By Eric T. Baker

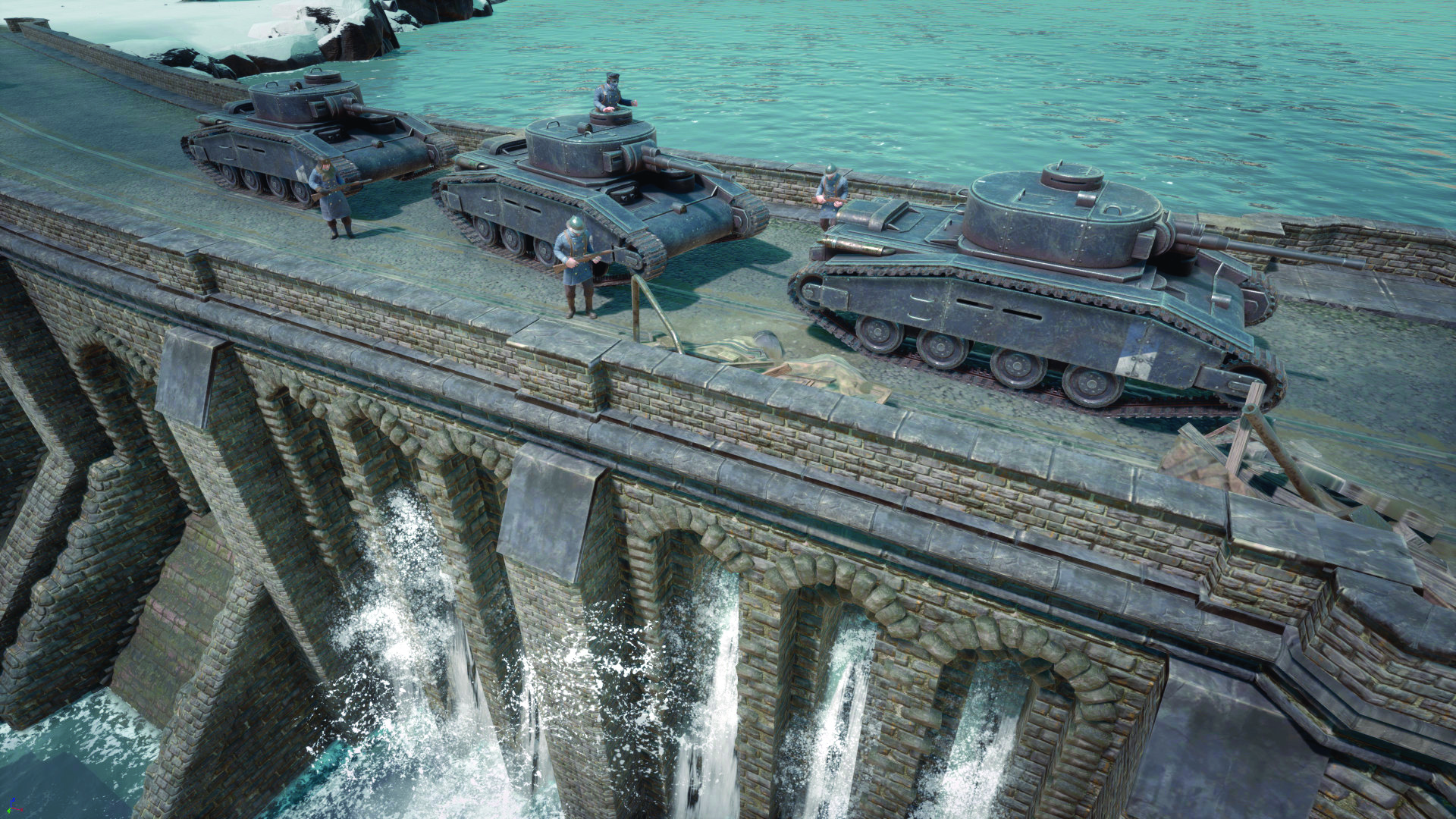

Sid Meier’s Civilization IV is the preeminent strategy video game in the world. It optimizes all of the best features of the previous incarnations of the game and weds them to gameplay that was designed from the beginning to include multiplayer options. The only way to make it better was to add more to it, including spicing up its combat, and that is exactly what the first expansion to the game, Civilization IV: Warlords, does. The expansion includes new scenarios, new civilizations, new units, and new leaders as well as rules for vassal states. Yes, other civilizations can now be conquered instead of having to be wiped out.

Despite the expansion’s name, warlords do not make the biggest change in the game, but they do round out the roster of great people that civilizations use for the extra abilities that differentiate them from each other. Warlords can increase the military potential of cities or be sacrificed to create academies or sent into the field to give bonuses to the troops they are stacked with. Warlords are not, as in some games, troops unto themselves and if sent out to fight, they are best stacked with the player’s most invulnerable army.

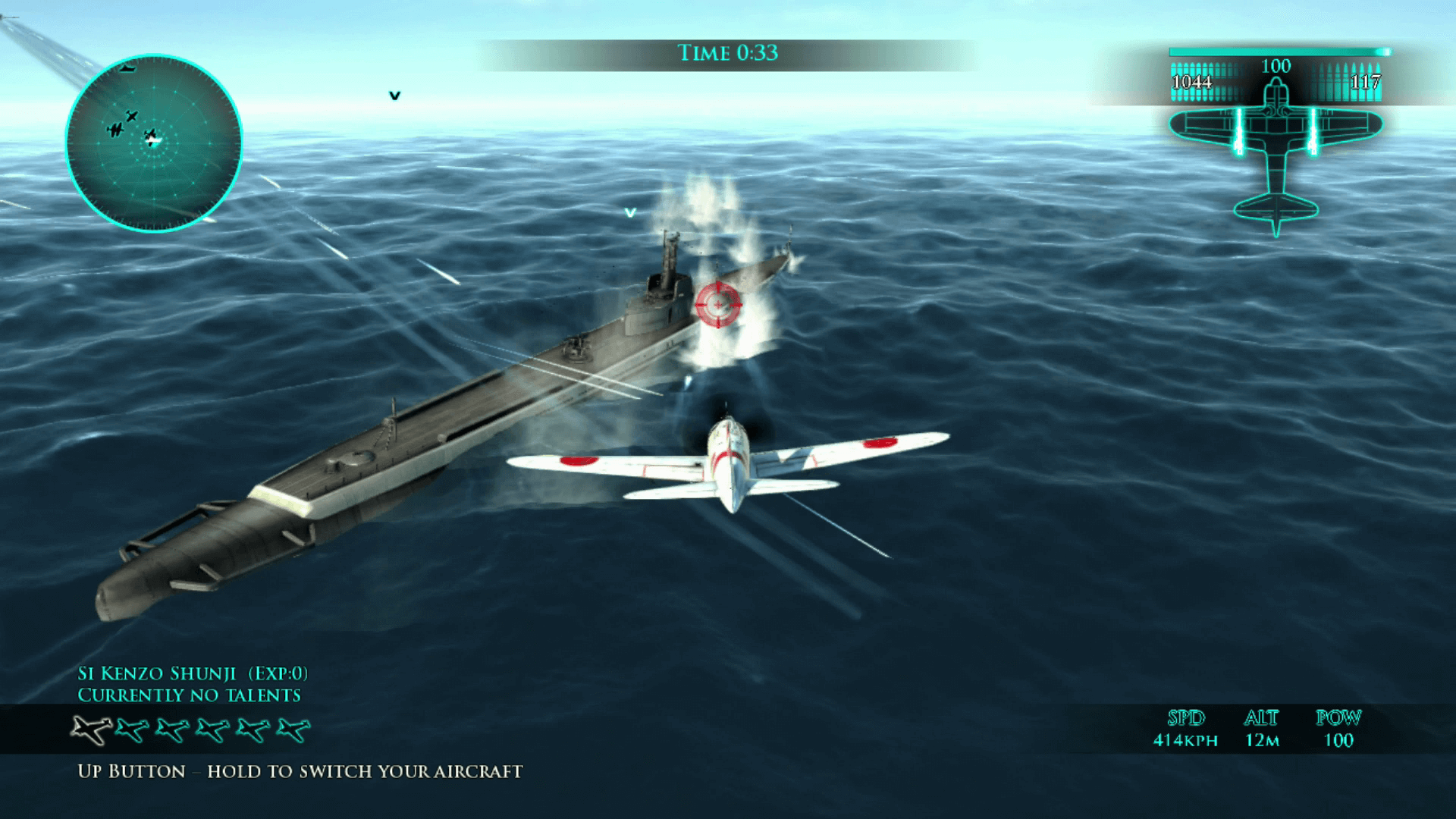

A video game on a more tactical level is Sierra’s Joint Task Force, a squad-based anti-terrorist game. The players take command of a special multinational quick- response force tasked with battling terrorists and guerrillas around the globe. Players start with a basic squad and basic weapons and over the 20 single-player scenarios build up the numbers, experience, ability, and equipment of their men. The interface is third person in the style of an RTS game, but there is no factory building or resource capture. Instead, the player tries to complete the scenarios as quickly and cleanly as possible, earning good press with the world’s news organizations that translates into more money that can be spent on improving forces.

Included in JTF is the mechanic of heroes. Players start with one hero and by earning experience with their other men can create more. Heroes are the focus of the command rules, can learn special skills, and are the unit that can call in reinforcements and air strikes.

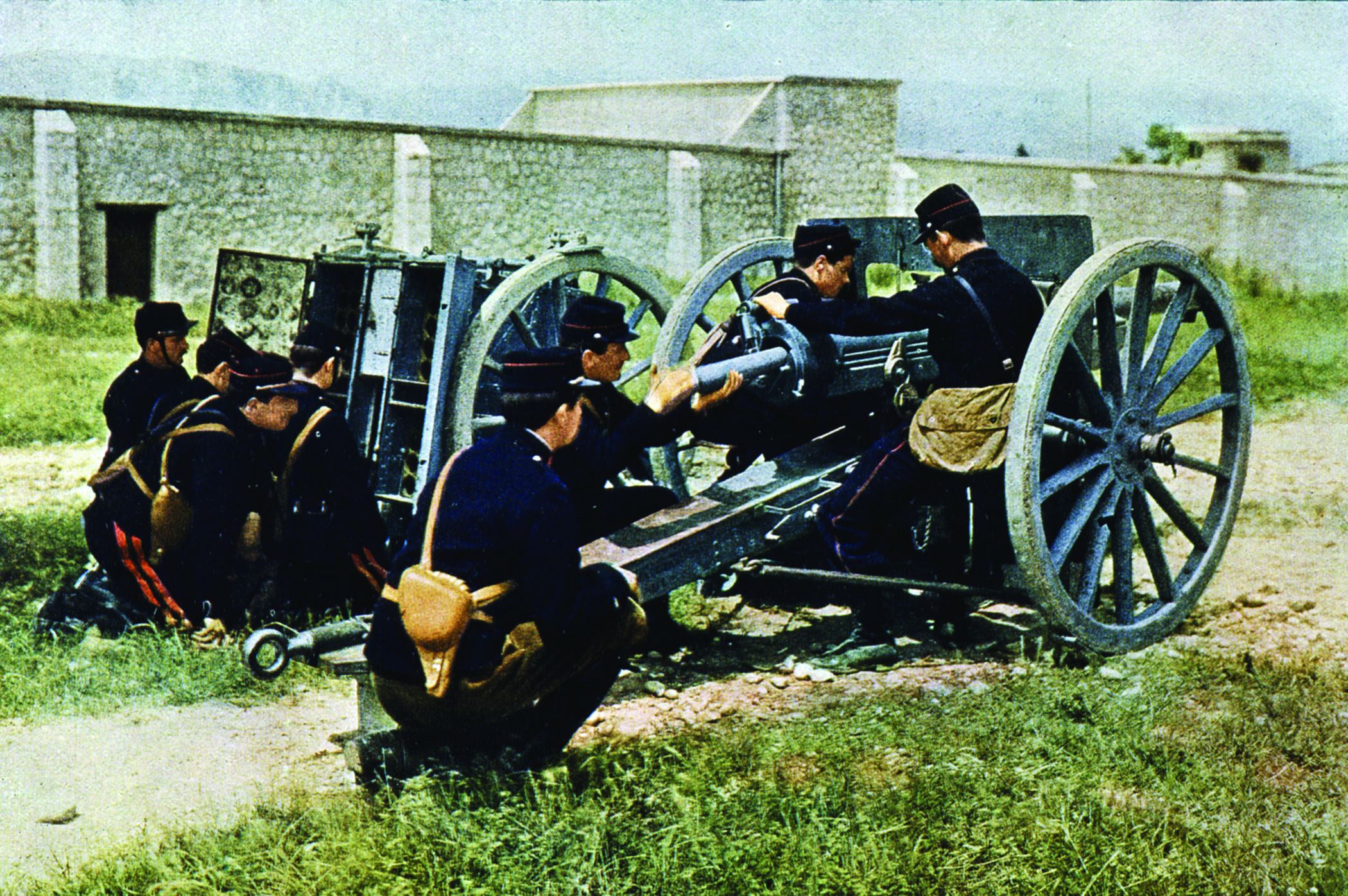

The current renaissance in board games includes a lot of tabletop games that model classic military conflicts in ways other than just hexes and counters. One of these games is Commands and Colors: Ancients, which lets players fight 13 different battle from 3000 bc to 400 ad using a basic map with terrain overlays to change it from battle to battle, labeled wooden blocks for units, 60 “command” cards, two player aid cards, and 7 “battle” dice.

The scale of C&C:A varies with each battle. In the oldest battles a unit can represent a few men, while in later battles a counter might stand for a whole legion. Fog and fortunes of war are handled by the command cards, while the actual resolution of clashes turns on the dice. The game mechanics are simple, but they reward the same things that more complex systems do: knowing the capabilities of the troops, using terrain to advantage, and being able to adapt to the battle as it happens.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments