By Christopher Miskimon

Many consider the War of 1812 to have been a war the United States should never have waged. America was in over its collective head, and it was lucky to have ended the conflict without suffering defeat. Others believe the war ultimately led to a greater sense of American identity. Both may be true, but it cannot be denied that the war gave us tales of valor which became part of the American lexicon: Fort McHenry, Battle of New Orleans, and the numerous ship-to-ship duels of the fledgling U.S. Navy. The Battle of Stonington: Torpedoes, Submarines and Rockets in the War of 1812 (James Tertius de Kay, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 216 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $26.95, softcover) is a story full of courage equal to those larger tales, although most have never heard of the town or the battle fought there.

Stonington, Connecticut, is a small coastal village less than a dozen miles east of the mouth of the Thames River and New London. A typically small seaport in the early 1800s, it would seem an unlikely place to become the focus of a Royal Navy attack in the summer of 1814. Exactly how that happened and why is the focus of this book. The author does an excellent job of explaining it.

In 1814, the war was largely stalemated along the Canadian border. Each side had variably won or lost, but the overall American goal of invading Canada had failed. Likewise, the British-Canadian forces arrayed against the Americans lacked the ability to carry the war back across the border and inflict a decisive defeat. However, the war in Europe against Napoleon was drawing down, freeing British resources for action against the upstart Americans. While the effect of this would culminate later in the attacks against Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and New Orleans, in the meantime the pressure on the Canadian border needed relief.

To accomplish this, a number of raids and bombardments along the New England coast were planned. Here the British played on American politics and weaknesses. Most of the American troops were militia, tied to their homes and livelihoods. Attacks along the coast would make the civilian populace cry for the return of their militias for local defense. Given the political nature of the militia leadership, this seemed a likely result. New England was also known as a hotbed of opposition to the war since the people there had many business ties to England and Canada during peacetime. A secondary motive for the raids was retaliation for American experiments with submarines and torpedoes against British ships, a threat they considered an unethical way to conduct warfare.

Tiny Stonington was singled out for such a raid. In command was Commodore Thomas Hardy, a close friend of the famed British Admiral Horatio Nelson. They had fought together at Trafalgar, and Hardy was with Nelson when he died. Under Hardy’s command were five ships with a total of more than 160 cannon, along with Congreve rockets. Arriving off Stonington on August 9, 1814, the British sent a note ashore telling the townsfolk to evacuate because the town was about about to be destroyed. Shocked by this, the townspeople decided to fight back with all at their disposal: two 18-pounder cannon and a six pounder.

The battle itself lasted several days, interspersed with truces and negotiations. The Americans were able to inflict considerable damage on their opponents despite their lack of armament, while the British bombardment did only moderate damage to the town. The lack of British success may be more attributed to Hardy’s essential decency; he seemed unwilling to inflict civilian casualties and went to lengths to avoid doing so.

At the time, the battle was national news in America, a stirring tale of victory against overwhelming odds. Largely forgotten today, it is still a good story. The author tells it in a flowing narrative, which entertains the reader as it details the complexities of the battle and the larger picture of the war.

General Douglas MacArthur is a controversial figure to many. Some revere him as a military genius, while others consider him an egotist, more politician than general. Although his accomplishments must be acknowledged, the end of his career was bathed in quarrel as he entered into a dispute with U.S. President Harry Truman. The subject of this clash was no less than a challenge to the Constitution of the United States, whether a military officer could dictate national policy in defiance of civil authority. MacArthur’s War: The Flawed Genius Who Challenged the American Political System (Bevin Alexander, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2013, 248 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover) delves into the conduct of the Korean War under Douglas MacArthur leading to his dismissal by Truman on April 11, 1951.

General Douglas MacArthur is a controversial figure to many. Some revere him as a military genius, while others consider him an egotist, more politician than general. Although his accomplishments must be acknowledged, the end of his career was bathed in quarrel as he entered into a dispute with U.S. President Harry Truman. The subject of this clash was no less than a challenge to the Constitution of the United States, whether a military officer could dictate national policy in defiance of civil authority. MacArthur’s War: The Flawed Genius Who Challenged the American Political System (Bevin Alexander, Berkley Caliber, New York, 2013, 248 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover) delves into the conduct of the Korean War under Douglas MacArthur leading to his dismissal by Truman on April 11, 1951.

The fact that MacArthur was a skilled and competent general was largely borne out by his handling of the response to the North Korean invasion of South Korea. The landing at Inchon along with the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter quickly reversed the tide of the war until Chinese intervention. However, his hardline stance toward China and apparent desire for war with that nation were in direct defiance of the president’s policy of containment of communism and wider concern about not only China, but also the Soviet Union. It was a difficult process for Truman, as MacArthur was popular with the average American and had powerful backers in Congress. In the end, the threat his actions posed to the nation’s democratic civil institutions was too great to allow him to continue wearing the uniform.

The conquest of the Native American tribes by the United States was a long, bitter struggle encompassing a series of wars over several centuries, if one includes the colonial period. Native American warriors were among the best light infantry in the world, and overcoming their resistance to the inexorable westward advance of the American settlers was not always assured. In the years after the Revolutionary War, various tribes fought against the settlement of their lands in the Northwest Territory. Eventually the problem became acute enough that the U.S. Army was sent to deal with it. Fallen Timbers 1794 (John F. Winkler, Osprey Publishing, Botley, Oxford, UK, 2013, 96 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $21.95, softcover) describes the battle wherein that army won its first victory against an alliance of various tribes and secured the area for American expansion.

The conquest of the Native American tribes by the United States was a long, bitter struggle encompassing a series of wars over several centuries, if one includes the colonial period. Native American warriors were among the best light infantry in the world, and overcoming their resistance to the inexorable westward advance of the American settlers was not always assured. In the years after the Revolutionary War, various tribes fought against the settlement of their lands in the Northwest Territory. Eventually the problem became acute enough that the U.S. Army was sent to deal with it. Fallen Timbers 1794 (John F. Winkler, Osprey Publishing, Botley, Oxford, UK, 2013, 96 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $21.95, softcover) describes the battle wherein that army won its first victory against an alliance of various tribes and secured the area for American expansion.

Raiding and sporadic warfare were features of the dangerous life on the frontier during this period. Since they excelled at this kind of fighting, the native warriors were often successful. The U.S. Army, at that time known as the Legion of the United States, was sent west to deal with them, commanded by General Anthony Wayne.

The situation was even more complex, though. British support for the tribes was widespread, the Spanish and French were agitating, and Wayne faced intrigue from within his own ranks as some of his officers schemed and plotted toward their own ends, at times even actively sabotaging the army’s logistics. Wayne had to manage all these complexities during the campaign while preparing to fight an alliance of numerous tribes gathering against him. These tribes assumed another American war with Britain was imminent, and they would drive their enemy out with British soldiers alongside them. When Wayne’s army met those warriors and defeated them in two hours of battle at Fallen Timbers, it was a blow that brought a temporary peace and set the stage for the next round in the early 1800s.

Only in the last two centuries has military medicine made the great leap forward to the cutting edge of medical experience. Only in the last 100 years have armies lost more soldiers to combat than to disease. Between Flesh and Steel: A History of Military Medicine from the Middle Ages to the War in Afghanistan (Richard A. Gabriel, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2013, 300 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover) chronicles the long history of medical coverage on the battlefield.

Only in the last two centuries has military medicine made the great leap forward to the cutting edge of medical experience. Only in the last 100 years have armies lost more soldiers to combat than to disease. Between Flesh and Steel: A History of Military Medicine from the Middle Ages to the War in Afghanistan (Richard A. Gabriel, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2013, 300 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover) chronicles the long history of medical coverage on the battlefield.

The book begins with an overview of the emergence of modern warfare as it developed from feudal times to the War on Terror, focusing on the ever increasing lethality of weaponry. Afterward the chapters launch into the corresponding expansion of military medical services. Beginning with the barber surgeons of the Renaissance and continuing through to the doctors now serving in the Middle East and elsewhere, this book highlights the effort to save lives even as war makes it easier to take them.

Central Europe has long been a pivotal place in world history. Events there and the struggle for control of that region have had ripple effects not only in Europe itself, but also across the globe as the powers that rose and fell there extended their influence to other continents. It began with the Holy Roman Empire and has continued to the present day with the various states which have succeeded it. Even peripheral nations such as Britain and the United States across the Atlantic paid attention to the powers at the heart of the continent as part of their own policies because what happened in the core of Europe was of critical importance.

This is the premise of Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy from 1453 to the Present (Brendan Simms, Basic Books, New York, 2013, 690 pp., notes, index, $35.00, hardcover). Not strictly a military history, the book weaves together political, economic, religious, international, and military events, which shaped the region and made it so important in world history.

This is the premise of Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy from 1453 to the Present (Brendan Simms, Basic Books, New York, 2013, 690 pp., notes, index, $35.00, hardcover). Not strictly a military history, the book weaves together political, economic, religious, international, and military events, which shaped the region and made it so important in world history.

From its beginnings as a fragmented web of independent states which became the Holy Roman Empire, Europe went through a continuing process of political and military amalgamation as various nation-states vied for control. This included decisions on whether to assimilate religious minorities such as the Jews or to exclude and in some case eliminate them. Catholics versus Protestants, royalty against commoner, and Nazi against Communist were all continuations of this fight to unite Europe under essentially a single flag. The situation after the recent economic crisis is characterized as a resurgent Germany attempting to use its wealth to increase its control of the rest of the continent by providing financial aid to nations it has made into markets for its products.

The entire process was aided by an essentially democratic ideology, which permeated European society since the Middle Ages. Unlike nation-states elsewhere, which were ruled despotically, in Europe there was an understanding that the monarch did not have absolute power. While not true democracies, there was a sense of freedom for at least some, and when tyrannical rulers arose they were often deposed by a coalition of princes or nations which recognized the threat they posed.

Memoirs of the Vietnam War are becoming more common than those of World War II veterans, who sadly are now mostly gone. The generation of Baby Boomers who fought in Vietnam is now reaching retirement age, so it is to be expected that more will begin sharing their experiences. Outside the Wire: Riding with the “Triple Deuce” in Vietnam, 1970 (Jim Ross, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 293 pp., maps, illustrations, glossaries, $24.95, hardcover) is among the newest of such memoirs. It relates the experiences of the author as a mechanized infantryman in the 25th Infantry Division as America’s involvement in the war was slowly winding down with the advent of “Vietnamization.”

Memoirs of the Vietnam War are becoming more common than those of World War II veterans, who sadly are now mostly gone. The generation of Baby Boomers who fought in Vietnam is now reaching retirement age, so it is to be expected that more will begin sharing their experiences. Outside the Wire: Riding with the “Triple Deuce” in Vietnam, 1970 (Jim Ross, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 293 pp., maps, illustrations, glossaries, $24.95, hardcover) is among the newest of such memoirs. It relates the experiences of the author as a mechanized infantryman in the 25th Infantry Division as America’s involvement in the war was slowly winding down with the advent of “Vietnamization.”

While the book is overall similar to other veterans’ writings, Ross does an excellent job of recounting the everyday experiences of the infantryman. Rather than fill the book with descriptions of combat, the narrative follows reality; engagements were few and far between, interspersed with at times mind-numbing routines. Guard duty, unproductive patrols, false alarms, and sandbag filling give the reader a feel for what an enlisted soldier did on a daily basis. Added to this is the feeling of near helplessness as the unit moves and acts under the orders of distant officers, orders which seemed incomprehensible to enlisted men.

Descriptions of the combat that did occur are vivid. The litter of shell casings, the noise, and the mixed emotions of fear and anger are all there. An officer’s memoir will usually give background information, the how and why of an operation. As an enlisted man, Ross knew none of this and thankfully did not try to find it for inclusion. How he experienced the war is exactly how it is presented. This microcosm view of the war is how infantrymen before and since have known combat, and that view is well represented here.

With his unit being withdrawn from Vietnam and going home en masse, Ross was dealt a hard blow. Everyone in the unit with 90 days or less remaining on their tour went home; those with more went to another unit. Ross had 93 days left. Sent to the 1st Cavalry Division, he ended his tour as a straight-leg infantryman and then did a short stint in a rear area before going home.

The origins of World War I are generally credited to the series of alliances, diplomacy, and militarism of the major European powers set in motion by the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Serbia on June 28, 1914. Typically, the bulk of blame is placed on the German and Austro-Hungarian regimes. July 1914: Countdown to War (Sean McMeekin, Basic Books, New York, 2013, 461 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover) puts forward a different assessment of the events which precipitated World War I.

The origins of World War I are generally credited to the series of alliances, diplomacy, and militarism of the major European powers set in motion by the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Serbia on June 28, 1914. Typically, the bulk of blame is placed on the German and Austro-Hungarian regimes. July 1914: Countdown to War (Sean McMeekin, Basic Books, New York, 2013, 461 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover) puts forward a different assessment of the events which precipitated World War I.

The author begins with a detailed account of the day Ferdinand died. There were a number of conspirators placed at different locations along the Archduke’s route, which was publicly known. Only a single assassin had to succeed and one did. This was interpreted by the Austrians as an act of war by Serbia, though some Austro-Hungarian elements opposed this stance. Indeed, Austria-Hungary was then regarded as a weak empire by many, unworthy of much consideration.

Still, imperial action against Serbia might draw in the small nation’s nominal champion, Russia. Although the Russian Army was itself not particularly feared abroad, it was more than a match for Austrian strength. This set the Austrians to seek alliance with Germany to counter Russia. From there began the series of events that led to war as one nation after another was drawn into the vast complicated network of European alliances.

Where this work differs from others is in the assertion that the wave of double-dealing, belligerency, and occasionally outright ignorance during July 1914, was spread among what would become the Allied powers as well. In particular France and Russia acted in ways which pushed Europe into conflict, seeking to gain from the political situation after the assassination and seemingly unaware of the wider risks their actions prompted. By the end of July, Europe and the world were set on a path, the consequences of which still reverberate today.

At least technically, the Korean War has never ended. This is brought home occasionally by North Korean saber rattling and the periodic exchanges of fire that still occur between the two Koreas. Yet, since the end of the actual Korean War in 1953, there has been little written in the intervening 60 years to bring the unhappy history of the two Koreas into a long-term perspective. Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (Sheila Miyoshi Jager, W.W. Norton and Co., New York, 2013, 605 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover) takes the long history of conflict on the Korean Peninsula and melds it into a coherent narrative.

At least technically, the Korean War has never ended. This is brought home occasionally by North Korean saber rattling and the periodic exchanges of fire that still occur between the two Koreas. Yet, since the end of the actual Korean War in 1953, there has been little written in the intervening 60 years to bring the unhappy history of the two Koreas into a long-term perspective. Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea (Sheila Miyoshi Jager, W.W. Norton and Co., New York, 2013, 605 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover) takes the long history of conflict on the Korean Peninsula and melds it into a coherent narrative.

This narrative not only explains the historical events of the war in detail, but also examines the effect the ongoing war has had on the Cold War and the international arena since then. The book begins where the division of Korea began, at the end of World War II. The peninsula was quickly split into two countries and within a few years became a battlefield for the greater conflict of communism versus democracy.

The first half of the book deals with the Korean War, including a summary of the massive international effort in the West to stem the North Korean tide, which seemed unstoppable in the early days on the fighting. The successful United Nations counterattack drove North Korea to brink of defeat only to get a reprieve in the form of massive Chinese assistance. This brought the war to an effective stalemate.

After the cease-fire was signed, China declared a great victory in containing the United Nations forces, but the war was essentially unresolved for the Koreans. Decades of conflict followed, at times limited to rhetoric but occasionally reverting to shooting. Along the demilitarized zone, incidents were common, and constant political maneuvering was required by the United States, China, and the Soviet Union to maintain a balance of power acceptable to each. Intermittent crises such as the seizure of the USS Pueblo were seen as distractions from other pressing issues such as the Vietnam War. Despite the great powers’ ostensible support for North or South Korea, all of them valued maintaining a status quo that prevented war rather than allowing a final resolution of the Korean issue through renewed fighting.

The rise of the United States to its present position of world leadership is well documented but usually in separate works which concentrate on a specific era or conflict. Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies that brought America from Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (Conrad Black, Encounter Books, New York, 2013, 699 pp., maps, $35.99, hardcover) brings together the actions and plans which propelled America to the position it today enjoys.

The rise of the United States to its present position of world leadership is well documented but usually in separate works which concentrate on a specific era or conflict. Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies that brought America from Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (Conrad Black, Encounter Books, New York, 2013, 699 pp., maps, $35.99, hardcover) brings together the actions and plans which propelled America to the position it today enjoys.

The story begins with the Colonial Era, where a sense of national identity was forged and independence was won. A second section deals with how America faced the internal demon of slavery and secured itself on the continent and in the Western Hemisphere. This accomplished, the United States took its first steps onto the world stage, eventually becoming the “indispensable country” during World War II. Emerging from that conflict preeminent, the work concludes with America’s actions during the Cold War and beyond. The political, diplomatic, and social developments of each era are blended with the military activities that made the United States a world power, and eventually the world power.

Short Bursts

The New Zealand Wars 1820-72 (Ian Knight, Osprey Publishing, Botley, Oxford, UK, 2013, 48 pp., softcover) Part of the Men-at-Arms series, this book covers the various conflicts between the Maori tribes indigenous to New Zealand and the colonists, who arrived to settle there. Uniforms, weapons, and the organization of each side are explained in detail.

The New Zealand Wars 1820-72 (Ian Knight, Osprey Publishing, Botley, Oxford, UK, 2013, 48 pp., softcover) Part of the Men-at-Arms series, this book covers the various conflicts between the Maori tribes indigenous to New Zealand and the colonists, who arrived to settle there. Uniforms, weapons, and the organization of each side are explained in detail.

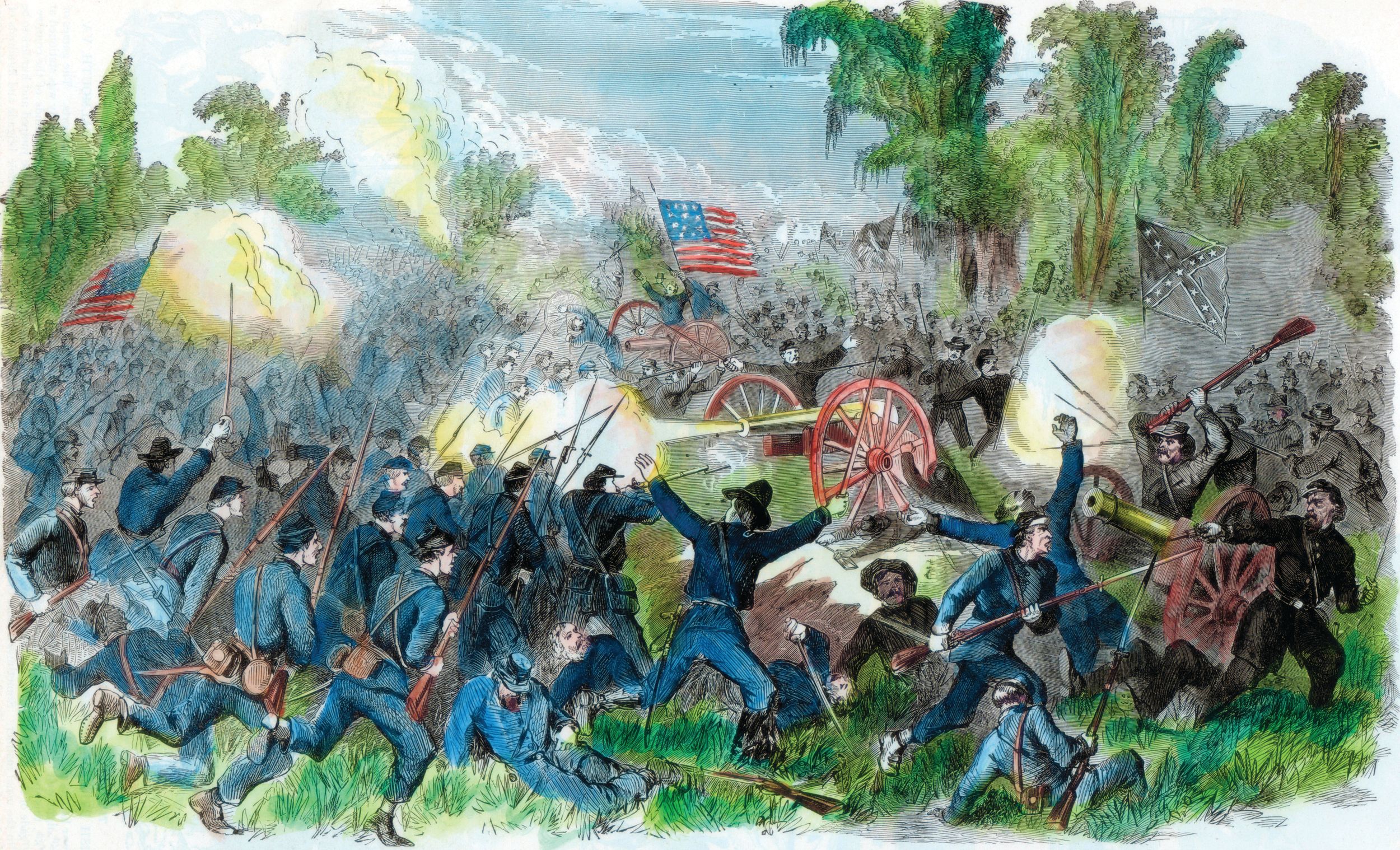

Mosby’s Raids in Civil War Northern Virginia (William S. Connery, The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2013, 158 pp., softcover) Known as the “Gray Ghost,” Colonel John Singleton Mosby conducted a partisan war in Northern Virginia, which gained him fame in the South and infamy in the North. This work is part of a series of books published for the 150-year anniversary of the Civil War.

Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War (Robert Gellately, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2013, 477 pp., photographs, notes, index, $32.50, hardcover) Using newly released Russian documents, this work covers the efforts of Josef Stalin to expand the grip of Communism across the globe.

Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, a Biography (Robert Wilson, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013, 261 pp., illustrations, notes, $28.00, hardcover) This biography of 19th-century America’s most important photographer. His studio sent camera teams to Civil War battlefields and provided the iconic images of the conflict.

Marching to the Drums: A History of Military Drums and Drummers (John Norris, Spellmount, Gloucestershire, UK, 2012, 159 pp., illustrations, notes, $22.95, softcover) Before their ceremonial role today, drums were an important signaling tool to maneuver and control armies in the field. The history leading to today’s tradition of military drums is covered in chronological fashion.

Marching to the Drums: A History of Military Drums and Drummers (John Norris, Spellmount, Gloucestershire, UK, 2012, 159 pp., illustrations, notes, $22.95, softcover) Before their ceremonial role today, drums were an important signaling tool to maneuver and control armies in the field. The history leading to today’s tradition of military drums is covered in chronological fashion.

Frontier Cavalry Trooper: The Letters of Private Eddie Matthews 1869-1874 (Douglas C. McChristian, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2013, 414 pp., illustrations, index, $55.00, hardcover) Private Matthews wrote extensive and detailed letters detailing his service in Arizona and New Mexico. They provide a chronicle of the daily life of frontier soldiers during America’s westward expansion.

Bringing It All Back Home: An Oral History of New York City’s Vietnam Veterans (Philip F. Napoli, Hill and Wang, New York, 2013, 254 pp., notes, $27.00, hardcover) The author spent years collecting the oral histories of New York veterans. This work collects the experiences of the Vietnam generation’s veterans.

Soviet and Russian Military Aircraft in the Middle East: Air Arms, Equipment and Conflicts Since 1955 (Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Komissarov, Crecy Publishing, Manchester, UK, 2013, 272 pp., $56.95, hardcover) This reference work highlights the service Soviet and Russian aircraft have seen in the Middle East’s wars from the Suez Crisis to the recent civil war in Syria. From the mid-1950s the Soviet Union widely distributed combat aircraft across the region.

Blood of Tyrants: George Washington and the Forging of the Presidency (Logan Bierne, Encounter Books, New York, 2013, 420 pp., $27.99, hardcover) This is a treatise on how Washington and the Continental Congress dealt with policy decisions during the American Revolution. The use of torture, treatment of spies, and other issues are covered using records and personal letters.

The Illustrated Gettysburg Reader (Rod Gragg, Regnery History, Washington D.C., 2013, 485 pp., $29.95, hardcover) Blow-by-blow coverage of the famous battle using the words of its participants and witnesses is provided. Each chapter examines a part of the battle through the writings of the officers and men who were there.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments