By Michael D. Hull

When the armistice between France and Germany was put into force on June 25, 1940, the fate of the powerful French Navy—the fourth largest in the world—was of critical importance to the British.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his government dreaded the prospect of the French Fleet falling into enemy hands while Britain stood alone against the Axis powers. The odds were already heavy against the island nation’s main line of defense, the Royal Navy. Facing both the German and Italian navies, it was stretched thinly in the North Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, the Far East, and the Mediterranean Sea.

The terms of the infamous armistice at Compiegne stipulated that the French Fleet would not be used by Germany or Italy, but would be immobilized under their control. Also, the Vichy French naval minister, Admiral Jean Darlan, though no friend of the British, instructed his captains that under no circumstances were their ships to be made available to the Germans. But the British were not aware of the full text of Darlan’s directive and feared that France’s battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines might soon be deployed against them.

Most of the main French naval units were scattered among various Mediterranean ports, while others were in British harbors and the French West Indies. Anchored at the Mers-el-Kebir base in Algeria were the modern 26,500-ton battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg; two aging battleships, the 22,189-ton Bretagne and Provence; the 10,000-ton seaplane carrier Commandante Teste; and six large destroyers. The ships formed the main French naval squadron in the Mediterranean.

In the nearby port of Oran were seven destroyers and four submarines. The new, uncompleted, 38,000-ton battleships Jean Bart and Richelieu were tied up respectively at Casablanca in French Morocco and Dakar in French West Africa, while the aging 22,189-ton battleship Lorraine and four cruisers lay under the guns of the British Mediterranean Fleet in Alexandria harbor.

It was a situation that Churchill and his ministers could not permit, so it was decided that the French Fleet must be put permanently out of Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler’s reach. The prime minister noted that the German government had “solemnly declared” that it had no intention of using the French vessels. “But who in his senses would trust the word of Hitler after his shameful record and the facts of the hour?” said Churchill. He believed that the Compiegne armistice could be voided at any time. “There was in fact no security for us at all,” he said. “At all costs, at all risks, in one way or another, we must make sure that the navy of France did not fall into wrong hands, and then perhaps bring us and others to ruin.”

The solution devised by Churchill and the Admiralty was the hasty creation of a powerful squadron to fill the vacuum left by the French Navy in the Mediterranean, and, if necessary, destroy it. The War Cabinet did not hesitate, Churchill reported later. “Those ministers who, the week before, had given their whole hearts to France and offered common nationhood, resolved that all necessary measures should be taken,” said the prime minister. “This was a hateful decision, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned. It recalled the episode of the destruction of the Danish Fleet in Copenhagen harbor by Nelson in 1801; but now the French had been only yesterday our dear allies, and our sympathy for the misery of France was sincere. On the other hand, the life of the state and the salvation of our cause were at stake. It was Greek tragedy. But no act was ever more necessary for the life of Britain and for all that depended upon it.”

So, Force H was formed at Gibraltar on June 28, 1940. Code-named Operation Catapult, its mission was a painful and distasteful one—to neutralize or destroy the French Fleet in the Mediterranean.

Though based at the British bastion guarding the western entrance to the strategic Mediterranean, Force H was to be an independent operational command. The squadron comprised the 22,000-ton carrier HMS Ark Royal; the 42,100-ton battlecruiser Hood; two battleships, 29,150-ton Resolution and 30,600-ton Valiant; the cruisers, 5,220-ton Arethusa and 7,550-ton Enterprise; and the screening destroyers Faulknor, Foxhound, Fearless, Forester, Foresight, Escort, Keppel, Active, Wrestler, Vidette, and Vortigern. Force H was then the main Allied task force in the Atlantic and western Mediterranean.

The first commander was trim, square-jawed, 57-year-old Vice Admiral Sir James F. Somerville, a descendant of the famous Hood naval family. He flew his flag in HMS Hood, which between the wars had been revered as the most powerful ship afloat and the symbol of British naval might.

A decorated veteran of the ill-fated Dardanelles campaign in World War I, Somerville had been invalided out of the Royal Navy with tuberculosis in 1938. Recalled to service at the outbreak of war in September 1939, he helped Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay organize Operation Dynamo, the epic evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk in June 1940. Somerville was regarded by Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, as “a great sailor and a great leader.”

Operation Catapult was launched on July 3, 1940. That night, more than 200 French vessels in British ports, most of them anchored at Portsmouth and Plymouth, were impounded. The ships included the battleships Courbet and Paris, the supply ship Pollux, destroyers, minelayers, minesweepers, submarines, submarine chasers, motor torpedo boats, tugs, trawlers, sloops, and harbor craft. The action was sudden, and overwhelming force was used.

The transfer was amicable, and the French crews came ashore willingly, Churchill reported. However, there were scuffles during the transfer of the destroyer Mistral and the 3,250-ton submarine Surcouf. Two British officers were wounded, a leading seaman killed, an able seaman wounded, and a Frenchman killed. “But the utmost endeavors were made with success to reassure and comfort the French sailors,” said Churchill. “Many hundreds volunteered to join us. The Surcouf, after rendering distinguished service, perished on February 19, 1942, with all her gallant French crew.”

On July 3, 1940, Force H was dispatched to Mers-el-Kebir. There, Admiral Somerville was to open negotiations with Admiral Marcel Gensoul, commander of the French squadron. Gensoul would refuse initially to meet with Somerville’s emissary, and the negotiations were conducted in writing.

The Admiralty had drafted four options for the French admiral: (1) to put to sea and join forces with the Royal Navy; (2) to sail with reduced crews to British ports, where the vessels would be impounded and their complements repatriated; (3) to sail with reduced crews to the base at Dakar, where the ships would be immobilized; or (4) to scuttle his ships within six hours. The Admiralty had instructed Somerville that should Gensoul refuse all of the offers, the French ships were to be put out of action in their present berths, using “all means at your disposal.”

Early on the morning of July 3, 1940, with the sea calm and a warm haze in the air, Force H steamed toward the Algerian coast. The 15-inch guns of Hood, Resolution, and Valiant were trained fore and aft, and Admiral Somerville hoped that they would not have to be fired that day in the fulfillment of his task. He blanched at the prospect of killing French sailors, who were comrades in arms of the Royal Navy. On the evening of July 2, Somerville had received a message from Prime Minister Churchill, relayed by the Admiralty, telling him, “You are charged with one of the most disagreeable and difficult tasks that a British admiral has ever been faced with, but we have complete confidence in you and rely on you to carry it out relentlessly.”

At 9:10 am on July 3, the British squadron arrived off Oran and Mers-el-Kebir. Despite the morning haze, “the upper works of the French heavy ships were clearly visible over the breakwater,” reported Somerville, “although only the actual tops and masts could be seen from a position northwest of the fort (guarding the entrance to the base).” His French-speaking emissary, Captain C.S. Holland, a former naval attaché in Paris, had gone ahead aboard the destroyer HMS Foxhound to rendezvous with Admiral Gensoul’s flag lieutenant outside the Mers-el-Kebir defensive boom.

Captain Holland was met at 8:10 am by Gensoul’s barge bearing his flag lieutenant, “an old friend of mine,” the British officer reported. The French admiral refused to meet with Holland, so the flag lieutenant delivered the British War Cabinet’s ultimatum to Gensoul in his flagship, Dunkerque. “At this point,” recorded Holland, “it was observed that the battleships were furling awnings and raising steam.”

Now, as the day grew hotter, Admiral Somerville could only steam back and forth outside Mers-el-Kebir and Oran, waiting anxiously for Captain Holland to signal back reports on the progress of his negotiations with the French. Two and a half hours passed while Holland, Admiral Somerville, and the War Cabinet in distant London all waited for Admiral Gensoul’s response. It was a tense, impotent time, particularly for the Force H commander.

At noon, Somerville signaled the Admiralty that he would give Gensoul until 3 pm to reply to the British terms. Half an hour later, Somerville was signaled that if he thought the French ships were preparing to leave the harbor, he “should inform them that if they moved, he would open fire.” The Force H commander then signaled to Holland and asked if he thought there was now any alternative to bombarding the French squadron. The emissary urged that the French should be asked for a final reply before any hostile action was taken. Holland told Admiral Somerville that his knowledge of the French character suggested “an initial refusal will often come around to an acquiescence.” Holland said he “felt most strongly that the use of force, even as a last resource, was fatal to our object.” So, he used “every endeavor to bring about a peaceful solution.”

At last, around 3 pm, Admiral Gensoul agreed to meet Holland on board Dunkerque, and this encouraged Somerville to again postpone action. “I think they are weakening,” he signaled to the Admiralty. At 4:15 pm, Holland was piped over the side of the French flagship and ushered into Gensoul’s cabin. The admiral was angry and indignant and had come to believe that the British might actually use force against his squadron. He played for time; British decrypts of French cipher traffic that afternoon revealed that Gensoul could expect support from other naval units and was to “answer fire with fire.” Passing the intercept on to Admiral Somerville, the Admiralty added, “Settle this matter quickly, or you may have reinforcements to deal with.”

Somerville awaited news from Captain Holland, who was now convinced “we had won through and he [Gensoul] would accept one or other of the proposals.” But Holland was unaware of what London had omitted to pass on to Somerville. Its decrypt of the French Admiralty signal to Gensoul indicated that he believed he had only two options: to join the British squadron or scuttle his ships. The tension mounted as the situation came to a head.

Around 5:15 pm, as Gensoul was deciding to reject the British ultimatum, he received a signal from Admiral Somerville stating that Force H would sink his ships unless he accepted the terms by 5:30. The dejected Holland observed that the French battleships were in “an advanced state of readiness for sea.” Control stations were being manned, rangefinders were trained on Force H, and tugs were fussing round the sterns of the French battlewagons. Action stations was sounded, but there was little bustle among the crews, Holland noted. He took a “friendly” leave-taking from Dunkerque as he made his way back to HMS Foxhound. The officer of the watch aboard the battleship Bretagne saluted him smartly. It seemed to Captain Holland that the French could not believe that they were about to be the targets of British gunners. At 5:55 pm, HMS Foxhound got clear after laying magnetic mines across the entrance to Mers-el-Kebir harbor.

Then the dreaded hour of reckoning came as the battlecruiser Hood steamed at 17 knots ahead of Admiral Somerville’s line. Her eight 15-inch guns thundered at a range of 17,500 yards, closely followed by those of Resolution and Valiant. It was the first clash of battle fleets in World War II, but hardly the kind of engagement expected by Admiralty planners in the prewar years; the enemy was not the German, Italian, or Japanese fleets. By a fateful, tragic irony, Force H was attacking the Royal Navy’s 18th- and 19th-century foe and 20th-century ally.

Because of haze and smoke billowing from the French ships raising steam, the targets of Force H were obscured. Hood’s target, a Dunkerque-class battleship anchored abeam to the harbor mole, was indistinct. So the three British capital ships had to use the nearby Mers-el-Kebir lighthouse as an aiming mark and make “a general shoot into the area of the anchorage.” It was difficult for the British crews to observe the results of their volleys, but a Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber from No. 810 Squadron aboard HMS Ark Royal reported from an altitude of 7,000 feet that Hood’s first salvo had exploded in a line across Commandante Teste, Bretagne, and the quarterdeck of Strasbourg.

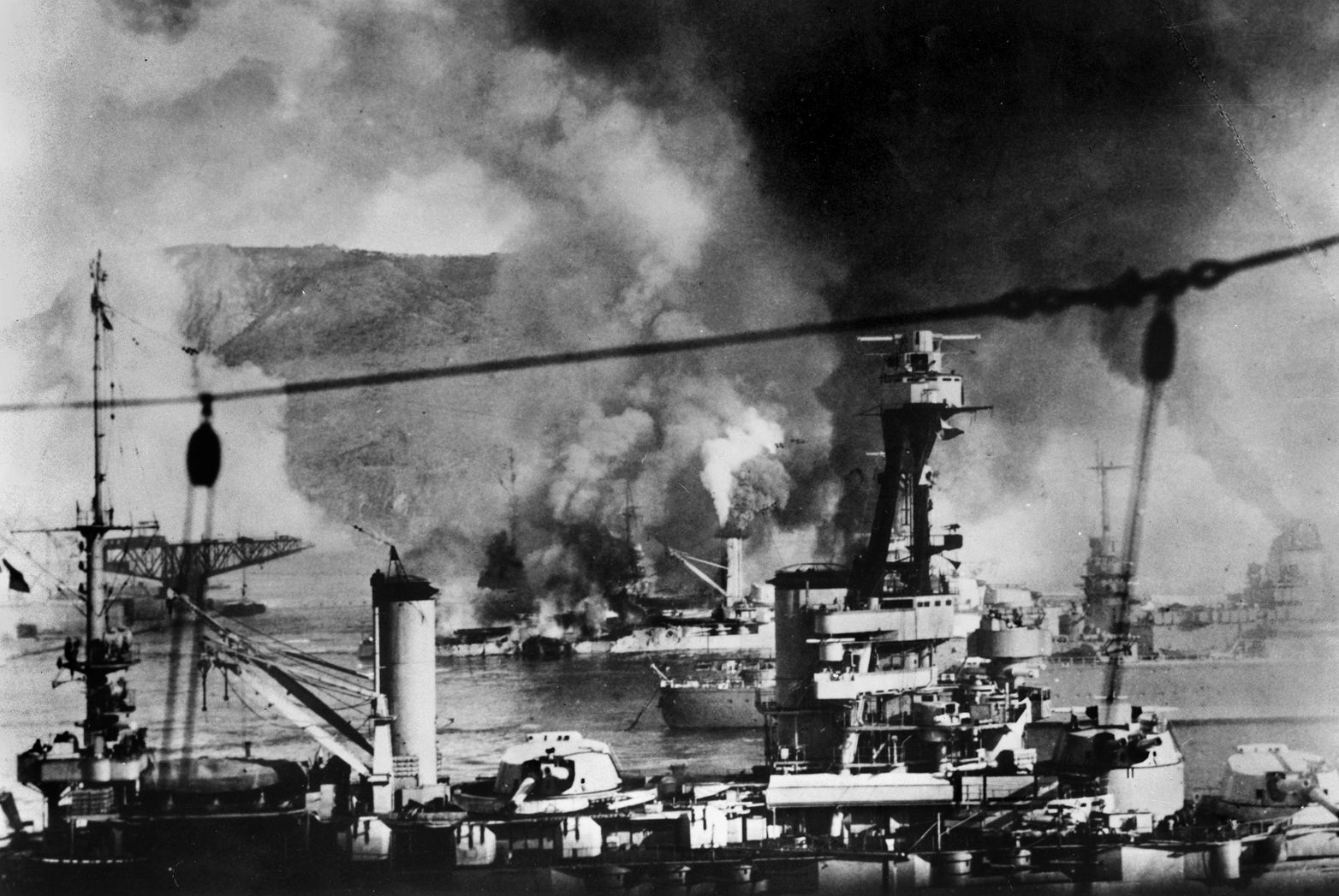

The second salvo, according to the Swordish crew, “hit the Bretagne, which blew up immediately and enveloped the harbor in smoke.” Hit in her after magazines, the French battleship died at 5:58 pm, with a thick mushroom cloud of smoke rising high behind the breakwater. When the smoke cleared, Bretagne was no longer visible to the Swordfish crew, but they observed a fire aft on the seaplane carrier. Dunkerque appeared to have hit a mine, with the loss of 210 dead, and grounded her bows on the shore opposite her berth. It was learned later that the badly damaged Provence also had beached herself. Meanwhile, a direct hit blew off the stern of the large destroyer Mogador, killing 42 men.

Cornered in confined waters and with limited fields of fire because of neighboring vessels, the French warships fired back as best they could. With a crushing 10-minute bombardment, Force H had struck a grievous blow against Gensoul’s squadron. At 6:04 pm, Admiral Somerville ordered a cease-fire in to give the French sailors an opportunity to leave their ships in the smoking harbor. By this time, more than 1,250 seamen lay dead, 977 of them in Bretagne. The cease-fire was welcomed in the British capital ships, where temperatures in the magazines and shell rooms had risen to more than 90 degrees, adversely affecting the crews.

At 6:20 pm, HMS Hood received a signal from the Ark Royal Swordfish crew saying that the battleship Strasbourg and five escorting destroyers had left the Mers-el-Kebir harbor and were heading along the coast. When the report was confirmed at 6:30, Admiral Somerville ordered Hood to steer eastward in pursuit. The British battlewagon increased speed to 25 knots in an attempt to challenge Strasbourg, but then veered away to avoid a torpedo attack by the French destroyers. Somerville, who had decided against a night action, reported later that his Operation Catapult instructions “did not make sufficient provision for dealing with any French ships that might attempt to leave harbor.”

But Force H had not finished with Strasbourg, and six lumbering Swordfish torpedo bombers from Ark Royal went after her. At 8:55 pm, they approached the French battleship at a height of 20 feet (????) and loosed their torpedoes into a calm sea. The Swordfish crews believed that they might have scored two or three hits, but Strasbourg was able to steam away in the darkness and eventually reach haven at the big Toulon naval base in southeastern France.

Three days later, early on July 6, 1940, Swordfish planes from Ark Royal flew back to Mers-el-Kebir to finish off the grounded Dunkerque. Diving out of the rising sun from an altitude of 7,000 feet, the “stringbag” biplanes dropped six torpedoes, sinking the 859-ton auxiliary ship Terre Neuve, berthed alongside the battleship. The supply ship’s cargo of depth charges exploded, ripping open the side of Dunkerque. Another 150 French sailors were killed. Meanwhile, Force H was also battling surface units and submarines of the Italian Fleet elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

On July 7, the British turned their attention to the French naval base at distant Dakar in West Africa, where the battleship Richelieu, cruiser Primauguet, a sloop, and destroyers were anchored. Commanded by Captain R.F.J. Onslow, a small force comprising the 10,850-ton carrier HMS Hermes and the cruisers Australia and Dorsetshire stood off the harbor. Onslow was given an Admiralty ultimatum for the French, similar to that given at Mers-el-Kebir, but the commander of the Dakar squadron refused entry to a sloop carrying a Royal Navy emissary.

During the night of July 7-8, a fast launch from Hermes sneaked through the harbor booms, dropped depth charges under the stern of Richelieu, and escaped. The charges failed to detonate, but three hours later six Swordfish from the British flattop pounced on the battleship. They achieved only one hit but distorted a propeller shaft and flooded three compartments.

At Alexandria, meanwhile, Admiral Cunningham was able to persuade the French squadron there to disarm, avoiding more bloodshed. Its fuel and ammunition were surrendered to the Royal Navy. On July 18, all French merchant ships in the Suez Canal were seized.

The British had largely eliminated the French Navy as a strategic factor in the war, and it was, said Prime Minister Churchill, “the turning point in our fortunes.” Inevitably, the clash at Mers-el-Kebir created lingering tension and bitterness between the two nations, even as Free French soldiers, sailors, and airmen were rallying to General Charles de Gaulle and the Allied cause. Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain’s Vichy government broke off diplomatic relations with Britain and moved closer to active collaboration with Germany, and French planes dropped a few retaliatory bombs on Gibraltar. Vichy resistance to the British and Free French in North Africa and Syria stiffened.

But the Royal Navy’s actions had made clear to the world—and in particular to America, which recognized the Vichy regime—that Britain, on the apparent brink of defeat, was determined to win the battle of the Mediterranean and secure eventual victory.

On the afternoon of July 4, 1940, as his country braced for a possible invasion and imminent major aerial assaults, Prime Minister Churchill spoke for an hour in the House of Commons on “the measures we had taken” to remove “the French Navy from major German calculations.” The House was silent during his recital, but at the end he received a standing ovation. All members, Churchill reported, “joined in solemn stentorian accord.”

He declared later, “The elimination of the French Navy as an important factor almost at a single stroke by violent action produced a profound impression in every country. Here was this Britain which so many had counted down and out, which strangers had supposed to be quivering on the brink of surrender to the mighty power arrayed against her, striking ruthlessly at her dearest friends of yesterday and securing for a while to herself the undisputed command of the sea. It was made plain that the British War Cabinet feared nothing and would stop at nothing. This was true.”

Churchill noted, “The genius of France enabled her people to comprehend the whole significance of Oran, and in her agony to draw new hope and strength from this additional bitter pang.”

He was touched by a story about the aftermath of the July 3 destruction of the French squadron. “In a village near Toulon dwelt two peasant families, each of whom had lost their sailor son by British fire at Oran,” related the prime minister. “A funeral service was arranged to which all their neighbors sought to go. Both families requested that the Union Jack should lie upon the coffins side by side with the Tricolor, and their wishes were respectfully observed. In this we may see how the comprehending spirit of simple folk touches the sublime.”

After the fateful actions at Oran, Mers-el-Kebir, and Dakar, Force H was active in both the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Led by Vice Admiral Sir Neville Syfret and then Vice Admiral Algernon U. Willis after Somerville departed early in 1942, the task force took part in the dramatic pursuit and destruction of the 42,000-ton German battleship Bismarck, the invasions of Madagascar, northwest Africa, and southern Europe, and provided the main escort for vital convoys to Malta. Its fighting strength fluctuated, but the ships most associated with Force H were Ark Royal, the 32,000-ton battlecruiser Renown, and the 9,100-ton heavy cruiser Sheffield. Force H was disbanded in October 1943, when Allied naval supremacy in the Mediterranean Theater was no longer in dispute.

Most of the remaining French Fleet had been scuttled at Toulon on November 27, 1942, following the Allied invasion of North Africa, to prevent its seizure by Germany after the Nazi takeover of Vichy France.

The initial commander of Force H, Admiral Somerville, was knighted in 1941 and appointed commander in chief of the Royal Navy’s hastily created Eastern Fleet in the Indian Ocean in February 1942. Acknowledged as a highly successful surface commander, he served until August 1944, when he was replaced by Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser. Somerville then headed the Admiralty mission in Washington. He was promoted to admiral of the fleet in May 1945 and died in 1949.

Michael D. Hull is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments