One of the unlikeliest—and unluckiest—Confederate leaders was Pennsylvania-born general John C. Pemberton, who “married South,” as the saying went, only to go down in infamy as the man who surrendered Vicksburg to Ulysses S. Grant on the Fourth of July, 1863.

The 48-year-old Pemberton at first seemed well qualified to lead a Confederate army, having graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1837. He served in the Seminole War, the Mexican War, and the frontier clashes with Indians and Mormons in the decade leading up to the Civil War.

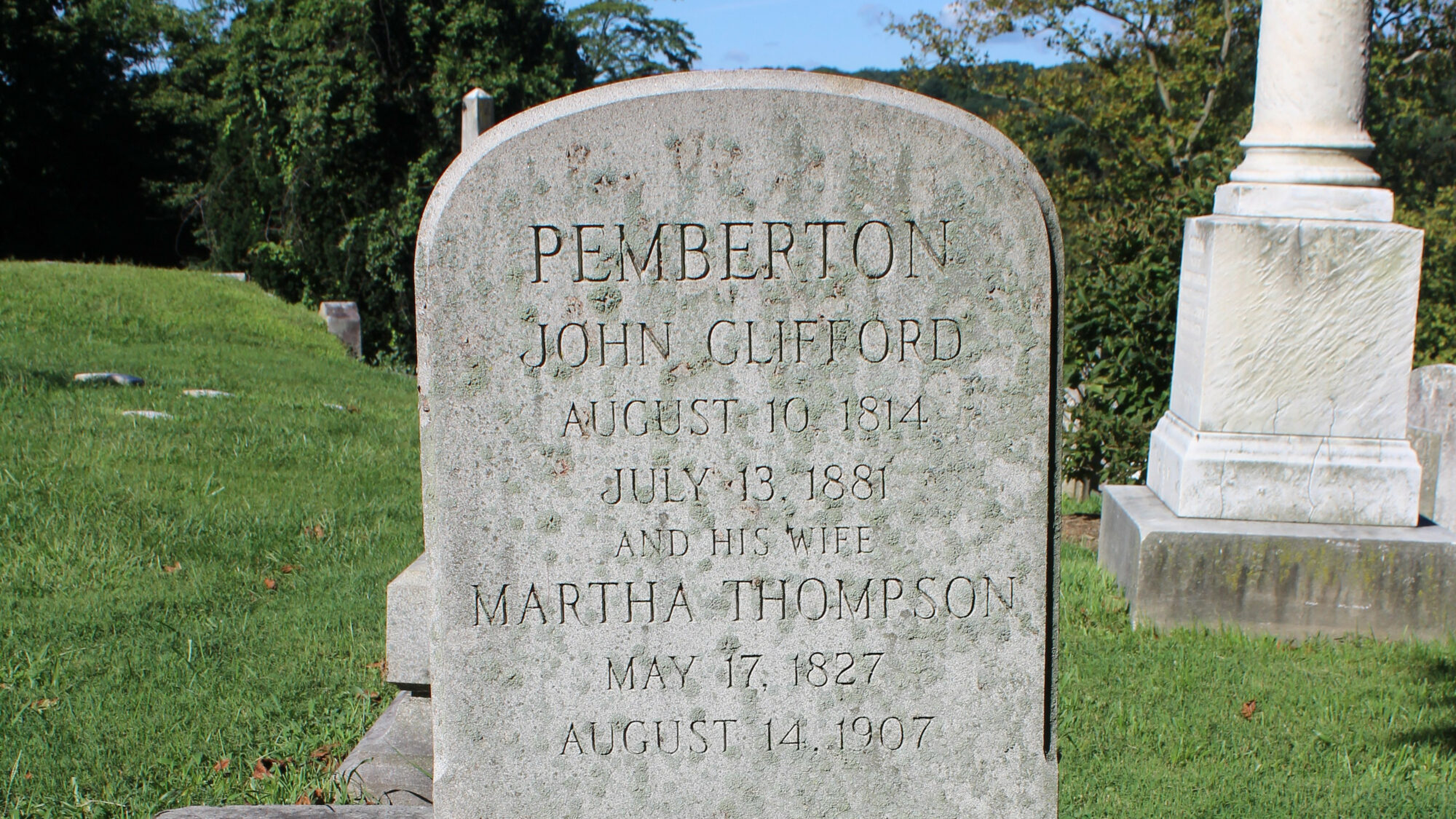

Although born into a wealthy Philadelphia family, Pemberton had adopted pro-southern attitudes at West Point and then sealed his allegiance by marrying Martha Thompson of Norfolk, Virginia. When the war broke out in 1861, he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army and accepted a colonel’s rank in the Confederacy.

Pemberton’s rise through the leadership ranks was as swift as it was inexplicable. Despite seeing virtually no battlefield action during the first two years of the war, he was steadily promoted from lieutenant colonel to major general. He seemed to have a knack for inheriting the commands of superior officers such as Robert E. Lee when they were called away to other duties.

Succeeding Lee as commander of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, Pemberton first evinced flaws in his leadership style. Against the outraged cries of native Charlestonians, he voluntarily abandoned the defense of Fort Sumter, declaring that the fort was militarily insignificant.

In response to the growing complaints, Confederate president Jefferson Davis transferred Pemberton to Mississippi in October 1862. Davis may have thought he was moving the controversial Pemberton to a more out-of-the-way location, but unfortunately the Mississippi front was about to heat up considerably.

Faced with the unenviable task of trying to prevent the tenacious Ulysses S. Grant from capturing Vicksburg and seizing control of the entire Mississippi Valley, Pemberton was hampered by conflicting orders from Davis and General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the newly created Department of the West. Davis ordered Pemberton to hold Vicksburg at all costs, while Johnston wanted the Pennsylvanian to make Grant’s army his main target. Predictably, the confusion quickly spelled disaster for Pemberton and the Confederates.

The ensuing defeat at Champion’s Hill, due in large part to Pemberton, ensured the capture of Vicksburg. Pemberton should have taken into account the Union commander’s dogmatic personality. Any hopes that Grant would give him favorable surrender terms were quickly dashed. Hoping to sweeten Grant’s mood, Pemberton made yet another public relations blunder, surrendering Vicksburg on July 4. Coupled with the Union victory at Gettysburg the previous day, the twin defeats foreshadowed the end, however delayed, for the Confederate cause.

It was not true, as one critic maintained, that Pemberton “had joined the South for the express purpose of betraying it.” That gave him both too little and too much credit. Pemberton could not have made a worse shambles of things if he had premeditated them. The truth was, he was simply overmatched against a superb general such as Grant. As one of his few remaining supporters conceded following the fall of Vicksburg, Pemberton was not a traitor; he was merely “a poor jerk,” in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments