By Alan Davidge

Known throughout France as the Village des Martyrs—“Village of Martyrs,”—the pillaged remains of Oradour-sur-Glane have stood nearly eight decades now as a memorial to the dead and reminder of the atrocities of war. Everything has been kept as it was on June 10, 1944 when some 642 men, women and children were shot and burned to death. The places of execution and other points of significance where the nearly 600 unidentifiable bodies were found, are respectfully signposted.

A sign at the entrance, in English, says simply: “Remember.”

Marguerite Rouffanche, 46, her two daughters and grandson, were among the 250 women and 200 children packed into the church as a group of young men in SS uniforms carried a heavy box and placed it in front of the high altar. Soon after the men locked the front door, the box exploded with an almighty roar, shooting debris throughout the church. It blew out the stained-glass windows and filled the sanctuary with suffocating smoke.

Those who were still mobile, headed for any source of fresh air. Their pressure on the sacristy door to the left of the altar caused it to give way and provided some temporary relief—but not for long.

Soldiers waiting outside then burst through the main doors and opened fire at anyone still standing. Through the sacristy windows came a further hail of bullets, one of them mortally wounding Andrée, Marguerite’s married daughter, in the throat. As bodies fell around her, Marguerite dropped and feigned her own demise. Further firing from the basement of the sacristy and grenades thrown through the shattered windows attempted to finish off the survivors.

As Marguerite lay in purgatory among the dead and dying, straw and other combustible material was thrown over the bodies and set alight. Her second daughter, Amélie, was one of those consumed in the inferno. The confusion created by more smoke and flames gave Marguerite a chance to make a move. She crept behind the altar and considered her options. A short ladder used for accessing the church candles was within reach and a few seconds later she was on her way out of the largest of the damaged windows behind the altar.

Marguerite jumped 10 feet into the brambles below and, hearing a voice from behind, saw her friend Mme Joyeux, with her seven-month-old baby, Réné, climbing out behind her. She cried out for Marguerite to catch Réné, threw him to her, and leapt out herself. The baby’s cries alerted German soldiers stationed on the road opposite who turned round and shot the mother and her child.

Marguerite launched herself forward to take cover in the rectory garden next door, but before she hit the ground, she had taken five rounds herself. Believing that was enough to dispatch anyone, the soldiers left her for dead.

Slowly and painfully, with a smashed shoulder and four leg wounds, she crawled into the rectory garden where she was rescued by friends the following afternoon. Marguerite was later to discover that she alone had survived out of all the 453 women and children who had been herded into the church of Saint Martin in Oradour-sur-Glane, to be bombed, shot, or burned to death on the afternoon of June 10, 1944.

Prior to June 1944, the town had not been directly affected by the war. Many of its menfolk had suffered the horrors of 1914-18 and a memorial in the church reminded its congregation of the names of 101 men who hadn’t returned. But after the signing of the armistice with Germany on June 21, 1940, Oradour found itself in the relative peace of the Unoccupied Zone, subject to the puppet government installed by Germany in the central French town of Vichy.

Unlike Paris and the towns on the Normandy coast, there was little in the area of strategic interest for the Führer, and there was no history of Résistance activity or provocation of the Germans. In fact, the last time a German had been seen in Oradour was in late 1942.

Those who lived there in 1944 saw few visitors during the week except for the regulars who traveled via the tram service from the nearby city of Limoges, which began in 1911. Adults used the service to commute; for teenagers, it was the chance to meet up and enjoy liaisons in the evening before returning home.

During the last week in August, the annual festival took place. The fairground in the center of town was set up for roundabouts, stalls, and other amusements which were eagerly anticipated by members of all generations.

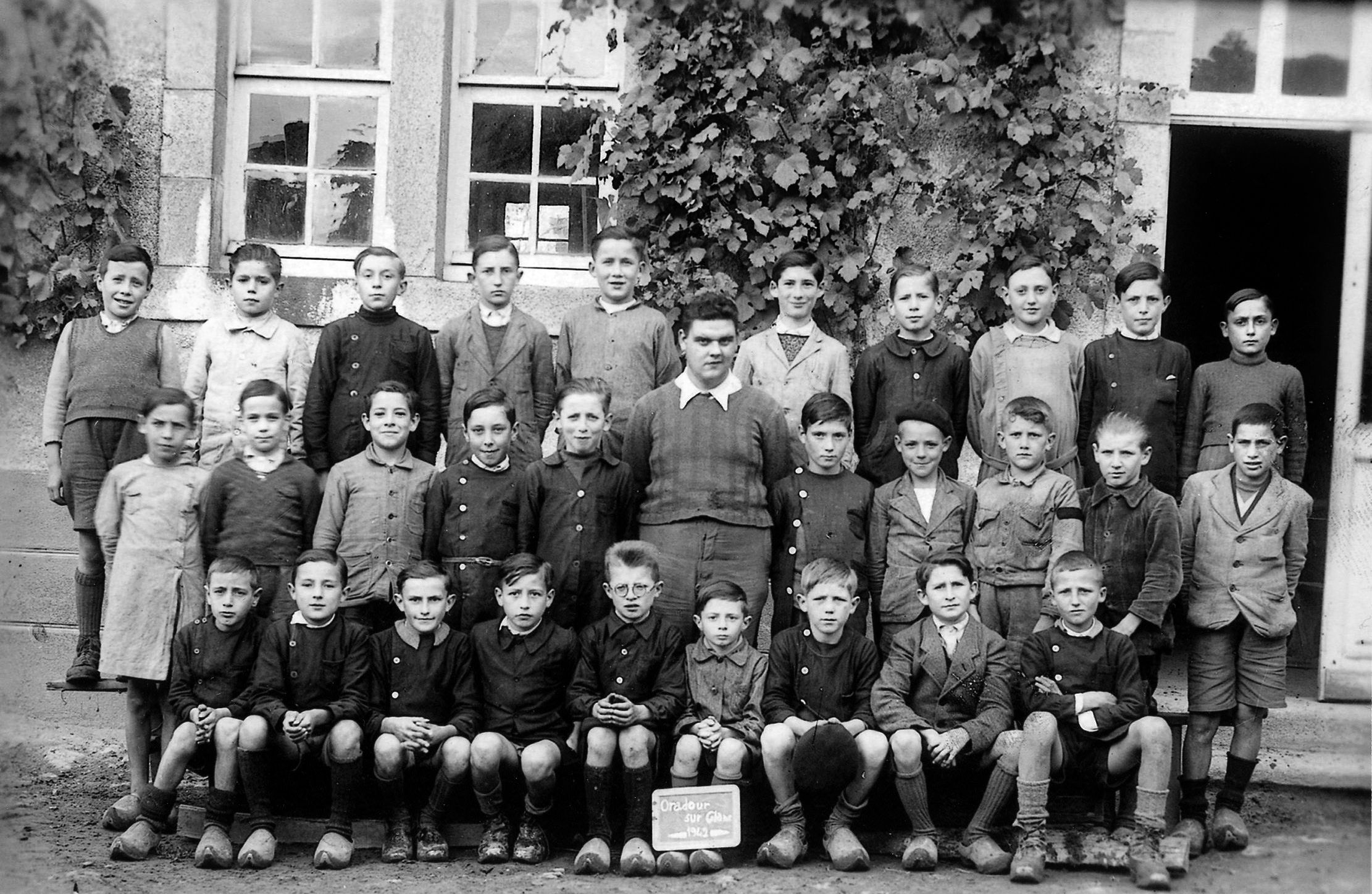

Daily life was predictable and peaceful in Oradour-sur-Glane. Only about a quarter of its 1,500 residents lived in the town. The rest were in outlying hamlets and farms. Oradour was well appointed with shops, restaurants, garages, and cafés that provided a chance for local workers to meet and exchange gossip after work or during their long lunch breaks. For the children, there was a boys’ school near the tram station, a girls’ school in the center, and a nursery school on the road out of town.

When the Germans had crossed the French border and occupied Alsace and Lorraine in 1940 (which they had lost in the post-WWI Treaty of Versailles), many of the locals fled to France; a small community of refugees from the Moselle area of Lorraine established themselves in Oradour. For their children, who brought with them their own teacher, Monsieur Gougeon, a special school of their own was established.

The Alsatians and Lorrains were largely welcomed, as were the Jews and Spaniards who had sought refuge from conflict elsewhere, but the complicated status of Alsace and Lorraine created waves that continued to reverberate across France.

Located on the eastern French border, the area had been seized by Germany from France at the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, and then France took it back after 1918. This was a predictable move politically but confusing and tiresome for the inhabitants, some of whom aligned themselves with France and others with Germany.

Most spoke Alsatian as their first language, which is more akin to German. More sinister was the fact that, once it was “liberated” again by Germany in 1940, the male population who had not fled could be pressed to serve in the German army, with their loyalties tested to the limit. Those conscripted became known as “malgré nous,” a French phrase literally translated as “in spite of us” and signifying that they were wearing German uniforms despite being French.

The SS Division “Das Reich” was one unit which drafted Alsatians into its ranks. It had suffered serious casualties on the Eastern Front in 1943, and began to make up its numbers from countries that Germany had conquered and occupied. The division had a tough and brutal reputation and was already responsible for several civilian atrocities, such as Kharkov in the Ukraine, which they left in flames in early 1943 with civilians hanging from balconies.

The division was moved to Montauban in southwestern France in April 1944 under a new commander, General Heinz Lammerding, a personal friend of Heinrich Himmler, with a fearsome reputation of his own. His task was to bring the division up to fighting strength and deal with Résistance activity in the area. New recruits, including those from Alsace, would, in turn, have to be brought up to the same ruthless standards or suffer severe punishment themselves.

The key personnel in this division of 18,000 men who were subsequently to play leading roles on June 10 at Oradour-sur-Glane included Colonel Sylvester Stadler, responsible for the Der Führer Regiment; the Kommandant Major Adolf Diekmann, in charge of its 1st Battalion; and Captain Otto Kahn, who led its Third Company with his deputy 2nd Lt. Heinz Barth.

During the time they were stationed down in Montauban, the Das Reich Division seized every opportunity to terrorize the population and execute Résistance members. They were assisted in this by the Milice, the French secret police set up by the Vichy régime after the armistice with Germany to spy upon their fellow Frenchmen. (After the Germans were forced out of the zone, many of the Milice became victims of the same kind of rough justice themselves).

On June 5, General Lammerding persuaded his superiors to agree to a new repressive program which was similar to their actions against partisans on the Eastern Front. By punishing ordinary civilians for attacks on the German army by the Résistance, it was hoped to turn the population against them. For every German wounded, five civilians would be hanged and this figure would double for every German killed.

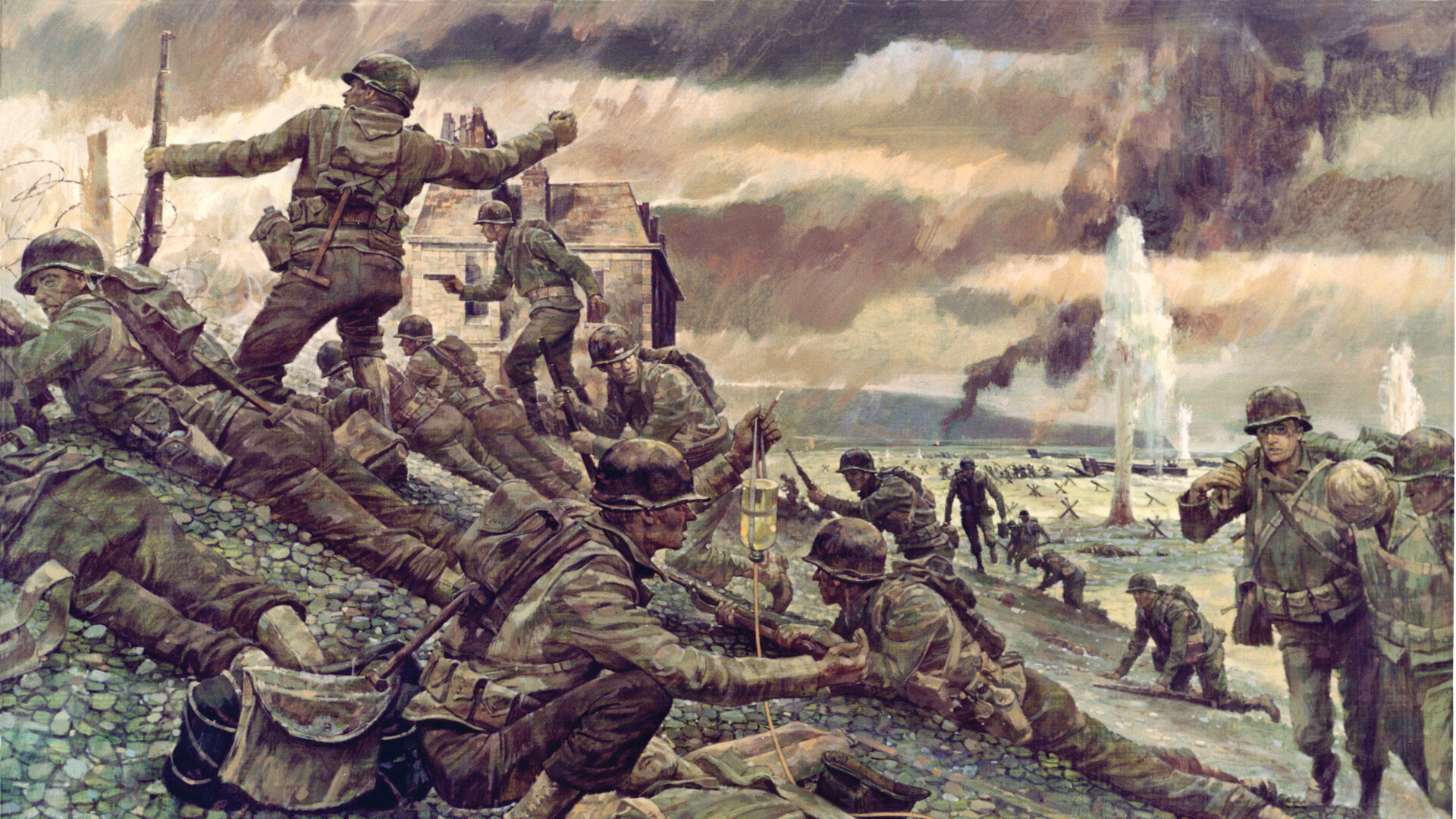

It was in Montauban that they heard the news of the D-Day landings in Normandy on June 6 and suddenly everything moved into a higher gear. The Résistants, emboldened by the belief that they would soon be liberated, began damaging railway tracks and lines of communications, often displaying too much bravado for their own good, but, having waited four years, this was understandable.

Many groups undertook selected attacks on the enemy. The Germans, in turn, carried out even more brutal reprisals. On June 8, the entire Das Reich Division was ordered north, initially to deal with Résistance activity in the area of Tulle (which had been temporarily liberated the day before) and the city of Limoges. They expected their ultimate destination to be Normandy to fight off the invaders.

Das Reich encountered hostility along the road but decided to make a stop at the small town of Rouffillac. At some point, Diekmann entered a bakery and asked a woman to make some crepes for him and his men. She refused. His response was to lock her and 15 others in the building and set fire to it. There was a skirmish with some résistants, and Diekmann continued north to Tulle. Here, on June 9, they met sustained opposition from the men who had liberated the town two days before.

Sadly, the French were outgunned and outnumbered, and over 100 were captured. Reprisals were swift and, by the end of the day, the Germans had executed 99 Frenchmen by hanging them on lampposts in the town. Das Reich was taking on the semblance of a mobile execution squad with a penchant for committing atrocities among civilians. Heaven help the people further along the road.

By the morning of June 10, Diekmann and his men had moved further northwest to the town of St. Junien, where he learned that his friend, Major Kämpfe, the officer in charge of a reconnaissance battalion, had been captured by the local Résistants. Diekmann met with his senior staff, the head of the Limoges Gestapo, and four members of the French Milice in the Station Hotel to plan their next move.

Even without the news that Kämpfe had been captured, it seems clear that a decision had already been made to undertake an operation that would teach the French a lesson and so shock the local communities that nobody would dare to make any further attacks on the division.

It is possible that the order came down from General Lammerding himself, but in the trial after the war Captain Otto Kahn, the officer in charge of the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of the Das Führer Regiment stated that it was Diekmann, his company commander, who had singled out Oradour-sur Glane as the target and appointed Kahn to take charge.

This would have come as no surprise to the more experienced soldiers in the regiment as atrocities such as this had been commonplace on the Eastern Front. Many of the men who had served in this campaign were now dead, and the challenge for Kahn was to produce similar results with their recent replacements. It would be a test of his mettle as well as that of his 3rd Company. His deputy, 2nd Lt. Heinz Barth, was heard to say “It’s going to heat up. Let’s see what the Alsatians are capable of .”

It may have been Oradour’s innocence rather than its complicity in recent events that resulted in its selection. There were no known Résistants in the town to cause a problem, it was easy to access and contain, and it was relatively affluent compared with its neighbors, which gave it some potential for looting.

The evidence for what took place next is largely dependent on the eye-witness accounts provided by a handful of survivors, and these have been pieced together in a generally accepted narrative. The German troops involved did their best to destroy any evidence, and those who were eventually brought to a war-crimes trial in 1953 could not be relied upon to tell the complete truth, as their lives depended on the outcome.

At about 1:45 p.m., Robert Hébras, a 19-year-old garage mechanic who worked most of the week in Limoges, was discussing the town’s next soccer match with his friend Martial Brissaud on the road outside his house in Oradour when two German halftracks appeared from the south road. This unnerved Martial, who had recently received conscription papers and ignored them, more than Robert, who regularly saw Germans in Limoges.

Martial took off in the direction of home, north of the town by a route off the beaten track and hid in the attic. (Robert Hébras is, at the time of this writing, 98-years-old and the last surviving survivor. He has devoted his life to narrating the events of June 10, 1944, and keeping alive the memory of his friends and neighbors.)

A small number of others also ran and hid that day, some successfully, when they saw the Germans, especially those who had escaped from POW camps or who today would be referred to as “draft dodgers,” knowing that capture by the SS could have very serious consequences.

The two halftracks had heralded the arrival of the 3rd Company of the 1st battalion, Der Führer Regiment of the Das Reich Panzer Division—around 200 in number. The remainder of the division was traveling northwards via other routes. Each of the two vehicles carried a dozen armed soldiers in camouflage uniform.

They headed north as if they were passing through the town, but a few minutes later they reappeared minus the troops who had occupied strategic positions to guard the roads out of Oradour, thus surrounding the town and preventing anyone from leaving.

Despite the fact that they hadn’t had any trouble with the Germans before, a number of people were suspicious of what was happening. Among them was Hubert Desorteaux, who owned the garage on the main road. He was able to hide in the corner of an unoccupied house nearby while other family members crawled into hen houses or sought shelter in the vegetable garden. Some were lucky enough to make it past the guards on the outskirts.

Martial Machefer, a local communist and already known to the Milice secret police, was stopped by a French-speaking (and probably Alsatian) German soldier to whom he showed his wounded veteran’s ID card and revealed his wounds from the Great War. In a rare display of compassion he was advised to make haste out of the town.

As the rest of the 3rd Battalion began to arrive in the town, Adolf Diekmann summoned the mayor, Dr. Desourteaux, father of Hubert the mechanic, and demanded that everyone assemble in a central place. The mayor then asked the town crier to announce this. The reason given was that it was a routine check on ID and papers.

Slowly, the townspeople began to collect in the fairground area, a place normally associated with much happier gatherings. Men were on one side, women on the other. They were hurried along by troops who marched into shops and houses, got everyone to stop what they were doing and hasten to join the swelling assembly, often with a rifle butt between the shoulders as an encouragement.

Men arrived from the barber’s shop half shaven, car repairs were cut short in the garages, children left schools with their lessons still on the blackboards and an anxious pastry chef expressed concern about his half-baked cakes. He was told they would be taken care of. The clocks were stopping in Oradour, and would be stopping forever.

This Saturday was a school day and arrangements had been made for a medical inspection. The town authorities were concerned that the privations of war should not interfere with their children’s health.

In the refugee school for children whose families had fled from Lorraine was seven-year-old Roger Godfrin and his two older sisters, neighbors of the Hébras family. Robert Hébras recalls little Roger’s mother always telling him to head for the woods and hide if he ever saw Germans.

Despite his age, Roger was a regular daredevil, an “enfant terrible” among his classmates. As the Germans started throwing their weight around, bullets began to hit the walls of the school and the teacher ordered everyone to take cover under their desks. When the situation worsened, Roger and his sisters ran outside to the infant school along the road.

The Germans then began ordering the children and teachers outside the school and Roger tried to convince his sisters to escape with him but they were too scared. Then, seeing the guard distracted by a teacher, he left the room and climbed out of a window. He intended to follow his mother’s instructions to the letter.

He had not run very far before he was shot at. He dropped to the ground and played dead. His assailant kicked him but he did not move. As soon as it was safe, he was up and running again but came face to face with another soldier. This one turned his back and told Roger to keep running. As he reached the riverbank, he was spotted by six men in a halftrack who opened fire, hitting a dog that had followed him but missing Roger.

This remarkable child then swam fully clothed across the River Glane to safety. On the other side, he was later picked up by a local road worker who took him to a house in a neighboring village for safety. (He was still there on Sunday evening when rescuers brought in Marguerite Rouffanche. Although badly wounded, she was able to tell him what had happened in the church and broke the news that none of his family had survived. Sadly, his mother would never know that her words of advice had saved her son’s life. (Roger lived till 2001 and was the sole survivor among the schoolchildren.)

After the forced evacuation of the schools, it started to get even nastier. The pregnant headmistress of the girls’ school, who was on sick leave, was forced out of her house in her pajamas to join the other women. Some isolated shots were heard but for the moment their origins were uncertain. It later became clear that, under orders, the troops were summarily dispatching anyone who was bedridden and could not leave their house. Then more halftracks appeared, carrying families from the outlying farms.

The assembly was completed about 2:45 p.m. The day had turned out to be a very hot one and the crowd was becoming uncomfortable. Diekmann’s next instructions were translated by an Alsatian SS soldier. They had been informed that there was a cache of arms and ammunition in Oradour and, if it was not found, the SS would begin setting fire to houses. Anyone who owned a weapon was asked to step forward. Nobody moved. They were peaceful people.

Getting no response, Diekmann then told the mayor to appoint 30 hostages, which he refused to do. Confident of his townspeople, M. Desourteaux then boldly offered himself and his family as hostages. This was treated with derision by the German kommandant.

At around 3 p.m., the women and children were led away from the rest of the group amid heartbreaking family farewells, taken to the church of St. Martin and locked inside. The men were then told that searches would be carried out and were given a final chance to say where the arms were hidden.

The request for ID and the suspicions about an arms cache made sense to everyone. They had heard how the Germans operated and were aware that in other local towns there were resistance cells and Maquis camps in the forest, but not in Oradour. They looked forward to being exonerated.

After an hour, the 180 adults and young men over 14 were divided up and taken to six separate, selected locations in the town. These were three barns: Laudy, Milord, and Bouchoule, plus the Denis wine cellar and the Desourteaux and Poutaraud garages. The size of the groups varied; the largest, about 60 in number, were assembled in the Laudy barn.

The men remained patient, confident in their innocence and refrained from making any false moves as the troops had set up machine guns pointing at them from the road outside. In the midst of this, at 3:40 p.m., a tram on a test run with three engineers from Limoges arrived. One of them stepped off and was promptly shot, his body thrown in the River Glane. The other two had their papers checked and were sent back to Limoges.

At about 4 p.m., Lieutenant Kahn discharged his automatic pistol into the air and the report echoed across the town. It was a signal. The machine guns, most likely the deadly MG 42s capable of firing 1,200 rounds per minute, that were leveled at the men of Oradour opened up in unison.

Marcel Darthout, one of the Laudy barn survivors remembered: “We heard the sound of a detonation coming from outside, followed by a burst of automatic weapons. In a few seconds I was covered with corpses and I heard the moans of the wounded. When the bursts had ceased, the Germans approached to exterminate us at point-blank range.”

He and another survivor confirmed that the first bursts were directed at their legs so there was no chance of rushing the guns or escaping. The last words that Robert Hébras heard from the father of his friend Martial Brissaud, who had lost a leg in WWI, was that the Germans had shot off his other leg. This fact was confirmed at the subsequent war-crimes trial by measuring the height of the bullet holes and the wounds of the victims.

While the atrocities were taking place, a group of seven cyclists from Limoges, having a day out in the summer sunshine, had the misfortune to arrive in Oradour. They were taken to the Beaulieu Forge, beside the barn of the same name where some of the executions took place. They, too, were gunned down. They had simply turned up in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Robert Hébras also found himself under a pile of bodies, getting soaked by their blood. He was uninjured until a soldier, patrolling through the victims and looking for sources of life that he could extinguish, finished off one of his friends and the bullet entered Robert’s arm. He could not afford to move, or he would be next. Hay and firewood were now being thrown on the bodies. Then he heard something totally bizarre: music. The Germans had found a radio and turned it on to accompany their killing spree!

This was cold-blooded, planned annihilation. The SS hadn’t been interested in their papers and had created this pretext and the story of the arms cache to facilitate rounding up the townspeople who in turn had accepted the inconvenience and expected to resume their daily activities as soon as the misunderstanding had been cleared up.

In each platoon there were a handful of men who did not take part in the executions. They ransacked the town, looting anything of value and drinking bottles of wine, beer, and brandy. They also collected poultry, pigs, sheep, and calves to feed the battalion. Once the execution of the men had been completed, buildings were systematically set on fire, which flushed out some of those who had successfully hidden from the Germans.

Others who lived in more isolated dwellings, having heard the commotion and anxious to collect their children from school, also appeared on the scene, and suffered the same fate.

Once the hay in the Laudy barn had been set alight, the Germans decided it was getting too hot to stay around, so they left to join in the looting of the town. Robert hung on as long as he could in the heat and smoke before crawling out of the carnage and was relieved to discover that the assassins had moved on. He ran through a small door that led into a yard but it was a dead end. He returned to the flames and found a way into a stable.

The sight of a shadow and the sound of voices brought fresh terror until he realized it was Marcel and three other people he knew: Matthieu Boris the stonemason; Yvon Roby; and Clément Broussadier. Most of them had bullet wounds in their arms or legs. They were still trapped but Matthieu used his skills to pick a hole through a wall, which allowed access to another section of the barn; he and Robert hid in a woodpile while the other three headed for the loft.

Two SS men appeared, and seizing an opportunity for further arson, set fire to the straw and the roof. Once again, Robert and his friends hung on until the heat forced them out into a yard. This was opposite the fairground road that was being patrolled, so they hid in the first of three vertical hen houses till it caught fire, moving along sequentially till the third was ablaze at about 7 p.m. and most of the Germans had disappeared.

As the evening passed, each member of this brotherhood forged in the heat of the Laudy barn made his bid for freedom—all except Marcel, who felt that his four bullet wounds would slow down his friends; he resigned himself to his fate and stayed put.

Yvon Roby and Clément Brossadier headed for the cemetery and the fields beyond with Clément getting wounded along the way. Not wanting to take any further chances, they spent the night in the open. Marcel’s selfless gesture paid off, as he was eventually rescued and able to give evidence at the war-crimes trial several years later, finally passing away peacefully at the age of 91. Like Robert Hébras, he devoted as much of his later years as possible to educating the world about Oradour.

Mathieu Borie suggested he would also try to make it to the cemetery and from there seek the cover of the woods. Robert followed him and together they continued beyond the trees into the safer realms of the outlying hamlets, found shelter and water to drink and did their best to explain to their horrified neighbors what had happened to their little hometown that was now ablaze and lighting up the evening sky.

A handful of others who had hidden before the fairground roundup managed to escape under cover of darkness but the sporadic gunfire heard after the mass executions suggested that the sentries were still in action. One of the unluckiest was garage owner Pierre-Henri Poutaraud, who had also escaped from the Laudy barn but whose bullet-riddled body was found the next day hanging on the fence by the cemetery.

There was to be no better news from the church, where Marguerite Rouffanche and all the other women and children had been incarcerated after being separated from their menfolk. Following the initial fire and explosion from which only she had been able to escape, one of the soldiers took a stack of explosives to the top of the tower which, when detonated, brought down the whole roof and created a fire fierce enough to melt the church bell (which still remains in a corner of the ruins as a testimony to the horrors in a church that had suddenly become a crematorium).

Ironically, one of the SS men who had placed the explosives in the church was unable to exit fast enough and was himself caught in the blast. Untersturmführer Knug was the sole German fatality at Oradour on June 10.

Around 6 p.m., Jean Pallier, a railway engineer on the way to Oradour in a truck, was stopped by guards 300 yards from the town. He was then joined by passengers from the Limoges tram. They were prevented from crossing the field to see what had happened in the town, which was now completely ablaze. After having their papers checked they were released and told, “You can say that you are lucky. The slaughter is over.”

There is evidence to suggest that Diekmann’s superior, Colonel Sylvester Stadler, who commanded the Der Führer Regiment, had intervened by early evening to prevent further killings. After the executions of the men and the atrocities in the church, Diekmann drove to Limoges to deliver a report to regimental HQ.

Stadler was shocked and felt that this time he had gone too far. One report quotes him as saying “Diekmann, this may cost you dearly. I am going to ask the Division court at once for a court-martial investigation. I cannot allow the Regiment to be charged with something like this!”

An in-house investigation was held when they arrived in Normandy. As word spread among senior officers, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel himself offered to preside over the court-martial, having reputedly said to Hitler, “This kind of thing dishonors Germany.”

The Germans left Oradour sometime between 9 and 10:30 p.m., leaving behind a guard section. After the killing and looting, some had installed themselves in the Dupic family house on the north side of town to drink their way through M. Dupic’s fine wines and champagne. It was the last to be set on fire. They had also set up a giant spotlight for surveillance although the light generated by the burning town was enough to expose any survivors who were still capable of escaping.

One witness who saw the troops leave later stated, “Among the military trucks was the car belonging to M. Dupic, the merchant and cloth dealer. There was also the wine merchant’s van. On one of the trucks, a German was playing the accordion.” The trucks were heavily loaded with bags, bundles, and bottles from the looting.

Some locals did manage to get inside the town the next day and what they found was to haunt them forever. Those first on the scene were already aware of the atrocities inflicted on innocent women and children in their place of worship, but the church had a further shock in store for them. On top of one pile of charred remains was the naked body of a young woman who showed all the signs of having been violated before being murdered and thrown among the other victims of this unspeakable crime.

It was also clear that whatever the women were going through, they were putting their children first. Behind the altar were a large number of children’s bodies. When the blast blew out the windows, through one of which Marguerite had escaped, it allowed some oxygen to get in and the mothers had selflessly given their children the best chance of survival while they suffered the smoke.

Beyond the church and the six places of execution were other bodies, a couple in a wheelbarrow, several in wells, and what appeared to be human remains in a brazier at the bakery. Throughout the town were the poignant and pathetic signs of everyday lives that had suddenly been cut short, like the suitcases and children’s toys scattered at a plane-crash site. The clocks really had stopped in Oradour.

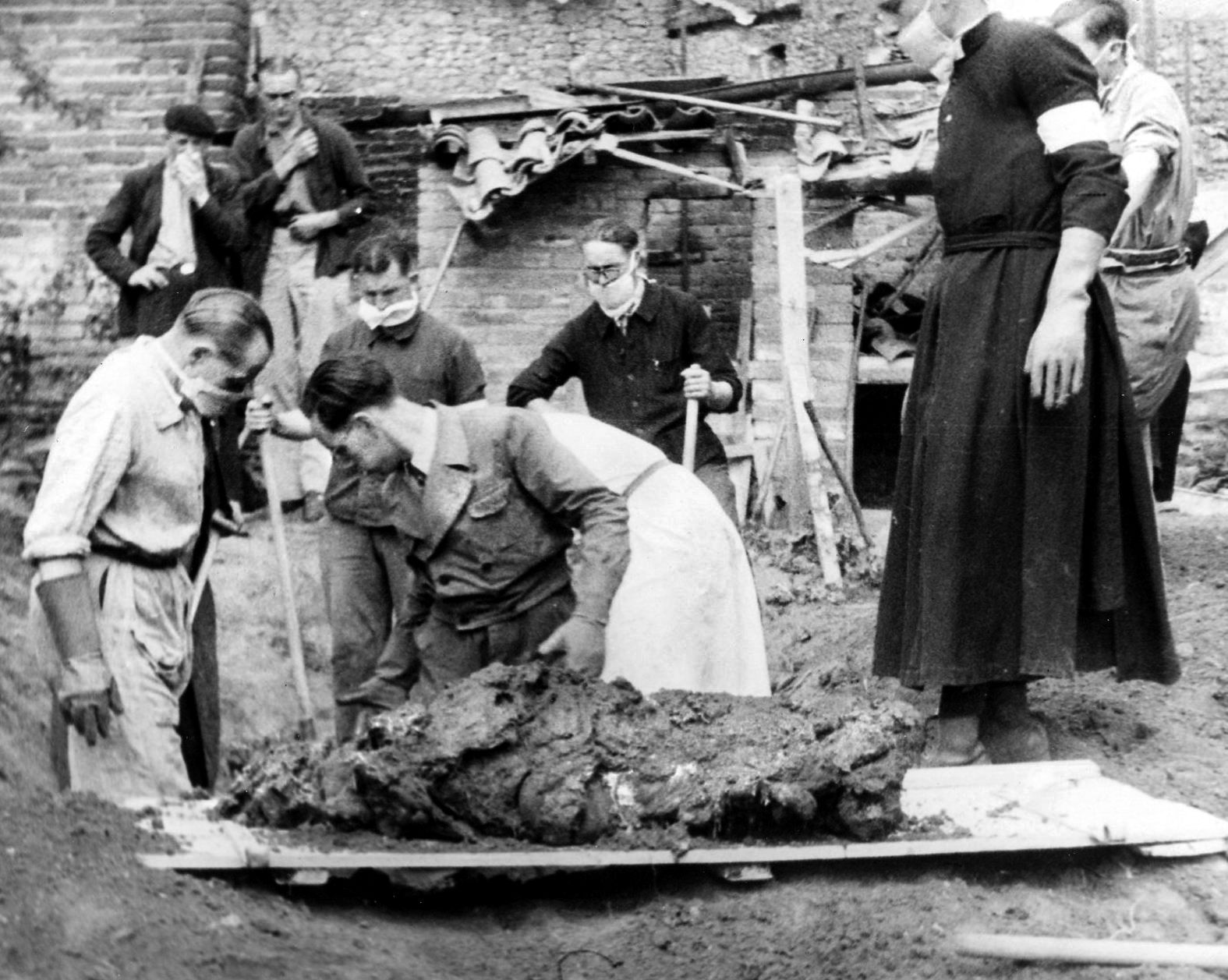

A German burial detail actually returned on Sunday to take care of the bodies and posted guards who fired at anyone who approached from the woods. As was their practice on the Eastern Front, they also tried to make identification of the remains impossible. The plan had been to dig two mass graves, one near the church and the other near the Denis wine store, one of the execution spots, but it soon became obvious that the size of the task was overwhelming.

Word of the massacre had spread far and wide and there was little point in trying to cover up the evidence, so late on the Tuesday after the massacre, the soldiers left and continued northwards in accordance with their previous orders.

French aid workers, together with some of the locals, then moved in to recover and identify the victims, exhuming the hasty German burials and collecting any other bodies they could find, together with their personal effects.

The hot summer sun made the gruesome task unbearable, but it was the least that they could do for the ones who had suffered so much and for their families who waited anxiously for any news that would bring them some sort of closure. It was eventually agreed that the dead numbered 642 but only 52 of these could be positively identified. The remainder had to be officially classified as “missing,” because there was nothing left to identify.

Immediately after the massacre, the survivors found temporary accommodation and did their best to get on with their lives. None of them would have heard of, or have known how to deal with, post-traumatic stress disorders, yet they had experienced horrors that a seasoned soldier would have had difficulty coping with.

As the war drew to a close, the survivors cherished the hope that they would see justice for these crimes, and this helped to keep them going. Oradour could not be resurrected, but its people felt it should be kept as a memorial, a view shared by General Charles de Gaulle when he visited the ruins on March 4, 1945. A new town was built nearby which became home to survivors and a new generation of Oradouranes.

The Pursuit of Truth and Justice

It was not until 1953, in the city of Bordeaux that a war-crimes tribunal sat in judgment over Oradour. As simple country folk, they found this time scale mystifying and unacceptable, but they were at the mercy of international law and post-war politics. To begin with, the French war-crimes law could not apply to French citizens and some of those involved in the massacre were from Alsace, which had still been part of France. This law was not changed till 1948.

Then there were issues of collective responsibility—what blame could be attributed to low-ranking soldiers acting under orders and who faced death themselves if they disobeyed? Furthermore, the Germans had been guilty of war crimes themselves by pressing young Frenchmen from Alsace into service with the SS.

It became clear that even when the law was sufficiently clear on procedures, it would be difficult to pursue justice in a way that was acceptable to all. The situation was clear to many people from Oradour who wanted punishment for those involved in the massacre. But Alsace also wanted justice for its young men who had been forcibly and illegally conscripted into the SS, which forced them to commit acts of barbarism against their own people.

Lorraine, normally supportive of Alsace because both areas had been overrun by Germany, saw the situation differently. Forty-four of those murdered on June 10, including a school full of children, had been refugees from the Moselle département of Lorraine, from the towns of Charly and Montoy-Flanville, and if some of their killers had been from Alsace, why should they be treated any differently than the Germans?

When the trial started, there was a major confrontation over whether the Alsatian soldiers should be tried separately from the Germans. This and other issues sparked demonstrations and widespread media activity, which would put further pressure on the pursuit of truth and justice within the courtroom. It was looking like a “no-win” situation from the start.

(The story of the trial is meticulously described in Oradour: the Final Verdict, a 2007 book by retired American lawyer and local French resident Douglas W. Hayes after sifting through all the relevant documentation, and presents a most-detailed analysis and conclusion of what took place in the Bordeaux courtroom).

Identifying those responsible for the massacre was to present challenges. For many of the 200 men from the 3rd Company of the 1st battalion, Der Führer Regiment, present on that day, karma had already intervened, spectacularly so in the case of Kommandant Adolf Diekmann, who was decapitated by a shell from a Sherman tank soon after the regiment arrived in Normandy.

The whole division had suffered huge losses in engaging the D-Day invaders, the failed counter-attack at Mortain and in the Falaise-Chambois pocket where they were surrounded and mown down as they tried to exit the Normandy battlefields.

Of the 28 Alsatians known to be present at the massacre, 15 had been killed in action by the end of the war. The remaining 13 were identified to be sent to Bordeaux for trial. Some of them had risked their lives and those of their families back home after the Oradour massacre by deserting and even joining the French Résistance, and two had been held in custody since the end of the war. They did their best to distance themselves from the SS and demonstrate, very bravely in many cases, that their allegiances lay with France, but they could not deny where they were on June 10, 1944.

Finding the Germans present on the day was more difficult, and 44 of them, including Captain Kahn and Lieutenant Barth would eventually be tried in absentia, because they could not be traced or because of extradition difficulties. Seven had been held in POW camps where they were kept pending trial. But the long wait created opportunities to fabricate alibis and shift the blame, when questioned, to the men who had already been killed and others outside the courtroom. The indictment that was finally read out in court did not name either the division commander, General Lammerding, or the regimental commander, Colonel Stadler.

The trial provided confirmation of much that was already known, and revealed more detail concerning individual responsibilities on the day. The only German officer present, the adjutant Karl Lens, had occupied a more administrative role and did not appear to be directly involved in the massacre.

In contrast, much detail was provided by George Boos, the only Alsatian to actually admit to having volunteered for the SS and who, significantly, was seated with the German defendants during the trial. Whereas the other Alsatians (who identified themselves as malgré nous, fighting in a German uniform despite being French) pleaded that they had been forcibly conscripted, Boos presented himself as a German soldier.

He confirmed most of the details presented by other defendants but denied his involvement in the executions at the Desourteaux garage, which stood opposite the bakery. It was felt that he was trying to distance himself from one of the most hideous allegations—that a child was burnt alive in the brazier of the bakery.

In different ways, the defendants in the courtroom tried to play down their roles in the massacre, especially the Alsatians, but several of the latter had to admit they had been members of firing squads or helped to generate the fires which had burned some of the victims alive. Most shielded behind the fact that they were under orders. One of them who had admitted, when he returned home after the war, to shooting a woman outside of the town was tried and technically sentenced to death but remained in prison until the trial.

One of the most harrowing stages of the trial was the testimony of the witnesses who had lived through the ordeal. All five of the band of brothers from the Laudy barn were present, as were those who had hidden in lofts and corners of buildings where they could hear or see what was happening.

Little Roger Godfrin, now a strapping 16-year-old, manfully won the attention of the courtroom, but it was Marguerite Rouffanche, the sole survivor of the church, who generated the most emotion. Hospitalized for almost a year and mentally scarred for life, she detailed the agony of her story. Despite her traumas, she battled through to the age of 91, but the lone name on her tomb in Oradour cemetery suggests that the remains of her husband, her daughters and her grandson were not sufficiently identifiable to share the family grave.

After 32 hours of distressing questioning and testimony in the courtroom, a verdict was announced at 2:30 a.m. on Friday the 13th. The hour chosen was an attempt to reduce possible demonstrations outside the courtroom as emotions were running high while the trial continued.

The verdicts were: death to all the Germans tried in absentia and to the German adjutant Lenz, as the only officer to be rounded up, and to George Boos, the Alsatian who had volunteered for the SS. For the rest of the defendants, the sentences comprised several years of hard labor. The verdicts were unanimous except in the case of the Alsatian malgré nous. One more judge voting in their favor would have resulted in their acquittal.

The results were not received favorably in the Limousin region, or in Alsace, but for different reasons. There was a resurgence of the animosities present at the start of the trial and a bill was presented to the legislature for an amnesty that would acknowledge that the Alsatians were innocent by virtue of their enforced conscription.

This was eventually voted through, resulting in violent demonstrations in Limousin, including the return of the Légion d’Honneur presented to the people of Oradour by the President of France, and war memorials were covered in black cloth. The survivors and victims of Oradour felt betrayed.

No death penalties were ever applied to the defendants. The sentences imposed on Karl Lenz and Georges Boos were commuted and within six years they were free men. The divisional and regimental commanders, General Lammerding and Colonel Stadler, who claimed that the massacre was Diekmann’s decision were never extradited.

The company commander, Captain Otto Kahn, despite being condemned to death for another war crime, was also never extradited and lived until 1977. His deputy, 2nd Lt. Heinz Barth was eventually arrested in 1981, and his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He was released in 1997 on age and health grounds, but survived another 10 years, when he died at the age of 86.

Oradour Today

Today, as in 1944, Oradour is well off the beaten track for tourists. For a determined visitor, an internal flight to Limoges and a 12-mile drive by taxi or rental car from the airport will provide the easiest method of access. The site is managed by the Centre de la Mémoire, which acts as a museum and information center. Visitors walk through the center and emerge from a tunnel facing the gates of the ruined town.

Everything has been kept as it was on June 10, 1944 except for the inconspicuous building supports placed in strategic places for safety reasons. The places of execution and other points of significance are respectfully signposted. Rusting cars and blackened walls add to the drama of the place. Visitors who may have walked through the town of Pompeii, now excavated after being overwhelmed by the volcano Vesuvius in Roman times, cannot fail to make a comparison with another community where life was cut short.

It was definitely the correct decision to leave the town where it fell and turn it into an open-air museum to remind us of what the human race is capable of doing to itself in wartime. Hundreds of thousands of visitors pass through its gates every year, despite its out-of-the-way location and then discover the new community that has risen phoenix-like beside the ruins.

It takes more than guns and bombs to kill a town like Oradour.

The author, who lives in Normandy, is a frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments