By Donald J. Roberts II

As the nine C-47s flew closer to the drop zone, the lead plane descended to an altitude of four hundred feet. Lieutenant John Ringler, the jumpmaster in the lead plane, stood in the doorway and saw the open field that was to be used as the drop-zone approach. Behind Ringler’s plane flew the remainder of his B Company, 1/511th, 11th Airborne Division paratroopers. The now-famous Los Banos Raid was about to commence in full.

From his position in the open doorway, Ringler saw white smoke from a smoke grenade thrown by 11th Airborne reconnaissance personnel on the drop zone. Ringler immediately turned to his stick of paratroopers behind him and yelled, “Close in the door.” Within seconds, at exactly 7 am, the lead C-47 flew directly over the drop zone and Ringler shouted, “Let’s go,” and jumped out the door. Their attempt to liberate 2,000 prisoners of war was under way.

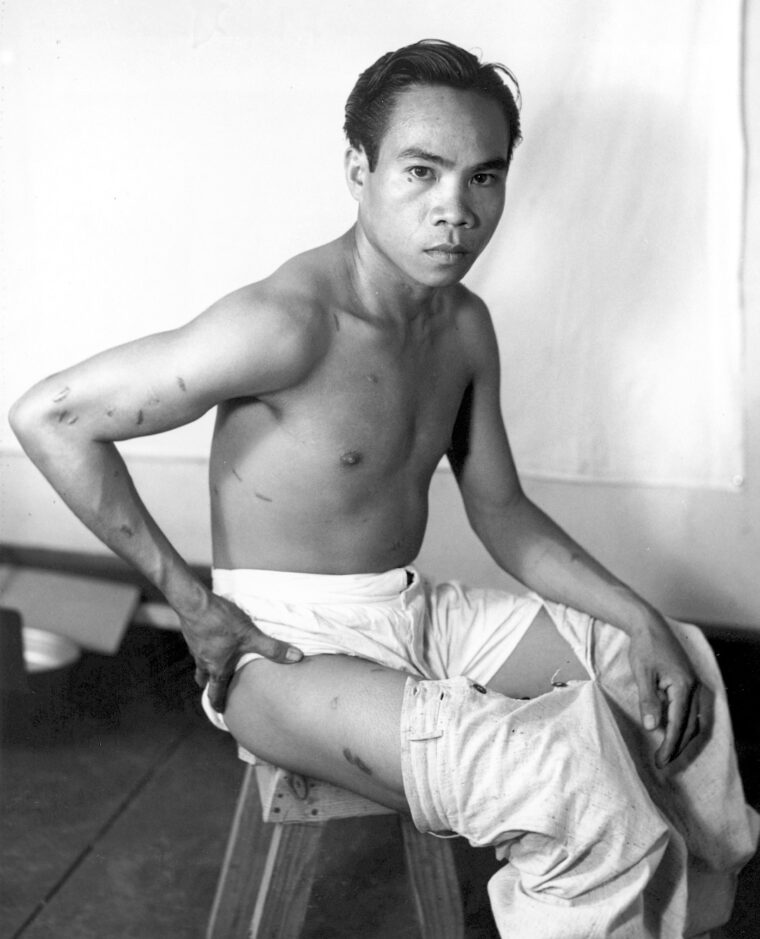

Following the Japanese sweep across the Philippines in late 1941 and early 1942, thousands of U.S. and Filipino military and civilian personnel were either shipped to prison camps off the islands or were forced to face imprisonment in one of the many POW camps on the islands.

It was not until January 1945, following a long and exhaustive island-hopping campaign through the South Pacific, that General Douglas MacArthur—personally ordered to escape the Japanese onslaught—was ready to fulfill his promise to return to and retake the Philippines.

Because much of MacArthur’s long career had been spent in the Philippines, he knew and had served with countless numbers of civilians and servicemen who were now being held in Japanese internment camps. Following the Allied invasion, MacArthur learned that Japanese guards had begun to increase the level of abuse of prisoners throughout the islands. MacArthur knew that the longer it took to rescue the inmates, the more horror they would be forced to endure. Regardless of the tough fighting his troops were experiencing, MacArthur ordered “special operations” to be planned and conducted by the Army in order to rescue prisoners.

” These Half-Starved and Ill-Treated People Would Die Unless We Rescued Them.”

In his Reminiscences MacArthur says: “There was no fixed timetable [to reconquer Luzon]. I hoped to proceed as rapidly as possible, especially as time was an element connected with the release of our prisoners.… I knew that many of these half-starved and ill-treated people would die unless we rescued them promptly.”

During the weeks of late January and early February of 1945, rescue missions were conducted in many locations. One, which was launched in late January, included members of the 6th Ranger Battalion. These men freed some 500 prisoners at Pangatian. Another rescue operation, led by the 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, assaulted Santo Tomas University in Manila. There the soldiers were able to liberate more than 3,700 prisoners. Later, on February 4, the 8th Cavalry was able to free another 500 internees and nearly 800 Allied POWs from the Old Bilibid Prison in Manila. The final rescue operation planned during this time was to free the inmates at Los Baños Internment Camp. The assignment was handed to the 11th Airborne Division.

Los Baños prison was located on the campus of the College of Agriculture of the University of the Philippines. The college was located 25 miles south of Manila, deep behind enemy lines, and along the southern shoreline of a huge inland lake, Laguna de Bay. Orders for the liberation were sent to Maj. Gen. Joseph Swing, commanding the 11th Airborne Division, on February 4, 1945. Because his men were fighting their way northward toward Manila and were involved in some very heavy combat, Swing immediately contacted Lt. Gen. Oscar Griswold, who commanded the XIV Corps, which was conducting the major offensive against Japanese positions in and around Manila.

Swing asked Griswold if the rescue mission could be postponed until the 11th Airborne Division accomplished its mission to help capture Manila. Griswold realized how difficult the fighting had become and granted Swing’s request. However, he instructed Swing to “liberate the prisoners at Los Baños as soon as it becomes possible for you to disengage a force of sufficient size to carry out that mission.”

Although Swing was granted a postponement on the liberation mission, he instructed his G-2 (Intelligence), Lt. Col. Henry J. Muller, to gather information about the camp. At the same time, Swing ordered his G-3 (Operations), Colonel Douglas P. Quandt, to begin planning how to reach the camp, defeat the enemy guarding it, and evacuate all prisoners safely.

The Prison Compound Was Surrounded by Two 6ft. Tall Barb Wire Fences

In order to obtain accurate information on the Los Baños camp, Muller used a variety of resources to discover locations, defenses, and weaknesses. He used information from the division reconnaissance platoon, aerial photographs, guerrilla units, and Filipino civilians.

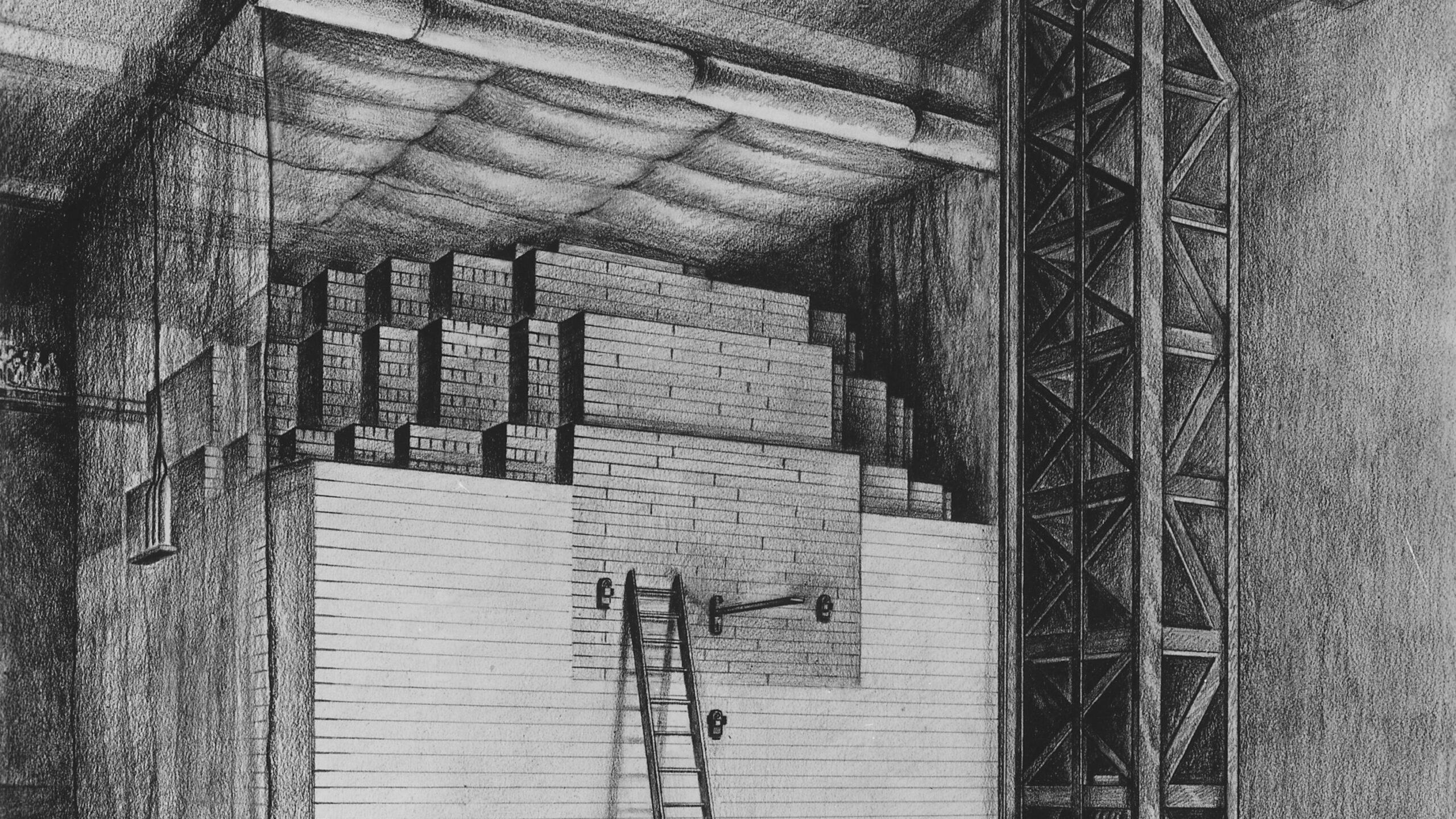

Muller learned that the prison compound had two barbed-wire perimeter fences around it, each six feet tall. Spaced along the fence line were pillboxes and several guard towers. Each position was manned by at least two guards armed with rifles and machine guns. Filipino guerrillas reported that prisoners left the camp every morning on work details that included finding firewood or obtaining food in the town.

As Lt. Col. Muller gathered his intelligence, he was helped by Major Jay D. Vanderpool, who had sneaked into Luzon in the fall of 1944 from a submarine. Since that time he had organized, helped train, and helped to plan many guerrilla operations and attacks against the Japanese around Cavite, Batangas, and areas west of Laguna de Bay. In fact, Vanderpool had planned an attack on Los Baños in which only Filipino guerrillas would have been used. In the end, Vanderpool had decided that to ensure the safety of all the prisoners in the camp, such a mission would require a larger force.

Much of what Vanderpool had learned, however, went into the planning of the operation. Then, just prior to the final planning stage, Muller and Vanderpool received very useful information from a Los Baños escaped prisoner, Peter Miles. Miles was one of many prisoners who would venture out from the compound through weak spots in the camp’s containment measures to search for food to buy. The prisoners would then return to Los Baños before first light and hopefully sneak back into the camp undetected. It was on one of the food- search escapades that Muller agreed to meet with Miles.

During the meeting, Miles was able to describe the interior of the prison. Muller learned the movements and routines of prisoners and guards. Miles described the general population of the prison as roughly 2,100, plus individuals who were either Protestant missionaries and their families; Catholic nuns and priests; or doctors, engineers, and other professional people, all with families. There were also a few hundred wives and children of U.S. servicemen imprisoned at Los Baños. Miles explained that there was one big question on the minds of all inmates: Would their guards or other Japanese soldiers in the area slaughter them rather than permit their liberation by the advancing Americans?

Following the meeting with Peter Miles, Muller, Quandt, Vanderpool, and the rest of the 11th Airborne Division planners began to finalize their plans. The mission would consist of four phases, a separate unit from the division conducting each phase.

Formulating the Los Baños Raid and Rescue Plan

The first phase of the operation would be carried out by the 11th Airborne’s Reconnaissance Platoon commanded by Lieutenant George Skau, along with nearly 80 Filipino guerrillas. Forty-eight hours before H-hour (the exact moment the mission would commence), the platoon would cross Laguna de Bay in small native boats called bancas and hide out in the vicinity of Los Baños until dark. Then these men would divide into three groups. The platoon and the Filipino guerrillas would secure a portion of beach east of the town, infiltrate as close as possible to the guard towers and defensive bunker emplacements, and secure a large field next to the compound to be used as a parachute drop zone.

Phase two would be a parachute drop of Lieutenant John Ringler’s B Company, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry. Once Ringler’s company was on the ground and assembled, the men would assault the prison compound with elements of Skau’s recon platoon. The attack was meant to kill or capture the guards and then prepare and assemble the inmates for extraction to safety.

The third part of the plan involved a formation of 59 amphibious “amtracs,” each large enough to carry a platoon of fully equipped soldiers. They would leave from Mamatid on the west shore of Laguna de Bay. They were to set out in the early hours of “D-day” and time their arrival on the shore at Los Baños at exactly H-hour. At that time, C Company, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry would deploy from the amtracs and set up roadblocks to prevent elements of the Japanese 8th Division from launching a counterattack. A company of artillerymen from Battery D, 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion would deploy from the amtracs as well. Their mission was to establish and secure the beachhead east of Los Baños. And A Company, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry, would secure the area around the perimeter of the prison.

The fourth phase of the operation included the 1st Battalion, 188th Glider Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Ernest La Flamme. While the 1/511th attacked the prison compound, the 1/188th was assigned the task of conducting a diversionary attack to the west. La Flamme was ordered to advance his glidermen across the San Juan River from Mamatid and move toward Los Baños. The glider battalion had two objectives: engage as many enemy troops as possible and, eventually, link up with the paratroopers at the prison camp in the event they had to fight their way out of Los Baños.

As the plan developed, Quandt outlined the mission to Major Henry Burgess, who was commander of the 1st/511th Parachute Infantry, which was assigned the mission to liberate the camp. As Burgess began to concentrate on the final preparations for the mission, he realized the “tremendous obstacles” to be faced by his battalion and he worried, “How could my force of 412 paratroopers slip undetected deep into Japanese-controlled territory, wipe out a large number of enemy guards at the camp before they could kill the inmates, and bring back to safety, 2,200 weak men, women, and children, many of whom were unable to walk?”

Parachute Assault on the Los Baños Prison Camp

On February 20, General Swing believed that he finally had accomplished enough of his objectives in Manila to allow the rescue mission to proceed. On the same day, the commander of B Company, 1st/511th, Lieutenant John M. Ringler, was ordered to report to division headquarters at Paranaque. Once there, he was briefed on the Los Baños mission and told that it would be his company making the parachute assault on the prison camp.

Division planners explained to Ringler that parachutes would be flown in from Leyte the next day. During the jump briefing, Ringler learned that Nichols Field, which had just recently been captured near Manila, would be cleared, and planes would be readied for the mission. Ringler was advised that just before B Company’s drop, the drop zone would be marked by guerrillas using white smoke markers. The jump altitude would be 400 feet so the men would not be exposed to enemy ground fire for any longer than was necessary.

That night, Lieutenants Skau and Haggerty, (who was an engineer from the 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion) left Paranaque to scout the Los Baños area. The two officers crossed Laguna de Bay by bancas on their way to Nanhaya, a small village near the prison camp. Once there, they met with two escaped inmates, Ben Edwards and Freddy Zervoulakos. Both men agreed to escort Skau and Haggerty. Along with a few guerrillas from Hunter’s 45th Regiment, the party moved quickly but quietly toward Los Baños.

The first thing the young officers made sure of was that the beach east of Los Baños was firm enough to support the column of amtracs as they rumbled onshore. They both decided it was. Next, the party checked the wooden bridges to ensure they were strong enough to support fully loaded amtracs. Again, both officers agreed that the bridges were safe. The third area Skau and Haggerty wanted to inspect was the drop zone that Doug Quandt had picked from the maps of the Los Baños area. After a careful analysis, Skau decided that the drop zone was sufficient, even though there were powerlines and railroad tracks bordering the field. The final location to be checked was the camp itself.

The reconnaissance group stealthily moved from the drop zone along the route Ringler’s men would take to the camp following their jump. They located the many guard towers spaced around the perimeter and decided that Ringler’s men would be able to penetrate the camp’s defenses. As soon as the men were satisfied they had learned all they could, the group moved back to the beach. Within minutes, Skau and Haggerty were back in their bancas and returning to Paranaque.

The next day, February 21, the troops that were to participate in the rescue mission were pulled out of the line in Manila. Division planners then decided that “D-day” for the mission would be February 23, just two days away.

During the day of the 21st, Skau got a few hours sleep. After dark, he moved his reconnaissance platoon to Mamatid and met with the guerrillas, who came with bancas. They began shoving off at 7 pm. Most of the force landed near Los Baños in the early morning and moved into the jungle to hide. The remainder of Skau’s force came ashore after daylight and it, too, disappeared into the jungle for the wait until the following night.

The next day the other rescue units moved to their staging areas. A and C Companies along with Battery D marched from Manila to the town of Mamatid. Once there, they prepared their equipment and weapons for loading onto the amtracs. At 4 am on the 23rd, just three hours before H-hour, the paratroopers were to load onto the amtracs for their trip across Laguna de Bay to Los Baños.

“We Could Feel Something in the Air.”

Moving on the 22nd as well was La Flamme’s Glider Infantry. This force, designated to conduct the diversionary attack, moved to an area near Mamatid and prepared for its attack. They planned to maneuver down the road from Mamatid to an area near the San Juan River and hopefully draw many enemy troops away from the Los Baños area.

Ringler’s B Company was pulled out of the line and trucked to the newly liberated New Bilibid Prison. The paratroopers were instructed to offload from the trucks, and all members of B Company were assigned cells to sleep in during the night. One member of B Company recalled: “We could feel something in the air. And the rumors! Something big, something important was coming up. What was it all about? And some thanks for all the fighting we had been doing! We were being put in a prison.”

On the afternoon of the 22nd, Ringler joined his men at New Bilibid Prison. He called his men together and explained what the secret mission was. Ringler warned, “Watch out in particular for the high-tension line bordering the drop zone.… If you hit it, you’re fried!”

Loading back onto trucks, the paratroopers were moved to Nichols Field, where they spent a restless night under the wings of the planes.

At 3 am on the 23rd, just four hours before the attack was to begin, Skau began to move his men from their hiding places in the jungle to their final positions for attack. He sent one squad to the beach just east of Los Baños with instructions to mark the beach approach with smoke grenades for the amtracs at exactly 6:58. Another squad was sent to the selected drop zone. At exactly 6:58 this squad was supposed to mark the drop zone with smoke grenades for the approaching flight of C-47s carrying John Ringler’s paratroopers. The remainder of Skau’s platoon and guerrillas crawled through the jungle to within range of the guard towers and pillboxes of the prison compound. Once in place, the men prepared their weapons and waited for H-hour, just a few hours away.

As Skau’s men moved into position, Burgess’s men began strapping their gear on, checking weapons, and moving out to their assigned amtracs. By 5:15, all amtracs were in the water and under way. Using handheld compasses to guide them, the force, in a column of threes, headed toward Los Baños.

A Shocking Development for the Division Planners

By 5:30, the men of B Company were struggling into their parachute harnesses and strapping on their equipment. At 6 o’clock, nine C-47s started their engines and within 30 minutes were airborne. The aircraft fell into three formations of three planes, each formation in the shape of a V. For 40 minutes the planes circled Nichols Field and then turned south. The jumpmasters in each aircraft stood in the open doorways, and as the planes flew across Laguna de Bay, they were able to look down and see the amtracs churning away across the lake.

an amtrack, one of the

amphibious vehicles used

in the Los Baños raid.

As the men of the 11th Airborne Division approached their objective from different directions, none of them realized the drama that had unfolded during the night. A P-61 Black Widow night reconnaissance plane had returned from its mission to report a great number of trucks, all with headlights on, moving in the direction of the Los Baños camp. Division planners were shocked. What did this mean? Did the Japanese learn about the rescue and then decide to relocate all the prisoners before the attack? Or were they sending in hundreds of reinforcements in order to defend the camp? General Swing was notified immediately. He thought for only a few minutes. He knew that he could recall everybody except Skau’s men, who would begin the attack at exactly 6:58—nothing could stop that. So he allowed the mission to proceed.

At 6:45, the Los Baños camp began to stir. Hundreds of prisoners began filing out of their barracks and lined up for a head count. At the same time, most of the guards began their daily routine of exercise. Witnessing all this were Skau’s concealed men.

Inside the C-47s, Ringler’s men were checking their equipment and parachute harnesses one last time as they stood waiting to jump. Ringler, the jumpmaster in the lead aircraft, leaned out the aircraft door and checked to see if all airplanes were properly aligned for the drop. At precisely 6:58, Skau’s men at the drop zone popped white smoke grenades and threw them onto the field. Ringler now looked for the drop zone. He saw white smoke billowing up from the ground—the mission was on.

Inside the prison camp the inmates heard and then saw the low-flying aircraft approach. All of a sudden, parachutes began filling the sky. James Bateman, a 20-year-old prisoner, remembered: “We all thought this would be the last day of our lives, that we would all be executed.” [Japanese guards had ordered many of the prisoners to begin digging long trenches just outside the camp. Many inmates speculated that the trenches would be used for mass burial sites.] “The parachutes rained out of the sky. At first we thought they were dropping food in the camp. Then we realized they were American soldiers. We yelled and screamed and danced with joy.”

Skau’s Men Ran Into the Camp, Killing Any Japanese Guards They Encountered.

Just outside the camp, Skau’s men remained hidden until they saw the first parachute. Then they opened up on the guards along the perimeter. For about 15 minutes, the reconnaissance force assaulted pillboxes, bunkers, and guard towers. Knocking out the main gate, Skau’s men ran into the camp, killing any Japanese guards they encountered.

By 7:15, Ringler had his men assembled and moving toward the camp. Within minutes they had killed many of the guards who had tried to run away. As Ringler’s men entered the compound, they joined with Skau’s group and began to hunt down the remaining guards.

On Laguna de Bay, Burgess’s amphibious column rumbled ashore at exactly 7 am, right on schedule. Burgess dispatched C Company westward to establish a roadblock near the town of Los Baños. A Company was sent to the east to set up another blocking position. Then Captain Lou Burris’s D Battery, 457th Field Artillery was offloaded. Burris had been briefed only the day before by General Farrell, the division artillery commander. Farrell told Burris: “This operation has been kept secret because there are 10,000 Japanese troops within a two-and-a-half-hour truck ride of the camp. Your job is to block them with your battery. There is only one pass they can use through the hills. Be able to cover that pass with all four of your howitzers at all times.”

A short time after the guns were in place, they were firing on machine-gun positions east of Los Baños. With all of Burgess’s men in place, the amtracs proceeded full speed, about 15 miles an hour, toward the prison camp.

Back at the camp, the fighting petered out after about 20 minutes. The 243 guards had either been killed or had managed to run away. Not one of the 2,147 prisoners nor any member of the attacking force had been wounded or killed. The only casualty had been one of Ringler’s men, who had landed next to the railroad tracks during the jump and was knocked unconscious when his head struck the track.

Run Now, Pray Later!

Following the attack, prisoners began cheering wildly and greeted their liberators with hugs, kisses, and back-slapping as the soldiers began to bring some order in the camp. One prisoner shouted, “Thank God for the paratroopers.… These are the angels He sent to save us!” Another prisoner, a Catholic priest, began to pray, giving thanks for the liberators who had arrived out of nowhere. Shortly, a paratrooper who came running by stopped and touched the priest. He said, “Sorry, Father, no time for prayers now.… You gotta get packed so we can get you the hell outta here before more Japs arrive.”

As the soldiers tried to organize the huge mob of milling prisoners, Burgess’s amtracs approached the camp. The driver in the lead amtrac called to Burgess, “The gate’s closed, what should I do?” Burgess yelled back, “Crash through the damned thing!” The lead “trac” charged the gate and with a loud, crashing sound broke through. All the other vehicles followed.

The column made its way to the basefield and adjoining fields. There Burgess witnessed a scene of complete bedlam. By this time the entire camp was in a state of total celebration. The soldiers could not settle the “milling, laughing, and wandering” crowds of prisoners and get them organized for loading onto the amtracs.

At 7:45, John Ringler reported to Burgess. He said he and his men had not been able to organize any prisoners into groups to load onto the amtracs. There was too much confusion. He then told Burgess that some of the guards’ barracks were on fire and that it was causing many of the internees to move ahead of the fire toward the assembled amtracs.

As the minutes ticked by, Burgess finally received word from his blocking forces back near Laguna de Bay that there were indications that large enemy forces might be making preparations to attack the rescuers.

Realizing that the burning barracks might be his salvation, Burgess told Ringler to take some of his men to the upwind side of the camp and begin torching as many barracks as possible. Burgess thought that maybe the threat from fire would motivate the prisoners to gather their belongings and begin loading onto the amtracs. As soon as Ringler began burning the barracks, “the results were spectacular.” The paratroopers began to see the “internees pour out of their living quarters and into the loading area. Troops started clearing the barracks in advance of the fire and began carrying out to the loading area over 130 people who were too weak or too sick to walk.

Burgess was worried about the Tiger Division advancing on the camp. He had the most seriously weakened prisoners loaded first. It was soon apparent that the amtracs would have to make two trips in order to evacuate all prisoners and soldiers from the camp. The strongest inmates were kept back in case they had to fight their way out with the troopers if the Japanese attacked.

By 10 o’clock, the first load of evacuees was ready to move out. Burgess ordered the drivers to get them to Mamatid, discharge them, and return as soon as possible. An hour later, the camp was nearly deserted. The prisoners who had been left behind began walking toward the beachhead. A rear guard was formed from Ringler’s B Company and Skau’s Reconnaissance Platoon. There were very few guerrillas remaining in camp. When the attack had ended, most of the Filipinos had disappeared back into the jungle. It was assumed that they had returned to their units. Burgess recalled his security companies and instructed them to provide flank security for the march to the beach.

When Burgess, who was in the rear of the procession, reached the shore, he received alarming news. Lieutenant Tom Mesereau, C Company commander, reported to Burgess that he and his men had shot up a Japanese detachment. The bad news was that he believed a much larger force of enemy troops was approaching. “If the amtracs did not return soon, some 1,200 civilians and paratroopers might be trapped and wiped out.”

By this time in the mission, the diversionary attack of the 1/188th had advanced to just west of Los Baños. Here the battalion established a bridgehead next to the San Juan River and effectively blocked the road leading to Los Baños. Two of the glidermen in La Flamme’s battalion were killed in this attack.

“Very Quiet… No Complaints… No Levity… Just Quiet.”

During the next few anxious hours, as Burgess’s force secured the beachhead, Japanese mortar rounds were fired inside Burgess’s perimeter. At the same time, an occasional burst of machine-gun fire kept the paratroopers pinned to the ground. Finally, at around 1 o’clock in the afternoon, the amtracs appeared on the horizon and within minutes came motoring ashore onto the beachhead.

Burgess began to hurry the remaining civilians onto the vehicles as he gave the order to withdraw his men from the defensive perimeter. As the defensive line grew steadily smaller, Japanese fire “grew bolder and stronger.” By 3 o’clock, enemy fire on the beachhead increased to a dangerous level. As the last few amtracs loaded up and departed, the paratroopers sustained their first casualties. One trooper and one former prisoner each received minor injuries.

The Los Baños raid was one of the finest missions of its type in the war. Many of the methods utilized by Swing’s “Angels” during the planning and execution of the mission are still used in modern raiding techniques by today’s special operations forces. The courage and daring of the men of the 11th Airborne Division, without a doubt, spared the lives of over two thousand men, women, and children held prisoner by the Japanese.

Perhaps the most poignant memory of the mission was voiced by Dr. Boosalis, an 11th Airborne combat surgeon who participated in the rescue. Dr. Boosalis remembered the attitude and “fatigued features” of the troopers as they departed from Los Baños on the amtracs, each with orders to guard the freed civilians from any more horrors of war. As each vehicle passed, Boosalis saw in each paratrooper a “quietude.” Each man appeared to be wrapped in his own thoughts, thoughts about what had just occurred. The men were “very quiet.… no complaints.… no levity.… just quiet.”

My father’s family were liberated at Los Banos by these brave American soldiers and Filipino guerillas. My Aunt Patty Croft Kelly is still alive and well and lives in Oklahoma City. Her mother, Selma Croft smuggled an American flag into the camp and it was flown over the POW camp before liberation when the guards temporarily vacated the camp to prepare fortifications in Manila prior to being liberated. Angered by this the returning guards searched for the flag without success. My Aunt Patty recently donated this flag to the Special Forces Airborne Museum in Fayetteville N.C. Good article on a very dramatic rescue and an

interesting part of WW2 history.

The article doesnt recognize the true role of the Hunters ROTC Guerillas, who were the 1st to attack the Los Banos internment camp and force the Japanese guards out & who started releasing the internees minutes before the 1st paratrooper ever landed on camp grounds. There were 5 other Filipino guerilla groups also present with different respective roles that this article similarly failed to acknowledge.