By Mason B. Webb

The six-month-long land and naval battles for Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands chain have been well covered in books and magazine articles, but the war in the skies above the islands has received less attention.

In his outstanding autobiography The Guadalcanal Air War: Col. Jefferson DeBlanc’s Story (Pelican, Gretna, LA, 2008, 240 pp., maps, hardcover, $24.95), Jefferson DeBlanc makes up for that deficiency and describes the tremendous aerial battles that tipped the scales of victory to the American side. Despite the fact that, as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve, DeBlanc had limited experience in the Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter, he was assigned to the VMF-112 Marine Corps squadron as a Wildcat pilot in the Solomon Islands in November 1942.

On his first day in combat with the VMF-112 “Wolfpack,” he and a wingman shot down two Japanese Mitsubishi “Betty” bombers. He was promoted to second in command of his squadron the next day and promptly shot down two Japanese fighters.

VMF-112 pilots soon traded in their Wildcats for the more powerful Vought F4U Corsairs and began wreaking havoc among enemy formations. At the end of January 1943, DeBlanc was leading the squadron and downed five enemy planes in one day before he was forced to bail out of his own crippled aircraft over the water.

DeBlanc describes the tense moment: “After bailing out of my stricken fighter, I had unfortunately reacted too quickly. Instead of free-falling at least 1,000 feet, clear of the dogfight arena, I found myself in the same sky with the Zeros! Helplessly exposed, I decided to play dead, just like the possums in Louisiana would do. I let myself go limp, with head sagging, as the Japanese pilot circled me twice.” The enemy pilot flew off, evidently convinced that DeBlanc was dead.

Rescued by native coastwatchers and disguised in a Japanese uniform, he managed to evade the enemy and eventually returned to duty, where he resumed his fight against the foe. For his extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty, DeBlanc was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Sadly, Colonel DeBlanc passed away before the publication of his memoirs. But, thanks to his well-written book, the memories of the deeds that he and his fellow Marine airmen performed will never die.

Through Blue Skies to Hell: America’s “Bloody 100th” in the Air War Over Germany, by Edward M. Sion, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, 220 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, maps, hardcover, $32.95.

Through Blue Skies to Hell: America’s “Bloody 100th” in the Air War Over Germany, by Edward M. Sion, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, 220 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, maps, hardcover, $32.95.

Ed Sion has done an excellent job in chronicling the combat exploits of his uncle, Dick Ayesh, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombardier who served with the 100th Bombardment Group. Using his uncle’s wartime diary as the basis for his story, Sion paints an unerringly accurate picture of what life and death were like for the young men of the Eighth Air Force who braved enemy flak and fighters to bomb German targets.

Sion’s uncle wrote: “Anyone who has really been in combat will tell you––most of what went on was very uncoordinated. Everybody was scared to hell. If you talk to anybody who has really been in combat, there are no heroes. You just do your thing and pray that you don’t get hurt or killed or shot or anything like that. By the grace of God you got through. Anyone who was in combat knows that. Early in the war, only one out of three airmen survived. Then later, with fighter escorts, two out of three survived. That made me feel better. I’ll take those odds any day.”

Sion covers the air war and all its many facets as seen by the 100th Bomb Group––everything from recruitment to training, deployment, formations, tactics, life at an English airfield, the crews’ off-duty time, and the fearful hours going to, from, and over the target.

For anyone who wants to know more about what being a part of a bomber crew was all about, it will be hard to find a better book on the topic than Through Blue Skies to Hell.

Hell Hawks! The Untold Story of the American Fliers Who Savaged Hitler’s Wehrmacht, by Robert F. Dorr and Thomas D. Jones, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, 336 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, maps, hardcover, $24.95.

Hell Hawks! The Untold Story of the American Fliers Who Savaged Hitler’s Wehrmacht, by Robert F. Dorr and Thomas D. Jones, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, 336 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, maps, hardcover, $24.95.

Formed and activated in 1943, the 365th Fighter Group, dubbed the “Hell Hawks,” has a legacy unlike any other group of aviators to take to the skies during World War II. Most of the group’s pilots were barely 20 years old and fresh from pilot training when they were suddenly thrust into the deadly aerial war above Europe.

Shortly before the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944, the Hell Hawks, flying the big, heavy Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter, achieved air superiority, softened up the enemy, and then flew in close support of Eisenhower’s ground forces as Allied infantry and armor spread across the French landscape.

The men of the 365th took part in a variety of missions––1,241 missions, to be exact–– everything from escorting bombers to dueling with enemy fighters and attacking German infantry and installations to cremating American war dead on foreign soil. During their year in combat, the Hell Hawks’ contribution came at a heavy price; 69 of their number died in the battles for the sky.

Hells Hawks! is a fascinating, superbly written, and detailed account of the realities and terrors of combat flying and will be a welcome addition to any air war buff’s book collection.

American Bomber Crewman, 1941-45, by Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Osprey Press, Botley Oxford, UK, 64 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, illustrations, maps, softcover, $18.95.

American Bomber Crewman, 1941-45, by Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Osprey Press, Botley Oxford, UK, 64 pp., bibliography, index, photographs, illustrations, maps, softcover, $18.95.

Fremont-Barnes presents a concise, jam-packed book about American flight and ground crews in England and in the skies over enemy-held territory. He outlines the recruitment, training, uniforms, and equipment of the Yank fliers and their ground-bound maintenance men, then goes into the details of their daily lives, both in combat and while standing down between missions.

The author also soberly reminds readers that England-based bomber crews had the highest casualty rates of any U.S. arm of service during the war. As he writes, “Some men managed to survive all 25 combat missions, after which they could re-enlist or receive an honorable discharge and return home. Others were unfortunate to be killed on the first one, like radioman Charley Gunn, for whom a cablegram was waiting back at his base informing him of the birth of his son.”

The book also includes a compendium of museums and USAAF-related collections in the U.K. and U.S., ideal information for anyone wanting to learn more about the bomber crews —a brief but outstanding and informative book about these gallant men.

Griffon Spitfire Aces, by Andrew Thomas, Osprey, Botley Oxford, UK, 2008, 96 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, softcover, $22.95.

Griffon Spitfire Aces, by Andrew Thomas, Osprey, Botley Oxford, UK, 2008, 96 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, softcover, $22.95.

The Griffon-powered Supermarine Spitfire XIV is considered by many to be the best low-level fighter of World War II. When Hitler launched his V-1 “buzz bomb” assault on Britain, the Royal Air Force moved Spitfire squadrons close to the coast to dispatch them against the flying bombs. Using a daring and highly dangerous technique of flying alongside the V-1s, the Spitfire pilots would tip the enemy’s pilotless missile over with the aircraft’s wingtip to throw it off course.

But tipping “Doodlebugs” was not the Griffon Spitfire’s only mission. The aircraft proved itself to be an outstanding weapon in the heavy air battles during the campaign in western Europe in aerial assaults against German air and ground targets. No less a figure than Adolf Galland, the former Inspector General of the Luftwaffe, hinted at the aircraft’s effectiveness when he said, “The best thing about the Spitfire Mk XIV was that there were so few of them.”

The aircraft, according to the author (who is currently on active duty with the RAF), also played major roles after the war in the conflicts in Malaya and Palestine. First-hand stories from the cockpit, previously unseen photographs, and profiles of Spitfire aces complete this account of the most powerful Spitfire variant ever built.

The Flying Greek: An Immigrant Fighter Ace’s WWII Odyssey with the RAF, USAAF, and French Resistance, by Colonel Steve N. Pisanos, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 349 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $34.95.

The Flying Greek: An Immigrant Fighter Ace’s WWII Odyssey with the RAF, USAAF, and French Resistance, by Colonel Steve N. Pisanos, Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 349 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $34.95.

If he did not have the photos and documentation to prove it, a reader could be excused for thinking that Steve Pisanos’s The Flying Greek was all just some highly romanticized work of derring-do fiction. Yet, Pisanos’s tale, incredible though it may seem, is true.

Born in Athens, Greece, in 1919, Spyridon “Steve” Pisanos acquired an early love of aviation. Unable to gain admittance to the Greek Air Force Academy and having no money for private flying lessons, in 1939, assuming that he would have a better chance of learning to fly in the U.S., he got a job as a seaman on a cargo ship heading to America. Once he reached New York, he found a job and an apartment, began learning English. and took flying lessons. After the war broke out, Pisanos joined not the USAAF, but the RAF, and headed back across the Atlantic to fly and fight for the 71 Eagle Squadron, made up of American volunteer pilots.

In 1942, the Eagle Squadrons were transferred to the USAAF. Pisanos became a naturalized U.S. citizen while in London and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He then flew numerous missions in Spitfires, P-47s, and P-51s. After his 10th confirmed kill, he crash-landed his P-51 in France and spent six months with the French Resistance, evading capture.

After the war, he was returned to the States and became a test pilot. He enjoyed flying so much that he made a career out of it, spending 30 years in the U.S. Air Force, taking part in three wars, and retiring as a colonel. The Flying Greek is a riveting, remarkable account of one man’s love of flying and of his adopted country.

Finding a Fallen Hero: The Death of a Ball Turret Gunner, by Bob Korkuc, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2008, 256 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Finding a Fallen Hero: The Death of a Ball Turret Gunner, by Bob Korkuc, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 2008, 256 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Combat aviation, as everyone knows, is a dangerous and often deadly occupation. The U.S. Eighth, Ninth, Eleventh, Twelfth, and Fifteenth Air Forces, based in England and the Mediterranean, suffered horrendous casualties due to accidents and battle losses during World War II. It is estimated that some 30,000 air crewmen in the European and Mediterranean Theaters lost their lives, while more than 13,000 were wounded. Approximatley 51,000 were taken prisoner or were listed as missing.

One of the most dangerous positions on a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber was that of ball turret gunner. The crewman filling that position would curl up in a small, spherical chamber that hung below the belly of the aircraft, his knees up around his ears, and then swivel the ball and its machine gun 360 degrees to ward off enemy fighters that might be attacking from below. In case of emergency, the ball turret gunner usually had the least likely chance of getting out.

On February 25, 1944, ball turret gunner Anthony Korkuc, the uncle of the author of Finding a Fallen Hero, was killed when his B-17 was shot down over Germany. In 1995, his nephew, Bob Korkuc set out on a seven-year quest to find out exactly what happened to his uncle Tony. That journey is recounted in this very moving book. The author interviewed everyone he could find who knew his uncle and even went to the place in Germany where the B-17 crashed due to antiaircraft fire and interviewed townsfolk who were there on that fateful day.

In meeting one of the witnesses, Korkuc was handed a small cardboard box. “As Marcus translated Hermann’s words,” Korkuc writes, “I learned that the box contained artifacts removed from the crash site, including two rusted and mutilated .50-caliber shell casings and a .50-caliber bullet. There were also pieces of Flying Fortress 42-37786. It was possible that Tony Korkuc had fired the gunner’s shells that were now in my hands. I was touching a special piece of my uncle’s history.”

Finding a Fallen Hero is a healing chronicle that will strike a chord with any reader who has lost a family member to war and will inspire others to satisfy their own unanswered questions.

Short Bursts

Easy Company Soldier: The Legendary Battles of a Sergeant from World War II’s “Band of Brothers,” by Don Malarkey (with Bob Welch), St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2008, 277 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Easy Company Soldier: The Legendary Battles of a Sergeant from World War II’s “Band of Brothers,” by Don Malarkey (with Bob Welch), St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2008, 277 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Anyone familiar with Band of Brothers, the Stephen Ambrose book and HBO series of the same title, will immediately recognize the name Don Malarkey, and the former airborne trooper has finally penned his autobiography.

Malarkey’s exploits as a member of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division make for heart-pounding reading. He traces his life from his boyhood in Astoria, Oregon, a time of hard work, decent values, and fierce patriotism.

Although he had flunked the Marine Corps physical, Malarkey decided to join the paratroops shortly after war broke out. Dropping out of college, he was assigned to the 506th PIR and survived the legendary hell of Captain Herbert Sobel and the training at Camp Toccoa, Georgia.

In September 1943, the division arrived in England and began training for D-Day, nine months into the future. Malarkey recounts those months, plus all the combat that followed: the jump into Normandy, the battle for Carentan, the Holland jump (Operation Market-Garden), the frozen hell of Bastogne and the Bulge, and into Austria when the war ended.

After the war, he fought another battle––the battle of the bottle. Feeling his life going down the drain and contemplating suicide, he managed to shake himself out of his funk and remembered all the combat he had seen and all the times when he could have given up and did not. He managed to get his life back on track and even served as a consultant for the HBO series.

Malarkey’s autobiography is a tender story by a tough soldier. Not to be missed.

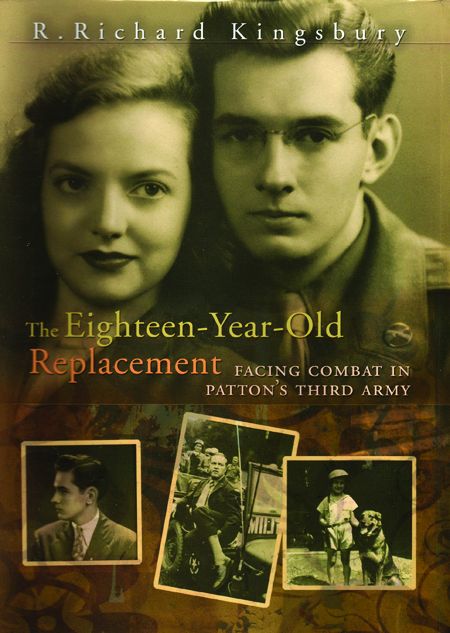

The Eighteen-Year-Old Replacement: Facing Combat in Patton’s Third Army, by R. Richard Kingsbury, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2008, 277 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $24.95.

The Eighteen-Year-Old Replacement: Facing Combat in Patton’s Third Army, by R. Richard Kingsbury, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2008, 277 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $24.95.

When the U.S. entered World War II, 18-year-old enlistees were routinely not sent into battle until they turned 19. But as casualties mounted, more and more younger men were sent to the front lines as replacements.

Laced throughout with self-deprecating humor, Kingsbury’s book recounts how he was thrust into the fighting along the Siegfried Line with the 94th Infantry Division. His well-written memoir provides a touching portrait of what he endured both physically and emotionally and tells how he went from boyhood to manhood almost overnight, nearly losing his life when wounded at Ludwigshafen.

The Eighteen-Year-Old Replacement is as fine a first-person account of war as will be found anywhere.

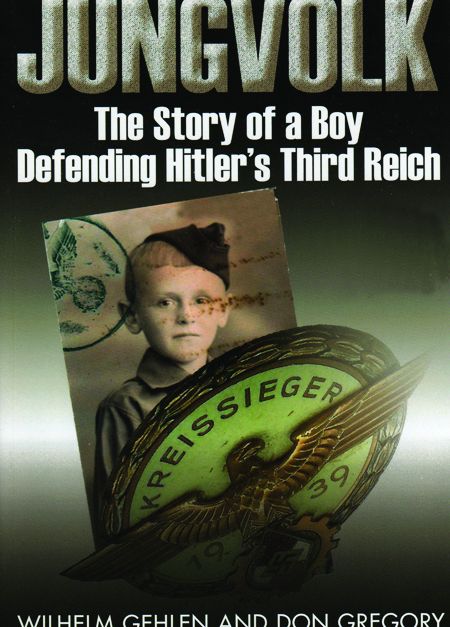

Jungvolk: The Story of a Boy Defending Hitler’s Third Reich, by Wilhelm Gehlen and Don Gregory, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2008, 318 pp., photographs, softcover, $24.95.

Jungvolk: The Story of a Boy Defending Hitler’s Third Reich, by Wilhelm Gehlen and Don Gregory, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2008, 318 pp., photographs, softcover, $24.95.

The story of the Hitler Youth organization is one that has not received much notice in the U.S., and the Jungvolk even less. The Jungvolk was a branch of the larger Hitler Youth created especially for boys ages 10 to 14.

The Hitlerjugend (HJ) or Hitler Youth organization, under Baldur von Shirach, was a nationwide group designed to indoctrinate German boys into the Nazi way of life, give youngsters basic lessons in the military, and also to provide volunteer workers for various community projects. These included collecting scrap and battling pests that could ravage German crops. Some HJ and Jungvolk units also served as messengers for antiaircraft batteries.

As the author says, “To the reader it might seem rather amazing and unbelievable that the Nazis required children to do their bit for so-called ‘Fuhrer, Volk, und Vaterland,’ and work toward a final victory for Germany, but that is exactly what happened.”

Gehlen goes on to detail the operation of the HJ and Jungvolk organizations and the small part he played in them. This is a truly fascinating study of a young boy’s life under the swastika.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments