Nearly 70 years after the conclusion of World War II, civilization has changed greatly. Communism in Eastern Europe has risen and fallen. Empires have crumbled. The specter of terrorism has emerged as the new enemy of global peace. In the meantime, the cities of Germany have been rebuilt, the German nation has served as a staunch ally of NATO, and the enmity of the Nazi era has been relegated to an ugly chapter of the past.

Reminders of that period of total war, however, sometimes rise up like visitors from another age, warning signs from a horrific past that will, hopefully, never be repeated.

Recently, a prolonged period of drought in Western Europe caused a number of rivers and lakes to reach their lowest water levels in decades. Even the mighty Rhine, the European father of waters, had ebbed substantially. So much so that at Koblenz, a city in west-central Germany at the confluence of the Rhine and Moselle Rivers whose name actually comes from the Latin word for “the meeting of the waters,” the bed of the great Rhine was exposed.

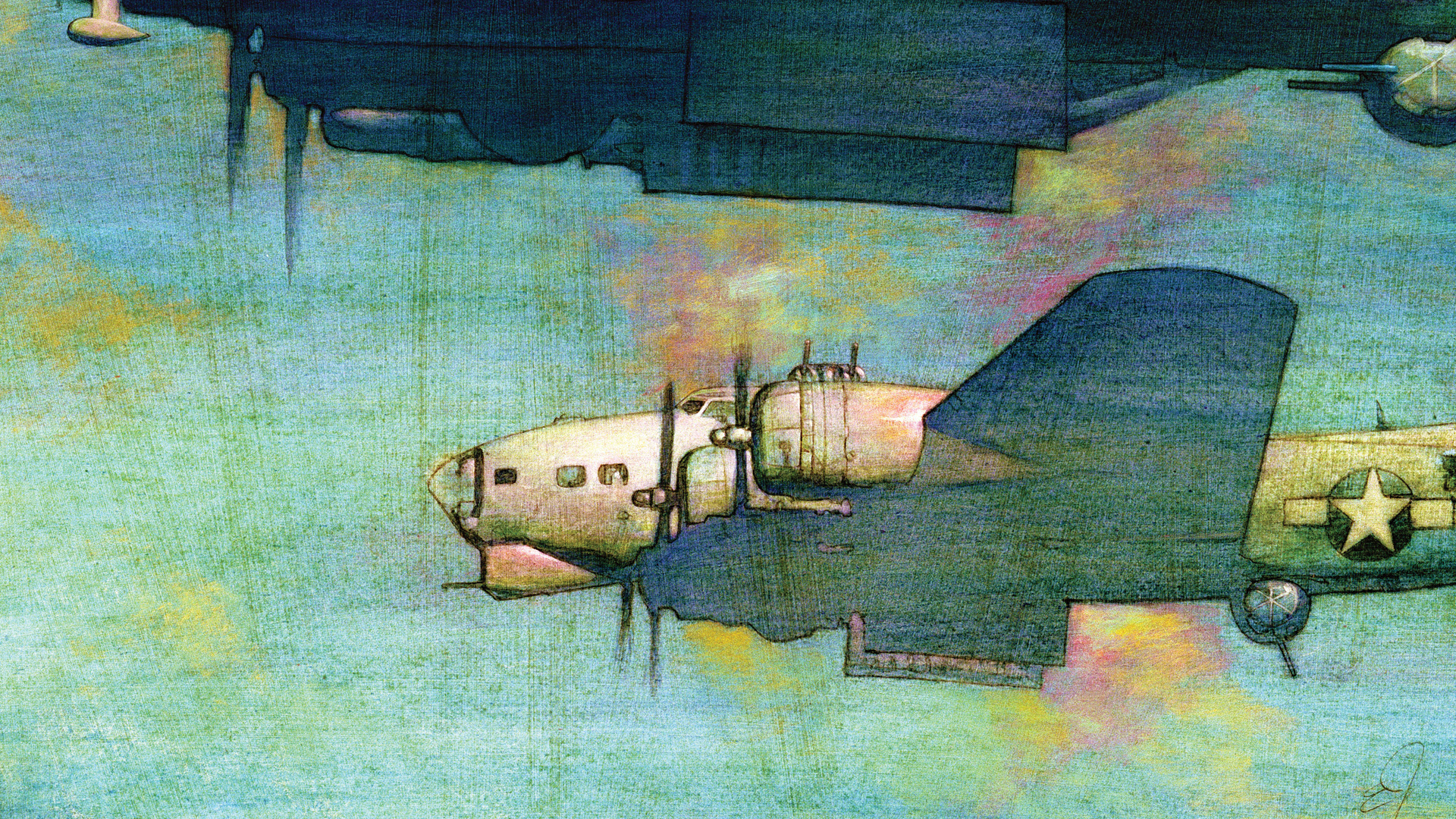

A large drum-like canister became visible, and shortly thereafter it was determined that the foreign object was an unexploded bomb dropped sometime between 1943 and 1945 by a bomber of the British Royal Air Force. No doubt, the discovery conjured up images of RAF Avro Lancasters flying in darkness high above the city, some bracketed by flak, chased by night fighters, and illuminated in the stabbing beams of searchlights, intent on delivering their cargoes of death.

Estimates are that as many as 250 bombs of the type discovered were dropped on Koblenz during the period. And these were no ordinary bombs. The high-explosive “Blockbuster” weighed an extraordinary 1,800 kilograms, or 4,000 pounds, and had been designed to destroy buildings and facilities in and near urban areas. Nearby, a second unexploded bomb, delivered by an aircraft of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, was found. Substantially smaller, this bomb weighed 125 kilograms, or 275 pounds, and was also capable of delivering a tremendous blast. A smoke grenade canister was also unearthed.

The discovery of unexploded ordnance in German cities during the postwar era is not unusual. Estimates indicate that approximately 600 tons of silent and potentially lethal bombs and artillery shells are discovered each year. Actually, in the summer of 2010, three people were killed in the city of Göttingen in Lower Saxony when a 500 kilogram (1,100 pound) bomb was accidentally detonated during the construction of a sports stadium. The significance of the Koblenz incident is simply that it is one of the largest such discoveries.

Authorities cordoned off an area of 1.25 miles and evacuated 45,000 people, slightly less than half the population of the city. Trains were stopped, traffic was halted, and 12,000 beds were made available at shelters. Hundreds of police officers stood by along with ambulances and rescue vehicles.

The smoke canister was detonated in a controlled explosion. Then, the high drama of the defusing process followed. Standing water was pumped from around the bombs, and a mountain of sandbags was stacked around the Blockbuster to absorb some of the blast should the unthinkable occur. One official speculated to a BBC reporter that if the Blockbuster had exploded it would have hurled shrapnel a distance of 1.5 kilometers, nearly a mile. Doors and windows would have been shattered or blown open by the shockwave and the high-pressure displacement of air.

One woman told the German newspaper Die Welt that her elderly relative had lived through the bombing of Koblenz during World War II and the flurry of activity related to this incident had brought frightening memories flooding back. For those of us who did not experience a World War II air raid, it is difficult to comprehend that the subject Blockbuster and the smaller bomb were merely two of many that rained down on German cities during World War II.

Bomb disposal experts successfully disarmed the relics during a nerve-wracking three-hour operation, and a local official related, “We are relieved.” It was a classic understatement.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments