By Eric Niderost

On the morning of February 16, 1940, two Royal Air Force Lockheed Hudson aircraft lifted off from Thornaby Airfield in northern England. Their mission was to locate the Altmark, an elusive German tanker that was last reported somewhere along the coast of Norway. Altmark’s foul holds were crammed with 300 British prisoners, seamen taken from a number of merchant ships sunk by the panzerschiffe (pocket battleship) Admiral Graf Spee. The German tanker was now making a desperate run for home—possibly to the port of Kiel or Hamburg.

The Hudsons had to find the Altmark. The alternative was too terrible to contemplate. The Germans would score a propaganda coup if one of their ships successfully escaped the British dragnet. But even more importantly, the seamen had to be rescued. If the Altmark reached port, the hapless prisoners would have to endure months, and probably years, of brutal German captivity.

Locating the Ship

Pilot officer C.W. McNeill was at the controls of “K for King,” or just “K” for short, keeping his eyes glued to the far horizon. Visibility was perfect; in fact, McNeill reckoned his men could see as many as 50 miles in all directions. The sea below them was a cobalt carpet, the dimpled blue waters accented by the sun’s sparkling rays. The overall effect was almost Mediterranean until the white clumps of pack ice in the distance brought an observer back to reality.

McNeill knew that the Altmark was either in the North Sea or in the Skagerrack, the strait that cuts between Norway and Denmark. The Hudsons encountered many ships, but none had the Altmark’s distinctive silhouette. Suddenly, a black shape appeared about 15 miles ahead. Could this be his elusive quarry? During his morning briefing McNeill had been told in no uncertain terms that the Altmark would be painted black with white deck tops. This mystery vessel was gray.

Banking his Hudson, McNeill circled the unknown ship, examining her stem to stern. Yes, it looked like the rough Altmark sketch that the pilots had been given, but he had to be sure. McNiell dived, flying so low he was almost skimming the water. Sure enough, Altmark was painted on the bow in bold letters. He had found the ship!

Time Running Out—Stay Now, or Return Later?

But now the pilot officer was faced with a crucial decision. It was around 1 o’clock in the afternoon, and the winter sun sets early in these northern climes. Altmark might escape under the cover of darkness. The officer piloting the other Hudson had also spotted the Altmark and was even now signaling their discovery back to their Thornaby home base. All signals had to be in code, and McNeill could imagine a crewman in the other plane painstakingly enciphering a message on a hand-held machine. Once received at base, it had to be deciphered then sent on to the Royal Navy.

No, time was running out. If Royal Navy warships had any chance of intercepting the Altmark, they had to know the German ship’s whereabouts immediately. McNeill wrote an “enemy first sighting” report, detailing that the Altmark was steaming south at 8 knots, 58 degrees, 17 minutes north, 06 degrees, 05 minutes east. The missive was handed over to the wireless operator with the instructions, “Bang it out, Skeekey.” In other words, transmit in plain language. This was against orders, but McNeill felt the circumstances warranted it.

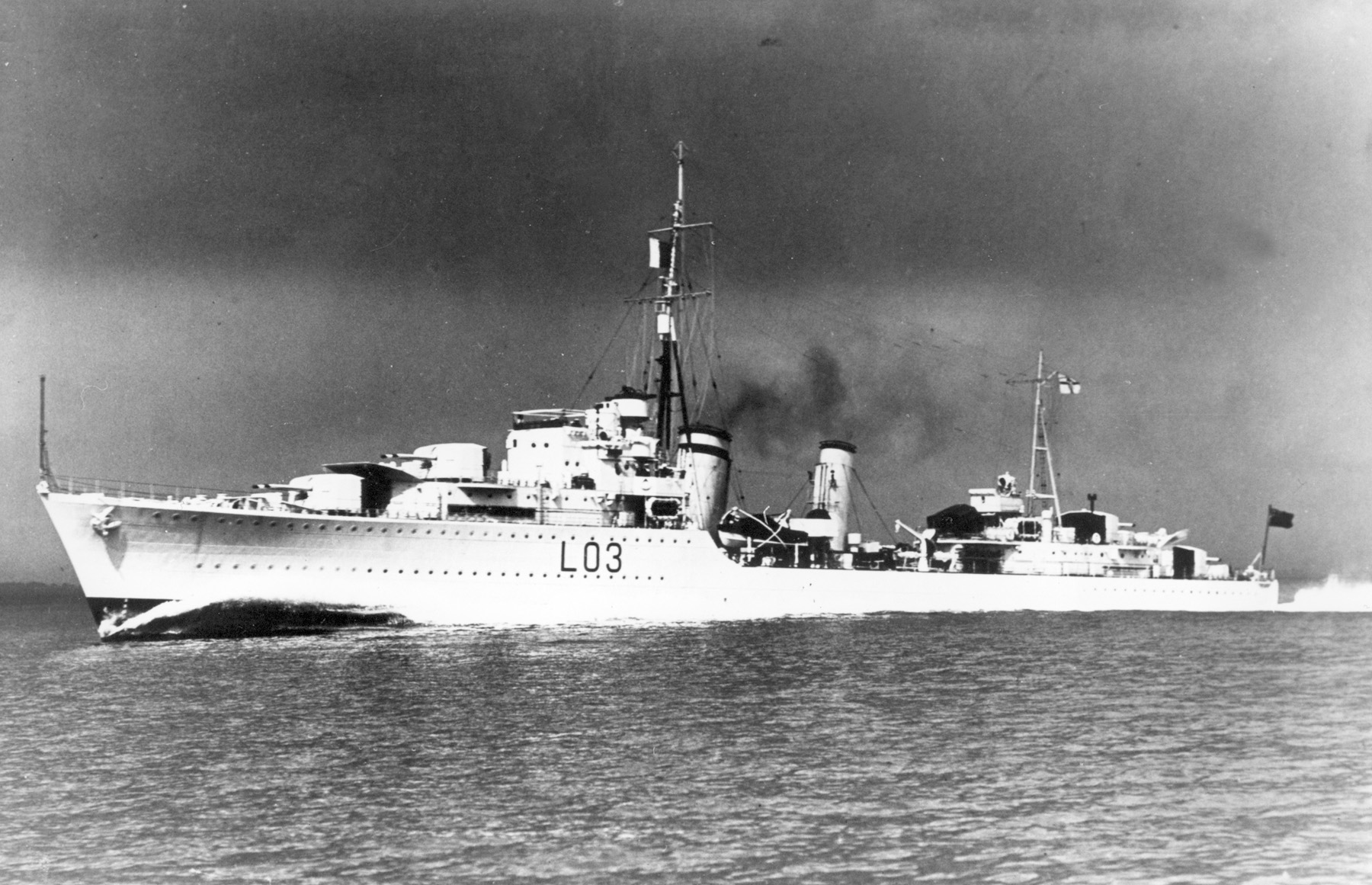

Their mission accomplished, the Hudsons headed back home. McNeill got a good dressing down by the Thornaby base commander. He had deliberately disobeyed orders by not sending the message in code. But luck was with him. The destroyer HMS Cossack had picked up his message and was even now taking steps to hunt the Altmark down. Cossack was the flagship of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla (DF), which included the cruiser Aethusa and the destroyers Sikh, Nubian, Ivanhoe, and Intrepid.

Captain Philip Vian was commander of 4th DF, and it was he who had chosen the Cossack to be his flagship. Vian was known as a superb officer, quick-witted and aggressive, and when McNeill’s message was received he responded with alacrity. His flotilla was somewhat scattered, but Vian’s flurry of orders quickly set them on Altmark’s heels. All ships were ordered to intercept the fugitive German vessel at full speed. Intrepid and Ivanhoe, being the closest, had the best chance to overtake her. But would the Altmark give them the slip once again?

The German Quest For Maritime Mastery

The Altmark story had its roots in Germany’s continued quest for wartime mastery of the seas. Britain was an island, dependent on sea trade to maintain itself and its war effort. The world’s sea lanes were Britain’s lifelines. Sever them, and a weakened and starving island nation might sue for peace.

The German panzerschiffe, or pocket battleships, were ideally suited as commerce raiders, sinking Allied merchant ships or capturing them as prizes. Trade would be disrupted, causing possibly critical shortages of food, fuel, and war materiel. The world’s oceans were wide, and the pocket battleship raiders would be hard to locate. They were swift enough to evade pursuers, and if worse came to worse they could fight their way out of trouble with 11-inch main batteries.

The Admiral Graf Spee was considered the most modern of the panzerschiffe, a warship that was the pride of the German Navy. It was commanded by Kapitan zu See (navy captain) Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff, a man ideally suited to the coming mission. A brilliant strategist, he was more than capable of exercising independent command. During the late summer of 1939, it was clear that Europe was heading toward war. There was always a chance that Britain and France would let Hitler have his way with Poland, but the Kriegsmarine decided to take no chances.

Captain Heinrich Dau: Master of the Altmark

On August 21, 1939, Admiral Graf Spee left Wilhelmshaven to take up her station in the South Atlantic. Once hostilities opened, the British were bound to blockade the German coastline as they did in 1914. Langsdorff’s orders were simple and to the point. In the event of war, his main task was the “disruption and destruction of Enemy Merchant Shipping by all possible means.” Above all he was enjoined to “respect neutrality” of nations not likely to join the conflict.

In the age of sail, surface raiders were comparatively independent, but this was not the case with modern warships. Modern vessels need supplies, especially fuel oil and ammunition, if they have any hope of fulfilling their assignments. Admiral Graf Spee was no exception. The German tanker Altmark was the raider’s supply ship, loaded with all the food, ammunition, and diesel oil the pocket battleship would need in the coming months.

Captain Heinrich Dau was the master of the Altmark, a man whose personality was to have a crucial bearing in the events to come. The contrast between Captain Langsdorff and Captain Dau was profound. Langsdorff was a handsome, dapper man in his early 40s, whose immaculate uniform and military bearing proclaimed him a thoroughgoing professional. Dau was 65, his features seamed and weather-beaten from a lifetime at sea. The tanker captain sported an old-fashioned goatee that might have been fashionable in 1914, but here served to conceal a weak chin.

The difference in personality between the two men was even more profound. Dau was a pompous man, much given to lecturing his long-suffering and captive-audience crew. Speeches were often laced with references to the “Führer” and Germany’s glorious “destiny.” His adoration of Hitler and corresponding hatred of the British at times bordered on caricature. When the Graf Spee and Altmark rendezvoused at sea just before the outbreak of war, the first meeting between the two men was correct but strained.

Captain Langsdorff was a man with a deep sense of personal honor and integrity. He was the last of a dying breed, the chivalrous warrior who genuinely believed that war should be tempered with humanity. Dau’s constant mouthing of Nazi slogans and anti-British propaganda grated on Langsdorff’s ears. The tanker captain’s manic ravings notwithstanding, Langsdorff refused to allow the killing of civilians. Once the Graf Spee was refueled and provisioned, the pocket battleship went on its way. For the next three months, the Altmark and Graf Spee would meet on a periodic basis when the panzerschiffe needed supplies.

Captain Langsdorff’s First Victim

The war began in early September, but Langsdorff was not given the green light to begin commerce raiding operations until the 26th of that month. It did not take the resourceful captain long to find his first victim. The initial hunting grounds were the waters off Pernambuco, Brazil, where they encountered the British freighter SS Clement.

The Clement was a 5,051-ton vessel loaded with paraffin from New York. Before fate intervened, Cape Town, South Africa, was to have been its destination. Admiral Graf Spee steamed at full speed, its graceful bow plowing the water into twin whitecaps that dissolved into a powerful wake. Radio messages in English crackled through the airwaves, demanding a full stop and radio silence. The Clement’s Captain F.C.P. Harris complied, but not before getting out an SOS and a full if hurried description of their attacker.

Harris ordered the crew to abandon ship, and soon the Clement’s three lifeboats were manned and ready to depart. Captain Harris chose to remain behind, as befits a ship’s master, accompanied by his chief engineer. The three lifeboats started the long row to Pernambuco as a German prize party from the Graf Spee scrambled aboard. Captain Langsdorff radioed Pernambuco, alerting Brazilian authorities that three boatloads of British seamen were heading their way. It was a chivalrous gesture typical of the man, but it also showed the panzerschiffe captain’s devious side. He made sure the missive was signed “Admiral Scheer,” another of Germany’s pocket battleships.

The Newton Beach, Ashlea and Huntsman

On October 5, the panzerschiffe ran across the SS Newton Beach, a 4,651-ton cargo vessel with a hold full of maize. They were too far out to sea to man the boats, so the crew stayed aboard when a German prize crew took possession. Two days later, on October 7, the Graf Spee scored again with the SS Ashlea, Captain Charles Pottinger commanding. Once again, the hapless victim had little choice but to heave to and let a German boarding party take control.

Captain Pottinger noticed another ship just behind the Graf Spee. It was the Newton Beach, still in German hands. The Ashlea crew was ordered to man their boats and row over to the other British ship. The ill-fated Ashlea was then sunk, disappearing beneath the waves without a trace. Once her destruction was accomplished, the two captured British crews were transferred to the Graf Spee. A day later, Newton Beach met the fate of its sisters.

The SS Huntsman was the next victim of the roving pocket battleship. It was becoming almost routine for the Graf Spee crew, though there were some minor variations to each individual attack. Huntsman was the biggest prize to date, some 8,196 tons and manned by 84 crewmen. The Huntsman was carrying carpets, jute, tea, and tropical equipment from such exotic ports as Colombo and Calcutta.

A day or two later, Admiral Graf Spee met Altmark at their prearranged rendezvous. Dau was ecstatic when he saw the four British flags flying from the pocket battleship, each ensign taken from a captured enemy vessel. A quick conference with Langsdorff deflated Dau’s buoyant mood. The panzerschiffe captain told him that many prisoners had been taken—too many to accommodate on an already-crowded warship.

The Altmark Became An Impromptu Holding Area For Merchant Crews

Langsdorff freely admitted that his original plan to send the captured ships back to Germany was just not practical. The merchant ships did not have enough fuel to get back to Europe, and besides, he could not continue to deplete Graf Spee’s complement by detaching the 25 or so men needed to serve as a prize crew for each captive freighter. No, the British crews of the Ashlea and Newton Beach would have to be held on the Altmark. The Huntman’s crew would soon follow, then their ship too would be destroyed.

Dau was more than appalled. He could scarcely believe his ears. There would be over 150 British prisoners all told, and Dau only had 134 crew members. Acknowledging this legitimate concern, Langsdorff assigned one officer and 10 men from the Graf Spee to guard the prisoners. Eventually, the Huntsman came up and her crew was taken aboard the Altmark.

Altmark was a floating base whose supplies were vital to the panzerschiffe’s continued success. For that reason, Dau exercised the utmost caution, even going so far as to disguise the tanker’s true identity. The Altmark had been painted light yellow from stem to stern, and large letters proclaimed the ship to be the Sogne whose home port was Oslo. The ruse certainly fooled the Huntsman crew, who were briefly elated to be transferred to a “neutral” ship. Hopes of repatriation were dashed when they realized Sogne was really the Graf Spee’s supply vessel.

10-Foot Storage Decks Used As Cells

Some of Huntsman’s crew were Indian, a fact that sparked much excited comment among the Germans. Held in a different compartment from their white comrades, their colorful turbans and strange customs made them a source of endless fascination. Part of the German curiosity stemmed from Nazi ideology, which held that people of color were little better than subhuman.

The British prisoners would be held in a series of four empty storage decks, one on top of the other. Each had a 10-foot ceiling and electric lights, but otherwise were ill-suited for human habitation. The British tars soon dubbed each deck a “flat” (apartment) and tried to make the cold steel holds as comfortable as possible. Ship’s carpenters worked with a will, transforming ammunition boxes into rough tables and chairs. Carpets and jute, salvaged remnants of former cargoes, were made into bedding.

Gradually the men sorted themselves out, and a routine was established. Rations were going to be scanty and would have been even less if Captain Dau had had his way. Dau made no bones about the fact that he hated the British, and told them so repeatedly in red-faced, staccato harangues. There were around 40 to 50 men in each “flat” initially. A trunkway connected the flats and led to the top deck by means of a ladder.

The Sailors’ “Peggy” System

To get their rations the prisoners worked out a rotating “peggy” system. Each deck or “flat” would have its “peggy,” a sailor designated to get the food for himself and all his “roommates.” When a German guard shouted, each peggy would climb up and eventually reach the galley, where rations would be distributed.

The Germans planned the prisoners’ day with typical Teutonic thoroughness. At 7 am the captives would be turned out and led to the wash “flat,” after which they had their meager breakfast. From 8:30 to 9:15, they would be allowed up on the open deck for some coveted fresh air. Filling their lungs with the fresh sea air, so different from the dank stale holds, they would reluctantly go below when the guards told them the time was up. At 5:30 in the afternoon they were allowed some tea, and then lights out at 9 pm.

The prisoners agreed that most of the Germans, though not all, were decent enough. That favorable assessment did not include Captain Dau, however. Rules were strict, and any infractions might mean solitary confinement on a diet of bread and water. Lieutenant Otto Schmidt was the officer in charge of the prisoners, and in consequence they got to know him well. He spoke English, and his youthful looks quickly caused the British to dub him “babyface.” He was friendly enough—within limits. Altmark’s physician, Dr. Tyrolt, gave them adequate enough care, and at times could be sympathetic to their plight. Ironic, in that Tyrolt was actually a member of the Nazi party.

In the meantime, the Graf Spee was the object of one of the most massive hunts in naval history. When word first came of the Clement’s capture, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston S. Churchill responded with alacrity. He was well aware of the enormous threat the German raider posed to British commerce, and was determined to find the ship at all costs. All the might of the Royal Navy was brought to bear in this operation. As Churchill put it, “all available aircraft carriers, supported by battleships, battle-cruisers, and cruisers” from both the Mediterranean and Home fleets would be used in the quest.

The Capture of British Vessels Almost Routine

Captain Langsdorff was well aware of the danger, but proceeded with his mission. The Graf Spee’s next victim was the SS Trevanion, stopped and sunk on October 22, 1939. At first, the captured seamen puzzled over Graf Spee’s seemingly uncanny ability to find targets on such a vast ocean. Then the truth dawned. The panzerschiffe had two scout seaplanes aboard! An onboard catapult would launch a seaplane, whose pilot would find victims and radio their positions back to base. When the pilot returned, a giant crane would lift the seaplane out of the water and back into position on the ship.

By now the capture of British vessels had become almost routine. The Graf Spee would approach the target, usually flying a French flag to lull initial suspicions. Radio messages would crackle across the void, telling the merchantman to stop engines, heave to, and above all maintain radio silence. Ships failing to comply were threatened with dire consequences. In virtually every case the ships did defy Graf Spee and sent out SOS signals that gave details about their attacker.

The Trevanion was no exception, but the moment the ship’s radio operator began to transmit, Graf Spee opened fire. Shells shredded the decks and tore away ladders and pieces of the superstructure, but no one was seriously injured. Eventually, the Trevanion’s crew found themselves locked up with their compatriots aboard Altmark. The mood was turning sour. Captain Dau’s angry anti-British ranting seemed to increase with each new prisoner.

Aboard the Graf Spee, Captain Langsdorff cared little for Dau’s obsessions. He had to plan his next move. It was obvious that the last SOS had been received by the Admiralty and that the Royal Navy was converging on his location in the South Atlantic. He decided on a different tack. He would go to the Indian Ocean.

The Graf Spee’s brief foray into the Indian Ocean was not as successful as its South Atlantic stay. Only one ship, the small motor tanker Africa Star, was taken and sent to the bottom. The pickings were indeed slim, but at this stage Langsdorff did not care about prizes. The main intention of his Indian Ocean foray was a diversion, a means of throwing the British off the scent.

The Royal Navy Gets Tipped Off With a Diversion

Sure enough, when word reached the Royal Navy that the German raider was operating in the Indian Ocean, two hunting groups were dispatched to the area. Force H had the heavy cruisers Sussex and Shropshire, and Force K the battlecruiser Renown and aircraft carrier Ark Royal. They were bound to catch the German raider and put an end to his career—or so it seemed.

Unfortunately for Langsdorff, not all of the British rose to the bait. Commodore Harry Harwood of Force G had a hunch that Graf Spee was going to return to the South Atlantic and elected to remain on station off the River Plate in South America. Force G included the heavy cruisers Exeter and Cumberland and the light cruisers Ajax and Achilles, more than enough firepower to deal with the elusive German.

Harwood’s instincts were sound. By early December, Graf Spee was once again operating in South Atlantic waters. Two more ships had been bagged, the SS Doric Star and the refrigerator ship Tairoa. It was the same old story. The British merchantmen refused to obey demands for radio silence. With the British noose tightening, Langsdorff was beginning to feel the strain. He was still an honorable man, but his irritation at continued British defiance resulted in occasional bursts of temper.

When Tairoa began to transmit, Langsdorff curtly ordered the Graf Spee to open fire. Shells rained down on the helpless freighter, bright blossoms of flame and smoke marking each hit. The ship shuttered and heaved under the impact, and this time there were serious casualties. No one was killed outright, but several were seriously hurt, blood streaming from deeply lacerated wounds. The crew surrendered and was transferred to the already-crowded Altmark; the Tairoa was soon sunk and disappeared beneath the waves.

Prisoners Shuffled Around to Stifle Revolt

Earlier, 27 of the prisoners had been transferred to the Graf Spee, each obviously selected with care. The number included the captains, first officers, engineers, and wireless operators. A few wounded men from the Trevanion were included, and a couple of toothache cases, but for the most part they were all officers or those who might provide prisoner leadership. Fears of a prisoner revolt, or even an attempt at taking over the Altmark, were rising. These transfers were an attempt to defuse the situation.

Graf Spee made its ninth rendezvous with Altmark on December 6, 1939. Langsdorff and Dau had no way of knowing, but it was to be their last meeting. Langsdorff told Dau that Graf Spee’s engines were worn and in bad need of an overhaul after so many months at sea. He was going to ask his superiors if he could head for home. It was agreed that Captain Brown of the Huntsman and Captain Star of the Tairoa would remain on the Altmark.

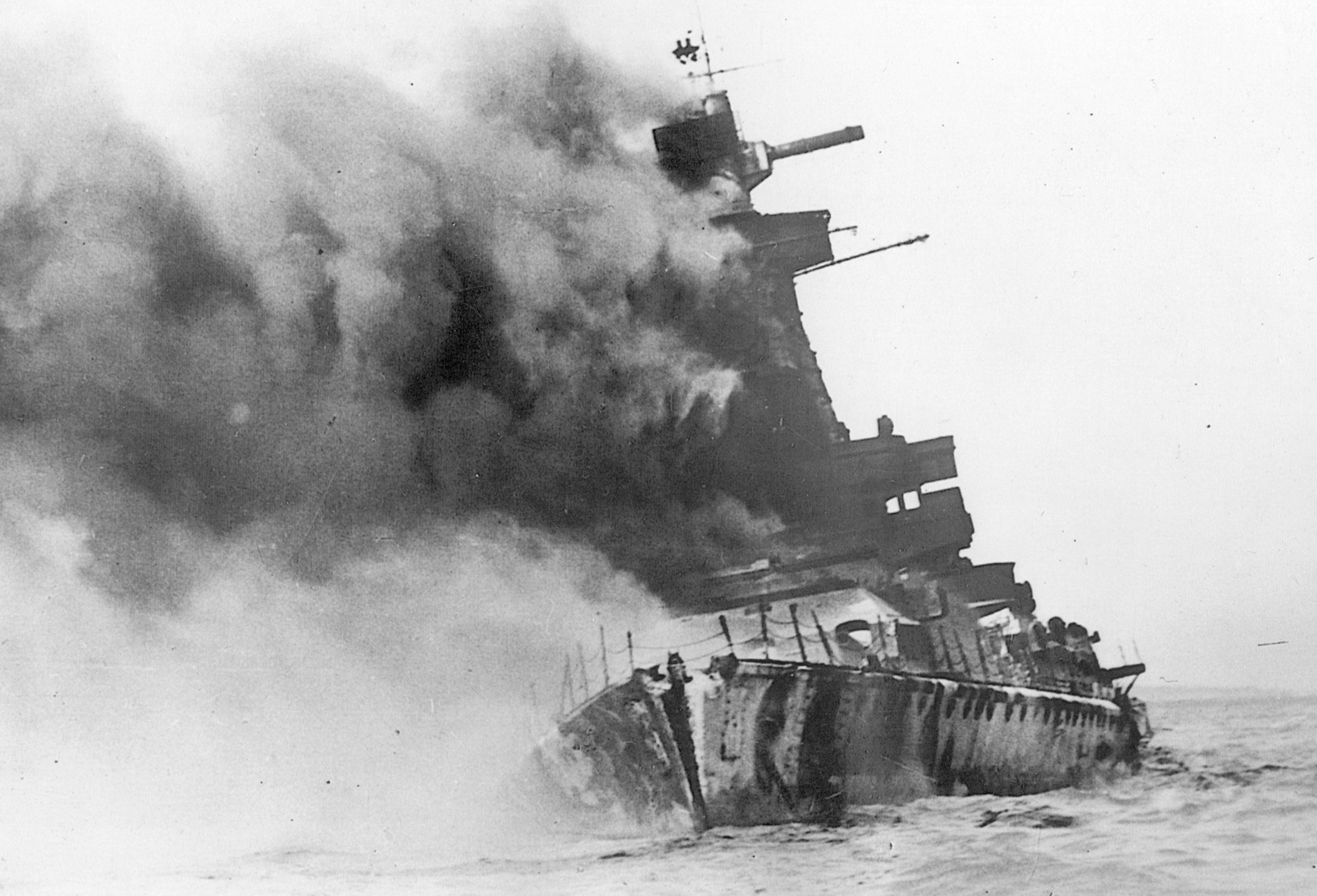

The Graf Spee continued on its way, sinking another merchantman on December 7. It was to prove the raider’s last victim. On December 13, Graf Spee ran into Harwood’s Force G about 150 miles off the River Plate. The British “hounds” had finally brought the elusive German “fox” to bay. The Battle of the Plate pitted the Graf Spee against Exeter, Ajax, and Achilles. The German pocket battleship managed to inflict some heavy damage on its adversaries, but did not escape unscathed.

Langsdorff headed to Montevideo, Uruguay, for repairs. There was a huge six-foot tear in the bows from British shellfire, and the ship had sustained 36 dead and 60 wounded. In retrospect, the decision to sail to Montevideo was a poor one, though Langsdorff had few options. Eventually, Graf Spee was scuttled to prevent her capture by the British. The German crew was interned for the duration, and the lucky 27 British captives released. Captain Hans Langsdorff committed suicide in a possible atonement for the loss of his command.

Conditions Continued to Erode Aboard the Altmark

The Altmark was now truly alone, and the released Graf Spee captives were quick to inform the Royal Navy of the ship and its precious cargo. By this time conditions aboard ship were going from bad to worse. A few weeks earlier, the prisoners’ portable wireless radio sets had been taken away by a spiteful Captain Dau. The radios had been a source of news and entertainment and a fragile link with home. After this, the prisoners’ moods turned sullen and ugly.

Apart from cramped conditions and poor food, the sailors suffered from the sheer boredom of captivity. Their fate was uncertain. The situation was particularly grim for the younger men, sailors accustomed to an active, boisterous life. They had few outlets for their pent-up energy, and fights and scuffles broke out between prisoners.

The Altmark Affair Begins

And so the Altmark affair began, a sequel to the Graf Spee saga but no less compelling. The ship had gone through many incarnations in the past four months. First it had been painted yellow, then sported a yellow funnel, white deck houses, and black top sides. Dau knew that the recently released Graf Spee prisoners would give the Royal Navy a complete description of his fugitive vessel. It was time to call all hands to the paint pots once again. Altmark was painted gray, and also “grew” several gray canvas structures to alter its silhouette. The German tanker was now the Hangsmund.

When the British prisoners heard of the Graf Spee’s demise their emotions ran the gamut from elation to utter dejection. It was obvious the Altmark would be going home, which meant the terrible prospect of continued incarceration in a German internment camp. Chafing at confinement, some of the prisoners suggested they overpower the guards and rush the ship. Surely their roughly two to one advantage over the Germans would favor such a plan. Other prisoners counseled caution.

Prisoners Punished for A Failed ‘Message In A Bottle’

A few of the prisoners decided to try a variation of the old “note in the bottle” ploy. First, a note detailing their plight and the ship’s position was written in block letters. It was then covered in aluminum foil for protection and stuffed in a tin that could float. A tiny Union Jack on a stick was also stuck in as a marker “buoy.” Once again, some captives counseled caution. It was too dangerous. The prisoners managed to secretly toss the note overboard during an exercise period, but it was spotted in the ship’s backwash.

Captain Dau’s reaction was predictably severe. Raging at the “sabotage” of these “English swine” he ordered that open-deck fresh air and exercise periods be halved. It was a severe punishment for men confined to foul holds most of the day.

Altmark was truly becoming a hell ship to the British prisoners. When the soap ration ran out, the captive Britons became ragged and dirty. Conditions on each “flat” were so crowded that the packed bodies and lack of circulating air produced condensation. The steel hold walls, supports, and ceilings “sweated” profusely. Men were constantly wet, and the air was dense and foul with the expelled carbon dioxide of so many lungs. Altmark also ran into a patch of bad weather, which added to the discomfort.

Reaching the North Atlantic

By sheer luck, or so it seemed, Altmark shook off its pursuers and actually managed to reach the North Atlantic. From the German perspective, the tanker was still not out of danger. If anything, crossing the heavily traveled North Atlantic sea lanes increased the risk of discovery. Swinging past Iceland, Altmark made its way into Norwegian waters. If all went well, they would be in Hamburg in a few days. Norway was neutral, so the “innocent merchantman” Altmark need not fear British incursions. The Norwegians did not need to know that they were carrying prisoners in violation of their neutrality.

On the morning of February 14, 1940, the Norwegian patrol boat Trygg appeared and an inspection officer boarded Altmark. Dau insisted his was an “unarmed tanker,” though machine guns and rifles were hidden aboard. The Norwegian officer seemed satisfied and returned to the Trygg. A short time later the patrol boat reappeared, this time with two coastal pilots and, more ominously, a Norwegian naval officer. The officer wanted to have more information on this German intruder. It was approaching the fortified base of Bergen, and Dau was told he could not pass through this area at night.

While he was engaged in animated conversation with the Norwegian, Dau heard a kind of low rumbling from below decks. He politely excused himself and went to see what was the matter. In the holds of the ship the prisoners were creating a terrible din in hopes of attracting the Norwegian’s attention. “All together lads!” cried Tairoa Fourth Officer John Banmant. “Give it all you’ve got!” Men grabbed pieces of wood and hammered on steel plates and stanchions, or banged against the steel drum that served as a lavatory.

A Second Revolt Quelled

The desperate cacophony was muffled, and Dau further masked it by turning on the freight winches. “My ship is empty,” he explained with a disarming grin, “and my crew are cold. The winches generate heat!” The Norwegian returned to the Trygg still ignorant of the British presence. To quell the “revolt,” Dau ordered that the fire hoses be put on the prisoners. Water jets slammed against packed bodies with bruising force, soaking the helpless captives to the skin. The water had overturned the steel drum “lavatories,” creating a terrible stench that permeated every corner of the holds.

As an added punishment, Dau ordered the hold lights to be extinguished, plunging the holds into total darkness. Tiny beams stabbed through the void, light from the one or two flashlights the Germans had failed to confiscate from the prisoners. The darkness matched the all-pervading sense of hopelessness and gloom that gripped the prisoners.

The Altmark proceeded south, its progress briefly impeded by the Norwegian destroyer Gorm. Once again a Norwegian officer boarded the German ship with the announced intention of searching the vessel. Dau resolutely refused, so he was curtly informed to move on immediately.

Churchill’s Orders Were Clear: Find the Altmark and Liberate Her

In the meantime, Captain Vian and his flotilla were ordered to conduct an “ice reconnaissance” of the Skagerrak strait, but their real mission was to find the Altmark. Since the flotilla would be patrolling neutral waters, diplomatic niceties had to be observed. In London, First Sea Lord Churchill’s instructions were as incisive as the man himself: Find Altmark, edge her into the open sea, board her, and liberate her prisoners.

Captain Vian had five destroyers and one cruiser to conduct search operations, but he did not know what the Altmark really looked like. And who knew what flag she might be flying in disguise? A junior officer aboard Cossack triumphantly rushed to the bridge with a copy of the London Illustrated News dated February 4, 1940. The issue carried a photo of the Altmark! It was an incredible piece of serendipity.

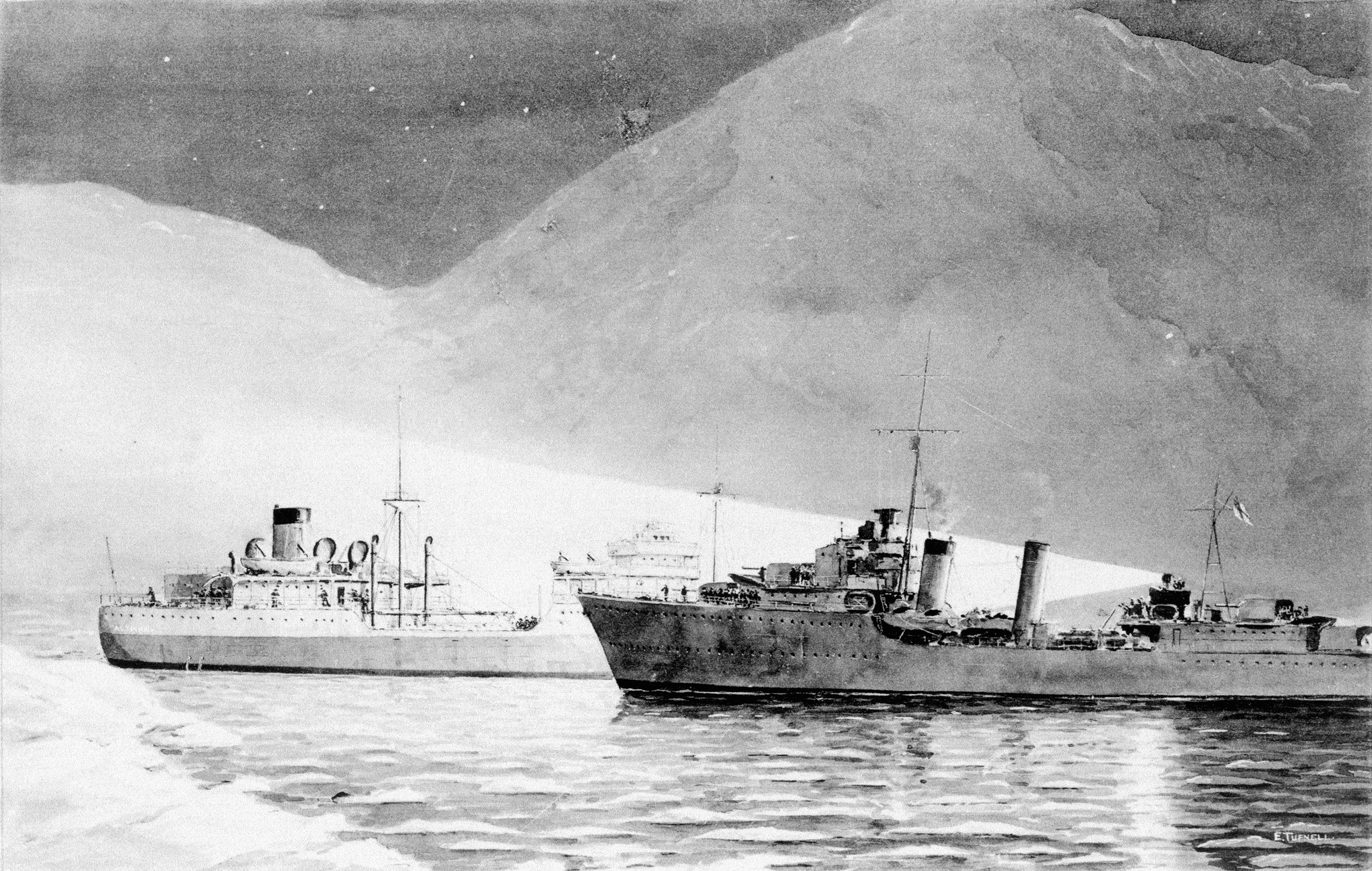

When the air patrol spotted Altmark, Captain Vian swung into action. The cruiser Arethusa and destroyers Intrepid and Ivanhoe were ordered to proceed at full speed. The rest of the flotilla would follow. About 2:45 in the afternoon of February 16, the Altmark spotted ominous silhouettes on the horizon. As the vessels neared, Dau muttered, “Englische Kriegschiffe”—English warships. It was the Arethusa, Intrepid, and Ivanhoe, and the quarry had been found at last.

Altmark was ordered to steer west, that is, sail into the open sea, but the German ignored the summons. Intrepid closed, and a British boarding party readied itself for action. Altmark was also being followed by the new Norwegian gunboat Skarv which, for the moment, seemed to be content merely to observe the unfolding drama. Altmark was now hugging the Norwegian coast, but Intrepid was determined to halt her progress. The British ship tried to put a shot across the German’s bow, but both vessels were maneuvering so rapidly the shell actually hit land.

Trapped Within Norwegian Territory

A British shell had hit neutral Norwegian soil! A major embarrassment, but Intrepid pressed on, firing a second shot that succeeded. Both Altmark and Intrepid jockeyed for position, the Norwegian gunboat playing referee, but with a decided bias in favor of the Germans. Every time Intrepid tried to force its quarry out to sea, the Skarv was in the way.

Finally, Captain Dau headed for the shelter of nearby Jossing Fjord. The waterway was covered by a thin crust of ice, but the Altmark plowed through with little trouble. The German tanker was now well within Norwegian territory and also trapped. A second Norwegian gunboat, Kjell, appeared on the scene, joining the Skarv as small “watchdog” guardians of the coast.

The Altmark affair was creating a diplomatic problem of monumental proportions. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain summoned the Cabinet to discuss the situation, and in Oslo the Norwegian foreign minister was being kept well informed. Adolf Hitler also was watching the unfolding events with keen interest. If the Altmark was an ordinary tanker, then British harassment in neutral waters was illegal. If, however, the German was a prison ship, carrying internees through Norwegian waters was an infringement of international law.

Captain Vian arrived at the scene and conferred with Norwegian authorities. The Norwegians were generally sympathetic to the British, but had to be cautious and correct. They did not want to give Hitler any excuse to invade their country. When Vian radioed for new orders, Churchill told him to offer to help the Norwegians escort the Altmark to Bergen. Once in Bergen, the tanker must be thoroughly searched. If the Norwegians refused, Vian was to board Altmark without further delay.

Dau Orders the “Final Operation”

The Norwegians indicated they would not cooperate, so the Altmark would be boarded. The Cossack nosed into Jossing Fjord at 10 that evening. The fjord was hemmed in by towering peaks and snow-dappled fir trees, the twinkling lights of a few scattered houses giving the scene a “picture” quality.

At first, Dau thought the approaching Cossack was a Norwegian vessel, but when he realized the truth he muttered “final operation.” It was the code for scuttling the ship to avoid its capture. But the wily old captain still had a trick or two up his sleeve. He would get underway and order full astern, using the Altmark’s rear as a giant battering ram. If contact could be made, the Altmark could do serious damage to the Cossack’s thinner steel plates.

Luckily, Vian saw what was happening and neatly sidestepped Dau’s desperate maneuver with superb timing and skill. Altmark did give Cossack a glancing blow, and as the ships closed some members of the British boarding party jumped on the tanker. Lieutenant Commander Bradwell T. Turner was one of those who took the perilous leap, landing heavily on the Altmark’s poop deck. Drawing his revolver, he noticed that Lieutenant “Nosey” Parker was also with him. Rifles at the ready, more of the boarding party followed.

299 Seamen Rescued

A scattering of shots told the British the Germans were not about to give up without a fight. The British returned fire, the Altmark echoing with the sound of guns and the shouts and curses of men scrambling in the darkness. More armed British sailors boarded, and after a brief, sharp fight the ship was taken. “Any Englishmen down there?” the boarding party queried when the hold was open. “Yes, we are all English down here,” was the reply. “Come up, then, the Navy is here!”

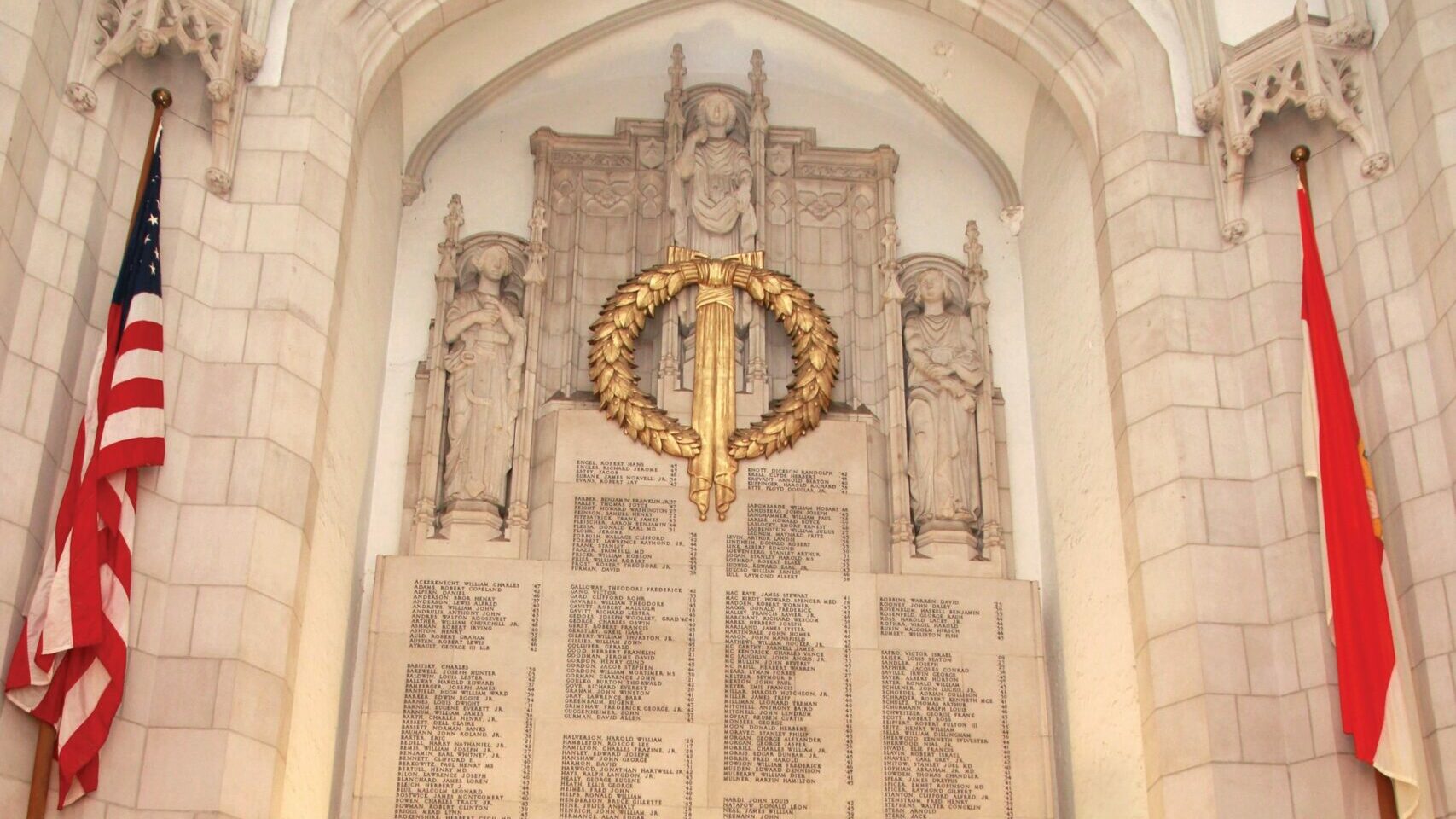

All together 299 British seamen were rescued from the Altmark’s dank holds. Four Germans were killed and four wounded in the operation. Only one member of the boarding party was wounded. Altmark had run aground, though it sustained relatively little damage.

Its mission accomplished, the Cossack withdrew once the liberated prisoners and ship’s personnel were all safely aboard. An exasperated Captain Dau and his crew were left behind since there was no need to take them into custody. Britain was electrified by the news. There had been a lull in the fighting after the fall of Poland, and the Allies were in the grip of a “phony war” malaise. The daring rescue boosted morale.

The Norwegians went through the motions, protesting British “violation” of their territory. If they thought that action would assuage Hitler’s anger, they were mistaken. The Führer already had invasion plans in the works; the Altmark incident merely caused the timetable to be pushed forward.

For the British, the Altmark affair was the satisfying postscript to the Battle of the River Plate. Winston Churchill said it best when he wrote that the rescue proved that the “long arm of British sea power can be stretched out, not only for foes, but also for faithful friends.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments