing from his hip as he went forward. He was seen to be badly hit by fire from the post, but he continued to advance. The enemy gun ceased to fire and his section pushed on to find that all members of the third gun crew had been killed and that Corporal French had died in front of the third gun pit.”

The 2/9 broke the defensive line by the end of the day. It cost another 18 killed and 34 wounded. The same day, the body of Squadron Leader Turnbull was discovered among the remains of his Kittyhawk in the bush near K.B. Mission.

The battalion continued to advance during the next several days. Corporal Stanley Powell, from Maryborough, Queensland, described D Company’s contribution to 2/9’s advance: “D Company was held in reserve early in the battle, then moved forward to engage the Japanese. The 2/9th pushed the enemy force back to their evacuation points. We went into action around K.B. Mission, Elevala Creek, Goroni and Waga Waga. On the last day of the battle, I was wounded in the leg and evacuated by the hospital ship, Manunda, to Australia.” From September 1-5, the Australians lost 45 killed and 147 wounded. The Japanese barely held on.

The Aoba Detachment finally arrived at Rabaul on September 5. Preparations were made to land on September 12. Admiral Mikawa designated Captain Yoshitatsu Yasuda as new overall commander of the Milne Bay expedition. But Yano informed Mikawa that his soldiers were near a state of exhaustion and could not hold out for another week. Mikawa cancelled the move and tried to save as many of the trapped Marines as possible. During the night of September 6, Japanese ships slipped quietly into the bay and evacuated 1,318 men. The Australians advanced the next day and found the base deserted.

The last Japanese naval bombardment hit the coastal positions on September 7. The Japanese got in one last air strike when the skies cleared on the 8th. Clowes shifted 2/9 back to Gili Gili the same day. It had suffered 30 killed and 90 wounded during the offensive. The 12-day battle cost Milne Force 373 casualties, of which 167 were killed or missing. The Americans suffered 14 deaths, all from the 43rd Engineer Regiment. The Japanese suffered 311 killed and 700 missing.

The Australian pilots, as Harry Gailey said, “had done yeoman’s work.” The RAAF destroyed 23 Japanese aircraft during the course of the battle. By the end of the fight, only 17 of the original 40 Kittyhawks were serviceable. According to Noble, “The two squadrons fired approximately 200,000 rounds of ammunition and wore out three hundred gun barrels. Nine Kittyhawks were destroyed and seven pilots killed.”

Major General Clowes recorded his appreciation of the pilots’ work soon after the engagement: “When the story is complete it will be found that their incessant attacks over three successive days proved the decisive factor in the enemy’s decision to re-embark what was left of his force.” American Air Force General George Kenney added his endorsement and “earnest appreciation of their tenacity, determination, and fearlessness.”

Unfortunately, MacArthur and Australian Supreme Field Commander General Thomas Blamey assessed the Australians differently. Both commanders were very critical of Clowes. At Allied headquarters in Brisbane, Blamey commented, “It seems to us here by not acting with great speed Clowes had missed the opportunity of dealing completely with the enemy.” MacArthur, who only remembered Australian defeats in Malaya, wondered about the Aussie. He could not understand why 4,500 ground troops had not speedily repelled 1,900 Japanese. Following an investigation, it became clear that the Australian soldier had fought magnificently under incredible conditions against a confident and previously undefeated enemy.

Besides destroying the myth and hurling back the Japanese, did the Aussies achieve anything else of significance for their losses? As the Allies developed Milne Bay as a forward logistical base, it was featured in the master plan for the recapture of Japanese occupied territories throughout the South Pacific.

Sixty years later, 20 veterans, including Beitz, Wright, Powell, Russell, and Barrie, flew to Milne Bay to dedicate war memorials for Turnbull, French, and the 161 others buried in the war cemetery there. Only the men who faced the Japanese in the nose-to-nose death struggle survive today. The generals are long gone.

Today, the survivors’ assessments of why, how, and what their victory meant are simple and straightforward. Milne Bay veteran Peter Wright, of central New South Wales, sums it up best: “We were the 18-year-old kids who went up there to do a man’s job under adverse conditions. We did the job we were given to do.”

James I. Marino is a teacher in Hackettstown, New Jersey. He is also a football coach and World War II reenactor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments