By Joshua Shepherd

Smoke drifted across the quarterdeck of H.M.S. Vanguard, occasionally obscuring the figure of a slender officer bowed with battle wounds and outright exhaustion. At 39, Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson was already considered one of Britain’s most gifted naval commanders. But on the morning of August 2, 1798, a gravely wounded Nelson, surveyed the aftermath of one of the most furious naval battles of the eighteenth century.

Anchored at Aboukir Bay near the mouth of the Nile River, the Vanguard now sat mute witness to the horrific carnage after Nelson’s ships had all but destroyed the enemy fleet. The human wreckage left in the wake of the fighting was an appalling reminder of the reality of war.

While Nelson surveyed the scene of his victory, common sailors did the same. John Nicol, a hand aboard the Goliath, went above decks for a view of the bay and was sickened by what he saw.

“An awful sight it was,” recalled Nicol, “the whole bay was covered with dead bodies, mangled, wounded and scorched, not a bit of clothes on them except their trousers.”

By the summer of 1798, Britain and France were locked in an epic struggle that persisted for two decades and would eventually decide the fate of Europe. Ignited by the revolutionary upheavals that rocked France during the 1790s, the conflict had been joined by the Continent’s major powers, including Austria, Prussia, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. The Allied coalition, though it possessed overwhelming force, was plagued by dissension and conflicting strategic goals. By 1797, Britain alone remained at war with the French Republic.

The mounting danger to Europe’s delicate balance of power was increasingly personified by the French General Napoleon Bonaparte. The upstart Corsican had emerged from humble roots, risen through the commissioned ranks of the French Republic, and made a name for himself as a shrewd tactician during brilliant campaigns against Austrian forces in Italy.

Clearly an enterprising officer whose star was on the rise, Bonaparte developed an ambitious and highly original idea aimed at striking Britain where it was most vulnerable.

Rather than directly confront the imposing naval and military forces that Britain could muster in her defense along the English Channel, Bonaparte forwarded an audacious plan to invade and occupy Egypt. Although the nation was technically a part of the Ottoman Empire, seizing Egypt would threaten the vital trade routes to Britain’s lucrative colonial possessions in India.

Early in 1798, Bonaparte began marshaling a field army as well as forming a transport fleet at the Mediterranean port of Toulon. Eventually heading up an expeditionary force of 35,000 men, Bonaparte sailed from Toulon on May 19. The sudden appearance of a substantial French army on the Mediterranean ensured that the conflict was global in scale and could potentially pose a threat to the commercial survival of the British Empire.

The commander of Bonaparte’s fleet was a veteran officer of lengthy service and solid reputation. Vice Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigalliers, Comte de Brueys, had been in the French naval service since the age of 13. A scion of French nobility, Brueys had seen extensive action in the Mediterranean, as well as in North American waters, where he served against British naval forces during the American Revolution.

Despite his noble birth, Brueys survived the revolutionary purges that swept France. Brueys was experienced, dependable, and personally brave under fire. Although he had not commanded a major naval action, he was one of the best French officers available, and was personally selected by Napoleon to command the naval component of the expedition to Egypt.

Unfortunately for Brueys, his opposite number was one of the best officers from a nation that prided itself on centuries-old naval dominance. Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson had served Britain at sea since he was 12. Quickly exhibiting a remarkable proclivity for the naval service as well as a steely resolve, Nelson was given command of his own vessel at 20.

Nelson would rapidly gather laurels during the conflict with revolutionary France, seeing extensive action in the Mediterranean. Cool under fire and tactically adroit, Nelson had survived multiple engagements but had more than his fair share of scars to prove it. In action off Corsica in 1794, enemy fire had nearly blinded Nelson in his right eye. At the Battle of Santa Cruz in 1797, a French musket ball shattered his right arm, which was subsequently amputated.

By May of 1798, alarming intelligence regarding developments in the Mediterranean had thoroughly rattled the British Admiralty. Although precise French plans remained a mystery, Napoleon was clearly hatching something big. Nelson’s squadron was ordered into the region on a scouting mission but he would be dogged by misfortune throughout the campaign. Nelson’s flagship, the Vanguard, was nearly wrecked in a storm, and the French fleet was nowhere to be found in the vicinity of its home port at Toulon. As far as Nelson could determine, Napoleon and his army had vanished into thin air.

The hunt was on. Reinforced by an additional 11 capital ships on June 7, Nelson was nonetheless plagued by a woeful deficiency of fast-sailing frigates that could fan out and locate the French fleet. Nelson began his search with little information to go on. After passing Elba and Naples, Nelson received reports that the French fleet had been spotted off the coast of Sicily and was presumed to be headed toward Malta.

On June 22, Nelson received solid intelligence that the French fleet had been seen sailing east from Malta. Lacking confirmation, Nelson was forced to make a strategic guess. Perusing his maps, he came to the conclusion that Bonaparte intended to target Egypt, and ordered his fleet to immediately make sail for Alexandria.

Unknowingly, the two fleets barely missed a collision that night, passing within a few miles of each other in the dark. On June 28, Nelson reached Alexandria Harbor to find the French fleet nowhere in sight. Desperate to locate the enemy ships, Nelson turned his own fleet toward Turkey, then back toward Sicily.

He had come remarkably close to stumbling on the French. The day after the British fleet departed Alexandria, French frigates appeared at the harbor in preparation for the invasion. Subsequent to making landfall, Napoleon seized Alexandria and then consolidated his hold on Egypt by crushing Ottoman forces at the Battle of the Pyramids on July 21. Although Napoleon preferred that Brueys remain in Alexandria Harbor, the French admiral decided instead to anchor his fleet in the protected waters of Aboukir Bay to the northeast.

Nelson meanwhile, still unsure of French intentions, refitted at Sicily and then headed east, still hoping that fortune would turn in his favor. On July 28, it did just that. Off the Greek coast, Nelson finally received word that Napoleon had, indeed, launched an invasion of Egypt. In short order, Nelson’s ships were under full sail in a desperate attempt to make contact with the enemy fleet.

By August 1, the scattered British fleet reached Alexandria, but Nelson’s hopes of finding the French were dashed. The harbor indeed contained French vessels: transports guarded by a handful of frigates. The bulk of the French fleet had, once again, seemingly vanished. A despondent Nelson, desperate for any information of his enemy’s whereabouts, ordered the Zealous and the Goliath to scout northeast along the coast.

At 2:45 p.m., British fortunes made an abrupt and miraculous turn. The Zealous and Goliath sailed about nine miles before rounding a narrow spit of land and turning toward the sheltered waters of Aboukir Bay. High in the rigging of the Goliath, a bleary-eyed midshipman caught the unmistakable sight of white canvas dotting the blue waters of the bay. The rest of the fleet was hurriedly signaled. At long last, Nelson had discovered the elusive fleet of the French Republic.

With over nine miles separating the two fleets, it was obvious that if Nelson launched an immediate attack, the impending fight would take place in gathering darkness and dangerous shallows unfamiliar to the British. Nelson characteristically opted to go in for the kill and the fleet was signaled to prepare for battle.

The British fleet, scattered as it was, got underway immediately, slowly closing the distance to Aboukir Bay. While crews beat to quarters and gun decks were cleared for action, Nelson issued crucial orders, signaling for his captains to attach springs, or ropes used for adjustment, to anchors. When the fight was joined, such a technique would ensure that British ships, once anchored in line of battle, could still be turned in order to maximize the effect of their broadsides.

To gain access to Aboukir Bay, the British fleet had to swing wide to the east, bypassing a narrow isthmus guarded by Aboukir Castle, as well as Aboukir Island (now Nelson’s Island), guarded by French guns. Once past the island, the British had greater worries: perilous shoals that threatened to ground the heavy ships-of-the-line. About 5 p.m., Nelson’s ships roundied the shoals shielding Aboukir Bay and the setting sun revealed the grand French fleet at anchor.

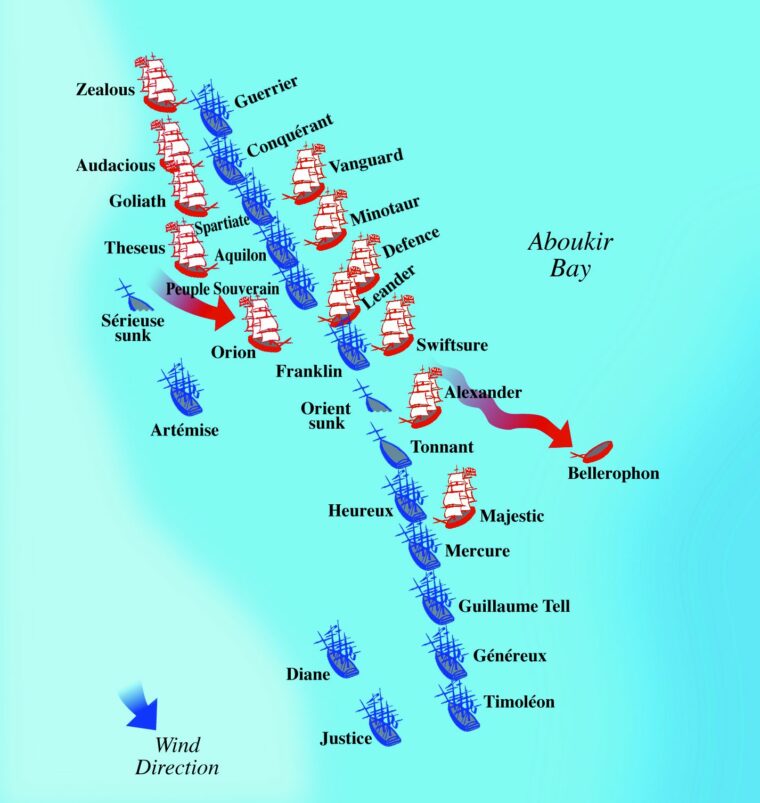

It was obvious that Nelson would be in for a tough fight. Although trapped at anchor in the western reaches of the bay, the French fleet was still imposing. Admiral Brueys commanded 13 ships-of-the-line as well as four frigates. Brueys’ flagship, positioned in the center of his line, was the towering 120-gun Orient. The rear of the French line was dominated by 80-gun ships. The French ships’ bows were oriented to the north, with their starboard batteries facing the bay.

As he sailed into the narrow confines of the bay, Nelson opted to target the head of the French line. With the enemy anchored roughly north to south and with the wind coming from the northwest, Nelson hoped to target the most vulnerable section of the French line and destroy it in detail before the French rear could offer any assistance.

By the time Nelson’s ships entered the bay, Captain Thomas Foley of the 74-gun Goliath had taken the lead of the British line. Foley was a veteran naval officer who possessed aggressive tactical instincts. The ships of the French fleet had run out their starboard batteries in preparation for the fight, but Foley decided to cross in front of the lead French ship, Guerrier, then swing south on the opposite side of the French line. The move caught the French off guard, and Foley proceeded steadily on course with four sister ships in tow.

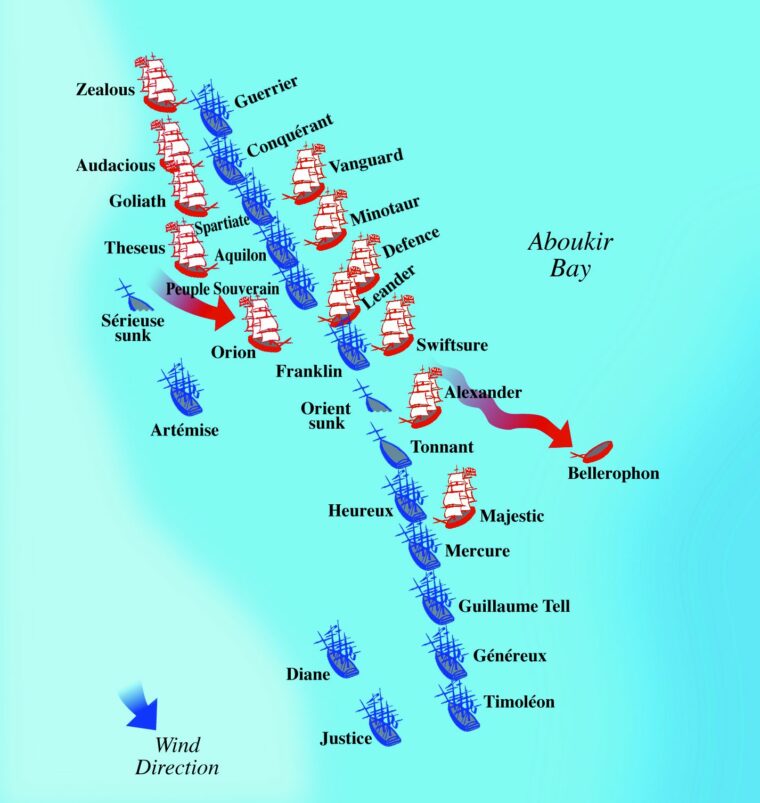

Foley was keen to exact grim punishment on the enemy, and his gun crews exercised the fire discipline characteristic of the British Navy. But as he crossed in front of Guerrier’s vulnerable bow, the British captain shortened sail in order to slow his ship. As he did so, he ordered a devastating raking fire from his port batteries. The full weight of the British broadside crashed lengthwise through the French vessel, crashing through her oak hull.

When Foley turned Goliath to the south, the French vessel was in for worse punishment. Captain Jean-Francois Troullet had only run out his starboard guns, and was totally helpless to confront the Goliath when it turned along his port. British gunners once again let loose a full broadside at nearly point-blank range. The fire ripped into Guerrier as her crew frantically scrambled to get their port guns into the fight.

Right behind Goliath sailed Captain Samuel Hood’s Zealous, which unleashed a broadside as it, too, crossed Guerrier’s bow. Hood then anchored in place beside Guerrier and commenced a furious close-quarters fight as fast as the British crews could load and fire their guns. In the opening minutes of the battle, Guerrier had already taken severe punishment. Her surgeries were rapidly filling with wounded men, the vessel’s foremast had been cut in half by a well-aimed solid shot, and her port batteries had barely been able to return fire.

The Goliath, meanwhile, was in search of her next victim. Foley moved to the next French ship, Conquerant, where he dropped his anchor and settled in for a toe-to-toe fight. It was an 80 to74 gun mismatch, and the British tars, seasoned by years at sea and regular gunnery drills, far outpaced their opponents, shattering the hull of the French ship, knocking out enemy guns, and decimating the crew. The French, only moderately trained and largely inexperienced, fought manfully but took the worst of it.

At the head of the French line, Guerrier continued to take an unabated battering. Three more British ships—the Orion, Audacious, and Theseus —had followed Foley, and each ship in turn delivered a devastating broadside as it passed Guerrier’s bow. Captain Ralph Miller of the Theseus, recognizing that the French ship was badly damaged, closed in for the kill. The two ships were nearly touching when Miller crossed the bow of the stricken vessel, and his well-timed broadside wreaked devastating carnage. Ripping lengthwise through Guerrier, Theseus’ solid shot tore the ship to pieces in a hail of oak splinters and mangled bodies. The manhandled French ship lost her remaining masts. Isolated knots of brave French sailors continued to fight on, but Guerrier had effectively been knocked out of the battle.

The five British ships that had crossed to the far side of the French line had succeeded in badly mauling the unprepared port of the enemy vanguard. As the Orion moved into position, it fired a heavy broadside into the frigate Serieuse, which fled to the shallows and quickly sank. Orion then anchored in position to attack both Peuple Souverain and Franklin.

The Audacious and Goliath teamed up opposite Conquerant, a badly unprepared ship that possessed a woefully understrength crew. The two British ships delivered a merciless pounding. Conquerant’s main and mizzen masts were soon down, and over 200 Frenchmen littered her blood-soaked and fire-swept decks.

While the battle raged, the situation only worsened for the French. Nelson, standing bolt upright on the quarterdeck of the Vanguard, was finally bringing his own flagship into the fight. With much of the French van badly chewed up, Nelson turned his vessel down the starboard side of the enemy line looking for fresh quarry. He found it in Spartiate, which was already taking fire from the Theseus on the port.

The two British ships commenced a brutal pounding of the French vessel but found a worthy opponent in her commander, Captain Maurice-Julian Emeriau. Emeriau commanded one of the newest vessels in the French fleet, and her crew gave a good accounting of themselves. Despite being trapped in the crossfire of two British men-of-war, the Frenchmen sternly stuck to their fighting positions, trading broadside for broadside.

The battle was, thus far, unfolding precisely to Nelson’s intentions, with the van of the French line being overwhelmed by a concentration of superior British firepower. But while Spartiate was slowly being battered into submission, Captain Miller of the Theseus inexplicably pulled away in order to engage Aquilon.

Miller later explained that he was leaving the honor of the victory to Nelson, but the immediate results were far from helpful. With the threat to his port suddenly removed, Emeriau ordered his entire crew to man the guns of his starboard batteries, which increased their fire into the Vanguard.

Locked in a death struggle, the two ships were wreathed in clouds of smoke as they pummeled each other. The decks of both vessels were transformed into killing grounds as they were swept by a hailstorm of iron and lead. Aboard Spartiate, sailors fell by the score. Despite the fact that the British were gaining the upper hand, they likewise suffered heavy casualties in the process. In a mere ten minutes, Vanguard lost more than 50 men.

One of those struck was Nelson, who was hit in the forehead and collapsed. Streaming blood, Nelson blurted out “I am killed, remember me to my wife.” The admiral, however, would survive. The wound was ugly, a deep cut across his forehead, but far from mortal. While Nelson was carried below to surgeons, the battle raged unabated.

By 10 p.m., the British were succeeding in smashing the head of the French line. Aquilon was forced to surrender. Peuple Souverain struck her colors after its captain had both of his legs ripped off by artillery fire. The captain of Spartiate surrendered his sword to a boarding party of Royal Marines; the trophy was eventually delivered to the wounded Nelson. But despite the tremendous success that the battle had thus far produced, Nelson’s fleet had yet to encounter the French center.

Breaking the French center appeared to be a herculean task. The center of the line was occupied by the frowning Orient, the 120-gun flagship of the fleet and crown jewel of the French navy. Orient was protected fore and aft by Franklin and Tonnant, 80-gun ships-of-the-line commanded by capable officers.

The first British ship to enter the breach was the Bellerophon, commanded by Captain Henry Darby. Darby brought his ship directly alongside Orient, dropped his anchor, and settled in for a grim contest with the French giant. Not unexpectedly, his ship took a beating from the outset. Darby’s crew traded broadside for broadside amid a thunderous roar of artillery, but, despite superior British gunnery, the men of the Bellerophon were badly outmatched. The 120-gun French behemoth pounded the Bellerophon to splinters, cutting two masts in half, wrecking 16 of her guns, and littering the decks with 200 casualties.

Darby, himself badly wounded, cut his anchor cable and escaped the fray, entirely removing his disabled ship from the battle. Despite the one-sided nature of the fight, the crew of the Bellerophon had succeeded in exacting a grim punishment on Orient. The initial weakening of her hull and crew, though purchased at great price, would later prove crucial.

While the Bellerophon was fighting its duel with Orient, Captain George Westcott experienced an unfortunate stroke of bad luck as he took his Majestic toward the French line. Helplessly tangling his ship in the limp canvas hanging from Tonnant’s foremast, Westcott was caught under the broadsides of his opponent but largely unable to return fire. While Tonnant made the most of the situation, the French ship Heureuse joined the fray, adding her own guns to the merciless pounding of the Majestic.

Amid the bloodshed, Westcott went down with a musket ball to the neck and First Lieutenant Robert Cuthbert assumed command. He succeeded in cutting the Majestic free, and then attempted to slip the vessel between Heureuse and Mercure, where he could rake both enemy ships. Misfortune, however, was Majestic’s lot. As Cuthbert attempted to slide between the French vessels, he ran into a cable strung between them. Stopped cold, Majestic fought on, losing her main and mizzen masts and over 150 men. She did, however, hurl an astounding amount of iron at her assailants, tearing up both French ships.

As Captain John Peyton brought the Defense into action, he came up along the starboard of Peuple Souverain, which was already sorely pressed by the Orion off her port. The crew of the French vessel had fought valiantly since the outset of the battle, but the overwhelming British firepower hastened the inevitable. Her masts shot away and the crew decimated, the ship was forced to surrender.

As the rest of the British began to approach the French fleet, disaster befell one of Nelson’s best officers. Captain Thomas Troubridge of the Culloden, in his haste to make for the fighting, rounded Aboukir Island far too closely, abruptly running aground in the shoals south of the island. Culloden, with a pierced hull, began taking on water at an alarming rate. Despite the crew’s best efforts, the ship couldn’t be freed from the shallows. Frustrated at his dilemma and raging at his bad luck, Troubridge, and the vital 74 guns under his command, was unable to join the fight.

Despite Culloden’s costly mishap, Nelson’s unengaged ships continued to join the battle, inexorably tilting the balance in his favor. As he brought the Alexander into action, Captain Alexander John Ball made a crucial split-second decision. Rather than attack the French line from starboard, Ball directed his ship to slip across the rear of Orient. His execution of the maneuver, the vital “crossing the T” of eighteenth-century naval warfare, began the unraveling of the French battle line.

From his port batteries, Ball battered the unprotected bow of Tonnant. The commander of the ship, Commodore Aristide Aubert Dupetit-Thouars was badly mangled, losing a leg and both arms. He refused to quit his deck and died with his men.

From his starboard guns, Ball sent shells crashing into the virtually undefended Orient. Though a fearsome giant in a stand-up fight, Orient proved an enormous, helpless target at anchor as the Alexander poured broadside after broadside into the massive ship’s stern.

The Swiftsure lent its metal to the fight. Under the command of Captain Benjamin Hallowell, the ship assailed both Franklin and Orient’s port rear quarter. With Alexander and Swiftsure’s guns rapidly belching fire and iron, weakened French crews began to crumble under the pressure.

Amid the nightmarish fight of the big ships, one of Nelson’s smallest vessels fearlessly pitched into the battle. Captain Thomas Thompson’s Leander, technically a ship-of-the-line, was nonetheless an antiquated 50-gun vessel that only slightly outmatched a frigate. Undaunted, Thompson crossed the T in front of Franklin and poured a crushing fire into the French ship’s bow. The 80-gun Franklin, beset by a swarm of British ships, was consequently being battered to pieces by Defence, Leander, Orion, and Swiftsure.

Aboard the Orient, morale plummeted and defenses began to crumble. Attacked simultaneously by Alexander and Swiftsure, the French flagship had suffered heavy casualties and many of her batteries fell silent for scarcity of gunners. To his credit, Admiral Brueys had fought nobly. Wounded in the arm and head, the admiral’s uniform coat was spattered with his own blood.

But as he continued to direct the fight, a careening British shot struck Brueys in the midsection, nearly cutting him in half. Terrified onlookers attempted to move him below decks but Brueys, resigned to his fate and grim to the last, refused to leave his crew. Lying on deck in his own gore, Brueys amazingly lived for another quarter hour, the French colors still flying above his ship.

Orient, however, was doomed to share the fate of the admiral. British sailors battling the French flagship suddenly noticed that a fire had broken out in the rear of the vessel; for ships in the age of sail, there was no greater peril. French sailors could be seen scrambling about the decks in an attempt to fight the fire. Aboard Swiftsure, Captain Hallowell coolly ordered his gunners to target the French sailors, discouraging further efforts to stop the blaze.

As British guns continued to batter Orient, the fire on the French ship began to rage out of control. The water pump needed to douse the fire had been shattered by British artillery, and the French crew was helpless to halt the blaze. In short order, flames spread along the length of the ship, igniting the deck, masts, and sails. The terrifying inferno lit up the bay, and men from both sides stood temporarily transfixed. Aboard the Vanguard, the stricken Nelson was carried above decks in order to take in the sight.

It was a surreal scene that onlookers intuitively realized would get disastrously worse. The raging fire grew so hot that tar began to melt out of the seams in Swiftsure’s hull. Orient’s crew desperately attempted to soak the contents of the ship’s powder magazines, but the conflagration grew so hot that they were forced to give up the attempt.

When it became increasingly apparent that Orient’s powder stores couldn’t be protected from the flames, bedlam erupted. The doomed ship’s crew began leaping overboard, preferring the black waters of Aboukir Bay to the disaster that was sure to come. All around Orient, both French and British ships that had been locked in a death struggle for hours began hastily cutting their anchor cables in order to get away.

While most ships fled for safety if they could, Captain Hallowell of the Swiftsure remained cool. Retaining his position in line, Hallowell maintained fire on Orient and Tonnant, all the while busying work crews in wetting his sails and decks. When he reckoned that he had pressed his luck as far as he dare, Hallowell had his gun ports closed and ordered his sailors to seek cover.

And then it happened. It was slightly past 10 p.m. when the flames finally reached Orient’s powder magazines, and a shocking explosion obliterated the French vessel. In an enormous fireball that could be seen for miles, shattered debris was blown thousands of yards in every direction, leaving the surface of the bay littered with the ghastly flotsam of shattered oak, charred canvas, and broken bodies. Witnesses of the horrific conflagration would never forget the sight. Watching in awe from the quarterdeck of the Theseus, Miller thought the explosion of Orient “a most grand and awful spectacle.”

As the explosion subsided, the sky rained burning embers, endangering nearby ships. Swiftsure’s tops received relatively minor damage, but fires broke out on Franklin and Alexander. It took two hours for the crew of the latter to put out the fire.

As if mesmerized by the terror of the explosion, both sides ceased fire and did what they could to rescue survivors. While tattered and terrified men bobbed about the bay and called for help, British vessels sent out longboats to rescue the perishing French. Desperately clinging to anything that would float, the survivors were a pathetic sight.

Many were injured and burnt, others had literally had their clothing ripped off by the tremendous force of the blast. Some British sailors shared their own clothing with the wretched survivors. The explosion of Orient had been a holocaust. From a crew of 800, British rescue boats saved no more than 70 men.

As rescue efforts subsided, the battle slowly resumed. The fighting was centered around Franklin, whose resolute crew refused to give in. Freed to seek other targets following the destruction of Orient, Nelson’s fleet closed in for another kill. The Chevalier de Blanquet reported that Franklin was “surrounded by enemy ships, some of which were within pistol shot, and who mowed down the men with every broadside.” By 11:30 p.m., the French ship had lost her main and mizzen masts as well as a staggering two-thirds of her crew. Down to just three functioning guns, the crew of Franklin finally struck their colors.

Nelson hoped to complete the destruction of the French fleet, but his own ships were scattered and disorganized after hours of heavy fighting. The French fleet was in even worse condition, with a dwindling number of ships still capable of action. Heureuse, Mercure, and Artemese had all run aground, sitting ducks for renewed attacks. Ball started up a fresh duel with Tonnant, battering the already weakened ship. Rather than surrender, the French crew cut their anchor cable and ran toward shore, likewise running aground. Theseus and Alexander ventured as close to the shallows as they dared and lobbed fire toward the stranded and helpless French ships.

By dawn of August 2, after a brief period of rest and repairs, British ships rallied for a renewed push against what was left of the enemy fleet. The French rear, which had remained inexplicably detached from the fighting, was still unscathed, and consisted of three ships-of-the-line, Guillaume Tell, Genereux, and Timoleon, as well as the frigates Diane and Justice. Eventually five British vessels, the Theseus, Alexander, Majestic, Leander, and Goliath, crowded around the ships of the French rear and opened fire.

Fighting spirit, however, was clearly gone from the demoralized French, and the commander of the French rear, Rear Admiral Pierre-Charles de Villeneuve, wisely opted to disengage and make a run for it with his remaining ships.

As the French fled, misfortune struck yet again. Timoleon had taken a severe pounding from the attacking British, and was left with damaged masts, sails, and rudders. Running aground in the confusion, the vessel was helplessly immobilized. Captain Louis-Leonce Trullet would refuse to surrender, choosing instead to abandon ship and burn his vessel rather than turn it over to the British. Of the once-great French fleet, Villeneuve escaped with just four vessels: two ships-of-the-line and two frigates.

Following Villeneuve’s escape, the British fleet was left the undisputed master of Aboukir Bay. As the frenetic pace of the battle subsided, the full magnitude of the victory became apparent. The bay presented a shocking scene of smoke, death, and destruction. The French Republic’s grand fleet had been wrecked. The British had captured or destroyed 11 ships-of-the-line, two frigates, and one brig in one of the most remarkably one-sided victories in British naval history.

The Battle of Aboukir Bay, or the Nile, as it also came to be known, was costly to both sides. British losses amounted to 895 killed and wounded; the hard-fighting Bellerophon alone suffered nearly 200 casualties. The destruction of the French fleet was so complete that precise casualty figures remain elusive. Estimates ran as high as 6,250 total in killed, wounded, and missing; the number included 3,305 French prisoners. Naval surgeons worked for days, treating ghastly wounds and amputating horribly mangled limbs.

For his part, Nelson was exultant at the scale of his success. “Victory,” he would write, “is certainly not a name strong enough for such a scene as I have passed.” Although such grand sentiments were certainly cold comfort for the common sailors who had bled and died at Aboukir Bay, the strategic victory wrought at the battle was truly epic in proportion.

Most importantly, Britain was once again the undisputed master of the Mediterranean, and Napoleon’s grand scheme for menacing Egypt and India were inevitably doomed to failure. Without the support of a strong fleet that could facilitate resupply and reinforcement, the ambitious French adventure in Egypt died with a whimper. Entirely cut off and left to its own devices, the French expeditionary force suffered final defeat and dissolution by 1799.

For the great victory at the Nile that saved the farthest reaches of the British Empire, Nelson would become an unparalleled legend in the pantheon of British national heroes. He was likewise destined for immortality, and an early grave, for his victory over a combined French and Spanish fleet at Trafalgar in 1805.

In a letter to his father after the Battle of the Nile, an exultant Nelson nonetheless refused to take credit. “It was not in the power of man to gain such a victory,” he wrote, “the hand of God was visibly pressed on the French.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments